-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Conor B Garry, Reginald Middlebrooks, John D Moore, Jason M Souza, Timothy E Sayles, Robert L Ricca, Experience in Providing Ambulatory Surgery From an Expeditionary Fast Transport Mobile and Rapidly Deployable Expeditionary Medical Unit During Continuing Promise 2018, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages e1835–e1841, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usad001

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

This article describes the surgical component of the Continuing Promise 2018 (CP-18) medical training and military cooperation mission. We report on the surgical experience and lessons learned from performing peacetime ambulatory surgeries in a tent-based facility constructed on partner nation territory.

This CP mission was unique in utilizing a land-based expeditionary surgical facility. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to collect prospective deidentified patient data and aggregate information on all surgical cases performed. Specific aims of this study included describing surgical patient characteristics and evaluating conservatively selected cases performed in this environment. Body mass index (BMI) was used as a crude screening tool for perioperative risk to assist patient selection. Our secondary aim was to report lessons learned from preparation, logistics, and host nation exchanges. The team coordinated medical credentialing and documentation of all medical supplies with each host nation. Advance teams collaborated with local physicians in country to arrange training exchanges and identify surgical candidates.

The mission was conducted from February to April 2018. Only two of five planned partner nation visits were completed. The surgical facility supported 78 procedures over 14 surgical days, averaging over six cases performed per core surgical day. Patients were predominantly female, with a mean age of 25.4 and a mean BMI of 31.1. The average surgical time was 37.5 minutes, the average anesthesia time was 70 minutes, and the average recovery time was 47.6 minutes. No significant complications or adverse events were noted.

CP-18 was the first CP mission to perform elective ambulatory surgery on foreign soil using a tent-based facility in a noncombat, nondisaster environment instead of a hospital or amphibious ship. This mission demonstrated that such a facility may be employed to safely perform low-risk ambulatory surgeries on carefully selected patients. The Expeditionary Medical Unit, coupled with the fast transport vessel enabled rapid expeditionary surgical facility setup with significant military and disaster relief applications. Expansion of surgical indications should be performed carefully and deliberately to avoid complications and damage to international relationships.

INTRODUCTION

Continuing Promise (CP) is a U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) area of responsibility training and cooperation mission that was first introduced in 2007. The purpose of CP is to conduct Civil-Military Operations, including medical assistance, in order to build partner nation capacity. CP 2018 was the ninth CP deployment mission, signaling continued U.S. commitment to regional partner nations.1 This is the first CP mission to provide nonemergent peacetime surgical care utilizing military tent-based facilities operating within a foreign nation’s borders. Our objective was to safely perform five ambulatory surgeries per day in this facility to demonstrate that this facility could be used to augment local assets to facilitate training exchanges or provide emergency support. We report lessons learned from the planning and execution of the mission and analyze the general characteristics of the surgeries performed.

METHODS

Concept of Operations

This is an Institutional Review Board (IRB)–approved prospective research protocol evaluating a Surgical Expeditionary Medical Unit (EMU) facility’s ability to safely perform routine low-risk surgeries on carefully selected patients as part of an ongoing health cooperation and training mission. Previous humanitarian mission reports have advised selecting procedures that are minimally invasive, require little follow-up, and provide immediate relief of pain.2 Indication of high-risk surgeries, procedures requiring complicated postoperative management, or surgical indications that exceed the local infrastructure risk causing more harm than good and may adversely affect host nation mission perception. The literature reports that unexpectedly high complication rates are likely while performing complex procedures abroad, especially if surgeons are pressured to operate outside of their comfort zone.3,4 We employed conservative patient selection criteria for minor surgical procedures requiring little to no special equipment or implants. We prioritized short operating times, rapid recoveries, and low risk for blood loss, infection, or surgical complications. We lacked robust patient receiving capacity and planned only ambulatory cases. Patients under 2 years old were excluded. Patients needed to meet same-day surgery criteria and required transportation to home immediately after recovery. Because of high local prevalence, a pre-operative tuberculosis screening questionnaire was completed by each patient and accompanying family member. A chest radiograph was performed when indicated.

We created data sheets to collect anonymized patient identifiers, age, gender, medical history, chief complaint, surgical indication, surgery type, operative time, recovery time, type of anesthesia used, and any record of difficulty or complication. If patients were not surgical candidates, the reasons were documented. Adverse events including mortality, unplanned patient transfer, transfusion requirement, and other surgical or anesthetic complications would be thoroughly documented.

This study was observational. No patients were subjected to experimental treatments, and therefore, no statistical analysis or comparison of characteristics of different patient subgroups was performed apart from percentage reporting based on raw data. We anticipated a study population of 30 surgical patients per country amounting to 150 patients in total. The possibility for selection bias because of channeling of patients by host nation Ministries of Health was acknowledged; however, the study design made this difficult to control because of the need to work within local health systems. We planned to track the number of patients deferred as well as no-shows. Our primary focus was the quality of care delivered. An acknowledged study shortcoming was the lack of long-term follow-up because of the brief nature of each country visit.

All procedures would be performed to the standard or care of the USA. All provider behaviors, including the use of safety checklists, surgical sterility, and anesthesia protocols, were performed to Department of Defense surgical facility standards. All surgical and anesthesia personnel were fully credentialed medical center staff. No residents or trainees participated in patient care. Surgical case logs were organized by the host nation, deidentified, and evaluated after mission completion. We retained no patient identifiable information.

Mission Planning

The mission called for 256 medical personnel to embark a small fast transport ship assigned to ferry them between country visits. It would send the team and equipment ashore to set up a medical clinic site and a surgical facility at locations pre-coordinated with the host nation. The initial plan was to provide medical and surgical care to five Latin American partner countries including Colombia, Panama, Guatemala, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic from January through May 2018.

Predeployment coordination with partner nation stakeholders is fundamental to successful mission planning and execution.3 Miscommunication may cause inefficiency, frustration, and damage to the host nation relationship.2 Accordingly, Advance Coordination Element (ACE) teams engaged the local ministries of health well before the mission to determine surgical needs. After coordinating with our surgeons, they presented our host nation partners with a list of procedures we were comfortable performing. The partner nation then provided a list of surgical candidates. ACE coordination with local hospitals also identified opportunities for Subject Matter Expert exchanges within local health care facilities before deployment.

The pioneering land-based surgical aspect of this mission prompted host nation Ministries of Health to present understandable requirements for verifying medical credentials and documenting all equipment and consumable medical supplies to be brought into their country. Credentialing packages were created for all medical personnel. We inventoried every item brought ashore, totaling 613 discreet medical items, referencing the National Stock Number database to obtain the appropriate 12-digit identifier. This was performed for all five planned country visits and represented a significant investment of time and resources. The mission was delayed several times for reasons including unsuitably rough seas enroute and ship nonavailability because of unscheduled maintenance. The mission leadership responded by shuffling mission stops. Two country visits were canceled as unplanned delays reduced the available mission time. The last scheduled stop was canceled late in the deployment after local factors made the visit impractical.

Predeployment Training

Global health literature identifies insufficient predeployment mission orientation and training as a significant impediment to mission success.5–7 This mission incorporated formal scheduled predeployment training. Most EMU personnel were brought together 2 months before departure for training to include key personnel introductions, country specific briefings, and concept of operations. The EMU staff received hands-on training for setting up, taking down, and repairing the Base-X® tents used to assemble the facility. They also practiced setting up the operating rooms and peri-operative facilities. This team-building experience later proved indispensable. Supervised training in a controlled environment conditioned the team members to build the EMU on mission in half the planned time. Predeployment troubleshooting enabled the surgical team to work with the engineers to modify the tent layout and the internal setup to improve patient workflow and operating room layout. This would have been impractical in theater.

Logistics Support

Historically, CP missions were conducted on a U.S. Navy hospital ship (T-AH) or a large amphibious warship with significant medical capability.8 CP-18 marked the second consecutive year that the mission embarked on the U.S. Naval Ship (USNS) Spearhead (T-EPF-1), a 1,515-ton expeditionary fast transport ship (T-EPF) operated by Military Sealift Command. The USNS Spearhead is an aluminum catamaran vessel derived from a civilian ferry. It has a maximum design speed of 43 knots without payload in calm seas. The mission bay, used to carry cargo, is more than 20,000 ft.2,9 SPEARHEAD has no organic medical facilities apart from a one-room sick bay.

The ship is crewed by 26 civilian mariners. It has sleeping facilities for 104 personnel and has 312 theater style troop seats for use in a ferry role. Underway periods are limited to 3 days or less when several hundred personnel are embarked, as the practice of rotating a single bed among multiple sailors, known as “hot-racking,” becomes necessary. Two hundred fifty-six medical personnel were assigned to this mission in addition to the ship’s company and the embarked Fourth Fleet staff. The ratio of sailors to available beds was approximately 3:1.

Once in country, the ship’s berthing, hygiene, and supply limitations required the medical and support staff conducting CP-18 to establish a field environment ashore. Mission participants established a “tent city” in each mission location including dormitory tents, a cafeteria, shower facilities, and portable toilets. Medical staff traveled daily from the tent facilities to either the surgical EMU or the primary medical work site, where 800 host nation patients per day on average received primary and specialty medical care.

The Expeditionary Medical Unit

The surgical EMU was part of a broader medical mission. Two hundred fifty-six medical staff were assigned to CP, and 42 of these were assigned to the EMU. The EMU synonymized not only the physical facility but also the team assigned to it, who enjoyed significant autonomy and flexibility. Surgical personnel not on the daily operative schedule provided first assist, scheduled subject matter exchanges at local hospitals, performed training, or directly supported the medical mission.

Mission planning called for ten surgeons, four anesthesiologists, and four Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs). Competing requirements reduced the surgical complement considerably. Final surgical staffing included seven surgeons, one anesthesiologist, two CRNAs, 10 nurses, an emergency medicine doctor, a radiologist, a clinical pharmacist, and 19 hospital corpsmen. The surgical specialists included a colorectal surgeon, a pediatric surgeon, an orthopedic surgeon, one obstetrician, an oral surgeon, a plastic surgeon, and a urologist. Specialists in radiology, obstetrics and gynecology, orthopedics, and emergency medicine often assisted the medical component of the mission off-site.

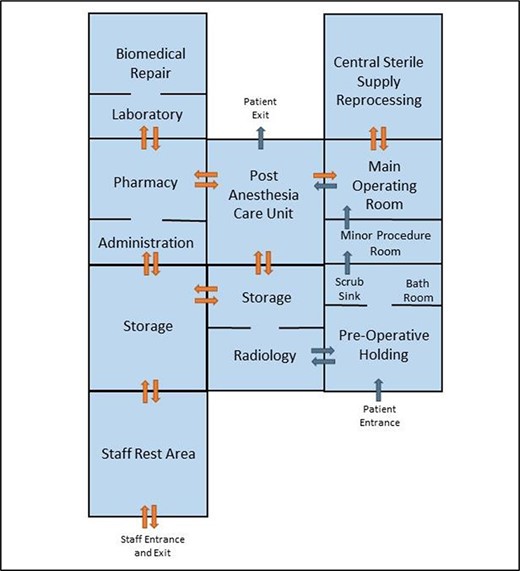

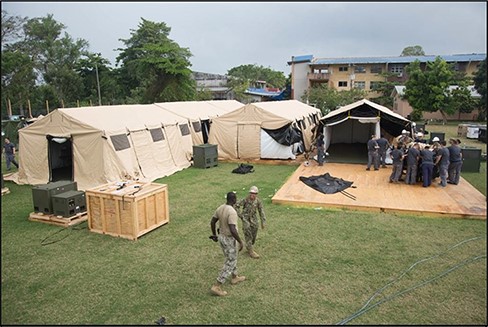

The EMU facility consisted of nine Base-X® tents that were assembled to form a single self-contained ambulatory surgery facility (see Figs. 1 and 2) built atop a plywood platform to ensure a stable level surface for operating room equipment. The predeployment objectives were to successfully construct a rapidly deployable medical facility, implement thorough preoperative screening, perform five low-risk ambulatory surgeries a day, and provide limited postoperative recovery. Each mission stop lasted 16 days. This was divided into the following segments: days 1-3: hospital setup, days 4-5: patient evaluation and preoperative screening, days 6-10 and 12-14 surgical days, day 11 for rest, and days 15-16: facility takedown.

RESULTS

Description of Surgical Cases

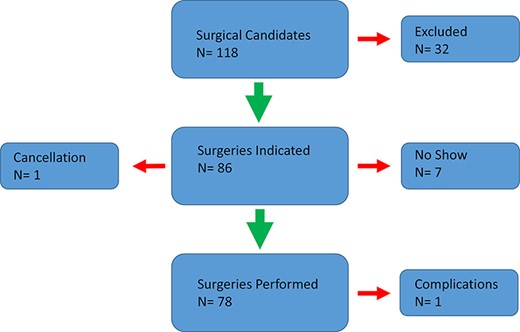

ACE team coordination with the host nation accounted for most operative cases. Medical site referrals also provided suitable surgical candidates. Using the facilities depicted in Figure 3, we performed 78 surgeries and procedures in two countries. There were 19 general surgeries, 9 orthopedic surgeries, 6 urologic surgeries, 25 oral surgeries, 13 surgeries performed by the plastic surgeon, and 4 gynecologic procedures. Additionally, two procedures were performed in the EMU by the dermatologist who had requested plastic surgery support. Surgical cases ranged in complexity from a reverse sural flap with split thickness skin grafting and hernia repairs on the complex side to the more straightforward closed joint and fracture reductions under anesthesia and dental extractions. Refer Table S1 for a list of specific procedures performed.

Combined plastic surgery and urology case in the main operating room.

General, regional, neuraxial, and monitored anesthesia care and local anesthetics were administered without significant event. The mean patient age was 24 years old, and the mean Body mass index was 31.1. The average surgery time was 39 minutes (range 8-96 minutes). The mean recovery time was 32 minutes (range 0-180 minutes). One complication was reported involving a prolonged anesthesia emergence requiring transfer to a local facility for monitoring. The flow diagram to include exclusions, cancellations, and no-shows is available in Figure 4.

Field experience is heavily emphasized in humanitarian literature, and during our mission, its importance was redemonstrated.10 On deployment, seemingly simple changes in tent orientation suggested by senior nurses and doctors would require painstaking reconstruction of the electrical grid and relocation of supporting external equipment, including generators and ventilation systems. Modified early, these changes were field tested before deployment. Two of the surgical tents, which could be partitioned into three equal units, were altered to expand the facility’s capacity. The team created a primary and secondary operating theater, using one-third of the operative tent for minor procedures and two-thirds for more complex procedures requiring general anesthesia. We set aside one-third of our pre-operative tent for lavatory facilities. The pre-operative area had four patient beds, and this was adequate in our experience. We averaged 6.2 and 6.5 patients per core surgical day in Guatemala and Honduras, respectively. A mean of 1.9 surgical patients were treated in the smaller operating room, corresponding to 30% of total operative output. The mission easily exceeded the surgical throughput goal of five patients per day without any safety concerns. Table S1 describes the cases, specialty, type of anesthetic, surgical time, complications, etc. Table S2 describes patient characteristics.

Subject Matter Expert Exchanges

The ACE team organized Subject Matter Expert Exchanges (SMEEs) to engage host nation medical personnel. The SMEEs varied from casual conversation to coordination among operating room staff regarding complex surgical cases. There were many examples of successful professional interactions. At a local hospital, the surgeons hesitated to use a skin-grafting device (dermatome) because they had not received appropriate training. Instead, they used a razor blade and mineral oil. Our plastic surgeon a demonstrated proper dermatome technique, provided hands-on training, and thus expanded the health care system’s capacity to provide this treatment. Otherwise, this patient would have had to travel an hour away to an urban trauma center for care. Another example of capacity building was the collaboration of several members of the EMU with partner nation surgical staff to remove a large facial plexiform neurofibroma from a male adolescent patient.11 Host nation doctors and other medical personnel were scrubbed in and working with their U.S. counterparts. This international learning effort was documented and published in print media and electronically by Navy public affairs specialists.12,13

The variability of operating room and intensive care equipment compared to U.S. military hospitals presented challenges. Host nation equipment resources were infrequently standardized and were typically sourced from multiple different nations with manuals rarely provided in Spanish. This created challenges for host nation providers to operate this equipment and made it virtually impossible to keep everything functioning properly. This is a common challenge in similar medical systems and is a recognized obstacle to the efficient provision of surgical care.14 Reports place the percentage of inoperable equipment at approximately 40%, with leading reasons being cost, complexity, and lack of spare parts.15 Working together with host nation counterparts, our biomedical technicians were able to troubleshoot critical equipment such as fluoroscopes and anesthesia machines. They returned several pieces of equipment to service, and identified specific parts would be needed if an immediate repair was not possible. This contributed materially to host nation training as well as medical capacity.

CONCLUSION

Key Findings

Effective predeployment planning and training allowed the team to determine host nation need, patient flow, and roles and responsibilities before arriving in country. It also provided the team with construction experience, which saved valuable time during the mission. Our surgical case selection was conservative, but there were valuable lessons learned. Preoperative anesthesia evaluation and scheduling of all surgical patients may improve patient selection and avoid unwanted adverse effects. Staff redundancy was beneficial in many aspects of perioperative patient care. Although the EMU deployed with a reduced surgical and anesthesia footprint, we assess no significant impact on case volume. Mission personnel consistently engaged partner nation hospitals, and further staffing would have added little to these exchanges.

The CP-18 EMU successfully performed both minor and low-risk major surgeries in a nine-tent field hospital in two separate nations with minimal setup and takedown time with transportation provided by an inexpensive expeditionary fast transport. Increased confidence and efficiency were evident in setting up the hospital and coordinating surgical equipment in Guatemala, the second nation visited. The ability to perform more complex surgeries within the EMU could be easily executed with the appropriate equipment and supplies. This capacity to provide flexible and mobile surgical capabilities ashore may prove valuable when evacuating patients to a traditional facility is not a practical or sustainable option, whether in response to national disaster or in support of dynamic military operations in future conflicts.

Future Directions

Further missions may benefit from more technically advanced and minimally invasive procedures and equipment. Partner nation doctors consistently requested we provide equipment and training for arthroscopy, endoscopy, hysteroscopy, and cystoscopy. This presents opportunities for future missions as military surgeons have significant experience in these areas. Cooperation extended beyond the surgical suite. Our maintenance personnel expanded capacity by improving the infrastructure itself, and our hosts were greatly appreciative of their efforts.

Several partner nation surgeons desired longer mission stops and felt that by the time relationships were starting to form, the country visit was over. Such views can lead to the perception of “medical tourism” often derided in global health engagement literature.16 Longer mission times could cultivate deeper ties between partner nation civilian medical leadership and U.S. military medical professionals.

On such missions, the military medical team’s priorities are often contrary to the mission’s diplomatic goals, which may prioritize “showing the flag” throughout a wide region over more meaningful, long-term medical engagement in a narrower geographic area.2 This is apparent to regional partners as well as critics and potential adversaries.2,17 The need for more in-depth engagement is well known and has been strongly argued since at least CP 2011.18 Proposed remedies include promoting surgical staff participation in Global Health Engagement, encouraging staff continuity of these missions, and sending smaller teams periodically outside of the formal mission framework to sustain relationships and provide meaningful assistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Clarence Tang for his photographic contribution.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at Military Medicine online.

FUNDING

None declared.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION: IDENTIFIER:

Not applicable.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD (HUMAN SUBJECTS)

This study was approved Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (NMCP) IRB (NMCP 2018-0034).

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC)

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

INDIVIDUAL AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

R.L.R. and J.D.M. designed the study and then drafted and submitted the IRB. Following this, they provided continuous guidance and oversight. C.B.G. and R.M. collected and analyzed the data and drafted the original manuscript. J.M.S., and T.E.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript and assisted in securing figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Raw data were generated at the EMU while on deployment. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

INSTITUTIONAL CLEARANCE

Institutional clearance approved.

REFERENCES

Author notes

(1) Podium: Society of Military Orthopaedic Surgeons Annual Meeting. December 2018, Keystone, CO.

(2) Podium: NMRTC Camp Lejeune Operational Medicine Conference. June 2022, Jacksonville, NC.

The views expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense, or the Department of the Navy.