-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

L Ighina, A Caccianiga, A Moretti, S Belladitta, J W Broderick, G Drouart, J K Leung, N Seymour, New radio-loud QSOs at the end of the Re-ionization epoch, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 519, Issue 2, February 2023, Pages 2060–2068, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stac3668

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

We present the selection of high-redshift (z ≳ 5.7) radio-loud (RL) quasi-stellar object (QSO) candidates from the combination of the radio Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (RACS; at 888 MHz) and the optical/near-infrared Dark Energy Survey (DES). In particular, we selected six candidates brighter than |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}\gt 1$| mJy beam−1 and mag(zDES) < 21.3 using the dropout technique (in the i-band). From this sample, we were able to confirm the high-z nature (z ∼ 6.1) of two sources, which are now among the highest redshift RL QSOs currently known. Based on our Gemini-South/GMOS observations, neither object shows a prominent Ly α emission line. This suggests that both sources are likely to be weak emission-line QSOs hosting radio jets and would therefore further strengthen the potential increase of the fraction of weak emission-line QSOs recently found in the literature. However, further multiwavelength observations are needed to constrain the properties of these QSOs and of their relativistic jets. From the discovery of these two sources, we estimated the space density of RL QSOs in the redshift range 5.9 < z < 6.4 to be 0.13|$^{+0.18}_{-0.09}$| and found it to be consistent with the expectations based on our current knowledge of the blazar population up to z ∼ 5.

1 INTRODUCTION

The recent advent of wide-area optical and near-infrared (NIR) surveys, such as the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS; Chambers et al. 2016) and the Dark Energy Survey (DES; DES Collaboration 2018), has led to the discovery of several hundreds of z > 6 quasi-stellar objects (QSOs) (e.g. Morganson et al. 2012; Bañados et al. 2014, 2016; Jiang et al. 2016; Reed et al. 2017, 2019; Wang et al. 2019, 2021; Yang et al. 2020). The systematic study of these high-z systems in the optical and infrared (IR) has enabled the characterization of their supermassive black hole (SMBH; Mazzucchelli et al. 2017; Shen et al. 2019; Farina et al. 2022), their host galaxy (e.g. Venemans et al. 2020; Decarli et al. 2022) and their environment (e.g. Balmaverde et al. 2017; Ota et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2022). However, the properties of their relativistic jets are still poorly constrained. This is mainly due to the fact that the number of high-z QSOs detected in the radio band is still small (see e.g. Liu et al. 2021) and, as a consequence, the number of high-redshift radio-loud (RL, i.e. hosting powerful relativistic jets1) QSOs currently known is even smaller. Indeed, only ∼10 QSOs are currently known to be RL at z > 6. While five of them have been discovered in different wide-area radio surveys (J0309+2717 at z = 6.10, Belladitta et al. 2020, 2022b; J1427+3312 at z = 6.12, McGreer et al. 2006; J1429+5447 at z = 6.18, Willott et al. 2010; J2318−3113 at z = 6.44, Decarli et al. 2018; Ighina et al. 2021; J172.3556+18.7734 at z = 6.82, Bañados et al. 2021) the recent release of the LOFAR Two-metre Sky Survey (LoTSS, at 144 MHz; Shimwell et al. 2017, 2019, 2022), allowed the discovery of several new RL QSOs at z > 6 (between 3 and 5, depending on the assumed radio spectral indices; Gloudemans et al. 2021, 2022). Similarly, with the upcoming large-area radio surveys planned with the square kilometre array (SKA2; Braun et al. 2019) and its precursors, which will reach sensitivities of tens of μJy at ∼1 GHz (e.g. Norris et al. 2011, 2021), many new RL active galactic nuclei (AGNs), both QSOs and radio galaxies, are expected to be found at z ≳ 6.5. For example, Endsley et al. (2022a, b) very recently discovered the most distant radio galaxy currently known (at z = 6.85) in a 1.5 deg2 region, which implies the existence of many more similar systems over the entire sky. These new surveys will allow us to build complete samples of RL AGNs, from which to derive conclusive statistical properties on the entire population, well beyond the current redshift limit (z ∼ 5.5, e.g. Caccianiga et al. 2019). Having a large sample of RL AGNs at high-z will allow for a series of important scientific results, such as constraining the cosmic evolution of SMBHs hosted in systems with powerful jets directly after their formation (e.g. Volonteri et al. 2011; Diana et al. 2022) and studying the intergalactic medium (IGM) during the epoch of re-ionization trough neutral hydrogen (HI) absorption at low radio frequencies (e.g. Carilli, Gnedin & Owen 2002; Vrbanec et al. 2020).

In this work we present a sample of six z ≳ 5.7 RL QSO candidates built from the the cross-match of the second data release of the DES in the optical/NIR and the first data release of the low-band Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (RACS; McConnell et al. 2020; Hale et al. 2021), the first large-area radio survey performed with the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP; Hotan et al. 2021). From this sample, we have already identified two new RL QSOs at z > 6, DES J032021.431−352104.11 (z = 6.13; DES J0320−35 hereafter) and DES J032214.541−184118.15 (z = 6.09; DES J0322−18 hereafter).

This work is structured as follows: in Section 2 we outline the optical/NIR and radio criteria adopted for the selection of high-z RL QSO candidates; in Section 3 we present the spectroscopic confirmation of the two most promising candidates and their archival optical/NIR and radio data; in Section 4 we discuss the number of RL QSOs expected to be found at high redshift with future surveys; in Section 5 we summarize the conclusions of the work.

Throughout the paper we assume a flat ΛCDM cosmology with H0 = 70 km s−1 Mpc−1, Ωm = 0.3, and ΩΛ = 0.7. Spectral indices are given assuming Sν ∝ ν−α and all errors are reported at a 68 per cent confidence level, unless otherwise specified.

2 SELECTION CRITERIA

In order to efficiently select high-z RL QSOs, we started from the combination of the second data release of the DES and the first data release of the low-band RACS (simply RACS hereafter) survey and adopted the Lyman-break dropout technique (see e.g. Bañados et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2017, 2019; Belladitta et al. 2019, 2020, 2022a).

2.1 Optical and near/mid-infrared criteria

DES covers ∼5000 deg2 mostly in the southern extragalactic sky and it is one of the deepest wide-area optical/NIR surveys currently available. The limiting magnitudes at a signal-to-noise (S/N) level of 10 in its second data release are: gDES = 24.7, rDES = 24.4, iDES = 23.8, zDES = 23.1, and YDES = 21.7 mag (DES Collaboration 2021). In order to select bona-fide high-z QSO candidates, we accessed the products of DES through the dedicated SQL portal.3 To be as complete as possible, we set our criteria to recover almost all the 5.7 < z < 6.4 QSOs (both radio-loud and radio-quiet) with a magnitude in the zDES-band <21.3 already discovered in the DES area (28 in total), even if they were originally selected from another survey (i.e. with different filter sets). We adopted the following criteria for the candidate selection:

mag_auto_z <21.3,

class_star_z >0.85,

magerr_auto_z <0.3 and magerr_auto_y <0.3,

mag_auto_i − mag_auto_z >1,

non-detection in the g −band,4

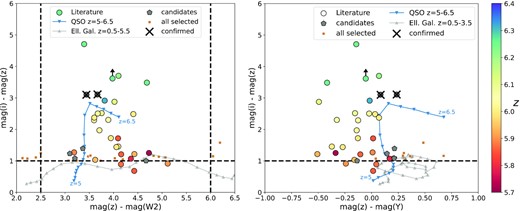

where all the magnitudes are in the AB system. These criteria are meant to select primarily compact stellar-like objects with a very faint emission in the g-band and an i − z dropout due to the Ly α absorption at high redshift and not to an artefact in the images. The total number of sources selected with these optical/NIR criteria (without the inspection of the g-band images) and with a radio association (see next subsection) is 25. After filtering the DES catalogue with the criteria reported above, we also considered mid-IR data from the catalogue Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (catWISE; Eisenhardt et al. 2020). In particular, by using a cross-match radius of 2 arcsec, we only kept candidates with |$2.5 \lt \tt {mag\_auto\_z} - \tt {mag\_W2} \lt 6$| (where the WISE magnitude is in the Vega system). This criterion should help us avoid absorbed QSOs and a subset of elliptical galaxies at low redshift (e.g. Carnall et al. 2015). In Fig. 1 we show the i − z versus z − W2 (left-hand panel) and the i − z versus z − Y (right-hand panel) colours for the z > 5.7 QSOs currently known in the DES area as well as for the selected candidates. Based on the colour cuts applied above, we recovered all but one of the already known QSOs at z > 5.9 (1 out of 20 sources not included, due to the class_star_z criterion). Whereas, three 5.7 < z < 5.9 QSOs were missed due to their small i − z colour value (3 out of 8, see Fig. 1). This is because at these redshifts, the Ly α emission line (∼8150–8400 Å in the observed frame) and its dropout shift to wavelengths covered by the i-band filter (∼7100–8500 Å). A systematic selection focused on the specific 5 < z < 5.9 redshift range will be presented in a future work.

mag(i) – mag(z) as a function of the mag(z) – mag(W2) (AB and Vega system, respectively; left-hand panel) and as a function of the mag(z) – mag(Y) one (right-hand panel) for the z > 5.7 QSOs currently known in the DES area (colour scale based on their redshift) together with the candidates selected with the criteria described in the text (grey pentagons). The brown squares indicate all the sources selected from the DES catalogue (i.e. not including the catWISE data and before the inspection of the g-band images). The blue line represents the expected colours of a typical QSO between redshift 5−6.5 and with a weak Ly α emission line (given by the combination of the composite spectrum derived in Bañados et al. 2016, see right-hand panel of Fig. 3 for example, and the QSO template described in Polletta et al. 2007). Similarly, the grey line represents the expected colours for a low-redshift (z = 0−3.5) elliptical galaxy (based on the template of Polletta et al. 2007). The limits used for the selection of bona-fide high-z candidates are shown with the horizontal and vertical black dashed lines.

2.2 Radio association

In order to only select radio-bright candidates, we cross-matched the optically selected sources with the first data release of RACS. This survey covers the entire sky south of +41° in declination with a median RMS of ∼0.25 mJy beam−1 and is also expected to perform more scans of the same area in the future also at higher frequencies (RACS-mid at ∼1.36 GHz and RACS-high at ∼1.65 GHz). We restricted our selection only to objects with a peak flux density Speak>1 mJy beam−1 and with a Sint/Speak<1.5 in order to select unresolved sources only, and therefore, reducing the position uncertainty of the radio counterpart. This last criterion is satisfied by all the 13 z > 5 RL QSOs already known in RACS area. Given the typical positional errors of RACS (about 2–3 arcsec, see section 3.4.3 in McConnell et al. 2020), we adopted a search radius of 3 arcsec between the optical and the radio counterparts. We note that for this first search, we made use of the source lists derived from the images described in McConnell et al. (2020)5 since the final catalogue of RACS-low survey built by Hale et al. (2021), where all the images have been combined together after being convolved to a common resolution of 25 arcsec, would further increase the position uncertainty, especially for faint sources. Nevertheless, in the following, to ensure a reliable flux density measurement when presenting a radio flux density of a source from RACS, we will consider the values reported in the Hale et al. (2021) catalogue.

We also cross-matched the optically selected candidates with the catalogue derived from the ‘convolved’ images of the pilot evolutionary map of the Universe (EMU) survey (Norris et al. 2021), which is at a similar frequency (944 MHz), it has a similar angular resolution (∼18 arcsec), but it is significantly deeper (RMS ∼25–30 μJy beam−1 over ∼270 deg2). By adopting a radio-optical association of 1.5 arcsec (which is enough to account for both the accuracy and precision uncertainties of the sources in the catalogue, see Norris et al. 2021) and the same optical/NIR and radio criteria reported above, we select one more >1 mJy beam−1 candidate.

Finally, for sources at dec >−40° and bright enough to be detected in the VLA Sky Survey (VLASS; resolution ∼2.5 arcsec at 3 GHz; Lacy et al. 2020), we also checked their radio images in this survey and only kept the candidates if a >3 ×RMS signal is present within 1.2 arcsec from the optical/NIR counterpart. In this way we discarded 3 sources out of the 11 covered by VLASS.

The total number of candidates selected with the optical/IR and radio criteria described above is six and we report in Table 1 their main properties used for the selection. In the following we focus on two of them, which have already been confirmed spectroscopically, while the remaining candidates will be part of a future publication.

Col. (1, 2, 3): name and optical coordinates of the source. The check-mark beside the name indicate the sources that have already been confirmed; Col. (4): peak flux densities (with the corresponding error) at 888 MHz from the RACS catalogue derived by Hale et al. (2021) (* indicates flux densities at 944 MHz from EMU, whose uncertainty corresponds to the RMS of the image); Col. (5): z-band magnitude from DES with the corresponding error; Col. (6): dropout value (i − z); Col. (7): zDES − W2 colour, where zDES is in the AB system and W2 in the Vega system; Col. (8): radio-to-optical distance; Col. (9): radio survey from which the candidate was selected.

| NAME . | RA . | Dec . | |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}$| . | zDES . | (i − z)DES . | zDES − W2 . | Distancero . | Radio survey . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | (mJy beam−1) . | (mag AB) . | . | (mag AB – Vega) . | (arcsec) . | . |

| DES J0249−28 | 42.311270 | −28.855045 | 5.06 ± 0.27 | 20.83 ± 0.03 | 1.23 | 3.09 | 2.01 | RACS |

| DES J0320−35 |$\checkmark$| | 50.089335 | −35.351148 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 3.11 | 3.28 | 1.32 | RACS |

| DES J0322−18 |$\checkmark$| | 50.560622 | −18.688189 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 20.94 ± 0.04 | 3.11 | 3.44 | 2.59 | RACS |

| DES J0427−53 | 66.930894 | −53.39384 | 3.61 ± 0.33 | 20.04 ± 0.01 | 1.08 | 3.20 | 1.47 | RACS |

| DES J0616−48 | 94.199469 | −48.347094 | 2.13 ± 0.42 | 21.24 ± 0.03 | 1.39 | 3.37 | 2.76 | RACS |

| DES J2020−62 | 305.170194 | −62.252554 | 1.09 ± 0.06* | 19.23 ± 0.01 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 0.80 | EMU |

| NAME . | RA . | Dec . | |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}$| . | zDES . | (i − z)DES . | zDES − W2 . | Distancero . | Radio survey . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | (mJy beam−1) . | (mag AB) . | . | (mag AB – Vega) . | (arcsec) . | . |

| DES J0249−28 | 42.311270 | −28.855045 | 5.06 ± 0.27 | 20.83 ± 0.03 | 1.23 | 3.09 | 2.01 | RACS |

| DES J0320−35 |$\checkmark$| | 50.089335 | −35.351148 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 3.11 | 3.28 | 1.32 | RACS |

| DES J0322−18 |$\checkmark$| | 50.560622 | −18.688189 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 20.94 ± 0.04 | 3.11 | 3.44 | 2.59 | RACS |

| DES J0427−53 | 66.930894 | −53.39384 | 3.61 ± 0.33 | 20.04 ± 0.01 | 1.08 | 3.20 | 1.47 | RACS |

| DES J0616−48 | 94.199469 | −48.347094 | 2.13 ± 0.42 | 21.24 ± 0.03 | 1.39 | 3.37 | 2.76 | RACS |

| DES J2020−62 | 305.170194 | −62.252554 | 1.09 ± 0.06* | 19.23 ± 0.01 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 0.80 | EMU |

Col. (1, 2, 3): name and optical coordinates of the source. The check-mark beside the name indicate the sources that have already been confirmed; Col. (4): peak flux densities (with the corresponding error) at 888 MHz from the RACS catalogue derived by Hale et al. (2021) (* indicates flux densities at 944 MHz from EMU, whose uncertainty corresponds to the RMS of the image); Col. (5): z-band magnitude from DES with the corresponding error; Col. (6): dropout value (i − z); Col. (7): zDES − W2 colour, where zDES is in the AB system and W2 in the Vega system; Col. (8): radio-to-optical distance; Col. (9): radio survey from which the candidate was selected.

| NAME . | RA . | Dec . | |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}$| . | zDES . | (i − z)DES . | zDES − W2 . | Distancero . | Radio survey . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | (mJy beam−1) . | (mag AB) . | . | (mag AB – Vega) . | (arcsec) . | . |

| DES J0249−28 | 42.311270 | −28.855045 | 5.06 ± 0.27 | 20.83 ± 0.03 | 1.23 | 3.09 | 2.01 | RACS |

| DES J0320−35 |$\checkmark$| | 50.089335 | −35.351148 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 3.11 | 3.28 | 1.32 | RACS |

| DES J0322−18 |$\checkmark$| | 50.560622 | −18.688189 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 20.94 ± 0.04 | 3.11 | 3.44 | 2.59 | RACS |

| DES J0427−53 | 66.930894 | −53.39384 | 3.61 ± 0.33 | 20.04 ± 0.01 | 1.08 | 3.20 | 1.47 | RACS |

| DES J0616−48 | 94.199469 | −48.347094 | 2.13 ± 0.42 | 21.24 ± 0.03 | 1.39 | 3.37 | 2.76 | RACS |

| DES J2020−62 | 305.170194 | −62.252554 | 1.09 ± 0.06* | 19.23 ± 0.01 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 0.80 | EMU |

| NAME . | RA . | Dec . | |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}$| . | zDES . | (i − z)DES . | zDES − W2 . | Distancero . | Radio survey . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (deg) . | (deg) . | (mJy beam−1) . | (mag AB) . | . | (mag AB – Vega) . | (arcsec) . | . |

| DES J0249−28 | 42.311270 | −28.855045 | 5.06 ± 0.27 | 20.83 ± 0.03 | 1.23 | 3.09 | 2.01 | RACS |

| DES J0320−35 |$\checkmark$| | 50.089335 | −35.351148 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 3.11 | 3.28 | 1.32 | RACS |

| DES J0322−18 |$\checkmark$| | 50.560622 | −18.688189 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 20.94 ± 0.04 | 3.11 | 3.44 | 2.59 | RACS |

| DES J0427−53 | 66.930894 | −53.39384 | 3.61 ± 0.33 | 20.04 ± 0.01 | 1.08 | 3.20 | 1.47 | RACS |

| DES J0616−48 | 94.199469 | −48.347094 | 2.13 ± 0.42 | 21.24 ± 0.03 | 1.39 | 3.37 | 2.76 | RACS |

| DES J2020−62 | 305.170194 | −62.252554 | 1.09 ± 0.06* | 19.23 ± 0.01 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 0.80 | EMU |

2.3 Completeness and contamination

With the optical/IR thresholds reported above, we recover about 95 per cent of the already discovered z > 5.9 QSOs, while the remaining 5 per cent (one object) does not satisfy the point-like criterion. We note that this value does not take into account the actual completeness of the literature sources in the DES field. Several works showed that the high-z QSO selections based on colour cuts (such as ours) can be considered almost complete for relatively bright high-z QSOs (magnitudes <22), see, for example, fig. 3 in Willott et al. (2010) and fig. 10 in Kim et al. (2022). Thanks to the radio counterpart requirement, our selection criteria are less strict compared to the usual cuts adopted in other works based on the optical/IR colours only, both in terms of the dropout value and in the colours of the continuum (i.e. the z − Y colour; see e.g. Venemans et al. 2013; Bañados et al. 2016; Reed et al. 2017, 2019). Therefore, in the following, we adopt the 95 per cent value as the best estimate of the completeness of our selection, noting that only significantly different values (completeness <40 per cent) would change our results in Section 4, given the limited statistics.

In order to estimate the completeness related to the radio criteria adopted for RACS, we considered the ASKAP observations of the 23rd GAlaxy Mass Assembly (G23; Driver et al. 2011) field described in Gürkan et al. (2022). This field covers 83 deg2 in the southern hemisphere (centred at RA = 23h and Dec = −32°) and was observed in the radio band with the ASKAP telescope as part of the EMU Early Science programme. These observations are similar to RACS both in terms of central frequency and resolution (888 MHz and ∼10 arcsec, respectively), but they are about an order of magnitude deeper (RMS∼38 μJy beam−1). From the catalogue derived by Gürkan et al. (2022), we considered all the sources with Sint/Speak < 1.5, to ensure the selection of point-like objects only, and with 1 < Speak < 30 mJy beam−1, that is, with radio flux densities similar to our selected high-z QSO candidates, and evaluated the fraction of these objects detected in RACS. In the top panel of Fig. 2 we report the flux density distribution of all the point-like 1 < Speak < 30 mJy beam−1 G23 objects (empty histogram) and the subset detected in the RACS catalogue (filled histogram). In the lower panels we report the fraction of sources detected in RACS per bin of flux density (central panel) and their cumulative completeness fraction above a given flux density (bottom panel). Based on the detection fraction in RACS, we expect our overall radio selection to be about 75 per cent complete for S|$_\mathrm{888\, MHz}\gt 1$| mJy beam−1. In particular, while for relatively large radio flux densities (S|$_\mathrm{888\, MHz}\gt 3$| mJy beam−1) the detection fraction is almost one (∼94 per cent) the detection fraction drops to about 65 per cent for faint radio sources (1 < S|$_\mathrm{888\, MHz}\lt 3$| mJy beam−1). These values are similar to the ones derived by Hale et al. (2021) for the RACS catalogue after combining the different images to a common resolution (see their fig. 15, left-hand panel).

Fraction of point-like radio sources present in the G23 field with 1 < S|$_\mathrm{888\, MHz}\lt 30$| mJy beam−1 detected in RACS. Top: flux density distribution of all the 1 < S|$_\mathrm{888\, MHz}\lt 30$| mJy beam−1 point-like sources present in the G23 field (empty histogram), together with the distribution of the ones detected in RACS (filled histogram); Centre: detection fraction in RACS per flux density bin; Bottom: cumulative fraction of sources detected in RACS as a function of flux density.

Based on these values, and the total number of candidates selected from RACS (see Table 1), in our selection we expect to be missing about two candidates (∼2.04). Moreover, if we consider the overall area of the DES (∼5000 deg2), we would expect to find ∼0.4 sources in the region covered by the EMU pilot survey (∼270 deg2), which is consistent with the selection of one candidate in this area.

Finally, in order to determine the number of spurious associations we can expect from our selection, we cross-matched the DES catalogue with the RACS and EMU ones by applying a rigid relative shift in their positions and then applied the same selection criteria used for the selection of our candidates. In this way, we found that the expected number of spurious associations is 1.6 ± 0.5.

3 DISCOVERY OF TWO NEW z > 6 RL QSOs

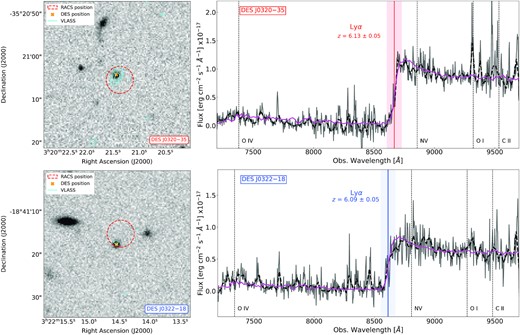

While the spectroscopic observations of the majority of the sample are currently ongoing, we confirmed the high-z nature of two candidates: DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18. These two sources were selected as the first targets to be observed because they had the highest dropout in our sample (i − z > 3, see Fig. 1) as well as a further radio association (<0.5 arcsec with S/N >3) in the quick-look images of VLASS at 3 GHz. In the left-hand panels of Fig. 3, we report the optical (DES, orange cross) and radio positions (RACS, dashed red circle corresponding to the radio positional uncertainty of each source) as well as the VLASS contours overlaid on the optical images in the zDES filter of both QSOs.

Left-hand panel: 30 arcsec ×30 arcsec cutout around DES J0320−35 (top) and DES J0322−18 (bottom) in the zDES filter. The optical and radio positions are shown with an orange cross and a dashed red circle (uncertainty reported in the RACS catalogue), respectively, while the VLASS radio (3 GHz) contours at 3,4,5 × RMS are displayed in cyan. Right-hand panel: Optical/NIR spectra of DES J0320−35 (at z = 6.13 ± 0.05; top) and DES J0318−18 (at z = 6.09 ± 0.05; bottom) obtained with the GMOS instrument on the Gemini-South telescope at 3Å resolution. The dashed black lines are the spectra smoothed to a 20 Å resolution. The red and blue vertical lines indicate the expected wavelength of the Ly α emission line. The solid magenta line is the composite spectrum derived by Bañados et al. (2016) for 5.6 < z < 6.5 QSOs with a weak Ly α emission line (like our sources), also smoothed to a 20 Å resolution.

3.1 Spectroscopic confirmation and optical/NIR properties

We confirmed both candidates to be high-z QSOs with the Gemini-South telescope, DES J0320−35 on 2021 August 9 and DES J0322−18 on 2021 October 14–15 (program ID: GS-2021A-DD-112; P.I. L. Ighina). The observations were carried out with the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph (GMOS; Hook et al. 2004) instrument in long-slit mode (1 arcsec aperture) and with the R400 grating. The mean airmass during the observations was 1.03 and 1.33, while the seeing was ∼0.9 and ∼0.7 arcsec for DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18, respectively. Both targets were observed for a total of eight exposures, half with the central wavelength of the grism at 9000 Å and half at 9100 Å, in order to cover the spectral gap in the detector. For DES J0320−35, each segment lasted 450 s (3600 s in total), while for DES J0322−18, each segment lasted 800 s (6400 s in total). We also observed the spectrophotometric standard star LP 995−86 in order to correct the spectra of the two targets for the response of the instrument.

The data were then reduced using the dedicated iraf Gemini package and following the instructions reported in the GMOS Data Reduction Cookbook (Version 1.1; Tucson, AZ: National Optical Astronomy Observatory; Shaw, R. A. 2016).6The RMS reached during the wavelength calibrations was ∼0.18 Å for both observations. Finally, since the nights of the observations were not in photometric conditions, in order to have an absolute flux calibration, the two spectra were normalized to the z and Y photometric data available from different surveys, by considering the magnitudes corrected by the Galaxy absorption as reported in the corresponding catalogue.

In both cases, the presence of a high drop in the continuum spectrum at about ∼8700 Å confirms the high-z nature of the candidates. However, due to the lack of evident spectral lines in the observed range, we used the observed wavelength of the drop to estimate the best-fitting redshift for both sources. In particular, we considered the composite spectrum derived by Bañados et al. (2016) from a sample of 16 QSOs at 5.6 < z < 6.5 with a weak Ly α emission line (rest-frame equivalent width, REW, <15.4 Å) and, after smoothing it to a 20 Å resolution, we used it to perform a fit to the observed spectrum, also smoothed to 20 Å, in the wavelength range 8000–9500 Å, where the only free parameters were the redshift and the normalization. The best-fitting redshift values we obtained are the following: z = 6.13 ± 0.05 for DES J0320−35 and z = 6.09 ± 0.05 for DES J0320−18. As error on these estimates we consider 3 × 20 Å (σz = ±0.05), which roughly corresponds to the width of the observed drops. Nevertheless, further observations with a larger wavelength range are needed to accurately determine their redshift.

The reduced spectra together with the high-z QSOs composite spectra are reported in the right-hand panels of Fig. 3. In Table 2 we list the magnitudes of both QSOs (AB system7) in the optical and the IR available from the following surveys: DES, Pan-STARRS, the VISTA Kilo-degree Infrared Galaxy Public Survey (VIKING; Edge et al. 2013), the VISTA Hemisphere Survey (VHS; McMahon et al. 2013), and the catWISE. In order to compute the optical spectral index of the two sources, we considered the power law that best describes the continuum obtained from all the NIR photometric data points, that is, the filters Y, J, H, Ks, also from different surveys when available. The resulting spectral indices are as follows: |$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^{\mathrm{\lambda }}=1.72\pm 0.03$| (|$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^{\mathrm{\nu }}=0.28$|; DES J0320−35) and |$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^{\mathrm{\lambda }}=1.60\pm 0.04$| (|$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^{\mathrm{\nu }}=0.40$|; DES J0322−18), which are roughly consistent with the typical values found in QSOs (e.g. Vanden Berk et al. 2001).

Optical and IR magnitudes (AB system) of DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18 available from the DES, VIKING, VHS, and catWISE surveys. For DES J0322−18 we report the magnitudes from PanSTARRS in brackets. Upper limits are given at a 5σ significance level. We also report the slope of the continuum and the rest-frame luminosities at 2500 and 4400 Å.

| Filter . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . |

|---|---|---|

| rDES (rPS) | >24.56 | >24.56 (>23.20) |

| iDES (iPS) | 23.70 ± 0.24 | >23.96 (>23.10) |

| zDES (zPS) | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 20.94 ± 0.04 (21.77 ± 0.07) |

| YDES (YPS) | 20.36 ± 0.08 | 20.86 ± 0.11 (20.77 ± 0.12) |

| zVista | 20.88 ± 0.05 | – |

| YVista | 20.33 ± 0.07 | – |

| JVista | 20.24 ± 0.08 | 20.55 ± 0.12 |

| HVista | 20.20 ± 0.11 | – |

| KVista | 20.11 ± 0.17 | 20.68 ± 0.39 |

| W1 | 20.01 ± 0.06 | 20.28 ± 0.08 |

| W2 | 20.27 ± 0.12 | 20.84 ± 0.23 |

| |$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^\mathrm{\lambda }$| | 1.72 ± 0.03 | 1.60 ± 0.04 |

| L2500Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 1.80|$^{+0.21}_{-0.19} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.20|$^{+0.19}_{-0.16} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

| L4400Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 2.11|$^{+0.24}_{-0.22} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.52|$^{+0.24}_{-0.21} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

| Filter . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . |

|---|---|---|

| rDES (rPS) | >24.56 | >24.56 (>23.20) |

| iDES (iPS) | 23.70 ± 0.24 | >23.96 (>23.10) |

| zDES (zPS) | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 20.94 ± 0.04 (21.77 ± 0.07) |

| YDES (YPS) | 20.36 ± 0.08 | 20.86 ± 0.11 (20.77 ± 0.12) |

| zVista | 20.88 ± 0.05 | – |

| YVista | 20.33 ± 0.07 | – |

| JVista | 20.24 ± 0.08 | 20.55 ± 0.12 |

| HVista | 20.20 ± 0.11 | – |

| KVista | 20.11 ± 0.17 | 20.68 ± 0.39 |

| W1 | 20.01 ± 0.06 | 20.28 ± 0.08 |

| W2 | 20.27 ± 0.12 | 20.84 ± 0.23 |

| |$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^\mathrm{\lambda }$| | 1.72 ± 0.03 | 1.60 ± 0.04 |

| L2500Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 1.80|$^{+0.21}_{-0.19} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.20|$^{+0.19}_{-0.16} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

| L4400Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 2.11|$^{+0.24}_{-0.22} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.52|$^{+0.24}_{-0.21} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

Optical and IR magnitudes (AB system) of DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18 available from the DES, VIKING, VHS, and catWISE surveys. For DES J0322−18 we report the magnitudes from PanSTARRS in brackets. Upper limits are given at a 5σ significance level. We also report the slope of the continuum and the rest-frame luminosities at 2500 and 4400 Å.

| Filter . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . |

|---|---|---|

| rDES (rPS) | >24.56 | >24.56 (>23.20) |

| iDES (iPS) | 23.70 ± 0.24 | >23.96 (>23.10) |

| zDES (zPS) | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 20.94 ± 0.04 (21.77 ± 0.07) |

| YDES (YPS) | 20.36 ± 0.08 | 20.86 ± 0.11 (20.77 ± 0.12) |

| zVista | 20.88 ± 0.05 | – |

| YVista | 20.33 ± 0.07 | – |

| JVista | 20.24 ± 0.08 | 20.55 ± 0.12 |

| HVista | 20.20 ± 0.11 | – |

| KVista | 20.11 ± 0.17 | 20.68 ± 0.39 |

| W1 | 20.01 ± 0.06 | 20.28 ± 0.08 |

| W2 | 20.27 ± 0.12 | 20.84 ± 0.23 |

| |$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^\mathrm{\lambda }$| | 1.72 ± 0.03 | 1.60 ± 0.04 |

| L2500Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 1.80|$^{+0.21}_{-0.19} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.20|$^{+0.19}_{-0.16} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

| L4400Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 2.11|$^{+0.24}_{-0.22} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.52|$^{+0.24}_{-0.21} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

| Filter . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . |

|---|---|---|

| rDES (rPS) | >24.56 | >24.56 (>23.20) |

| iDES (iPS) | 23.70 ± 0.24 | >23.96 (>23.10) |

| zDES (zPS) | 20.59 ± 0.03 | 20.94 ± 0.04 (21.77 ± 0.07) |

| YDES (YPS) | 20.36 ± 0.08 | 20.86 ± 0.11 (20.77 ± 0.12) |

| zVista | 20.88 ± 0.05 | – |

| YVista | 20.33 ± 0.07 | – |

| JVista | 20.24 ± 0.08 | 20.55 ± 0.12 |

| HVista | 20.20 ± 0.11 | – |

| KVista | 20.11 ± 0.17 | 20.68 ± 0.39 |

| W1 | 20.01 ± 0.06 | 20.28 ± 0.08 |

| W2 | 20.27 ± 0.12 | 20.84 ± 0.23 |

| |$\alpha _\mathrm{o}^\mathrm{\lambda }$| | 1.72 ± 0.03 | 1.60 ± 0.04 |

| L2500Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 1.80|$^{+0.21}_{-0.19} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.20|$^{+0.19}_{-0.16} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

| L4400Å (erg s−1 Hz−1) | 2.11|$^{+0.24}_{-0.22} \, \times 10^{31}$| | 1.52|$^{+0.24}_{-0.21} \, \times 10^{31}$| |

3.2 Archival radio data

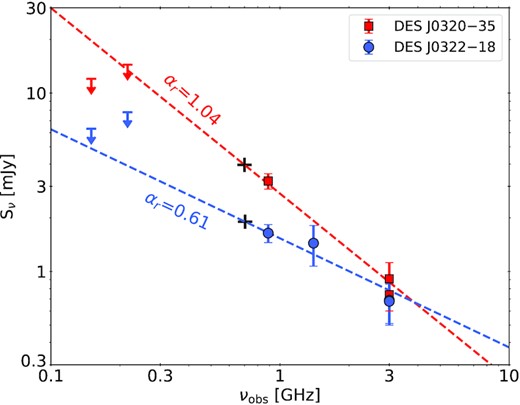

To characterize the radio properties of these two newly discovered QSOs, we searched for archival data from past and current radio surveys. As already mentioned, both QSOs were first selected from RACS, where they were detected with a high S/N (>11 for DES J0320−35, off-source RMS∼0.28 mJy beam−1, and >8 for DES J0322−18, off-source RMS∼0.19 mJy beam−1, according to the catalogue derived by Hale et al. 2021). Furthermore, their radio association was also confirmed by the VLASS quick-look images, which have an higher angular resolution (∼2.5 arcsec). As the VLASS quick-look images might be unreliable at low flux densities, we added a further 10 per cent to the uncertainty of their flux densities in this work (for details, see Gordon et al. 2021).

At the same time, we also checked the other publicly available radio surveys. At low frequency, we did not find a counterpart in the TIFR Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope Sky Survey (TGSS; Intema et al. 2017), at 148 MHz, nor in the GaLactic and Extragalactic All-sky Murchison Widefield Array South Galactic Pole (GLEAM-SGP; Franzen et al. 2021), at 216 MHz.8 The RMS values between our two sources differ significantly due to the presence of a very bright object near DES J0320−35. Moreover, DES J0322−18 is also detected in the NRAO VLA Sky Survey (NVSS; Condon et al. 1998) at 1.4 GHz with a 4σ significance (RMS∼0.37 mJy beam−1, at a distance <5 arcsec), even if not reported in the catalogue. Near DES J0320−35 a radio signal is also present, but the corresponding emission peak is 25 arcsec away. Since this distance is larger than the pixel size of the NVSS images (15 arcsec) we do not consider the corresponding flux density.

We summarize in Table 3 the flux density measurements of both sources in the radio surveys described above. For both QSOs we consider the peak flux density of each image since neither of them is resolved. In case of a non-detection, we report the upper limit computed as 3×local RMS. From both the detections and non-detections, the power law that best describe the two radio spectra have spectral indices of αr = 1.04 ± 0.07 (DES J0320−35) and αr = 0.61 ± 0.11 (DES J0322−18), obtained with the MRMOOSE code (Drouart & Falkendal 2018a, b). In Fig. 4 we show the radio detections and upper limits of both QSOs together with the best-fitting power law. These values are consistent with the ones typically observed in RL AGNs (e.g. Bañados et al. 2021), even though they are relatively uncertain given the few data available and the potential intrinsic variability. From the combination of the LoTSS (144 MHz) and the Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters (FIRST, 1.4 GHz; Becker, White & Helfand 1995) surveys, Gloudemans et al. (2021, 2022) found that z > 5 QSOs have a median spectral index of αr = 0.3. This difference can be attributed to two main factors: the frequency range probed by the different works and the unprecedented sensitivity reached by LoTSS. Indeed, while typical high-z RL QSOs have spectral indices of ∼0.7–1 (e.g. Bañados et al. 2015; Spingola et al. 2020), many of them also present a turnover in the radio spectrum at observed frequencies of 0.5–2 GHz (e.g. Belladitta et al. 2022a; Ighina et al. 2022b; Shao et al. 2022), which can be interpreted as a nearly flat spectrum from a two-point spectral index with a measurement at very low frequencies. Moreover, since the FIRST survey is shallower, compered to LoTSS, the sources with a measurement in both surveys are likely to have a nearly flat or even negative spectral index (see section 3 in Gloudemans et al. 2021).

Radio data available for DES J0320−35 (red squares) and DES J0322−18 (blue circles). The dashed lines represent the single power law that best fit the data of each source. The black crosses correspond to the extrapolated flux density at the 5 GHz rest-frame frequency of each object.

Radio data available from public surveys for DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18. Since the sources are not resolved, we report the peak flux density measured in each image. Upper limits are at a 3σ significance level. We also report the best-fitting spectral index, the luminosity density at 5 GHz rest frame and the radio-loudness parameter.

| . | . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Frequency | Sν | RMS | Sν | RMS |

| (MHz) | (mJy beam−1) | (mJy beam−1) | |||

| TGSS | 148 | <12.2 | 4.1 | <6.3 | 2.1 |

| GLEAM-SGP | 216 | <14.5 | 4.8 | <7.8 | 2.6 |

| RACS | 888 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 0.28 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 0.19 |

| NVSS | 1400 | – | 0.45 | 1.44 ± 0.37 | 0.37 |

| VLASS (1) | 3000 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.17 |

| VLASS (2) | 3000 | 0.91 ± 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.17 | 0.15 |

| αr | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.11 | |||

| L5GHz (W Hz−1) | 2.42|$^{+0.25}_{-0.25}\times 10^{26}$| | 1.10|$^{+0.16}_{-0.15} \, \times 10^{26}$| | |||

| R = S5GHz/S4400Å | 115 ± 18 | 73 ± 15 | |||

| . | . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Frequency | Sν | RMS | Sν | RMS |

| (MHz) | (mJy beam−1) | (mJy beam−1) | |||

| TGSS | 148 | <12.2 | 4.1 | <6.3 | 2.1 |

| GLEAM-SGP | 216 | <14.5 | 4.8 | <7.8 | 2.6 |

| RACS | 888 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 0.28 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 0.19 |

| NVSS | 1400 | – | 0.45 | 1.44 ± 0.37 | 0.37 |

| VLASS (1) | 3000 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.17 |

| VLASS (2) | 3000 | 0.91 ± 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.17 | 0.15 |

| αr | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.11 | |||

| L5GHz (W Hz−1) | 2.42|$^{+0.25}_{-0.25}\times 10^{26}$| | 1.10|$^{+0.16}_{-0.15} \, \times 10^{26}$| | |||

| R = S5GHz/S4400Å | 115 ± 18 | 73 ± 15 | |||

Radio data available from public surveys for DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18. Since the sources are not resolved, we report the peak flux density measured in each image. Upper limits are at a 3σ significance level. We also report the best-fitting spectral index, the luminosity density at 5 GHz rest frame and the radio-loudness parameter.

| . | . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Frequency | Sν | RMS | Sν | RMS |

| (MHz) | (mJy beam−1) | (mJy beam−1) | |||

| TGSS | 148 | <12.2 | 4.1 | <6.3 | 2.1 |

| GLEAM-SGP | 216 | <14.5 | 4.8 | <7.8 | 2.6 |

| RACS | 888 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 0.28 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 0.19 |

| NVSS | 1400 | – | 0.45 | 1.44 ± 0.37 | 0.37 |

| VLASS (1) | 3000 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.17 |

| VLASS (2) | 3000 | 0.91 ± 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.17 | 0.15 |

| αr | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.11 | |||

| L5GHz (W Hz−1) | 2.42|$^{+0.25}_{-0.25}\times 10^{26}$| | 1.10|$^{+0.16}_{-0.15} \, \times 10^{26}$| | |||

| R = S5GHz/S4400Å | 115 ± 18 | 73 ± 15 | |||

| . | . | DES J0320−35 . | DES J0322−18 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Frequency | Sν | RMS | Sν | RMS |

| (MHz) | (mJy beam−1) | (mJy beam−1) | |||

| TGSS | 148 | <12.2 | 4.1 | <6.3 | 2.1 |

| GLEAM-SGP | 216 | <14.5 | 4.8 | <7.8 | 2.6 |

| RACS | 888 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 0.28 | 1.64 ± 0.19 | 0.19 |

| NVSS | 1400 | – | 0.45 | 1.44 ± 0.37 | 0.37 |

| VLASS (1) | 3000 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.17 |

| VLASS (2) | 3000 | 0.91 ± 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.17 | 0.15 |

| αr | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.11 | |||

| L5GHz (W Hz−1) | 2.42|$^{+0.25}_{-0.25}\times 10^{26}$| | 1.10|$^{+0.16}_{-0.15} \, \times 10^{26}$| | |||

| R = S5GHz/S4400Å | 115 ± 18 | 73 ± 15 | |||

Interestingly, the non-detection in the TGSS survey at 148 MHz might imply a flattening of the radio spectrum or the presence of a turnover at lower frequencies also for DES J0320−35. While for DES J0322−18, given its relatively flat spectrum, the upper limits at low frequencies are still consistent with the single power-law extrapolation. In both cases more radio observations are needed to accurately constrain the spectrum and the nature of the two RL QSOs.

3.3 Lack of spectral emission lines

Based on the optical/NIR spectra obtained from Gemini-GMOS, neither source shows prominent emission lines in the observed range (namely Ly α). Given their RL nature, the lack of emission lines could be associated with a BL Lacertae (BL Lac) nature (REW <5 Å; e.g. Padovani 2017). If confirmed, these would be the farthest BL Lac objects currently known, with other three potential candidates at z > 6 (see Gloudemans et al. 2022; Koptelova & Hwang 2022). In this case, we would expect to observe a nearly flat radio spectrum; simultaneous observations in the radio band would be needed to reliably constrain the spectral slopes of these sources. Another possibility could be that these are weak emission-line QSOs (WLQSOs) that happen to host two powerful relativistic jets (similarly to the z = 6.18 RL QSO J1429+5447, Shen et al. 2019, and the ones discussed in Gloudemans et al. 2022). As their name suggests, these are QSOs with very weak emission lines (REW[CIV1549 Å] <15.4 Å; Diamond-Stanic et al. 2009). The physical conditions of these sources are not fully clear. The two main scenarios proposed to explain the lack of strong emission lines involve either a young accretion system (e.g. Eilers, Hennawi & Davies 2018; Andika et al. 2020, 2022), where the Broad Line Region (BLR) has not fully formed yet (e.g. Meusinger & Balafkan 2014), or a softer ionizing continuum, due to different accretion properties or absorption between the disc and the BLR (e.g. Luo et al. 2015).

Interestingly, recent works did find an increase of the WLQSO fraction at high redshift being ∼10–14 per cent at z ≳ 5.7 (e.g. Bañados et al. 2016; Shen et al. 2019), as opposed to ∼6 per cent found by Diamond-Stanic et al. (2009) considering 3 < z < 5 QSOs. For the RL population the observed evolution is even more pronounced, with ∼38 per cent RL QSOs at z > 5 being classified as WLQSOs (see e.g. Gloudemans et al. 2022). Therefore, this redshift evolution can indicate possible changes in the accretion mode of SMBHs and also in the RQ/RL populations. However, current estimates from z > 5 studies are still limited by small number statistics. If the weak-line nature of both objects was confirmed, it would further strengthen the presence of an increase of WLQSOs as a function of redshift. However the spectroscopic identification of the remaining candidates selected in this work is needed to have an estimate of the weak-line fraction in our sample. Moreover, we stress once again that an NIR spectrum covering a larger wavelength range and with a higher S/N is needed in order to understand conditions of the accretion and of the BLR in these two confirmed high-z QSOs.

4 COMPARISON WITH EXPECTATIONS

Thanks to its wide area coverage and relatively deep radio/optical sensitivity, the combination of RACS+DES is currently one of the most effective tools for selecting high-z RL QSOs. From our work, we can derive an estimate of the space density of RL QSOs with |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}\gt 1$| mJy beam−1 and mag(zDES) < 21.3 at 5.9 < z < 6.4, where our selection is nearly complete (∼71 per cent, considering both the optical/NIR and radio completeness, see Section 2). Based on the discovery of DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18 over an area of 5000 deg2 (corresponding to a comoving volume slice of 21.5 Gpc3 between 5.9 < z < 6.4) the resulting space density is 0.13|$^{+0.18}_{- 0.09}$| Gpc−3. As uncertainties we considered the Poissonian error (lower) and the total number of candidates selected from RACS (5; upper). However, a comparison with the expectations from lower redshift is not straightforward. This is because the RL population is composed by a large variety of sources, whose observed properties can be affected by relativistic beaming at different degrees (depending, for example, on the orientation of the relativistic jets) and therefore modify the observed shape of their luminosity function (LF; e.g. Urry & Padovani 1995). For this reason, the single classes of RL AGNs are often studied separately (e.g. Rigby et al. 2011; Diana et al. 2022). However, since it is not possible to exclude that some degree of relativistic boosting is present in DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18 with the data currently available, we estimated the overall number of RL QSOs expected to be found in a given survey using the following approach.

We started from the radio LF derived by Mao et al. (2017) for the flat-spectrum radio quasar (blazar hereafter) population, that is, sources with the relativistic jet oriented close to our line of sight (θview < 1/Γ, where Γ is the bulk Lorentz factor of the jet) and, therefore, for which we expect the radio spectrum to be dominated by the radiation relativistically boosted. The LF derived by Mao et al. (2017) was built using blazars in the redshift range z = 0.5 − 3 and then was confirmed up to z ∼ 5 by Caccianiga et al. (2019). From this LF we created a mock sample of blazars at z > 5 whose optical luminosities were computed based on the optical-to-radio ratio distribution observed in the sample discussed by Caccianiga et al. (2019), which corresponds to the highest redshift complete sample of blazars currently available. In this way we built a sample of blazars for which the redshift, the radio flux density and the optical/NIR magnitude are known (we assumed αr = 0, Padovani 2017, and αo = 0.44, Vanden Berk et al. 2001). By considering different radio/optical limits, we were then able to determine the corresponding number of detectable blazars for a given radio/optical survey combination. Finally, in order to estimate the overall number of RL QSOs starting from blazars, we computed the number of RL QSOs with a misaligned jets whose radio flux density is relativistically de-beamed,9 but still detectable in the given radio survey, following the approach outlined in section 2 of Ghisellini & Sbarrato (2016). As a reference, this last step resulted in an increase of a factor ∼10 in the number of total RL QSOs (with respect to blazars only) for |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}\gt 1$| mJy beam−1 and 5.9 < z < 6.4.

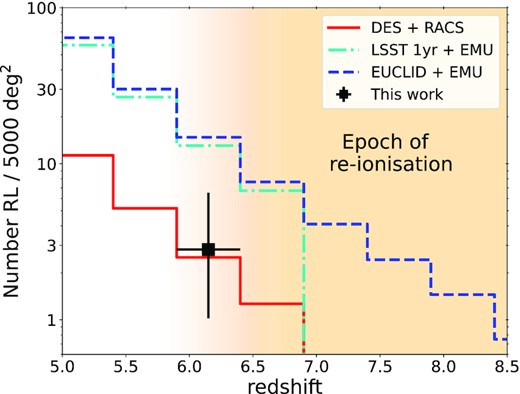

In Fig. 5, we show the expected number of RL QSOs per bin of redshifts to be detectable in different combinations of radio + optical/NIR surveys. In particular, in the radio band we considered RACS (limit 1 mJy beam−1; Hale et al. 2021) and the EMU survey (limit 0.1 mJy beam−1; Norris et al. 2021), while in the optical band we considered DES (limit mag(z-band) = 21.3, as in this work), the Vera C. Rubin Legacy Survey of Space and Time (VRO/LSST; limit mag(z-band) = 23 after the first year; Ivezić et al. 2019) and the Euclid wide survey (limit mag(NIR) = 24; Euclid Collaboration 2022). Moreover, in the case of DES and VRO/LSST, we only show the expected number of sources up to z = 6.9, since the wavelength coverage of these surveys will not allow for the detection of objects at higher redshift.

Expected number of z > 5 RL QSOs per redshift bin in different combinations of current/future radio + optical/NIR surveys rescaled to an area of 5000 deg2. The sensitivities adopted for the different surveys are the following: DES mag (z-band) = 21.3, VRO/LSST 1 yr mag (z-band) = 23, Euclid–WIDE mag(NIR) = 24,.

RACS |$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}$| = 1 mJy beam−1 and EMU |$S_{\rm 944\, MHz}$| = 0.1 mJy beam−1. In the redshift bin 5.9 < z < 6.4 we also show the constraints derived from the discovery of the two new RL QSOs from the RACS + DES combination discussed in the work. The estimate has been corrected for the completeness of the selection described in Section 2, while the upper error is given by the completeness-corrected number of candidates we selected from RACS.

Based on the extrapolations from lower redshift, the number of expected RL QSOs with S|$_{\rm 888\, MHz}\gt 1$| mJy beam−1 and mag (zDES) < 21.3 at 5.9 < z < 6.4 is about three. This is broadly consistent with the discovery of two new RL QSOs at ∼6.1. Indeed, by taking the completeness of our selection into account (∼71 per cent, see Section 2), the expected number of sources is |$2.8_{-1.8}^{+3.7}$| (black square in Fig. 5), where we computed the upper error by considering the total number of high-z candidates found in this work from RACS.

Based on Fig. 4, if we consider instead the upcoming EMU and VRO/LSST surveys, we expect to increase the number of RL QSOs up to z ∼ 6.5 by more than an order of magnitude. This is due both to the deeper sensitivities, in the radio and in the optical/NIR bands, as well as to the much larger common area (the entire southern sky; Norris et al. 2013; Ivezić et al. 2019). However, the VRO/LSST, similarly to DES, will only be sensitive to sources up to z ∼ 7, after which we expect all the optical emission of QSOs to be redshifted at wavelengths outside the grizY filters. At the same time, other complementary surveys such as the Euclid wide survey, with filters also in the NIR (YJH), will reach a similar magnitude limit at higher wavelengths (e.g. Euclid Collaboration 2019) and therefore, together with the EMU survey, they will be able to explore the RL QSO population up to z ∼ 8.5.

5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

We have presented the selection of a sample of high-z RL QSOs in the southern hemisphere based on their optical/NIR colours as reported in DES and their detection in the RACS radio survey. We set the selection criteria such that we were able to recover almost all previously discovered QSOs in the same area above our optical/radio flux limits. The completeness and the efficiency of our selection, mainly driven by the radio catalogue for the association, will significantly increase with the upcoming RACS data releases.

From the sources selected in this work, we were already able to identify two new high-z RL QSOs: DES J0320−35 at z = 6.13 ± 0.05 and DES J0322−18 at z = 6.09 ± 0.05. These are now two of the most distant RL QSOs currently known. Indeed only a few z > 6 RL QSOs have been detected in the radio band (e.g. Gloudemans et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2021) and even fewer are confirmed as radio-loud (e.g. Bañados et al. 2021; Gloudemans et al. 2022). Interestingly, both sources do not present prominent broad emission lines, suggesting that they are both WLQSOs. If confirmed by NIR further spectroscopy, this would further strengthen the increase of the WLQSOs fraction at high redshift recently hinted both in the RQ (e.g. Bañados et al. 2016; Shen et al. 2019) and the RL (e.g. Gloudemans et al. 2022) QSO populations and therefore imply an evolution of SMBH accretion conditions/modes at high redshift.

By comparing the number of selected and confirmed candidates to the expected number of RL QSOs at 5.9 < z < 6.4 with the same flux density cuts (|$S_{\rm 888\, MHz}\gt 1$| mJy beam−1 and mag(zDES) < 21.3), we found that the discovery of DES J0320−35 and DES J0322−18 is consistent with expectations. Moreover, we also showed how the upcoming wide-area surveys (e.g. VRO/LSST, Euclid wide, and EMU) can increase the number of RL QSOs at z > 5 by a factor >10 and potentially reach sources up to z ∼ 8.5. Combined with samples of high-z radio galaxies selected with different techniques (e.g. Saxena et al. 2018a,b, 2019; Drouart et al. 2020; Broderick et al. 2022), these sources can be used to address important questions of modern astrophysics: on the formation and growth of SMBHs (e.g. Overzier 2022), the evolution of relativistic jets properties (e.g. Ighina et al. 2022a), their impact on the environment (e.g. Hardcastle & Croston 2020) and the properties of the IGM in the early Universe (e.g. Carilli et al. 2004; Furlanetto, Oh & Briggs 2006).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the referee for their suggestions that have improved the quality of the paper. This work is based on observations obtained at the international Gemini Observatory, a program of NSF’s NOIRLab, which is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation. On behalf of the Gemini Observatory partnership: the National Science Foundation (United States), National Research Council (Canada), Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (Chile), Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Argentina), Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (Brazil), and Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (Republic of Korea).

In this work we made use of the Gemini iraf package. IRAF is distributed by the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.

We acknowledge financial contribution from the agreement ASI-INAF n. I/037/12/0 and n. 2017-14-H.0 and from INAF under PRIN SKA/CTA FORECaST. We acknowledge financial support from INAF under the project ‘QSO jets in the early Universe’, Ricerca Fondamentale 2022.

This research made use of astropy (http://www.astropy.org) a community-developed core Python package for Astronomy (Astropy Collaboration 2018). This research has made use of the VizieR catalogue access tool, CDS, Strasbourg, France (DOI: 10.26093/cds/vizier). The original description of the VizieR service was published in 2000, A&AS 143, 23.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All of the data used in this work are publicly available as described in the text. The DES catalogue can be retrieved from the corresponding SQL portal (https://des.ncsa.illinois.edu/desaccess/home), while the RACS source lists used for the radio association can be found on the CASDA portal under the AS110 project code (https://data.csiro.au/domain/casdaObservation?redirected = true). Reprocessed data are also available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Following the literature, we define a source to be RL if its rest-frame radio loudness R = S5GHz/S4400Å > 10. Even though it has been shown that this classification might be too simplistic for the definition of QSOs with relativistic jets, it should include all the most powerful radio jets (e.g. Padovani 2017).

Available at: https://des.ncsa.illinois.edu/desaccess/home.

To assure a reliable non-detection in this band we first considered only candidates with mag_auto_g >23.5 and magerr_auto_g >0.3. Then, after having applied all the other selection criteria, we checked the single g-band images and discarded all the sources where a S/N ≳ 3 signal was present.

Available from the CASDA website: https://data.csiro.au/domain/casdaObservation?redirected = true.

Available at: http://ast.noao.edu/sites/default/files/GMOS_Cookbook.

See http://casu.ast.cam.ac.uk/surveys-projects/vista/technical/filter-set and https://wise2.ipac.caltech.edu/docs/release/allsky/expsup/sec4_4h.html for the conversion factors from Vega to AB system for the VHS/VIKING and WISE filters, respectively.

Here we only consider the observations in the wide-band 200–231 MHz image, which provide the strongest constraints.

The (de-)amplification factor scales as ∝ δp, where the Doppler factor, δ, is given by [Γ(1 − βcosθview)]−1 and p = 2 + αr (e.g. Cohen et al. 2007).