-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Faten Kikano, Gabriel Fauveaud, Gonzalo Lizarralde, Policies of Exclusion: The Case of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 34, Issue 1, March 2021, Pages 422–452, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa058

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

When the Syrian war erupted in 2011, the Lebanese government withdrew from managing the influx of Syrian refugees. Three years later, Lebanon’s Council of Ministers set new regulations for Syrians with the purpose of reducing access to territory and persuading refugees to leave the country. This article analyses the reasons for and the outcomes of Lebanon’s response to the refugee crisis before and after 2014. It then examines, through a qualitative exploratory approach and based on two longitudinal case studies, the impact of Lebanese regulations. In both cases, the so-called ‘temporary gatherings’ became permanent settlements beyond the government’s control. The government’s strategy backfired: in attempting to avoid ghettos, it created them. We conclude that when refugee situations become protracted, most efforts aimed at excluding refugees fail. Excluding refugees increases their vulnerability and reduces their chances of repatriation or resettlement. To prevent this, we argue that hosting policies must lead to the temporary integration of refugees within urban systems and public institutions.

The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon

The Syrian conflict began in 2011 and has already led to the displacement of the largest refugee population ever under the mandate of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (UNHCR 2016). Lebanon, a small neighbouring country, now hosts the highest number of refugees per capita in the world (Norwegian Refugee Council and International Rescue Committee 2015; UNHCR et al. 2018). After almost 8 years of ongoing crisis, the Lebanese government, like others in the region, persists in dealing with Syrian refugees as temporary and undesirable settlers. Yet, compared to others, the Lebanese response stands out due to three policies.

First, until 1 January 2015, Lebanon kept its borders with Syria open, allowing large crowds to enter the country in an unplanned and chaotic manner within a short period. Second, and during the same period, The Lebanese government almost completely disengaged from management of the refugee influx. This responsibility was tacitly transferred to municipalities, which adopted dissimilar approaches—ranging from exclusion to hospitality—depending on the socioeconomic and political contexts of the areas they administered. Third, despite the large number of refugees that entered the country, the Lebanese state prohibited organized camps (UNHCR 2017), a decision influenced by the vivid memory of the 70-year presence of Palestinian refugees (Janmyr 2016). Refugees thus settled informally in different types of houses and shelters. They concentrated in areas where municipalities took a lenient and empathic approach, resulting in an unprecedented strain on public, urban, and socioeconomic systems in these areas (Loveless 2013; Thibos 2014).

By the end of 2014, the national government finally engaged with the refugee crisis. It closed official border crossing points with Syria. Simultaneously, the Council of Ministers approved a ‘Policy Paper on Syrian Refugee Displacement’, which was the first official document issued by the Lebanese state since the beginning of the crisis. The paper included a new set of regulations preventing Syrians from entering Lebanese territory and tightened restrictions on residency and work permits (both issuance and renewal) for Syrians already in the country. These regulations aimed to reduce the number of Syrians in Lebanon. Consequently, most Syrians became illegal settlers, living at the risk of arrest and deportation (Frangieh 2015; Lenner and Schmelter 2016). This situation deprived them of a number of rights and privileges, including (1) accessing most public services, (2) legally owning or renting a dwelling, (3) participating in the formal job market, (4) seeking aid and protection from official institutions, and (5) moving freely within the country.

Refugee hosting policies have been the subject of a number of studies since 2011. Some studies focus on how the Lebanese national government’s vulnerability and internal conflicts led it to disengage from any sort of crisis management (Naufal 2012; El Mufti 2014; Dionigi 2016; Mourad 2017). Others concentrate on the discriminatory policies that deprived refugees from obtaining legal status in Lebanon (Frangieh 2015; Saghieh 2015; Janmyr 2016). They typically examine this issue from a legal and social perspective. Several authors have analysed the outcomes of the open-border and non-encampment policies. While some see them as a risk to the country’s stability (Loveless 2013; Onishi 2013; Thibos 2014), others argue that they were intentionally adopted to raise the supply of cheap labour (Fawaz et al. 2014; Turner 2015; Sanyal 2017). These studies generally lack insight into how various hosting policies affected the evolution of temporary refugee spaces, as well as their vulnerability and that of the communities hosting them.

This study seeks to illustrate the impact of policies of exclusion on Syrian refugees’ living conditions in Lebanon. It analyses the influence of such policies on housing conditions, economic conditions, social stability, security, the landscape and built environment, and the impact on and availability of services and infrastructure. It explores specific aspects of the Syrian refugee crisis in which there has been little systematic research by answering the following research question: How do policies of exclusion aimed at preventing refugees’ permanent settlement affect their vulnerability and living spaces?

In this article, we argue that the Lebanese policies of exclusion increase refugees’ vulnerability and structure it for the benefit of local actors. We also argue that institutionalized discrimination against refugees limits their movements and results in their confinement.

We outline four main outcomes resulting from the exclusion of refugees:

Disruption of formal governance structures.

Exacerbation of refugees’ socioeconomic stratification.

Ghettoization of non-camp spaces.

The limited impact of refugees’ type of accommodation on their living conditions.

From a theoretical perspective, our findings reveal new evidence on the evolution of refugee spaces regarding their porosity and appropriation by their inhabitants. They show that regardless of the type of settlement (camp or non-camp), appropriation of refugee spaces is related to refugees’ institutional standing and to their socioeconomic status. From an empirical point of view, our findings reveal the outcomes of national refugee-exclusion policies and highlight the advantages of more inclusive strategies.

In this article, we first examine the specificities of the Lebanese refugee policy. Second, we reveal the benefits and drawbacks of Lebanon’s approaches through two case studies. Third and finally, we discuss our results and conclude with theoretical and empirical implications.

Methods: Longitudinal Case Studies

The research consists in two longitudinal case studies, following the method suggested by Yin (2003). The approach is qualitative exploratory and is grounded on inductive reasoning. The case study method provides an in-depth understanding of contextual elements related to refugees’ living conditions (Creswell 2007). The longitudinal study allows us to assess the refugee situation over 4 years, with the specific intention of evaluating how refugees relate to their spaces. We adopted two complementary methodological approaches: ethnography and narrative analysis. As such, our study involves, through discussions with refugees, analysis of the meanings, representations, and values. Ethnography helps us to understand refugees’ perceptions as part of complex socio-political contexts (Harrell-Bond and Voutira 1992), whereas narrative analysis allowed us to interpret local explanations (Schweitzer and Steel 2008), with a specific reflection on the cultural and political connotation of language.

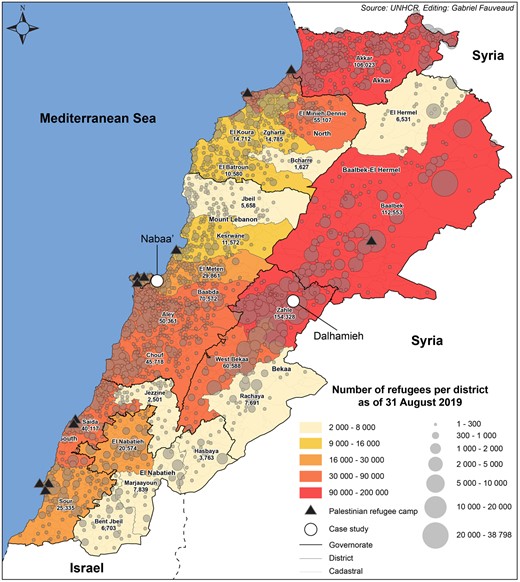

The first case is an informal settlement in Dalhamieh, a small rural village in eastern Lebanon surrounded by vast agricultural lands and located about 20 km from the Syrian border. Almost 800 refugees inhabit 90 tents built on approximately 3000 m2 of land. The village lies within the Zahleh cadastre and is administered by the Zahleh municipal government. The second case study is located in Nabaa, a densely populated neighbourhood of 0.2 km2 accommodating low-income Lebanese and migrant populations. Nabaa is located in the eastern suburbs of Beirut, within the Burj Hammoud cadastre. It falls under the jurisdiction of the Burj Hammoud municipality (Figure 1). Just like the rest of Burj Hammoud, most of Nabaas buildings were constructed from the 1930s to 1950s and have not undergone any meaningful upgrades since then. A survey by UN-Habitat in 2016 found that nearly 15000 people live in Nabaa’, two thirds of whom are Syrian nationals (UN-Habitat 2017).

Distribution of Syrian Refugees in Lebanese Districts

Source:UNHCR (2019).

We chose to study these two locations because of the large number of refugees hosted, and because both areas have excluded refugees from legal and formal systems—although, as we will see, this exclusion is for different reasons and with dissimilar dynamics.

Four main field visits for data collection took place in both areas between 2014 and 2017. Data collection was based on field observation operated on two scales in each area: in Dalhamieh, at the scale of the sheltering units and the settlement, and in Nabaa’, at the scale of the living spaces and the entire neighbourhood. Pictures, sketches, and plans related to the spaces’ physical structure and evolution over time were taken or drawn. This information was complemented by eight discussions held with focus groups of Syrian refugees and Lebanese inhabitants in both areas. Sixteen semi-structured interviews were also carried out with other stakeholders, including ministers representing different religious groups and political parties, heads of municipal councils, locally based academics, and humanitarian-aid workers. Documents, reports, and papers produced by governmental institutions, UN bodies, and other organizations were also reviewed (Table 1).

| Methods . | Case studies . | Source . | Year . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Dalhamieh | Head of the municipal council of Zahleh (1) | 2017 |

| Nabaa | Head of the municipal council of Burj Hammoud (1) | 2017 | |

| Group discussions | Dalhamieh |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

| Nabaa |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 | |

| General interviews |

| 2017 | |

| Study of reports, documents, and grey literature |

| 2014–17 | |

| Field observation | Dalhamieh | Pictures, drawings, and plans | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 (3rd location of the settlement) |

| Nabaa’ | Pictures, drawings, plans, and satellite images (UN-Habitat) | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

| Methods . | Case studies . | Source . | Year . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Dalhamieh | Head of the municipal council of Zahleh (1) | 2017 |

| Nabaa | Head of the municipal council of Burj Hammoud (1) | 2017 | |

| Group discussions | Dalhamieh |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

| Nabaa |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 | |

| General interviews |

| 2017 | |

| Study of reports, documents, and grey literature |

| 2014–17 | |

| Field observation | Dalhamieh | Pictures, drawings, and plans | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 (3rd location of the settlement) |

| Nabaa’ | Pictures, drawings, plans, and satellite images (UN-Habitat) | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

| Methods . | Case studies . | Source . | Year . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Dalhamieh | Head of the municipal council of Zahleh (1) | 2017 |

| Nabaa | Head of the municipal council of Burj Hammoud (1) | 2017 | |

| Group discussions | Dalhamieh |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

| Nabaa |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 | |

| General interviews |

| 2017 | |

| Study of reports, documents, and grey literature |

| 2014–17 | |

| Field observation | Dalhamieh | Pictures, drawings, and plans | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 (3rd location of the settlement) |

| Nabaa’ | Pictures, drawings, plans, and satellite images (UN-Habitat) | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

| Methods . | Case studies . | Source . | Year . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Dalhamieh | Head of the municipal council of Zahleh (1) | 2017 |

| Nabaa | Head of the municipal council of Burj Hammoud (1) | 2017 | |

| Group discussions | Dalhamieh |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

| Nabaa |

| 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 | |

| General interviews |

| 2017 | |

| Study of reports, documents, and grey literature |

| 2014–17 | |

| Field observation | Dalhamieh | Pictures, drawings, and plans | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 (3rd location of the settlement) |

| Nabaa’ | Pictures, drawings, plans, and satellite images (UN-Habitat) | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 |

Our questions generally focused on the impacts of locally implemented policies regarding refugees’ sheltering solutions and their socioeconomic and institutional capital, and on the interactions, tensions, and power struggles between different stakeholders engaged in managing the refugee crisis.

To mitigate bias, we triangulated data from different categories of participants with conflictual interests (Creswell 2007). For that reason, we purposefully chose to compare refugees’ statements to those of local community members, aid workers, researchers, and officials.

Refugees represented the largest group of participants, followed by local community members. With both groups, we favoured focus group discussions because Syrians and Lebanese are culturally keener to communicate as a group. Refugees were adult men or women and heads of households. We did not include Syrian workers established in Lebanon before 2011, or newcomers who would lack perspective on the topics explored.

In Nabaa’, it was hard to keep track of the same refugees each year because they suffered continuous evictions. However, despite the inconvenience of collecting data from different participants, the information they communicated was relatively constant, which validated our approach. In Dalhamieh, conversely, we were able to hold group discussions with most of the same participants year after year, because those informal settlements hosted the same refugees.

Interviews with different government officials, including municipal leaders, elucidated the reasons for national and local hosting policies. Given the country’s political divisions and fragmented decision-making processes, each municipality adopted unique policies. These were often linked to the political allegiance of the head of the municipal council, and to the local socioeconomic and cultural context.

The main researcher, a Lebanese national of Syrian and Lebanese origin, conducted the fieldwork. Her familiarity with the Syrian culture was an asset that allowed her to choose the best approaches for data collection. Her knowledge of the Syrian dialect facilitated communication with refugees without the need for a translator.

When the study began, Syrians, hospitable by culture, welcomed the main researcher and were not afraid to be open in communicating information. However, the situation gradually changed over the years as intercommunal tensions deepened. The researcher invited a Syrian national, long employed in a family business, to accompany her to help put interviewees at ease.

The Lebanese Policy up to 2014: ‘The Policy of No Policy?’

The Refugee Influx and the Open-Border Policy

In 2019, Lebanon was host to almost 1.5 million Syrian refugees, along with 31502 Palestinian refugees from Syria, 35000 Lebanese returnees, and a pre-existing population of more than 277985 Palestinian refugees—making it the nation with the largest refugee population per capita. This situation has placed unprecedented strain on the country’s already substandard infrastructure, public services, and economy (Loveless 2013). According to the United Nations, Lebanon is considered to be ‘at the forefront of one of the worst humanitarian crises of our time’ (Government of Lebanon & The United Nations 2017).

While the refugee influx suggests that the borders were left open specifically to allow Syrians fleeing the conflict to enter Lebanon, the reality is that borders between the two countries have essentially been porous for decades. In fact, a longstanding agreement between Lebanon and Syria asserted that both states ‘shall endeavour, each in its country, to ensure the freedom to stay and of movement for the other Party’s citizens within the framework of the laws and regulations in force’ (Syrian Lebanese Higher Council 1991). Hence, crossing the border into Lebanon was very easy for Syrian nationals. With a passport stamp, applied free of charge by officers at the border, they could remain in Lebanon for 6 months. Those who wished to stay longer could obtain a 1-year residency permit for US$200. This explains why an estimated 300000–600000 Syrian workers were already living and working in Lebanon before the start of the Syrian crisis (Chalcraft 2007).

But the Lebanese position towards letting in hundreds of thousands of Syrians cannot be analysed solely according to the agreement signed by both states, and ought to be examined separately. Political analysts and scholars propose three different readings of Lebanon’s open-border policy. First, many authors describe the Lebanese response as a ‘policy with no policy’ (El Mufti 2014), or the ‘ostrich policy’ (referring to the popular, although mythical, idea that ostriches bury their heads in the sand when threatened) (Saghieh and Frangieh 2014), and consider it an oblivious response to the influx of Syrian refugees. They relate it to the political instability that the Lebanese state was then undergoing (Yassin et al. 2015). In fact, at the time (2011–13), following the Hariri government’s fall in 2011, the country was being run by a controversial interim government led by Prime Minister Miqati (Dionigi 2016). Bringing the discussion of Syrian refugees to the table would have jeopardized the country’s precarious stability (Naufal 2012). Second, given that a large majority of Syrian refugees are Sunnis, a number of political actors we interviewed consider the open-border policy a strategy led by Sunni political leaders in Lebanon in hopes of increasing the country’s Sunni population. According to a municipal representative, ‘the [Syrian] Sunni presence is meant to counterbalance the weapons of the Hezbollah’, a Shiite political party. Finally, pro-Syrian-regime Lebanese politicians believed the dictatorial regime of Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian president since 2000, was essentially stable. Thus, they expected that the war would end in a matter of months and that Syrians would quickly return home (El Mufti 2014). Overwhelmed by the refugee crisis and hobbled by a fractured governance system, the Lebanese state disengaged from managing the refugee crisis and transferred all responsibility to municipalities.

Decentralization: The Transfer of Crisis Management to Municipalities

The Lebanese state had neither the capacity nor the will to manage the refugee crisis (Frangieh 2015). As of 2019–2020, several years of civil war (1975–90) and corruption have weakened public services and infrastructure. Despite the government’s efforts to upgrade public systems, they remain substandard and insufficient to meet people’s needs: the power grid falls short of demand and suffers blackouts, water is undersupplied, and roads remain in poor condition and heavily congested (Yassin et al. 2015). Thus, a sudden 30 per cent increase in the population has severely impacted already deficient public systems (World Bank 2013).

The civil war not only weakened the country’s infrastructure, but it also marked divisions between and within different communities. The Syrian conflict deepened those divisions, and Lebanese politicians were split into being either opponents or supporters of the Syrian regime (Dionigi 2016). Yet another consequence of the civil war is Lebanon’s struggle to maintain peace and security against a backdrop of simmering tensions between militarized Sunni Palestinians in camps, the Hezbollah Shia party, and the constant threat of an Israeli assault (Janmyr 2016). Disagreements within the national government worsened when Hezbollah, the Shia Lebanese party, declared its allegiance to the Syrian Assad government and entered military involvement in the war in Syria (Janmyr 2016). Had the Lebanese government engaged with the Syrian refugee situation, it would have amounted to politicizing the crisis and heightening tensions between the country’s ruling parties (Dionigi 2016).

Finally, as we concluded from our interviews with government representatives, it seems that by disengaging from the refugee crisis, the Lebanese state wanted to assert its position to the international community of refusing to become a country of asylum for almost 1.5 million Syrians.

As a result, responsibility for refugee control and administration was transferred to municipalities. Their tasks included providing shelter, power, water, health services, and youth education, as well as maintaining security and stability (Boustani et al. 2016; World Bank 2016). The central government’s disengagement also left municipalities free to adopt a wide variety of regulations in hosting refugees, ranging from exclusion to hospitality. Each municipality adopted a specific approach according to its economic and social context and the political position of the elected municipal council. In most cases, municipalities did not impose restrictions on wealthy Syrians, but instead targeted only poor refugee communities (El Helou 2014).

The Non-Encampment Policy

The Lebanese government was praised by the international community not only for allowing Syrians to enter the country freely but also for prohibiting camps and allowing them to settle freely. However, humanitarian motives and good neighbourly relations were not the sole reasons for this decision, and in Lebanon—as in all countries where refugee settlement policies are influenced by political and economic interests (Kibreab 1999; McConnachie 2016)—a number of factors are behind the prohibition of camps for Syrians.

To start, it is worth mentioning that since most Syrian refugees are Sunnis, in Lebanon’s political system, they represent a threat to the fragile power-sharing arrangement organized along sectarian lines, as well as to other religious communities (Henley 2016; Karam 2017). Hence, non-encampment was not unanimously supported amongst politicians: while some saw camps as ‘a solution to a security threat’, others considered them a source of potential ‘security threats’ (Turner 2015: 392). Politicians representing Hezbollah were the fiercest opponents to camps. They feared that camps would become a hideout for Sunni terrorist groups. Conversely, most Christian politicians favoured camps and considered them a tool to control and contain the refugee population (Onishi 2013). Ultimately, fear of a recurrence of the almost 70-year Palestinian camp experience—during which refugee camps became militarized and self-governed neighbourhoods (Doraï 2006; Hanafi and Long 2010)—pushed the government to prohibit camps (Janmyr 2016).

From an economic perspective, non-encampment allowed Syrian refugees to participate in the low-wage labour market, in which they were often indispensable (Turner 2015). Given the difference in value between the Lebanese and Syrian currencies, Syrians accepted lower wages than Lebanese workers. Consequently, sectors like services, agriculture, and construction hired Syrians almost exclusively (Chalcraft 2007; Turner 2015).

Ultimately, refugees found homes in more than 2000 different locations in housing solutions that were often in poor condition (Loveless 2013; Kikano 2015). As of 2014, almost 60 per cent of refugees live in rented rooms or apartments, and 20 per cent live in informal settlements. Many refugees rent non-residential spaces such as shops, offices, and schools. The Lebanese government’s decision to give them the freedom to settle is a double-edged sword, as it brings about a number of challenges. In most cases, arrangements between Syrian refugees and Lebanese property owners are based on illegal rental agreements, which puts the renters at the risk of frequent evictions and exploitative rent prices (Fawaz et al. 2014, Kikano and Lizarralde 2018). Moreover, in most areas with high refugee density, informal housing solutions have led to the uncontrolled emergence of spaces that are significantly altering the landscape, straining services, and negatively impacting the environment (Kikano et al. 2015). However, the extended duration of the Syrian conflict and the large number of hosted refugees eventually instigated a change in the Lebanese position. The next section will focus on these changes.

The Policy of Exclusion after 2014

‘We will deal with them [the Syrian refugees] as we dealt with the Palestinians: by pushing most of them out of the country’, argued one of the ministers we interviewed. In October 2014, almost 3 years after the Syrian war erupted, the central government finally took action. The Council of Ministers adopted a ‘Policy Paper on Syrian Refugee Displacement’, Warakat Syasat Annousouh, including several measures aiming to decrease the number of Syrians in the country by prohibiting Syrian refugees from entering Lebanon, and pressuring those already residing in Lebanon to return to their homeland. The new regulations were implemented by the General Directorate of State Security, the country’s top security agency (Frangieh 2015; Lenner and Schmelter 2016).

It is important to note here that Lebanon did not sign the 1951 Geneva Convention related to the status of refugees (United Nations 1951) and refuses to acknowledge the principle of refugees’ integration. Lebanon hence lacks legislation in its body of laws for dealing with refugees (Frangieh 2015). According to an agreement signed with the UNHCR in 2003, Lebanon is a country of ‘transit’, not one of asylum (UNHCR 2011). However, Lebanon is a signatory of other international conventions and is bound to protect refugees by other principles, not least of which is the principle of non-refoulement (Janmyr 2016), which guarantees, under international human rights law, that no one should be returned to a country where they face inhuman or degrading treatment. This is why, despite refugees’ lack of legal residency documents, those arrested are usually released a few days later with a written warning, either for the regulation of their identification papers or an ultimatum mandating their return to Syria. Syrian refugees were seldom actually deported, and even then only in exceptional cases (e.g. after conviction of a serious crime) (Saghieh and Frangieh 2014).

Thus, new rules were based on Lebanon’s 2014 policy; they included new requirements for Syrians trying to cross the border and for Syrians already in Lebanon applying for and renewing their residency permits (Frangieh 2015). Obtaining or renewing a residency permit requires paying a US$200 fee every 6 months. But families seldom choose to spend their limited funds on renewing legal documents; they have to prioritize basic needs such as food, health care, and shelter (Norwegian Refugee Council and International Rescue Committee 2015). Moreover, the legal procedures became so complex that most Syrians could not follow them. In addition to the fee, the applicant must provide a document signed by the mukhtar (village leader) certifying that he or she lives in an owned or rented property. This document is almost impossible to acquire because most Syrian refugees in Lebanon have informal rent agreements—and even if their occupancy arrangements are legal, municipalities often prevent them from registering their rent agreements.

Syrian refugees are also forced to choose between the right to work and the right to receive aid. Syrians who wish to get a legal work permit lose the right to be registered with the UNHCR and to benefit from humanitarian aid (Lebanon Humanitarian INGO Forum 2015). Consequently, refugees are caught between the hammer and the anvil, between having no access to aid, and gaining legal status yet becoming vulnerable precarious workers. They are also asked to provide a kafala, or ‘pledge of responsibility’ signed by a Lebanese business owner who agrees to sponsor the applicant. Syrians with sponsorship are theoretically eligible to obtain legal residency as well, but the success of each application is at the discretion of the General Security Office, a governmental organization responsible for issuing visas and residency permits for visitors into Lebanese territory. According to a number of interviews, in many cases, even Syrians who provide all the required documents and pay the fees have their applications refused for vague reasons.

Based on the new regulations, Syrians wishing to enter the country must prove that their stay fits into one of the approved entry categories: (1) tourism (proof of hotel reservation, and the possession of US$1000, or proof of real-estate rent or ownership are required); (2) education; (3) in transit to a third country; (4) forcibly displaced individuals ; (5) medical treatment; (6) embassy appointment; or (7) work (requiring the aforementioned pledge of responsibility) (Frangieh 2015). All entry applications must be approved by the Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA) and the Ministry of Interior. Most categories only permitted stays of 24 h to one month, which could only be extended in specific cases (Amnesty International 2015).

These measures were discriminatory, because they excluded other foreigners and targeted only Syrians (Norwegian Refugee Council and International Rescue Committee 2015). Moreover, they targeted poor Syrians in particular (Frangieh 2015). According to Saghieh (2015), the new regulations implied that authorities divided Syrians into three groups: (1) wealthy Syrians with financial resources and the ability to meet new residency requirements; (2) working Syrians with a Lebanese sponsor; and (3) poor Syrians, who remain unregistered and in a precarious legal position. Most fall into this third category (Saghieh 2015). In fact, according to humanitarian organizations, an estimated 80 per cent of Syrians in Lebanon lack legal residency and risk being detained for their unlawful presence in the country (Human Rights Watch 2017). Their legal condition limits their freedom of movement and access to justice and protection (Saghieh 2015). They are deprived of the rights to acquire property, proof-of-identity documents, and formal employment (Janmyr 2016). Moreover, the sponsorship system places control in the hands of Lebanese employers, leaving Syrian workers completely dependent on them (Saghieh 2015).

As for refugees’ housing, the Council of Ministers assigned the MoSA to manage most issues relating to refugees. One of the ministry’s main tasks is to prevent refugee spaces from becoming permanent (Norwegian Refugee Council and International Rescue Committee 2015; Janmyr 2016). This is specifically noticeable in informal settlements, where the ministry’s representatives—referred to by an UNHCR representative we interviewed as ‘the government’s watchdogs’—impose strict conditions on humanitarian agencies regarding shelter-related interventions. Agencies can only perform maintenance works like waterproofing and consolidating shelters, not permanent improvements (Onishi 2013; Kikano 2017). Moreover, refugees are often forced to remain on the same land on which they originally settled, unless the municipality allows them to resettle. Landowners take advantage of this situation by imposing high and exploitative rents. In urban areas, refugees are less visible than in informal settlements, and in many cases, more vulnerable. Their housing conditions (such as rent, physical conditions of the space, levels of crowding, eviction procedures) are at the discretion of local authorities and/or landowners. Refugees often suffer from exploitative rents and unlawful evictions, but their institutional precarity leaves them without any legal recourse (Fawaz et al. 2014).

Since the beginning of the crisis, the Lebanese government had never legally acknowledged the UNHCR registration for refugees. But as of 6 May 2015, it instructed the UNHCR to temporarily suspend new registrations for Syrians, including those already in the country (with the exception of severe humanitarian cases). This has left a large Syrian population unregistered and unable to receive aid (UNHCR 2019). Even the terminology used in official documents supports the exclusion of refugees. For example, while the UNHCR characterizes Syrians in Lebanon as individuals who are likely to meet the definition of ‘refugees’, the Lebanese government refers to them as ‘temporarily displaced individuals’ (nazihoun) and to their settlements as ‘gatherings’ (tajammouat) (Janmyr 2016).

Our in-depth study in Dalhamieh and Nabaa’ has allowed us to understand the effect of the policies adopted on Syrian refugees’ housing conditions in Lebanon, as well as their economic, institutional, and social situation.

The Benefits and Drawbacks of Policies of Exclusion in the Informal Settlement in Dalhamieh

Home in Displacement: Refugees’ Voluntary Invisibility

‘As long as we don't see them, they are none of our concern. Lebanese residents are our sole responsibility’. It is with these words that the head of the municipal council in Zahleh brushed aside the almost 500000 Syrians living in the cadastre, also home to 400000 Lebanese citizens. The municipality, unwilling to manage the crisis, excluded refugees without exerting significant restrictions on them. Instead, it simply ignored their presence. It allowed them to build settlements, provided they remain far from the city. This strategy has led almost two thirds of the Syrians in the area to favour informal settlements in semi-rural areas on the outskirts of the city, rather than apartments and rooms in the city itself. The informal settlement in Dalhamieh is one of several encampments sheltering Syrians in the Zahleh area (Figure 2).

Informal settlements are where the poorest refugees end up, since they represent the cheapest housing solution: each household pays around US$80 per month to rent the parcel of land on which their tented shelter is built. As for the shelters’ building materials, they are partly provided by Non-Governmental Organisations and partly bought or recovered by refugees themselves. To rent a single room in town, the price would be at least three times higher. Many settlements existed before the Syrian war but consisted of a small number of tents occupied by Syrian agriculture workers. More tents were built to host Syrians fleeing the war and small gatherings developed into large settlements, some of which hosting hundreds of people (Kikano et al. 2017).

Refugees in the Dalhamieh settlement are wealthier than refugees in other informal settlements. ‘Our husbands lived and worked in decent conditions in Zahleh before the Syrian war. Many of us are legal residents’, claimed Amina. A few refugees are even Lebanese citizens and enjoy all civil rights. When family members and friends arrived from Syria, they rented a piece of land and built the settlement that shelters them all. Most refugees can afford to rent rooms or apartments in the city, but they have chosen to live in the informal settlement of Dalhamieh. A close examination of their situation elucidates why.

First, the settlement’s location, somewhat remote from peripheral villages, allows refugees a voluntary invisibility that reduces the risk of tension with local residents. ‘They leave us at peace here. They forget about us because they don't see us. We couldn’t have lived like that if we were in rented apartments in the city’, said Farah, our main respondent in Dalhamieh. In fact, with their relatively significant economic capital and large numbers of residents with legal status, refugees’ deliberate isolation increases their power over their settlement. Farah’s assertion also confirms what we concluded from the group discussions held with local community groups about Zahleh’s inhabitants, predominantly Christians, being reluctant to host people of another faith and culture, and perceiving them as both an existential and a security threat. Thus, refugees have a sense of safety and security in the settlement, which has become a haven for them.

Second, almost all refugees are originally from the locality of Idlib in Syria, and they form a homogeneous group. ‘You want to know why there is more order in our settlement and in our shelters [than in other informal settlements]? It’s because of where we come from’, claimed Amina when we enquired about the spatial organization and the sense of order in most of the shelters. In fact, according to refugees’ accounts, living in the settlement allows them to preserve their traditions and to reproduce community life as it was before their displacement. This phenomenon is especially apparent in the recurrence in most shelters of objects with cultural symbolism, such as the colourful and carefully organized mouneh (winter food reserves) that feature prominently on kitchen shelves (Figure 3). It also appears in the contrast between the precarious exterior appearance of the settlement and the well-furnished interior of most shelters, decorated with almost as much care as any typical rural Syrian home (Figure 4). This contrast—recurrent in most informal settlements occupied by Syrians (Kikano 2018)—is a typical pattern in Syrian architecture (Corpus Levant Team 2004).

Mouneh Display (Preserved Seasonal Food), a Pattern Seen in Almost Every Tent in the Settlement

Source:Kikano (2017).

Interior the Tent Owned by a Relative of the Shaweesh (Settlement Leader)

Source:Kikano (2017).

Third, the shelters’ structural flexibility allows refugees to adapt dwellings to suit their aspirations and ways of life. The usual layout assigns the most space to the majlis where, according to traditions of hospitality, guests are hosted. The partitioning of space also allows women’s privacy to be taken into account, so women are able to circulate discreetly in, out, and within the space, avoiding the mainly male-occupied majlis. Refugees design the space according to the number and age of family members. It is possible to implement additional spaces if the number of family members increases following the arrival of relatives or friends from Syria or the birth of a child. These transformations, along with construction works undertaken to upgrade shelters—such as pouring a concrete foundation, and rebuilding wood or even gypsum board partitions—are only possible due to the municipality’s limited control and the remote location. This explains why refugees were able to build a number of stores in the settlement that serve locals and Syrians. Most of these economic activities are undertaken by women, who simultaneously take care of their families and dwellings, whereas most men work in the city, a 20-min drive away. However, the municipality’s lack of involvement also has a number of disadvantages.

Refugees’ Autonomy and Isolation: A Double-Edged Sword Limiting the Protection of the Most Vulnerable

According to the municipal chief officer, the municipality is reluctant to communicate with humanitarian organizations assigned to the area. By avoiding contact, it seeks to express its disengagement from management of the refugee crisis. Consequently, the municipality is generally excluded from funding and decision-making processes. The UNHCR receives, manages, and controls all international funds without consulting with local authorities.

Moreover, according to refugees’ accounts, besides receiving construction material, the financial independence of most residents limits frequent interactions with humanitarian actors. This, along with the municipality’s disengagement, leaves the refugee community with limited oversight and protection. Are vulnerable refugees ever abused by the shaweesh (camp manager) or other influential figures? Are any members of extremist groups hiding in the settlement? Do any other illicit activities take place? These possibilities are almost impossible to confirm or deny due to the settlement’s isolation.

Furthermore, over the years, and due to the escalation of social tensions between Syrians and Lebanese, the Syrian inhabitants’ hospitable attitude has changed. Strangers, even if they are Syrians from other settlements, have become unwelcome, which leads us to construe that the settlement is slowly becoming a concealed and self-governed space.

Refugees’ autonomy has enabled them to develop a strong sense of appropriation of the space. However, their sense of appropriation is only psychological. It has no legal or juridical value and does not give them any rights over the space they occupy. In fact, refugees in Dalhamieh have already been evicted twice from the land they were renting. ‘The first time, the army asked us to leave because our settlement was close to a road the military often used’ said Farah. ‘The second eviction was because the landowner raised the rent and we could not afford to pay it’. Our 2017 data collection took place in the settlement that refugees had built for the third time in a new location.

The Environmental Drawbacks of Unorganized Refugee Settlements

Throughout all of these displacements, the informal settlement in Dalhamieh, like most settlements in the Bekaa Valley, was repeatedly built on agricultural land. The Bekaa Valley accounts for 49 per cent of the total agricultural area in Lebanon. It is the biggest producer and largest exporter of fruit, vegetables, and grains in Lebanon. With most refugees renting plots of arable land for their settlements, agricultural production has dropped. Although building on agricultural land is against the law, renting land (to refugees) is considerably more profitable than using it for agriculture. The municipality is not in a position to enforce a law that would cause landowners to miss out on earning money—and that would cost the municipal council many votes in future elections.

In addition to the reduced agricultural production, the Dalhamieh settlement, similar to most informal settlements in the region, has instigated other environmental drawbacks due to its exclusion from the municipal urban structure. First, the settlement is not connected to the public sewage system, so it contaminates the water table. Second, refugees usually obtain power and water through illegal connections to the official supply, straining local services and infrastructure and disfiguring the environment with anarchically connected wires and pipes. In some cases, settlement residents produce their own electricity through private generators and buy water from water tanks distributed in trucks. These activities are indirect sources of air and noise pollution.

Finally, the proliferation of settlements in the Bekaa valley has caused the region’s land to lose much of its landscape value. Given the MoSA-imposed restrictions on shelter construction materials and their upgrades, as well as the shortage of funds, most Syrian refugee settlements in the Bekaa Valley are an assemblage of incoherent, amorphous, and unpleasantly disorganized structures. The Dalhamieh settlement, despite its occupants’ unusually high financial resources, is no exception. It seems that refugees in the settlement keep its external appearance shabby on purpose, as they do not want it to stand out from other settlements and attract unwanted attention.

The Benefits and Drawbacks of Policies of Exclusion in Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood Nabaa

Authority Absenteeism and the Emergence of Private Forms of Governance

The case of Syrian refugees in Nabaa was ambiguous. It is unclear why refugees have concentrated there specifically, despite harsh and insecure living conditions and the different belief system of local residents (Lebanese real-estate owners in Nabaa are mostly Shiite Muslims, whereas Syrian refugees are Sunni). It was also unclear why Syrians were less inclined to reside in the other parts of Burj Hammoud, given that both areas are managed by the same municipality. The triangulation of data from different respondents was necessary to understand how the peculiar dynamics between stakeholders lead Nabaa to become what local academics refer to today as ‘an urban refugee camp’ (Fawaz et al. 2014).

Unlike in Zahleh, Burj Hammoud’s municipal chief officer got involved in managing the refugee crisis and supports humanitarian and development initiatives in the region. But whereas in other parts of Burj Hammoud the predominantly Armenian population proceeds lawfully in most dealings with Syrians, one of our respondents told us that ‘the Lebanese residents who rent apartments and commercial spaces to Syrians in Nabaa seldom accept any interference from local authorities. Mostly Shiite Muslims, their political allegiances to the powerful Hezbollah allow them to go against local authorities without fear of consequences’. They have thus disrupted the established hierarchical order and became the sole managers of the refugee crisis in their district, disregarding laws and regulations on housing and employment, overlooking ethics, and applying their own laws solely to maximize their profits. Yet, these practices include a number of advantages.

One of the most prominent consequences of the authorities’ inability to uphold the law is that Lebanese property owners informally divide dwellings into smaller spaces to maximize profitability. They often forge illegal rent-agreement documents that allow many families to rent the same space. These unlawful practices are convenient to the Syrian inhabitants because, as Adnan, a young refugee in Nabaa, claims, ‘they allow [them] to rent affordable spaces and share the cost of rent with other Syrian families’.

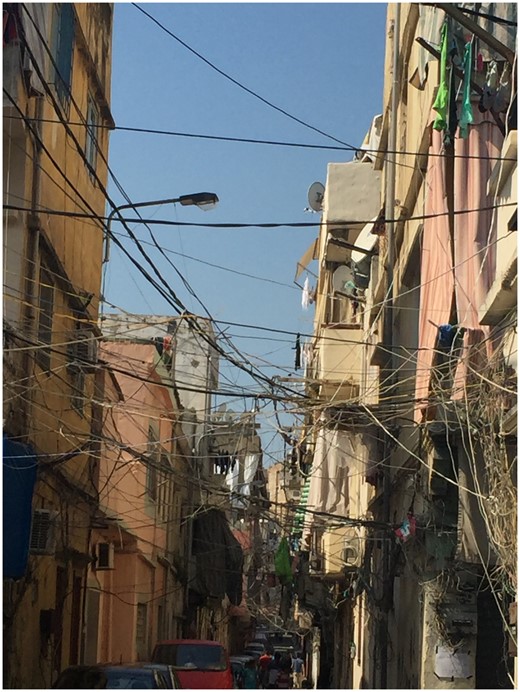

The mutual support between Syrian families highlights another advantage that Syrians in Nabaa benefit from and confirms that refugees’ greatest support system remains their social networks (Dionigi 2016). Over the years, Nabaa has become home to a large community of Syrian migrants, and many Syrian refugees have moved to the neighbourhood to join family and friends who settled in before the war. They settled there in hopes of finding affordable dwellings and job opportunities. Many have been successful, in part due to the support of their social connections. Nabaa is also home to migrant workers of other nationalities. Syrian residents are hence able to escape the stigma of refugeeness and assimilate themselves into the local population more easily than in areas predominantly inhabited by Lebanese (Figure 5).

Finally, Nabaa has acquired a high profile in the humanitarian community due to the large number of refugees established in the area. It has turned into a humanitarian hub, benefiting from international aid, despite the gradual overall reduction in international funding allocated to Lebanon. This situation makes it more attractive to refugees than other Lebanese localities. Yet, there are also many downsides to refugees’ living conditions in Nabaa.

Instability, Precarity, and Insecurity: The Price of Hospitality

In most cases, Syrian renters replace Lebanese tenants who have been expelled from their apartments on false pretences. For Lebanese property owners, this is an opportunity to increase profits through two practices: first by dividing apartments into many small rooms with makeshift kitchens and toilets, and illegally renting each room as a separate property, and second, by renting spaces to several Syrian families who, unlike Lebanese residents, agree to accommodate this multifamily living style and subsequently can afford to pay higher rents than single Lebanese families. Though these practices, as described earlier, can be advantageous for some refugees, they are also predatory practices that force both the host community and the refugees to accept poor living conditions in unsuitable, overpriced, and overcrowded spaces.

Refugees’ conditions in Nabaa have also increased the resentment local residents feel towards them. Tensions have grown between refugees and working-class Lebanese people, because Syrians have been replacing Lebanese workers in low-skilled jobs. They accept lower wages and tolerate more gruelling work. In commercial spaces, they have replaced local shop tenants. The Lebanese people we interviewed often express feeling expropriated and dispossessed of their own neighbourhood, where they have become a minority. 'The [Lebanese] landlord lied when he told me that we had to move out because his son was getting married. Afterwards, we found out that the landlord had rented our house to Syrians. We hate them. Write that down, that we hate them, and let everyone read it. They rob us of our homes, they rob us of our country’ claimed one Lebanese participant.

As for refugee spaces, they are usually in poor condition. Aside from in divided apartments and rooms, some refugees live in the backrooms of commercial spaces, in basements, on makeshift mezzanines, and in added structures on buildings rooftops. These spaces are often overcrowded, insalubrious, and sometimes have no natural light or ventilation (Figures 6 and 7). With little to no municipal oversight on rent agreements, prices are usually extremely high, and evictions are frequent. One of our respondents told us: ‘All the [rent] agreements are invalid. If anyone is willing to pay more than me, or if the owner doesn't like me anymore, we are kicked out straight away’. Moreover, Syrians who rent commercial spaces informed us that on top of the rent, they are compelled to pay a percentage of their business profits to Lebanese landlords.

A Commercial Space with a Living Space in the Backroom

Source:Kikano (2017).

Makeshift Toilet and Kitchen in the Backroom of a Commercial Space

Source:Kikano (2017).

Safety is also an issue. Local mafias control the neighbourhood. Verbal and physical abuse of Syrians is commonplace. Mohammad, another refugee, told us that certain roads are no-go zones for them. ‘My cousin was just passing by’, he said. ‘He was attacked by a Shia gang. Thugs. They stabbed him with a knife. The police knew but they did nothing’. Syrians’ institutional precariousness prevents them from seeking the protection of local authorities. It also restricts their freedom of movement. As such, they have become segregated in Nabaa’—a prison whose invisible walls are maintained by the illegality of their status.

The neighbourhood’s sudden overpopulation has had a negative impact on services and infrastructure. As detailed in a report by UN-Habitat, electricity and water shortages are frequent. Garbage has piled up as a result of the increasing amount of waste produced (and because waste collection has been increasingly sporadic following Lebanon’s 2015 waste crisis). The overall poverty and unemployment levels have risen significantly (UN-Habitat 2017). According to the World Bank (2019), ‘it is estimated that as a result of the Syrian crisis, some 200000 additional Lebanese have been pushed into poverty, adding to the erstwhile 1 million poor. An additional 250000–300000 Lebanese citizens are estimated to have become unemployed, most of them unskilled youth’ (World Bank 2019). The influx of refugees has also been detrimental to the local economy, as most residents’ income is spent only on basic needs, rent, and services (Zetter et al. 2014). This situation characterizes Nabaa’ and other neighbourhoods with a high refugee density (Table 2).

Benefits and Drawbacks of Policies of Exclusion on Refugees’ Living Conditions

| Consequences of adopted policies . | Benefits . | Drawbacks . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Security | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Livelihood opportunities | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Social and cultural dimension | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Space permeability | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Availability of services and infrastructure | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Impact on natural and built environment and landscape | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

| |

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Consequences of adopted policies . | Benefits . | Drawbacks . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Security | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Livelihood opportunities | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Social and cultural dimension | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Space permeability | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Availability of services and infrastructure | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Impact on natural and built environment and landscape | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

| |

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

Benefits and Drawbacks of Policies of Exclusion on Refugees’ Living Conditions

| Consequences of adopted policies . | Benefits . | Drawbacks . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Security | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Livelihood opportunities | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Social and cultural dimension | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Space permeability | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Availability of services and infrastructure | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Impact on natural and built environment and landscape | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

| |

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Consequences of adopted policies . | Benefits . | Drawbacks . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Security | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Livelihood opportunities | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Social and cultural dimension | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

|

| |

| Space permeability | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Availability of services and infrastructure | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

|

|

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

| Impact on natural and built environment and landscape | Dalhamieh Informal Settlement |

| |

| Nabaa’ Urban Neighbourhood |

| ||

Discussion: The Main Outcomes of Policies of Exclusion

Fragmented Governance in a Refugee Crisis

Some political scientists acknowledge that governments’ ‘politics of doing nothing’ can sometimes be deliberate and produce negative outcomes (McConnell and t' Hart 2014). This analysis of the politics of inaction helps us understand why, despite the seemingly different Lebanese policies before and after 2014, there is strong continuity between them. Both seek to prevent the permanence of refugees’ stay in the Lebanese territory and deploy the same strategy of exclusion. Hence, the Lebanese government’s absenteeism before 2014 in managing the refugee situation can be seen as an implicit form of exclusion, just as much as the restrictive regulations against refugees adopted by the government at the end of 2014.

The government’s disengagement and its unwillingness and incapacity to plan for a protracted situation led to the decentralization of responses (Mourad 2017). According to Shibli (2014) and Harb and Atallah (2015), decentralized approaches and the engagement of municipal authorities in managing the refugee crisis made service provision more effective and more context-specific (Shibli 2014; Harb and Atallah 2015). But despite the undeniable importance of local resources, this decentralization disrupted the traditional distribution of power leading to dysfunctions in local governance structures. It further strengthened the role of municipal authorities and established their independence in the management of the crisis. Local policies were dissimilar and varied from totally restrictive to very tolerant. As one would expect, Syrian refugees concentrated in areas where they were allowed to settle and where they could find jobs. Nabaa became one of these areas with high refugee density. Refugees' concentration strained services and infrustructure and led to competition with Lebanese residents for affordable housing and jobs, creating tension between the Lebanese and Syrian communities. Many Lebanese said they felt they had been dispossessed of their own neighbourhood. This feeling of dispossession increased their resentment of Syrians.

The ‘Freedom’ to Settle

The non-encampment policy, another manifestation of the government’s disengagement, gave refugees the ‘freedom’ to settle wherever they wanted. But with no other plans in place for their settlement, it was a poisonous gift that made them responsible for finding their own shelter at extortionate rates.

Similar to most displaced people, Syrians were deprived of the right of legal possession (or rent) of space, a right exclusive to citizens and foreign elites in most countries around the world (Massey 1995; Kibreab 1999). But despite refugees’ precarious situation, they sometimes developed a strong sense of appropriation and belonging. Space appropriation is noticeable in the Dalhamieh settlement. It is shown in refugees’ discourses through connotations of possession, and in their territorialized behaviours, such as protecting the settlement from outsiders’ intrusions and limiting access to inhabitants only. It is also perceptible in the cultural patterns that refugees reproduce. We find that their appropriation essentially results from the power and control they exert on their spaces. Our finding validates the established iterative correlation between power and space identity (Ripoll and Veschambre 2005; Pol 2006) and demonstrates that this correlation is also valid in vulnerable contexts of displacement.

In contrast with Nabaa’, in the Dalhamieh settlement, the distance from neighbouring villages and relative invisibility allowed refugees to feel safe and secure. Yet, they still underwent two evictions, in 2012 and 2015. Without legal rights over their spaces, their appropriation was no more than a psychological form of belonging with no factual implications.

Many refugees in Nabaa’ also underwent repeated evictions. They live in fear and are often at risk of hostility from certain members of the Lebanese community. For political reasons, the municipality of Burj Hammoud is unable to protect them. Most of these refugees are in a more precarious situation than those in the Dalhamieh informal settlement, even though this form of settlement is often associated with extreme poverty, given its ephemeral structure and the impermanent materials used for its construction. We thus challenge previous studies that have linked refugees’ vulnerability to the type of their settlement (Harrell-Bond et al 1992; Van Damme 1995; Black 1998). We find that housing and sheltering type is seldom the most decisive factor in relation to refugees’ vulnerability. We argue that refugees’ well-being is rather linked to their level of empowerment and to their inclusion in the public and urban systems of the host state. Our results align with prior research on the inconsistencies of host nations in their claims of power and control over their territories, when these claims are based on the exclusion of the displaced (Darling 2017). They also confirm research that highlights the importance of the economic integration of protracted refugees (Jacobsen and Fratzke 2016).

Most Syrian refugees in Nabaa’, and many in Dalhamieh,are excluded from legal systems, which limits their freedom of movement. Consequently, the spaces they occupy are gradually transforming into concealed ghettos, producing the very outcome that Lebanon was trying to avoid when it banned camps. We thus endorse Agier’s (2009) account of how the social relegation of refugees leads to the segregation of their spaces.

Structured Vulnerabilities

Policies of exclusion also exacerbate socioeconomic stratification. Adopted policies organize Syrian refugees’ vulnerability and structure it to the benefit of local elites. These policies engender new categories of actors—employers, landowners, property owners, and, within the Syrian refugee community, the shaweesh—who control and exploit refugees, increasing their vulnerability, as well as that of the communities hosting them. Given the restrictions on residency and work permits, refugees have become illegal settlers who receive little to no protection from local authorities and are often left at the mercy of their employers and landlords.

At the same time, refugees’ institutional and social exclusion is contrasted by their inclusion in the local economy. Their contribution to the local economy takes place either through jobs they accept with low pay and difficult conditions, or through the exorbitant rents they pay for their living spaces. This finding prompts us to question whether policies of exclusion are adopted to pressure refugees to leave or, on the contrary, to make them stay in a manner that serves the interests of powerful stakeholders.

Even so, and whatever the true reasons behind the adopted policies, the return of Syrian refugees is and will still be premature as long as the Syrian regime will not clearly express its will to welcome them, guarantee their safety, and ensure the availability of services and livelihood opportunities for them. Moreover, as it has been proven in previous studies (Van Hear 2006; Massey 2010), increasing refugees’ vulnerability prohibits them from resettling or returning to their country of origin. Future prospects are that the fragility of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, a country now facing bankruptcy and the collapse of its political system, will be further increased. Those who have the financial means—and the potential to become autonomous and beneficial to the country—will leave. Only the poorest will stay. They will become a heavier burden on the country, an easily exploitable population, and competition for an increasingly impoverished Lebanese population.

The study has several limitations, but the most notable is the vulnerability of most refugees interviewed and their fear of reprisal from other stakeholders: the shaweesh, landowners and employers, local community members, and local authorities. This limitation restricted us in our choice of respondents, because the most vulnerable refugees were the least keen to participate in our group discussions. Moreover, collecting data in Dalhamieh was particularly challenging because, after two evictions, refugees became suspicious and were reluctant to communicate. As for Nabaa, specific questions on rent agreements or on the transformation of informal spaces were not well received by most Lebanese owners. We were advised that asking such questions threatened the local community’s interests and therefore jeopardized our personal security.

Conclusion: National Policies of Exclusion or Local Power of Control?

By engaging in the debate on the formation and transformation of refugee spaces, this article contributes to a growing literature on refugee hosting and settlement policies by going beyond the reductive narrative of refugee exclusion. Based on a qualitative exploratory approach in two longitudinal case studies—an informal settlement and an urban neighbourhood—this study shows that excluding Syrian refugees from national and formal systems increases their vulnerability, thereby reducing the likelihood of repatriation or resettlement. It also demonstrates how national policies of exclusion and/or state absenteeism generate local power of control. In other words, the absence of involvement on behalf of the host state often coincides with the appearance of a new category of actors: employers and private landowners, who exploit refugees for their own gain. This article also shows that refugees’ well-being seldom depends on the type of their settlement. Their well-being depends on their empowerment and their inclusion in legal structures. Moreover, exclusion and irregular institutional status limits refugees’ movements and leads to the ghettoization of their spaces, an outcome that Lebanon, like other host countries, is trying to avoid. Refugee spaces seldom remain ‘temporary’, despite official insistence on perceiving them as such. We argue that these protracted ‘short-term’ solutions ought instead to be integrated within urban systems.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the Canadian Social Sciences Human Research Council (SSHRC) for supporting my PHD research project through the Joseph-Armand Bombardier scholarship. I would also like to thank Œuvre Durable for their scholarship in support of this article.

References

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL (

CORPUS LEVANT TEAM (

GOVERNMENT OF LEBANON & THE UNITED NATIONS (

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH (

LEBANON HUMANITARIAN INGO FORUM (

NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL and INTERNATIONAL RESCUE COMMITTEE (

SYRIAN LEBANESE HIGHER COUNCIL (

UN-HABITAT (

UNHCR (

UNHCR (

UNHCR (

UNHCR (

UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP and INTER-AGENCY COORDINATION LEBANON (

UNITED NATIONS (

WORLD BANK (

WORLD BANK (

WORLD BANK (