-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michael Burns, Paul Robben, Ramesh Venkataraman, Lyme Carditis With Complete Heart Block Successfully Treated With Oral Doxycycline, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages e2702–e2705, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usab420

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Lyme disease is a vector-borne infection that can affect multiple different organ systems. Lyme carditis represents one of these sequelae and is defined by acute onset of high-grade atrioventricular block in the presence of laboratory-confirmed infection. Current guidelines recommend patients with Lyme carditis be admitted for close cardiac monitoring and intravenous antibiotics therapy. Our case illustrates an active duty male who was initially diagnosed with Lyme disease after initially reporting symptoms including headache, fever, eye pain, and rash, with subsequent development of exercise intolerance 6 weeks later. An electrocardiogram (ECG) obtained at that time was misinterpreted as first-degree heart block, and he was initiated on oral doxycycline therapy and referred to cardiology. On follow-up to cardiology clinic, the prior ECG was reviewed and interpreted as complete heart block. A repeat ECG showed resolution of the heart block, and exercise stress testing showed chronotropic competence. This case illustrates the resolution of complete heart block in Lyme carditis with oral doxycycline, suggesting this antibiotic as a possible alternative treatment agent.

INTRODUCTION

Lyme disease is a vector-borne infection caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdoferi that is transmitted by the Ixodes tick. Over 33,000 cases of Lyme disease were reported by the CDC in 2018 (the most recent data reported), although it is suspected that number may be higher due to incomplete reporting.1 It also represents the most common vector-borne disease in the U.S. military.2 Although Lyme disease is typically associated with the characteristic erythema migrans (EM) rash and polyarthritis, multiple other systems, including neurologic and cardiovascular systems, can be affected. Lyme carditis is characterized by the acute onset of high-grade atrioventricular (AV) conduction defects in the presence of laboratory-confirmed infection and absence of an alternative diagnosis and manifests in approximately 1% of Lyme disease patients.1 Symptoms typically include syncope, lightheadedness, lethargy or weakness, chest pain, and palpitations. Although early localized Lyme disease is most commonly treated with oral doxycycline, current recommendations for the treatment of Lyme carditis are hospitalization and intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone.3 Our case presents a patient with Lyme carditis manifesting as complete heart block who was successfully treated with oral doxycycline.

CASE REPORT

The patient is 26-year-old active duty military male living in Maryland with history of well-controlled ulcerative colitis and reported cephalexin allergy who initially presented to his primary care physician (PCP) with symptoms of headache, fever, eye pain, and rash. His rash was described as multiple erythematous patches located on his right forearm, right wrist, left thigh, and abdomen below the umbilicus. He was given a diagnosis of viral infection and counseled on return precautions for his symptoms did not resolve. Six weeks later, when he presented for a routine exam, he reported resolution of his initial symptoms but worsening exercise intolerance and weight loss. Electrocardiogram (ECG) obtained by the PCP was interpreted as mild first-degree AV block. Laboratory work-up was significant for serum C-reactive protein elevated to 1.491 mg/dL (reference range 0-0.500 mg/dL); serum Borrelia burgdorferi antibody positive; and Lyme Western Blot positive for three of three immunoglobulin M (IgM) bands and seven of 10 immunoglobulin G (IgG) bands (Table I). The patient was initiated on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily to complete a 3-week treatment course and due to the abnormal ECG was referred to cardiology for evaluation.

| IgM serologies (kD) . | Results . | IgG serologies (kD) . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Present | 18 | Present |

| 39 | Present | 23 | Present |

| 41 | Present | 28 | Absent |

| 30 | Absent | ||

| 39 | Present | ||

| 41 | Present | ||

| 45 | Present | ||

| 58 | Present | ||

| 66 | Absent | ||

| 93 | Present |

| IgM serologies (kD) . | Results . | IgG serologies (kD) . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Present | 18 | Present |

| 39 | Present | 23 | Present |

| 41 | Present | 28 | Absent |

| 30 | Absent | ||

| 39 | Present | ||

| 41 | Present | ||

| 45 | Present | ||

| 58 | Present | ||

| 66 | Absent | ||

| 93 | Present |

Western Blot serologies used to support the diagnosis of Lyme disease in our patient. IgM = Immunoglobulin M; IgG = Immunoglobulin G; kD = kilodaltons.

| IgM serologies (kD) . | Results . | IgG serologies (kD) . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Present | 18 | Present |

| 39 | Present | 23 | Present |

| 41 | Present | 28 | Absent |

| 30 | Absent | ||

| 39 | Present | ||

| 41 | Present | ||

| 45 | Present | ||

| 58 | Present | ||

| 66 | Absent | ||

| 93 | Present |

| IgM serologies (kD) . | Results . | IgG serologies (kD) . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Present | 18 | Present |

| 39 | Present | 23 | Present |

| 41 | Present | 28 | Absent |

| 30 | Absent | ||

| 39 | Present | ||

| 41 | Present | ||

| 45 | Present | ||

| 58 | Present | ||

| 66 | Absent | ||

| 93 | Present |

Western Blot serologies used to support the diagnosis of Lyme disease in our patient. IgM = Immunoglobulin M; IgG = Immunoglobulin G; kD = kilodaltons.

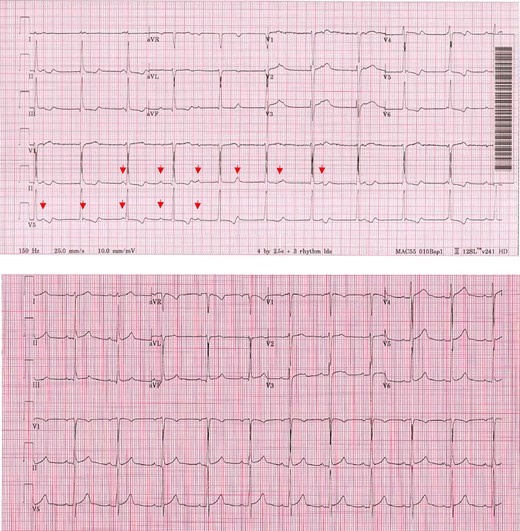

On presentation and records review 2 weeks later in our cardiology clinic, initial ECG was reviewed and determined to show sinus rhythm with complete heart block and a junctional escape rhythm (Fig. 1, top). In the cardiology clinic, a repeat ECG was performed, showing normal sinus rhythm and resolution of previous high-degree AV block (Fig. 1, bottom). An exercise stress test showed chronotropic competence. The patient was admitted overnight for continued cardiac monitoring. The infectious diseases inpatient service was consulted to determine if IV antibiotic therapy would be required and what alternate agents would be recommended given the patient’s cephalosporin allergy. Given the patient’s improvement in symptoms and absence of ECG/telemetry abnormalities, he was discharged home the next day to complete his 3-week course of doxycycline.

At follow-up in the cardiology clinic 2 months later, the patient continued to report absence of symptoms. A repeat exercise stress test continued to show normal sinus rhythm without evidence of AV block.

DISCUSSION

The clinical impact of Lyme disease is obvious within the U.S. Armed Forces, as it represents over 40% of all reported vector-borne diseases. Over the last 4 years, Lyme disease is the second most common cause of hospitalization among vector-borne diseases, averaging over 6 hospital bed days per hospitalization.2 Multiple large military bases are located within Lyme endemic areas within the USA and Europe, and service members often travel to these areas and spend time outside as part of both official and unofficial training and duties. As such, all military physicians, regardless of practice location, need to be familiar with the diagnosis and treatment of all sequelae. The ability to promptly recognize Lyme disease is critically important for military readiness as well, as later sequelae have increased morbidity that can be avoided if Lyme disease is diagnosed and treated early.

Lyme disease symptomatology is typically classified into three stages. Stage 1, also known as early localized disease, occurs within weeks of the initial infection. The symptom most commonly associated with Lyme disease is the pathognomonic EM, or “bull’s eye,” rash, often accompanied by an array of constitutional symptoms including fatigue, myalgias, headache, and fever. It is important to note that although pathognomonic, the EM rash is not always obvious, and when a non-characteristic rash is combined with other constitutional symptoms, early Lyme disease is often mischaracterized as a viral syndrome. When the EM rash is identified, it supports the diagnosis of Lyme disease and treatment should be initiated. Current recommended treatments include oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days or 14 days of either oral amoxicillin 500 mg 3 times daily or oral cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily.3

Stage 2, or early disseminated disease, occurs weeks to months after infection and can have neurologic (e.g., meningitis and Bell’s palsy) or cardiac manifestations. Late stage, or Stage 3 disease, occurs months after initial infection and is characterized by mono- or oligo-arthritis. Current diagnostic criteria for early disseminated and late disease include a two-tiered system: first checking an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or indirect fluorescent antibody test that if positive is followed by an IgM and IgG Western blot. A modified two-tier system comprising of two different EIAs can also be utilized. It should be noted that early disease can yield false-negative test results in the first 2 weeks following the development of the EM rash.3

Multiple cardiac manifestations have been associated with Lyme disease, including conduction block, atrial fibrillation, and myocarditis. Lyme carditis carries a favorable prognosis if treated promptly.4 Accurately establishing the likely diagnosis of Lyme carditis is the cornerstone for rapid initiation of treatment. As evidenced in our case, however, the vague, non-specific symptoms of early Lyme disease provide an avenue for delays in recognition and treatment and the development of more serious cardiac sequelae. Further, in a case review by Forrester and Mead of Lyme carditis patients with third-degree heart block, only 44% of patients reported the pathognomic EM rash, compared to 70-80% of all Lyme disease patients.5

Recently updated clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) continue to recommend collection of an ECG only in those patients with signs or symptoms consistent with Lyme carditis. Inquiring about and recognizing suggestive signs and symptoms, including dyspnea, edema, palpitations, lightheadedness, exercise intolerance, chest pain, presyncope, and syncope, is critical for prompt diagnosis and treatment.3 Marx et al. recently described two patients, both of whom reported at least two of these associated signs and symptoms, with ECG abnormalities later confirmed to be due to Lyme disease.6 Unfortunately, delays in treatment initiation led to death in both patients, highlighting the importance of early recognition and treatment.

For patients found to have a PR interval <300 milliseconds and no other arrhythmia or signs of heart failure or myopericarditis, current IDSA guidelines recommend outpatient treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg oral twice daily for 14-21 days.3 Inpatient care is recommended for patients who will benefit from the supportive care and/or continuous ECG monitoring, to include those with heart failure, myopericarditis, high-grade AV conduction defects or other arrhythmias, or PR interval >300 milliseconds (associated with an increased risk of sudden development of higher grade block). For these patients, initiation of antibiotic therapy with IV ceftriaxone followed by the transition to oral therapy once there is evidence of clinical improvement to complete a 14- to 21-day course of therapy is recommended.3 Patients with high-degree AV block may also benefit from temporary pacemaker placement. Given that most cases of heart block resolve around 6 days, permanent pacemaker is typically not indicated, unless heart block persists beyond 14 days.5 In patients with resolved heart block, a pre-discharge stress test is recommended to assess stability.4

Our case adds support to the argument that for many Lyme carditis patients, oral doxycycline may be a viable first-line therapy that could spare the higher costs and increased risk of adverse events associated with IV ceftriaxone. Ceftriaxone achieves high tissue concentrations (>4 µg/g) in heart tissues within the first 1.5-2 hours after a single 1-g dose.7 Similarly, doxycycline serum concentrations peak within 2-3 hours after a single oral dose of 100 or 200 mg and has been shown to rapidly achieve high concentrations in myocardial tissue.8,9 Moreover, in their 2015 review on Lyme carditis cases presenting as third-degree heart block, Forrester and Mead identified 13 patients who were treated successfully with tetracycline class antibiotics, compared to 78 treated primarily with ceftriaxone or penicillin; however, many of these cases were concurrently treated with steroids, a practice that has fallen out of favor in recent guidelines.5 Additionally, oral doxycycline has already been investigated in patients with neurologic symptoms of meningitis or radiculopathy, one of the two other Lyme disease sequelae for which IV ceftriaxone is recommended as the first-line treatment (recurrent/refractory arthritis being the third).3 In a recently conducted multicenter, open-label, randomized trial conducted in Europe, Kortela et al. showed that treatment of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis with oral doxycycline resulted in equivalent outcomes when compared to IV ceftriaxone.10 Identifying whether IV ceftriaxone provides benefit beyond oral doxycycline in Lyme carditis patients requiring admission warrants further investigation in controlled inpatient settings.

CONCLUSIONS

Our case demonstrates the importance for military health providers to stay well practiced in ECG interpretation, especially in the identification of life-threatening arrythmias to include third-degree AV block. Our patient recovered without any significant adverse effects or long-term sequelae despite initially only receiving oral antibiotic therapy; however, delays in diagnosis of Lyme carditis could have deadly consequences. Although oral doxycycline may be a viable alternative therapy for Lyme carditis, inpatient admission and IV antibiotic therapy remain first-line therapy until further studies investigating doxycycline’s use are performed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Previously presented as poster presentations at ACP U.S. Navy Chapter Scientific Meeting 2020, Portsmouth, VA, and ACP Internal Medicine Meeting 2020, Virtual.

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

- antibiotics

- complete atrioventricular block

- electrocardiogram

- lyme disease

- doxycycline

- heart block

- first degree atrioventricular block

- exercise intolerance

- cardiology

- exercise stress test

- fever

- headache

- exanthema

- follow-up

- infections

- guidelines

- ocular pain

- cardiovascular monitoring

- lyme carditis

- chronotropic agents

- antibiotic therapy, intravenous

- high grade atrioventricular block