-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David Ongenaert, Claudia Soler, Beyond victim and hero representations? A comparative analysis of UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies for the Syrian and Ukrainian crises, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 37, Issue 2, June 2024, Pages 286–306, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feae035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The Ukrainian crisis has received substantial Global Northern policy support and favourable news coverage, contrasting sharply with Global Southern crises. Nevertheless, refugee organizations can influence public perceptions through social media. This study comparatively analyses UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises (2022–2023). Applying a multimodal critical discourse analysis on UNHCR’s Instagram posts (N = 90), we discern interacting humanitarian and post-humanitarian appeals, involving inter- and intra-group hierarchies of deservingness, expanding research on humanitarian communication. While UNHCR mainly represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians as victims and focuses on ‘ideal victims’, it mostly portrays forcibly displaced Syrians as empowered individuals, likely due to context-specific differences and partially countering news and policy narratives. Both humanitarian representations often intersect with post-humanitarian strategies, facilitated by Instagram affordances. This study thus contributes to the literature on humanitarian communication with comparative crisis-specific and platform-specific insights and causes. Moreover, it nuances the often-assumed importance of post-humanitarian imageries on social media.

Introduction

The Ukrainian-Russian war has led to one of the largest crises of modern times, involving 11.6 million forcibly displaced Ukrainians at the end of 2022 (UNHCR 2023). Many European countries, including those with anti-migration sentiments, are promoting solidarity with Ukrainian refugees. This is illustrated by the European Union’s (EU) first activation of the Temporary Protection Directive since its adoption in 2001, which prioritizes prompt and efficient assistance rather than individual asylum application processing. This approach contrasts sharply with the EU’s much more restrictive policies towards refugees from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including Syria (Moallin et al. 2023). Similarly, Western news media often portray forcibly displaced Ukrainians more positively as contingent, legitimate, innocent and/or resilient victims, while those from the MENA as passive victims and/or threats, constructing hierarchies of deservingness. Various media have bluntly justified these double standards by arguing that Ukrainians resemble more their host populations: European, Christian, and white (Zawadzka-Paluektau 2023).

In these challenging contexts, international refugee organizations often play important roles. They provide humanitarian assistance and protection (Betts et al. 2012) but also increasingly attempt to inform and influence media, public, and political agendas through public communication (Green 2018). However, international refugee organizations face acute dilemmas about how to deal with and communicate the above-mentioned double standards on refugee protection and tensions with humanitarian priorities and principles (e.g. impartiality and neutrality) (Moallin et al. 2023). This raises the question of whether and how they use different communication strategies for different crises. So far, various studies have analysed how international refugee organizations portray forcibly displaced people from the Global South and mostly identified ‘victim’ and ‘hero’ representations (Ongenaert 2019; Veeramoothoo 2022). However, humanitarian representations of forcibly displaced people from the Global North, including Ukraine, have barely been explored.

Furthermore, the focus has mainly been on reports (Veeramoothoo 2022), photo archives (Bellander 2022), and press releases and news stories (Ongenaert and Joye 2019; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). However, refugee organizations’ social media strategies, including on Instagram, have hardly been investigated. Nevertheless, refugee organizations increasingly utilize social media to inform, sensitize, advocate, mobilize, and raise funding (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018). These platforms provide new opportunities for broader visibility, interactivity, more nuanced representations, and challenging ingrained hierarchical societal structures (Scott 2014). Hence, refugee organizations’ social media strategies can significantly influence public perceptions of migration. Especially as social media discourses may affect conventional media’s coverage priorities, which often follow social media trends (Yang and Saffer 2018). Particularly Instagram has gained substantial popularity for social justice discourse, partially due to its rapid development and significance to aesthetic photos (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018).

Acknowledging the above-mentioned trends, we apply a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) (Machin and Mayr 2023) on the Instagram posts (N = 90) of the leading refugee organization United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) about the Syrian and Ukrainian crises in the key period between February 2022 and March 2023. This study investigates what are the main Instagram communication strategies used by UNHCR for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises? We examine whether and how UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies differ from previously identified humanitarian narratives on traditional communication channels and differ for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises. Hence, we respond to the need for more comparative research on this subject (Ongenaert et al. 2023b).

This study reveals mixed results as UNHCR employs interacting humanitarian and post-humanitarian appeals, involving explicit and implicit inter- and intra-group hierarchies of deservingness and crisis-specific differences and commonalities, extending and nuancing earlier research. While UNHCR primarily represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians as victims and highlights ideal victims, it mostly portrays forcibly displaced Syrians as empowered individuals. These representations partially counter common news narratives and can likely be explained by context-specific differences (e.g. different crisis phases and geographical locations) and objectives. Further, both humanitarian appeals often interact with post-humanitarian appeals, which are facilitated by Instagram affordances. Overall, we argue that UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies largely reproduce humanitarian and post-humanitarian strategies. Following challenging institutional and crisis-specific contexts and dominant social media logics, UNHCR barely utilizes the platform’s opportunities for more nuanced, contextualized representations. This study contributes to the literature on humanitarian communication by providing in-depth, comparative insights into the largely unexplored social media strategies of refugee organizations for both Global Southern and barely examined Global Northern crises. It provides comparative crisis-specific and platform-specific insights and potential underlying causes and demonstrates that mainly humanitarian imageries, frequently in interaction with post-humanitarian imageries, are used on Instagram, which nuances the often-assumed importance of the latter on social media. We first discuss the underlying challenging sociopolitical and corporatized contexts in which refugee organizations operate and then elucidate their communication strategies and social media challenges and opportunities.

Challenging sociopolitical contexts

Although providing protection and assistance is primarily the duty of states, several countries are increasingly reluctant to cooperate with refugee organizations, have tightened their asylum policies and rarely provide sufficient humanitarian funding (Betts et al. 2012). These measures have made it increasingly challenging for refugee organizations to achieve their goals (Walker and Maxwell 2009).

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic, the worldwide recession, the climate crisis, and widespread negative public opinions on forcibly displaced people from the Global South have significantly complicated their operations. Popular populist movements attempt to criminalize and fuel public discontent with forced migration, often on social media (Yang and Saffer 2018). Moreover, news media often portray forcibly displaced people as passive victims and/or threats (Chouliaraki 2012a) and usually limit their voice in the public debate, favouring politicians and governmental officials as the dominating news sources (Franquet Dos Santos Silva et al. 2018). Further, the humanitarian competition for funding and criticisms of the limited transparency and accountability of humanitarian organizations have further challenged refugee organizations’ goals (Vestergaard 2008). Given the growing role of both UN agencies and NGOs in addressing global challenges, there are rising expectations of transparency and accountability of their operations towards donors, taxpayers, and affected people. They should therefore promote accountability and transparency, relying on high-quality, culturally inclusive, learning-based management (Clarke 2021).

Considering these challenges, refugee organizations must create successful communication strategies to sensitize, inform, build agendas, and fundraise (Yang and Saffer 2018; Ongenaert and Joye 2019). Refugee organizations are simultaneously adapting their communication practices to corporatization trends in the humanitarian industry.

The corporatization of the humanitarian industry

Following trends of professionalization and commercialization, humanitarian organizations increasingly adopt branding practices, allowing them to communicate their values more explicitly and generate new types of legitimacy (Vestergaard 2008). In short, non-profit branding concerns the deliberate, active management of both tangible and intangible perceptions to communicate consistent and coherent messages to stakeholders (Hankinson and Rochester 2005). A positive non-profit brand image often increases fundraising (Paço et al. 2014).

Similarly, celebrity humanitarianism has been promoted within humanitarian organizations as it enables larger visibility, brand awareness, and fundraising (Mitchell 2016). Importantly, the engagement of celebrities in humanitarianism is not new but celebrity humanitarianism transcends mere advocacy through branding. This results in mutually beneficial alliances between humanitarian organizations and celebrities. While celebrities’ reputations as humanitarians are legitimized, humanitarian brands obtain increased exposure (Chouliaraki 2012b).

The integration of these corporate practices, interests, and values indicates the corporatization of humanitarianism and has blurred public–private sector divisions (Vestergaard 2008). Critics argue that by adopting a marketing logic, humanitarian organizations prioritize in their communication consumers’ interests, identities, and values over their cause and thus support existing values rather than social change. Therefore, humanitarian branding is sometimes considered to contradict the principles of charity, voluntarism, democracy, and grassroots activism (ibid.). Given the corporatization of humanitarianism, the types of humanitarian communication strategies have changed, especially on digital platforms.

Humanitarian communication strategies

We discuss the main communication strategies applied by humanitarian organizations, including refugee organizations, through Scott’s (2014) typology. Essentially, humanitarian organizations mainly use various humanitarian discourses, including shock effect appeals and deliberate positivity (infra), which morally justify solidarity on human vulnerability by relying on a universalist common, shared humanity, across political and/or cultural differences. However, Chouliaraki (2012a) observed gradual, non-linear shifts from these humanitarian discourses to post-humanitarian discourses. These respond to ‘existing concerns about the moral deficit of ‘common humanity’ as a justification for solidarity, by moving away from the refugee and towards the self as the primary object of our cognition and emotion’ (ibid.: 13). These rely on a morality of contingency, involving the ‘Self’ as a moral justification for solidarity with distant suffers, particularly on digital media.

Shock effect appeals

Humanitarian organizations traditionally use shock effect appeals, which address the suffering of affected people. They usually portray people as innocent, powerless people who deserve compassion and help (Scott 2014) to generate strong emotions such as pity and guilt among audiences and eventually media, public, and political attention and support (Chouliaraki 2010; Ongenaert et al. 2023a). There is often a focus on women and children, who are considered ‘ideal victims’ (Höijer 2004; Jhoti and Allen 2024). Through their apparent innocence and vulnerability, they are usually more effective in generating pity and eventually audience engagement and fundraising than other population groups (Moeller 1999; Johnson 2011). However, as the circumstances of others or the context and nature of the larger cause are not considered, this focus can diminish public engagement in humanitarian causes and lead to public perceptions that some victims deserve more compassion and assistance than others, creating hierarchies of deservingness among distant suffers (Scott 2014).

Nevertheless, shock effect appeals are often the most effective in generating awareness and financial support, especially for humanitarian emergencies (Scott 2014). International refugee organizations have therefore widely adopted this communication strategy. Forcibly displaced people’s humanitarian images have generally changed from heroic, politicized individuals in the Cold War period to anonymous, voiceless, depoliticized, dehistoricized, decontextualized, universalized, racialized, and/or victimized masses from the ‘Global South’ (Ongenaert 2019; Bellander 2022; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). These discursive transformations interact with the aforementioned policy shifts and serve to mobilize public support and manage forcibly displaced people’s perceived threats. These representations contribute to frequently oversimplified crisis and emergency discourses which, driven by financial and media interests, emphasize the severity of humanitarian situations (Johnson 2011).

However, the repeated use of these appeals can make audiences desensitized to images of suffering, also known as ‘compassion fatigue’ (Moeller 1999; Chouliaraki 2010). This entails both practical and ethical risks. It can create a sense of powerlessness and lead to less involvement. Since these appeals attempt to arouse guilt, this can generate frustration and resistance to campaigns. Rather than promoting social action for humanitarian causes, these risks could undermine it (Chouliaraki 2010). Moreover, humanitarian organizations could inadvertently reinforce white saviour stereotypes by implying that Northern donors are key to societal issues in the Global South. Furthermore, these appeals address suffering victims, benefit from them, and often neglect or oversimplify the complex contexts and root causes of suffering (Scott 2014).

Deliberate positivity

In pursuing more representative and dignified communication strategies, humanitarian organizations began to adopt deliberate positivity, favouring the agency and dignity of affected people (Chouliaraki 2010). It seeks to induce feelings of gratitude and empathy through images that subtly convey affected people’s gratitude to donors (Chouliaraki 2010; Scott 2014). Refugee organizations often represent forcibly displaced people as ‘heroes’; as empowered, optimistic, resilient, and humane individuals, highlighting their voices, emotions, and names (Rodriguez 2016; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). They frequently represent forcibly displaced people as entrepreneurs or talented people (Turner 2020; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). This positive imagery aims to engage audiences through identification and relatedness and to demonstrate the relevance of donating, often to eventually encourage (further) donating (Ongenaert et al. 2023a).

However, deliberate positivity often highlights talented, prosperous and/or engaging individuals and fails to address broader systemic issues (Chouliaraki 2010; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). It may also inadvertently create a dependency on external assistance. Given that donations are promoted to facilitate positive change in the Global South, this may further strengthen the dependence on existing unequal North-South power relations, rather than promoting self-reliance and empowerment (Scott 2014). Finally, highlighting positive progress can appear as if active support is no longer necessary (Chouliaraki 2010; Scott 2014).

Post-humanitarian appeals

In recent years, humanitarian organizations increasingly employ post-humanitarian appeals. Post-humanitarian communication uses creative text and visual techniques, emphasizing discourses centred on Western audiences rather than distant suffers, who are often completely absent (Scott 2014). Relying on celebrity humanitarianism and online donation actions, this strategy can realize brand differentiation, attract niche customers or influence global policy (Scott 2014; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). Hence, refugee organizations represent forcibly displaced people in creative, innovative, and aesthetic ways and engage in celebrity humanitarianism, particularly on digital and social media (Chouliaraki 2012a; Mitchell 2016). Celebrity humanitarianism can increase the visibility of humanitarian issues, reach and engage wider, previously unconcerned audiences, and foster emotions of belonging and connection (Mitchell 2016).

However, celebrity humanitarianism will mainly generate public discussion about the celebrity rather than educating the public about systemic change (Chouliaraki 2012b). Celebrity humanitarianism and branding also create moral conflicts by staging human misery in the fields of entertainment and consumerism (Vestergaard 2008). Post-humanitarian appeals have been criticized for depriving affected people of their voice, reproducing North-South power imbalances (Scott 2014), and relying primarily on own moral judgements to engage with suffering people (Chouliaraki 2010).

Social media opportunities and challenges for humanitarian organizations

Audiences and social media in a humanitarian context

We consider audiences in the digital networked age as relatively active. They engage, interpret, negotiate, and critique media texts. Whereas once people used temporarily media for specific purposes, they are currently continually and unavoidably audiences, as all aspects of social reality are mediated or mediatized (Hepp 2013). However, there are simultaneously substantial digital divides (Scheerder et al. 2019). Moreover, audiences are diverse and interpret polysemic news differently. For instance, the frequency and the tone of news on immigration, contextual factors (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart 2009) and citizens’ media consumption, media trust, and coverage evaluation strongly shape public opinions on immigration (De Coninck et al. 2018). Audiences’ responses to mediated distant suffering are thus diverse and mediated by media texts and their sociodemographic positions, biographical scripts and broader national and cultural contexts, and discursive frameworks (Kyriakidou 2022).

To reach, inform, sensitize, and engage audiences, social media has become crucial for humanitarian organizations, including refugee organizations (Kim 2022). They provide potent, affordable platforms for showcasing organizations’ efforts to large audiences (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018). By enabling two-way communication and immersion in virtual worlds, social media might help reduce the gap between audiences and affected people. Social media allows for more nuanced, varied, and comprehensive representations of the Global South and provide simpler options for action (e.g. exchanging information, signing online petitions), increasing participation levels (Scott 2014; Rosa and Soto-Vásquez 2022). Hence, many NGOs utilize popular social networks (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018). However, there are also risks. Aesthetic visual representations of humanitarian issues could become more relevant than the issues themselves and the demands for action (Chouliaraki 2010). Furthermore, editing images to meet public and aesthetic ideals can create distance between the represented and the audience and distort everyday life realities (Woods and Shee 2021). Moreover, the simplicity of participation may give the appearance of commitment but can foster short-term, superficial engagements in humanitarian issues (Scott 2014).

Instagram affordances and aesthetics

Particularly Instagram has gained popularity for social justice communication (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018). An important advantage is the convincing ability of visuals. Images are more memorable and understandable than texts, attract more attention (Knobloch et al. 2003) and are perceived as more reliable because they are mostly seen as an accurate representation of reality (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018). However, to achieve stakeholder engagement on social media, refugee organizations’ posts should also reflect, besides stakeholder interests and principles, social media logics (Yang and Saffer 2018). In short, social media logics refer to the norms, strategies, mechanisms, and economies through which social media platforms process information, news, and communication and channel social traffic (Van Dijck and Poell 2013). ‘[E]ach social media platform comes to have its own unique combination of styles, grammars, and logics’, or ‘platform vernacular’ (Gibbs et al. 2015: 257). These genres of communication result from the affordances of social media platforms and users’ appropriations, mediated practices, and communicative habits. These vernaculars evolve over time and through design, appropriation, and use (ibid.).

Organizations need to design their posts attractively as aesthetics are important on Instagram. Instagram aesthetics can be situated at the levels of Instagram’s visual and textual content, practices and users. It includes visual aesthetics, including genres and tropes of content and visual aesthetic normalization, users’ practices and norms, and audiences and their motivations for using Instagram (Leaver et al. 2020). Central to Instagram’s vernacular and aesthetics are the affordances for photo-sharing, tagging images, creating captions and texts, applying photographic filters, and mobile phone usage as well as their interplays. These enable Instagram to be embedded in everyday practices and function as a space to present one’s life and get informed and learn about others’, including both mundane and extraordinary experiences (Gibbs et al. 2015; Leaver et al. 2020). In that regard, ‘Instagramism’ refers to the aesthetic strategies employed in the construction of aesthetic identities in designed Instagram images (Manovich 2020). It provides an own worldview and visual language (e.g. frame, composition, space, themes, photo sequence). An emergent activist tactic that relies on Instagram’s logic is slideshow activism (Dumitrica and Hockin-Boyers 2022). That is a series of slides (images) with short words and graphic components that highlight a particular topic and provide new ways to discuss and translate complex political issues into comprehensible and easily disseminated images. Instagram is thus for humanitarian organizations a tool for modern artivism, or a fusion of art and activism (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018).

The popularity and importance of Instagram are also largely related to the ‘aesthetic society’ we live in, where aesthetically refined consumer goods, services, and experiences are central to economic and social functioning (Manovich 2020). Sophisticated aesthetics are the central characteristic of goods and services, and aesthetically oriented professionals and individuals are valued. Similarly, we live in an increasingly ‘visual age’ (Bleiker 2018). The production and distribution of images have been democratized and they have unprecedented, potentially global circulation and reach. Visual media have become the main semiotic channels for shaping, depicting, interpreting and comprehending the world, including global political topics such as forced migration (Bleiker 2018; Woods and Shee 2021). Visual representations can have powerful political and emotional effects, including through their illusion of authenticity, aesthetic choices, politics of visibility and invisibility and domination and resistance, and their need for interpretation: ‘they delineate what we, as collectives, see and what we don’t and thus, by extension, how politics is perceived, sensed, framed, articulated, carried out, and legitimized’ (Bleiker 2018: 4). Images have fundamentally altered citizens’ lives and interactions. They often evoke and generate emotions, shaping how audiences worldwide perceive, understand, and respond to particular events, including humanitarian crises (Bleiker 2018). By depicting individuals and personal stories, they provide viewers with identification opportunities and make distant, complex political topics accessible. Through close-up portraits of victims, compassion can be evoked in viewers, whereas group pictures rather create emotional distance. However, this process can be affected by compassion fatigue (Moeller 1999), states of denial (Cohen 2001), media fatigue (Campbell 2014), or other societal factors, requiring humanitarian organizations to use considerate social media strategies.

Social media strategies by humanitarian organizations

Rodriguez (2016) found that some asylum-specific NGOs use Facebook and Twitter to share the individualized experiences of forcibly displaced people to elicit compassion and sympathy, reflecting deliberate positivity. Nevertheless, these organizations primarily use social media to disseminate foreign and human rights policy information, which can be considered an attempt to educate the public about systemic change. Carrasco-Polaino et al. (2018) identified two predominant communication strategies among international NGOs on Instagram. Some nonprofits used empowering images of potential project participants, mirroring deliberate positivity. However, to raise awareness about the need for assistance, NGOs portray potential solemn- or concerned-looking project participants (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018), indicating shock effect appeals. Although social media provides opportunities to highlight societal complexities and are often assumed to foster post-humanitarian imageries (supra), mostly the dominant humanitarian representation strategies thus (re)appear.

Although valuable, these studies analyse NGOs’ Facebook and Twitter communication or examine the use of Instagram by NGOs in general. To our knowledge, the Instagram communication strategies of refugee organizations are largely unexplored but can significantly influence public opinions (Chouliaraki 2012b). Having connected commonly separated communication strategies and production, reception and societal contexts, we now extend and refine the literature by comparatively analysing UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies for two crises.

Methodology

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) investigates the influence of discursive features of power dynamics and inequalities (Fairclough 2013). By analysing word and grammar choices, CDA examines the discursive construction and meaning-making of reality (Hansen and Machin 2019; Machin and Mayr 2023). However, as images can also reflect ideologies and power (Machin and Mayr 2023), there has been a growing interest in visual methods. MCDA has therefore been used to critically analyse discourses within both textual and (audio)visual genres (e.g. videos, images). This study analyses discursive strategies in both Instagram images and captions and their interplays, which are central to Instagram’s vernacular and logic (supra). Therefore, we applied MCDA as it scrutinizes how visual and textual elements interact and co-create meaning (Hansen and Machin 2019; Machin and Mayr 2023). Supported by Office software, we applied a comparative-synchronous approach (Carvalho 2008) to consider crisis-related differences.

We examined UNHCR, as it is the key international refugee organization (Clark-Kazak 2009), currently counts 1.9 million followers on Instagram (UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency n.d.), and is extensively engaged in and communicates about the large-scale Ukrainian and Syrian crises. We analysed UNHCR’s Instagram posts as we live in an increasingly aesthetic and visual society (supra) and social media plays crucial roles in influencing the discourses about forcibly displaced people. Their Instagram representations particularly need further investigation (Rosa and Soto-Vásquez 2022). Further, we selected the Syrian and Ukrainian crises for various reasons. First, international refugee organizations face acute dilemmas regarding how to communicate the above-mentioned double standards on refugee protection and tensions with humanitarian priorities and principles (supra). This raises the question of whether and how UNHCR employs different communication strategies for both crises. This is especially relevant given that humanitarian representations of forcibly displaced people from the Global North, including Ukraine, have barely been explored. Second, both crises are internationally important, large-scale, and protracted but were in a different phase in 2022. The Russian-Ukrainian war began in 2014 and settled in 2015 into a violent but static conflict. However, the Russian invasion in 2022 created the fastest displacement crisis since the Second World War (UNHCR 2023). Since then, the Ukrainian crisis has dominated public, media, and political agendas and discussions (Newman et al. 2023). The Syrian conflict, however, started in 2011 and became in 2013 the largest displacement crisis worldwide. However, it has declined sharply and disappeared from media attention in recent years, even though there is a massive, growing humanitarian crisis due to ongoing war, economic collapse, and climate change (The New Humanitarian 2024). The Syrian crisis remains the largest with 13.8 forcibly displaced people at the end of 2022 (UNHCR 2023). We thus fully acknowledge the potential influence of the different and complementary nature of both crises (e.g. crisis phase, scale, context, implications, mediatization) on UNHCR’s communication content. By focusing on the same organization, platform, and year, this comparative approach potentially allows us to investigate whether and how these crisis-specific societal factors influence humanitarian communication, which has hardly been explored.

Further, we analysed the key year 2022, for theoretical, practical, and pragmatic reasons. First, we decided to start our research period on 1 February 2022. As the Russian invasion started on 24 February 2022, the selected research period allows us to analyse UNHCR’s Instagram posts for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises both before and during this escalation of the protracted Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Second, a preliminary examination of UNHCR’s Instagram posts revealed a huge amount of data. Considering the time-consuming nature of our in-depth, comparative, multimodal approach and to ensure a feasible and uniform analysis, equal amounts of data were collected for both the Syrian (N = 45) and Ukrainian crises (N = 45), resulting in a total of 90 analysed posts. Only posts which explicitly refer, textually and/or visually, to these crises were selected. Although the data set is relatively limited and we thus will be cautious in making generalizations, it constitutes a reasonable record of UNHCR’s Instagram posts on both crises, including various topics, times, and places. Considering UNHCR’s different amount of Instagram posts for both crises in 2022, the sample includes material published online between 1 February 2022 and respectively 8 April 2022 (Ukraine) and 1 March 2023 (Syria). As the research periods do not fully coincide, we are cautious in making contextual comparisons and consider the influence of different contexts on the results. However, we do not think this substantially affected the main results. The subsamples of the Instagram posts about the Ukrainian and Syrian crises constitute relatively temporally proximate, limited, and logical entities, which also enable us to make relevant statements about contextual dimensions.

The CDA model of Fairclough (2013), used here, addresses three dimensions: text (i.e. linguistic and visual features of a media text); discursive practices (i.e. production, distribution, and consumption of a media text); and social practice (i.e. broader societal context of the text and discursive practices). (M)CDA is, however, a critical, interpretative state of mind, rather than an explicit, systematic, reproducible research method (Reisigl and Wodak 2016). Hence, to increase the study’s reliability, we reflexively discuss our research decisions and used various discursive criteria, informed by multiple key works (Hansen and Machin 2019; Machin and Mayr 2023) and the literature review. The discursive criteria mainly address the textual and/or visual representation of social actors, such as personalization, impersonalization, individualization, collectivization, specification, genericization, nomination, functionalization, pronouns, distance, and angle. Nevertheless, given the limited and fragmented research on the subject, this study approaches the data also from an open, explorative, inductive perspective. We respond to common criticisms that (M)CDA lacks comparative analyses, spends little attention on (non-journalistic) social actors’ discursive strategies, and is too text-focused, neglecting (audio)visual content (Carvalho 2008; Hansen and Machin 2019). While not distinguishing between Fairclough’s (2013) dimensions of text, discursive practices, and social practices, the latter two are integrated into the discussion of textual strategies to contextualize the analysis. We structure the results according to Scott’s (2014) typology and contextualize them via textual and audience research on humanitarian discourses.

Results

Shock effect appeals: victimized masses and ideal victims

The study shows that UNHCR primarily uses shock effect appeals. It represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians and, to lesser extents, Syrians as victimized, voiceless masses, and highlights ideal victims.

Our analysis revealed that UNHCR mostly textually represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians and Syrians as anonymous masses in need of assistance through shock effect appeals in its Instagram posts, corresponding with previous research (Ongenaert and Joye 2019; Bellander 2022). First, UNHCR often impersonalizes and silences them by not mentioning any personal information (e.g. perspectives, experiences, feelings), which dehumanizes and makes the presented people voiceless (Machin and Mayr 2023). Relatedly, UNHCR often generically presents forcibly displaced Ukrainians (e.g. ‘people in need’, ‘people fleeing’) and, to a lesser extent, Syrians (e.g. ‘a Syrian refugee’, ‘Syrian girls’), which can homogenize their personal experiences and feelings (Machin and Mayr 2023; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). UNHCR frequently reduces their identities to nationality and/or gender and simplifies their sociopolitical and economic contexts. Relatedly, UNHCR often represents them as collectives (e.g. ‘Syrian refugee children’, ‘3 million refugees’), devoid of any individuality, which can also have dehumanizing effects (Machin and Mayr 2023; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). These findings confirm previous criticisms of shock effect appeals denying the dignity of affected people (Scott 2014).

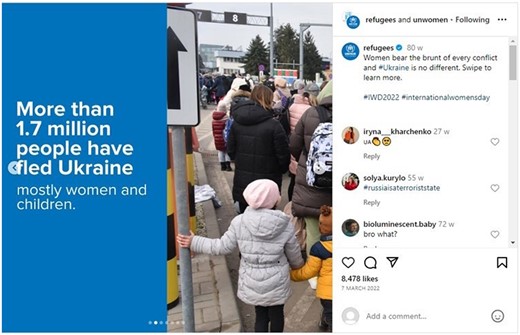

In images, the distance and angles through which people are displayed connote varying relations with the audience, which can affect audience engagement and relatedness (Hansen and Machin 2019; Machin and Mayr 2023). We found that UNHCR often portrayed forcibly displaced Ukrainians and Syrians through eye-level views, which often imply equality, ordinariness, and closeness and facilitate sympathy (Figures 1, 5, and 8) (Machin and Mayr 2023). UNHCR also occasionally uses bird’s-eye views, which usually connote low(er) statuses, physically weak(er) positions, limited agency and/or empowerment (Figures 2 and 3). This reinforces the textual victim narratives and can potentially arouse feelings of pity (Clark-Kazak 2009; Ongenaert and Joye 2019). Moreover, UNHCR often uses medium shots (Figures 1, 2, and 5), which frequently imply intimacy, closeness, approachability, and/or genuineness. Such imagery can facilitate empathy (Machin and Mayr 2023). In sum, UNHCR often seeks to visually reinforce the victim narratives, which can evoke emotions of pity and guilt.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 15 April 2022. © UNHCR/Lilly Carlisle.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 9 March 2022. © UNHCR/Zsolt Balla.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 7 March 2022. © UNHCR/Chris Melzer.

Our analysis shows that UNHCR visually mainly represents helpless and anonymous Ukrainian and Syrian women and children (Figures 1 and 2), corresponding with previous findings on ideal victims (Höijer 2004; Jhoti and Allen 2024). Hence, UNHCR can potentially more easily generate strong emotions of pity and guilt and subsequently awareness and donations (Höijer 2004; Scott 2014). Contrasting with Syrian women and children (infra), UNHCR often portrays forcibly displaced Ukrainians in relatively generic groups, which may diminish their individuality (Machin and Mayr 2023). Nevertheless, UNHCR mostly foregrounds women and children in these groups (Figure 3), which might elicit sentiments of pity (Höijer 2004). Importantly, reflecting UNHCR’s communication focus, most Ukrainian refugees are women and children (UNHCR 2023). Although there are also many (less visible) internally displaced Ukrainians, this probably partially explains UNHCR’s visual sociodemographic focus. The Syrian crisis, however, also involves many children but a more balanced gender division of refugees (ibid.). This indicates the potentially deliberate nature of UNHCR’s focus on ideal Syrian victims (i.e. helpless women and children).

Extending previous research, we found that UNHCR frequently represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians as ‘families’ (Figures 2 and 3). This can create more nuanced, humanized portrayals (Machin and Mayr 2023), and might also mobilize support. As ‘families’ are often associated with affection, warmth, or safety—and thus can also be considered as ideal victims, it may facilitate relatedness and compassion. However, forcibly displaced Syrians are labelled more generically as ‘refugee families’. Due to the constant functionalizing reference to legal status, this term may sound less identifiable and humanizing than ‘families’ (ibid.). By overly highlighting specific sociodemographic groups (i.e. women, children, families) or using different terminologies, UNHCR might indirectly contribute to hierarchies of deservingness within and between population groups. This might influence public perceptions and policy measures and emphasizes the need to develop (more) diverse, balanced, and inclusive representations (Ongenaert et al. 2023b).

Overall, shock effect appeals can be effective in raising awareness and donations (Scott 2014). However, UNHCR’s repeated use of these strategies could in the long term potentially generate compassion fatigue (Moeller 1999; Chouliaraki 2010). Furthermore, none of UNHCR’s Instagram posts address the underlying economic and political contexts of the crises, nor provide recommendations for structural change, confirming earlier criticisms of shock effect appeals and social media posts oversimplifying complex situations (Scott 2014; Ongenaert and Joye forthcoming). UNHCR’s Instagram posts only limitedly contribute to a more comprehensive public understanding of these international conflicts and affected people’s complex experiences.

Deliberate positivity: empowered and talented individuals

The analysis shows that UNHCR also frequently uses deliberate positivity by portraying forcibly displaced Syrians and, to far lesser extents, Ukrainians as ‘heroes’; as talented, empowered, resilient, and unique individuals, likely to engage audiences (Ongenaert et al. 2023b). First, we found that UNHCR substantially individualizes, nominates, personalizes, and specifies them as individuals with unique identities and often resilient experiences by including their names, stories and/or Instagram tags in the captions (Figures 4 and 5). Instagram’s affordances thus allow us to further explore forcibly displaced people’s experiences, stories, and perspectives. UNHCR also often visually individualizes forcibly displaced Syrians, as the agents of stories and emotions (Machin and Mayr 2023). It mainly uses medium shots, often to showcase their activities and cheerful faces and likely to create intimacy, closeness, approachability, genuineness, and empathy (Figure 5, Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018; Machin and Mayr 2023). UNHCR mostly portrayed forcibly displaced Syrians through eye-level views, which often imply equality, ordinariness and/or closeness and can facilitate sympathy and audience engagement (Figure 5). It sometimes uses frog’s-eye views, which often portray the represented people as empowered individuals (Machin and Mayr 2023), corresponding with deliberate positivity (Rodriguez 2016). These representations can be interpreted as more humanized but not necessarily more nuanced (Scott 2014).

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 18 November 2022. © UNHCR/Lam Duc Hien.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 18 November 2022. © UNHCR/Jack Nolos.

UNHCR often functionalizes forcibly displaced Syrians by representing them based on what they do, which can confer legitimacy and authority (Machin and Mayr 2023). However, UNHCR frequently reduces them to their legal status (e.g. ‘refugee’), which can have dehumanizing effects. UNHCR often also mentions highly socially valued functions (e.g. ‘UNHCR Goodwill ambassador’, ‘Olympian’, ‘author’, ‘engineer’), which portrays individuals as respectable, ‘good’ members of society (ibid.). UNHCR thus mainly highlights talented, empowered and/or unique forcibly displaced Syrians (Ongenaert et al. 2023b). These discursive transitions from ‘refugees’ to talented, active citizens illustrate positive changes in their lives. UNHCR arguably aims to highlight their empowerment, agency, talents, and resilience and the positive impact of donor-funded humanitarian assistance (Scott 2014). Likewise, the analysis revealed that UNHCR sometimes combines different distance perspectives within the same post. Forcibly displaced Syrians are sometimes depicted walking in rural areas from long shots to working in professional environments from medium shots (Figures 4 and 5). Hence, UNHCR arguably visually showcases the favourable long-term changes in forcibly displaced Syrians’ lives, reinforcing textual discourses. While UNHCR should of course highlight forcibly displaced people’s development, empowerment, and achievements, it should not neglect, nor deprive the dignity of people without highly socially valued functions or characteristics.

Overall, by portraying individuals in empowered and resilient ways, UNHCR might aim to prove the impact of donations (Scott 2014) and ultimately foment humanitarian engagement (Chouliaraki 2010). Nevertheless, donations from the Global North are often presented as the only way to facilitate social change in the Global South (infra). Deliberate positivity consequently reinforces existing North-South symmetries, including by implicitly fostering the notions of the grateful recipient and the benevolent donor (Scott 2014). Therefore, UNHCR should work to change this dependency narrative, for instance, by educating its audiences on advocacy for long-term, structural policy changes. Moreover, the repetitive illustration of positive change has been criticized for promoting similar inaction outcomes as in shock effect appeals (Scott 2014). Deliberate positivity might convey that humanitarian engagement is no longer necessary (Chouliaraki 2010).

In sum, we found that UNHCR represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians more as anonymous, victimized groups (shock effect appeals), while forcibly displaced Syrians rather as empowered individuals (deliberate positivity). This can likely be partially explained by the phase of the crisis, the geographical location of the represented people, and UNHCR’s related objectives. The Ukrainian crisis grew strongly during the research period, with many people fleeing to neighbouring countries. UNHCR therefore likely portrayed large, victimized groups on the move to emphasize the size and urgency of the crisis (Ongenaert et al. 2023b). The Syrian crisis, however, has been going on since 2011 and many forcibly displaced Syrians have integrated into the region and Europe. UNHCR therefore likely aims to emphasize ‘success stories’ to improve public perceptions in host countries. However, at the same time, Syria has a very difficult security, humanitarian, and economic situation (supra). Nevertheless, UNHCR only occasionally depicts internally displaced Syrians. Previous production research showed that refugee organizations communicate little about and from Syria due to difficult political and security situations (Ongenaert et al. 2023a). This likely explains why UNHCR portrays Syrians more as empowered individuals than as victimized groups, especially as various studies focusing on the ‘peak years’ of the Syrian crisis found opposite results (Ongenaert and Joye 2019; Ongenaert et al. 2023b).

Post-humanitarian appeals: branding, self-centred solidarity, and celebrity humanitarianism

We found that UNHCR frequently combines shock effect appeals and, to a lesser extent, deliberate positivity with post-humanitarian appeals, which are facilitated by Instagram affordances and reflect the marketization of the humanitarian industry (Chouliaraki 2012a; Scott 2014; Bellander 2022). Whereas shock effect appeals are often paired with post-humanitarian branding strategies and self-centred solidarity discourses, deliberate positivity is sometimes connected with celebrity humanitarianism.

The analysis shows that UNHCR constructs its brand, generates visibility, and positively highlights its partners through various branding strategies. First, UNHCR accentuates governmental and own actions and achievements in assisting forcibly displaced people. For instance: ‘We are grateful to the Moldovan officials and people who are helping these refugees’ (Figure 6) and ‘We’re working around the clock to help those in need’ (UNHCR 22 February 2023). Likewise, UNHCR’s images of the Ukrainian crisis sometimes include visual elements related to assisting states, including flags (Figure 6), amenities, or donations, to emphasize their humanitarian involvement. Similarly, UNHCR’s images of the Syrian crisis often include its officials and/or logo, as a separate symbol and/or on relief items and clothing (Figure 7), to highlight its humanitarian assistance. UNHCR thus often prioritizes post-humanitarian self-focused discourses rather than enhancing forcibly displaced people’s voices and agency (Scott 2014). It builds its brand and anticipates common criticisms of limited accountability and transparency in the humanitarian sector (Vestergaard 2008).

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 5 March 2022. © UNHCR/Marin Bogonovschi.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 16 March 2022. © UNHCR/Emrah Gürel.

UNHCR frequently prioritizes consumer interests and values through self-centred solidarity discourses over the urgency of the humanitarian cause (Vestergaard 2008). UNHCR occasionally directly addresses its audience through pronouns like ‘you’ to evoke reflexivity and emotion (Ongenaert and Joye 2019; Ongenaert et al. 2023b): ‘What would you take if you had to flee war?’ (UNHCR 19 March 2022). Likewise, UNHCR often calls for donations or other assistance via references like ‘Please donate via the link in bio’ and ‘You can help us help those in need of urgent support’ (UNHCR 25 March 2022). While UNHCR likely aims to foster audience engagement, this arguably also confirms the criticisms of post-humanitarian appeals fostering limited, emotion- and self-centred notions of solidarity to engage with humanitarian causes (Vestergaard 2008; Chouliaraki 2010). It could promote more altruistic, political, and human-rights-oriented notions of solidarity.

UNHCR uses sometimes the arguably European-centred concept of ‘neighbours’ to emphasize Ukrainians’ geographical proximity and relatedness with European audiences: ‘People across Poland (…) offer a warm welcome to their neighbours’ (UNHCR 1 March 2022). UNHCR frequently applies long shots to strategically showcase forcibly displaced Ukrainians on the move or waiting at the border of neighbouring countries as collective, generic groups of ‘neighbours’ (Figures 3 and 6). However, if repeatedly used, UNHCR might inadvertently promote hierarchies of deservingness and exclude more geographically distant forcibly displaced people, like Syrians.

UNHCR frequently presents optimistic, empowered stories and images of forcibly displaced Syrians involving positive roles of celebrities (e.g. a meeting with Tom Cruise, a selfie with Angela Merkel, Figure 8) (Ongenaert et al. 2023b). UNHCR usually depicts the represented celebrity and forcibly displaced person through eye-level views, which often imply equality, ordinariness, and closeness, and likely facilitate sympathy (Machin and Mayr 2023). Similarly, it mainly uses close-ups, which usually imply intimacy, closeness, approachability, and/or genuineness, and can facilitate empathy (ibid.). However, UNHCR might risk shifting the focus to the celebrity (Chouliaraki 2012b), placing the represented forcibly displaced person’s story and feelings in the background.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 9 July 2022. © UNHCR.

UNHCR might engage in this form of celebrity humanitarianism for various reasons. First, UNHCR may use celebrities’ exposure to highlight urgent humanitarian issues and solutions. While this strategy may generate greater public awareness of crises and engage niche audiences because of the relationship with the celebrity, it may involve a more superficial involvement, rather than deriving from altruistic concerns for the affected people’s well-being (Chouliaraki 2012b). Similarly, UNHCR may use this celebrity visibility to enhance and legitimize its brand, including by highlighting the humanitarian-celebrity encounters and partnerships. This celebrity humanitarianism further highlights the marketized environment in which refugee organizations navigate (Scott 2014).

The analysis revealed that UNHCR’s Instagram communication often relies on Instagram’s affordances, which facilitate the use of post-humanitarianism appeals. First, the agency-lacking representations of forcibly displaced Syrians and, to a lesser extent, Ukrainians, are often portrayed through slideshow activism (Dumitrica and Hockin-Boyers 2022). To highlight their main struggles, UNHCR uses a carousel format consisting of several easily readable and shareable slides with brief texts and graphic features (Figures 3 and 7). However, none of these posts discuss the underlying causes of forced displacement. UNHCR simplifies the complex environments of forcibly displaced people, likely to foster audience engagement. Its reliance on Instagram features, including slideshows, confirms earlier criticisms of post-humanitarian appeals for adequately educating the public (Scott 2014).

Furthermore, UNHCR’s slideshows are always aesthetically colour-coordinated and visually appealing (Figures 3 and 7). This deliberate design strategy could be related to the influence of social media logics, as aesthetics are important on Instagram (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018). Hence, UNHCR’s representations of forcibly displaced people as voiceless victims combined with its prioritization of audience values and ideals further signals the corporatization of the humanitarian sector. By favouring appealing aesthetic practices rather than creating more nuanced, dignified representations, UNHCR participates in consumer-oriented marketing practices. It might risk supporting existing values rather than promoting social change (Vestergaard 2008).

UNHCR creates these aesthetically pleasing posts by using Instagram’s photographic editing tools (Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018), which ultimately alters everyday life representations (Woods and Shee 2021). This practice aligns with the post-humanitarian principles of using attractive and innovative textual and visual strategies (Chouliaraki 2012a; Scott 2014). Moreover, Instagram allows the implementation of easy options to donate (e.g. ‘link in bio’, Figure 6), further facilitating post-humanitarian appeals (Scott 2014). Although it might raise engagement rates (Rosa and Soto-Vásquez 2022), this communication might facilitate rather short-term, trivial engagements in humanitarian causes (Scott 2014).

Discussion and conclusion

This study investigated which main Instagram communication strategies UNHCR uses for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises. We generally observe a mixed picture. The analysis shows interacting humanitarian and post-humanitarian appeals, involving explicit and implicit inter- and intra-group hierarchies of deservingness and crisis-specific differences and commonalities, extending and nuancing earlier research.

First, the study shows that UNHCR mainly uses shock effect appeals on Instagram, likely to evoke pity and guilt (Ongenaert and Joye 2019; Bellander 2022; Ongenaert et al. 2023b). It mainly represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians and, to lesser extents, Syrians, as victimized, voiceless masses, which can have dehumanizing effects. Likewise, it focuses in both population groups on ideal victims (Höijer 2004), including families, which can create hierarchies of deservingness within these groups. Contrastingly, the results indicate that UNHCR mainly portrays forcibly displaced Syrians and, to far lesser extents, Ukrainians, as talented, empowered, unique individuals, presumably to facilitate audience engagement and relatedness (Rodriguez 2016; Bellander 2022; Ongenaert et al. 2023a). UNHCR highlights success stories and quotes of forcibly displaced Syrians, enhancing their agency and voice. UNHCR likely aims to demonstrate the empowering abilities of donor-funded humanitarian assistance. However, by mainly highlighting people with highly valued functions, it creates hierarchies of deservingness (Scott 2014; Ongenaert et al. 2023b).

Extending previous literature, our analysis thus shows important differences in representations between and within the population groups of forcibly displaced Ukrainians and Syrians. This can most likely be partially explained by context-specific differences, including the phase of the crisis, the represented people’s geographical location, and UNHCR’s related objectives. The Ukrainian crisis increased heavily in 2022, with many people fleeing to neighbouring countries. This likely partially explains UNHCR’s large use of shock effect appeals. These appeals likely partially reflect ongoing societal trends but are also often the most effective in generating awareness and financial support, especially for humanitarian emergencies (Scott 2014). The Syrian crisis, however, has decreased in intensity in recent years and many forcibly displaced Syrians have integrated into the region and Europe. This likely explains UNHCR’s use of deliberative positivity, as it aims to generate audience engagement and sympathy to improve public perceptions in host countries and to encourage and demonstrate the relevance of (further) donating (Ongenaert et al. 2023a). In that regard, this study identifies and emphasizes the importance of considering the (potential) influence of crisis-specific societal factors on (humanitarian) communication output and (potential) differences, particularly in critical, comparative media studies. Contextualized, comparative approaches can yield more in-depth, nuanced, multi-layered findings and provide a theoretical basis for further in-depth production research on explanatory production and societal contexts.

Further, UNHCR’s representations partially contrast common Global Northern policy and news narratives, which often differentiate these population groups in explicit, discriminatory ways as respectively ‘heroes’ and ‘victims’, and ‘threats’ and ‘victims’ (Moallin et al. 2023; Zawadzka-Paluektau 2023). UNHCR, however, differentiates these (and other) population groups in more implicit ways, which can also influence public perceptions and policies and affect population groups. UNHCR should thus adopt communication approaches that provide more context and background information on the crises and represent the affected populations sociodemographically in more balanced ways (i.e. going more beyond ideal victims).

Equally contributing to the literature, we found that UNHCR frequently combines shock effect appeals and, to a lesser extent, deliberate positivity with post-humanitarian appeals (Chouliaraki 2012a; Bellander 2022). UNHCR often combines shock effect appeals with humanitarian branding strategies, likely for branding, visibility, and partner reasons, and self-centred solidarity discourses for audience engagement reasons. However, forcibly displaced people’s voices and agency are thereby often neglected. Further, it pairs deliberate positivity sometimes with celebrity humanitarianism, presumably for visibility, legitimization and branding reasons but risks relegating forcibly displaced Syrians to secondary positions (Chouliaraki 2012b). These combinations of humanitarian and post-humanitarian appeals are facilitated by Instagram affordances, including photo sharing and editing tools, which enable aesthetic slideshow activism (Dumitrica and Hockin-Boyers 2022), reflecting the marketization of the humanitarian industry (Scott 2014).

More generally, this study’s findings illustrate how, although social media is often seen as opportunities for more nuanced, comprehensive, and contextualized humanitarian representations (Scott 2014), UNHCR continues to heavily rely on criticized humanitarian and, to lesser extents, post-humanitarian communication strategies for various reasons. Considering its challenging sociopolitical and economic contexts, UNHCR likely participates in humanitarian branding strategies that promote and legitimize its work (Vestergaard 2008). Furthermore, UNHCR largely follows the social media logic of Instagram, which prioritizes the interests and values of Instagram users rather than those of those represented. These Instagram posts are guided by consumerist values and aesthetic ideals, limiting opportunities for contextualized, nuanced representations. Nevertheless, these portrayals can influence public perceptions and behaviours towards forced migration (Ongenaert 2019).

Overall, this study contributes to the literature on humanitarian communication by providing in-depth, comparative, and new insights into the largely unexplored social media communication of refugee organizations for both Global Southern and barely examined Global Northern crises. This study thus provides comparative crisis-specific and platform-specific insights and potential underlying causes and demonstrates that mainly humanitarian imageries, frequently in interaction with post-humanitarian imageries, are used on Instagram, which nuances the often-assumed importance of the latter on social media. Refugee organizations should reevaluate their communication strategies, preferably in dialogue with forcibly displaced people and educate audiences more about the complexities of humanitarian work, communication practices and deeply rooted sociopolitical issues, stimulating public understanding and debate and facilitating new communication practices.

Finally, future research could analyse other semiotic modes, including videos, which are highly predominant on Instagram. Although we both examined media textual, production, and societal dimensions (cf Fairclough 2013), MCDA is largely media text-focused. While we sometimes made substantiated assumptions about the interactions and influences between text, production, societal and/or reception aspects, further empirical research is needed to analyse these. Production research with social media officers of refugee organizations is key in examining underlying influencing motivations and production and societal contexts. Likewise, audience research with relevant audiences (e.g. citizens, forcibly displaced people) is essential to explore their interpretations and responses to this communication. Given the time-consuming nature of our research methodology, we had to focus on one (key) year, one (key) platform, and one (key) actor. We acknowledge the diversity within the working field and cannot generalize organization-specific findings. However, as various international refugee organizations have similar routines and objectives and function in similar institutional and/or societal contexts, we assume that various results largely hold. Nevertheless, further research should analyse large-scale datasets and adopt inter-organizational and/or historical-diachronic perspectives to examine both discursive and contextual evolutions (Carvalho 2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their valuable comments and kind help during the reviewing process, and UNHCR for the permission to publish screenshots of Instagram posts in this article.

Author contributions

David Ongenaert: Conceptualization (lead), Methodology (lead), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Data curation, Visualization, Writing—review and editing, Project administration, Supervision, Resources (supporting), Writing—original draft (equal) and Claudia Soler: Writing—original draft (equal), Resources (lead), Investigation (lead), Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Formal analysis (lead).

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this work.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest and obtained positive advice for this research from their faculty research ethics committee.

Data availability

This study’s analysis documents are, given the involved vulnerable population groups and the theme’s sensitive nature, available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.