-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sara B Mullaney, Heather Bayko, Gerald D Moore, Hannah E Funke, Matthew J Enroth, Derron A Alves, The Veterinary Treatment Facility as a Readiness Platform for Veterinary Corps Officers, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages e1367–e1375, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usab240

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

U.S. Army Veterinary Corps provides highly skilled and adaptive veterinary professionals to protect and improve the health of people and animals while enhancing readiness throughout the DOD. Army veterinarians must be trained and credentialed for critical tasks within the animal health and food protection missions across all components. The Veterinary Metrics Division in the U.S. Army Public Health Center’s Veterinary Services and Public Health Sanitation Directorate is responsible for tracking readiness metrics of Army veterinarians and maintains a robust online Readiness Metrics Platform. Readiness targets were developed based on trends in readiness platform data, input of senior veterinary subject matter experts, and feedback from the field. To date, no data have been published describing the cases presented to DOD-owned Veterinary Treatment Facilities (VTFs). Without capturing and codifying the types of cases that present to the VTF and comparing to cases typically encountered during deployments, it is difficult to determine whether the VTF serves as an adequate readiness platform. In this study, we compare a representative random sample of non-wellness VTF patient encounters in garrison to cases reported from two different combat zones to determine if the VTF is a suitable clinical readiness platform.

Multiple data sources, including pre-existing published data and new data extracted from multiple sources, were used. The Iraq 2009-2010 dataset includes data collected from a Medical Detachment, Veterinary Service Support (MDVSS) deployed to Iraq from January 5, 2009 through August 23, 2010. The Iraq 2003-2007 dataset originated from a retrospective cross-sectional survey that included database and medical record abstraction. The Afghanistan 2014-2015 dataset includes data collected from the MDVSS deployed to Afghanistan from June 2014 to March 2015. Working dog veterinary encounter data were manually extracted from monthly and daily clinical reports. Data for the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset were extracted from the Remote Online Veterinary Record. A random representative sample of government-owned animal (GOA) and privately owned animal (POA) encounters seen across all DOD-owned VTFs from June 2016 to May 2018 were selected.

We found that animals present to the VTF for a wide variety of illnesses. Overall, the top 10 encounter categories (90.3%) align with 84.2%, 92.4%, and 85.9% of all the encounter types seen in the three combat zone datasets. Comparing these datasets identifies potential gaps in readiness training relying solely on the VTF, especially in the areas of traumatic and combat-related injuries.

Ultimately, the success of the DOD Veterinary Services Animal Health mission depends on both the competence and confidence of the individual Army veterinarian. As the MHS transitions and DOD Veterinary Services continues to transform emphasizing readiness through a public health and prevention-based Army medicine approach, Army veterinarians must strike a delicate balance to continue to provide comprehensive health care to GOAs and POAs in the VTFs. Leaders at all levels must recognize the roles VTFs play in overall public health readiness and disease prevention through the proper appropriation and allocation of resources while fostering the development, confidence, and competence of Army veterinarians training within these readiness platforms.

INTRODUCTION

U.S. Army Veterinary Corps provides highly skilled and adaptive veterinary professionals to protect and improve the health of people and animals while enhancing readiness throughout the DOD.1 Veterinary Corps Officers (VCOs), consisting of U.S. Army veterinarians and food safety warrant officers, must be trained and credentialed for critical tasks within the animal health and food protection missions across all components.1 Although VCOs encompass food safety warrant officers, this manuscript is relevant to Army veterinarians (i.e., Doctors of Veterinary Medicine or Veterinary Medical Doctors) who are graduates from an American Veterinary Medical Association accredited veterinary school in the USA, Puerto Rico, or Foreign Countries, providing they possess a permanent certificate from the Educational Commission for Foreign Veterinary Graduates. The Veterinary Metrics Division in the U.S. Army Public Health Center’s Veterinary Services and Public Health Sanitation Directorate is responsible for tracking readiness metrics of Army veterinarians and maintains a robust Readiness Metrics Platform on the Defense Health Agency’s carepoint.health.mil website.2 The current readiness targets were developed based on trends in readiness platform data, input of senior veterinary subject matter experts, and feedback from the field to provide commanders and leaders with sound objective data so they can assess readiness and optimize the support provided by U.S. Army Veterinary Services within their respective areas of responsibility.1

The animal health readiness metrics are a proxy to measure whether individual Army veterinarians are trained and are maintaining the skillsets necessary to provide comprehensive medical and surgical care to military working dogs (MWDs) serving in contingency and/or forward-deployed operations. DOD-owned Veterinary Treatment Facilities (VTFs) are the primary location where practicing Army veterinarians receive hands-on experience in assessing, diagnosing, and treating illness and injury in companion animals. As such, the VTFs currently serve as the primary clinical readiness platform to train Army veterinarians (and enlisted animal care specialists), and clinical VTF data are the source for clinical readiness metrics. The majority of Army veterinarians who deploy in support of contingency and battlefield operations and provide comprehensive medical and surgical care of MWDs are generally recent veterinary school graduates, having 3 or less years of clinical experience.3 While assigned to 1 of the 135 globally distributed garrison VTFs, Army veterinarians gain exposure to companion animal medical and surgical cases in preparation for combat-related and noncombat-related injuries and illness they would expect to face during deployment. The current clinical readiness targets for Army veterinarians focus on meeting a quota of different encounter categories: routine wellness cases, non-wellness cases (“sick call”), surgical procedures, and dental procedures.1 There is no requirement for a specific encounter type to maintain readiness. To date, no data have been published describing the cases presented to DOD-owned VTFs. Without capturing and codifying types of cases that present to the VTF and comparing to cases typically encountered during deployments, it is difficult to determine whether the VTF serves as an adequate readiness platform.

Military working dogs serving in combat operations are force multipliers and perform various duties and functions ranging from the detection of drugs and explosives to scent tracking and general patrol.3–5 Although there are previous reports that describe combat-related and noncombat-related injuries, illness, and deaths among MWDs in combat zones, as well as limited reports that describe medical care of the MWD in combat zones, additional studies are needed to determine whether the reasons for veterinary visits for deployed MWDs are similar to the reasons for dog veterinary visits at DOD-owned VTFs on garrison installations.3,5–11 In this study, we compare a representative random sample of non-wellness VTF patient encounters in garrison to cases reported from two different combat zones (i.e., Iraq and Afghanistan) to determine if the VTF is a suitable readiness platform for Army veterinarians and animal care specialists. Ultimately, these data can inform specific readiness targets and help determine whether additional training beyond the VTF may be required to maintain clinical veterinary readiness.

METHODS

Multiple data sources including pre-existing published data and new data extracted from multiple sources were used. These datasets will be referred to as follows: Garrison 2016-2018, Iraq 2003-2007, Iraq 2009-2010, and Afghanistan 2014-2015. The Iraq 2009-2010 dataset was provided by Dr. Matt Takara (LTC retired, US Army Veterinary Corps) and includes data collected from a Medical Detachment, Veterinary Service Support (MDVSS) deployed to Iraq from January 5, 2009 through August 23, 2010. The methodology and categorization of these data were previously published.3

The Iraq 2003-2007 dataset was provided by Dr. Wendy Mey (LTC retired, U.S. Army Veterinary Corps) and is a retrospective cross-sectional survey based on database and medical record abstraction.12 The population of interest includes 795 MWDs deployed to Iraq from March 2003-December 2007.12 To allow for comparison in the present study, the raw data were re-categorized into the same 19 primary encounter categories and subcategories as the Iraq 2009-2010 data.

The Afghanistan 2014-2015 dataset includes data collected from the MDVSS deployed to Afghanistan from June 2014 to March 2015. Working dog veterinary encounter data were manually extracted from monthly and daily clinical reports. The data were categorized into the same 19 primary encounter categories and sub-categories as the Iraq 2009-2010 data. Once all working dog clinical encounters were categorized, the same exclusion criteria as the Takara study were applied.

Data for the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset were extracted from the Remote Online Veterinary Record (ROVR), the electronic veterinary medical record-keeping system for garrison DOD-owned VTFs. A random representative sample of government-owned animal (GOA, i.e., animals owned by Federal Government entities includes MWDs among others) and privately owned animal (POA, i.e., pets owned by service members and/or eligible DOD beneficiaries) encounters seen across all DOD-owned VTFs from June 2016 to May 2018 were selected. All electronic medical note (eNote) lists during the time period of interest for all GOA and POA encounters at DOD-owned VTFs worldwide, excluding all non-clinical notes (eNote Titles including draft, veterinary technician, and administrative notes), were exported. Once eNote lists were downloaded, additional exclusion criteria were applied to remove additional non-clinical eNotes and wellness-only appointments. The final eNote lists were collated into single geographic region files based on the four Public Health Commands and 14 Public Health Activities within the U.S. Army Medical Command and, then, separated by corresponding Public Health Activity and patient type (GOA or POA). Each eNote was assigned a random number by Public Health Activity for priority of selection. Because of the manpower required to download individual eNotes and manually categorize the record, the number of records to download was minimized while still maximizing the power of the study. For GOA eNotes, the minimum sample size was set to equal that of the Iraq 2009-2010 data study (n = 1350). The Iraq 2009-2010 study dataset had a larger sample size than the Iraq 2003-2007 data, and 20% was added (n = 1620) to account for eNotes that may not have been appropriately excluded during the initial scrub. To ensure this sample size was also large enough to be representative of the population of GOA encounters seen in the garrison VTFs, a query was raised to determine all non-wellness GOA encounters seen during the time period covered (n = 5,044) and sample size calculations were performed using the online application OpenEpi Version 3.01. The module calculates the sample size needed to determine the frequency of a given factor in a population at a specific confidence level. The sample size needed to detect a 1% frequency ±0.5% in a population of 5,044 with 95% CI was 1,169. This confirmed that the sample size of 1,620 should be a large enough random sample to represent all MWD non-wellness encounters. We used proportional allocation to select eNotes based on the percentage of total non-wellness MWD encounters per geographic region to ensure an equal probability of selection for each eNote. Using the same approach for POA encounters (n = 106,600, 1.0% frequency, ±0.5%, 95% CI), 1,500 POA records plus an additional 20% were randomly selected for a sample size of 1,800 eNotes. Proportional allocation was used to ensure equal probability of selection for each POA eNote.

Once the individual eNotes were selected, the eNotes were manually downloaded from the ROVR and embedded into an internal data abstraction tool to aid in categorizing each encounter. For the MWD encounters, only MWDs who were in deployment category (CAT) I or CAT II status prior and up to their encounter date were included in the study. This ensured CAT III and CAT IV MWDs (i.e., not deployable) were not over-represented in the resultant sample. Once all eNotes were embedded into the abstraction tool, a single veterinarian categorized each encounter using the same categories and subcategories as the Iraq 2009-2010 data. All same-day or emergent encounters were annotated and categorized as “emergent” once verified. Each eNote was opened and reviewed, and a primary encounter category was chosen based on the main body system affected, as well as the primary clinical sign or stated diagnosis. If more than one diagnosis was made or more than one procedure performed, then an additional entry was made for the same patient.

All data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel Version 2011 and SAS Studio Release 3.8. Each primary encounter category and subcategory for the datasets was expressed as a percentage of total patient encounters and encounters in each assigned category. Comparisons were made between the primary encounter categories across all datasets. Point estimates and 95%CIs were calculated for the Garrison dataset. Chi-square analysis was used to determine if there was a difference in proportion among the same primary encounter categories across the different datasets. A P-value of >.05 was selected to indicate no difference in proportion for the same primary encounter category. Initial analysis excluded combat-related injuries. In a separate analysis, the proportion of non-wellness encounters considered to be combat related was compared across datasets. For the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset, cases marked and verified as emergent served as a proxy for combat related. This analysis was performed separately because of the nature of the original datasets and exclusion criteria established in those studies. We were unable to incorporate these excluded combat-related data back into the noncombat-related encounter data.

RESULTS

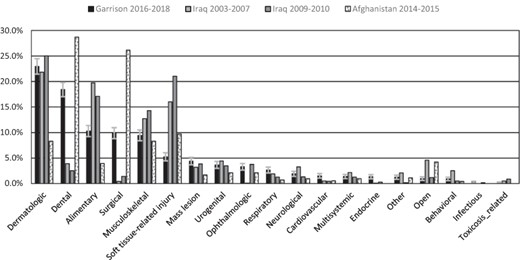

For the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset, 3,521 eNotes were initially randomly selected for inclusion. Of these, 547 were excluded from analysis (203 for CAT III, 109 for CAT IV status, 31 not enough information to categorize, 27 GOAs of non-canine species, 66 rechecks, 84 physical exams, and 27 wellness services). The remaining 2,974 eNotes (GOA, n = 1219; POA, n = 1755) were included in the analysis. In order, the most common primary encounter categories included dermatologic conditions (23.0% [95% CI: 21.5-24.5]), dental encounters (18.4% [95% CI: 17.0-19.8]), alimentary system issues (10.3% [95% CI: 9.2-11.4]), surgical encounters (9.9% [95% CI: 8.8-11.0]), musculoskeletal injuries (9.4% [95% CI: 8.4-10.5]), soft tissue-related injuries (5.2% [95% CI: 4.4-6.1]), and mass lesions (4.4% [95% CI: 3.7-5.1]) (Table I), accounting for 80.7% (95% CI: 79.2-82.1) of all non-wellness encounters.

Clinical Non-wellness Encounters Categorized by Primary Encounter Type and Dataset

| Dataset . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary encounter category . | Garrison 2016-2018 (n = 2974), n (%: 95% CI) . | Iraq 2003-2007 (n = 1,155), n (%) . | Iraq 2009-2010 (n = 1,350), n (%) . | Afghanistan 2014-2015 (n = 711), n (%) . |

| Dermatologic | 683 (23.0: 21.5-24.5) | 252 (21.8) | 338 (25.0) | 59 (8.3) |

| Dental | 548 (18.4: 17.0-19.8) | 45 (3.9) | 34 (2.5) | 204 (28.7) |

| Alimentary | 306 (10.3: 9.2-11.4) | 228 (19.7) | 231 (17.1) | 28 (3.9) |

| Surgical | 294 (9.9: 8.8-11.0) | 5 (0.4) | 19 (1.4) | 186 (26.2) |

| Musculoskeletal | 281 (9.4: 8.4-10.5) | 147 (12.7) | 193 (14.3) | 59 (8.3) |

| Soft tissue-related injury | 156 (5.2: 4.4-6.1) | 185 (16.0) | 284 (21.0) | 69 (9.7) |

| Mass lesion | 131 (4.4: 3.7-5.1) | 37 (3.2) | 52 (3.9) | 12 (1.7) |

| Urogenital | 109 (3.7: 3-4.3) | 51 (4.4) | 47 (3.5) | 15 (2.1) |

| Ophthalmologic | 98 (3.3: 2.7-3.9) | 1 (0.1) | 51 (3.8) | 15 (2.1) |

| Respiratory | 79 (2.7: 2.1-3.2) | 22 (1.9) | 17 (1.3) | 5 (0.7) |

| Neurological | 57 (1.9: 1.4-2.4) | 38 (3.3) | 18 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 45 (1.5: 1.1-2) | 6 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) |

| Multisystemic | 41 (1.4: 1-1.8) | 25 (2.2) | 17 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Endocrine | 40 (1.3: 0.9-1.8) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 37 (1.2: 0.9-1.6) | 24 (2.1) | 2 (0.1) | 8 (1.1) |

| Open | 29 (1: 0.6-1.3) | 53 (4.6) | 16 (1.2) | 30 (4.2) |

| Behavioral | 27 (0.9: 0.6-1.3) | 29 (2.5) | 7 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Infectious | 8 (0.3: 0.1-0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Toxicosis related | 5 (0.2: 0.0-0.3) | 6 (0.5) | 12 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dataset . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary encounter category . | Garrison 2016-2018 (n = 2974), n (%: 95% CI) . | Iraq 2003-2007 (n = 1,155), n (%) . | Iraq 2009-2010 (n = 1,350), n (%) . | Afghanistan 2014-2015 (n = 711), n (%) . |

| Dermatologic | 683 (23.0: 21.5-24.5) | 252 (21.8) | 338 (25.0) | 59 (8.3) |

| Dental | 548 (18.4: 17.0-19.8) | 45 (3.9) | 34 (2.5) | 204 (28.7) |

| Alimentary | 306 (10.3: 9.2-11.4) | 228 (19.7) | 231 (17.1) | 28 (3.9) |

| Surgical | 294 (9.9: 8.8-11.0) | 5 (0.4) | 19 (1.4) | 186 (26.2) |

| Musculoskeletal | 281 (9.4: 8.4-10.5) | 147 (12.7) | 193 (14.3) | 59 (8.3) |

| Soft tissue-related injury | 156 (5.2: 4.4-6.1) | 185 (16.0) | 284 (21.0) | 69 (9.7) |

| Mass lesion | 131 (4.4: 3.7-5.1) | 37 (3.2) | 52 (3.9) | 12 (1.7) |

| Urogenital | 109 (3.7: 3-4.3) | 51 (4.4) | 47 (3.5) | 15 (2.1) |

| Ophthalmologic | 98 (3.3: 2.7-3.9) | 1 (0.1) | 51 (3.8) | 15 (2.1) |

| Respiratory | 79 (2.7: 2.1-3.2) | 22 (1.9) | 17 (1.3) | 5 (0.7) |

| Neurological | 57 (1.9: 1.4-2.4) | 38 (3.3) | 18 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 45 (1.5: 1.1-2) | 6 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) |

| Multisystemic | 41 (1.4: 1-1.8) | 25 (2.2) | 17 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Endocrine | 40 (1.3: 0.9-1.8) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 37 (1.2: 0.9-1.6) | 24 (2.1) | 2 (0.1) | 8 (1.1) |

| Open | 29 (1: 0.6-1.3) | 53 (4.6) | 16 (1.2) | 30 (4.2) |

| Behavioral | 27 (0.9: 0.6-1.3) | 29 (2.5) | 7 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Infectious | 8 (0.3: 0.1-0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Toxicosis related | 5 (0.2: 0.0-0.3) | 6 (0.5) | 12 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

Clinical Non-wellness Encounters Categorized by Primary Encounter Type and Dataset

| Dataset . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary encounter category . | Garrison 2016-2018 (n = 2974), n (%: 95% CI) . | Iraq 2003-2007 (n = 1,155), n (%) . | Iraq 2009-2010 (n = 1,350), n (%) . | Afghanistan 2014-2015 (n = 711), n (%) . |

| Dermatologic | 683 (23.0: 21.5-24.5) | 252 (21.8) | 338 (25.0) | 59 (8.3) |

| Dental | 548 (18.4: 17.0-19.8) | 45 (3.9) | 34 (2.5) | 204 (28.7) |

| Alimentary | 306 (10.3: 9.2-11.4) | 228 (19.7) | 231 (17.1) | 28 (3.9) |

| Surgical | 294 (9.9: 8.8-11.0) | 5 (0.4) | 19 (1.4) | 186 (26.2) |

| Musculoskeletal | 281 (9.4: 8.4-10.5) | 147 (12.7) | 193 (14.3) | 59 (8.3) |

| Soft tissue-related injury | 156 (5.2: 4.4-6.1) | 185 (16.0) | 284 (21.0) | 69 (9.7) |

| Mass lesion | 131 (4.4: 3.7-5.1) | 37 (3.2) | 52 (3.9) | 12 (1.7) |

| Urogenital | 109 (3.7: 3-4.3) | 51 (4.4) | 47 (3.5) | 15 (2.1) |

| Ophthalmologic | 98 (3.3: 2.7-3.9) | 1 (0.1) | 51 (3.8) | 15 (2.1) |

| Respiratory | 79 (2.7: 2.1-3.2) | 22 (1.9) | 17 (1.3) | 5 (0.7) |

| Neurological | 57 (1.9: 1.4-2.4) | 38 (3.3) | 18 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 45 (1.5: 1.1-2) | 6 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) |

| Multisystemic | 41 (1.4: 1-1.8) | 25 (2.2) | 17 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Endocrine | 40 (1.3: 0.9-1.8) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 37 (1.2: 0.9-1.6) | 24 (2.1) | 2 (0.1) | 8 (1.1) |

| Open | 29 (1: 0.6-1.3) | 53 (4.6) | 16 (1.2) | 30 (4.2) |

| Behavioral | 27 (0.9: 0.6-1.3) | 29 (2.5) | 7 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Infectious | 8 (0.3: 0.1-0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Toxicosis related | 5 (0.2: 0.0-0.3) | 6 (0.5) | 12 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dataset . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary encounter category . | Garrison 2016-2018 (n = 2974), n (%: 95% CI) . | Iraq 2003-2007 (n = 1,155), n (%) . | Iraq 2009-2010 (n = 1,350), n (%) . | Afghanistan 2014-2015 (n = 711), n (%) . |

| Dermatologic | 683 (23.0: 21.5-24.5) | 252 (21.8) | 338 (25.0) | 59 (8.3) |

| Dental | 548 (18.4: 17.0-19.8) | 45 (3.9) | 34 (2.5) | 204 (28.7) |

| Alimentary | 306 (10.3: 9.2-11.4) | 228 (19.7) | 231 (17.1) | 28 (3.9) |

| Surgical | 294 (9.9: 8.8-11.0) | 5 (0.4) | 19 (1.4) | 186 (26.2) |

| Musculoskeletal | 281 (9.4: 8.4-10.5) | 147 (12.7) | 193 (14.3) | 59 (8.3) |

| Soft tissue-related injury | 156 (5.2: 4.4-6.1) | 185 (16.0) | 284 (21.0) | 69 (9.7) |

| Mass lesion | 131 (4.4: 3.7-5.1) | 37 (3.2) | 52 (3.9) | 12 (1.7) |

| Urogenital | 109 (3.7: 3-4.3) | 51 (4.4) | 47 (3.5) | 15 (2.1) |

| Ophthalmologic | 98 (3.3: 2.7-3.9) | 1 (0.1) | 51 (3.8) | 15 (2.1) |

| Respiratory | 79 (2.7: 2.1-3.2) | 22 (1.9) | 17 (1.3) | 5 (0.7) |

| Neurological | 57 (1.9: 1.4-2.4) | 38 (3.3) | 18 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 45 (1.5: 1.1-2) | 6 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) |

| Multisystemic | 41 (1.4: 1-1.8) | 25 (2.2) | 17 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) |

| Endocrine | 40 (1.3: 0.9-1.8) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 37 (1.2: 0.9-1.6) | 24 (2.1) | 2 (0.1) | 8 (1.1) |

| Open | 29 (1: 0.6-1.3) | 53 (4.6) | 16 (1.2) | 30 (4.2) |

| Behavioral | 27 (0.9: 0.6-1.3) | 29 (2.5) | 7 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Infectious | 8 (0.3: 0.1-0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Toxicosis related | 5 (0.2: 0.0-0.3) | 6 (0.5) | 12 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

Of the dermatologic causes for presentation, the most common causes were otitis externa (29.4% [95% CI: 26.0-32.85]), dermatitis (20.8% [95% CI: 17.8-23.8), atopic dermatitis (11.6% [95% CI: 9.2-14.0]), and acute moist dermatitis (4.7% [95% CI: 3.1-6.3]). Otitis externa was attributed to infections caused by mixed pathogens (28.9% [22.6-35.1]), yeast (22.9% [95% CI: 17.1-38.7]), and bacteria (10.0% [95% CI: 5.8-14.1). Dermatologic conditions associated with >1% of patient encounters included other, generalized superficial pyoderma, pododermatitis, sebaceous cyst, alopecia, abscess, scrotal dermatitis, acral lick granuloma, insect bite, hygroma, and aural hematoma. Less than 1% of encounters were because of demodicosis, flea allergy, skin tag, lick granuloma, immune-mediate with cutaneous manifestations, seborrhea, facial swelling, nasal hyperkeratosis, or folliculitis.

The four most encountered dental-related conditions were dental prophylaxis (60.4% [95% CI: 56.3-64.5]), extraction (22.3% [95% CI: 22.3-18.8]), fractured/broken teeth (6.9% [95% CI: 4.8-9.1]), and periodontal disease (3.3% [95% CI:1.8-4.8]). The most extracted teeth were incisors (43.4% [95% CI: 34.7-52.2]), followed by molars (23.0% [95% CI:15.5-30.4]), canines (18.9% [95% CI: 11.9-25.8]), and premolars (11.5% [95% CI: 5.8-17.1]). There were four extractions where the extracted tooth was not identified. Of the 15 periodontal disease encounters receiving a grade, seven were graded III/IV, four were graded IV/IV, three were graded II/VI, and one was graded I/IV. The only dental-related condition associated with >1.0% of patient encounters included root canal, all of which were performed on canine teeth. Less than 1% of dental-related encounters included (in order) other, tooth abscess, gingivitis, discoloration, healthy, receding gingiva, severe tartar, exposed root, and loose tooth.

The four most common alimentary causes for presentation were diarrhea (29.4% [95% CI (24.31-34.52]), vomiting (20.6% [95% CI: 16.06-25.12)]), diarrhea and vomiting (11.4% [95% CI: 7.87-15.00]), and other (9.2% [95% CI: 5.92-12.38]). Diarrhea encounters were categorized as non-bloody (68.9 [95% CI: 59.33-78.45), bloody (21.1% [12.68-29.54)), or not differentiated (10.0% [95% CI: 3.8-16.2]). Alimentary conditions classified as other included non-dental oral conditions, gastric dilatation, preparation for colonoscopy, and anal conditions that did not fit the anal glad impaction or abscess categories. Other alimentary-related conditions associated with >1.0% of encounters included hematochezia, gastrointestinal parasites, gastrointestinal foreign body, anal gland impaction, constipation, anal gland abscess, and weight loss. Less than 1% of alimentary-related encounters included hernias (umbilical or perineal) tongue injury, acute abdominal pain, anorexia, and sialocele.

The four most common surgical causes for presentation were castration (27.6% [95% CI: 22.4-32.7]), mass removal (21.1% [95% CI: 16.4-25.8]), ovariohysterectomy (20.1% [95% CI: 15.5-24.7]), and other (9.9% [95% CI: 6.5-13.3]). Surgical conditions associated with >1.0% of encounters included caudectomy, prophylactic gastropexy, castration with scrotal ablation, wound repair, and dehiscence repair.

In order, the most common primary encounter categories in the Iraq 2003-2007 dataset were dermatologic, alimentary, soft tissue-related injury, musculoskeletal, and open (Table I), accounting for 74.9% of all non-wellness encounters.

In order, the most common primary encounter categories in the Iraq 2009-2010 dataset were dermatologic, soft tissue-related injury, alimentary, musculoskeletal, and mass lesion (Table I), accounting for 81.3% of all non-wellness encounters.

The Afghanistan 2014-2015 dataset initially contained 1,882 encounters, but 1,170 encounters were excluded from analysis (82 unable to be categorized, 481 recheck exams, 357 physical exams, 24 combat-related injury, and 227 wellness services). In regard to the remaining 711 included in analysis, the most common primary encounter categories (in order) were dental, surgical, soft tissue-related injury, dermatologic, and musculoskeletal (Table I), accounting for 81.2% of all non-wellness encounters.

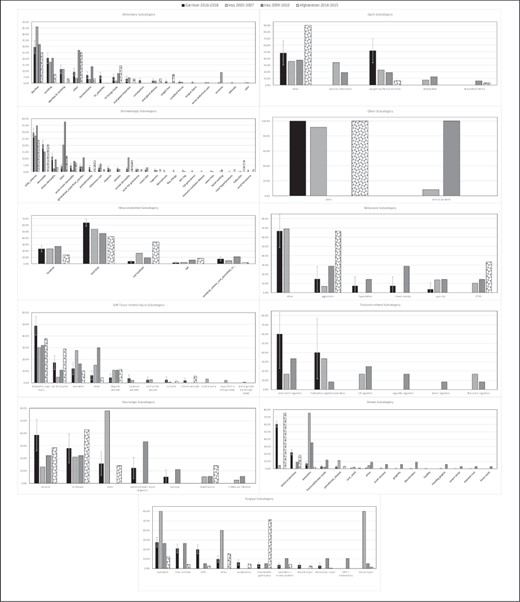

There were multiple primary encounter categories where the proportion of encounters were greater in the combat datasets than the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset (Fig. 1). For the Iraq 2003-2007 dataset, this includes alimentary (diarrhea and anorexia), musculoskeletal (not localized), soft tissue-related injuries (laceration-not footpad or paw and dog bite wounds), neurological (other and head trauma), other (vehicle accident-dog in vehicle), open (exercise intolerance, dehydration, and dependent edema), behavioral (travel anxiety, gun shy, and PTSD), and toxicosis related (C4 ingestion and flea collar ingestion) (Fig. 2). In the Iraq 2009-2010 dataset, this includes alimentary (other, hematochezia, and gastrointestinal foreign body), dermatologic (otitis externa, other, acute moist dermatitis, and generalized superficial pyoderma), musculoskeletal (not localized), and soft tissue-related injury (other) (Fig. 2). For the Afghanistan 2014-2015 dataset, this includes dental (prophylaxis), surgical (prophylactic gastropexy), soft tissue-related injuries (tail tip trauma, dog bite wounds, and chronic wounds), and open (other).

Comparison of encounter subcategories by primary encounter category for those datasets with the primary encounter porportion greater than the primary encounter category proportion of the garrison 2016-2018 dataset.

Comparison of veterinary patient encounters by primary encounter type and dataset.

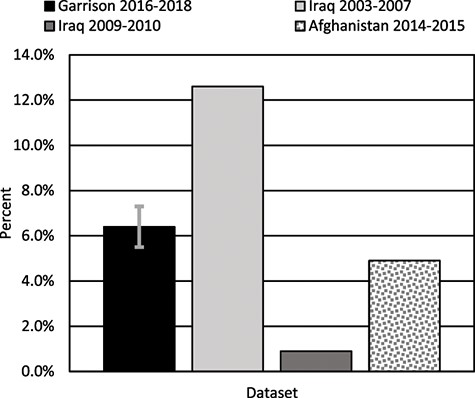

The combat-related encounters in the two Iraq datasets and the Afghanistan 2014-2015 dataset were compared to the emergent encounters in the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset (Fig. 2). When taken as a proportion of non-wellness encounters, the proportion of combat-related encounters were 12.6%, 4.9%, and 0.9% in the Iraq 2003-2007, Afghanistan 2014-2015, and the Iraq 2009-2010 datasets, respectively (Fig. 3). Of the non-wellness encounters in the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset, 6.4% (95% CI: 5.5-7.3) were coded as emergent (Fig. 3).

Comparison of the proportion of garrison 2016-2018 emergent veterinary clinical encounters to combat/battlefield-related veterinary clinical encounters.

DISCUSSION

GOAs, MWDs, and POAs present to the VTF for a wide variety of illnesses. Overall, the top 10 Garrison 2016-2018 encounter categories (90.3%) align with 84.2%, 92.4%, and 85.9% of the encounter categories seen in the Iraq 2003-2007, Iraq 2009-2010, and Afghanistan 2014-2015 datasets, respectively. Although these data imply relatively good coverage of cases seen in the combat environment, a closer comparison of these data identifies potential gaps in readiness training when relying only on the VTF. These gaps could be addressed with appropriate scheduling of clinical patients and through other training modalities.

There were more dental and surgical cases seen in Afghanistan from 2014-2015. This is because of significantly more dental prophylaxes and gastropexies performed on contract working dogs. Generally, MWDs receive a prophylactic gastropexy before shipment to their assigned duty location and a dental prophylaxis before deployment. In contrast, contract working dogs not owned by the military serving in Afghanistan were not required to undergo either procedure before their deployment. Should future deployments include care of contract working dogs, Army veterinarians must be prepared to perform both prophylactic gastropexies and dental prophylaxes.

When compared to the Garrison 2016-2018 dataset emergent cases, the Iraq 2003-2007 dataset had significantly more combat-related injuries. Most of these cases include footpad or paw injuries, laceration not of the footpad or paw, and other. There were a total of five gunshot wounds resulting in death, one case of shrapnel in the abdomen, and eleven improvised explosion blast wave exposures. The data from the Iraq 2003-2007 dataset were abstracted from MWD paper records by the Army veterinarian responsible for care of the MWD at the home station. There were no explicit instructions on how to distinguish a battlefield-related clinical event from a mission-related clinical event, e.g., shrapnel injury from explosion versus a footpad laceration from concertina wire while on patrol.12 This may have led to an overestimation of true battlefield or combat-related injuries in these data. Although there are emergent cases that present to the garrison VTF, the number and type may not be adequate to train Army veterinarians to treat these conditions in the combat and/or forward deployed environment. Considerations to fill these gaps in training should be made and could include surgical surges (co-located Army veterinarians and animal care specialists conducting multiple surgeries over a specified time period outside the normal garrison VTF operation hours), simulated emergency case walk-throughs, joint co-located MDVSS and garrison VTF clinical field exercises, journal clubs, dedicated time to shadow at local emergency clinics, and/or “moonlighting” at local emergency clinics.

LIMITATIONS

There are limitations in these data presented. The combat datasets show a small snapshot of clinical veterinary encounters over a short period of time and may not be representative of all encounters seen during conflict, especially trauma. Although studies have looked specifically at battlefield trauma or injury, there are no overall encounter denominators in these data to be able to compare directly.5 The formation of the Joint Trauma Registry for MWDs, which allows for tracking of clinical veterinary encounters in the combat environment will result in a more accurate reflection of combat data in the future.13 In addition, these data compare past armed conflicts and do not take into account what the future Army multi-domain operations may look like for MWD care and readiness of Army veterinarians and animal care specialists. Although much can be gained from lessons learned, additional studies should model veterinary patient encounters expected on the future operational battle ground.14 The Army veterinarian is only one part of the clinical team in the deployed and garrison environment. Animal care specialists and MWD Handlers also play an important role in MWD health and continuity of care. Ensuring the readiness of these critical team members is also vital, although not specifically addressed at present.

Another identified limitation is the ROVR does not allow for easy export of veterinary patient encounter data, which makes the very simple analysis presented here extremely time-consuming and laborious. In addition, the epidemiologists rely on the ROVR to acquire data needed to calculate clinical readiness metrics monthly. To meet the demands of modernization, the ROVR system must be improved to allow for easy coding of patient encounters so the readiness targets can provide a more meaningful measurement of Army readiness. Once the ROVR and Joint Trauma Registry for MWDs have the capability to measure-specific encounter types, the clinical readiness targets should be updated to more specifically reflect the cases expected to be encountered in the combat environment.

CONCLUSIONS

Ultimately, the success of the DOD Veterinary Services Animal Health mission depends on both the competence and confidence of the individual Army veterinarian. Clinical expertise and confidence can be gained through hands-on case throughput and repetitions, while the foundation for clinical competence involves multi-modal training opportunities to include, but not limited to, case studies, journal clubs, onsite and virtual continuing veterinary medical education, and experience in high-volume veterinary specialty and emergency centers. As the MHS transitions and DOD Veterinary Services continues to transform emphasizing readiness through a public health and prevention-based Army medicine approach, Army veterinarians must strike a delicate balance to continue to provide comprehensive health care to GOAs and POAs in the VTFs. This is especially true considering competing mission priorities and ever-increasing administrative burdens resulting in a risk to and the sacrifice of clinical competencies, medical and surgical skills.

The garrison VTF is the current readiness platform for Army veterinarians and animal care specialists, yet there are opportunities for improvement. Leaders at all levels must recognize the roles VTFs play in overall public health readiness and disease prevention through the proper appropriation and allocation of resources while fostering the development, confidence, and competence of Army veterinarians training within these readiness platforms. The VTF has the potential to serve as a readiness platform if the Army veterinarian can get into the clinic to see patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

APPENDIX: GLOSSARY

Deployment Category medical deployability guidelines that reflect the medical readiness of an MWD. Medical deployment categories are updated by Army veterinarians monthly, at every routine exam or sick call or any time a medical condition develops that warrants a change in the deployment category.15

Deployment Category I (CAT I). Unrestricted Deployment

Medically fit for any contingency or exercise.

Can handle extreme stresses and environments.

No limiting or compromising factors (lack of stamina, etc.).

No existing or recurring medical problems that limit performance or will worsen by stress or increased demands.15

Deployment Category II (CAT II). Restricted Deployment

Medically fit for regions/missions after consideration of known medical problems and consultation with the kennel master (KM).

No significant limiting or compromising factors.

Medical problems may exist which slightly limit performance but are controlled.

Reason for restriction must be reported in the Veterinary Health Record (VHR) and to the KM, MWD unit commander and program managers.15

Deployment Category III (CAT III). Temporarily Nondeployable

Medical condition exists that precludes daily duty performance and is under diagnosis, observation, or treatment. MWD may still be allowed to work at home station, but in a limited capacity.

Reason for non-deployability must be reported in the VHR and to the KM/MWD unit commander.

Estimated Release Date (ERD) from CAT 3 must be reported in the VHR. ERDs will be no longer than 90 days from change to CAT 3 status.

An MWD in CAT 3 requires periodic follow-up exams, further consultation with clinical specialists and consistent reevaluation of the diagnostic and therapeutic plan for return to duty.15

Deployment Category IV (CAT IV). Nondeployable

Unresolved medical or physical problems exist that frequently or regularly impede daily duty performance and ERD cannot be given.

Medical or physical conditions warrant submission to the MWD Disposition Process with subsequent replacement. CAT 4 MWDs are authorized to perform limited missions within their medical condition and training proficiency capabilities at the discretion of the KM and MWD unit commander.

The reason for non-deployability must be reported in the VHR.15

Government-owned animal Government-owned animals include animals owned by the DoD and animals owned by other Federal agencies when existing agreements exist for the provision of care to these animals by the Army.16

Military Working Dog (MWD) This is a generic title for dogs working for the U.S. military. These dogs are differentiated by their job or duty, such as patrol/sentry, explosive, narcotic detection, or a combination, and whether they work independently or with a handler. All branches of the service have MWDs.5

Privately owned animal Privately owned animals include companion animals owned by DoD beneficiaries (active duty service members, retired service members, and reserve service members on active orders).

REFERENCES

Author notes

Preliminary findings were presented to Senior Army Veterinary Corps (VC) leadership at the U.S. Army Public Health Center (APHC) VC Senior Leader Symposium Edgewood, Maryland, March 2018 and the APHC Army Public Health Course, Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, New Jersey, August 2018.

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Military Academy, U.S. Army Public Health Center, U.S. Army, DoD, or the U.S. Government.