Newslore: Contemporary Folklore on the Internet

Newslore: Contemporary Folklore on the Internet

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

“It Raised My Spirits so I’M Passing it On” “It Raised My Spirits so I’M Passing it On”

-

When the Going Gets Tough, The Tough Go Photoshopping When the Going Gets Tough, The Tough Go Photoshopping

-

“This One Will Make You Cringe” “This One Will Make You Cringe”

-

Vengeance Vengeance

-

Nothing Sacred Nothing Sacred

-

Unfit to Print Unfit to Print

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

3 When the Going Gets Tough: Newslore of September 11 Purchased

-

Published:April 2011

Cite

Abstract

This chapter examines the newslore about the September 11, 2011 terrorist attack against the U.S. It explains that this event triggered the largest folk responses in the short history of computer-mediated communication, but there were no joking about the victims. Most of the jokes were only defiant gestures that were considered by virtue of their clever vulgarity. This chapter also discusses the influence of the U.S. government’s declaration of the war on terror in providing a focal point for American anger and fantasies of revenge and in making the “enemy” the focus of the September 11-related jokes.

“It Raised My Spirits so I’M Passing it On”

A premise of this book is that we can learn more about how “ordinary Americans” respond to national and world affairs from the mass e-mails they exchange than we can from the news media. In this chapter, I would like to illustrate this point via a chronological look at the e-mails I received in the days and week following the suicide attacks of September 11, 2001. The e-mails suggest that after a brief period of stunned and perhaps respectful silence in the aftermath of the attacks, cybercitizens resumed joking. Most of the jokes played it safe by targeting the Muslim world in general and Osama bin Laden in particular. While some of these jokes were straightforward fantasies of by-the-sword revenge, in the darkest ones, not even obliteration was enough: bin Laden needed to be scatologically and sexually humiliated. The jokes’ subversiveness, then, lay not in the challenge they posed to the Bush administration’s response to the attacks—if anything, the jokes suggested that a substantial number of citizens supported a military response—but in the challenge they posed to the dispassionate language of the news reports. The hegemony of journalism’s objective tradition has been challenged precisely on the grounds that the affectless tone of news reports gives the public the impression that reporters and the news organizations they work for are disengaged from the communities they cover.

The first e-mail I received on September 11 was a forwarded “MESSAGE FROM DR. SPANIER” from the dean of my college. Penn State president Graham Spanier’s message to the faculty urged us to “stand together and do our utmost to provide mutual support and comfort” to meet with our classes as scheduled, to report “safety-related concerns” and to apprise our students of the counseling services available to them. I also received a message from a colleague who knew I grew up in New York and wanted to know if I was “OK.”

Then came the mass e-mails, most of which were forwarded to me by my mother. The first of them came with the subject line “Fwd: [Fwd: FW: TRIBUTE TO AMERICA],” the three “forwards” providing the first indication of how widely distributed the messages were. I was one of twenty people who received my mother’s forward. (I could see, from the other e-mail addresses, that I was related to at least eight of these people.) But my mother is one of those forwarders who pass a message along as is, without trimming any of the redundancies. So after her group of addressees came the group she was part of, which consisted of another forty-two people. Beneath that group was a third layer of 22 addressees, followed by a fourth set of 15, and a fifth group of 3. That’s 102 people, but there’s no reason to think it either began or ended with the first group or the fifth. If any of these 102 people forwarded in turn to their own set of e-mail correspondents, we can only guess at the exponential growth in the number of recipients. This is what I mean by a mass e-mail.

“Tribute to America,” by the Canadian radio commentator Gordon Sinclair, extolled Americans as “the most generous and possibly the least appreciated people on all the earth.”1Close It included lines that sounded, given the timing, as if they were alluding to the September 11 attacks: “They will come out of this thing with their flag high. And when they do, they are entitled to thumb their nose at the lands that are gloating over their present troubles.” In fact, though, another “Tribute” e-mail forwarded by a friend explained that Sinclair’s commentary was originally broadcast in 1973. Its opening sentence, deleted from the first version I received, made clear what had occasioned it: “The United States dollar took another pounding on German, French, and British exchanges this morning hitting the lowest point ever known in West Germany.” Not terribly earth-shaking compared to 9/11.

In any case, an anonymous link in the long chain of forwarders added the following peevish postscript:

This is one of the best editorials that I have ever read regarding the United States. It is nice that one man realizes it. I only wish that the rest of the world would realize it. We are always blamed for everything and never even get a thank you for the things we do.

I would hope that each of you would send this to as many people as you can and emphasize that they should send it to as many of their friends until this letter is sent to every person on the web. I am just a single American that has read this.

One of the e-mails I received ended there. The other continued, “I am just a single American who has read this, but I SURE HOPE THAT A LOT MORE READ IT SOON,” which suggests that this tag end was inadvertently cut off the other version.

The second mass e-mail I received from my mother on September 13 was essentially a condolence card to America from the assistant manager of a hotel in Baja California. “This note I’ve forwarded can be viewed as a clever marketing tool,” a forwarder named Karen wrote. “I choose, however, to feel warmed, moved and refreshed by the thoughts shared here.”

My mother received the next mass e-mail from my sister, who commented, “This one’s intense!” The message, authored by a Floridian named Charles Bennett, was a paean to America’s freedom and Americans’ spirit. The accompanying note, from someone preceding my sister in the chain:

i received this early this morning……..it raised my spirits a bit so i’m

passing it on.

xoxo

jo-anne

The Bennett piece bore some resemblance to one written by Leonard Pitts in his popular 9/11 column. Here are the last lines of Bennett’s essay: “Wait until you see what we do with that Spirit, this time. Sleep tight, if you can. We’re coming.” And here is how Pitts’s column ends: “You don’t know my people. You don’t know what we’re capable of. You don’t know what you just started. But you’re about to learn.”2Close If the twenty-six-thousand e-mails Pitts received in response to the column are any indication, the column reflected a widespread thirst for vengeance that provided political cover for the Bush administration’s subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

The next day, September 14, I received a rather more scholarly forward from my wife with the subject line “Sources of Terrorism Against the US.” Attributed to Steve Niva, a professor of international politics and Middle East studies at Evergreen State College—I verified that Niva is, in fact, on the faculty at Evergreen State—the message outlines, at considerable length, some of the causes of Islamist anger at the United States while stressing that “there is no justification for the horrendous attacks on innocent American civilians in New York or Washington.” Commented one of the forwarders: “I thought this analysis of US policies and Middle East politics might be useful to members of the Family Medicine and Community Health list. I know I need all the information I can get about this situation.”

The same day as the Niva essay landed in my in-box, I received what my sister labeled “Another weird one!” before she passed it on to my mother. Here is that e-mail in its entirety:

for those of you who are not familiar with this, within Jewish mysticism is the study of numerology, the letters all have number values, though i don’t know what the significance of all this is, i have to admit that it piques my curiosity.

i remember years ago, when israel was being attacked by scud missiles, we received a letter from a girl from israel, who showed us the numbers of the “patriot” missiles and that they had the same number value of “shomer”, which means watchman, and is one of the hebrew names for god. this may mean nothing to you, and i am not suggesting that it should, enjoy it for what it is worth, and delete it if it seems meaningless to you. always wondering,

jo-anne

The date of the attack: 9/11 -9 + 1 + 1 = 11

September 11th is the 254th day of the year: 2 + 5 + 4 = 11

After September 11th there are 111 days left to the end of the year.

119 is the area code to Iraq/Iran. 1 + 1 + 9 = 11

Twin Towers - standing side by side, looks like the number 11

The first plane to hit the towers was Flight 11

I Have More…….

State of New York - The 11 State added to the Union

New York City -11 Letters

Afghanistan -11 Letters

The Pentagon -11 Letters

Ramzi Yousef -11 Letters (convicted of orchestrating the attack on the WTC in 1993)

Flight 11 - 92 on board - 9 + 2 = 11

Flight 77 - 65 on board - 6 + 5 = 11

The date of the attack: 9/11 -9 + 1 + 1 = 11

September 11th is the 254th day of the year: 2 + 5 + 4 = 11

After September 11th there are 111 days left to the end of the year.

119 is the area code to Iraq/Iran. 1 + 1 + 9 = 11

Twin Towers - standing side by side, looks like the number 11

The first plane to hit the towers was Flight 11

A mass e-mail that arrived on September 16 exhorted the receiver to “keep the message going,” though unlike other chain e-mails, it threatens no consequences as a result of not doing so:

We are keeping this candle burning for all the people & their families who were in the planes, buildings and anywhere near the explosions today. May God be with them and help them through this terrible time.

God Bless

Keep The Candle Going

I asked God for water, he gave me an ocean.I asked God for a flower, he gave me a garden.I asked God for a tree, he gave me a forest.I asked God for a friend, he gave me YOU.“There is not enough darkness in the world to put out the light of one candle.”

The Candle of Love, Hope and Friendship

This candle was lit on the 11th of September, 2001. Someone who loves you has helped keep it alive by sending it to you.

Don’t let The Candle Of Love, Hope and Friendship die!

“A candle loses nothing by lighting another candle”

What can this partial collection of mass e-mails from the first week after the attacks tell us? In contrast to the brevity and frivolity typical of so much computer-mediated communication, all the material shared in the immediate aftermath of September 11 was serious, and much of it was remarkably long. People were angry, sad, and bewildered, and they were willing to read whatever best expressed those states of mind. Even Dan Kurtzman, the steward of the vast About.com humor Web site, posted the following message to regular visitors on September 13:

In light of recent events, there will be no new humor material posted to this site this week.

Eventually, laughter will have an important role to play in helping heal our national psyche, but now is clearly not the time.

For the latest news and commentary, I recommend you check out About.com’s special coverage of America under attack, as well as some of the other useful links and resources listed on this page.

If you would like to be notified when About Political Humor returns with new material, feel free to sign up for my newsletter and I’ll drop you a line.

My heart goes out to all those who perished in this terrible tragedy and to all those mourning the loss of loved ones.

The revival of Sinclair’s Canadian tribute and the condolence message from Baja suggest a need for reassurance, after being stunned by Islamist hatred, that not everyone hates us. The Bennett piece gives voice to America’s anger and thirst for vengeance, while Professor Niva’s remarks counsel a more temperate response. If Bennett represents the hawkish and perhaps conservative response to September 11, and Niva the dovish and possibly liberal response, together they tell us that the world of computer-mediated communication is the domain of neither the political right nor the political left.

If this small sampling is representative of the totality of what was swirling around cyberspace from September 11 to 17, the numerological analysis and the chain candle would indicate a shift from positivistic to mystical responses. After all the tough talk and calls to action, it may have begun to sink in that there wasn’t much we civilians could do about what had happened. And as the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski pointed out in his landmark study of magic in the Trobriand Islands in the 1920s, when rational explanations and behaviors are less than satisfying, we become receptive to less rational approaches.4Close Numerology assures us that there is an internal logic to events that on the surface seem inexplicable. In the absence of the comfort of action, the candle chain offers the comfort of virtual communion, which is the comfort of e-mailing itself.

But then, on September 18, it was as if a barrier had been lifted: It became okay to joke and to spread stories of dubious veracity.

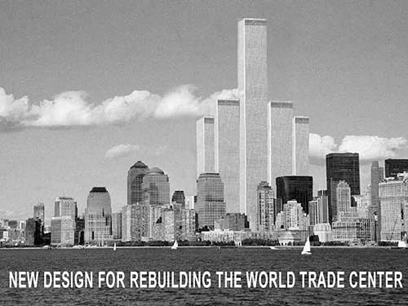

When the Going Gets Tough, The Tough Go Photoshopping

The first September 11 joke I received, one week after the attacks,5Close was a visual one: a digitally altered photographic design for a new World Trade Center with five towers, the middle one taller than the rest.6Close To build an even more imposing structure on the site of the towers would already be an act of defiance. To build it in the shape of the digitus impudicus is to give symbolic form to that act of defiance. The folklorists Joseph Goodwin and Bill Ellis both suggested that America suffered a symbolic castration when the Twin Towers were toppled.7Close “The finger” would signal a return to potency. On another level, the digitus impudicus is simply a gesture of impotent rage: it’s about all a driver can do to express his displeasure with another motorist who has cut him off—although it could be argued that even here the expression “to cut someone off” suggests that to be thwarted in one’s forward automotive progress is to suffer a symbolic castration.

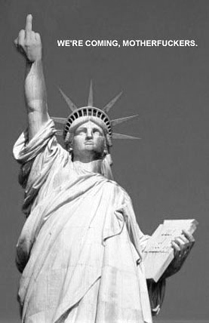

The other photoshopped image I received on this theme (on September 29) substituted the finger for Lady Liberty’s torch. In keeping with the folk penchant for recycling images and motifs,8Close Lady Liberty’s obscene gesture recalls folk cartoons of Mickey Mouse making the same gesture in response to Iranian students’ seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979.9Close The cartoon, photocopied and faxed, expressed the feeling that after Vietnam, America had become too innocent, too cuddly, and so risk-averse that we gave our enemies the impression that if they hit us, we would not hit back. (One argument for keeping our troops in Iraq after Saddam Hussein had been overthrown was that the Iraqi insurgents were counting on Americans to weary of war before the country had been stabilized.) The cartoon said, in effect, hey, don’t underestimate us. Mickey gave way to Lady Liberty, perhaps because the Statue of Liberty appeared in some of the New York harbor photos and video footage of the World Trade Center site and is as much a New York symbol as it is an American symbol. As Dundes and Pagter say, “Stressful and traumatic events of national or international scope often stimulate the generation of new folklore—although the new folklore may turn out to be old folklore in disguise.”10Close

Within days of the September 11 attacks, photoshoppers began circulating their design suggestions for a new World Trade Center.

Returning to our chronology, on September 20 I received a warning from my brother-in-law about the Klingerman virus, an item that I had already received from my mother back on February 10, 2001, but which seemed to take on new life after September 11 amid speculation that the terrorists might follow up with biological or chemical attacks. (The anthrax mailings did not happen until October.) To a student of urban legends, much about this e-mail was immediately familiar. There was a disclaimer from a sender who felt compelled to express some skepticism lest any of his or her addressees think him a fool for believing such obvious nonsense: “Could be a scam but anything is possible, as we all know.” The subtext seems to be that the idea of terrorists using American passenger planes as missiles to attack American buildings would also have seemed farfetched before September 11. There was the acknowledgment that people might dismiss this as another wacko e-mail if one did not slap on a “WARNING” label—in capital letters—and exhort the recipient to “PLEASE READ” and “PLEASE FORWARD TO ALL YOU KNOW.”

Subject: Warning - Do Not Open Blue Envelopes in your U.S. Mail ONCE YOU HAVE READ THIS PLEASE FORWARD TO ALL YOU KNOW.

This is from Schwab corporate headquarters—so it’s no joke. Very scary.

Be careful Just when you thought you were safe, now we have the following to deal with … please read, it definitely is a serious threat to our lives and health. This is an alert about a virus in the original sense of the word … one that affects your body, not your hard drive.

This much-recopied piece of photocopier-and-fax-machine lore circulated after Iranian militants stormed the U.S. Embassy in 1979 and held seventy Americans hostage for 444 days.

A lot of the photocopier lore from the Iranian hostage crisis reappeared during Operation Desert Storm in Iraq in 1991 and again—in updated digital form—in response to the September 11 attacks.

The body of the message goes on to warn that blue envelopes labeled “A Gift from the Klingerman Foundation” contain sponges laced with “a strain of virus they have not previously encountered.” Journalistic verisimilitude is attempted via a quote attributed to “Florida police sergeant Stetson,” though a journalist would look askance at the lack of a first name, the lack of a specific reference to a city police force or the state police, and that name Stetson, which would be a good choice for a southern lawman in a work of fiction. The other interesting thing about the Klingerman virus warning is that, as the “please read” preamble suggests, it restores the literal meeting of virus in a realm that has been dominated by figurative use of the word “virus” to refer to “contagious” computer problems and “viral” to refer to the computer-to-computer spread of the material in this book. If your computer can catch an electronic virus by opening an e-mail, it makes sense that your body can catch a biological virus by opening a piece of snail mail.11Close

Another wave of warning e-mails arrived in mid-October, timed to connect September 11 to Halloween. I received the first on October 11 from a student who had been in a class where we had talked, among other things, about urban legends. The message begins thus: “What you are about to read is a letter that was forwarded to me by a close and honest friend.” And here is how the letter begins: “My friend’s friend was dating a guy from Afghanistan up until a month ago.” The letter explains that the Afghan boyfriend “stood up” the friends friend. When she went to his apartment to confront him, she found that he had cleared out. Then she got a letter from him in which he said he could not explain why but “BEGGED her not to get on any commercial airlines on 9/11 AND TO NOT GO TO ANY MALLS ON HALLOWEEN.” The letter concludes with the writer attesting to the warnings authenticity:

This is not an email that I’ve received and decided to pass on. This came from a phone conversation with a long-time friend of mine last night.

I may be wrong, and I hope I am. However, with one of his warnings being correct and devastating, I’m not willing to take the chance on the second and wanted to make sure that people I cared about had the same information that I did.

A second version, also passed along by a student, was attributed to “a friend of someone I work with.” This is a less detailed version, and it ends thus: “I just heard this tonight, and the source in the company here is pretty credible (one of the partners), so I thought I’d pass the word of caution on to all of you about Halloween, just in case there’s any truth to it.”

Yet another of my students wrote his own introduction to a third version:

Dear Professor Frank,

I received the following email from a friend a week or so ago. I found it interesting at first because it wasn’t sent as a “FWD: fwd: fwd: FWD: Read This!!!: Fwd: Possible terrorist attack on Halloween” but written as if he knew the girl personally. I checked up on it, and two of my roommates had received the exact same email, except as a “FWD: fwd:….” message. I don’t know if you’ve already seen this message floating around or not, but I thought you might find it intriguing. In the wake of September 11th, such “warnings” seem inevitable, given our discussions on Urban Legends. When I asked one of my roommates what he thought about the “Halloween email,” he replied “I guess there’s no shopping for me on October 31st.” When further questioned, he admitted he didn’t really believe the email was true, but he’d rather be safe then sorry. He admitted he doesn’t shop all that much anyway, so staying in wouldn’t be too much of a problem.

Here is the text of his version:

The last thing I want to do is scare you guys but last night one of my friends was telling me that her friend’s bf was from the middle east and dissapeared on Sept 8th. He left her a note telling her to stay away from planes on the 11th and not to go to the malls on Halloween.

Just for my sake please be careful on halloween and use your judgement. I can’t be sure this is completely true but I care about you guys so I’d prefer you stayed away from shopping on halloween. Buy your things a day or 2 early instead.

I hope that this is all a big lie but i just wanted you to be safe.

About.com’s Netlore Archive offered a version that began with a quintessential urban legend disclaimer:

Hi All—

I think you all know that I don’t send out hoaxes and don’t do the reactionary thing and send out anything that crosses my path. This one, however, is a friend of a friend and I’ve given it enough credibility in my mind that I’m writing it up and sending it out to all of you.

Readers unfamiliar with the strange world of urban legends will readily see from this sampling why folklorists sometimes refer to these stories as “foaflore”—short for friend-of-a-friend lore. The warnings to avoid malls on Halloween may have been a response to speculation that the terrorists might next strike in the American heartland to further demoralize Americans with the message that no place is safe. (I remember hearing a loud, low-flying plane while raking leaves on a football Saturday that fall and becoming convinced that it was going to crash into Penn State’s Beaver Stadium, where it could potentially kill many more people than were lost in the World Trade Center attacks.) The warnings also bear an interesting relation to politicians’ exhorting Americans to defeat the terrorists by going about their business—including the business of shopping. “Go to restaurants,” said New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani. “Go shopping. Do things. Show that you’re not afraid. Show confidence in yourself and the city.”14Close

The shopping mall warnings also partake of a larger tradition of Halloween legends, from warnings about pins or razor blades in Halloween treats to rumors that circulate on college campuses from time to time that a costumed psychopath is planning to kill dorm residents on Halloween.15Close (In some versions, a psychic reveals this plot to Oprah Winfrey, who has become a category of urban legend in her own right. Supposedly she booted the fashion designer Tommy Hilfiger [or Liz Claiborne] off her show when he confirmed rumors that he never intended for blacks to buy his clothes. Calls for a boycott ensued.)16Close

In a variation on the mall warning story sometimes referred to as “The Grateful Terrorist,” an Arab warns someone who has done him a favor (like chipping in a small amount of money for his groceries when she learned he was short of cash) not to drink Coke or Pepsi after a certain date. The stories don’t say why drinking the colas would be a bad idea, but presumably plans were afoot to contaminate them. The story thus connects both to the Klingerman legend and to classic urban legends about contaminated products, especially tales of mice in Coke bottles.17Close Why Coke and Pepsi? What better way to sow terror than to tamper with the most ubiquitous consumer product on earth? Forbes reported in 2003 that 1.2 billion eight-ounce servings of Coke are consumed daily worldwide.18Close The Web site of the Coca Cola Bottling Company’s Indonesia branch devotes considerable space in its FAQ section to debunking “myths and rumours.”19Close

But back to our chronology. On September 22, my mother forwarded “Flight to Washington,” an anonymous note from someone who flew from Denver to Washington with a captain who gave the passengers a strength-in-numbers pep talk about how to subdue hijackers, if any should happen to be on board, and a crew member who urged the passengers to introduce themselves to each other and show each other family photos. The sender and forwarder comments were “The following is from a letter by a professional friend and her return flight to D.C. this week” and “This was passed along to me by a friend. Interesting.”

Here, I think, we’re seeing two influences coming into play. One is the stirring tale of the passengers on Flight 93 who tried to wrest control from the hijackers and succeeded to the extent that the plane crashed into a field in rural Pennsylvania rather than into its intended target, which might have been the White House or the U.S. Capitol. The other is the recognition that, for all the tough talk about revenge, the only opportunity most of us would have to confront the terrorists would be if we met up with them on a flight. Sooner or later, we were all going to have to resume normal activities, including flying. This was a way to steel ourselves for the experience.

An e-mail with a related message arrived on September 27. Called “I Forgot,” it places responsibility for September 11 on our own shoulders. Each time Osama bin Laden revealed his intentions in bombings throughout the 1990s, it says, we expressed outrage, then “forgot.” This time, the piece concludes, we must not forget:

Please, Please, Please, if you are reading this, don’t look away when they show the airplanes flying into the buildings on TV, look at it over and over again !! Don’t stick your head in the sand! Remember how despicable the act was, remember the loss of life, don’t shield your children, use restraint, but help them understand it, and remember it! They are our future! You will go back to work, and resume your daily duties, but, PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE, DON’T EVER FORGET! I assure you the terrorists around the world are counting on us to! AGAIN! I fear the next time we will see a mushroom cloud on our beautiful horizon! Then it will be too late! All because WE FORGOT!

“This One Will Make You Cringe”

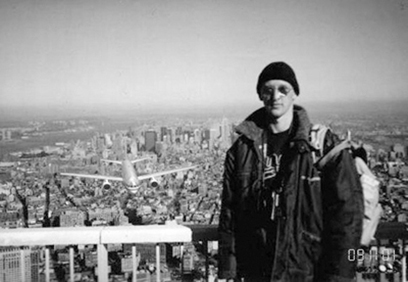

My brother-in-law sent me an unforgettable image on September 28, along with a noncommittal message: “Check this out.” Also included were prior forwarders’ similarly neutral messages: “If you haven’t seen” (September 26) and “This is interesting” (September 25). But the message that appears to have accompanied the original transmission goes like this: “This picture was developed from film in a camera found in the rebble of the wtc!!!!!! person in picture still not identified.” A tagline at the bottom of the photo said, “SUPPORT YOUR POLICE, FIRE, AND EMS PERSONEL.”

Another version of the accompanying message, reproduced on the Netlore Web site, appeared under the subject line “Different Perspective on the New York Tragedy”:

Attached is a picture that was taken of a tourist atop the World Trade Center Tower, the first to be struck by a terrorist attack. This camera was found but the subject in the picture had not yet been located. Makes you see things from a very different position. Please share this and find any way you can to help Americans not to be victims in the future of such cowardly attacks.

And a third version, on Snopes.com:

We’ve seen thousands of pictures covering the attack. However, this one will make you cringe. A simple tourist getting himself photographed on the top of the WTC just seconds before the tragedy… The camera was found in the rubble!!

“For just the briefest split-second of gut reaction,” wrote the Chicago Sun-Times columnist Richard Roeper, “we thought we were seeing one of the most astonishing photos in recorded history.”20Close On closer inspection, one sees that there are enough holes in this image to fly several airplanes through. Netlore enumerated most of them:

Why isn’t the fast-moving aircraft blurry in the photo?

Why doesn’t the subject (or the photographer, for that matter) seem to be aware of the plane’s high-decibel approach?

The temperature was between 65 and 70 degrees that morning. Why is this man dressed for winter?

How did the camera survive the 110-story fall when the tower collapsed?

How was the camera found so quickly amidst all the rubble?

Why has this one-of-a-kind, newsworthy photo not appeared in any media venue?

Many people were taken in by the original Tourist Guy image, which was usually accompanied by a message asserting the camera was found in the rubble and urging support for the troops.

Those were the obvious illogicalities. Roeper, who aptly referred to the images as “photographic urban legends,” pointed out more arcane clues to the images’ inauthenticity: “There was no observation deck on the north tower, and the deck on the south tower wasn’t scheduled to open until 9:30 a.m. that day.” Also, “The American Airlines jet shown in the photo is a Boeing 757, but the American Airlines plane that struck the tower was a Boeing 767.”21Close

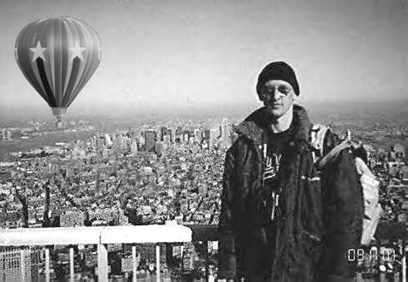

And so Tourist Guy, as he came to be called (or alternatively, the Ground Zero Geek, which I prefer), was revealed to be a hoax. Did that cause him to disappear from view? Hardly. As with e-mailed warnings, the hoax gave way to parodies of the hoax.22Close We see the same guy on the same observation platform. Only now a subway car is coming at him. Or a hot-air balloon. Or the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man from the 1984 movie Ghostbusters. Then, instead of the disaster coming to him, the Ground Zero Geek goes to the disaster: the crash of the Concorde in 2000, the bombing of the USS Cole at port in Yemen in 2000, the Kennedy motorcade in Dallas in 1963, the crash of the Hindenburg in 1937, the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, the sinking of the Titanic—the movie—in 1997, and President Lincoln’s box in Ford’s Theatre in 1865. He also drives the bus in the 1994 movie Speed and feels the hot breath of Godzilla on his neck. In a later version that only a New York Yankees fan can appreciate, Tourist Guy joins the Boston Red Sox in celebrating their 2004 World Series victory, their first since 1918.23Close

Once Tourist Guy was debunked as a fake, a succession of spoof versions followed.

In this version of Tourist Guy, the World Trade Center is menaced by the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man from the movie Ghostbusters.

An alternative tradition developed wherein Tourist Guy appears at the scene of various earth-shattering events, such as the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas in 1963.

The joke-within-the-joke in this image of Tourist Guy at the crash of the Hindenburg in Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1937, as with the Kennedy motorcade image, is the faux-digital date in the right-hand corner.

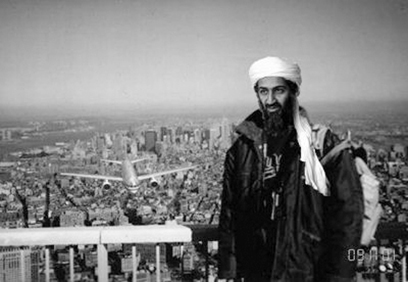

In another twist on the Tourist Guy tradition, the variable is Tourist Guy himself, here replaced by Osama bin Laden.

Finally, we go back to the observation platform and the looming menace of the plane, only now it’s not the disaster that has morphed into something else, but Tourist Guy himself. He becomes the owner of a giant cat named Snowball in one meta-parody—an image that was almost as popular on the Internet in 2001 as Tourist Guy—and none other than Osama bin Laden in another.

The news media devoted an enormous amount of attention to the seeming arbitrariness of fate. There were countless tales of people who were supposed to be on one of the four planes or at the World Trade Center but were delayed or had to change their plans. The stories emphasized the gratitude and guilt of these survivors. The dominant attitude was awe in the face of so many reminders of the slender thread on which our lives hang. Consider the following headlines:

The photoshoppers were also aghast at the precariousness of life but took a darker view. Sudden death makes a mockery of our plans. It is the ultimate cruel joke. Where the news media dwelled on the solemnity of it all, the newslore focused on the absurdity. If Osama bin Laden was the face of evil, Tourist Guy became the face of absurdity. He is the quintessence of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. In his ignorance of what is about to befall him, he represents all of us on the morning of September 11.27Close The stories about the real victims of that terrible day struggle to particularize them, to assert the meaningfulness of all their lives, in Jack Lule’s words, “to make sense of life in the face of the seeming randomness of human existence.”28Close Victims became heroes. Death became sacrifice. In contrast, newslore counters the pious approach with an anonymous, fictitious victim that allows for the expression of the subversive, unspeakable view. These deaths were senseless, absurd. We’re here one minute, gone the next. What’s heroic about it? We’re geeks, tourist guys, on planet Earth. As is often the case, the folkloric response may have been the more honest response.

The original Tourist Guy image was plausible, at least at first glance, more urban legend than joke. The apparent motive of the first wave of e-mailers was not to amuse but to appall. Once the picture had been debunked, however, the sense of victimization gave way to relief: Tourist Guy, like the rest of us, had survived. The endless permutations of Tourist Guy that followed, coinciding with the reduced sense of imminent threat as the days and weeks after September 11 passed without follow-up attacks, seemed to place September 11 in historical context: as horrific as it was, we had come through other horrific events. We would come through this one as well. The jokes do more than express anxiety; they grapple with it.29Close

The substitution of Osama bin Laden for Tourist Guy on the observation deck provides us with a segue into the trove of newslore that shifts the focus from the attack on “the homeland” as it was suddenly being called, to the counterattack on Afghanistan and Iraq.

Vengeance

As soon as Osama bin Laden’s name surfaced in connection with the September 11 attacks, the faceless enemy had a face. Following President Bush’s lead, much of the post-September 11 newslore was directed specifically at bin Laden, just as it had been directed at the Ayatollah Khomeini during the Iranian hostage crisis of the late 1970s and at Saddam Hussein during the Gulf War of the early 1990s.30Close Here is where our material becomes unprintable, at least by newspaper standards. In devising suitable punishments for bin Laden, the newslore brings together the contemporary meaning of cursing—using four-letter words—and the ancient meaning of wishing harm upon another person.31Close

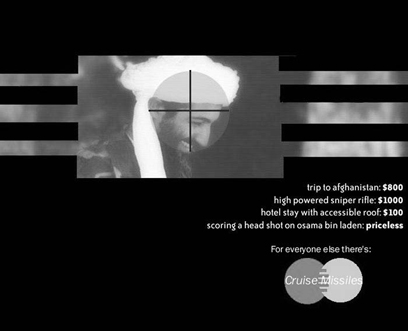

My collection of September 11 newslore includes a cycle of six photoshops that centers on the idea of targeting. Just as in 1979 Khomeini’s face appeared in a gun sight’s crosshairs in a photocopied cartoon that circulated via fax machine, so bin Laden’s face appeared behind a shooting-range target, on a dartboard, and in two pop-cultural parodies in a series of images that circulated by e-mail in fall 2001. In one, bin Laden appears in the crosshairs with the caption “Who wants to bomb a millionaire?” on the perimeter of the circle—a reference to the popular television program Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire? In the other, bin Laden appears in the crosshairs in a parody of a MasterCard company ad that offers an opportunity to assassinate him (we’ll look at the “Priceless” parodies in chapter 6). The parodying of commercial messages is consistent with what Elliott Oring found in the Challenger joke cycle, with its plays on well-known TV spots for beer (Bud Lite), shampoo (Head and Shoulders), and soft drinks (7UP).32Close Paraphrasing Dorst,33Close Bill Ellis, who includes the credit card spoof in his study of 9/11 lore, writes that topical jokes appropriate “mass media imagery in order to challenge official definitions of reality.”34Close

Another set of target images turns scatological. Just as the face of the president of Iraq appeared on a cartoon titled “Saddam Hussein Urinal Target” that was widely photocopied and faxed during the Gulf War in 1991, bin Laden’s face was emblazoned on a photoshopped urinal ten years later.35Close Both parody the targets designed to help in the potty training of little boys. Echoing the credit card parody’s characterization of bin Laden as “a piece of shit” another photoshop depicts a dog using bin Laden’s face as a target.36Close In a similar vein are the punning photoshops of bin Laden’s face on a roll of toilet paper. One carries the slogan “Get Rid of Your Shiite.” Another says, “Wipe Out Terrorism.”

Like the Mickey Mouse image we saw earlier, this item of photocopier lore featuring the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, spiritual leader of the Iranian revolution, dates back to the Iranian hostage crisis.

The updated, digital version of the 1979 image of Ayatollah Khomeini puts Osama bin Laden in the crosshairs.

This photocopied cartoon hints at public frustration that America could be victimized by such a technologically inferior adversary.

References to defecation lead, in turn, to an array of images that follow a chain of associations connecting defecation, military assault, and homosexual assault. Symbols of military and sexual aggression, Dundes and Pagter point out, are often interchangeable.37Close In combat, including the ritual combat of sports, Dundes writes, “one proves one’s maleness by feminizing one’s opponent. Typically, the victory entails some kind of penetration.”38Close To begin with antecedent material, there is the Gulf War cartoon of an American military plane chasing an Iraqi camel. Just as the plane “rides the camel’s ass”— with the appropriate “Holy shit!” response—so a warplane tails Osama bin Laden’s flying carpet or appears in the rearview mirror of his car in at least three variants that circulated in 2001.39Close A photoshop of the bat-wing B-2 bomber is inscribed with a parody of the bumper sticker designed to tweak tailgaters: “If you can read this, you’re fucked.”40Close Another photoshop shows a cache of missiles on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise with the words “Taliban-Brand Extra-Strength Suppository” stenciled on them.

Here the image of the flying carpet rather than the camel is invoked as an icon of the Middle East to highlight the disparity in military might between the United States and its latest enemy in the Islamic world.

Another set of images expresses the theme of homosexual assault through the use of the upraised middle finger. As Oring points out, the news anchors may offer reassurance and a sense of control in times of national trauma, but when it comes to expressing anger, they are too constrained by decorousness to be up to the task.41Close A final image with a more overt homosexual theme shows the martyrs supposed reward in heaven: seventy virgins, only the virgins are gay men.

In yet another cycle of photoshops, which corresponds to Ellis’s second wave of 9/11 lore,42Close the humiliations are heterosexual rather than homosexual, which reflects news reports of the puritanism and misogyny of fundamentalist Islamic movements such as the Taliban and the Wahaabi sect in Saudi Arabia, of which bin Laden is a member. One photoshop showed bin Laden being squashed by a large female bed partner. Depicting the al-Qaeda leader in any sort of sexual encounter shows disrespect for his religious beliefs. Showing the woman crushing him violates patriarchal folk ideas about man-on-top male dominance. A second image showed bin Laden pinned beneath a woman flexing her muscles while waving an American flag.

Photoshoppers gleefully devised suitable punishments for Osama bin Laden. This one responds to what appeared, at least to Western sensibilities, as a strong misogynistic streak in Islamic fundamentalism.

In the following genie joke, bin Laden is dominated in another way by three strong women who themselves were the subjects of a considerable outpouring of newslore in the 1990s:

Osama bin Laden found a bottle on the beach and picked it up. Suddenly, a female genie rose from the bottle and with a smile said, “Master, may I grant you one wish?”

“Infidel, don’t you know who I am? I need nothing from a lowly woman,” barked bin Laden.

The genie pleaded, “But master, I must grant you a wish or I will be returned to this bottle forever.”

Osama thought a moment. Then, grumbling about the inconvenience of it all, he relented. “OK, OK, I want to wake up with three white, American women in my bed in the morning. I have plans for them.” Giving the genie a cold glare, he growled, “Now, be gone!”

The genie, annoyed, said, “So be it!” and disappeared back into the bottle. The next morning, bin Laden woke up in bed with Lorena Bobbitt, Tonya Harding, and Hillary Clinton. His penis was gone, his leg was broken and he had no health insurance.

The backstory: Lorena Bobbitt experienced her brief brush with fame in 1993 when she cut off her husband’s penis. Tonya Harding had hers in 1994 when she hired a hit man to injure her Olympic figure-skating rival Nancy Kerrigan. As we saw in chapter 1, Hillary Clinton’s image suffered long-term damage when her husband made her chair of a task force charged with developing some sort of national health insurance. It is a measure of celebrity when veterans of old newslore resurface in new newslore.

In two final humiliating images, Osama bin Laden is not feminized but infantilized. One image parodies milk carton campaigns on behalf of missing children. On a container of “Afgan Farms” goat milk (“already expired”) it says: “Last seen: Mounting his donkey before crawling his skinny little pajama, towel headed lanky ass into some elusive Afghan cave.” The other image, a poster version, asks: “Have you seen me? I’m about to get my ass nuked off the face of the planet.”43Close This echoes an earlier milk carton parody of the Mars Explorer spacecraft with which NASA briefly lost contact in 2004.

The bin Laden connection also provided a geographic target: he was believed to be hiding in Afghanistan. The San Diego Union-Tribune columnist Joseph Perkins may have been one of the first to suggest that Afghanistan be “bombed back to the Stone Age.”44Close The next day, the New York Times reporter Barry Bearak grimly joked that the war-torn land was “already there.”45Close The idea of bombing back to the stone age, which the San Francisco Chronicle columnist Rob Morse reminded readers was a recycled Vietnam-era quote from General Curtis LeMay,46Close and the observation that Afghanistan was already there, appeared in scores of newspaper columns and stories. The newslore was more creative. The desire to lay waste to Afghanistan found pictorial expression in cybercartoon maps showing the country transformed into either a lake or a parking lot (the radio talk show host Howard Stern reportedly made the same suggestion on the air).47Close Dundes and Pagter found similar maps of Iraq-as-parking-lot during Operation Desert Storm.48Close As Ellis noted,49Close the urge to flatten Afghanistan also found expression in several riddles:

Q:How is Bin Laden like Fred Flintstone?

A:Both may look out their windows and see Rubble.

Remember that the Flintstones were a “modern Stone Age family” and that Fred Flintstone’s neighbor and pal was Barney Rubble. Some other riddles and jokes with annihilation themes:

Q:What do Osama bin laden and General Custer have in common?

A:They both want to know where those Tomahawks are coming from!

Q:How do you play Taliban bingo?

A:B-52…F-16…B-1…

Q:What do Bin Laden and Hiroshima have in common?

A:Nothing, yet.

Q:What’s the five-day forecast for Afghanistan?

A:Two days.

A variant:

Forecast weather for; Kabul, Karachi, Baghdad and Damascus for the week of 9/24/2001: Very brief period of extremely bright sunlight followed by variable winds of 2000 knots and temperatures in the mid to upper 6000 degrees range with no measurable moisture. SPF 12000 sun block highly recommended if standing near an outside structural wall of less than one meter thick.

Q:What is the Taliban’s national bird?

A:Duck.

Nothing Sacred

Until this point, the only 9/11 jokes we’ve seen have been at the expense of the perpetrators and their allies (or supposed allies)—Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, Afghanistan, Iraq, the Arab world in general. For a long time, I had the impression that jokes about victims of the 9/11 attacks were off-limits. Alas, they were not. In the interest of completing the record, I offer the following examples:

Q:What does WTC stand for?

A:“What Trade Center?”

[This is a common riddle type. After the Challenger disaster, for example, we learned that NASA stood for “Need Another Seven Astronauts,” among other things. After the bombing of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, we leaned that Waco stood for “We Ain’t Comin’ Out,” “We All Cremated Ourselves,” etc.]

At the World Trade Center restaurant, they offered three seating areas: smoking, non-smoking and burned beyond recognition.

They don’t need any more volunteers to help at the WTC: they have found 5000 extra pairs of hands …

Q:What is world most efficient airline?

A:American Airlines, leave Boston 8:15 … be in your office in New York 8:48!

America’s new math:

Q:Now how many sides to a Pentagon?

A:4.

If one side of the Pentagon has collapsed, will it now be renamed “The Square”?

Q:Why are police and firemen New York’s finest?

A:Because now you can run them through a sieve.

A man goes to the World Trade Center. He says, “I want to buy a jumbo jet.”

“We don’t sell jumbo jets here, sir,” was the reply.

“Well, you’ve got one in the window!”

Q:What’s the difference between 9/11 and the Oklahoma City Bombings?

A:Once again, foreigners have proven that they can do it better and more efficiently.

I should note that these jokes did not come my way as e-mail forwards. I found them on various humor Web sites. The jokes aggressively refute the notion that there are some things one just does not joke about. While the knee-jerk reaction would be to deplore the insensitivity of this material, it could also be looked at as an ostentatious display of tough-mindedness and defiance. “If I laugh at any mortal thing,” Byron writes, “’Tis that I may not weep.”50Close I think of the scene in the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail where the Black Knight refuses to surrender even after King Arthur lops his arms off. “Just a flesh wound,” he says.

Giselinde Kuipers wisely cautions that interpreting the sick 9/11 jokes as a coping mechanism assumes that everyone was traumatized by the attacks— which may not be warranted. Doubtless there were those who didn’t see what all the fuss was about and said as much in the jokes. (After all, as a New York Times story noted in 2008, “the chances of the average person dying in America at the hands of international terrorists [is] comparable to the risk of dying from eating peanuts, being struck by an asteroid or drowning in a toilet.”)51Close The jokes, Kuipers writes, “defy the moral discourse of the media, provide the pleasure of boundary transgression, and block feelings of involvement.”52Close The defiance, in other words, is not of the terrorists but of the taboos against offensive humor.

Unfit to Print

When big news happens, reporters, as a matter of course, will report what happened and how people reacted to what happened. If the event is deemed to be of major importance, a separate reaction story will run alongside the main news story. By any measure, the September 11 attacks were the biggest story in the history of American journalism. Beginning with extra editions that hit the streets on the afternoon of September 11, coverage included not just one-story roundups of the latest developments but multiple stories, including stories that focused exclusively on the reaction—from world leaders, from members of Congress, from military personnel, from terrorism experts, from clergy, from people in the street at home and abroad, and so on. The New York Times devoted an entire section to 9/11 follow-up stories throughout the fall of 2001.

The stories are inevitably balanced. The rituals of objectivity require reporters to present, if not a range of viewpoints, at least representative expressions of opposing views. The message to readers is that, in its news columns, the paper does not privilege one view over another. It does, however, limit its sampling of views to those that do not violate the canons of good taste. The dual imperatives of balance and taste produce a muting effect. There is anger in the post-September 11 reaction stories, but it seems restrained compared to the revenge fantasies that are played out in the folklore.

On September 19, for example, USA Today asked, “Do we seek vengeance or justice?” and noted that “the sentiments of Americans run the gamut.” Four voices calling for rage and retribution followed, including one who said, simply, “Nuke ’em.” Then came the balancing act: “Others prefer the guidance of the old saying ‘Revenge is a dish that is best served cold.’”53Close

The St. Petersburg Times noted that polls showed “overwhelming support for a military response” and illustrated the point with a quote from a local official that was as risqué as most general-circulation American newspapers ever get: “I think we need to go kick some ass big time.” After three other blustery quotes, though, the story turns to the more measured responses: “While most Americans support whatever action is necessary, not everyone is quite ready for what that could mean.”54Close

A September 14 story in the New York Times began thus: “Having donated more blood than victims needed, having wallpapered their towns with flags, and with little choice but to stew over television reruns of terror in their homeland, more than a few Americans are beginning to obsess about how to get even.” One interviewee suggested that we find and kill “these Arab people,” then “wrap them in a pigskin and bury them. That way they will never go to heaven.” Another said, “If I could get my hands on bin Laden, I’d skin him alive and pour salt on him.” Such talk, the reporter Blaine Harden noted, “also alarmed many Americans.”55Close

Another New York Times story, “Fantasies of Vengeance, Fed by Fury,” on September 18, included calls for parading bin Laden’s head through the city on a pike, burning him alive, and “nuking” Kabul.56Close Then President Bush himself weighed in, invoking “Wanted: Dead or Alive” posters from the old West. The Times disapproved, taking the president to task in its lead editorial for his “overly bellicose” language.57Close

Taken together, these stories and others like them offer specific evidence of American anger. But that anger found its fullest and most profane expression in the newslore that circulated among friends and acquaintances via e-mail. Americans weren’t just angry about the September 11 attacks, they were cursing angry. Studies of the sick jokes that greeted the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986 suggest that the jokes were a response not only to the disaster itself but also to the disaster story—in other words, to the solemnity and piousness of the news media’s narrative of the disaster.58Close

While it may seem obvious that much contemporary folklore responds to current events, it is easy to forget that, strictly speaking, the lore responds not to the events themselves but to accounts of the events. As countless sociological and rhetorical studies of news have pointed out, the news is a story about an occurrence.59Close As such, it is important to recognize that newslore may be a response to how that story is told—to what is left out as well as what is included—as much as it is a response to the occurrence itself.

No one, other than people who were close enough to the launch site to see it in person, could have known about the Challenger explosion other than by seeing it on television, hearing about it on the radio, reading about it in the newspaper the next day (this was before newspapers had Web sites), or hearing about it from someone who had been paying attention to the mass media.60Close For those of us who watched the disaster on TV, the experience was visually framed and reduced by the screen itself, bracketed by the commercial messages that underwrite the news programming, and filtered through the personality of whichever news anchor told us the story. The juxtaposition of extraordinary tidings with the business-as-usual production values and fiscal imperatives of network news was jarring and more than a little absurd.

Oring argues that the Challenger jokes were a “strategy of rebellion” against the slick media packaging of the disaster. Part of that strategy was to effectively bar the news media from appropriating the jokes by making them unspeakable according to the news media’s canons of good taste.61Close Oring infers public attitudes toward the “packaging” of disaster from the content of the jokes themselves—and from the cultural knowledge one would need to possess to understand the content. Here, contrasting the newslore of September 11 with the expressions of rage and dismay that were deemed fit for public consumption has shown how newslore functions as an alternative discourse on disaster. Like the accused miscreant who makes an obscene gesture at the cameras during his perp walk, those with a taste for newslore can fight off news media co-optation and thereby maintain the world of computer-mediated communication as a parallel or underground universe of discourse simply by making the material “unspeakable.”

Sure enough, as exhaustive as news coverage of September 11 and its aftermath was, when I searched for stories about the newslore of September 11, I found that the American news media mostly ignored or toned down “tasteless” expressions of public anger so as not to offend their audiences. A USA Today story about humor on the Web noted that the goat milk carton emblazoned with the image of Osama bin Laden contained “language unsuitable for a family newspaper.”62Close A Rocky Mountain News story mentioned photos of bin Laden “in none-too-flattering poses.”63Close Anything more explicit, presumably, was simply not fit to print. As Christie Davies wrote of jokes about the death of Princess Diana, “Such jokes never appear on radio or television or in established newspapers, for media executives stringently censor out any such material lest an influential or vociferous segment of their audience feel offended.”64Close (I would note that the media executives need not get involved; the canons of good taste are widely shared among the newsroom rank and file.)

The Pew Internet and American Life Project, incidentally, also gave the folklore of 9/11 a wide berth. The project’s sixty-five-page study of how Americans used the Internet in the aftermath of September 11 noted that “the Internet became a channel for anguished and prayerful gatherings, for heartfelt communication through email, and for vital information”65Close but made no mention of jokes or humor apart from observing the presence of rumors and other “fanciful tales.”66Close Snopes got a mention for its role in debunking rumors, as did Fark.com for abandoning its usual comedy format to deliver straight news.

Elsewhere, the Pew report acknowledged that the Internet “provided a virtual public space where grief, fear, anger, patriotism and even hatred could be shared,”67Close but only addressed direct statements of those sentiments and not their expression in the more stylized or artistic forms of folklore. Similarly, a section on images listed six kinds of images but ignored cartoons and photoshops.

Meanwhile, with the acquiescence of a shockingly docile news media and Democratic opposition, the Bush administration ordered the invasion of Iraq and toppled Saddam Hussein—so far, so good—but U.S. forces were unable to restore order once Saddam’s army had disbanded and dispersed. Though polls showed that a majority of Americans continued to believe that Saddam had his hand in the September 11 attacks and possessed weapons of mass destruction long after conclusive evidence to the contrary came to light, eventually the sense that we were bogged down in Iraq while Osama bin Laden remained at large eroded popular support—and the change seems to have been reflected in the newslore.

A good starting point for a discussion of antiwar—and therefore anti-Bush—newslore is the juxtaposition of two wildly contradictory Bush statements:

September 13, 2001: “The most important thing is for us to find Osama bin Laden. It is our number one priority and we will not rest until we find him.”

March 13,2002: “I don’t know where he is. I have no idea and I really don’t care. It’s not that important. It’s not our priority.”

A similar juxtaposition of Bush quotations was captioned “Two-Faced Bush”:

May 29, 2003: “We’ve found the weapons of mass destruction. And we’ll find more weapons as time goes on.”

February 7, 2004: “There’s theories as to where the weapons went. They could have been destroyed during the war.”

The other major contributor to turning the tide of public opinion against the war was the set of photographs taken—and shared, folklore-like—by American military personnel detailed to the Abu Ghraib prison. The visual evidence of prisoner abuse shocked the public—and lent itself to pointed photoshops, including images where a smirking Bush (and, in some instances, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld) was substituted for the faces of guards at Abu Ghraib. The most searing image, the hooded prisoner with electrodes attached to his fingers, appeared as the White House Christmas tree, under the “Mission Accomplished” banner under which Bush appeared on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in the original photo taken on May 2003, and on the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, among other places. As we will see in chapter 5, Bush had been skewered before his election—and before September 11—as a stooge, a chimp, a dunce, and a puppet of his father or of Dick Cheney or his friends in the oil industry. But when things began to go wrong in Iraq, the newslore took on a harder edge. Bush’s supposed lack of qualifications for the highest office in the land became more disturbing—and the newslore more condemnatory—as the stakes rose, as they did again in 2005 when the Bush administration seemed woefully inept in its response to Hurricane Katrina.

For the full text of Sinclair’s column, see http://www.snopes.com/politics/quotes/sinclair.asp.

Pitts 2001. The column earned Pitts the Pulitzer Prize for commentary the following year.

The jokes began flowing into the in-box of the Washington Post columnist Gene Weingarten (2001) a little sooner: “The time, for all those keeping score, was 5 days 2 hours 8 minutes and 1 second. That was the hiatus between the arrival of the first plane at the North Tower of the World Trade Center, and the arrival of the first known attempt at Internet humor on the subject.” The jokes were anagrams of the name Osama bin Laden: “Is a banal demon.” “I am a bland nose.” “No! A mad lesbian.” “Animals on a bed.” Weingarten was unimpressed. Christie Davies (1999, 253) reports receiving his first two Princess Diana jokes within forty-eight hours of her death.

Kuipers (2005, 78) and Ellis (2002, 4) include this image in their studies of the humor of 9/11.

Much of the newslore of September 11 echoed the folkloric responses to the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979 and the Gulf War in 1991. See Dundes and Pagter 1991a.

See Snopes for further discussion of the Klingerman virus: http://www.snopes.com/medical/disease/klingerman.asp.

For a discussion of the Halloween warning, see http://americanhistory.about.com/cs/blmall-terror.htm.

Bronner 1995, 173–76.

See Gibes 2001.

Hathaway (2005, 42) aptly compares Tourist Guy’s wanderings to the phenomenon of the traveling garden gnome.

Tomsho, Carton, and Guidera 2001. Similar headlines appeared in San Francisco Bay Area newspapers in the immediate aftermath of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

“In many ways, we are all ‘Tourist Guy’ to the events of 9/11,” writes Hathaway (2005, 43).

For further discussions of Tourist Guy, see http://www.touristofdeath.com; http://urbanlegends.about.com/od/mishapsdisasters/ig/Tourist-Guy/touristguy.htm; http://www.snopes.com/rumors/photos/tourist.asp.

Ellis 2002, 2.

Kuipers (2005, 78) mentions these “degrading pictures” in her study.

Dundes 1997, 27.

Ellis 2002, 8.

Hinckley 2001. Kuipers (2005) and Ellis (2002) cite the lake maps.

Ellis 2002, 8.

Quoted in deSousa 1987, 234.

Kuipers 2005, 81.

See, for example, Gans 1980; Fishman 1980; Schudson 1989; Bird and Dardenne 1997.

Oring 1987; see also Smyth 1986.

Davies 1999, 254.

Found at http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/images/blbushtwofaces.htm (and credited to politicalstrikes.com).

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| August 2024 | 1 |