-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Christer A Flatøy, I am not an employee, am I then a professional? Work arrangement, professional identification, and the mediating role of the intra-professional network, Journal of Professions and Organization, Volume 10, Issue 2, June 2023, Pages 137–150, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joad012

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Professions face challenges from proliferation and dilution, two processes that challenge our understanding of what a profession is and what it means to be a professional. As a response, profession scholars are paying increasing attention to how individuals come to see themselves as a professional. We contribute to this evolving literature by investigating the relationship between work arrangements, that is, freelancing and employment, and professional identification. In so doing, we pay particular attention to the mediating role of an intra-professional network and three aspects that characterise such a network. We sample from journalists to investigate the relationships in question and employ structural equation modelling to test our hypotheses. We found no direct relationship between work arrangements and professional identification. However, we do observe that freelancers’ intra-professional network density is lower than that of employees. The consequence of this mediating mechanism, we found, was that they identified less with their profession than employees did. This paper shows that the type of work arrangement has important implications for professional identification.

INTRODUCTION

Profession scholars face challenges from what we can refer to as proliferation and dilution. While professions were once a select group of occupations ‘easily’ distinguished by their institutional capability to enforce social closure (Saks 2016), this select group of occupations has grown significantly during the last decades (Gorman and Sandefur 2011; Kirkpatrick, Aulakh and Muzio 2023). As an apt example of how professions and professional work are diluted, Galperin (2017) documents how professional services are now mass-produced by non-professional workers, drastically challenging our understanding of what it means to be a profession and a professional.

As a response to this proliferation and dilution, many profession scholars have turned to neo-Institutional theories and focused on professionalization processes rather than on the traits that characterize professions (such as their capability to enforce social closure) (Muzio, Brock and Suddaby 2013; Suddaby and Muzio 2015). One of the central concerns in the literature on professionalization processes is how individuals develop a professional identity and an identification with this identity (Barbour and Lammers 2015; Bévort and Suddaby 2016; Ahuja, Nikolova and Clegg 2017).

When individuals identify with a profession, they are guided by the epistemic and moral properties associated with that profession (Kärreman and Alvesson 2004; Alvesson, Kärreman and Sullivan 2015) and become more supportive of the community and the epistemic and moral properties that constitute their profession (Wright, Zammuto and Liesch 2017). In other words, were individuals not to identify with their profession, professions would represent little more than a label. Thus, individuals’ identification with professions is a prerequisite for the survival of professions.

This article investigates the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification by sampling from freelancing- and employed journalists. One of the most significant changes to affect the world of work since the 20th century, differentiating the ‘new’ world of work from the ‘old’ (Spreitzer, Cameron and Garrett 2017), has been the increasing trend of externalizing work outside of organizational boundaries through nonstandard work arrangements (Barley, Bechky and Milliken 2017). Freelancing is particularly relevant in this regard (Ashford, Caza and Reid 2018). Freelancers drive the resilient and sustained surge in nonstandard work amongst highly skilled, often professional, workers (Katz and Krueger 2019; Cross and Swart 2021). In terms of how work is organized, freelancing is the contrasting arrangement to permanent employment (Cappelli and Keller 2013). This makes freelancers a theoretically and empirically interesting group of workers to compare employees with. Yet, despite their increasing relevance, freelancers remain understudied and under-theorized in the profession literature (Cross and Swart 2021).

Freelancers are sometimes portrayed as ‘free agents’ (Pink 2001)—atomized workers that prefer to spend their lives in solitude in the job market as ‘hired guns’ (Inkson, Heising and Rousseau 2001; Barley and Kunda 2004) and ‘lone wolfs’ (Cross and Swart 2021). Viewed in this light, freelancing could reduce individuals’ professional identification by disrupting their relation to a professional community and the properties associated with this community. Recent studies have developed theories implying that this is the case, that many freelancers develop work identities of a more ‘fluid’ and personalized form than those of employees (Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski 2018; Maestripieri 2019; Cross and Swart 2021). However, these studies do not investigate if freelancers identify less with their profession than employees do, which is, arguably, the primary concern in terms of how freelancing may challenge the foundation of professions.

To better understand the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification, we pay particular attention to the mediating role of intra-professional networks (IPNs). We know that identity construction is a highly localized process that depends on social relations and daily interactions (Sluss and Ashforth 2007; Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno 2016; Bévort and Suddaby 2016), where members of in-groups are the primary validators of professional identities (Van Maanen 1975; Ashforth and Kreiner 1999). However, we know less about how IPNs mediate the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification. Building on insights from qualitative studies of freelancers’ professional networks, we argue that their IPN, in terms of three defining aspects, is of lower quality than those of their employed professional peers.

We conducted our study using a sample of 1,031 journalists, including 113 freelancers. Several factors make journalism an opportune setting for investigating the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification, despite journalism sometimes being classified as a semi-profession due to the absence of social closure (Aldridge and Evetts 2003). Journalists speak of and view themselves as professionals (Aldridge and Evetts 2003; Berry 2016; Raemy 2020) and identify with what they see as a profession (Russo 1998). Journalists also have a solid knowledge base and adhere to a comprehensive and strong set of professional norms (Aldridge and Evetts 2003; Raemy 2020; Weaver and Willnat 2020). Therefore, moving beyond a trait-based understanding of professions to a neo-Institutional and discursive understanding (Saks 2016), it is reasonable for profession scholars to treat journalists as professionals and acknowledge that they do experience professional identification and not reserve studies of professional identification for practitioners of more established professions (Abbott 1998; Aldridge and Evetts 2003; Galperin 2017; Cross and Swart 2021).

Moreover, freelancing is predicted to become widespread in more professions in the years to come (Katz and Krueger 2019). Because journalism is a (semi-)profession where freelancing has been widespread and common for decades (Gynnild 2005), studying professional identity formation among journalists can provide valuable insights into dynamics that can arise in other professions where freelancing is or becomes widespread and common. In short, journalism offers a theoretically and empirically relevant setting for investigating professional identity formation, particularly among freelancers.

This article offers two key contributions to the profession literature. While building on valuable insights from three qualitative studies (Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski 2018; Maestripieri 2019; Cross and Swart 2021), this article nuances theory developed in these studies. Specifically, through different lines of theorization, these studies suggest that the nature of their work arrangement decreases freelancers’ professional identification; however, our results indicate that freelancers’ professional identification is more robust to the requirements of their work arrangement than what is suggested by these studies. Second, while much has been written on how professional networks induct novel practitioners into a profession (Spreitzer, Cameron and Garrett 2017), no study has investigated how IPNs bridge individuals’ work arrangements and professional identification. Our results highlight the importance of the density of IPNs in this regard, a finding that corroborates and nuances the theory on the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification (Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski 2018). In sum, this paper provides nuanced and new insights into the profession literature.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Professional identification

What constitutes a profession is disputed. A common starting point is that professions are constituted by a community of practitioners that embodies a particular set of epistemic and moral properties (Abbott 1998). Beyond this, the popular neo-Institutional school of professions (Muzio, Brock and Suddaby 2013; Saks 2016) portrays professions as dynamic systems embedded in various institutional contexts that change over time (Suddaby and Muzio 2015). Thus, acknowledging the impact of time-space heterogeneity (Faulconbridge and Muzio 2012), few traits are considered universal or everlasting for professions. With this acknowledgement, the profession literature has evolved from focusing on the traits characterizing professions to focusing on professionalization processes (Suddaby and Muzio 2015), such as how individuals develop their professional identification (Barbour and Lammers 2015).

Professional identification refers to the extent to which individuals have internalized a professional identity (Ashforth, Harrison and Corley 2013). Professional identities are a form of social (as opposed to personal) identities, that is, self-referential descriptions socially shared among and unique for members of a given profession (Barbour and Lammers 2015). The self-referential descriptions emerge from the ‘essences’ that characterize a social group (Ashforth, Harrison and Corley 2008), which in the case of professions are the epistemic and moral characteristics associated with the professional community that constitutes the profession (Ashforth, Harrison and Corley 2013; Barbour and Lammers 2015). When individuals internalize these ‘essences’, they come to experience professional identification.

Research rooted in social identity theory has uncovered three dimensions that characterize identification as a psychological experience. First, identification is characterized by a cognitive awareness of belonging to a social group (‘I am a journalist’). Second, this cognitive awareness is accompanied by an evaluative assessment of this belonging (‘As a journalist, I should behave this way’). Third, identification entails an experience of emotional investment in the belonging to a social group (‘I feel good about being a journalist’) (Ashforth, Harrison and Corley 2008).

Freelancing and professional identification

Formally, freelancers differ from employees with regard to two key dimensions: contract and control. Employees have an employment contract, while freelancers contract with their clients on a piece-rate basis. Consequently, freelancers have directive control of their work while employees do not (Cappelli and Keller 2013). More fundamentally, freelancers spend their work life in the job market while employees spend theirs in organizations (Barley and Kunda 2004).

Individuals’ work contexts matter for how they relate to their profession (Suddaby, Gendron and Lam 2009; Barbour and Lammers 2015). Three recent studies have theorized that freelancers develop work identities of a ‘fluid’ (Cross and Swart 2021) and personalized (Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski 2018; Maestripieri 2019) form. That they develop ‘fluid’ and personalized work identities implies that freelancers do not internalize the professional identity that is socially shared among professional peers, or at least that they do so to a lesser extent than employees—that is, that freelancers experience a lower level of professional identification than what employees do. Both Maestripieri (2019) and Cross and Swart (2021) argue that this happens because freelancers adhere to a market logic to the detriment of their professional identification.

We know that a life in the job market will for many freelancers necessitate a predominant focus on a market logic to land jobs (Barley and Kunda 2004). On the receiving end of their services, Zadik et al. (2019) found that clients prioritize adaptability to organizational demands well ahead of professionalism when hiring freelancers. More, as Maestripieri (2019) shows, a life in the market for some entails doing whatever work is available, professional or not, through ‘any’ means necessary, professional or not. Freelancers, that is, have to be what Cross and Swart (2021, p. 1710) refer to as ‘chameleon[s]’.

Thus, life in the market could lead to reduced professional identification, as freelancers think and act less like typical professionals. However, while research has shown freelancers to emphasize different logics than employees (Maestripieri 2019; Cross and Swart 2021), we are still left with the question: Is life in the job market less conducive to professional identification than life in the organization? Following the arguments and theorization of Cross and Swart (2021) and Maestripieri (2019), as summarized above, we are led to believe that:

H1: Freelancers identify significantly less with their profession than their permanently employed peers do.

Social networks and professional identification

Professional communities and the networks and interactions therein are vital components in the formation of professional identities (Ashforth, Sluss and Harrison 2007; Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno 2016). In an exploratory study of how freelancers develop their work identities, Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski (2018) demonstrated how vital their lack of a network of professional peers is in this process. None of their informants had regular peer groups that anchored their work identity, a lack that accompanied the absence of an organizational social context. As one of their informants told Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski (2018, p. 141): ‘The kind of community that’s created for people with policies and procedures in the organisation; that is the container I have to create for myself’. As this statement indicates, the informants of Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski (2018) developed more personal rather than professional networks. This led their informants to develop more personal work identities rather than internalizing socially shared professional identities (Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski 2018), implying a low level of professional identification.

Research has shown that ‘in-group’ members, professional peers, are particularly important facilitators of professional identification. Professional peers socialize individuals to ‘truly’ become professionals (Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno 2016), and they serve as the primary external validators of a professional identity (Van Maanen 1975; Ashforth and Kreiner 1999; Alvesson, Kärreman and Sullivan 2015). These insights highlight the relevance of IPNs as a mediator in the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification. To investigate this further, we relied on social network theory, a common approach in identification studies (Jones and Volpe 2011; Walker and Lynn 2013).

Accordingly, social networks consist of actors connected by ties of a certain nature (Borgatti and Halgin 2011). Note that this study focuses on professionals’ egocentric networks, that is, individuals’ unique networks, as opposed to a network focus. This entails focusing on that part of individuals’ networks that directly influences individuals (Marsden 1990; Jones and Volpe 2011). With this in mind, three aspects of a social network can be inferred from the definition above, all of which have been shown by research to be positively associated with identification (McFarland and Pals 2005; Jones and Volpe 2011; Graupensperger, Panza and Evans 2020). The first is the network size, which corresponds to the number of actors to whom an individual is connected (Ibarra 1995). The second is the network strength, which, according to Granovetter (1973), corresponds to the frequency of interaction between an individual and other actors in the network. The third aspect is density, which, from an egocentric network perspective, refers to the distance between an individual (the ego) and the other actors in that network (Jones and Volpe 2011).

Freelancers, permanent employees, and intra-professional networks

Regarding the size of freelancers’ IPNs, research tends to emphasize how important networking is for freelancers and their careers (Van den Born and Van Witteloostuijn 2013). Yet, research also indicates that it is hard for freelancers to develop lasting ties with professional peers. Based on an extensive ethnographic study, Kunda, Barley and Evans (2002) concluded that the majority of the freelancers they interviewed came to accept the ‘the existential status of a perpetual stranger’ (p. 250, see also Barley and Kunda (2004) and Osnowitz (2010)). It is therefore likely that freelancers meet more professional peers than their employed peers, but few meetings result in ties that last, thus limiting the size of their IPNs. On the other hand, employees will often develop lasting ties with long-term colleagues, many of whom will be professional peers. This leads us to the first hypothesis concerned with freelancers’ and employees’ IPNs:

H2A: Freelancers’ IPNs are significantly smaller than that of their permanently employed peers.

Regarding the strength of their ties with other actors in their IPNs, freelancers tend to have less frequent interactions with their professional peers than their employed peers. While some of the time spent in the job market is spent interacting with professional peers, much of it is spent in solitude or interacting with others outside of their own profession (Barley and Kunda 2004). In fact, many freelancers prioritize labour market intermediaries, online labour markets, and former clients when looking for jobs, suggesting that most of the time spent in the market is spent not with professional peers (Barley and Kunda 2004; Shevchuk and Strebkov 2018). As for employees, they generally dedicate their time fully to one organization (for a comparatively long time). This enables permanent employees to have consistent, continuous, and frequent interaction with other professional peers employed by the same organization. Based on these insights, we hypothesize as follows:

H2B: Freelancers’ IPNs have significantly weaker ties than do that of their permanently employed peers.

As for the density of their IPNs, compared to permanent employees, freelancers will often be less proximal to their professional peers. In her ethnographic study, Osnowitz (2010) discussed how the interaction between freelancers is inevitably competitive, indicating that freelancers hold each other at an ‘arm’s length’ distance. As for freelancers’ ties to their employed peers, several studies have found that freelancers are sometimes treated as an ‘underclass’ (Zadik et al. 2019, p. 40) and ‘servants’ (Barley and Kunda 2004, p. 215). Demonstrating this experience, in their study of interim/freelance managers, Inkson, Heising and Rousseau (2001) found that the most common on-the-job problem reported by their informants was that they were met with hostility and a lack of recognition in the companies they worked for. All of this suggests that freelancers often have more instrumental and less proximal ties with their professional peers than their permanently employed peers have with each other. This leads us to the following hypothesis:

H2C: Freelancers’ IPNs have a significantly smaller density than that of their permanently employed peers.

Intra-professional network and professional identification

As noted above, research has shown the three aspects of a social network, namely its size, strength, and density, to be positively associated with identification, and we believe this to be the case also for the relationship between an IPN and professional identification. Much of the research we discuss below is linked to a homophily line of argumentation, summarized as follows: like tends to attract and be attracted to like, and consequently become more like (Ibarra 1993b, 1995).

Regarding IPN size, individuals with comparatively large networks will be more in the centre of the social network/group wherein identity formation occurs (Ibarra 1993b). Individuals with relatively large IPNs will therefore likely already have internalized the social identity shared in that network/group and continue to do so, more than what individuals with smaller IPNs have and will do (Ibarra 1993b, 1995; Jones and Volpe 2011). Moreover, the larger the individuals’ IPNs, the more commitment individuals will likely experience toward their network because more actors are involved in evaluating the individual’s behaviour (McFarland and Pals 2005). This leads us to the following hypothesis:

H3A: The size of individuals’ IPNs is significantly and positively associated with their professional identification.

Regarding the strength of the ties in a network, interaction is a prerequisite for information sharing, without which individuals cannot exert influence on each other (Borgatti and Halgin 2011). Therefore, the more frequently individuals interact with their IPN, the greater influence actors in their IPN can exert on them (Brass et al. 2004). Demonstrating this, in a study of Amway distributors, Pratt (2000) found that distributors with strong ties with their sponsors strongly identified with Amway, while distributors with distant or infrequent interaction with their sponsors disidentified with Amway. Based on these insights, we hypothesize that:

H3B: The strength of the ties in individuals’ IPNs is significantly and positively associated with their professional identification.

As for the third aspect of an IPN, network density promotes a sense of oneness with a social group. The smaller distance between actors in a network, the easier it is for them to share information among themselves and the greater influence they can have on each other (Sluss and Ashforth 2008). A smaller distance would also suggest a more positive and trusting relationship, which is more conducive to internalizing a professional identity (Jones and Volpe 2011). In addition, as pointed out by Jones and Volpe (2011), individuals who are perceived to not conform to a social identity in a social network with high density are particularly at risk of being met with repercussions aimed at countering this lack of conformity. The closer workers are to each other, that is, the more they will likely induce each other to internalize a socially shared identity. Based on these insights, the final hypothesis is as follows:

H3C: The density of individuals’ IPNs is significantly and positively associated with their professional identification.

METHOD

Sample

To gather the necessary data, we distributed a questionnaire to active, that is, non-retired and non-student, members of two trade unions for journalists in Norway. One of these trade unions represents the vast majority of journalists in Norway. The second trade union is a niche organization with around 200 members. Besides size, the key difference between the two trade unions is that the smaller union is primarily oriented toward writers of cultural content. Therefore, it is open to non-journalists (e.g. professors), provided they write such content (note that non-journalists were excluded from our sample). The two trade unions have in total 6,500 active journalists as members, around 650 of whom are freelance journalists.

A total of 1,860 members (29% of the active members of the two trade unions) responded to the survey. Due to some incomplete responses to questions used in this study, the usable sample consisted of 1,031 responses (15.9 %). This included 113 respondents (10.9 % of the usable sample) who were exclusively or primarily freelancing, meaning they did not combine freelancing with permanent employment. When compared with registry data from the Norwegian Tax Authorities covering the population of journalists in Norway—out of which freelance journalists represent approximately 8%—we find that our sample generally corresponds with the population of journalists in Norway on key demographic features: The average age of the journalist population was 45 in 2021, while the sample average was 41–50; 54% of the population were women compared to 50% in our sample; average income in 2018 was 655,427 NOK compared to 500,000–700,000 NOK in our sample; and the average level of education was a bachelor degree both in the population and in our sample.

The questionnaire, issued in Norwegian, was distributed in the final months of 2021. Before distributing it, the author and two researchers external to this study independently translated the original English items into Norwegian. In the few cases of discrepancy between the translations, the author and one of the external researchers settled the discrepancy by determining which of the options would be perceived as most natural and semantically correct for a Norwegian sample. The final questionnaire was inspected by representatives of the unions and by one freelance journalist. During this inspection, the reviewers were instructed to pay particular attention to formulations and the choice of terms. The inspectors had no comments on these.

Measures

Dependent variable

Professional identification was measured by extending on Mael and Ashforth (1992)’s scale for organizational identification and adapting it to the relevant target (journalism). An example item from this scale is: ‘When I talk about journalists, I usually say “we” rather than “they”’. Mael and Ashforth’s (1992)’s scale is rooted in social identity theory, a theory concerned with the extent to which individuals experience social belonging, among other experiences, and the scale aims to measure the extent to which individuals identify with social groups such as professions (Ashforth et al. 2013). It has become one of the most widely used and, according to a meta-analysis by Riketta (2005), advantageous approach to measuring identification. However, the scale is not without its caveats. As Edwards (2005) and Van Dick (2001) noted, the scale mainly taps into the affective and evaluative dimensions of identification and neglects the cognitive dimension. To account for this, we supplemented our scale with two items suggested by Van Dick et al. (2004) to measure the cognitive dimension of identification. Adapted to our target, one example item is: ‘I identify myself as a journalist’. A total of eight items (see Supplementary Appendix A) were used to measure professional identification, and they were scored according to a 5-point Likert-type scale anchored by ‘Strongly disagree’ and ‘Strongly agree’.

Mediating variables

The three aspects of IPNs discussed above were measured. As has long been standard in social network research (see Ibarra 1993a; Morrison 2002; Jones and Volpe 2011), one item was used to measure each of the aspects of a social network. While some critics have argued that using single items to measure sociometric constructs is equivalent to doing so for psychometric constructs, a review, and empirical studies have established that single items can be used to measure social networks, provided that respondents can recall and report their network ties correctly (Marsden 1990; Ibarra 1993a). Two steps were taken to facilitate the respondents’ recollection and reporting. First, as Ibarra and Andrews (1993) and Marsden (1990) recommended, no limit was implemented in the questionnaire for the potential size of the respondents’ networks. Second, when measuring the size of networks, the empirical focus was limited to professional peers with whom the respondents were also close friends. Focusing on peers who are also close friends, as opposed to every professional peer with whom they might be acquainted, should assist respondents’ recollection and give a more reliable measure (Carpenter, Li and Jiang 2012). This delineation also fits with our focus on the egocentric network of professionals, that is, that part of their social network that directly influences them.

With the insights above in mind, the following items were utilized. First, to measure IPN size, which is determined by the number of actors someone is connected to (Carpenter, Li and Jiang 2012), the respondents were asked ‘How many close friends do you have who work as journalists?’ This item was scored continuously, without any upper boundary imposed by the questionnaire. More than 97% of the respondents responded that they were close friends with ten or fewer professional peers. To further strengthen the reliability of this measure, the remaining ~2% were coded as missing and discarded from this study.

Second, for IPN strength, respondents’ frequency of interaction with other actors in the network was measured, as recommended by Granovetter (1973) (see also Arnaboldi et al. 2016). The item used to do so was inspired by Ibarra (1995), although it was adapted to our setting as follows ‘How often do you meet other journalists outside of working hours?’. The item was scored in the following way: ‘Never’ (0), ‘Less than once a month’ (1), ‘Once a month’ (2), ‘Several times a month’ (3), ‘Once a week’ (4), ‘Several times a week’ (5), and ‘Every day’ (6).

The third aspect, IPN density, was more challenging to measure than the first two. Not every empirical study of egocentric networks has measured the network’s density (Jones and Volpe 2011), and among those that have, no approach is fit for universal usage. It was therefore necessary to design an item to measure IPN density specifically for this setting. Network density refers to the extent to which people in a network know each other (Jones and Volpe 2011), and scholars focusing on network density tend to use it to study how well networks facilitate information sharing (Carpenter, Li and Jiang 2012; Phelps, Heidl and Wadhwa 2012). Information sharing was therefore used as a proxy for density, and the respondents were asked ‘To what extent can you rely on other journalists for professional advice?’ This item was scored as follows: ‘Not at all’ (1), ‘To a small extent’ (2), ‘To a moderate extent’ (3), ‘To a large extent’ (4), and ‘To a very large extent’ (5).

Independent variable

The independent variable work arrangement contains two categories: Employee with open-ended contract (0) and Freelancer (1). To categorize respondents, they were asked ‘What is your primary work arrangement?’ and the questionnaire further specified that ‘By primary work arrangement, we refer to the work arrangement that you spend the most time on if you have several work arrangements’. In this sample, 29 respondents were primarily freelancers who sometimes worked as temporary employees. For some freelancers, mixing freelancing with temporary employment follows automatically from a regulation that states that workers physically located in an editorial newsroom should be classified as (temporary) employees. Since these 29 respondents self-identified as freelancers, they were grouped with the 84 who exclusively freelanced.

Control variables

Ten control variables were used. These were theoretically relevant, and several have been shown to be empirically relevant in previous studies of professional identification (Ashforth et al. 2013) and studies of freelancers’/independent contractors’ identification with targets at work (George and Chattopadhyay 2005). The first five related to the respondents’ work situation, while the remaining five were standard demographic and background variables. Related to work, these were years of experience as a journalist (continuous), years of experience with current work arrangement (continuous), work location (before the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns in Norway from March 2020) (distinguishing between ‘at an employer/client’s location’ (0) and ‘at a home office/remote (co)workspace’ (1)), working hours per week (categorical), job (distinguishing between those with the job title of ‘journalist’ (1) and those with other job titles and journalistic functions, such as ‘editor’, ‘news anchor’, or ‘photographer’ (0)). Related to demography and background, we controlled for gender, age (measured categorically, i.e. cat. 1: 18–20 years, cat. 2: 21–30 years, cat. 3: 31–40 years, etc.), level of education (categorical), type of education (‘other’ (0), ‘journalism’ (1)), and income (categorical).

RESULTS

Table 1 reports the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for the variables used in the analysis. In addition to the descriptive statistics reported above, Table 1 shows that the respondents’ average tenure as a journalist was 21.2 years, and the average experience with current work arrangement was 17.7 years. Moreover, 59% of the sample had a journalism education, 66% had the position of ‘journalist’, and 34% held different positions, for instance, ‘editor’. The average respondent worked 36–40 h a week (the standard work week in Norway), and 91% generally worked from the employer’s location (before the COVID-19 pandemic).

| Variables . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experience as a journalist | 21.99 | 11.28 | - | 0.81* | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17* | 0.82* |

| 2. Experience with current work arrangement | 17.69 | 11.00 | 0.81* | - | −0.15* | 0.06* | −0.02 | 0.15* | 0.74* |

| 3. Work location | 1.09 | 0.29 | 0.01 | −0.15* | - | −0.14* | 0.01 | −0.07* | 0.05* |

| 4. Working hours per week | 3.23 | 0.73 | −0.00 | 0.06* | −0.14* | - | −0.02 | 0.10* | −0.04* |

| 5. Position | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | - | 0.03* | 0.00 |

| 6. Gender | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.17* | 0.15* | −0.07* | 0.10* | 0.03* | - | 0.12* |

| 7. Age | 4.22 | 1.15 | 0.82* | 0.74* | 0.05* | −0.04* | 0.00 | 0.12* | - |

| 8. Income | 4.18 | 0.71 | 0.27* | 0.30* | −0.19* | 0.25* | −0.13* | 0.17* | 0.19* |

| 9. Level of education | 3.90 | 0.85 | −0.25* | −0.24* | 0.11 | −0.05* | 0.04* | −0.21* | −0.13* |

| 10. Type of education | 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.12* | −0.09* | −0.05* | 0.00 | −0.08* | −0.09* | −0.20* |

| 11. Work arrangement | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.01 | −0.20* | 0.70* | −0.26* | −0.05* | −0.08* | 0.06* |

| 12. Size of IPN | 3.00 | 2.63 | 0.05* | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07* | −0.11* | −0.05* | −0.06* |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 3.09 | 1.35 | −0.17* | −0.17* | −0.00 | 0.04* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.25* |

| 14. Density of IPN | 3.92 | 0.86 | −0.12* | −0.06* | −0.18* | 0.05* | −0.00 | −0.04* | −0.18* |

| 15. Professional identification | 3.24 | 0.57 | −0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | 0.06* | 0.06* | −0.12* | −0.08* |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 8. Income | - | −0.08* | −0.05* | −0.27* | 0.17* | 0.10* | 0.13* | 0.04* | |

| 9. Level of education | −0.08* | - | −0.01 | 0.11* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.03* | −0.09* | |

| 10. Type of education | −0.05* | −0.01 | - | −0.05* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.05* | |

| 11. Work arrangement | −0.27* | 0.11* | −0.05* | - | 0.05* | −0.01 | −0.24* | −0.05* | |

| 12. Size of IPN | 0.17* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.05* | - | 0.47* | 0.18* | 0.09* | |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 0.10* | 0.07* | 0.06* | −0.01 | 0.47* | - | 0.26* | 0.18* | |

| 14. Density of IPN | 0.13* | 0.03* | 0.07* | −0.24* | 0.18* | 0.26* | - | 0.14* | |

| 15. Professional identification | 0.04* | −0.09* | 0.05* | −0.05* | 0.09* | 0.18* | 0.14* | - | |

| Variables . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experience as a journalist | 21.99 | 11.28 | - | 0.81* | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17* | 0.82* |

| 2. Experience with current work arrangement | 17.69 | 11.00 | 0.81* | - | −0.15* | 0.06* | −0.02 | 0.15* | 0.74* |

| 3. Work location | 1.09 | 0.29 | 0.01 | −0.15* | - | −0.14* | 0.01 | −0.07* | 0.05* |

| 4. Working hours per week | 3.23 | 0.73 | −0.00 | 0.06* | −0.14* | - | −0.02 | 0.10* | −0.04* |

| 5. Position | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | - | 0.03* | 0.00 |

| 6. Gender | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.17* | 0.15* | −0.07* | 0.10* | 0.03* | - | 0.12* |

| 7. Age | 4.22 | 1.15 | 0.82* | 0.74* | 0.05* | −0.04* | 0.00 | 0.12* | - |

| 8. Income | 4.18 | 0.71 | 0.27* | 0.30* | −0.19* | 0.25* | −0.13* | 0.17* | 0.19* |

| 9. Level of education | 3.90 | 0.85 | −0.25* | −0.24* | 0.11 | −0.05* | 0.04* | −0.21* | −0.13* |

| 10. Type of education | 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.12* | −0.09* | −0.05* | 0.00 | −0.08* | −0.09* | −0.20* |

| 11. Work arrangement | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.01 | −0.20* | 0.70* | −0.26* | −0.05* | −0.08* | 0.06* |

| 12. Size of IPN | 3.00 | 2.63 | 0.05* | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07* | −0.11* | −0.05* | −0.06* |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 3.09 | 1.35 | −0.17* | −0.17* | −0.00 | 0.04* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.25* |

| 14. Density of IPN | 3.92 | 0.86 | −0.12* | −0.06* | −0.18* | 0.05* | −0.00 | −0.04* | −0.18* |

| 15. Professional identification | 3.24 | 0.57 | −0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | 0.06* | 0.06* | −0.12* | −0.08* |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 8. Income | - | −0.08* | −0.05* | −0.27* | 0.17* | 0.10* | 0.13* | 0.04* | |

| 9. Level of education | −0.08* | - | −0.01 | 0.11* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.03* | −0.09* | |

| 10. Type of education | −0.05* | −0.01 | - | −0.05* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.05* | |

| 11. Work arrangement | −0.27* | 0.11* | −0.05* | - | 0.05* | −0.01 | −0.24* | −0.05* | |

| 12. Size of IPN | 0.17* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.05* | - | 0.47* | 0.18* | 0.09* | |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 0.10* | 0.07* | 0.06* | −0.01 | 0.47* | - | 0.26* | 0.18* | |

| 14. Density of IPN | 0.13* | 0.03* | 0.07* | −0.24* | 0.18* | 0.26* | - | 0.14* | |

| 15. Professional identification | 0.04* | −0.09* | 0.05* | −0.05* | 0.09* | 0.18* | 0.14* | - | |

* indicate correlations significant at P < 0.05.

| Variables . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experience as a journalist | 21.99 | 11.28 | - | 0.81* | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17* | 0.82* |

| 2. Experience with current work arrangement | 17.69 | 11.00 | 0.81* | - | −0.15* | 0.06* | −0.02 | 0.15* | 0.74* |

| 3. Work location | 1.09 | 0.29 | 0.01 | −0.15* | - | −0.14* | 0.01 | −0.07* | 0.05* |

| 4. Working hours per week | 3.23 | 0.73 | −0.00 | 0.06* | −0.14* | - | −0.02 | 0.10* | −0.04* |

| 5. Position | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | - | 0.03* | 0.00 |

| 6. Gender | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.17* | 0.15* | −0.07* | 0.10* | 0.03* | - | 0.12* |

| 7. Age | 4.22 | 1.15 | 0.82* | 0.74* | 0.05* | −0.04* | 0.00 | 0.12* | - |

| 8. Income | 4.18 | 0.71 | 0.27* | 0.30* | −0.19* | 0.25* | −0.13* | 0.17* | 0.19* |

| 9. Level of education | 3.90 | 0.85 | −0.25* | −0.24* | 0.11 | −0.05* | 0.04* | −0.21* | −0.13* |

| 10. Type of education | 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.12* | −0.09* | −0.05* | 0.00 | −0.08* | −0.09* | −0.20* |

| 11. Work arrangement | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.01 | −0.20* | 0.70* | −0.26* | −0.05* | −0.08* | 0.06* |

| 12. Size of IPN | 3.00 | 2.63 | 0.05* | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07* | −0.11* | −0.05* | −0.06* |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 3.09 | 1.35 | −0.17* | −0.17* | −0.00 | 0.04* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.25* |

| 14. Density of IPN | 3.92 | 0.86 | −0.12* | −0.06* | −0.18* | 0.05* | −0.00 | −0.04* | −0.18* |

| 15. Professional identification | 3.24 | 0.57 | −0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | 0.06* | 0.06* | −0.12* | −0.08* |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 8. Income | - | −0.08* | −0.05* | −0.27* | 0.17* | 0.10* | 0.13* | 0.04* | |

| 9. Level of education | −0.08* | - | −0.01 | 0.11* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.03* | −0.09* | |

| 10. Type of education | −0.05* | −0.01 | - | −0.05* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.05* | |

| 11. Work arrangement | −0.27* | 0.11* | −0.05* | - | 0.05* | −0.01 | −0.24* | −0.05* | |

| 12. Size of IPN | 0.17* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.05* | - | 0.47* | 0.18* | 0.09* | |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 0.10* | 0.07* | 0.06* | −0.01 | 0.47* | - | 0.26* | 0.18* | |

| 14. Density of IPN | 0.13* | 0.03* | 0.07* | −0.24* | 0.18* | 0.26* | - | 0.14* | |

| 15. Professional identification | 0.04* | −0.09* | 0.05* | −0.05* | 0.09* | 0.18* | 0.14* | - | |

| Variables . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experience as a journalist | 21.99 | 11.28 | - | 0.81* | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17* | 0.82* |

| 2. Experience with current work arrangement | 17.69 | 11.00 | 0.81* | - | −0.15* | 0.06* | −0.02 | 0.15* | 0.74* |

| 3. Work location | 1.09 | 0.29 | 0.01 | −0.15* | - | −0.14* | 0.01 | −0.07* | 0.05* |

| 4. Working hours per week | 3.23 | 0.73 | −0.00 | 0.06* | −0.14* | - | −0.02 | 0.10* | −0.04* |

| 5. Position | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | - | 0.03* | 0.00 |

| 6. Gender | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.17* | 0.15* | −0.07* | 0.10* | 0.03* | - | 0.12* |

| 7. Age | 4.22 | 1.15 | 0.82* | 0.74* | 0.05* | −0.04* | 0.00 | 0.12* | - |

| 8. Income | 4.18 | 0.71 | 0.27* | 0.30* | −0.19* | 0.25* | −0.13* | 0.17* | 0.19* |

| 9. Level of education | 3.90 | 0.85 | −0.25* | −0.24* | 0.11 | −0.05* | 0.04* | −0.21* | −0.13* |

| 10. Type of education | 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.12* | −0.09* | −0.05* | 0.00 | −0.08* | −0.09* | −0.20* |

| 11. Work arrangement | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.01 | −0.20* | 0.70* | −0.26* | −0.05* | −0.08* | 0.06* |

| 12. Size of IPN | 3.00 | 2.63 | 0.05* | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07* | −0.11* | −0.05* | −0.06* |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 3.09 | 1.35 | −0.17* | −0.17* | −0.00 | 0.04* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.25* |

| 14. Density of IPN | 3.92 | 0.86 | −0.12* | −0.06* | −0.18* | 0.05* | −0.00 | −0.04* | −0.18* |

| 15. Professional identification | 3.24 | 0.57 | −0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | 0.06* | 0.06* | −0.12* | −0.08* |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 8. Income | - | −0.08* | −0.05* | −0.27* | 0.17* | 0.10* | 0.13* | 0.04* | |

| 9. Level of education | −0.08* | - | −0.01 | 0.11* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.03* | −0.09* | |

| 10. Type of education | −0.05* | −0.01 | - | −0.05* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.07* | 0.05* | |

| 11. Work arrangement | −0.27* | 0.11* | −0.05* | - | 0.05* | −0.01 | −0.24* | −0.05* | |

| 12. Size of IPN | 0.17* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.05* | - | 0.47* | 0.18* | 0.09* | |

| 13. Strength of ties in IPN | 0.10* | 0.07* | 0.06* | −0.01 | 0.47* | - | 0.26* | 0.18* | |

| 14. Density of IPN | 0.13* | 0.03* | 0.07* | −0.24* | 0.18* | 0.26* | - | 0.14* | |

| 15. Professional identification | 0.04* | −0.09* | 0.05* | −0.05* | 0.09* | 0.18* | 0.14* | - | |

* indicate correlations significant at P < 0.05.

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis for the eight-item measure of professional identification. This process yielded a satisfactory composite reliability score of.763. The resulting goodness-of-fit statistics were initially sub-par; however, calculations in Stata 17.0 indicated that modelling covariation between several items used to measure the construct better represented the measurement model (see Supplementary Appendix B). With these modifications implemented, our measurement model attained satisfactory goodness-of-fit statistic scores (Kline 2015): RMSEA = 0.079, CFI = 0.951, TLI = 0.902, SRMR = 0.045, x2 = 116.148, P = 0.000.

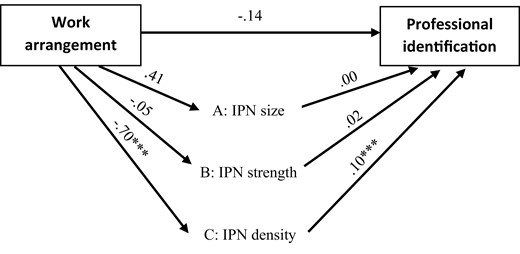

The model we analysed is a multiple mediation model equivalent to the one shown in Fig. 1 below, with the addition of control variables added with a path to the dependent variable. A bootstrap estimation procedure with 50,000 replications was used to estimate standard errors and confidence intervals (CIs). The CIs we report are bias-corrected, which, according to MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams (2004), are the most accurate CIs. Table 2 below shows the structural equation modelling analysis results, and Fig. 1 summarizes the key results.

| Variables (dependent variables in italics in table) . | Path coefficient . | SE . | Boot BC CI . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL . | UL . | |||

| Professional identification | ||||

| Experience as a journalist | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Experience w/ current work arrangement | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Work location | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Working hours per week | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| Position | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.15 |

| Gender | −0.16*** | 0.04 | −0.25 | −0.08 |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Level of education | −0.08*** | 0.02 | −0.13 | −0.04 |

| Type of education | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Work arrangement | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.32 | 0.04 |

| Size of IPN | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Strength of ties in IPN | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Density of IPN | 0.10*** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Size of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | 0.41 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.92 |

| Strength IPN ties | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.05 | 0.14 | −0.31 | 0.23 |

| Density of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.70*** | 0.09 | −0.88 | −0.53 |

| Variables (dependent variables in italics in table) . | Path coefficient . | SE . | Boot BC CI . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL . | UL . | |||

| Professional identification | ||||

| Experience as a journalist | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Experience w/ current work arrangement | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Work location | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Working hours per week | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| Position | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.15 |

| Gender | −0.16*** | 0.04 | −0.25 | −0.08 |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Level of education | −0.08*** | 0.02 | −0.13 | −0.04 |

| Type of education | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Work arrangement | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.32 | 0.04 |

| Size of IPN | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Strength of ties in IPN | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Density of IPN | 0.10*** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Size of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | 0.41 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.92 |

| Strength IPN ties | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.05 | 0.14 | −0.31 | 0.23 |

| Density of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.70*** | 0.09 | −0.88 | −0.53 |

BC, bias-corrected; LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; W.A., work arrangement. Coefficients are rounded off to two decimals. *, **, and *** denote significance at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

| Variables (dependent variables in italics in table) . | Path coefficient . | SE . | Boot BC CI . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL . | UL . | |||

| Professional identification | ||||

| Experience as a journalist | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Experience w/ current work arrangement | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Work location | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Working hours per week | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| Position | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.15 |

| Gender | −0.16*** | 0.04 | −0.25 | −0.08 |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Level of education | −0.08*** | 0.02 | −0.13 | −0.04 |

| Type of education | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Work arrangement | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.32 | 0.04 |

| Size of IPN | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Strength of ties in IPN | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Density of IPN | 0.10*** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Size of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | 0.41 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.92 |

| Strength IPN ties | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.05 | 0.14 | −0.31 | 0.23 |

| Density of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.70*** | 0.09 | −0.88 | −0.53 |

| Variables (dependent variables in italics in table) . | Path coefficient . | SE . | Boot BC CI . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL . | UL . | |||

| Professional identification | ||||

| Experience as a journalist | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Experience w/ current work arrangement | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Work location | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| Working hours per week | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| Position | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.15 |

| Gender | −0.16*** | 0.04 | −0.25 | −0.08 |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Level of education | −0.08*** | 0.02 | −0.13 | −0.04 |

| Type of education | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Work arrangement | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.32 | 0.04 |

| Size of IPN | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Strength of ties in IPN | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Density of IPN | 0.10*** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Size of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | 0.41 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.92 |

| Strength IPN ties | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.05 | 0.14 | −0.31 | 0.23 |

| Density of IPN | ||||

| Work arrangement | −0.70*** | 0.09 | −0.88 | −0.53 |

BC, bias-corrected; LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; W.A., work arrangement. Coefficients are rounded off to two decimals. *, **, and *** denote significance at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

We see that the direct relationship between work arrangement and professional identification is negative, as expected, suggesting that freelancers identify less with their profession than their employed peers (b = −0.14). The relationship is not significant, however, and the empirical evidence does not support H1. That said, a post hoc analysis revealed a significant indirect relationship, as discussed below.

Next, among the second group of hypotheses, only H2C is supported by the empirical evidence, with a significant relationship between the respondents’ work arrangements and the density of their IPNs. As hypothesized, this relationship is negative (b = −0.70***), indicating that freelancers have less dense IPNs than their employed peers. The two remaining relationships that this group of hypotheses is concerned with vary in their sign (b = 0.41 and −0.05 for IPN size and IPN tie strength, respectively), but neither is significant.

Regarding the third set of hypotheses, a significant and positive relationship exists between an individual’s IPN density and professional identification (b = 0.10***), supporting H2C. However, H2A and H2B are not supported as there is not a significant relationship between the size of an individual’s IPN and their professional identification (b = 0.00), nor between the strength of their IPN ties and their professional identification (b = 0.02).

Among the control variables, only gender and level of education are significant (b = −0.16*** and −0.08***, respectively), both of which are negatively related to professional identification, indicating that men and highly educated workers identify less with their profession. Years of experience with current work arrangement, years of experience as a journalist, work location, job position, working hours per week, age, income, and type of education are not significantly related to professional identification in our sample.

Post hoc analysis

To analyse if and which aspects of an IPN mediate the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification, we conducted a post hoc analysis. This was done in Stata 17.0, but we explain the approach here. The only significant mediator was IPN density. Taking the product of the coefficients for the relationship between work arrangement and IPN density (b = −0.70***) and the relationship between IPN density and professional identification (b = 0.10***) gives us a coefficient for the indirect relationship of −0.07 (bootstrap standard error = 0.02, P = 0.002, CI = −0.11 to −0.02). This means that differences in freelancers’ and employees’ IPN density results in significant differences in their levels of professional identification; that is, freelancers identify less with their profession than employees because of their comparatively lower IPN density. Moreover, dividing the coefficient for this indirect relationship (b = −0.07**) by the coefficient for the total relationship between work arrangement and professional identification (b = −0.21, P = 0.018, CI = −0.11 to −0.02) informed us that IPN density mediates 33% of the relationship between work arrangement and professional identification.

DISCUSSION

As the world of professions continues to evolve, questions surrounding professionals’ identity and identification have become increasingly relevant. This study aims to advance our understanding of the factors that shape professionals’ identification with their profession. To do so, we have investigated the relationship between work arrangement, specifically freelancing and permanent employment, and professional identification and paid particular attention to if and how an IPN mediates this relationship.

Our results showed no direct relationship between work arrangement and professional identification, indicating at first sight that freelancers do not identify significantly more or less with their profession than permanent employees do as a consequence of their work arrangement. However, we did observe an indirect relationship. When accounting for the three aspects of their IPN, we found that because of their comparatively reduced IPN density, freelancers experience a significantly lower level of professional identification than permanent employees do. Viewed in combination, our results inform us that freelancers identify less with their profession than employees; however, this is only because of their comparatively reduced IPN density and not because they adhere to a different logic than employees. We structure the discussion of these results according to the order of the hypotheses, before discussing the results more combined.

Regarding the first hypothesis, the absence of a direct relationship between work arrangement and professional identification suggests the following. If freelancers do develop work identities of a more fluid and personalized form than what is the case for permanent employees, as several qualitative studies have argued (Cross and Swart 2021; Maestripieri 2019; Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski 2018), these unique work identities do not diverge markedly from the professional identity socially shared among professional peers. Freelancers, therefore, identify (almost as much) with the same professional identity as permanent employees. Following a similar vein of reasoning that informed our first hypothesis, we can think of several possible explanations for this result.

The first and most straightforward explanation is that adhering to a market logic is not detrimental to professional identification. Another possibility is that managerialism and a bureaucratic logic, that is, logics common in most organizations and known to conflict with professionalism (Abbott 1998; Noordegraaf 2015), could be equally as detrimental to professional identification as a market logic. Finally, it is possible that a market logic is detrimental to professional identification but that other factors accompanying freelancing may strengthen freelancers’ professional identification and counteract the detrimental influence of a market logic. For instance, freelancers tend to spend more time than employees on updating their professional knowledge (Barley and Kunda 2004; Osnowitz 2010). Given the epistemic foundation of professions, this time spent on furthering their professional knowledge, as well as the more comprehensive/updated professional knowledge in itself, could strengthen freelancers’ professional identification and mitigate the influence of a market logic.

In light of these explanations, our results challenge some of the theorization found in Maestripieri (2019) and Cross and Swart (2021). Maestripieri (2019) theorize that freelancers, because they adhere to a market logic, have different identity anchors than employees. More specifically, the extent to which freelancers view themselves as professionals is contingent on how successful they are in selling their services; in short, ‘[t]hey are what their clients need them to be’. (p. 367). However, our results indicate that freelancers’ professional identities are anchored equally as much by their work arrangement as the professional identities of permanent employees.

Arguing that freelancers are required to act as ‘chameleons’, as bricoleurs that use whatever they have at hand and adapt to their evolving circumstances, Cross and Swart (2021) develop the concept of ‘professional fluidity’. Professional fluidity is, according to Cross and Swart (2021), a dynamic strategy where ‘[i]ndividuals are defined not by their activities or who they are, but by their relations with others in the market’. (p. 1713). Put differently, their high level of professional fluidity entails that freelancers’ understanding of themselves as professionals, that is, their professional identities, vary according to the demands of their clients. Because their professional identities will then develop in different directions than the identity rooted in a professional community and socially shared by employed peers, freelancers’ professional identity becomes more personalized, and their level of identification with the socially shared professional identity decreases. Many freelancers undoubtedly have to act as chameleons at times; however, our results indicate that freelancers’ level of professional identification is robust to being a chameleon; that freelancers are not so professionally fluid that their professional identities and identification with this differ significantly from the socially shared professional identity and from permanent employees’ level of professional identification.

Regarding the relationship between work arrangement and IPN, our results inform us that freelancers have IPNs of equivalent size and strength to those of permanent employees. This suggests that life in the market enables freelancers to form lasting ties to their professional peers in a manner that matches permanent employees in terms of network strength. And vice versa. However, freelancers’ IPN density is lower than that of employees. Specifically, freelancers experience that they cannot rely on their professional peers for professional advice to the same extent as permanent employees experience they can. It therefore seems, as extant literature suggests (Barley and Kunda 2004; Osnowitz 2010), there is an ‘arm’s length’ distance between freelancing peers and freelancers and their employed peers. This result feeds into a broader set of literature that documents how nonstandard workers are alienated by permanent employees (e.g. Broschak, Davis-Blake and Block 2008).

The results show that IPN is related to professional identification, though density is the only relevant aspect of IPNs in this regard. This suggests that how close professional peers are to each other (quality), not how many professional peers they interact with (quantity), nor how often (frequency), is what drives professional identification. Interestingly, in their study of organizational identification, Jones and Volpe (2011) found that network size was the only significant predictor of identification among the IPN aspects studied here. While Jones and Volpe (2011) focused on a more extensive network than IPN and used a different measure of network density, a tentative inference can be made from these differences in results: Different network aspects matter for if and how workers identify with different targets at work, and one aspect may matter for one target but not for another. In the case of organizational identification, it is all about quantity, that is, how many employees a worker knows, while in the case of professional identification, it is more about quality, that is, how professionals are connected to their peers.

Finally, our post hoc analysis revealed that because of freelancers’ comparatively lower IPN density, freelancers identify less with their profession than employees. This outcome emphasizes the importance of an IPN as a driver for identity construction. In fact, viewed together, our results indicate that how freelancing shape IPNs is of greater importance to individuals’ professional identification than how freelancing impose a different set of logics compared to permanent employment. These results provide further credence to the theory developed by Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski (2018), which argues that freelancers’ lack of an organizational holding environment, that is, an organizational social context wherein they construct their identity, can be detrimental to their professional identification. At the same time, nuancing the theory developed by Petriglieri, Ashford and Wrzesniewski (2018), it is not the lack of professional peers that is detrimental to their professional identification but rather, according to our results, the distance between them and their peers.

Above, we asked the question: Is life in the job market less conducive to professional identification than life in the organization? Freelancers are sometimes portrayed as atomized workers that live out their work lives in solitude on the open market, a life marked by competition with professional peers, possibly reducing the relevance of belonging to a professional community. Our results suggest that freelancing and life in the market is less conducive to professional identification than permanent employment and life in the organization. Freelancers are more atomized, that is, have less dense IPNs, and therefore experience a lower level of identification with their profession. The remedy that immediately comes to mind is for professionals to be more inclusive towards freelancing peers as a proactive measure to increase their IPN density. Bolstering freelancers’ professional identification would serve to strengthen the professions’ foundations.

Limitations and future studies

This study, in itself and through its limitations, opens up for future studies. First, it relies on cross-sectional data; therefore, while the theory and model make causal assumptions, the data do not enable causal claims. This limitation particularly relates to the causal relationship between work arrangements and IPNs. It is possible that workers who fail to develop IPNs with high densities are the ones who end up freelancing, although theory and empirical studies would suggest that comparatively low network density follows somewhat naturally from (the competitive nature of) freelancing. While this study cannot make claims regarding the causal direction in the relationship between workers’ IPNs and their professional identification, McFarland and Pals (2005) found that causality flows primarily from social networks to identity. Nonetheless, longitudinal data would benefit future studies of the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification.

This study samples from what is viewed as a semi-profession. This could have implications for the generalizability of the findings. We argued in the introduction of this article that the benefits of sampling from journalists far outweigh any costs and that identity construction, following a neo-Institutional and discursive view on professions, is more dependent on how (semi-)professionals view themselves than how others (including us scholars) view them. Nonetheless, we encourage future studies to investigate further the relationship between work arrangements and professional identification. Such studies would also benefit from incorporating other nonstandard work forms, such as temporary employment and remote work.

A self-report questionnaire is the most favourable approach to investigate constructs such as professional identification (i.e. an internal/psychological construct) and different aspects of an IPN (e.g. the number of professional peers who are also friends) in a large sample. However, this approach can yield common method variance (CMV). In particular, factors such as scale format and item wording could introduce CMV in our study, and we, therefore, incorporated procedural remedies to reduce the relevance of these factors. Notably, the key variables all had different scale formats, which has been shown to mitigate CMV effectively (Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2012). We used simple, specific and concise questions, vetted the questionnaire with members of our population to eliminate ambiguity in the scale items, and used some items with reversed wording, all of which are important procedural remedies for CMV according to Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff (2012). It is also worth noting that CMV is of particular concern when respondents respond consistently across measures as a result of the measures easily lending themselves to implicit theories that the respondents are aware of (Morrison 2002; Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2012). We do not believe the respondents had any preconceived notions about the relationships between the variables in this study. Regardless, future studies would benefit from applying research designs with method- and data triangulation to further reduce the relevance of CMV.

Our operationalization of IPNs leaves room for future studies to further investigate how this social network relates to professional identification. Notably, we limit our measure of IPN size to close friends and ignore acquaintances. This creates a more reliable measure when using questionnaires as survey instruments; however, future studies could investigate through other means (e.g. an ethnographic approach) how acquaintances in IPNs relate to the formation of professional identities. Future studies could also include more complex and encompassing measures of the aspects characterizing IPNs to further nuance our understanding of IPNs’ functions in forming professional identities.

The nonsignificant direct relationship between work arrangement and professional identification challenges some of the theory in Cross and Swart (2021) and Maestripieri (2019). Following their vein of reasoning, we offer possible explanations for this nonsignificant relationship. Future studies could tease out if and which institutional logics promote or reduce professional identification. The work by Barbour and Lammers (2015), which incorporate insights from the literature on institutional logic to measure professional identity, could be a valuable source of inspiration when doing so.

In conclusion, the world of professions is evolving, opening up several venues for future studies. In this article, we show that the externalization of work from organizations is an essential factor to consider when discussing the future of professions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is very grateful to Torstein Nesheim and Karen Modesta Olsen for comments that were instrumental in producing this work. A big thanks is also due to Tatevik Harutyunyan and the STOP group at the Norwegian School of Economics for providing auxiliary registry data. Finally, the author would also like to thank an editor and two reviewers with the JPO, who provided extremely valuable feedback.

FUNDING

This research received funding from the Norwegian Research Council [project: 295764].

REFERENCES

——,

——, and

——,

——, and

—— (

—— (

—— and

—— (

—— and

——,