-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Agnieszka Jagodzińska, The Periodical Olam Katan (1901–1904) and Its Readers: A Study in Modern Jewish Childhood in Eastern Europe, Modern Judaism - A Journal of Jewish Ideas and Experience, Volume 45, Issue 1, February 2025, Pages 52–78, https://doi.org/10.1093/mj/kjaf002

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Olam Katan [Small World] was the first illustrated Hebrew periodical for children, edited by Avraham Leib Shalkovich (aka Ben-Avigdor) and Shmuel Leib Gordon (aka Shalag). It was published first in Vienna (1901–1902) and then in Cracow (1902–1904). This article reconstructs the readership of this periodical through the analysis of a unique source: a collection of children’s letters sent to Olam Katan and printed in its pages. Children’s Zionist culture is studied as reflected in the readers’ correspondence. Applying quantitative and qualitative methods, and methods of digital humanities and spatial analysis, this article reconstructs the geography, age, and gender of the readers of Olam Katan, setting them in the broader context of modern Jewish childhood in Eastern Europe.

INTRODUCTION

Until 1939, Warsaw was home to the world’s most vibrant and diverse Jewish press, published in various languages and representing various political and cultural viewpoints. While the ideological affiliations of these periodicals can be reconstructed through their content, it is more difficult (and sometimes impossible) to define precisely who the periodicals’ readers were.1 We can make an educated guess about the audience to which a given magazine or newspaper marketed itself, but it is rarely possible to identify information such as the readers’ places of residence, gender ratio, or age. Lists of subscribers to the Jewish press are largely gone, unless for some reason they were published.

This paper intends to fill a small part of this vast void in historians’ knowledge about readers of the Jewish (and, more precisely, Hebrew) press at the beginning of the 20th century in Warsaw. My analysis focuses on the first illustrated Hebrew periodical for children, a weekly journal titled Olam Katan [Small World],2 which was published first in Vienna (1901–1902) and then in Cracow (1902–1904) by Warsaw-based editors Avraham Leib Shalkovich (aka Ben-Avigdor), a writer and the founder of the renowned Tushiya Publishing House, and Shmuel Leib Gordon (aka Shalag), an educator and writer. Olam Katan was only one of Ben-Avigdor’s many endeavors to contribute to the “Hebrew revival”3 and promote Zionism. Re-vernacularization of the Hebrew language was tightly linked to a project of raising a new generation of children who could use Hebrew in everyday life.4 Ben-Avigdor’s strategy was to create young Hebrew readers at a time when such readers and such literature were scarce.5 This article will shed light on who some of these children were.

There is a unique source that can be used to glean information about the periodical’s readers: a collection of 389 children’s letters sent to the editors and printed on its pages. There are several reasons why this material is special. First, there are not many sources that identify readers of the pre-war Jewish press. Readers’ correspondence printed in Olam Katan provides us with a rare opportunity to get to know the actual boys and girls who read the periodical and participated in early Zionist Hebrew culture. It offers insight into how these young people learned, played, worked, or organized their free time, how they celebrated their holidays, and what they believed in and hoped for. The correspondence provides information on the readers’ place of residence, age, gender, education, family situation, and many other aspects of their lives. Moreover, this collection of letters is unique, as there are not many texts written about childhood by children who are not yet adults. Ego-documents that include narratives on childhood, like autobiographies, are characterized by diachrony, as they introduce a chronological distance between the child-self and adult-self. Children’s letters represent synchrony of the writing-self and child-self. As David Assaf and Yael Darr noted, such ego-documents:

“are extremely rare. This is primarily because children do not tend to reveal their personalities and inner worlds through writing but rather through speech or actions. Moreover, even when children do produce ego-documents, such as personal letters, diaries, or school compositions, few are preserved, since, unlike adults, children lack awareness of the historical value of preservation and documentation.”6

Children, especially those belonging to lower classes, also lacked the means to preserve their ego-documents. Of course, studying this kind of text presents several challenges—some typical for all ego-documents, some pertaining exclusively to those written by children.7

In any case, sources which record children’s voices are largely a modern phenomenon, as is the concept of childhood as we know it today. If we use “modern” and “modernity” in reference to the fundamental changes in Jewish life in the 19th century, some commentary is needed. In this paper, I adopt the approach of Ekaterina Oleshkevich, who in her research on Jewish childhood in late imperial Russia criticizes the use of “tradition” and “modernity” as dichotomic categories of analysis. In this respect, she follows the postulate of Gershon David Hundert, who pointed to a more complex dynamic of change and stasis in the history of Jews in Eastern Europe than those in Western Europe.8 This approach recalibrates the approach to studying Jewish childhood in Eastern Europe, where patterns of modernity were not the same as in the West because the “modern” often coexisted with the “traditional,” challenging tradition to reinvent itself rather than be replaced. Oleshkevich encourages historians to not only focus on the result of changes, but also on the process of change itself—to “examine these shifts in their complexity and unevenness, concentrating on small differences, intermediate forms, and non-linear developments, as well as the influences of various factors.”9

Following this approach, I study the formative process of early children’s Zionist culture as reflected in children’s correspondence in Olam Katan in the early years of the 20th century, when Hebrew language and culture were still in their pre-vernacular phase. I attempt to reconstruct the geography, age and gender of the readership of the periodical, setting them in the broader context of modern Jewish childhood in Eastern Europe.

SOURCES AND METHODS

As mentioned above, the main source of this analysis is correspondence readers sent to Olam Katan, which the periodical then printed. I have analyzed every issue of this periodical published between 1901 and 1904, using the traditional or digital collections of four libraries: the Jagiellonian Library in Cracow, the National Library in Warsaw, the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, and the Libraries of Tel Aviv University. Some of the issues were damaged (having missing or torn pages), but luckily their number was very low; therefore this lost or damaged content does not challenge the outcome of the analysis presented here.

The correspondence was published in a section titled Ḥalifot mikhtavim bein korei ha-Olam ha-Katan [Exchange of letters between Olam Katan’s readers], or simply Mikhtavim [Letters], which appeared on the last pages of an issue. The majority of the issues (104 out of 15510) contained readers’ correspondence, but there was a visible decline in their numbers over the years.11 The decreasing number of issues with a correspondence section was not counterbalanced by a rise in the number of letters printed; there was also a steady decline in the total number of letters (389 altogether). In the first year of publication, there were 191 letters from readers, 113 in the second year, and 76 in the third year. In the last six issues, which appeared in the final year of publication, there were only nine.12

A few factors can explain the decline both in the number of issues containing a correspondence section and in the total number of letters. The editors’ efforts to provide young readers with a platform where they could share their experiences, hopes, and aspirations with their peers was especially important in the first year of the periodical’s publication, when it was essential to build a community of readers. Letters also demonstrated that Olam Katan was widely read by children and young people, which served the periodical’s self-promotion—very much needed at its outset. Perhaps the decision to curtail the publication of letters was dictated by the repetitiveness of the content: generally, the letters were about children’s education and pastimes, especially learning Hebrew, their Zionist activities, their aspirations, or their reactions to current events. The drop in the number of printed letters might have also reflected a more general tendency in the Hebrew press, which printed readers’ correspondence less often in the beginning of the 20th century than in the 19th century.13

Of course, the editors of Olam Katan presumably received more letters than they were able to publish.14 Additionally, not every child who read the periodical wrote letters to the editors. The collection of correspondence at our disposal today represents only a selection of letters by the most active readers of the periodical. Therefore, whenever I refer to statistics of “readership” in this study, I always mean only this dedicated group of readers. Unfortunately, there is no way to study the broader group of children who remained only passive consumers of Olam Katan. But, it is obvious that the total number of readers was higher (sometimes considerably so) than the number of correspondents or even subscribers to a given periodical, as multiple readers would commonly share issues of periodicals.15

We have no evidence of whether adults (perhaps teachers or family members) assisted children in writing these letters, or if they were later altered by editors. Thus, it is difficult to assess children’s agency as authors. The language style is rather simple, and there are also occasional mistakes or typos, but it is hard to say whether they were a child’s or a typesetter’s doing. Regardless of the unsolved problem of determining children’s agency and autonomy in writing this correspondence, the letters still unquestionably provide data that uniquely shape our knowledge of who these children were, such as their geography, age, and sex. The readers’ letters are by no means a perfect source, but they can get us as close to these readers (or at least to a part of them) as is possible today.

The methods used in my analysis are both qualitative and quantitative. This paper is not the sole study devoted to readers’ correspondence in Olam Katan,16 but it is the first one to employ methods of statistics and digital humanities, including spatial analysis. To create the database I used to map the geographical outreach of the periodical, I studied both the correspondence section in Olam Katan and the section Pitronei ha-ḥidot [Riddles’ solution], in which the editors announced the names (and sometimes place of residence) of children who had successfully solved riddles and puzzles published in the periodical.17 The database recorded some 350 cities, towns, villages, or settlements. The Hebrew or Yiddish spelling of non-Jewish (mostly Slavic) town names, at times misspelled or spelled in various ways, presented a challenge, but the majority of them (293) were successfully identified and placed on the map. The remaining cases of unsuccessful identification do not, in my opinion, challenge the general geographical profile of the periodical’s readership presented in this study.

To analyze the gender and ages of readers, I used only the children’s letters. The reason I excluded Pitronei ha-ḥidot from this analysis was that it did not include information on children’s ages, and I could not always identify gender because gender-revealing first names were sometimes shortened only to initials. Children’s names also appeared in the section Nedavot [Donations]. However, this section was excluded from my database because it was unclear if those who donated were readers of Olam Katan. It stands to reason that the names of some of the children might have appeared only because they donated money to the funds raised by other children, who had a closer connection to the periodical, and not because they themselves were readers of the journal.

GEOGRAPHY

Olam Katan is an interesting chapter in the history of the Eastern European press, Jewish and non-Jewish alike. It was published as a children’s periodical in Hebrew at a time when there were practically no Jewish children who used Hebrew as a vernacular language.18 Its aim was to promote Hebrew culture, and yet many of the texts published in its pages were translated from other languages.19 Its geography was also full of paradoxes. As mentioned, both of the editors, Ben-Avigdor and Gordon,20 were based in Warsaw (the Kingdom of Poland), which was also the seat of Ben-Avigdor’s Tushiya Publishing House. Yet the periodical was published first in Vienna and then in Cracow, within the borders of Austria-Hungary, and most of Olam Katan’s readers lived in the Pale of Settlement in Tsarist Russia. But the most important geographical orientation in the ideology of both the periodical’s creators and readers was Eretz Yisrael, or Palestine, then under Ottoman rule.

This section explores how the logistics of publishing this periodical were intertwined with the political and symbolic geography of Olam Katan’s editors and readers. Additionally, spatial analysis of the periodical’s outreach helps to identify the child readers and, by mapping nearly three hundred towns from which their correspondence was sent, contributes to our knowledge about the geography of the Hebrew press in general. I also consider a possible correlation between the geography of readers and the region’s network of railways, which was the most modern means of overland transport in the early 20th century, and attempt to assess how it might have influenced the distribution of the periodical and activity of its readers.

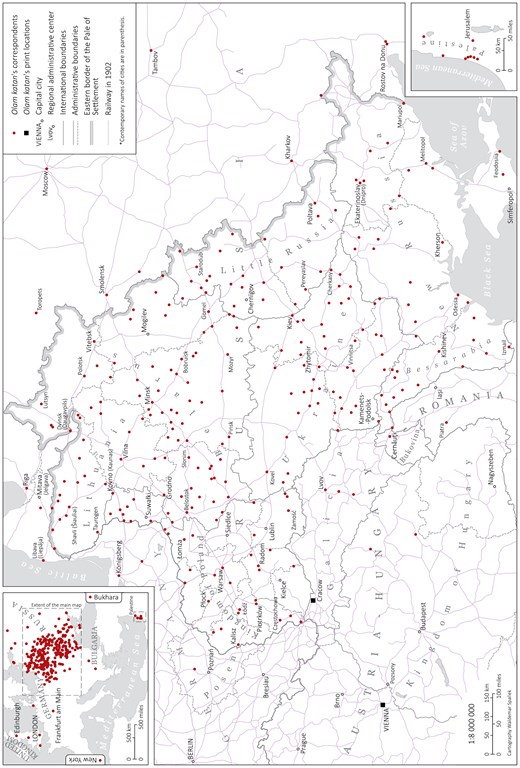

Map 1 shows all the identified locations21 from which children’s correspondence to Olam Katan was sent.22 The greatest concentration of readers appears in the Pale of Settlement, formed by the western provinces of the Russian Empire annexed during the Partitions of Poland (1772–1795) and by the southern provinces of Bessarabia, New Russia and Crimea, which Russia also annexed in the 18th century. The second biggest concentration was in the Kingdom of Poland. The map records only a few locations in Galicia and Hungary (both in the Austro-Hungarian Empire), in Russia proper, and in Romania, Germany, and England. Palestine was also an important center outside Europe. There are no records from Vienna, nor from Cracow, which confirms that both these cities were chosen only as places of print.

The furthest that Olam Katan reached in the west was New York, in America; to the north, it reached no further than Belozersk in Russia, while Bukhara was its furthest outpost to the east, and the settlement Beer Tuvia (Kastina) in Palestine was its furthest south. It should not surprise us that the press created in Eastern Europe was read far beyond it. The list of subscribers to another periodical, Ha-Tsefira (also published in Warsaw), reveals that it was not uncommon for the Hebrew press to cross many borders to reach its readers. The outreach of Ha-Tsefira, was even more impressive. It was read in both Americas, Africa, and even Australia.23

The geographical outreach of Olam Katan (cartography by Waldemar Spallek).

The geographical profile of Olam Katan corresponds with what we know about the adult readership of the Hebrew press. As Vladimir Levin demonstrated in his analysis of subscriptions to the aforementioned Ha-Tsefira in 1912, this newspaper was most widely read by Jews living in the Pale of Settlement. In the south-western provinces of the Russian Empire and in the territory of present-day Lithuania and Belarus, Hebrew knowledge was more widespread than in other regions, and readers preferred Hebrew to Russian periodicals.24 So the geography of the core readership of Ha-Tsefira and of Olam Katan overlapped. Moreover, it is only natural to assume that the young people who read this Hebrew children’s periodical between 1901 and 1904 later shifted to reading the Hebrew press for adults, and by 1912 might have been among the readers of Ha-Tsefira.25

Map 1 shows another important aspect of Olam Katan’s distribution: its dependence on the railways. The development of rail transport in the 19th and early 20th centuries changed many aspects of Jewish (and non-Jewish) social and economic life. More efficient transportation meant that the press could be more widely and quickly distributed. This was especially important in the case of Olam Katan, whose printed issues had to travel to readers in the Pale and the Kingdom of Poland, first from Vienna, then from Cracow. What persuaded Ben-Avigdor to have the periodical printed so far from his Warsaw publishing house? Although I did not find any archival sources that could help interpret Ben-Avigdor’s decision,26 the general hardship of securing a license for publishing a new periodical in the Kingdom of Poland could explain this strategy. Getting permission to print a new periodical in Polish was itself difficult, and publishing in Jewish languages was even more so. Ben-Avigdor probably had to resort to the same tactic that other editors in the Kingdom of Poland did in this situation: they used printing houses in western Galicia and then transported the issues to Poland or elsewhere.27

To have Olam Katan and his other periodicals printed in Cracow28 (not to mention the first year of printing Olam Katan in Vienna), Ben-Avigdor needed to rely on the railway, which was essential to the logistics and transportation of these periodicals. As Map 1 shows, most locations were either situated directly on train routes or in close proximity to them.29 Although railways facilitated Olam Katan’s distribution, it still suffered from delays. This, together with some apparent financial losses, eventually forced Ben-Avigdor to discontinue the children’s periodical and his other periodicals, too.30

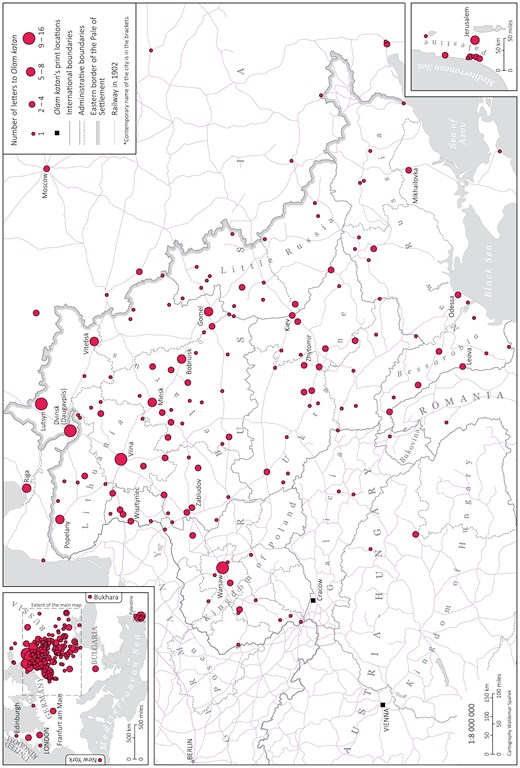

While Map 1 displays all the locations from which readers sent letters and riddle solutions later published in the periodical, Map 2 visualizes the number of letters sent from each place.31 The second map is based on letters only, 344 letters specifying the location of their writers, sent from altogether 175 locations. Olam Katan received and published only one letter from most (109) locations and received 2–4 letters from another 55 locations. Only eleven locations yielded five letters or more: seven locations with five to eight letters, and four locations with nine to sixteen letters. There are no archival sources that reveal the editors’ policy governing the selection and publication of letters, so we cannot really know if readers from “one-letter-only” locations wrote to Olam Katan only once. Places with two to four letters suggest more serious engagement with the periodical, perhaps paired with other Zionist activities. Map 2 shows that the majority of Jewish children in Europe who had their letters published in the periodical (whether it was only once or frequently) lived in the territory of present-day Lithuania and Belarus (with some additional locations in southern Latvia and Warsaw in Poland), in the area spreading roughly between Warsaw, Gomel, and Riga. Of the seven cities from which Olam Katan received five to eight letters, only one (Jerusalem) was situated outside Eastern Europe. The remaining six—Bobruisk, Gomel, Minsk, Popelany, Riga, and Vitebsk—were all located in the above-mentioned area.

Readership of Olam Katan according to the number of letters (cartography by Waldemar Spallek).

The four locations with the highest number of published letters (more than 9) were Warsaw (16), Vilnius (14), Lutsin (11), and Dvinsk (9), now known as Daugavpils in Latvia. Though their populations differed considerably in size, all were located either directly on the Warsaw–Petersburg railroad line (Warsaw, Vilnius, Dvinsk) or in close proximity to it (Lutsin).32 This quantitative analysis could indicate that these cities had a stronger, better organized group of correspondents to Olam Katan and, by extension, a vibrant Zionist movement among the youth. This was true in the case of Lutsin33 and Dvinsk;34 the correspondence from various individuals in these two cities confirms they had developed local Zionist initiatives. However, in the case of Warsaw and Vilnius, qualitative analysis points to additional factors that explain the high number of letters from these cities. In Warsaw, six of the sixteen letters were penned by Moshe Gordon (including two co-signed by his brother, Yehoash). The Gordon brothers were sons of the periodical’s co-editor, Shmuel Leib Gordon. In Vilnius, eight letters out of fourteen were sent from the same family—five penned by Ḥana Goldberg, one by Yehudit Goldberg, and two more were co-signed by both sisters. Ḥana and Yehudit were daughters of Israel Leib Goldberg (1860–1935), a prominent figure in the pre-Zionist and Zionist movement and a great philanthropist. His wife, Rachel, was a co-founder of Yehudiya Hebrew Girls School.35 These two cases demonstrate that although the world of Olam Katan stretched between Bukhara and New York, it was in fact a “small world.” The connections between friends, colleagues, and families in adult Zionist circles were reflected in the children’s periodical.

In comparison with Map 1, which demonstrated the general geographical outreach of Olam Katan, Map 2 shows that the readers in the northern part of the Pale engaged more actively with the periodical, as measured by the number of published letters. The concentration of locations in and around the southern part of the Pale (spreading roughly between Zamość, Kharkov, and Odessa) that is visible on Map 1 is not equally represented on Map 2. The concentration of more active readers in Belarus, Lithuania and part of Latvia corresponds with the characteristic profile of Jewry from this territory, who historically represented a mitnagdic tradition within Judaism different from the southern part of the Pale, which was more under the influence of Hasidism. Jews in the north were also more open to modernizing trends and to social and political activism; they adopted different patterns of both religious and secular education, and, last but not least, more eagerly embraced proto-Zionist and Zionist ideology and its commitment to re-vernacularize Hebrew.36 The visible difference on the map between the northern and southern part of the Pale corresponds with a more general geographical pattern of Jewish ego-documents in Eastern Europe.37

There is one more aspect of spatial analysis that deserves a closer examination: Eretz Yisrael. Altogether, Olam Katan published seventeen letters from eight locations in the region of Palestine, so it was close to the number of letters received from Warsaw alone. Jewish children wrote from Gedera, Jerusalem, Kastina (Beer Tuvia), Mikve Israel, Rehovot, Rishon Le-Tsiyon, Rosh Pina, and Zikhron Yaakov. Although letters from this region were not numerous, they held a special significance for the periodical and its readers. In Zionist ideology, the political and social geography did not matter as much as the symbolic geography of which Eretz Yisrael was the center. In their letters, children living in the diaspora expressed their hopes and dreams of emigrating to the land of their forefathers, speaking Hebrew, cultivating the soil, planting orchards, and other idealized Zionist activities.38 Those already residing in Eretz Yisrael were a living example that these dreams could come true. Letters sent from there demonstrated how the Yishuv was putting Zionist ideology and the Hebrew language into practice.

Confrontations between the Zionist dream and the practicalities of Jewish life in Eastern Europe sometimes provoked disillusionment among children. For example, Eastern European Zionist children were happy to learn Hebrew, but they were surprised or even shocked to discover they had learned a “wrong” kind of Hebrew: the pronunciation of the Ashkenazi Hebrew, which most of these children acquired, was so different from the Sephardic pronunciation ultimately chosen as the standard for Modern Hebrew that it was an obstacle in oral communication. In 1903, a reader named Tsvi Levinski reported that when three guests from Eretz Yisrael visited his family in Odessa and all started to speak in Sephardic Hebrew, he could not comprehend them well. The guests told him that this was how Hebrew was spoken in Eretz Yisrael. Clearly puzzled by this discovery, the boy asked in his letter to Olam Katan if there were children “here, in our country [i.e. Russia]” who could understand and speak this kind of Hebrew.39

Regardless of these occasional troubles with oral communication, Olam Katan, as a written form of mass communication, provided children living in various territories with a platform to meet and share their experiences. It was a modern means of mass communication that connected Jewish children across regions, countries, and continents. The distribution of the periodical also depended on modern means of mass transportation, such as railways, that facilitated both the distribution of Olam Katan and readers’ engagement with the periodical. It is interesting to note that the geographical outreach of the periodical in Eastern Europe was not limited to big cities that were important centers of Zionist culture (like Warsaw or Vilnius) but also extended to towns and villages. Letters from readers demonstrate that early children’s Zionist culture in this territory was not just an urban phenomenon.

GENDER

Olam Katan was theoretically directed to Jewish children of both sexes, boys and girls alike.40 However, beginning with the first editorials there were hints that boys were the periodical’s expected target group more so than the girls.41 Nevertheless, Ben-Avigdor admitted that “there are numerous boys—and also girls lately—who possess sufficient knowledge of our [i.e. Hebrew] language.”42 His observation refers to the outcome of changes in the traditional Jewish education system, which in his time was still defined by gender. Transformations that took place over the course of the 19th century, especially in its second half, brought forth new forms of schooling (both private and governmental) that did not replace cheders (traditional religious schools, mostly for boys) nor put an end to gender segregation, but did result in a new approach to teaching Hebrew.

As Eliyana R. Adler shows in her research, in traditional cheders in Russia boys learned Hebrew texts by translating them to Yiddish, but did not receive any proper language instruction. The first schools for girls used a similar approach. By the 1850s most of them included “Hebrew” in their teaching programs, which meant deciphering Hebrew texts without comprehensive language learning, but by the 1860s there were already some schools for Jewish girls that started providing Hebrew language instruction. Private school for girls—contrary to governmental school for boys (that functioned until 1873) and traditional cheders—offered educators more liberty and a chance to experiment with teaching Hebrew as a language. Hebrew instruction became an important part of the curriculum in a new type of Jewish school which emerged in the end of the 19th century—the cheder metukan [a reformed cheder].43 In these schools, popularized by Zionism, Hebrew instruction had a special place, as it served the planned re-vernacularization of the language.

As attested by letters in Olam Katan, many children writing to the periodical were educated in this new type of school. But although cheder metukan offered education for both sexes, girls learning Hebrew were still in the minority. This gender inequality is consistent with the ratio of Jewish boys and girls writing to Olam Katan: 73 percent of letter authors were boys and only 27 percent were girls. This ratio seems to follow a more general trend in Jewish ego-documents in Eastern Europe, as suggested by Ekaterina Oleshkevich’s selection of autobiographies in which the male-to-female author ratio is 75.5 percent to 24.5 percent.44 The autobiographies sent for the YIVO contest confirm this trend, too (75 percent to 25 percent).45 A corpus of Zionist children’s letters from Nowy Dwór from a later period (1934–1935) still shows an overrepresentation of boys, but the gender ratio is slightly more balanced at 62 percent to 38 percent.46

The readers of Olam Katan noted and commented on the unequal gender division. Ḥana Grinberg from Berdichev (age 9) was surprised to see more boys than girls reading the Hebrew children’s periodical, which stood in contrast to another Russian periodical for children that she also read.47 Brothers David (10) and Zeev (8) Shenvits from Płock were amazed to read a letter from a girl, Ḥana Shevel, and inquired about her Hebrew learning48 which suggests it was not a common case (at least not in Płock). Baruch Hilel Raiskin (13) from Borispol was happy to see girls writing in Hebrew, but at the same time admitted that Hebrew-educated boys outnumbered girls. Yet he encouraged girls to learn the language, reminding them, “You have to know, sisters, that only then our language will become living if you will be able to speak Hebrew, too.”49

Girls reacted with joy upon discovering that there were other girls who knew Hebrew,50 and they evidently sought contact with them, which suggests that they must have felt alone in their own environment. This is well illustrated by a 1903 letter from Sara Rivka Mendelev, in which she confessed that, at first, everyone in her village laughed at her and claimed only boys could study Hebrew. Later, however, the situation improved; she shared Olam Katan among her peers, showing them how useful and beautiful this periodical could be, and proving that girls in other places were also learning and speaking Hebrew. Although this changed her peers’ attitudes, Sara Rivka still felt lonely in her village without educated companions she could speak in Hebrew. According to her letter, were it not for her old father who taught her Hebrew, she would have been as "ignorant" as the rest of the local girls.51 So what Olam Katan had to offer to Jewish girls like Sara Rivka was much more than interesting stories and beautiful images—it gave them a sense of belonging to a bigger community and “provided them with virtual companionship and assurance, against the background of a skeptical atmosphere.”52 As Meirav Reuveny noted, “The Hebrew children’s magazines were, to my knowledge, the first platform that allowed this pioneering generation of girls to join Hebrew public discourse and to express themselves and reflect on the meaning of their gender.”53

Girls writing to Olam Katan were self-confident and did not need to justify why they learned Hebrew. In this forum, it was obvious. Some of them were even bold enough to criticize the editors for not paying enough attention to the needs of their female readers. Such concern was raised in one of the letters written by the aforementioned Ḥana Goldberg from Vilnius, who was one of the periodical’s most active correspondents. In 1902, she complained:

Among all the stories, there is hardly a story relating to the life of girls. All the authors write only about the life of boys: their joys and sorrows, their industriousness and laziness, etc. And about the life of girls, nobody writes nor speaks, and why so? Girls also read and understand no less than boys, and their life is filled with very interesting dreams. Therefore, I ask the editors, also on behalf of all the girls who read Olam Katan (and who surely would desire this) that they would be so kind as to give us in the coming year stories and scenes54 from our life, [relating to] us, girls. And how good would it be, if the stories were written by female writers and not male, because who knows [better] than a woman all the details of our life!55

It seems that the editors took this complaint seriously, as more stories appeared later featuring girl characters like Gibora tseira [A young heroine],56Ha-tsoanit ha-ivriya [The Jewish Gipsy-girl] by Yehuda Steinberg,57 an autobiographical story of Ḥemda Ben-Yehuda,58 and Ha-naara ha-gibora [The teenage heroine], Edmondo di Amicis’ translated story.59

Girls writing to Olam Katan proved that the Hebrew education they received in private schools or at home was successful. Their presence in early 20th-century Hebrew culture, which for so long had been a men’s club, was a significant herald of further changes. And yet, although these girls challenged centuries-old gender norms in education, in other aspects of their lives they still functioned within traditional gender roles.60 The question of gender and education proves that evolution and stasis were intertwined. The reformed schools not only inspired change in their own pupils, but also forced the “traditional” cheder to reinvent itself. As Oleshkevich argues, the cheder “evolved in order to stay relevant and silently absorbed some of the Maskilic principles. As a result, a broad spectrum of different educational options emerged, fitting the needs of the different social groups in Jewish society. By the early 20th century, there was not one single cheder, but many cheders.”61The change also manifested in the cheder’s approach to teaching Hebrew as a language and using Hebrew textbooks.62

AGE

Olam Katan carried the subtitle Iton shevui metsuyar li-venei ha-neurim,63 “A weekly illustrated paper for the young.” This section will attempt to answer the question of exactly how young the readers were and how the editors negotiated the periodical’s content in order to accommodate readers of various ages.

Letters in the correspondence section did not always include the age of the children who penned them. Nevertheless, I was able to create a database of 200 readers who either provided their age in their letters or whose ages could be verified through archival or other sources. In the statistics presented below, I include letters penned by one author or co-authored by two or three children. Letters sent by more than three authors were excluded from the statistics because of the diminishing probability of equal participation by each child in the letter-composing process.64 If a child wrote several letters in a given year of publication, their age was counted only once, regardless of the number of letters sent. However, if the same child wrote a letter in the subsequent year of publication, when they were already one year older, then their age was counted again. Ages like 7.5 were rounded up to 8. If information on age was not provided explicitly, but a person who wrote a letter could be identified by other sources, then their age was reconstructed. School grade was not used as a basis to estimate age as it might not always correctly translate to the pupil’s age—there was no way to verify the age at which a child was sent to school in the first place.

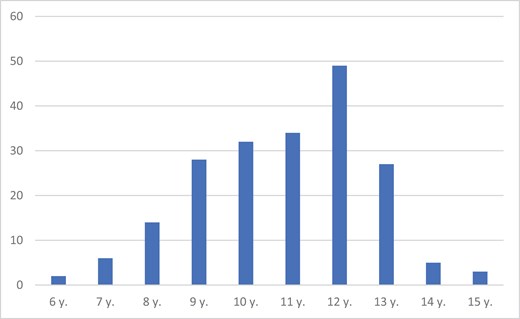

Figure 1 presents the age statistics of Olam Katan’s readers based on their letters to the editors.

The chart’s data capture the rhythm of traditional Jewish education and upbringing. The earliest education of Jewish children, mostly boys, started at the age of five and reached its climax at the age of thirteen when, according to the Jewish religious law, a boy who passed a ceremony of bar mitsva was considered an adult, responsible for his actions and obliged to fulfill the religious commandments.65 As demonstrated by Figure 1, the youngest readers (6–8 years) and the oldest (14–15 years) were the least represented age groups within the periodical’s audience. It stands to reason that the youngest lacked sufficient Hebrew knowledge to be full-fledged readers, not to mention to write letters to Olam Katan, while the older ones considered themselves too mature to read a children’s periodical. However, both these groups constituted only 15 percent of the total audience. Most readers were young people between 9 and 13 years, who constituted the remaining 85 percent of the audience.

How prepared was Olam Katan to meet the needs of readers in various age groups? The editors used materials in original Hebrew or translated/adapted from other languages both for readers’ (self)education and entertainment. As suggested by numerous letters, the children and teenagers enjoyed the periodical’s stories, indicating that the editors succeeded in curating content suitable for their core audience. Additionally, outside of the periodical, there is evidence that Olam Katan offered attractive reading material. In David Zabludovsky’s memoir Fargangene Yorn [Passed Years], the author reminisces about the time when, urged by his father, he was preparing to read from the Torah scrolls in the synagogue, most likely before his bar mitsva. Zabludovsky confesses that he found secular Hebrew readings for children (Olam Katan included) more appealing than the sacred scrolls.66

However, a closer analysis of readers’ correspondence reveals that this general success was met with challenges. As demonstrated elsewhere, there was a significant difference between the first and the subsequent years of Olam Katan.67 One of the innovations introduced in the second year of publication was the general use of nikud. This system of vocalization helped young readers decipher and comprehend the text. During the first year of publication only some of the texts included nikud, and so the decision to standardize its use meant that, with this new edition of Olam Katan, the editors wished to target a younger audience. While younger readers or readers with less Hebrew competence found it helpful, the older readers sometimes took it more as a hindrance than a hint. For example, in a letter printed in 1903, Moshe Wein from Belitsa complained about using vocalization and admitted that it was easier for him to read texts without it. But Wein likely was an older student, as he reported in his letter that he had learned Hebrew grammar and managed to read the Hebrew Bible twice.68 Responding to his letter, Ben Tsion Aaron Spichinski from Bairamcha (present-day Mykolayivka-Novorosiyska in Ukraine) noted that, for those who still needed to learn Hebrew grammar and had not read the Hebrew Bible even once, reading without nikud presented a challenge.69

In 1903, to satisfy both younger and older readers (which usually meant readers with accordingly lesser and greater Hebrew knowledge), Ben-Avigdor and Gordon decided to publish another periodical geared toward an older audience titled Ha-Neurim: Yarḥon metsuyar li-venei ha-neurim [Youth: An illustrated monthly for the adolescents].70 In this case, ‘adolescents’ meant more advanced and older readers who could follow more complicated texts, with nikud being used only occasionally.71Ha-Neurim’s masthead also suggested a different target audience. While the masthead in the new, easier, and simpler edition of Olam Katan printed from 12 November 1902 onwards presented younger children of both sexes, the masthead of Ha-Neurim pictured two teenaged boys. By publishing this additional periodical, the editors finally realized their original plan to diversify their offer for readers of various ages; a goal they could not achieve sooner due to the still limited circle of subscribers to Olam Katan.72

Did this new periodical siphon off some of Olam Katan’s readership? What little evidence we have suggests something else. Yeshaiahu Avrech from Zhytomir wrote to Olam Katan in 1904 about an association in his city called Dovrei ivrit [Hebrew speakers]. The association had some seventy members (only boys, age 10 and above), and had also managed to fund a library in which boys were meeting, speaking (in Hebrew only), and reading, among other things, Olam Katan and (sic) Ha-Neurim.73 In the same year, Immanuel Hazanov from Khotsimskm, who headed another association, Benei Tsiyon [Sons of Zion], reported that 40 members of his association read, among other publications, Olam Katan and Ha-Neurim.74 These two letters, and some others, suggest that Ha-Neurim provided more advanced Hebrew users with extra reading material but did not replace Olam Katan. Hebrew literature for children was still scarce at this time and all reading material was greatly appreciated.75

When Ben-Avigdor and Gordon began publishing Olam Katan, they entertained the idea that the periodical might also be useful for adult readers who were learning Hebrew (either alone, or with a teacher), or for those who already had some command of Hebrew but found it difficult to read the regular press.76 In other words, they thought about am ha-aretz (uneducated people, i.e., Jewish women and those Jewish men who did not receive proper education in Hebrew). The idea to create a Hebrew periodical for children that would also be read by adults wishing to improve their Hebrew knowledge corresponds perfectly with Ben-Avigdor’s grand vision and his consequent publishing strategy: he desired to make Hebrew the language of home and street, not only of the synagogue; a language of modern literature and not only of traditional religious studies; the language of today and tomorrow, and not only of yesterday. He was ready to invest heavily in raising a generation of future Hebrew readers and speakers, but, at the same time, he refused to give up on the parents of the children whom he wished to educate, and refused to consider them a lost generation.

Unfortunately, there is no proof in the correspondence section that un(der)educated Jewish adults used Olam Katan as Ben-Avigdor generously intended. The only letter I could clearly identify as written by an adult was penned by Julia Sawkings, an English Christian from Budleigh Salterton, who expressed her interest in learning Hebrew and the joy she derived from reading the periodical.77 Such a reader must have come as a surprise to the editors, but nevertheless, they decided to print Sawking’s letter in the correspondence section. Although other letters in Olam Katan do not shed light on the situation of adults learning Hebrew, other material in the periodical adds to our understanding of this situation in the context of everyday communication. The autobiographical account Le-toldotai [The story of my life] by Ḥemda Ben-Yehuda, the second wife of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda—who many considered the symbol of the “Hebrew revival”78—is a moving story of an adult woman who, uprooted from her original culture and language, had to be “born again” in a new language and in a new place (Palestine). She compared the process of becoming a Hebrew speaker as an adult to going back to infancy and learning the language as a child, and felt that at the age of 34, her Hebrew competence was that of a 10-year-old child.79

How does analyzing the age of Olam Katan’s readers relate to changes in Jewish life at the beginning of the 20th century? First, the data on the different age groups among Olam Katan’s readership demonstrate that although some readers received a form of modern education, when it came to defining who was “a child” and who was “a young person,” their upbringing was still rooted in the traditional system. Ben-Avigdor and Gordon recognized the need to differentiate between children and teenagers and responded with a separate press title for each of these groups. Paradoxically, this acknowledged not only the traditional Jewish paradigm of coming-of-age, but also modern differentiation between children and teenagers and sensitivity to their needs as consumers of Hebrew culture. Additionally, factors such as class, social, and household financial standing defined Jewish childhood as much as the factor of biological age. For some Jewish children in Eastern Europe, the local political or economic situation terminated their childhood prematurely, pushing them to become “little Jews without beards.”80

CONCLUSION

“I wish to talk in Hebrew through Olam Katan also with my little Zionist friends in other cities,” wrote Shlomo Ben-Avraham in his letter to the periodical in 1903.81 The first illustrated Hebrew children’s journal offered Zionist children from different Jewish communities exactly such a means of communication. Spatial analysis of Olam Katan’s readership proved that in studying this communication, two factors need to be equally taken into consideration: the trans-geographical character of early Zionist children’s culture and the specific geo-political context which defined both the functioning of the periodical and the lives of its readers.82 Crossing the geo-political borders of the states in which Jews lived, Olam Katan functioned within the traditional trans-geographical network of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe—but it also had the scope of distribution characteristic of modern mass media. Additionally, studying local political and cultural contexts helps to explain more complex dynamics of the periodical’s geography and readership.

The question of Hebrew education and gender points to the existence of a peculiar but widespread phenomenon: although many aspects of Jewish life changed over the course of the 19th century in Eastern Europe, new and revised forms of education did not really eradicate centuries-long educational patterns, which continued to function alongside the modern forms. The traditional Jewish concepts of childhood and adulthood, which had specific religious, cultural, and social implication, converged in Olam Katan’s readership with modern ideas of childhood and the need to differentiate between young people of various ages. This, together with the issue of geography and gender, demonstrates that Jewish childhood in Eastern Europe was defined by a more complex paradigm of modernization than in the better studied cases of Central and Western European Jewish communities.

Eastern European modernity offered alternatives to the previous model(s) of Jewish life, but did not erase them. This split, which created multiple versions of Jewish culture and which led to the fragmentation of Jewish identity, is one of the most intriguing characteristics of Jewish modernity in Eastern Europe. This fragmentation did not only affect Jewish adults, it also influenced children. The childhood of Zionist children, discussed in this article, was only one of many possible Jewish childhoods. Alongside it, other patterns functioned and developed, offering different role models for children and defining children’s experiences and practices differently.83

Letters sent by children to Olam Katan offer insight into the making of this modern Zionist childhood. They document Zionist culture as a work-in-progress, a project being created at the grassroots level. They demonstrate the popularization of Hebrew at a time when Hebrew language was still in its pre-vernacular phase. Thanks to them, we can identify practices, experiences, and symbols of Zionist childhood in Eastern Europe and beyond. The “modernity” of this childhood was a complex and ambiguous category which drew equally on the new and the old.

This study’s analysis of press published for children and the children’s letters contained within is far from being complete and there are many possible avenues for further research. First, there is more work that can be done to further reconstruct the life stories of these children. At present, we only know who they became later in their lives in some selected cases. Itsḥak Landoberg, who as a 12th-year-old boy wrote a letter about peace and the coming of the Messiah, later emigrated to Palestine, changed his last name to Sade, and eventually became known as a commander of the Palmach and one of initiators of the Israeli Defense Forces.84 The adult Aaronsohn siblings, Rivka, Sara, and Alexander, established an espionage organization, Nili, which spied in the Ottoman Empire for the British Empire.85 However, successfully identifying Olam Katan’s readers is a challenging task, as some of them made aliya to Eretz Yisrael and changed their family names (like Landoberg/Sade). Those who stayed in Europe had to face two world wars and the Holocaust, which ultimately destroyed Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.86

The second direction for further research is to continue developing the spatial analysis by comparing a map of active Zionist children presented in this article with a map of adult Zionist activism. It may answer the question of whether children’s and adults’ Zionist activism overlapped geographically or not, and if or how adult Zionist practices influenced children’s practices. After all, writing letters to the press was an adult practice that children emulated and exercised in their press. My reading of children’s correspondence shows that there were other adult activities (like fundraising or establishing agudot, Zionist associations) which were mirrored by children. However, Zionist children’s culture also developed activities designed for children only (plays, games, songs, etc.). Comparing Zionist activities in big cities and in small towns could also offer an interesting perspective.

The third direction is to incorporate the notes left by readers of Olam Katan on pages of their periodical into the study of children’s ego-documents. These were hand-written comments responding to the texts in the periodical, attempts to solve puzzles and crosswords, or various drawings and doodles. Such paratexts offer intimate and direct contact with the reader’s experience, not mediated by editors nor anyone else. Those who, like me, might want to recreate a science experiment described some 120 years ago in Olam Katan can read a hand-written warning in Hebrew next to the text: “I have tried this experiment but it didn’t work.”87

I would like to thank Agnieszka Cieślik, Magdalena Krzyżanowska, Leszek Kwiatkowski, Vladimir Levin, Ekaterina Oleshkevich, Shaul Stampfer, and my colleagues from the Taube Department of Jewish Studies at the University of Wrocław, with whom I consulted during my research and/or drafting an earlier version of this paper. I am grateful to Waldemar Spallek, who translated my research into cartography and offered many valuable comments in the process. Anna Piątek, Dror Segev, Shaul Stampfer, and Magda Sara Szwabowicz assisted me in accessing necessary research materials. I am also grateful to Avigail Oren for proofreading this article. The publication is partly financed by funding from the “Initiative of Excellence—Research University” program and from the Centre for Research on Children’s and Young Adult Literature at the University of Wrocław.

Footnotes

Studies of readers of the pre-war Jewish press in Eastern Europe mostly focus on subscribers. See Vladimir Levin, “Zur Verbreitung jüdischer Zeitschriften in Rußland: Sprache versus Geographie,” in Die jüdische Presse im europäischen Kontext, 1686–1990, edited by Susanne Marten-Finnis and Markus Winkler (Bremen, 2006), pp. 101–119; Anatolii Khaesh, “Podpischiki almanakha ‘Evreyskaya starina’ (1909–1912 gg.),” Evreyskaya starina, Vol. 3 (2013), pp. 188–238, also available at https://berkovich-zametki.com/2013/Starina/Nomer3/Haesh1.php (accessed 28 April 2024).

This periodical should not be confused with other Hebrew children’s journals bearing similar titles, like Olam Katon (published in Jerusalem in 1893), nor with Olami, Olami Ha-katan, or Olami Ha-ketantan (all published in the 1930s in Warsaw).

I use the term in the sense of the re-vernacularization of the Hebrew language. On the criticism of the concept of “Hebrew revival,” see Sonya Yampolskaya, “Internationalisms in the Hebrew Press 1860s–1910s as a Means of Language Modernization,” in From Ancient Manuscripts to Modern Dictionaries: Select Studies in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek, edited Tarsee Li, Keith Dyer (New York, 2017), pp. 312–313.

On the role of children in the process of the re-vernacularization of Hebrew, see Basmat Even-Zohar, “Shituf ha-yeladim ba-yozma ha-ivrit ba-shanim 1880–1905,” Dor le-dor, vol. 36: Yeladim be-rosh ha-maḥane: yaldut u-neurim be-itot mashber u-temura (2010), pp. 39–69; Yael Reshef, “The role of children in the revival of Hebrew,” in No Small Matter: Features of Jewish Childhood, edited by Anat Helman (New York, 2021), pp. 20–38. On children in the process of constructing a national Hebrew culture in the later period of the Yishuv (the Jewish settlement in Palestine) and in Israel, see Yael Darr, The Nation and the Child: Nation Building in Hebrew Children’s Literature, 1930–1970 (Amsterdam, 2018).

For more on Ben-Avigdor’s efforts to raise Hebrew readers, see Agnieszka Jagodzińska, “How to Create a Hebrew Reader? Olam Katan (1901–1904) and the Young Hebrew Reading Public,” Children’s Literature in Education (online first 2022) vol. 55 (2024), pp. 501–516, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-022-09520-w (accessed 23 March 2024).

David Assaf, Yael Darr, “What Kind of Self Can a Pupil’s Letter Reveal? The Tarbut School in Nowy Dwór, 1934–1935,” Polin, Vol. 36: Jewish Childhood in Eastern Europe (2024), p. 182.

Some of these challenges and questions are discussed in: ibid., pp. 183–184. See also Meirav Reuveny, “Our Small World: Hebrew Children’s Letters and Modern Upbringing in Czarist Russia,” Jewish History, Vol. 37 (2023), pp. 262–263, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10835-023-09454-w (accessed 23 April 2024).

Gershon David Hundert, “Re(de)fining Modernity in Jewish History,” in Rethinking European Jewish History, edited by Jeremy Cohen, Moshe Rosman (Portland, Oregon, 2009), pp. 133–145.

Ekaterina Oleshkevich, History, Culture, and the Experience of Jewish Childhood in Late Imperial Russia (PhD thesis, University of Bar-Ilan, 2023), pp. 324–328 (quotation p. 328).

The total number of issues of Olam Katan was 175. However, 20 of the 175 were released as double issues, meaning that upon 10 occasions readers received a double-numbered edition (e.g. 1902 Nos. 2–3) with an extended number of pages. So, the number of printed paper issues was actually 155, and I use this figure as the denominator to calculate the percentage of issues containing readers’ correspondence.

In the first year of publication (1901–1902), 48 out of 64 issues (75 percent) contained letters from readers; 30 out 44 issues (68 percent) did so in the second year (1902–1903); and 23 out of 41 issues (56 percent) did in the third year (1903–1904); while in the last year (1904), during which only 6 issues were published, only 3 out 6 (50 percent) printed readers’ correspondence.

These numbers refer to the total number of letters, including multiple letters sent by the same writer.

For this last observation, I thank Vladimir Levin.

This is hinted at by sections in the periodical in which editors announced the names of children who solved puzzles or who sent donations. It is only natural to assume that these solutions and donations came in a letter.

See, for example, Menahem Regev “Mori amar li ki alenu, ha-yeladim, leehov et sefatenu (mikhtevei yeladim le-Olam Katan),” Sifrut yeladim ve-noar, Vol. 32 No. 2 (2005), p. 42.

The first attempt to analyze these letters was made in M. Regev “Mori amar li ki alenu…,” pp. 38–46. The newest study by Meirav Reuveny offers a comparative analysis of children’s letters in Olam Katan and in three other Hebrew periodicals for the young audience published in Eastern Europe, see M. Reuveny, “Our Small World.”

This section seemed to lose significance over time, even more than was the case with readers’ correspondence. Additionally, the editors only printed the names of children who solved the puzzle, together with their place of origin, in the first half of the first year of Olam Katan’s publication. Later, after issue 29 in 1902 (with two random exceptions in 1904), only the children’s names were published, without including the names of their towns or cities.

Hebrew children’s literature more generally also began under the same conditions, with “no natural reading public.” See Zohar Shavit, “Hebrew and Israeli Children’s Literature,” in International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature, edited by Peter Hunt (London, 1996), p. 788.

See Agnieszka Jagodzińska, “Cromwell in the Shtetl: Translations of Non-Jewish Literature in Early Hebrew Periodicals for Children,” Studia Judaica, Vol. 51, No. 1 (2023), pp. 69–94. For more on the role of translated literature in the development of Hebrew literature, see Zohar Shavit, “The Status of Translated Literature in the Creation of Hebrew Literature in Pre-State Israel (the Yishuv Period),” Meta, Vol. 43, No. 1 (1998), pp. 1–8, https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/004128ar (accessed 25 July 2022). On translated literature versus the original literature in Hebrew, see Zohar and Yaacov Shavit, “Lemale et ha-aretz sefarim. Sifrut mekorit leumat sifrut meturgemet be-tahalikh yetsirato shel ha-merkaz ha-sifruti be-Eretz Yisrael,” Ha-sifrut, Vol. 25 (1977), p. 45–68.

Gordon stayed in Palestine between 1898 and 1901 and ultimately settled there in 1924, but during the years of Olam Katan’s publication he lived in Warsaw. See entry “Gordon, Shmuel Leib,” in Uriel Ofek, Leksikon Ofek le-sifrut yeladim, Vol. 1 (Tel Aviv, 1985), p. 152.

Places in this article are named according to the following rules: Polish versions of place names are used for all the localities in the Kingdom of Poland; Russian versions are used for the Pale of Settlement and Russia; Hungarian for the Kingdom of Hungary, and Romanian for Romania and Bukovina. I made an exception for big cities with recognizable English names, for example, Warsaw and not Warszawa. For places whose historical and contemporary name variants are completely different, I provide the contemporary name, for example, Mitava (Jelgava). Palestine and Eretz Yisrael are used in reference to the same geographical territory, but their use depends on the context. My choice of geographical names in this article is by no means intended to convey ideological, political, or imperial messages.

It is important to note that sometimes children sent their letters from their vacation destinations and not from their actual place of residence. See, for example: Olam Katan [further abbreviated to OK in the endnotes], Vol. 1, No. 61 (1902), col. 358; Nos. 1–2 (1903), col. 21.

Luaḥ ha-zikaron li-shenat yovel ha-ḥamishi shel Ha-Tsefira (Varsha, 1912), pages unnumbered [24–27]. I thank Vladimir Levin for sharing this source with me.

V. Levin, “Zur Verbreitung jüdischer Zeitschriften in Rußland,” p. 118.

In fact, correspondence in Olam Katan demonstrates that some readers already had sufficient Hebrew knowledge and were reading the regular (adult) press in Hebrew, like Ha-Tsofe or Ha-Zeman (see OK Vol. 3, No. 21 (1904), col. 491).

I found no records concerning Ben-Avigdor’s possible attempt to secure permission to publish Olam Katan in Warsaw, neither in Ben-Avigdor’s archive in the Machon Genazim (IL-GNZM-157-2) nor in the Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw (AGAD). In the latter archive, there is only a file on Ben-Avigdor’s later request (from 1910) for permission to publish a “weekly journal in ancient Hebrew” titled Biblioteka Ketana [A small library]. The permission for publication was granted in 1911 (AGAD, KGGW, 1439, folios 1–13). We know that in 1910 Ben-Avigdor started to publish a serial (mostly weekly) literary publication, but it was titled Biblioteka Gedola [A grand library]. See Bernard Jakubowicz, Asot va-ḥafets sefarim harbe. Le-toldoteha shel hotsaat ha-sefarim “Tsentral”-“Merkaz” be-Varsha (1911–1933) (MA thesis, Tel Aviv University, 1997), p. 75; Magda Sara Szwabowicz, Hebrajskie życie literackie w międzywojennej Polsce (Warszawa, 2019), p. 54. The circumstances of the possible title change of this publication and the question of licences for the publication of Ben-Avigdor’s other periodicals remain unclear.

Zenon Kmiecik, Prasa warszawska w latach 1886–1904 (Wrocław, 1989), p. 18.

Olam Katan was not the only publication that Ben-Avigdor published outside the Kingdom of Poland. Other Tushiya periodicals—Ha-Neurim, Ha-Pedagog, and Di Yudishe Froyenvelt—were also published in Cracow.

The map shows all the train routes that existed in this territory in 1902. The sources used for reconstructing this railway network are: E[duard] Y[ulyevich] Petri, Uchebnyj geograficheskiy atlas. 48 glavnykh kart, 137 dopolnitelnykh i chertezhey na 47 tablitsakh, third edition, S[ankt]-Peterburg 1901; database Historia kolei na ziemiach polskich. Ogólny rys historyczny, https://www.pod-semaforkiem.aplus.pl/hi_1800.php (accessed 7 March 2024); W[ilhelm] Koch, C[arl] Opitz, Eisenbahn- und Verkehrs-Atlas von Europa, Leipzig 1912; Karta zheleznikh, shossieynikh i vnutrennikh wodnikh putiey soobshchenia, 1893; Entsiklopedicheskiy slovar, [edited by K. K. Arsenyev and F. F. Petrushevsky], publ. F[riedrich] A[rnold] Brockhaus, I[lyia] A[bramovich] Efron, Vol. 27a (Sankt-Peterburg 1899), p. 457, https://viewer.rsl.ru/ru/rsl01003924206?page=457&rotate=0&theme=white (accessed 7 March 2024).

For more on the logistics and financial aspect of publication of Olam Katan, see A. Jagodzińska, “How to Create a Hebrew Reader?” pp. 506–508.

Locations given in solutions to riddles were excluded from these statistics, as the variable in the database for Map 2 was one letter sent from each place, no matter how many children signed it. The way in which the section with solutions to riddles was organized suggests that the variable in this case was one person and not one letter which does not offer a common denominator with the database of the letters.

The train stations closest to Lutsin were Rzeżyca or Mežvidi (today both ca. 25 km distance).

For a description of Zionist initiatives in Lutsin (Ludza), see “Ludza” - Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Latvia and Estonia (Ludza, Latvia), English translation by Jerrold Landau of Pinkas Ha-kehilot Latvia ve-Estonia, ed. Dov Levin (Jerusalem, 1988), pp. 160–167 at see https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_latvia/lat_00160.html (accessed 14 March 2024). It is possible that the outstanding Hebrew teacher known by the name of Yechiel Shuval (former surname Shavlov), whose activity in 1930 is mentioned the above pinkas, was the “Yechiel Shevel” who wrote a letter to Olam Katan as a child in 1904, identifying himself as a head of the “Pirḥei Tsiyon” association in Lutsin (OK, Vol. 3, Nos. 42–42 (1904), cols. 1000–1001).

In 1901, a Hebrew school opened in Dvinsk (with Hebrew as the language of instruction) and was attended by 81 pupils. As one of the Dvinsk Jews, Mordechai Nieshtet, put it: “Zionism was not so much an ideology for us, but rather simply a part of our character, something we drank in with our mother’s milk; we absorbed it in the home and the cheder, at school and in the atmosphere on the street, from visiting teachers and emissaries from Eretz Yisrael, and in the libraries.” See In Memory of the Community of Dvinsk (Daugavpils, Latvia), English translation by Amy Samin of Le-zekher kehilat Dvinsk (Haifa, 1975), pp. 13, 24 (quotation p. 24): https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/Daugavpils/Daugavpils.html (accessed 14 March 2024).

Yehuda Slutsky, entry “Goldberg, Isaac Leib,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/goldberg-isaac-leib (accessed 12 March 2024).

See Ezra Mendelsohn, On Modern Jewish Politics (New York, 1993), pp. 40–44. On spaces of Jewish Lite—see Darius Staliūnas (ed.), Spatial concepts of Lithuania in the long nineteenth century (Brighton, 2016).

Ekaterina Oleshkevich points to a significant difference in the number of Jewish autobiographies in Jewish Lite and in the territory of Ukraine. See E. Oleshkevich, History, Culture, and the Experience of Jewish Childhood in Late Imperial Russia, pp. 13–14.

See, for example, OK, Vol. 1, No. 48 (1902), col. 365. Some of these expectations are also echoed in the correspondence from children living in Nowy Dwór and writing about Eretz Israel in the later period (1934–1935). See Assaf Darr, “What Kind of Self Can a Pupil’s Letter Reveal?” p. 192.

OK, Vol. 3, Nos. 2–3 (1903), col. 59. A similar story, also from Odessa, is reported in OK, Vol. 1, No. 29 (1901), col. 118.

Meirav Reuveni has discussed the question of gender in four children’s periodicals in Hebrew (including Olam Katan). See M. Reuveny, “Our Small World,” pp. 273–277. This section offers more in-depth analysis of this problem in Olam Katan.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1901), cols. [3]-6 and cols. [59–60].

OK, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1901), cols. [59–60]. On the knowledge and usage of Hebrew in Eastern Europe, see Shaul Stampfer, “What did ‘knowing Hebrew’ mean in Eastern Europe?” in Hebrew in Ashkenaz: A Language in Exile, edited by Lewis Glinert (New York, 1993), pp. 129–140.

Eliyana R. Adler, In Her Hands: The Education of Jewish Girls in Tsarist Russia (Detroit, 2011), pp. 91–92, 133, 147–148.

E. Oleshkevich, History, Culture, and the Experience…, p. 14.

Moshe Kligsberg, Child and Adolescent Behavior under Stress: An Analytical Topical Guide to a Collection of Autobiographies of Jewish Young Men and Women in Poland (1932–1939) (New York, 1965), p. 10. Printed selections of these autobiographies can be seen, for example, in Alina Cała (ed.), Ostatnie Pokolenie. Autobiografie polskiej młodzieży żydowskiej okresu międzywojennego (Warszawa, 2003) and Jeffrey Chandler (ed.), Awakening lives: Autobiographies of Jewish youth in Poland before the Holocaust (New Haven, 2002).

The calculation is based on Assaf, Darr, “What Kind of Self Can a Pupil’s Letter Reveal?” p. 184.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 27 (1901), col. 38.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 22 (1901) col. [967]-96.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 48 (1902), col. 365. In another letter, the boy’s surname is spelled Biskin (OK, Vol. 2, No. 36 (1903), col. 798).

See, for example, OK, Vol. 1, No. 19 (1901), col. 851.

OK, Vol. 2, No. 32–33 (1903), col. 729.

M. Reuveny, “Our Small World,” p. 276.

Ibid., pp. 273–274.

In original Hebrew: temunot (literally: pictures). The term refers to a popular genre in 19th-century literature.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 62 (1902), col. 397.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 63 (1902).

OK, Vol. 2, Nos. 27–29, 31, 35, 38, 40, 44–47.

OK, Vol. 2, No. 12 (1903).

OK, Vol. 2, Nos. 15–16, 18 (1903).

For example, see OK, Vol. 1, No. 33 (1902), col. 251–254.

E. Oleshkevich, History, Culture, and the Experience…, p. 92.

Ibid., p. 94.

The transcription of the word shevui in the periodical’s subtitle (and not shavui, as in the original) follows the standard Modern Hebrew transcription.

The same rule was applied as in the gender statistics presented above.

In some liberal strains of Judaism, a similar ceremony for girls developed. At the age of 12 or 13, a girl goes through the ceremony of bat mitsva, which initiates her into her life as a Jewish woman.

David Zabludovsky, Fargangene Yorn (Mexico, 1969), pp. 59–60.

A. Jagodzińska “How to Create a Hebrew Reader?” p. 507.

OK, Vol. 2, Nos. 25–26 (1903), col. 565.

OK, Vol. 2, No. 51 (1903), col. 1149.

Ha-Neurim was published between 1903 and 1904 in Cracow.

In Ha-Neurim, vocalisation was used in poetry, which remains a standard use today.

See OK, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1901), cols. [59–60].

OK, Vol. 3, No. 37 (1904), col. 587–588.

OK, Vol. 3, No. 17 (1904), col 381.

On the development of Hebrew children’s literature, see Zohar Shavit, “Hebrew and Israeli Children’s Literature,” in International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature, edited by Peter Hunt (London, 1996), pp. 783–788.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 8 (1901), cols. [387–388].

OK, Vol. 1, No 33 (1902), cols. 285–286.

Although Eliezer Ben-Yehuda was undoubtedly one of the important figures in the process of the re-vernacularization of Hebrew, new studies offer more complex understandings of this process—see, for example, Yael Reshef, “The Re-Emergence of Hebrew as a National Language,” in The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook, edited by Stefan Weninger et al. (Berlin-Boston, 2011) pp. 546–554; Zohar Shavit, “‘Can It Be That Our Dormant Language Has Been Wholly Revived?’: Vision, Propaganda, and Linguistic Reality in the Yishuv Under the British Mandate,” Israel Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2017), pp. 101–138; and Zohar Shavit, “Ma dibru ha-yeladim ha-ivriyim? Al proyekt ha-ivriut u-veniat ḥevra leumit be-Eretz Yisrael,” Israel, No. 29 (2021), pp. 7–30, [VII].

Ḥemda Ben-Yehuda, “Le-toldotai,” OK, Vol. 2, No. 12 (1903), cols. 243–246.

This concept of Shmuel Niger’s is discussed in Natan Cohen, “No More ‘Little Jews Without Beards’: Insights into Yiddish Children’s Literature in Eastern Europe Prior to World War I,” Modern Judaism, Vol. 41, No.1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/mj/kjaa018 (accessed 18 March 2024), p. 93.

OK, Vol. 2, Nos. 15–16 (1903), p. 343.

This approach responds to Moshe Rosman’s criticism of studies that make only one of these two aspects the operational and interpretative category of their analysis: see Moshe Rosman, “Jewish History across Borders,” in Rethinking European Jewish History, edited by Jeremy Cohen and Moshe Rosman (Liverpool, UK, 2009), pp. 15–29. Perhaps the best example of a study that successfully balances these two aspects is Marcin Wodziński, cartography by Waldemar Spallek, Historical Atlas of Hasidism (Oxford, 2018).

E. Oleshkevich writes about the “multiplicity of childhoods.” See E. Oleshkevich, History, Culture, and the Experience…, p. 324.

OK, Vol. 1, No. 35 (1902). Landoberg was identified by M. Regev, “Mori amar li ki alenu…,” pp. 45–46.

See their letter in OK, Vol. 3, No. 28 (1904), col. 651–652. See also: U. Ofek, Sifrut ha-yeladim ha-ivrit…, p. 362.

A source that may be helpful in reconstructing partial information about some of the children in their twenties or thirties is a collection of yizkor books, which record not only the annihilation of Jewish communities in Europe but also their pre-war life.

OK, Vol. 1, 1901, No. 21, col. 924. This copy is from the collection of the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem.