-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paul S Jeong, Recognizing Moyamoya Disease in a Soldier With Recurrent Cerebrovascular Symptoms, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages e2769–e2771, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usab564

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Moyamoya is a rare and progressive cerebrovascular disease involving collateral small vessel formation associated with intracranial artery narrowing. It is a disease that frequently presents with stroke and transient ischemic attacks and has potential to affect our active duty service members and their families with its bimodal age of onset of 10 and 40. This case report describes a soldier with moyamoya whose diagnosis was unrecognized for over a year after seeing multiple medical providers regarding his symptoms. The goal of this case report is to raise vigilance for this disease as it can cause significant morbidity and mortality with mental decline, recurrent strokes, and death without timely surgery.

INTRODUCTION

The term moyamoya is Japanese for “puff of smoke,” which describes the collateral small vessel formation associated with intracranial artery narrowing. Although the disease is found worldwide, its incidence is higher in Asian countries than in Western countries, and it affects both adults and children.1,2,3 This report describes a case of a young active duty soldier whose diagnosis of moyamoya was initially unrecognized as he continued to serve on active duty while experiencing exertional transient ischemic attack (TIA) symptoms.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A 35 year old Asian male soldier with a history of hypertension and cigarette smoking was walking on an Expert Field Medical Badge (EFMB) testing lane overseas when he had an episode of left hand and leg numbness. He presented to the theater clinic that day reporting 1 year of intermittent, semimonthly left upper and left lower extremity numbness that had never been evaluated. The symptom that caused him to seek evaluation this time was new weakness in his left hand that lasted 30 minutes. Neurological examination to include sensation and strength at the time was normal, and he was cleared to continue as EFMB personnel with close primary care follow up and strict return precautions.

Two months later, he saw his battalion flight surgeon to whom he reported a history of dragging his left leg when these symptoms occur. An MRI brain with gadolinium was obtained that showed nonspecific right greater than left cerebral T2 hyperintense white matter foci with subtle enhancement of a right frontal white matter focus. Findings were thought to be related to an infectious/inflammatory etiology, and he was transported via medevac to the USA where he was able to see a neurologist. He reported an increased frequency of symptoms to 5–10 times per day with symptoms triggered by stress and standing up. He also reported urinary frequency with post-void fullness concerning for neurogenic bladder and multiple sclerosis. With McDonald criteria showing >2 clinical attacks and 1 lesion, a lumbar puncture looking for oligoclonal bands in CSF was indicated, and the procedure was performed successfully. In order to evaluate for autoimmune, inflammatory, infectious, and metabolic etiologies for his symptoms, CSF samples were sent for oligoclonal bands, glucose, protein, cell count, gram stain/culture, and myelin basic protein in addition to serum labs for ESR/CRP, Treponema pallidum IgG, ANA, and TSH. His neurologist subsequently reviewed the soldier’s brain MRI again and noted that the right frontal lobe white matter lesion did not have a classic Dawson fingers appearance and that there were no other MS-type lesions. As the CSF and serum labs were unrevealing in the setting of zero oligoclonal bands in the CSF, his neurologist concluded the evaluation with the thought that his recurrent symptoms were due to a single ischemic lesion in his right motor strip region with small vessel ischemic disease due to intermittent cigarette smoking and a long history of hypertension. He had been diagnosed with hypertension at age 32 with a family history of hypertension in his mother, and no evaluation for secondary hypertension was done. He was recommended to maintain normal blood pressure, quit smoking, and start aspirin 81 mg daily. There was no mention of a need for further workup or vessel imaging with MR angiography (MRA) or CT angiogram (CTA), and the soldier returned overseas. He continued to have recurring symptoms and was recommended to continue normal duty.

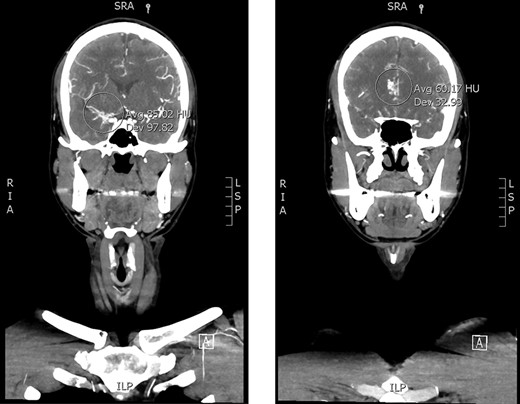

Several months later he was relocated to Maryland and saw a medical provider who noted that his recurring symptoms were triggered by sleep deprivation and physical exertion and were atypical for a single ischemic event. He was referred to a neurologist whose differential included a vascular etiology (e.g., focal stenosis of right MCA or carotid), epileptic etiology, genetic etiology (e.g., mitochondrial disorder), or hemiplegic migraines. Vascular etiology was thought possible as the spells were triggered by physical activity in the setting of his vascular risk factors. Epileptic etiology was thought possible given the stereotyped spells but was thought unlikely with negative phenomena. Mitochondrial disorder was possible given the stroke-like episodes with his associated mild aminotransferase elevations, but he did not have family history of such a disorder, and the MRI did not have the typical pattern. Hemiplegic migraine was considered as well, but he did not have an associated headache. His workup was expanded to include labs to evaluate a mitochondrial etiology with creatine kinase, LDH, pyruvate, amino acid profile, acylcarnitine profile, and urine organic acid. An electroencephalogram was performed to evaluate for an epileptic etiology, and a CTA head/neck was performed for vessel imaging. Mitochondrial labs and electroencephalogram were unremarkable, but the CTA showed likely moyamoya on the right-sided anterior circulation (see Fig. 1). Subsequent digital subtraction angiography was performed showing moyamoya of the right ICA, MCA, and ACA. The soldier was placed on a profile with plan for medical board evaluation for his recurrent TIAs. An uncomplicated right-sided craniotomy and indirect bypass with superficial temporal artery encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis (EDAS) was performed by neurosurgery resulting in reduced frequency of weakness and tingling. After his procedure, a medical board process was initiated. Eight months after his procedure, a follow up cerebral angiogram showed robust pial synangiosis supplying the majority of the lateral right frontal lobe. Subsequently, an 11 month post-procedure nuclear brain perfusion study showed mildly improved perfusion involving the right superior frontoparietal region. He proceeded to prepare for medical retirement and was recommended to continue with a very slow, gradual increase in physical activity and follow up with neurosurgery every 6 months. Continued progressive collaterals were to be expected over the next several months and the possibility of an additional EDAS was discussed should he experience worsening neurologic symptoms in the future.

CTA head/neck. Asymmetric small caliber of the right-sided anterior circulation with venous engorgement versus collateral flow at the right sylvian fissure (left) and pericallosal region (right) concerning for moyamoya.

DISCUSSION

The highest prevalence of moyamoya disease is found in Japan, China, and Korea.1,2,3 Genetics seem to have an important role as approximately 15% of cases are thought to be familial.4 Adults and children are both affected with a bimodal age of onset of 10 and 40, suggesting that service members in our active duty population and their families can be affected. Moyamoya most commonly presents with ischemic stroke and can also frequently present with TIAs.5,6 Intracerebral hemorrhage is also a significant complication of moyamoya and is more common in adults than children.7 Patients can also, albeit infrequently, present with seizures secondary to the ischemic damage that occurs.8

Moyamoya should be on the differential especially for young patients who develop recurrent stroke-like symptoms (as was the case for this soldier) or young patients who develop strokes without common cerebrovascular risk factors. Suspicion should be even higher for those of East Asian descent as the disease is most prevalent in this population. This soldier’s brain MRI did not raise concern for moyamoya, but the CTA raised moyamoya as a likely diagnosis. Likewise, a CTA or MRA should be considered as a primary component of an initial evaluation for moyamoya in the appropriate clinical scenario given its noninvasive nature and high diagnostic yield.9,10

In the case of this active duty soldier, significant coordination and resources were involved in transporting him to the USA for an evaluation that did not reveal his underlying condition. Had a MRA or CTA been performed, his moyamoya would have been discovered and treated sooner, and the resources used to transport him to the USA may have returned a far more rewarding outcome. It is significantly important to complete a thorough diagnostic evaluation for service members on medical temporary duty travel before they depart their higher level of care. If concern for moyamoya arose for this soldier overseas after his return from his initial evaluation in the United States, he may have had to travel via medevac again for neurosurgical intervention.

Moyamoya and its complications can cause significant morbidity and mortality, which is why recognizing the disease early is of great importance. With the progressive nature of the disease, many will experience mental decline and recurrent strokes without timely surgery.11 Military clinicians should remain vigilant in recognizing the differential diagnosis of stroke in young active duty service members and their dependents while evaluating for moyamoya in those with a compatible clinical presentation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.