-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Melissa Weihmayer, Multilevel governance ‘from above’: Analysing Colombia’s system of co-responsibility for responding to internal displacement, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 37, Issue 2, June 2024, Pages 392–415, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fead071

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

States bear the responsibility for the protection of people displaced internally by conflict and other causes. Though widely recognized, there is little research on how the state shares that responsibility between different levels of government. Colombia serves as a useful case for examining the evolving coordination between national and local governments. I conduct a thematic analysis of its 2015 Strategy of Co-responsibility regulating emergency humanitarian assistance. I argue that the Strategy represents a delicate compromise between enforcing minimum standards and respecting local autonomy. This means the System largely reaffirms existing vertical power relations, while also creating incentives for horizontal multilevel governance. The article explores the Strategy’s use of the language of ‘co-responsibility’, a technocratic action-planning process, and capacity-building initiatives. I propose frameworks from the literature on the multilevel governance of migration to identify the conditions for coordination between levels to emerge, bridging multilevel governance literature with forced migration literature.

Introduction

In the municipality of Ituango in late July 2021, threats of violence and forced recruitment by non-state armed actors forced over 4,000 residents to leave their homes in the span of a week (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs 2021). Early alert systems triggered a state response to this mass displacement within a few days. A Local Committee for Transitional Justice was convened to coordinate the humanitarian response, featuring the mayor of Ituango, the police force, the ombudsman, and the ‘Victim’s Unit’,1

The government agency leading the national response is the Unit for the Attention and Comprehensive Reparation to Victims (Unidad para la atención y reparación integral a las víctimas), henceforth referred to as the ‘Victim’s Unit’.

Over twelve years earlier, solutions for coordinating responses to internal displacement at the local level seemed untenable. At a workshop convened by Acción Social (precursor to the Victim’s Unit) and other partners,2

This included the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the Representative of the Secretary-General on the Human Rights of IDPs, and academic partners.

With the compounding challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, substantial numbers of Venezuelans seeking refuge in Colombia, and continued violence such as in the case of Ituango, coordination between various levels of government to respond to these complex problems is as important as ever. The response to internal displacement is now transitioning from a peacebuilding initiative into a long-term welfare program, given that its cornerstone 2011 Victim's and Land Restitution Law (Ley de Víctimas y Restitución de Tierras, Law 1448, Colombia: Congress of the Republic 2011a; hereinafter referred to as ‘Victim’s Law’) has now been extended to 2031. This makes it an important moment to analyse Colombia’s national–local coordination as a case of multilevel governance.

In this article, I seek to understand how the national level attempts to resolve tensions between levels. I also explore how literature on the multilevel governance of migration helps to explain the conditions needed for more coordinated responses to emerge in situations of internal displacement. Concretely, this article examines Colombia’s official state policies coordinating the national, regional, and local levels. It focuses on the ‘System of Co-responsibility’, the approach for administering emergency humanitarian assistance to Colombians displaced by decades of armed conflict. While other aspects of the internal displacement response are managed by national government agencies operating locally, this is the main expectation placed on municipal governments. I ask three questions: (1) How does the System of Co-responsibility reflect and further shape power dynamics between levels? (2) How does it create conditions for multilevel governance (or not), according to frameworks from the multilevel governance of migration? And, (3) what does this reveal about the multilevel dimensions of internal displacement responses more broadly?

To respond to these questions, this article adopts a qualitative approach based on an analysis of the 2015 ‘Strategy of Co-responsibility’ (Colombia: President of the Republic 2015), supported by a thematic analysis of key state documents and secondary literature. The article proceeds as follows: first, it assesses the multilevel dimensions of internal displacement. It then explains the relevance of multilevel governance as an object of study, not just as a description of a complex policy context. Next, it reviews the existing literature on forced migration and multilevel governance to demonstrate the gap for internal displacement responses. The empirical section analyses the discourse and content of the Strategy of Co-responsibility, placing it within its historical, socio-political, and administrative context. It examines the development of the concept of co-responsibility, an action-planning process, and capacity building practices. Finally, it interprets Colombia’s approach to national–local coordination through conceptual frameworks on the multilevel governance of migration.

Consequently, the article contributes to the forced migration literature by providing the first discussion of internal displacement response as a case of multilevel governance. But it also connects dilemmas in forced migration with wider governance issues. I argue overall that the multilevel dimensions of internal displacement require a delicate compromise between enforcing minimum standards for local responses and respecting local autonomy. The System of Co-responsibility does this by largely reaffirming existing power relations, illustrating how internal displacement responses are embedded within broader decentralization debates.

The Multilevel Dimensions of Internal Displacement

This section explains why responding to large-scale internal displacement creates both political and spatial challenges with multilevel dimensions. Nascent literature on the urban dimensions of internal displacement demonstrates a need to overcome the relative ‘invisibility’ of urban internally displaced people for local, national, and international actors alike (Fielden 2008; Lyytinen 2009; Aysa-Lastra 2011; Landau 2014; Cotroneo 2017; Earle et al. 2020). With the majority of people internally displaced seeking refuge in urban or at least in ‘non-camp’ settlements (UN High Commissioner for Refugees 2019), they are likely to encounter the local state in its varied forms, even in the absence of a planned state response.

Bringing internal displacement into multilevel governance discussions overcomes a national bias in the scholarship on internal displacement responses. Sociolegal literature assumes decision-makers reside primarily at the national level, with local-level actors relegated to an ‘implementer’ role (Ferris et al. 2011, p. 75). Though in some cases the dissemination of the laws and policies to local levels has been considered the problem (Ferris et al. 2011; Carr 2009), more common is that local governments are blamed for any failures in implementation, with frequent references to their lack of capacity. Meanwhile, evidence is growing that local government engagement in the design as well as the implementation of responses is critical for adapting to local political dynamics and concerns (Lopera Morales et al. 2009; Earle et al. 2020). This suggests that greater collaboration between levels in this policy area is both feasible and beneficial.

Underpinning the complications of roles and responsibilities are the inherently political dilemmas of internal displacement responses. A response requires balancing tailored programs and services for the displaced with those benefiting entire communities. For local governments, this implies struggles to ensure equity among constituents: ‘… municipal authorities face an ethical problem: assisting the displaced population is done at the cost of assisting vulnerable populations (such as the historical poor)’ (Brookings-Bern Project on Internal Displacement 2008, p. 12). This concern relates to a contentious debate within forced migration research that questions the relevance of the category of ‘internally displaced people’ (Polzer and Hammond 2008; Daley 2013; Brun et al. 2017). The category, developed over time and in response to confusion around the authority of the United Nations to intervene within internal armed conflicts (Phuong 2004; Mooney 2005; Weiss and Korn 2006; Cohen 2007; Orchard 2016), singles out a group of citizens as exceptional. This special category may seem reasonable given that citizens forced to flee situations of conflict or violence likely need specific services and protections not available to the rest of the population. But it also becomes problematic in contexts where their needs become indistinguishable from others living in the same areas, as is often the case in precarious urban peripheries (Landau 2014; Cotroneo 2017). In the districts of Suba and Ciudad Bolivar in Bogotá, for example, most residents live in poverty with daily exposure to urban violence, yet those that qualify officially as internally displaced benefit from certain services that the host community does not (Vidal et al. 2011). This can produce tensions between displaced and host communities.

In addition, different regions experience the impact of displacement differently, making a tailored response critical. For example, Colombia’s Constitutional Court documented cases of municipalities losing half their population while others gained more than 20% in a short amount of time (Vidal et al. 2013, p. 1). Such volatility represents a significant spatial challenge that makes it difficult for national governments to intervene in the place of greatest need. This is underpinned by uneven economic development that leaves some municipalities better equipped for responding than others. Any response to internal displacement must therefore not only acknowledge these differences but develop processes for understanding and adapting to them as the situation changes over time. This necessarily requires that different levels of government and society be actively engaged in the response’s overall governance.

Facing Multilevel Problems with Multilevel Governance

This section reviews the literature on multilevel governance to demonstrate its relevance for forced migration contexts. Though some problems clearly have multilevel dimensions, it is not necessarily the case that their governance will be multilevel. Governance can be understood as processes of binding decision-making in the public sphere (Marks and Hooghe 2004). At its simplest, multilevel governance can be observed as ‘some form of coordinated interaction between various government levels’ (Scholten 2013, p. 220), as well as between government and civil society, that enables joint decision-making (Caponio and Jones-Correa 2018). Marks and Hooghe (2004) distinguished between interactions vertically between different levels of government and those horizontally between government and civil society actors (Bache and Flinders 2004). Indeed, horizontal relations have become increasingly important in the governance of migration in general (Ataç et al. 2020). This is because it is widely believed that the State no longer has the authority to make these decisions on its own (Behnke et al. 2019) and must rely on networks of various kinds of stakeholders for both policymaking and implementation (Rhodes 1997; Bevir 2011; Zurbriggen 2011). How openly the State acknowledges interdependencies between levels of government and with civil society organizations in their policy discourse is an empirical question, which I examine through the System of Co-responsibility in Colombia.

Literature specifically on the multilevel governance of migration has blossomed in the last decade (Scholten 2013, 2016; Caponio and Jones-Correa 2018; Scholten et al. 2018; Panizzon and Van Riemsdijk 2019). This literature underlines the relevance of multilevel governance in migration contexts because migration creates a series of ‘intractable controversies’ in which the problem definition is inherently contested (Schon and Rein 1994 cited in Scholten 2013, p. 219). Hence, much work must be done to achieve a shared framing of the problem both within and outside of government to clarify who is responsible for solving it and how. In addition to the complex problem-framing, many authors have noted that the locus of power has shifted to other scales. Migration policymaking was assumed to be exclusively the responsibility of the national level, but now there is growing recognition of the agency of local levels (Scholten 2013; Zapata-Barrero et al. 2017; Oliver et al. 2020). These now extensive debates, referred to as the ‘local turn’, are countered by compelling arguments that the study of national-level policies and their influence should not be forgotten (Emilsson 2015) and that the local turn is not as promising as it initially seems given restricted local autonomy (Bernt 2019). These shifts demonstrate the relevance of studying the interactions between the local, regional, and national levels rather than overemphasizing one or the other. The concept of multilevel governance enables this.

Illustrating the presence of vertical and horizontal interactions helps to describe relations in a complex policy process, but alone it fails to explain the implications of those relations. These are questions such as whether and how multilevel governance increases problem-solving capacity, the legitimacy of policy decisions, or democratization in general (Stubbs 2005; Bache and Flinders 2004; Piattoni 2010; Griffin 2012; Stephenson 2013). Multilevel governance involves trade-offs, for example between efficiency and legitimacy: involving more actors in a policymaking process could produce wider input and buy-in, but requires additional resources to coordinate (Marquardt 2017). We therefore need to avoid normative claims on the implications of multilevel governance.

This prompts the question of how multilevel governance shapes and is indeed shaped by power relations (Marquardt 2017). Multilevel governance assumes some degree of power-sharing between actors, but the nature and extent of that power-sharing varies and changes over time. Methodologically, this suggests the need to not just describe multilevel governance arrangements but rather “seek to uncover the extent to which [they] challenge or consolidate established power relationships and governing traditions” (Polat and Lowndes 2022, p. 57). Bringing this back to internal displacement responses, this acknowledges that the state and non-state actors developing those response structures are embedded within asymmetric political landscapes. The structure of the response itself has the potential to reaffirm or alter existing power relations. It does this through the way it distributes decision-making power and resources, influencing which individual, entity, or level of government has the capacity to use those resources (Marquardt 2017). Individual relationships between actors also matter, because “power relations are not preset in models, territories or networks: they are made and remade in relationships, exchanges and interactions” (Griffin 2012, p. 209). I later present and adapt a framework from Peter Scholten to propose that consensus-building through regular interactions and the flattening of hierarchies between levels can lead to a cooperative mode of multilevel governance.

Multilevel Governance of Displacement Responses

This section bridges multilevel governance literature with forced migration literature. Though multilevel governance is now well-established in migration policymaking, its traction in refugee studies is sparse by comparison. Refugee reception and integration literature is starting to build on these foundations (Oliver et al. 2020) but mostly in the context of European cities. Outside this context, some studies view multilevel governance as the assumed context within which actors operate without interrogating its dynamics (see for example Betts et al. 2021). This reflects a broader refugee literature that acknowledges the unique urban dimensions of refugee policy and politics, in its own version of the ‘local turn’ (Landau and Amit 2014; Darling 2017; Pasquetti et al. 2019; Lowndes and Polat 2022; Irgil 2022; Maas et al. 2022; Brumat et al. 2022). While important for analysing the gap between policy and implementation at local levels, we need to ask how sharing responsibility for implementation is negotiated in the first place. Two studies focus explicitly on the multilevel governance arrangements of refugee responses (outside Europe) that start to rectify this gap: Fakhoury (2019) in Lebanon and Jordan and Polat and Lowndes (2022) in Turkey, both analysing responses to Syrian displacement.3

Marti (2019) also studies multilevel governance of migration in Singapore but applied to domestic migrant workers rather than forced migrants.

Polat and Lowndes’ research provides a useful counterpoint for the Colombian response. They argue that in the Turkish context, with its highly centralized political system and weak local government, multilevel governance arrangements emerged ad hoc for responding to the arrival of Syrian refugees. This arose out of an absence of central government resources and interventions, driving local NGOs to collaborate directly with international NGOs to fund, design and implement programs. This in turn built some capacity for local government activities as they took on a critical convening role. However, this capacity was not transformative; rather, “existing power relationships and governing traditions of the Turkish polity are largely (although not exclusively) reproduced” (p. 52). For example, there was no evidence that local governments could influence national government refugee issues (Polat and Lowndes 2022, p. 67). With the Colombian case, by contrast, I focus on the national-level policies attempting to establish multilevel governance arrangements and their potential to rebalance power relations. After a brief overview of Colombia’s response to internal displacement, I will outline my methodology.

Colombia’s Response to Internal Displacement: Case Selection

Here I explain the relevance of focusing on internal displacement responses in Colombia. While working as a practitioner in various internal displacement contexts in Central America, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East from 2015 until 2019, Colombia’s state-led response served as the benchmark by which to measure the comprehensiveness of responses elsewhere. Colombia’s response to internal displacement presents ample evidence on the different ways they can be governed in a (decentralizing) unitary system. First, the legislation passed to establish a state-led response is comprehensive because it covers not only humanitarian assistance but also development programs, prevention of new displacement, return of land, and reparations. Second, the sheer duration of the armed conflict and internal displacement that ensued has elicited a wealth of civil society and academic research (Ferris 2014; Sánchez-Mojica 2020) that enables a deep analysis of secondary literature. Third, compared to other contexts with internal displacement, international humanitarian actors have had a comparatively small role. Colombia’s response has been touted as a model to follow, with other internal displacement contexts incorporating its features such as its official government registry (European Commission 2018), making it a clear originator of policy transfer and learning. This has also extended to its work with other displaced groups. An estimated 2.48 million Venezuelans have sought refuge in Colombia since 2014 (Cancillería 2023a),4

Migración Colombia, a special administrative unit within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, cite 2,477,588 Venezuelans residing in Colombia as of 28 February 2022. This includes Venezuelans with: ‘regular status’, temporary protection status, in process for temporary protection status, and ‘irregular status’. As of the date of this article’s publication, this is the latest government-issued figure available for total numbers of Venezuelans that arrived since 2014, though registration for Temporary Protection Status is ongoing.

By the end of 2022, 1.6 million Venezuelans in Colombia had received temporary protection permits (UNHCR 2023, p. 75).

Despite being the ‘model context’, significant gaps remain in the implementation of its response to internal displacement (Ibáñez and Moya 2007; Wong 2008; Ibáñez 2008; Carr 2009; Ferris 2014; Ruiz Romero 2015; Aparicio 2017; Meza and Ciurlo 2019; Cronin-Furman and Krystalli 2021). This is particularly the case for internally displaced people living in urban settings (Carrillo 2009; Vidal et al. 2011; Aysa-Lastra 2011; Sánchez-Mojica 2013; Victim's Unit 2021a). The numbers remain significant, and increasing every year, albeit at lower rates than at the height of the displacement crisis in 2000–02. The official government registry reports 9.54 million victims of the armed conflict, of which the majority are victims of forced displacement (8,498,363 people according to August 2023 figures: Victim's Unit 2023).6

As of 2011, ‘victims’ are defined as the people who individually or collectively suffered harm after 1 January 1985 as a consequence of infractions of international humanitarian law or grave and manifest violations of international human rights norms, which occurred on the occasion of the internal armed conflict (Colombia: Congress of the Republic 2011a: Article 3). This includes forced displacement and forced dispossession of land but also homicide, kidnapping, sexual violence, exposure to explosive remnants of war, and others.

This represents approximately 0.53% of GDP (OECD 2021).

Methodology

To explore Colombia’s national–local coordination policies, I selected twelve documents on the official state response based on their relevance for coordination. This included decrees issued by the national level, national laws, a landmark 2004 Constitutional Court decision (Sentencia T-025/04), and guidelines developed by the Victim’s Unit. It is important to note that there is no mention of multilevel governance within the policy documents; rather the term ‘coordination’ is used to cover a broad range of relationships and negotiations between the local and national levels.

I conducted a thematic analysis of these documents, coding them in NVIVO software. I followed Attride-Stirling’s (2001) process of moving from basic themes close to the text to organizing themes and then onto global themes that “tell us what the texts as a whole are about within the context of a given analysis” (p. 389). Basic themes identified responsibilities assigned to the local level, to the national level, responsibilities shared between levels, and how various ‘principles of governance’ were described. I also identified any descriptions of administrative decision-making processes to determine how responsibilities could be negotiated between levels. I organized these into indications of competition and collaboration between levels. These revealed, as global themes, how key tensions were understood by the national level, and how they envisioned overcoming them.

Of this larger corpus, I conducted a deep reading of the Strategy of Co-responsibility (Colombia: President of the Republic 2015; hereinafter referred to as the ‘Strategy’), a presidential decree issued by the administration of former president Juan Manuel Santos in 2015. This decree represented the culmination of decades of debate on how to manage national–local relations in this policy area. For this reason, the empirical material presented in this article centres around the discourse and content of this Strategy.

Contextualizing information on the shape of the national response was given by an interview with a former Advisor in the Victim’s Unit, and the Victim’s Unit website subsection ‘Nación Territorio’ (Victim's Unit 2021b). Three existing studies on the role of municipalities in Colombia’s internal displacement response were also essential to situate the corpus in its historical and social context (Ibáñez and Velásquez 2008; Lopera Morales et al. 2009; Vidal et al. 2013). This gives some understanding of how the national-level policy narrative compares with the challenges experienced and expressed by municipalities. Additionally, I reviewed local action plans (Plan de Acción Distrital) from the capital city of Bogotá covering 2016–20 and 2020–24 as more recent examples of the response to national-level directives (Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá 2016; 2019).

In my analysis of the Strategy, I was inspired by two other methodological approaches. First, critical discourse analysis’ interest in making the implicit explicit helps ask how assumptions underpinning discourse can be used to legitimize control and naturalize certain power relations (Fairclough 1985 cited in Van Dijk 1993). The discourse-historical approach to critical discourse analysis (Wodak and Reisigl 2016) prompted me to take a close examination of the text. I followed their process of identifying the tensions that lie within the text, connecting these to the ideological positioning of the policy, and asking how these shape power relations through the identities, behaviours, and understandings the text promotes. Second, rather than evaluating whether the policy achieved its stated aims, I was more interested in the question prevalent in the field of political anthropology: “What work did this policy do?” (Tate 2020, p. 87). In this, I treated the Strategy as a ‘policy narrative’ of the national level describing the future it envisions for national–local relations. Such narratives “make political action legible, locating specific programs within broader spheres of political value, as well as erasing and obscuring alternatives” (Tate 2020, p. 86). Hence, these approaches enable me to respond to calls from Polat and Lowndes (2022) and Marquardt (2017)8

Marquardt argued for the importance of conceptualizing power within multi-level climate governance. Because of the similar levels of complexity, variety of stakeholders involved, and multilevel dimensions of internal displacement, I view Marquardt’s arguments for climate action as transferrable to forced migration responses.

The Strategy of Co-Responsibility: A Process towards Multilevel Governance?

This empirical section addresses the question of how the System, through its 2015 Strategy of Co-responsibility, reflects and further shapes existing power dynamics. This Strategy can be usefully read as a policy for multilevel governance ‘from above’, contrasting Scholten et al.’s (2018) study ‘Multilevel governance from below: how Dutch cities respond to intra-EU mobility’. Though from the vantage point of the national level, I argue that the Strategy offers a compromise between a top-down and a bottom-up arrangement.

I identify three tactics the Strategy uses to negotiate responsibility-sharing: the language of ‘co-responsibility’, implementing an action-planning process, and offering joint-funding opportunities alongside capacity-building initiatives. These attempt to respect local autonomy while also incentivizing a tenuous local ownership of the response. It does this by creating space for tailoring local responses while enforcing minimum standards and confronting disparities in governance capacity between municipalities. I argue that this compromise relies on technocratic decision-making processes to depoliticize multilevel tensions.

The Language of Co-Responsibility

The level responsible for funding emergency humanitarian assistance and other local programs for people displaced internally has been a longstanding debate. This must be understood within broader decentralization processes that Colombia has been undergoing since the 1980s. The 2015 Strategy acknowledges and in part regulates how decentralization is managed in this policy area. It does this by discursively separating the concepts of co-responsibility and subsidiarity. First, I explain how the concept of co-responsibility came about.

The language of co-responsibility stems from the groundbreaking constitutional court ruling Sentencia T-025/04 (Corte Constitucional 2004) in 2004 that judged the state response to internal displacement unconstitutional given that the basic rights of those internally displaced were not being filled. The ruling considered the lack of coordination mechanisms and ambiguity of roles and responsibilities in the initial Law 387 as key impediments. In an associated order the court called for the national government to create a “model of co-responsibility with the territorial entities for the attention of the displaced population” (Corte Constitucional 2013, Section 1.2; emphasis added). This model was seen as a key task for the national government to design.

A resurgence of the concept of co-responsibility came in 2010 in the form of a publication entitled Establishing an integrated system of co-responsibility between the Nation and the Territories.9

This publication was developed by the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento, henceforth referred to as ‘CODHES'), a civil society organization with high-profile academics and policy advisors.

guaranteeing the adequate coordination between the Nation and its local entities, and between these, for the exercise of their competencies and functions within the System in accordance with the constitutional and legal principles of co-responsibility, coordination, concurrence, subsidiarity, complementarity and of delegation (Colombia: Congress of the Republic 2011a, Art. 161; emphasis added).

The main principles of decentralization mentioned above are listed in the 1991 Constitution—coordination, concurrence, and subsidiarity (Art. 288). These are meant to guide the distribution of competencies between national, regional, and local levels in the absence of clearer directives. The laws for territorial planning (e.g. Law 1454 of 2011; Ley Orgánica de Ordenamiento Territorial) do not establish a process for distributing functions and competencies to the appropriate level (Duque cante 2012). This means that for the most part, competencies are expected to be outlined on a law-by-law basis. If this is not done clearly, this risks confusion across various functions of subnational government in Colombia, especially between the municipal and departmental levels.

While the other principles relate to all policy areas, the concept of ‘co-responsibility’ is different. It is specific to guaranteeing and protecting human rights. Its legal basis is in Decree 4100 of 2011 (Art. 4), which declares actions to respect and guarantee the protection of human rights and application of international humanitarian law to be the responsibility of all public entities, at national and subnational levels (Cancillería 2023b). The principle of ‘co-responsibility’ creates a normative argument for local levels to ‘do their part’ for people displaced internally and other victims of the conflict. This makes the case that responsibility-sharing for the protection of human rights applies regardless of progress towards decentralization (or lack thereof).

In addition to this normative framing, the Strategy nudges compliance from the local level by limiting how the other principles of decentralization can be applied in this context, especially the application of subsidiarity.10

The other principles of decentralization are less contentious. The principle of coordination requires that the competencies of different levels of government be exercised “in an articulated, coherent and harmonized manner” (Colombia: Congress of the Republic 2011b, Art. 26), while the opportunity for concurrence arises when two or more levels of government combine their specific competencies and resources to implement a certain activity or program.

The System of Co-responsibility thus paints over gaps created by partial decentralization. The structure of its response to internal displacement is not decentralized, instead it is ‘deconcentrated’.11

Interview, former Advisor in the Victim’s Unit.

Though the response overall is managed by the national level, the provision of emergency humanitarian assistance is the exception. It is municipalities, not the Victim’s Unit or other government levels, that are legally responsible for administering emergency humanitarian assistance to victims upon arrival. This includes temporary accommodation, food and clothing for three months, extendable to six. These services are expected to meet victims’ most urgent and basic needs after displacement, and hence are framed as a critical first step on the pathway to restore their rights (Alcaldía de Bogotá 2018). In theory, this gives local governments autonomy over this policy area. In practice, municipalities contested this arrangement because no additional funding was allocated to them to match their increased obligations (Vidal et al. 2013). The National System, established in 1997, required that all levels of government be involved in the response. This did not sufficiently outline activities that should be taken by local authorities (Ibáñez and Velásquez 2008, p. 34) and failed to specify a minimum budget that municipalities should allocate to services for those internally displaced, resulting in their being grouped in with other vulnerable populations (Ibáñez and Velásquez 2008, p. 23). This led to confusion at best, negligence at worst. Local levels were not able to and, in some cases, not willing to implement policies to support victims of the armed conflict.

Because obligations generally did not match their budgetary capacity, Ibáñez and Velásquez (2008) described these arrangements as a negative by-product of ‘incomplete decentralization’. Indeed, the provision of emergency humanitarian assistance could be construed as an example of an ‘unfunded mandate’, which has been shown across the world to have adverse effects on economic growth (Rodríguez-Pose and Vidal-Bover 2022). Delegating responsibility over a policy area like humanitarian assistance without adequate resources potentially undermines the legitimacy of the local level. This seems paradoxical given that decentralization is a cornerstone of Colombia’s 1991 Constitution. It was intended to “consolidate democracy, develop a direct and participatory democracy, and to increase governability” (Ibáñez and Velásquez 2008). Political decentralization came first with the direct election of mayors and governors, then financial decentralization also prompted by local levels, and much later administrative decentralization pushed by the national level (Falleti 2010). This is relevant to internal displacement because decentralization sought to respond to structural issues underlying the conflict such as unequal political representation, landgrabs by agribusiness, and uneven local revenues (Ballvé 2012; Ch et al. 2018; Steele and Schubiger 2018). But existing spatial differences affected both internal displacement and its response. Underlying disparities in the economic development of Colombia’s regions (Franz 2019) affect the revenues and capacities available for administering welfare services (Vidal et al. 2013).

Political incentives to respond to displacement also vary by municipality. Vidal et al.’s comparative study (2013) demonstrates improved clarity on roles and responsibilities between 2008 and 2011. But this did not solve key issues and, in fact, increased tensions as municipalities could still not fulfil their roles. The study compares the responses to internal displacement in the cities of Bogotá and Cali, the former hosting of the majority of the internally displaced in the country and the latter serving as the main place of refuge for most people fleeing violence in the southwest. It found that politics in each of the cities mattered; the more leftist leadership in the capital enabled spending local revenues on programmes for those internally displaced. By contrast, the centre-right city of Cali faced greater political pushback internally and struggled to maintain regular contact with national government actors from a different political party. However, local politics had a marginal impact, as both cities faced substantial resource gaps that were difficult to overcome, even with the capital’s greater administrative capacity and resources. Though local politics matter, this comparison suggests that a lack of dedicated funds for the response outweighed other hindrances.

The national level tried different approaches in the past to require municipalities to budget for emergency humanitarian assistance and other programs. Law 1190 passed in 2008 uses firm, almost coercive language to oblige the local and regional levels to meet their responsibilities. The national-level agencies must intervene, taking actions that “guarantee commitments from the territorial entities for the fulfilment and materialization of the people displaced by violence in their respective jurisdictions” (Colombia: Congress of the Republic 2008, Art. 2; emphasis added). Local response plans were made obligatory, though there was arguably little the national level could do to sanction local entities if the plans were not followed. A year later the constitutional court was given authority to grant certificates to reward municipalities for implementing their plans as a form of soft incentive (Vidal et al. 2013, p. 3). By contrast, the Strategy takes a new approach by reaffirming the local level’s responsibility for the protection of human rights and places limits on subsidiarity. The language of co-responsibility is thus a reminder to the local level of their existing obligations. It enables the national level to skirt decentralization issues and hence limit the resources it spends on emergency humanitarian assistance. But the result is that structural issues underpinning coordination challenges and disparities in responses remain largely unresolved.

Technocratic Action-Planning Process

The problem that the Strategy responds to is one of ‘coordination’. Instead of addressing the highly political and/or budgetary challenges presented by local actors, the Strategy focuses generally on ‘which level does what and when’. This presumes the clarification of roles and responsibilities and the alignment of planning processes will bring all levels onto the same page in fulfilling their obligations in an efficient and timely manner.

How the Strategy chooses to do this depicts a practice of technocratic problem-solving. This technocratic approach is apparent in other features of the internal displacement response, especially its reliance on indicators to measure progress. Urueña (2012) frames this as a Colombian drive towards “rationalizing administrative action… a never-ending quest to achieve efficient bureaucracies, where technocrats would populate the administration, and exercise power rationally and predictably” (p. 277). This stems from new public management approaches that prioritize efficiency and transparency in decision-making. This also reflects a history of incorporating ‘good governance’ principles introduced and at times imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund on Latin American governments as part of its neoliberal interventions in the 1990s (Zurbriggen 2011; Franz 2019). The Strategy demonstrates its technocratic ideology through the planning process it formalizes. I say ‘formalizes’ rather than invents because a similar process had been used by some municipalities, called the Plan Integral Único, since 2004 (Acción Social 2008; Lopera Morales et al. 2009), with varying degrees of success and investment.

The Strategy establishes a process by which the municipalities formulate their action plans (Plan de Acción Territorial). By standardizing this process, the Strategy regulates the behaviours and expectations of the local level. The action plans must include the local entity’s programs and projects with the resources they set aside for this (Colombia: President of the Republic 2015, Art. 2.2.8.3.1.5). This is to prevent the action plans from becoming a long ‘wish-list’ of desired programming that cannot be budgeted for (Procurador General de la Nación 2019, p. 391), which has been highlighted as a problem in the past (Ibáñez and Velásquez 2008). Based on the review of those action plans, the national level can assess several things: the need for intervention and joint programming, specific projects to co-finance, needs of the population, and capacities of the municipalities to respond.

Evaluating these plans combines a rights and needs-based logic. Emergency humanitarian assistance is framed as restoring the rights of its residents to have their minimum subsistence needs fulfilled (Alcaldía de Bogotá 2018). The action plan must therefore explicitly respond to the gaps in fulfilling these rights (these are the ‘needs’). These are quantified by indicators for the ‘effective enjoyment of rights’ (Goce Efectivo de Derechos). Depending on the extent to which a person meets certain indicators, how recently a person was displaced, and whether they have been registered in the official government registry, a person may be eligible for one of three aid packages from the municipality.12

These are urgent humanitarian aid (Ayuda Humanitaria Inmediata), emergency humanitarian care (Atención Humanitaria de Emergencia), and transitional humanitarian aid (Ayuda Humanitaria de Transición) (Alcaldía de Bogotá 2018, p. 8–9).

This includes not just the official government registry administered by the Victim’s Unit but also input from the annual socioeconomic household surveys administered by the National Planning Department (SISBEN).

The reporting process for these action plans is a form of coordination. Action plans must be shared with the national level within certain timeframes, in the format of a log-frame style template called the Tablero PAT. The Tablero PAT guides the municipalities to put all relevant information into a consistent format to aggregate the action plans into a ‘unified report’ (Reporte Unificado del Sistema de Información, Coordinación y Seguimiento Territorial). This serves as a tool for the Victim’s Unit to monitor and evaluate overall progress in the response. This process becomes a vertical form of communication between the local and the national-level entities. This communication reaffirms hierarchies because it is not a two-way dialogue; there is no mandated space for verbal exchange or debate on the subtleties of the local context and possible resource constraints faced.

Capacity-Building and Joint-Funding Opportunities

The action-planning process must adapt to the mixed capacities of municipalities. This again sidesteps political issues and favours a technical solution. The Strategy addresses the underlying disparity between regions by offering limited funding for joint-initiatives and training to the municipalities that need it. One function of the Tablero PAT is to identify the municipalities in which the documented needs exceed the resources available, meriting some help from other levels. The national level considers the following criteria when deciding whether to intervene:

the capacity of the local entities, the dynamics of the conflict and the conditions of the population of victims, and additionally they will consider the information submitted by the local entities and the information that the national entities themselves have available (Colombia: President of the Republic 2015, Art. 2.2.8.3.1.15).

The local entities would need to make a strong case through their Tablero PATs for relinquishing any responsibility for implementation. Even then they may not have their requests met, for example if the information available to the national entities does not correspond to that which has been submitted by the local level. The counter is also possible; the national-level monitoring may reveal that some municipalities indeed have “the capacity for investment and a high number of victims, that yet do not allocate resources for their attention”. These would be reported to the Ministry of the Interior and the Victim’s Unit “as an input for the development of the plans for improvement of the local entities” (Colombia: President of the Republic 2015, Art. 2.2.8.3.1.23). This describes what the national level would consider ‘misbehavior’ showing that the process altogether serves to self-regulate the local entities, sanction them if needed, and gives the national level the final determination on where and to what extent they should intervene.

The process of developing the action plans and Tablero PATs can be considered as a self-reported capacity assessment by the local entities. Both their ability to adhere to the process and the action plans’ content—the budgets and plans presented and how well these can be expected to respond to needs—make their ‘capacity’ legible. The Strategy interestingly does not define ‘capacity’. Instead, it gives the Ministry of the Interior and the Victim’s Unit the authority to “design a strategy for local intervention to offer tailored technical assistance to the local entities” (Colombia: President of the Republic 2015, Art. 2.2.8.3.1.19) which “should be holistic and address the particularities, potential and necessities of each local entity”. The Strategy thus establishes new practices for capacity building. The Interinstitutional Technical Assistance Team (Equipo Interinstitucional de Asistencia Tecnica Territorial) is charged to carry this out. This Team is a sub-directorate of the Victim’s Unit and has increased its activities every year since the Strategy came out. For example, in 2020, it conducted “35 days of technical assistance… that assisted 805 municipalities and 31 departmental governments” (Victim’s Unit 2021c). In this way, framing ‘low capacity’ as a key problem to be fixed, the Strategy flags a technical solution, namely training.

These three tactics attempt to overcome the impasse between national and local levels. While the national level is still the agenda setter (Lukes 2004), this compromise importantly leaves some space for local autonomy by leaving it fairly open how the local entities are expected to arrive at their decision-making. The local entities can tailor their specific plans as they see fit, within the parameters set, and if the plans ‘meet the needs’. Indeed, the process of developing the plans themselves may yield political benefits, as in the city of Medellín, where the precursor to the action-planning process was piloted (Lopera Morales et al. 2009). This process brings some legitimacy to local level actors (Lopera Morales et al. 2009). It can also benefit local governments either by supporting horizontal multilevel governance, expanding networks with non-state actors, or by supporting vertical multilevel governance under certain conditions by giving them space to assert their value to the response overall. This is exemplified by the Bogotá action plan describing in detail how their adherence to the Strategy affirms their “effective articulation” with the national level entities (Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá 2019, p. 26) and “convert[s] Bogotá into a reference of peace and reconciliation” (Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá 2016, p. 6). In this way, Bogotá links their response to victims with the city’s identity. Indeed, local and regional identity is a key though underexplored factor affecting engagement in multilevel governance structures (Kleider 2020).

However, the same difficulties that differentiate poorly from well-resourced municipalities likely affect their ability to participate equally and adequately in these processes, and therefore their potential to benefit politically from them. A monitoring commission convened by the Office of the Attorney General claimed that even four years after the adoption of the Strategy, the processes and tools it formalized have not (yet) managed to overcome the ‘structural deficiencies’ that the Strategy was developed to address (Procurador General de la Nación 2019, p. 398). This points to possible limitations but also demonstrates the high stakes and expectations for this System of Co-responsibility.

Conceptualizing Multilevel Governance in Colombia’s Response

This section considers how to adapt the multilevel governance of migration literature to internal displacement responses. I argue that this requires explicit discussion of the power dynamics within multilevel governance structures and policies. Doing so helps to demonstrate the absence of vertical power rebalancing opportunities within Colombia’s response. The System of Co-responsibility potentially enables the redistribution of power at the local level rather than between local, regional, and national levels.

First, I adapt a conceptual framework from Peter Scholten’s work to better account for power dynamics. I will then demonstrate how a certain kind of multilevel governance is prioritized over others in Colombia’s response, namely horizontal relations at the local level.

In applying multilevel governance to migration challenges, Scholten’s (2013) framework outlining various ‘modes of governance in multi-level settings’ has become a reference point. He argues that it is critical to view multilevel governance within a context of various ideal-type modes of governance in multilevel settings. Only one of these ideal types is the ‘cooperative’ mode of governance that we commonly associate with discourse on multilevel governance (Spencer 2018). The other three modes are top-heavy governance (‘centralist’), bottom-heavy governance (‘localist’) or a situation in which interests between levels are completely at odds and conflict is imminent (‘decoupled’).

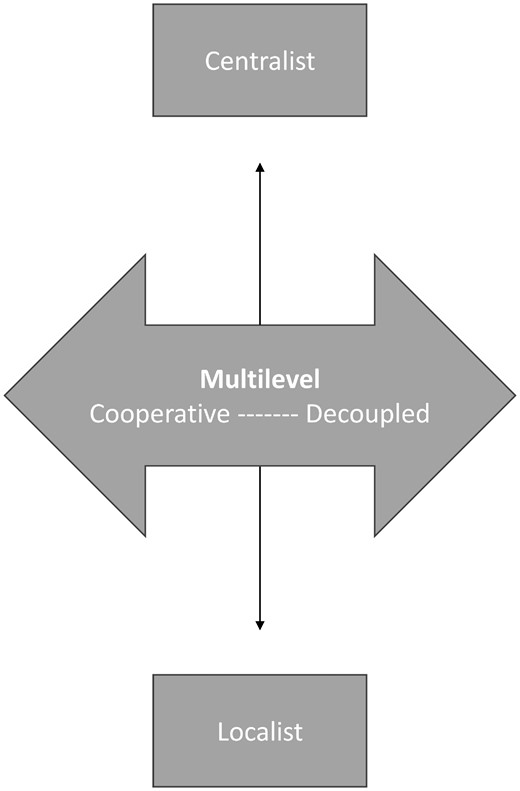

Building upon this typology, I propose to visualize how these different modes relate to one another. Specifically, I suggest locating the different modes of governance on a spectrum between centralist and localist. For these two modes, the locus of decision-making is agreed-upon and clearcut. Anything in between is subject to bargaining, negotiation, and power-sharing between levels and hence represents multilevel governance. Figure 1 shows these associations.

Relationships between Modes of Governance in Multilevel Settings

I furthermore propose that both cooperative and decoupled modes of governance be considered as part of a broader category of multilevel governance. Indeed, both modes imply bargaining and negotiation among the institutions and actors involved, albeit with different policy results.14

These conform to Caponio and Jones-Correa’s (2018) ‘minimum conditions’ for considering a specific policymaking arrangement to be an instance of multilevel governance. These are that the arrangement challenges vertical, state-centered formal hierarchies, that there is interdependency among actors such that no one actor can design or implement the policy alone, and that power-sharing terms are not fixed, e.g. there is bargaining and negotiation between the actors involved.

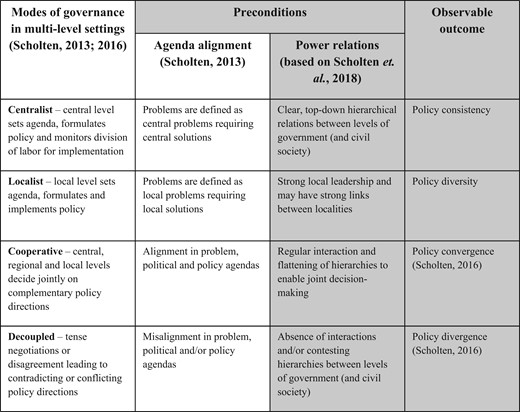

Going deeper into cooperative multilevel governance, I bring various conceptual contributions from Scholten and others together to show certain conditions that enable this form of multilevel governance to emerge. Figure 2 summarizes Scholten’s four ‘modes of governance’ in the lefthand column (Scholten 2013) and builds from this in the shaded areas.

Modes of Governance in Multilevel Settings. Adapted from Scholten (2013, 2016) and Scholten et al. (2018). The Shaded Areas Indicate the Author's Interpretation Building from These Different Studies

Scholten (2013) theorizes that the conditions for cooperative decision-making arise when: (1) the multilevel character of a policy problem is explicitly recognized and (2) actors operating on different levels align their problem, political, and policy agendas. This means aligning the issue at stake, the political feasibility and benefits of addressing the issue, and the institutional incentives and capacity to address the issue. Alignment of these agendas can lead to policymaking processes that result in ‘policy convergence’, or a suite of policies that create a ‘division of labour’ (Scholten 2016, p. 978) to respond to the same problem in complementary ways.

Assessing how this convergence occurs is key for understanding the strategies that different levels of government use to create the conditions for multilevel governance. In general, the quality and quantity of interactions between levels must be sufficient for a variety of actors to align their agendas and agree on how to collectively solve a problem. These interactions can be informal or formal, but the opportunity must be created deliberately. In other words, “specific venues or forums are required for vertical interaction and cooperation” (Scholten et al. 2018, p. 2014). These opportunities for interaction also do not necessarily originate from the national level. Scholten et al. (2018) provide the example of a shift from localist towards a cooperative multilevel governance in migrant integration policies in the Netherlands. Yes, acceptance of cooperative multilevel governance was triggered by a leadership change at the national level, but this was in recognition of the contributions that municipalities were already making. They had demonstrated their concerns and expertise in this policy area through a practice of local entrepreneurship (Scholten and Penninx 2016) and lobbying different levels of government on various aspects of migrant integration, a strategy called ‘vertical venue shopping’ (originally described by Guiraudon 2000). This led to ‘intensive contact between the municipalities of Rotterdam, The Hague, Westland and the Ministries of Social Affairs and Internal Affairs’ (Scholten et al. 2018, p. 2024), eventually creating formal collaborative structures to organize their work. These ‘vertical’ national-local collaborative structures created policy that was eventually adopted by the national level. Their policy work was more attuned to the local specificities of the different municipalities participating in the process. In this way, a cooperative form of multilevel governance emerged because of initiatives from both above and below.

But more than that, they were enabled by a redistribution of power within these policymaking structures. I define these power relations not just as the extent of interactions between different levels of government but also as the widening or flattening of hierarchies in decision-making within those interactions. These power relations can be shaped by municipalities, for example through building alliances between different municipalities to strengthen their negotiating position with national governments (Ataç et al. 2020), or even by civil society, for instance to encourage interdependence between municipalities and local non-governmental organizations (Spencer 2018; Polat and Lowndes 2022). I therefore expand on Scholten (2016) and Scholten et al. (2018) to argue that agenda alignment and power relations interact to shape the governance mode. These create different observable policy outcomes; in addition to policy convergence and divergence discussed by Scholten, I add policy consistency from centralist modes and diversity from localist modes.

The System of Co-responsibility creates important but limited conditions for cooperative multilevel governance. The principle of subsidiarity should make the distribution of emergency humanitarian assistance a decidedly localist policy area. But decades of negotiations demonstrated that this did not enable local action in many municipalities, especially those far from Bogotá and with sparse local revenues. Introducing the action planning process alongside capacity building creates certain kinds of interactions between levels. This includes regular interaction based on annual reporting timelines, but not necessarily the flattening of hierarchies between levels of government. Working as designed, the processes incentivize local responses through alignment in problem-framing and policy agendas. This goes far beyond the soft incentive of a court-issued certificate of compliance that existed before; however, there seems to be nothing in the Strategy itself that promotes the alignment of political agendas between levels.

It is possible that this happens through other mechanisms. First, the Strategy establishes a platform for horizontal multilevel governance that can bring a crucial infusion of capacity from other non-state actors. It gives one local-level entity, the Local Committee for Transitional Justice (Comite Territorial de Justicia Transicional), power over the municipality in its role to approve the local plans and conduct follow-up monitoring. Each of the municipalities has its own such committee that brings together local government, civil society organizations, and service providers to coordinate responses at local levels. It also has the important function of liaising with victim’s advocacy groups, which could increase political pressure for prioritizing the response (Lemaitre and Sandvik 2019). But this is a slow process of building coalitions and increasing civic participation. Indeed, shifting political incentives is a longer-term endeavour, much more complex than introducing new technocratic processes and practices. Second, local leadership may play an important role. Ibáñez and Velásquez (2008) remarked that the leadership of mayors and other local officials was crucial in this policy area. This continued to be a priority for the Victim’s Unit nearly ten years later. After the 2016 local elections, the Victim’s Unit developed detailed guidance to explain the rights of victims specifically for newly elected municipal officials. While not a guarantee, targeted guidance could serve as a pathway towards aligning political agendas to enable a cooperative (vertical) multilevel governance in addition to a nascent horizontal one.

Conclusions

The Strategy of Co-responsibility responds to demands for clarity on roles and responsibilities in the provision of emergency humanitarian assistance, the first step in restoring basic rights to those internally displaced due to Colombia’s longstanding internal armed conflict. To do this it provides a normative framework for applying the principles of decentralization, emphasizing joint responsibility for the protection of human rights, and limiting subsidiarity. This regulates and puts pressure on municipal authorities to act in the absence of other incentives.

Other tactics that the Strategy of Co-responsibility uses to nominally respect local autonomy while nudging compliance from the local level are the formalization of an action-planning process and combining capacity building with joint-funding opportunities. I demonstrated how these are depoliticized and presented as technical solutions, enabling the Strategy to sidestep the call to further decentralization through the internal displacement response. Frameworks and examples from the multilevel governance of migration reveal possible alternatives for producing policy convergence and complementarity between levels. These require acknowledging and rebalancing existing power asymmetries and aligning political agendas. This is, however, a long-term endeavour.

The analysis of the System of Co-responsibility reveals the benefits and limitations of coordination policies ‘from above’. In general, the System reproduces existing hierarchies of a unitary government; subnational governments do not (yet) have power to influence the overall structure of the response to internal displacement. But it does respect local autonomy by at least discursively encouraging local ownership of the response, and by introducing incentives for horizontal multilevel governance. In general, this reveals that resource allocation within internal displacement responses is a highly contentious issue in contexts severely affected by conflict. The multilevel governance structures likely cannot solve the bigger structural issues of uneven economic development and governance capacity. But if roles and responsibilities are clear and support is available in poorly resourced areas, then cooperative multilevel governance in the response to internal displacement can gradually increase trust between levels of government. This has the potential to improve coordination and governance more widely.

Asking what the multilevel governance literature means for forced migration contexts and vice versa opens a variety of new avenues for research. This research corroborates Polat and Lowndes’ findings that multilevel governance “need not imply any weakening of the state or any empowerment of local actors. Rather, MLG denotes increased complexity… and the presence of new central government control strategies” (2022, p. 68). This suggests useful comparisons between the governance of internal displacement and refugee responses. This research also serves as a starting point for comparative analyses of internal displacement responses in federal and unitary but decentralized contexts of conflict-induced internal displacement.

For policymakers, multilevel governance frameworks inform proposals for strengthening a ‘whole-of-government’ approach to internal displacement responses (UN Secretary General 2021). Though central to the final report of the United Nations High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement, it remains unclear what engaging all levels of government means (and costs) in practice. A Cross-Regional Forum on Implementing Laws and Policies on Internal Displacement convened in June 2023 by the Special Rapporteur for the Human Rights of IDPs, UNHCR and the Global Protection Cluster brought together ten governments facing internal displacement to discuss this exact question. Colombia may provide a model to follow with the compromise it conceives as co-responsibility. But I propose that confronting the multilevel dimensions of internal displacement and the power dynamics within internal displacement responses alongside Scholten’s framework could contribute meaningfully to implementation debates. Finally, for practitioners, strategies for aligning problem, politics and policy agendas generates ideas around how to encourage collaboration among stakeholders in a highly politicized context.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the detailed review from Dr Ileana Nicolau on a late draft of this paper. I am also grateful for the feedback provided by the Urbanisation, Planning and Development research cluster at the London School of Economics in their ‘Writing the World’ human geography seminar. I would also like to thank Dr Romola Sanyal and Dr Nancy Holman for reviewing early drafts. This article benefitted from methodological discussions with Dr Erica Pani, Dr Edward Ademolu, and Dr Ana Mosneaga, as well as research and translation support from Santiago Bolaños Signoret. I also appreciate the time, engagement, and helpful comments from two anonymous reviewers and the editor, all of which have improved the quality of the article.

Funding

This research was supported by a PhD Studentship on Analysing and Challenging Inequalities, awarded and managed by the International Inequalities Institute and funded by the London School of Economics and Political Science.