-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Emily M Johnson, Ellen Poleshuck, Kyle Possemato, Brittany Hampton, Jennifer S Funderburk, Harminder Grewal, Catherine Cerulli, Marsha Wittink, Practical and Emotional Peer Support Tailored for Life’s Challenges: Personalized Support for Progress Randomized Clinical Pilot Trial in a Veterans Health Administration Women’s Clinic, Military Medicine, Volume 188, Issue 7-8, July/August 2023, Pages 1600–1608, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usac164

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Women Veterans experience a broad range of stressors (e.g., family, relationship, and financial) and high rates of mental health and physical health conditions, all of which contribute to high levels of stress. Personalized Support for Progress (PSP), an evidence-based intervention, is well suited to support women Veterans with high stress as it involves a card-sort task to prioritize concerns as well as pragmatic and emotional support to develop and implement a personalized plan addressing those concerns. Our aims were to explore the population and context for delivery and evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and utility of PSP delivered by a peer specialist to complement existing services in a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Women’s Wellness Center.

This randomized controlled pilot trial compared treatment as usual plus PSP to treatment as usual and used the a priori Go/No-Go criteria to establish success for each outcome. We interviewed staff regarding the population and delivery context at a VHA Women’s Wellness Center and analyzed interviews using a rapid qualitative approach. For the rapid qualitative analysis, we created templated summaries of each interview to identify key concepts within each a priori theme, reviewed each theme’s content across all interviews, and finally reviewed key concepts across themes. We evaluated feasibility using recruitment and retention rates; acceptability via Veteran satisfaction, working relationship with the peer, and staff satisfaction; and utility based on the proportion of Veterans who experienced a large change in outcomes (e.g., stress, mental health symptoms, and quality of life). The Syracuse VA Human Subjects Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Staff interviews highlight that women Veterans have numerous unmet social needs and concerns common among women which increase the complexity of their care; call for a supportive, consistent, trusting relationship with someone on their health care team; and require many resources (e.g., staff such as social workers, services such as legal support, and physical items such as diapers) to support their needs (some of which are available within VHA but may need support for staffing or access, and some of which are unavailable). Feasibility outcomes suggest a need to modify PSP and research methods to enhance intervention and assessment retention before the larger trial; the recruitment rate was acceptable by the end of the trial. Veteran acceptability of PSP was high. Veteran outcomes demonstrate promise for utility to improve stress, mental health symptoms, and quality of life for women Veterans.

Given the high acceptability and promising outcomes for utility, changes to the design to enhance the feasibility outcomes which failed to meet the a priori Go/No-Go criteria are warranted. These outcomes support future trials of PSP within VHA Women’s Wellness Centers.

Women Veterans experience high stress.1,2 Specifically, women Veterans have higher perceived stress (i.e., the perception that their lives are unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded) than the general population of U.S. women (Perceived Stress Scale [PSS] scores were 1.2 SDs higher among women Veterans than norms).1,2 Although the relationships between stress, social determinants of health, and physical health are not yet fully understood, team-based care has been advanced as an important approach to address complex health and social needs.3,4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has standards for women’s health care which build on the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) model to address women Veterans’ unique needs.5 The PACT model is an interdisciplinary team-based approach similar to patient-centered medical homes which includes medical social workers,6 embedded behavioral health providers,7 and, most recently, peer support specialists. Peers are Veterans in recovery from a behavioral health concern with specialized training to support other Veterans.8 Peers working in PACT teams are well positioned to provide navigation and social support for broad, non-diagnostic concerns such as stress compared to clinical providers who largely address medical or psychiatric diagnostic concerns and social workers who address identified social needs.

Despite the existence of VHA standards for gender-tailored interdisciplinary care, women Veterans have poor perceptions of VHA health care and report gender-specific barriers to care.9 A study evaluating women Veterans’ rationale for using VHA care identified problems with patient–provider relationships, organizational and logistic barriers, and problems with Veteran benefits as reasons they discontinued VHA care.10 Gender-tailored services, comprehensive care, and positive patient–provider experiences were reasons Veterans retained care.10 Power asymmetries in the patient–provider relationship can make it difficult for patients to address their priorities.11,12 Peers’ identity and experiential knowledge reduce power asymmetries, inform patient navigation, and allow them to facilitate positive supportive relationships with the health care team.13

Personalized Support for Progress (PSP) is a patient-centered lay-delivered intervention co-created with patients.14,15 PSP uses a prioritization tool to help patients identify their priorities, supports personalized planning, and provides emotional and pragmatic support.14,15 Non-Veteran women with depression and unmet social needs in an obstetrics and gynecology practice who received PSP demonstrated high satisfaction and reductions in depression compared to those who received tailored referrals.14 Based on our clinical experiences with women Veterans and the literature about women Veterans’ needs and barriers to care, PSP was translated to VHA. The PSP prioritization tool is well suited for the competing demands16 that contribute to stress. Furthermore, the social and pragmatic support fit well with peers’ role17 and was ideally suited to address women Veterans’ stressors. Thus, we hypothesized PSP delivered by a peer would meet the needs of Veterans in a VHA Women’s Wellness Center with high stress.

OBJECTIVES

Our objective was to conduct a pilot trial of peer-delivered PSP with women Veterans with high perceived stress in a VHA Women’s Wellness Center. The primary aim was to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and utility of PSP with women Veterans by conducting a small-scale trial based on a larger future trial’s potential design.18 An secondary aim focused on feasibility was to understand the delivery context, specifically staff perceptions of (1) the care needs of women Veterans with unmet social needs and the barriers and facilitators to meeting those needs and (2) clinical experiences working with this population.

METHODS

Design

This randomized controlled pilot trial compared treatment as usual (TAU) to TAU plus PSP. This design allowed us to evaluate the feasibility of recruitment, randomization, and other study procedures. The TAU control evaluated whether PSP could be a meaningful addition to current services. This pilot aimed to establish whether larger studies would be indicated.18 We shifted all research and intervention appointments from in-person to fully remote (phone and mail) early in the study because of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) restrictions.19 A video platform was not adopted because of training and technology challenges. The Syracuse VA Institutional Review Board approved all procedures. This trial is NCT03908190 on clinicaltrials.gov.

Participants

Staff participants

We invited all Women’s Wellness Center staff at the research trial site to participate in brief interviews.

Veteran participants

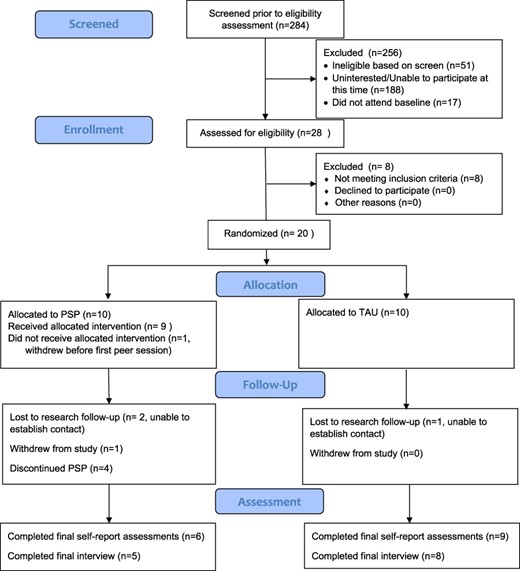

We recruited 20 eligible Veterans from a VHA Women’s Wellness Center through direct marketing, referrals, and electronic medical record reviews (Fig. 1). The sample size of 20 was established a priori to be large enough to offer meaningful results about feasibility, acceptability, and utility (see the Go/No-Go criteria); this sample was not intended to demonstrate efficacy or estimate group effects.20 We collected demographic information to compare conditions on socioeconomic characteristics and evaluate generalizability. Participants self-identified demographic characteristics based on categories defined by the research team. Participants were predominantly non-Latina White women Veterans with an average age of 52.16 years (SD = 11.70) (Table I). Eligible Veterans were clinic patients, approved by their primary care provider for recruitment, reported high stress over the past month (PSS-10 > 18), and could communicate in English. Elevated risk for suicide (i.e., P4 screener21 “higher” risk or “lower” risk plus clinical judgment of risk or instability), homicide, and/or homelessness were exclusion criteria. We also excluded Veterans with current or future psychotherapy appointments, changes to psychotropic medications (past 12 weeks), impairments affecting the ability to use PSP (e.g., active psychosis, cognitive deficits, and inability to attend appointments), and/or current peer services.

| . | TAU group (n = 9a) . | PSP group (n = 10) . | Total sample (n = 19a) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristic . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Age, M (SD) | 52.67 | 12.14 | 51.70 | 11.27 | 52.16 | 11.70 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black/African American | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| Multiple races | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Japanese-American | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| White | 6 | 66.7 | 8 | 80.0 | 14 | 73.7 |

| Ethnicityb | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 8 | 88.9 | 9 | 90.0 | 17 | 89.5 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Education levelc | ||||||

| High school/GED | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Some college | 1 | 12.5 | 3 | 30.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| 2- or 4-year college degree | 6 | 75.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Employment statusd | ||||||

| Employed full-time | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| Employed part-time | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Retired | 2 | 22.2 | 3 | 30.0 | 5 | 26.3 |

| Disabled | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Full- or part-time student | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 10.5 |

| Household incomee | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| $20,000-$39,000 | 3 | 33.3 | 3 | 30.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $40,000-$59,000 | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| $60,000-$79,000 | 4 | 44.4 | 2 | 20.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $80,000-or more | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 22.2 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Married | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Divorced | 4 | 44.4 | 6 | 60.0 | 10 | 52.6 |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Metro/micropolitan area | 6 | 66.7 | 9 | 90.0 | 15 | 79.0 |

| Small town | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Rural area | 2 | 22.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| . | TAU group (n = 9a) . | PSP group (n = 10) . | Total sample (n = 19a) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristic . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Age, M (SD) | 52.67 | 12.14 | 51.70 | 11.27 | 52.16 | 11.70 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black/African American | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| Multiple races | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Japanese-American | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| White | 6 | 66.7 | 8 | 80.0 | 14 | 73.7 |

| Ethnicityb | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 8 | 88.9 | 9 | 90.0 | 17 | 89.5 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Education levelc | ||||||

| High school/GED | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Some college | 1 | 12.5 | 3 | 30.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| 2- or 4-year college degree | 6 | 75.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Employment statusd | ||||||

| Employed full-time | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| Employed part-time | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Retired | 2 | 22.2 | 3 | 30.0 | 5 | 26.3 |

| Disabled | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Full- or part-time student | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 10.5 |

| Household incomee | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| $20,000-$39,000 | 3 | 33.3 | 3 | 30.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $40,000-$59,000 | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| $60,000-$79,000 | 4 | 44.4 | 2 | 20.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $80,000-or more | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 22.2 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Married | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Divorced | 4 | 44.4 | 6 | 60.0 | 10 | 52.6 |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Metro/micropolitan area | 6 | 66.7 | 9 | 90.0 | 15 | 79.0 |

| Small town | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Rural area | 2 | 22.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

One participant was lost to follow-up for baseline self-report measures, which included demographics.

One participant did not report the ethnicity.

One participant did not report the education level.

Participants were able to select all that apply.

One participant did not report the income level.

| . | TAU group (n = 9a) . | PSP group (n = 10) . | Total sample (n = 19a) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristic . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Age, M (SD) | 52.67 | 12.14 | 51.70 | 11.27 | 52.16 | 11.70 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black/African American | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| Multiple races | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Japanese-American | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| White | 6 | 66.7 | 8 | 80.0 | 14 | 73.7 |

| Ethnicityb | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 8 | 88.9 | 9 | 90.0 | 17 | 89.5 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Education levelc | ||||||

| High school/GED | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Some college | 1 | 12.5 | 3 | 30.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| 2- or 4-year college degree | 6 | 75.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Employment statusd | ||||||

| Employed full-time | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| Employed part-time | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Retired | 2 | 22.2 | 3 | 30.0 | 5 | 26.3 |

| Disabled | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Full- or part-time student | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 10.5 |

| Household incomee | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| $20,000-$39,000 | 3 | 33.3 | 3 | 30.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $40,000-$59,000 | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| $60,000-$79,000 | 4 | 44.4 | 2 | 20.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $80,000-or more | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 22.2 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Married | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Divorced | 4 | 44.4 | 6 | 60.0 | 10 | 52.6 |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Metro/micropolitan area | 6 | 66.7 | 9 | 90.0 | 15 | 79.0 |

| Small town | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Rural area | 2 | 22.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| . | TAU group (n = 9a) . | PSP group (n = 10) . | Total sample (n = 19a) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristic . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . |

| Age, M (SD) | 52.67 | 12.14 | 51.70 | 11.27 | 52.16 | 11.70 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black/African American | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| Multiple races | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Japanese-American | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| White | 6 | 66.7 | 8 | 80.0 | 14 | 73.7 |

| Ethnicityb | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 8 | 88.9 | 9 | 90.0 | 17 | 89.5 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Education levelc | ||||||

| High school/GED | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Some college | 1 | 12.5 | 3 | 30.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| 2- or 4-year college degree | 6 | 75.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Employment statusd | ||||||

| Employed full-time | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 21.1 |

| Employed part-time | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Retired | 2 | 22.2 | 3 | 30.0 | 5 | 26.3 |

| Disabled | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Full- or part-time student | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 10.5 |

| Household incomee | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| $20,000-$39,000 | 3 | 33.3 | 3 | 30.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $40,000-$59,000 | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

| $60,000-$79,000 | 4 | 44.4 | 2 | 20.0 | 6 | 31.6 |

| $80,000-or more | 2 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 22.2 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Married | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Divorced | 4 | 44.4 | 6 | 60.0 | 10 | 52.6 |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Metro/micropolitan area | 6 | 66.7 | 9 | 90.0 | 15 | 79.0 |

| Small town | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Rural area | 2 | 22.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 3 | 15.8 |

One participant was lost to follow-up for baseline self-report measures, which included demographics.

One participant did not report the ethnicity.

One participant did not report the education level.

Participants were able to select all that apply.

One participant did not report the income level.

Intervention

Personalized support for progress

PSP involved a prioritization tool asking participants to sort cards reflecting biopsychosocial concerns (e.g., “Getting Basic Things I Need” and “Assistance with Legal Needs”) into piles reflecting “Biggest CHALLENGE for Me,” “Less of a CHALLENGE for me,” and “Not a CHALLENGE for Me.” The peer then helped Veterans complete a structured personalized plan and provided flexible follow-up for practical and emotional support. We adapted PSP to accommodate changes in patient population and provider type. Adaptations included: shifting the language from depression to stress, streamlining and adapting handouts to improve acceptability and accessibility, refining language for a Veteran population (e.g., “challenge” rather than “problem”), and specifying how PSP fits within the VHA and peers’ role. Adaptations were made at two points, before the trial and midway through; half the participants in the PSP group (n = 5) got the first version and half the participants (n = 5) got the second version.

Provider

The peer was an employee who identified as a woman Veteran in recovery from a mental health or substance use concern. In addition to peer certification and training, the peer completed PSP didactic training and obtained regular supervision on PSP delivery including audio review of sessions17 which allowed corroboration that PSP was delivered with fidelity despite the shift to telephone care.

Treatment as usual

The Syracuse VA Women’s Wellness Center includes a range of services (e.g., primary care, gynecology, mental health, pharmacy, social work, wellness coaching, urogynecology, and nutrition) that women Veterans could access as part of TAU.

Measures

Context of delivery: staff acceptability, perceptions of care needs, and clinical experiences

We evaluated delivery context and staff acceptability via semi-structured qualitative interviews (30-45 minutes) which covered (1) care needs of women Veterans with unmet social needs, and barriers and facilitators to meeting care needs; (2) staff experiences with women Veterans with unmet social needs; and (3) provider feedback about PSP.

Feasibility

“Recruitment rate” was the number of eligible participants enrolled by date. “Assessment retention” was the number of participants who completed at least one of the final assessments. “Intervention feasibility” focused on retention, the number of participants randomized to PSP who completed two or more sessions including completion of the card-sort task, development of a personalized care plan, and at least one follow-up visit.

Veteran acceptability with PSP

We assessed “satisfaction with services” using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire, an 8-item self-report with good reliability,22 with Veterans in the PSP arm. Adequate satisfaction was defined as scores in the top half of the scale range.

We assessed patient “relationships with the peer” using the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-SR), a 12-item self-report assessment, with Veterans in the PSP arm. The WAI-SR contains three subscales (goal, task, and bond) with good construct validity and consistent factor structure.23 The words “therapy” and “therapist” were replaced with “peer” and “peer services.” Adequate relationships were defined as scores in the top half of the scale range.

We assessed the “relevance and appropriateness of the card-sort topics” at the post-assessment among all trial participants using a self-report form picturing each card with the questions: “Do your own individual problems or concerns fit within these categories? Yes/No,” “If not, what additional categories would be helpful?” and “Do you have other feedback about these categories?”

Utility

We assessed “stress” with the PSS-10, a 10-item 5-point Likert-type scale with norms from three samples and good construct validity with two subscales: perceived helplessness and perceived self-efficacy.2,24

We assessed “mental health symptoms” with the Brief Symptom Inventory, an 18-item 6-point Likert-type self-report inventory.25 The Brief Symptom Inventory has a global severity index and three dimension scores (somatization, depression, and anxiety).25 It demonstrates good convergent validity with other broad symptom-based measures.25

We assessed the “quality of life” with the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale, a 26-item 5-point Likert-type self-report scale with good validity and reliability for scores related to four domains (physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environment) as well as the overall quality of life.26

We measured “patient engagement with the health care team” with the Brief Health Care Climate Questionnaire, a 6-item self-report single-factor scale with good construct validity and test–retest reliability measuring the quality of the health care team relationship.27,28

We measured “goal attainment” with goal attainment scaling, a technique for evaluating individualized goals involving a two-part semi-structured interview procedure ([1] establish patient goals and baseline functioning with individualized anchors ranging from the worst possible [−2] outcome to the best possible [+2] outcome and [2] evaluate progress at a later date) scored with t-scores.29 Research staff conducted initial interviews at 1 month after intake to allow participants randomized to PSP time to set goals and conducted second interviews at the final assessment (6 months).

Statistical Analyses

A rapid qualitative approach for staff interviews involved generating templated summaries based on a priori themes and matrix analysis of the summaries using an iterative team-based approach to resolve discrepancies and obtain consensus.30 We summarized within and across matrix domains to identify cross-cutting themes.

A Go/No-Go framework31 defined a priori requirements for the feasibility, acceptability, and utility of PSP. If a priori requirements were not met, then those elements would either not proceed to future trials or only proceed with significant modification. Specific criteria for each element are outlined in Table II. We assessed “research feasibility,” “Veteran acceptability” of PSP, and “appropriateness” with descriptive statistics. We also summarized open-ended feedback about the card-sort topics. For the “utility” of PSP, we calculated individual change on outcome measures based on a large effect size (>0.8) and calculated CIs within each group to allow comparison between groups.32

| Outcome . | A priori minimum threshold to progress . | Results . | Go/No-Go . | Response . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention retention (intervention feasibility) | 80% of PSP participants complete >2 sessions, complete the card sort, develop an action plan, and complete ≥1 follow-up visit | 60% (6 of 10) eligible, randomized Veterans | No-Go | For future trials, re-evaluate the referral process to peers, consider streamlining delivery, and consider alternative delivery formats |

| Recruitment rate (research feasibility) | Recruits 20 eligible patients over 4 months (5 per month) | Overall: 3.5 per month Initial: 1.8 per month Final: 9.5 per month | Go | Recruitment was changed to fully virtualb and then the recruitment rate met the threshold |

| Assessment retention (research feasibility) | 80% of all enrolled participants complete each follow-up assessment | 75% completed follow-up | No-Go | In future trials increase follow-up efforts to re-engage participants, streamline assessments, and offer more modalities for assessments |

| Staff acceptability | Staff report high acceptability and feasibility | Staff were unable to provide feedback on PSP | Unable to determine | Unable to be determined because of limited primary care staff interaction with the peer |

| Veteran Acceptability | Participants report high acceptability and satisfaction on measures | CSQ-8: high satisfaction; WAI: strong relationship; card-sort acceptability: 12 of 13 good fit | Go | No response needed; Veteran acceptability was high |

| Change in Veteran outcomes (utility) | More PSP (vs. TAU) participants demonstrate improvements consistent with a large effecta | PSP > TAU for proportion with large individual changes on outcomes (see Fig. 2) | Go | No response needed; outcomes were encouraging |

| Outcome . | A priori minimum threshold to progress . | Results . | Go/No-Go . | Response . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention retention (intervention feasibility) | 80% of PSP participants complete >2 sessions, complete the card sort, develop an action plan, and complete ≥1 follow-up visit | 60% (6 of 10) eligible, randomized Veterans | No-Go | For future trials, re-evaluate the referral process to peers, consider streamlining delivery, and consider alternative delivery formats |

| Recruitment rate (research feasibility) | Recruits 20 eligible patients over 4 months (5 per month) | Overall: 3.5 per month Initial: 1.8 per month Final: 9.5 per month | Go | Recruitment was changed to fully virtualb and then the recruitment rate met the threshold |

| Assessment retention (research feasibility) | 80% of all enrolled participants complete each follow-up assessment | 75% completed follow-up | No-Go | In future trials increase follow-up efforts to re-engage participants, streamline assessments, and offer more modalities for assessments |

| Staff acceptability | Staff report high acceptability and feasibility | Staff were unable to provide feedback on PSP | Unable to determine | Unable to be determined because of limited primary care staff interaction with the peer |

| Veteran Acceptability | Participants report high acceptability and satisfaction on measures | CSQ-8: high satisfaction; WAI: strong relationship; card-sort acceptability: 12 of 13 good fit | Go | No response needed; Veteran acceptability was high |

| Change in Veteran outcomes (utility) | More PSP (vs. TAU) participants demonstrate improvements consistent with a large effecta | PSP > TAU for proportion with large individual changes on outcomes (see Fig. 2) | Go | No response needed; outcomes were encouraging |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease; CSQ-8, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; PSP, Personalized Support for Progress; TAU, treatment as usual; WAI, Working Alliance Inventory.

The original analytic plan was adjusted because the data structure (higher than expected drop-out differentially affecting the PSP group and higher than expected variability affecting normality assumptions) made group analyses for effect size inappropriate. The updated criterion was updated by team consensus after data collection before analysis.

Changes to recruitment methods were already in progress because of problems with the recruitment rate when the trial was temporarily shut down because of restrictions on in-person appointments because of COVID-19 restrictions.

| Outcome . | A priori minimum threshold to progress . | Results . | Go/No-Go . | Response . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention retention (intervention feasibility) | 80% of PSP participants complete >2 sessions, complete the card sort, develop an action plan, and complete ≥1 follow-up visit | 60% (6 of 10) eligible, randomized Veterans | No-Go | For future trials, re-evaluate the referral process to peers, consider streamlining delivery, and consider alternative delivery formats |

| Recruitment rate (research feasibility) | Recruits 20 eligible patients over 4 months (5 per month) | Overall: 3.5 per month Initial: 1.8 per month Final: 9.5 per month | Go | Recruitment was changed to fully virtualb and then the recruitment rate met the threshold |

| Assessment retention (research feasibility) | 80% of all enrolled participants complete each follow-up assessment | 75% completed follow-up | No-Go | In future trials increase follow-up efforts to re-engage participants, streamline assessments, and offer more modalities for assessments |

| Staff acceptability | Staff report high acceptability and feasibility | Staff were unable to provide feedback on PSP | Unable to determine | Unable to be determined because of limited primary care staff interaction with the peer |

| Veteran Acceptability | Participants report high acceptability and satisfaction on measures | CSQ-8: high satisfaction; WAI: strong relationship; card-sort acceptability: 12 of 13 good fit | Go | No response needed; Veteran acceptability was high |

| Change in Veteran outcomes (utility) | More PSP (vs. TAU) participants demonstrate improvements consistent with a large effecta | PSP > TAU for proportion with large individual changes on outcomes (see Fig. 2) | Go | No response needed; outcomes were encouraging |

| Outcome . | A priori minimum threshold to progress . | Results . | Go/No-Go . | Response . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention retention (intervention feasibility) | 80% of PSP participants complete >2 sessions, complete the card sort, develop an action plan, and complete ≥1 follow-up visit | 60% (6 of 10) eligible, randomized Veterans | No-Go | For future trials, re-evaluate the referral process to peers, consider streamlining delivery, and consider alternative delivery formats |

| Recruitment rate (research feasibility) | Recruits 20 eligible patients over 4 months (5 per month) | Overall: 3.5 per month Initial: 1.8 per month Final: 9.5 per month | Go | Recruitment was changed to fully virtualb and then the recruitment rate met the threshold |

| Assessment retention (research feasibility) | 80% of all enrolled participants complete each follow-up assessment | 75% completed follow-up | No-Go | In future trials increase follow-up efforts to re-engage participants, streamline assessments, and offer more modalities for assessments |

| Staff acceptability | Staff report high acceptability and feasibility | Staff were unable to provide feedback on PSP | Unable to determine | Unable to be determined because of limited primary care staff interaction with the peer |

| Veteran Acceptability | Participants report high acceptability and satisfaction on measures | CSQ-8: high satisfaction; WAI: strong relationship; card-sort acceptability: 12 of 13 good fit | Go | No response needed; Veteran acceptability was high |

| Change in Veteran outcomes (utility) | More PSP (vs. TAU) participants demonstrate improvements consistent with a large effecta | PSP > TAU for proportion with large individual changes on outcomes (see Fig. 2) | Go | No response needed; outcomes were encouraging |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease; CSQ-8, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; PSP, Personalized Support for Progress; TAU, treatment as usual; WAI, Working Alliance Inventory.

The original analytic plan was adjusted because the data structure (higher than expected drop-out differentially affecting the PSP group and higher than expected variability affecting normality assumptions) made group analyses for effect size inappropriate. The updated criterion was updated by team consensus after data collection before analysis.

Changes to recruitment methods were already in progress because of problems with the recruitment rate when the trial was temporarily shut down because of restrictions on in-person appointments because of COVID-19 restrictions.

RESULTS

Four staff members participated in interviews. Of the 20 eligible Veteran participants, 15 completed follow-up assessments (Fig. 1).

Clinical Context: Staff Acceptability, Perceptions of Care Needs, and Clinical Experiences

Staff members described three important considerations (cross-cutting themes) for addressing the needs of women Veterans. First, women Veterans experience multiple social, emotional, and physical concerns unique among women which increase the complexity of care. For example, food insecurity, relationship concerns, housing, childcare, employment, and transportation impact access to care. Staff explained that women Veterans also experience unique barriers to using existing services. For instance, women Veterans with unmet childcare needs, time demands, and/or discomfort being in close quarters with men have difficulty using appointment transportation services.

The second cross-cutting theme was that women Veterans need: (1) safe, trusting, consistently responsive providers for support and (2) assistance with accessing practical resources. Staff thought that VHA makes good efforts and provides many services to meet the social needs of women, but that this was difficult because of limited resources (e.g., staffing and time). Furthermore, women Veterans’ stress can impact their sense of urgency and frustration. The staff described being “spread thin” so that they are sometimes unable to respond in the moment. Moreover, staff described that lacking sufficient time made it challenging to develop trusting relationships. Respondents wanted to see VHA provide more staff for existing positions (e.g., social worker, care manager, and peer specialist) and more resources (e.g., clothing, deodorant, school supplies, and diapers) for social needs. Staff thought offering services within the VHA vs. connecting Veterans with community resources was important.

Finally, staff expressed a desire for additional resources not currently provided or adequately covered (e.g., legal services, support for women with special needs children, and support groups), women-focused programs (e.g., female peer specialists and separate spaces), training and support for staff (e.g., awareness of VHA services and communication skills), more access to comprehensive care management, and more time allocated for the care of women Veterans.

Staff members were unable to provide direct feedback on PSP citing a lack of opportunity to work directly with the peer. (Lack of opportunity to work with the peer was likely attributable to a combination of [1] the peer’s part-time schedule and [2] all staff members, including the peer, transitioned to telework midway through recruitment because of COVID-19 safety protocols.)

Feasibility

Initial recruitment requiring in-person consent and baseline assessment resulted in a recruitment rate below the pre-specified 5 per month (Table II). Following the transition to telephone procedures, the recruitment rate increased well above the necessary threshold. The assessment retention rate was also below the pre-specified retention rate of 80%. The intervention retention rate was 60%, below the pre-specified rate of 80%. Three Veterans initiated with the peer but did not complete sufficient elements of PSP, one of whom withdrew before her first session. We were unable to re-establish contact with Veterans who did not complete PSP to further evaluate reasons for drop-out.

Veteran Acceptability

Participants (n = 6 final PSP arm respondents) reported high satisfaction with PSP (Client Satisfaction Questionnaire M[SD] = 3.71[0.64] on a 1 [low satisfaction] to 4 [high satisfaction] scale, range = 3.38-4). No items had ratings below the midpoint (range: 3.33-4.00). Participants (n = 6) reported strong relationships with their peers. All WAI subscale scores fell in the range of the highest two response options (4-5 on a 1-5 scale). Goal scale scores were between 4.25 and 5, M(SD) = 4.54(0.29); task scale scores were between 4 and 5, M(SD) = 4.5(0.35); and bond scale scores were between 4 and 5, M(SD) = 4.79(0.40).

All participants had the opportunity to provide feedback on the card-sort topics; 12 (of 13, 92.9%) reported their concerns fit within available categories.

Utility

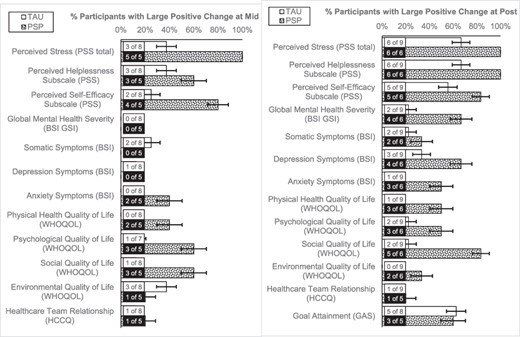

At the mid-assessment, a larger proportion of individuals in the PSP arm had a large positive change compared to the TAU arm for perceived stress (including self-efficacy and hopelessness), anxiety, and physical health, psychological, and social quality of life as demonstrated by non-overlapping CIs (Fig. 2). At the final time point, a larger proportion of individuals in the PSP arm had a large change compared to the TAU arm for perceived stress (including self-efficacy and hopelessness), global symptom severity, depression, anxiety, and quality of life (physical health, psychological, social, and environmental) as demonstrated by non-overlapping CIs.

Patient outcomes related to the efficacy of PSP at the mid-assessment and the final assessment.

DISCUSSION

This randomized clinical pilot trial comparing TAU to TAU plus PSP in women Veterans with high stress demonstrated encouraging results for Veteran acceptability and utility. Adjustments to enhance feasibility are necessary before future trials. Staff perceptions suggest that interventions like PSP which are tailored for women Veterans with complex presenting concerns, incorporate designated staff to respond to needs for emotional and practical support, and facilitate access to resources will meet the needs of this population. Staff thought that VA provides many resources (e.g., social work and behavioral health) and more are available through community partnerships (e.g., legal services), but better access and additional support in identifying and navigating resources would benefit both Veterans and staff. The results suggest that PSP is likely to be well received by women Veterans. The results for patient outcomes are encouraging and suggest appropriateness for advancing to full clinical trials.

Research feasibility did not meet the Go/No-Go criteria, highlighting a need to modify the design for future trials. The recruitment rate increase following the implementation of telephone procedures suggests that future trials with this population should consider fully remote/virtual participation options, including video to increase feasibility.19 Ultimately, having a wide range of platforms may achieve the best reach by allowing accommodation of Veteran and peer preferences, technical abilities, technology access, and mobility.19 Assessment retention also did not meet pre-specified criteria and warrants design changes. Future trials should consider reducing assessment burden, increasing staff follow-up, specifying a time frame rather than a time point for completion (e.g., 6-8-month vs. 6-month follow-up), and allowing multiple options for completion (e.g., telephone, online, mail, and in-person).

Despite high acceptability, intervention retention did not meet the Go/No-Go criteria. To reduce potential barriers to initiating PSP, future trials could implement warm handoffs, a strategy used to increase behavioral health initiation in primary care. Warm handoffs are a staple of in-person primary care and involve an introduction to the peer from another staff member during another appointment. Increased virtual care through the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in recommendations on maximizing team-based care, including warm handoffs, virtually.33

Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths include targeting an underserved population within the VA, utilizing a peer-delivered and person-centered approach, and use of a comparison group despite the small sample. The pandemic changed our methods unexpectedly, but the pivot to a telephone format was associated with improved recruitment. The small sample in a single location with one peer limits generalizability. Limited assessment retention may also mean that the results fail to reflect the overall study sample’s experiences. PSP was not well integrated into clinical care; thus, staff did not feel confident commenting on it, and we were unable to assess provider acceptability.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings are encouraging that peer-delivered PSP in a VA Women’s Wellness Center is acceptable to women Veterans and has promising utility to address their needs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Melinda Bullock, Certified Peer Specialist, for her contributions to the manual and service to the Veterans who received Personalized Support for Progress as a part of this study.

FUNDING

This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Center for Integrated Healthcare Pilot Research Grant awarded to Dr. Johnson and Dr. Poleshuck (co-Principal Investigators).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Author affiliations reflect affiliations at the time the work was done, and Brittany Hampton has since taken a position at the University of Mississippi.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.