-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lorayne Caroline Resende, Mariana Michel Barbosa, Cristiane de Paula Rezende, Laís Lessa Neiva Pantuza, Edna Afonso Reis, Mariana Martins Gonzaga Nascimento, Instruments to measure patient satisfaction with comprehensive medication management (CMM) services: a scoping review, Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research, Volume 14, Issue 4, November 2023, Pages 370–382, https://doi.org/10.1093/jphsr/rmad044

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To map the instruments to measure patient satisfaction with comprehensive medication management (CMM) services and to compare them according to their development characteristics and applicability of patient-reported outcome measures (PRO) measures.

A scoping review was conducted using the methodology proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute and the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). Studies that developed or applied a patient satisfaction measurement instrument in CMM services, published from 1990 onwards were selected. The critical appraisal of the instruments identified was carried out using an 18 item checklist developed to systematically evaluate PRO measures.

A total of 28 studies were selected; in most (17), the applied instruments had been developed by the authors. Nine of them were validated, most of which used open-ended and closed questions in self-administered printed instruments. The best-qualified instrument reached 11 out of the 18 evaluated items, highlighting the difficulty in the definition of the satisfaction construct.

The review made it possible to identify the instruments available to measure patient satisfaction with CMM services and to comparatively highlight their characteristics and psychometric properties. It also pointed out the need to improve or develop a patient satisfaction instrument for CMM services. However, improvement is needed in many of the evaluated domains of the instruments to meet the desirable requirements for a PRO measure. These gaps should be taken into consideration in future research, aiming to build a robust and standardized instrument for the CMM service.

Introduction

Medications are essential for controlling diseases and increasing the population’s quality of life. However, if the medications are inappropriate for the patient, they can increase drug-related morbidity and mortality, consequently impacting individuals and healthcare systems [1]. In response to this social demand, in 1990, Hepler and Strand suggested the professional practice of pharmaceutical care [2]. This practice involves three components—philosophy of practice, patient care process, and a practice management system—and is materialized in society through the comprehensive medication management (CMM) service [3, 4].

The pharmaceutical care philosophy defines that the pharmacist assumes responsibility for the pharmacotherapeutic needs of patients by trying to identify, prevent, and solve so-called drug therapy problems (DTPs), within a line of care centred on the patient and based on building a therapeutic relationship [3, 4]. In this perspective, the patients should be considered as people with knowledge, experience, and values. As a result, they should be integrated as a health team member, participate in health-related decisions, and assume leadership with regard to their pharmacotherapy [3, 4].

The pharmacist evaluates each medication based on its indication, effectiveness, safety, and convenience during the care process. If any DTPs are identified, the pharmacist proposes interventions for resolving them collaboratively with the patient and with other members of the care team. After this stage, the pharmacist monitors the outcomes of the interventions in a longitudinal follow-up process [3, 4]. CMM provision is made possible through a practice management system that lists the resources required, such as a system for recording care, documentation, care infrastructure, human resources, and payment for the service, among others [3, 4].

The CMM service also requires ongoing quality evaluation and monitoring. Following this perspective, Lima et al. [5] developed and validated a set of key performance indicators for the CMM service for outpatients. Among them, there is patient satisfaction. Furthermore, assessing patient satisfaction can clarify the value of pharmaceutical care services in enhancing patient experience with health systems [6].

Although there is no consensus in the literature regarding the concept of patient satisfaction, it can be understood as a multidimensional construct that qualifies the health service offered and assesses the expectations and needs of patients [7]. Gill and White [8] explain this concept through some theories that consider satisfaction as: convergence of the patient’s health guidelines and the provider conditions [9]; consequence of positive individual evaluations of different dimensions of health care [10]; the patient’s personal preferences and expectations [11]; socially mediated expectations reflected in patient health goals [12]; and the primary outcome of the interpersonal care process [13].

The patient satisfaction measure, considered a patient-reported outcome (PRO), represents a relevant humanistic result of patient-centred services [14]. Despite this, there are few instruments available in the literature to evaluate patient satisfaction with the CMM service, making it difficult to compare services for this parameter [15]. Given this context, it becomes relevant to identify the instruments available to assess the satisfaction of patients followed up in CMM services, and the scoping review is an adequate tool for this.

Considering this, the authors of this review carried out a previous search in the Medline and Cochrane databases in May 2021 and did not find any review on the subject. This fact led to a scoping review to map and analyse available instruments for measuring patient satisfaction observed in CMM services. More specifically, this review aims to answer the following questions: what satisfaction measurement instruments are available for patients seen in CMM services? What are the characteristics of the instruments concerning reliability, validity, and responsiveness?

Methods

This scoping review followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews [16] (Appendix 1) and the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis [17]. The review protocol was previously published [18] and registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform (10.17605/OSF.IO/RZA38).

Search strategy and formulation of the research question

A search strategy was prepared [17], with the aim of identifying studies that answer the following question: what satisfaction measurement instruments are available for patients followed up in CMM services?

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), EMBASE, Cochrane, Scopus, CINAHL, and Web of Science. The electronic search strategy for each database was carried out as shown in Appendix 2. The search strategy combined text words and indexed terms related to pharmaceutical services and patient satisfaction, and was validated using the Epistemonikos database and Google Scholar® (more details on how the validation of the terms was performed in Resende et al. [18]).

A search in the gray literature was also conducted in two Brazilian electronic databases of theses and dissertations (Brazilian Catalog of Theses and Dissertations and Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations). A manual search was performed in the references of the included studies and in the journal with the highest number of published studies retrieved by the initial search strategy.

Study screening and selection

Mendeley® software was used to identify and exclude duplicates. The selection of studies was performed on the Rayyan® platform [19] by a pair of independent reviewers (LCR; CR) in two steps: (i) titles and abstracts screening; and (ii) full-text reading of the studies selected in the previous phase. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (MMGN). Exclusions in the last phase of study selection were documented.

Considering the PCC (participants, concept, and context) strategy suggested for scoping reviews, the adopted inclusion criteria were: (i) participants: patients who are aged 18 or older, or their caregivers, followed in a CMM service [4]; (ii) concept: instruments to measure patient satisfaction with CMM services, both studies that developed/outlined an instrument to assess patient satisfaction and studies that applied (validated) these instruments in clinical practice were included; (iii) context: any clinical practice settings; (iv) study type: methodological studies for the development of instruments to measure patient satisfaction and qualitative, experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational studies in which patient satisfaction was evaluated using an instrument; and (v) publication date: studies published from the year 1990 (the year in which the pharmaceutical care practice was proposed by Hepler and Strand) [2]. There were no language restrictions.

In this review, the following definition for the CMM service was adopted:

(…) the standard of care that ensures that each patient’s medications (whether prescribed, nonprescription, alternative, traditional, vitamins, or nutritional supplements) are individually evaluated to determine whether each is appropriate for the patient, effective for the health condition, safe for comorbidities and other medications in use, and which can be taken by the patient as intended. The CMM includes an individualized care plan that achieves the intended goals of therapy with appropriate follow-up to determine actual patient outcomes. All of this occurs because the patient understands, agrees to, and actively participates in the treatment regimen [4]. (p. 5).

The exclusion criteria were: (i) type of publication: book chapters, letters, editorials, notes, and abstracts with insufficient information for eligibility analysis; (ii) study type: reviews and study protocol; (iii) type of participants: studies carried out to identify satisfaction from the point of view of health professionals; and (iv) type of pharmaceutical service: medication reconciliation, transition of care, disease state management, medication review, guidance on correct medication use, pharmaceutical education, health condition screening, or dispensing services. Studies and instruments not publicly available were requested from their authors. Those which were not made available even after request were excluded from the evaluation.

Data charting, synthesis of results, and comparative analysis of the instruments

Data extraction and evaluation of the instruments were performed by two independent reviewers. All disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers. The data extraction methodology was validated using two studies that met the inclusion criteria.

The following information was extracted using a spreadsheet in Excel: authors; year of publication; country; objective; definition of the CMM service; and validation characteristics. For all the original instruments (validated by the authors of the studies), other characteristics were extracted: mode of administration (self-applied, by the service provider, or by third-party interview); format of administration (printed or digital); type of questions (Likert scale, open-ended or dichotomic), and number of items.

All the original instruments were evaluated using a checklist developed by Francis et al. [14] to evaluate PRO measures and to identify their strengths, weaknesses, and applicability. It is suitable for carefully measuring satisfaction with health care services and includes practical aspects of instrument administration [14]. The checklist was developed based on six fundamental attributes [14]: (1) conceptual model, in which the instrument must clearly define the construct to be measured and the target population; (2) content validity, where evidence is sought that the PRO measure is adequate for its intended use, generally using interviews with the target audience to assess the clarity of the questions and concepts addressed; (3) reliability, where the degree to which the scores are free of random errors was evaluated, through the analysis of internal consistency or test–retest; (4) construct validity, where it is evaluated whether the test measures the proposed theoretical concept and possible inferences through factor analysis or measures of responsiveness to change, when applicable; (5) scoring and interpretation, which evaluates the instrument’s scoring system and the clarity with which the author explains the meaning of the score obtained; (6) respondent burden and presentation, which refers to the time and effort required from the respondent or those administering the PRO measurement instrument, including the literacy level required to understand the questions raised.

For each attribute addressed, the checklist presents several questions that are scored a zero or one point according to the absence or presence of the criterion. Therefore, the checklist score ranges from 0 to 18 points, in which the higher the score the better the instrument. The maximum value, in turn, corresponds to the fulfillment of all the desirable requirements for a PRO measure. It is important to point out that this instrument does not present stratification of the scores [14].

Results

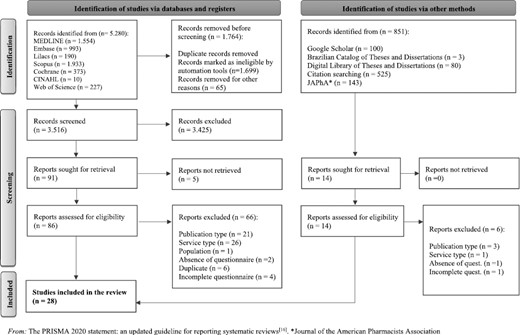

A total of 5280 studies were retrieved by searching the selected databases. After excluding 1764 duplicates, 3516 titles and abstracts were evaluated. A total of 91 studies were selected for full-text reading but five of them could not be retrieved. Therefore, 86 studies were evaluated for eligibility and 20 of them met the inclusion criteria. The search in gray literature and a manual search retrieved 14 additional studies, eight of which were eligible. In total, 28 studies were included (Fig. 1). Agreement between reviewers was assessed and reached 95.9% with a Kappa index of 0.872, which demonstrated a very good agreement strength [20].

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the 28 included studies [15, 21–47]. A high number of studies (n = 12; 42.9%) were conducted in North America [15, 21, 23–25, 27, 41–45, 47], with 10 of these (35.7%) [15, 21, 23, 25, 27, 41–44, 47] developed in the USA. The publication year of the studies ranged from 1998 [23] to 2022 [47] with the majority (57.1%; n = 16) [15, 21, 27, 28, 31, 32, 35–39, 41–44, 46] concentrated between 2010 to 2019. Six different terms for the definition of the service offered were used, highlighting the term “Pharmaceutical Care”, presented in 15 studies (53.6%) [21, 23–26, 28, 30–35, 37, 40, 45].

| Author (year) . | Country . | Instrument name—abbreviation . | Objective . | Context . | Term used for service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development and validation studies of a patient satisfaction measurement instrument | |||||

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Spain | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | To develop and validate an instrument to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services | Adult patients or caregivers from community pharmacies who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Armando, Uema and Solá [22] (2005) | Argentina | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacotherapy follow-up | Adult patients or caregivers who received the service at the College of Pharmacists of the Province of Cordoba | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | EUA | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | To evaluate the humanistic outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service | Adult patients with hypertension or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kassam, Collins and Berkowitz [24] (2009) | Canada | Satisfaction survey | To evaluate the patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services. | Asthma patients who received the service at community pharmacies | Pharmaceutical care |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | EUA | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | To develop a questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care and to establish its dimensional structure | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2005) | Brazil | Undefined | To define a socio-demographic profile of a group of older patients to implement pharmaceutical care; to analyse the outcomes of pharmacist interventions; and to assess patient satisfaction | Older patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To measure patient satisfaction with a telephone medication therapy management program | Adult patients who received telephone service consultation provided by Scott & White Health Plan part D. | medication therapy management |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Spain | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | To design and validate a questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care | Outpatients from five hospitals who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To develop a psychometrically valid questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with comprehensive medication management services | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for intergrade medication management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

| Translation and validation studies | |||||

| Correr et al. [29] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To translate and validate the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25] into Brazilian Portuguese | Adult patients with type 2 diabetes, clinical trial participants from Federal University of Paraná, Brazil | Pharmaceutical services |

| Iglésias et al. [30] (2005) | Portugal | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário sobre os Serviços da Farmácia) | To obtain one validated instrument in Portuguese (European) from the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kanovsky et al. [31] (2017) | Slovak Republic | Undefined | To perform a robust validation of a patient satisfaction instrument previously developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Customers from community pharmacies in Slovak who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Quispe et al. [32] (2011) | Spain | Patient satisfaction questionnaire—PSQ | To carry out a cross-cultural adaptation, to describe and assess the psychometric properties of a patient satisfaction questionnaire developed by Traverso et al [55]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies in Spain who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Studies that applied a previously validated instrument to measure satisfaction | |||||

| Andrade et al. [33] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To evaluate patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service provided in a private community pharmacy using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients from a private communitarian pharmacy who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dantas [34] (2007) | Brazil | Undefined | To describe the humanistic and clinical outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] to measure patient satisfaction | Asthma patients who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dewulf [35] (2010) | Brazil | Undefined | To assess the contribution of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] | Adult patients with inflammatory bowel diseases who received the service at a reference hospital | Pharmaceutical care |

| Foppa [36] (2014) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To identify the managerial, humanistic, and clinical elements necessary to qualify a clinical pharmaceutical service using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients with Parkinson’s disease or caregivers who received the service | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Penaforte [37] (2011) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To implement a pharmaceutical care model, evaluating its clinical, economic and social impact using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29]. | Adult patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Reis [38] (2018) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To analyse the clinical and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services using the instrument developed by Correr et al [29] | Renal transplant patients who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Non-validated informal measurements of patient satisfaction | |||||

| Garcia-Cardenas et al. [39] (2017) | Spain | Undefined | To describe the implementation process of a medication review service with follow-up provided in a community pharmacy setting and to evaluate its outcomes | Adult patients from community pharmacies who received the service | Medication review with follow-up |

| Hasen and Negeso [40] (2021) | Ethiopia | Undefined | To determine patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service and associated factors | Adult patients admitted to medical wards in Jimma University Medical Centre who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kim et al. [41] (2016) | EUA | Survey instrument | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacists and pharmacy services | Adult patients who received the service at the University Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences | Medication therapy management |

| Lam [42] (2011) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To describe medication therapy management services via videoconference | Adult patients with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease who received the service via videoconference | Medication therapy management |

| Parsons and Zimmermann [43] (2019) | EUA | Satisfaction survey | To describe and evaluate a novel practice setting for pharmacists within an occupational health clinic, and to evaluate the impact on patient care | Adult patients with any chronic disease, elevate biometric results or medication questions who received the service at an occupational health clinic of a large company | Comprehensive medication management |

| Ramalho de Oliveira et al. [44] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To present the clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services | Adult patients eligible for medication therapy management services in a health care delivery system over 10 years | Medication therapy management |

| Volume et al. [45] (2001) | Canada | Undefined | To describe changes in patients’ adherence to therapy, expectations and satisfaction with pharmacy services, and health-related quality of life after the provision of pharmaceutical care | Older patients use three or more medications covered under Alberta Health & Wellness’s senior drug benefit plan | Pharmaceutical care |

| Yeoh et al. [46] (2013) | Singapore | Patient satisfaction survey—PSS | To identify common drug-related problems among older cancer patients; to determine the effectiveness of Medication Therapy Management services, the clinical significance of pharmacist interventions, and patient satisfaction | Elderly cancer patients with at least one chronic medication who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Psychometric evaluation study of a previously validated instrument | |||||

| Campbell et al. [47] (2022) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To assess the psychometric properties and factor structure of the instrument developed by Moon et al. [15]. | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for Intergrade Medication Management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

| Author (year) . | Country . | Instrument name—abbreviation . | Objective . | Context . | Term used for service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development and validation studies of a patient satisfaction measurement instrument | |||||

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Spain | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | To develop and validate an instrument to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services | Adult patients or caregivers from community pharmacies who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Armando, Uema and Solá [22] (2005) | Argentina | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacotherapy follow-up | Adult patients or caregivers who received the service at the College of Pharmacists of the Province of Cordoba | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | EUA | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | To evaluate the humanistic outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service | Adult patients with hypertension or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kassam, Collins and Berkowitz [24] (2009) | Canada | Satisfaction survey | To evaluate the patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services. | Asthma patients who received the service at community pharmacies | Pharmaceutical care |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | EUA | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | To develop a questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care and to establish its dimensional structure | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2005) | Brazil | Undefined | To define a socio-demographic profile of a group of older patients to implement pharmaceutical care; to analyse the outcomes of pharmacist interventions; and to assess patient satisfaction | Older patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To measure patient satisfaction with a telephone medication therapy management program | Adult patients who received telephone service consultation provided by Scott & White Health Plan part D. | medication therapy management |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Spain | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | To design and validate a questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care | Outpatients from five hospitals who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To develop a psychometrically valid questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with comprehensive medication management services | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for intergrade medication management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

| Translation and validation studies | |||||

| Correr et al. [29] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To translate and validate the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25] into Brazilian Portuguese | Adult patients with type 2 diabetes, clinical trial participants from Federal University of Paraná, Brazil | Pharmaceutical services |

| Iglésias et al. [30] (2005) | Portugal | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário sobre os Serviços da Farmácia) | To obtain one validated instrument in Portuguese (European) from the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kanovsky et al. [31] (2017) | Slovak Republic | Undefined | To perform a robust validation of a patient satisfaction instrument previously developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Customers from community pharmacies in Slovak who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Quispe et al. [32] (2011) | Spain | Patient satisfaction questionnaire—PSQ | To carry out a cross-cultural adaptation, to describe and assess the psychometric properties of a patient satisfaction questionnaire developed by Traverso et al [55]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies in Spain who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Studies that applied a previously validated instrument to measure satisfaction | |||||

| Andrade et al. [33] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To evaluate patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service provided in a private community pharmacy using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients from a private communitarian pharmacy who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dantas [34] (2007) | Brazil | Undefined | To describe the humanistic and clinical outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] to measure patient satisfaction | Asthma patients who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dewulf [35] (2010) | Brazil | Undefined | To assess the contribution of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] | Adult patients with inflammatory bowel diseases who received the service at a reference hospital | Pharmaceutical care |

| Foppa [36] (2014) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To identify the managerial, humanistic, and clinical elements necessary to qualify a clinical pharmaceutical service using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients with Parkinson’s disease or caregivers who received the service | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Penaforte [37] (2011) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To implement a pharmaceutical care model, evaluating its clinical, economic and social impact using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29]. | Adult patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Reis [38] (2018) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To analyse the clinical and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services using the instrument developed by Correr et al [29] | Renal transplant patients who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Non-validated informal measurements of patient satisfaction | |||||

| Garcia-Cardenas et al. [39] (2017) | Spain | Undefined | To describe the implementation process of a medication review service with follow-up provided in a community pharmacy setting and to evaluate its outcomes | Adult patients from community pharmacies who received the service | Medication review with follow-up |

| Hasen and Negeso [40] (2021) | Ethiopia | Undefined | To determine patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service and associated factors | Adult patients admitted to medical wards in Jimma University Medical Centre who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kim et al. [41] (2016) | EUA | Survey instrument | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacists and pharmacy services | Adult patients who received the service at the University Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences | Medication therapy management |

| Lam [42] (2011) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To describe medication therapy management services via videoconference | Adult patients with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease who received the service via videoconference | Medication therapy management |

| Parsons and Zimmermann [43] (2019) | EUA | Satisfaction survey | To describe and evaluate a novel practice setting for pharmacists within an occupational health clinic, and to evaluate the impact on patient care | Adult patients with any chronic disease, elevate biometric results or medication questions who received the service at an occupational health clinic of a large company | Comprehensive medication management |

| Ramalho de Oliveira et al. [44] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To present the clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services | Adult patients eligible for medication therapy management services in a health care delivery system over 10 years | Medication therapy management |

| Volume et al. [45] (2001) | Canada | Undefined | To describe changes in patients’ adherence to therapy, expectations and satisfaction with pharmacy services, and health-related quality of life after the provision of pharmaceutical care | Older patients use three or more medications covered under Alberta Health & Wellness’s senior drug benefit plan | Pharmaceutical care |

| Yeoh et al. [46] (2013) | Singapore | Patient satisfaction survey—PSS | To identify common drug-related problems among older cancer patients; to determine the effectiveness of Medication Therapy Management services, the clinical significance of pharmacist interventions, and patient satisfaction | Elderly cancer patients with at least one chronic medication who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Psychometric evaluation study of a previously validated instrument | |||||

| Campbell et al. [47] (2022) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To assess the psychometric properties and factor structure of the instrument developed by Moon et al. [15]. | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for Intergrade Medication Management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

| Author (year) . | Country . | Instrument name—abbreviation . | Objective . | Context . | Term used for service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development and validation studies of a patient satisfaction measurement instrument | |||||

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Spain | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | To develop and validate an instrument to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services | Adult patients or caregivers from community pharmacies who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Armando, Uema and Solá [22] (2005) | Argentina | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacotherapy follow-up | Adult patients or caregivers who received the service at the College of Pharmacists of the Province of Cordoba | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | EUA | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | To evaluate the humanistic outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service | Adult patients with hypertension or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kassam, Collins and Berkowitz [24] (2009) | Canada | Satisfaction survey | To evaluate the patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services. | Asthma patients who received the service at community pharmacies | Pharmaceutical care |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | EUA | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | To develop a questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care and to establish its dimensional structure | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2005) | Brazil | Undefined | To define a socio-demographic profile of a group of older patients to implement pharmaceutical care; to analyse the outcomes of pharmacist interventions; and to assess patient satisfaction | Older patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To measure patient satisfaction with a telephone medication therapy management program | Adult patients who received telephone service consultation provided by Scott & White Health Plan part D. | medication therapy management |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Spain | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | To design and validate a questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care | Outpatients from five hospitals who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To develop a psychometrically valid questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with comprehensive medication management services | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for intergrade medication management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

| Translation and validation studies | |||||

| Correr et al. [29] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To translate and validate the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25] into Brazilian Portuguese | Adult patients with type 2 diabetes, clinical trial participants from Federal University of Paraná, Brazil | Pharmaceutical services |

| Iglésias et al. [30] (2005) | Portugal | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário sobre os Serviços da Farmácia) | To obtain one validated instrument in Portuguese (European) from the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kanovsky et al. [31] (2017) | Slovak Republic | Undefined | To perform a robust validation of a patient satisfaction instrument previously developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Customers from community pharmacies in Slovak who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Quispe et al. [32] (2011) | Spain | Patient satisfaction questionnaire—PSQ | To carry out a cross-cultural adaptation, to describe and assess the psychometric properties of a patient satisfaction questionnaire developed by Traverso et al [55]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies in Spain who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Studies that applied a previously validated instrument to measure satisfaction | |||||

| Andrade et al. [33] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To evaluate patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service provided in a private community pharmacy using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients from a private communitarian pharmacy who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dantas [34] (2007) | Brazil | Undefined | To describe the humanistic and clinical outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] to measure patient satisfaction | Asthma patients who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dewulf [35] (2010) | Brazil | Undefined | To assess the contribution of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] | Adult patients with inflammatory bowel diseases who received the service at a reference hospital | Pharmaceutical care |

| Foppa [36] (2014) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To identify the managerial, humanistic, and clinical elements necessary to qualify a clinical pharmaceutical service using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients with Parkinson’s disease or caregivers who received the service | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Penaforte [37] (2011) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To implement a pharmaceutical care model, evaluating its clinical, economic and social impact using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29]. | Adult patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Reis [38] (2018) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To analyse the clinical and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services using the instrument developed by Correr et al [29] | Renal transplant patients who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Non-validated informal measurements of patient satisfaction | |||||

| Garcia-Cardenas et al. [39] (2017) | Spain | Undefined | To describe the implementation process of a medication review service with follow-up provided in a community pharmacy setting and to evaluate its outcomes | Adult patients from community pharmacies who received the service | Medication review with follow-up |

| Hasen and Negeso [40] (2021) | Ethiopia | Undefined | To determine patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service and associated factors | Adult patients admitted to medical wards in Jimma University Medical Centre who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kim et al. [41] (2016) | EUA | Survey instrument | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacists and pharmacy services | Adult patients who received the service at the University Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences | Medication therapy management |

| Lam [42] (2011) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To describe medication therapy management services via videoconference | Adult patients with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease who received the service via videoconference | Medication therapy management |

| Parsons and Zimmermann [43] (2019) | EUA | Satisfaction survey | To describe and evaluate a novel practice setting for pharmacists within an occupational health clinic, and to evaluate the impact on patient care | Adult patients with any chronic disease, elevate biometric results or medication questions who received the service at an occupational health clinic of a large company | Comprehensive medication management |

| Ramalho de Oliveira et al. [44] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To present the clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services | Adult patients eligible for medication therapy management services in a health care delivery system over 10 years | Medication therapy management |

| Volume et al. [45] (2001) | Canada | Undefined | To describe changes in patients’ adherence to therapy, expectations and satisfaction with pharmacy services, and health-related quality of life after the provision of pharmaceutical care | Older patients use three or more medications covered under Alberta Health & Wellness’s senior drug benefit plan | Pharmaceutical care |

| Yeoh et al. [46] (2013) | Singapore | Patient satisfaction survey—PSS | To identify common drug-related problems among older cancer patients; to determine the effectiveness of Medication Therapy Management services, the clinical significance of pharmacist interventions, and patient satisfaction | Elderly cancer patients with at least one chronic medication who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Psychometric evaluation study of a previously validated instrument | |||||

| Campbell et al. [47] (2022) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To assess the psychometric properties and factor structure of the instrument developed by Moon et al. [15]. | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for Intergrade Medication Management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

| Author (year) . | Country . | Instrument name—abbreviation . | Objective . | Context . | Term used for service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development and validation studies of a patient satisfaction measurement instrument | |||||

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Spain | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | To develop and validate an instrument to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services | Adult patients or caregivers from community pharmacies who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Armando, Uema and Solá [22] (2005) | Argentina | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacotherapy follow-up | Adult patients or caregivers who received the service at the College of Pharmacists of the Province of Cordoba | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | EUA | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | To evaluate the humanistic outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service | Adult patients with hypertension or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kassam, Collins and Berkowitz [24] (2009) | Canada | Satisfaction survey | To evaluate the patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care services. | Asthma patients who received the service at community pharmacies | Pharmaceutical care |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | EUA | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | To develop a questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care and to establish its dimensional structure | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2005) | Brazil | Undefined | To define a socio-demographic profile of a group of older patients to implement pharmaceutical care; to analyse the outcomes of pharmacist interventions; and to assess patient satisfaction | Older patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To measure patient satisfaction with a telephone medication therapy management program | Adult patients who received telephone service consultation provided by Scott & White Health Plan part D. | medication therapy management |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Spain | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | To design and validate a questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical care | Outpatients from five hospitals who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To develop a psychometrically valid questionnaire for measuring patient satisfaction with comprehensive medication management services | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for intergrade medication management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

| Translation and validation studies | |||||

| Correr et al. [29] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To translate and validate the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25] into Brazilian Portuguese | Adult patients with type 2 diabetes, clinical trial participants from Federal University of Paraná, Brazil | Pharmaceutical services |

| Iglésias et al. [30] (2005) | Portugal | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário sobre os Serviços da Farmácia) | To obtain one validated instrument in Portuguese (European) from the instrument developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kanovsky et al. [31] (2017) | Slovak Republic | Undefined | To perform a robust validation of a patient satisfaction instrument previously developed by Larson et al. [25]. | Customers from community pharmacies in Slovak who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Quispe et al. [32] (2011) | Spain | Patient satisfaction questionnaire—PSQ | To carry out a cross-cultural adaptation, to describe and assess the psychometric properties of a patient satisfaction questionnaire developed by Traverso et al [55]. | Adult patients from community pharmacies in Spain who did not receive the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Studies that applied a previously validated instrument to measure satisfaction | |||||

| Andrade et al. [33] (2009) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To evaluate patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service provided in a private community pharmacy using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients from a private communitarian pharmacy who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dantas [34] (2007) | Brazil | Undefined | To describe the humanistic and clinical outcomes of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] to measure patient satisfaction | Asthma patients who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Dewulf [35] (2010) | Brazil | Undefined | To assess the contribution of a pharmaceutical care service using the instrument developed by Lyra Júnior et al. [26] | Adult patients with inflammatory bowel diseases who received the service at a reference hospital | Pharmaceutical care |

| Foppa [36] (2014) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To identify the managerial, humanistic, and clinical elements necessary to qualify a clinical pharmaceutical service using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29] | Adult patients with Parkinson’s disease or caregivers who received the service | Pharmacotherapy follow-up |

| Penaforte [37] (2011) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To implement a pharmaceutical care model, evaluating its clinical, economic and social impact using the instrument developed by Correr et al. [29]. | Adult patients with hypertension who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Reis [38] (2018) | Brazil | Pharmacy services questionnaire (Questionário de Satisfação com Serviços da Farmácia - QSSF) | To analyse the clinical and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services using the instrument developed by Correr et al [29] | Renal transplant patients who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Non-validated informal measurements of patient satisfaction | |||||

| Garcia-Cardenas et al. [39] (2017) | Spain | Undefined | To describe the implementation process of a medication review service with follow-up provided in a community pharmacy setting and to evaluate its outcomes | Adult patients from community pharmacies who received the service | Medication review with follow-up |

| Hasen and Negeso [40] (2021) | Ethiopia | Undefined | To determine patient satisfaction with a pharmaceutical care service and associated factors | Adult patients admitted to medical wards in Jimma University Medical Centre who received the service | Pharmaceutical care |

| Kim et al. [41] (2016) | EUA | Survey instrument | To assess patient satisfaction with pharmacists and pharmacy services | Adult patients who received the service at the University Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences | Medication therapy management |

| Lam [42] (2011) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To describe medication therapy management services via videoconference | Adult patients with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease who received the service via videoconference | Medication therapy management |

| Parsons and Zimmermann [43] (2019) | EUA | Satisfaction survey | To describe and evaluate a novel practice setting for pharmacists within an occupational health clinic, and to evaluate the impact on patient care | Adult patients with any chronic disease, elevate biometric results or medication questions who received the service at an occupational health clinic of a large company | Comprehensive medication management |

| Ramalho de Oliveira et al. [44] (2010) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To present the clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes of medication therapy management services | Adult patients eligible for medication therapy management services in a health care delivery system over 10 years | Medication therapy management |

| Volume et al. [45] (2001) | Canada | Undefined | To describe changes in patients’ adherence to therapy, expectations and satisfaction with pharmacy services, and health-related quality of life after the provision of pharmaceutical care | Older patients use three or more medications covered under Alberta Health & Wellness’s senior drug benefit plan | Pharmaceutical care |

| Yeoh et al. [46] (2013) | Singapore | Patient satisfaction survey—PSS | To identify common drug-related problems among older cancer patients; to determine the effectiveness of Medication Therapy Management services, the clinical significance of pharmacist interventions, and patient satisfaction | Elderly cancer patients with at least one chronic medication who received the service | Medication therapy management |

| Psychometric evaluation study of a previously validated instrument | |||||

| Campbell et al. [47] (2022) | EUA | Patient satisfaction survey | To assess the psychometric properties and factor structure of the instrument developed by Moon et al. [15]. | Adult patients from the health-systems alliance for Intergrade Medication Management who received the service | Comprehensive medication management |

Instrument characteristics and evaluation score on the Francis checklist

Among the 28 selected studies, nine (32.1%) [15, 21–28] used original and validated instruments. The characteristics of these studies that used an original and validated instrument are described in Table 2. It is noteworthy that most studies (n = 17; 60.7%) [15, 21–25, 27, 28, 39–47], used instruments developed by the authors themselves, and 11 (39.3%) [29–38, 47] used instruments developed by other authors or their translation and adaptation.

Characteristics of the original validated instruments to measure patient satisfaction with CMM services.

| Author (year) . | Name of instrument—abbreviations . | Language . | Construct definition . | How is the administration? . | Type of questions (number of questions) . | Number of respondents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a reflection of the provider’s ability to meet the needs of patients | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 103 |

| Armandoet al. [22] (2005) | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a humanistic outcome of approving quality of care and reflects the provider’s ability to meet patients’ needs | Self-administered printed instrument | dichotomic (6)*; Likert-scale 1–4 (5); open-ended (1) | 40 |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | English | Undefined | Instrument administered by interviewer** | Likert-scale 1–5 (17) | 227 |

| Kassamet al. [24] (2009) | Satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15) | 147 |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | English | Patient satisfaction can be seen as a personal assessment of health care services and providers who reflect the reality of care, as well as the patient’s preferences and expectations, and can be conceptualized as an assessment of the pharmacist’s performance in patient care. | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (20) | 428 |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2004) | Undefined | Portuguese | Patient satisfaction is defined as an outcome which reflects the degree of involvement of the pharmacist in the care process as well as the needs and expectations of the patient | Printed instrument administered by an interviewer | Likert-scale 1–5 (14); open-ended (2) | 30 |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15); open-ended (3) | 47 |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | Spanish | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 154 |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–4 (9); open-ended (1) | 195 |

| Author (year) . | Name of instrument—abbreviations . | Language . | Construct definition . | How is the administration? . | Type of questions (number of questions) . | Number of respondents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a reflection of the provider’s ability to meet the needs of patients | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 103 |

| Armandoet al. [22] (2005) | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a humanistic outcome of approving quality of care and reflects the provider’s ability to meet patients’ needs | Self-administered printed instrument | dichotomic (6)*; Likert-scale 1–4 (5); open-ended (1) | 40 |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | English | Undefined | Instrument administered by interviewer** | Likert-scale 1–5 (17) | 227 |

| Kassamet al. [24] (2009) | Satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15) | 147 |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | English | Patient satisfaction can be seen as a personal assessment of health care services and providers who reflect the reality of care, as well as the patient’s preferences and expectations, and can be conceptualized as an assessment of the pharmacist’s performance in patient care. | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (20) | 428 |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2004) | Undefined | Portuguese | Patient satisfaction is defined as an outcome which reflects the degree of involvement of the pharmacist in the care process as well as the needs and expectations of the patient | Printed instrument administered by an interviewer | Likert-scale 1–5 (14); open-ended (2) | 30 |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15); open-ended (3) | 47 |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | Spanish | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 154 |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–4 (9); open-ended (1) | 195 |

*Dichotomic = yes or no questions.

**The instrument was applied by a third partial and the format (printed or digital) was not described by the authors.

Characteristics of the original validated instruments to measure patient satisfaction with CMM services.

| Author (year) . | Name of instrument—abbreviations . | Language . | Construct definition . | How is the administration? . | Type of questions (number of questions) . | Number of respondents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a reflection of the provider’s ability to meet the needs of patients | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 103 |

| Armandoet al. [22] (2005) | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a humanistic outcome of approving quality of care and reflects the provider’s ability to meet patients’ needs | Self-administered printed instrument | dichotomic (6)*; Likert-scale 1–4 (5); open-ended (1) | 40 |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | English | Undefined | Instrument administered by interviewer** | Likert-scale 1–5 (17) | 227 |

| Kassamet al. [24] (2009) | Satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15) | 147 |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | English | Patient satisfaction can be seen as a personal assessment of health care services and providers who reflect the reality of care, as well as the patient’s preferences and expectations, and can be conceptualized as an assessment of the pharmacist’s performance in patient care. | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (20) | 428 |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2004) | Undefined | Portuguese | Patient satisfaction is defined as an outcome which reflects the degree of involvement of the pharmacist in the care process as well as the needs and expectations of the patient | Printed instrument administered by an interviewer | Likert-scale 1–5 (14); open-ended (2) | 30 |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15); open-ended (3) | 47 |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | Spanish | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 154 |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–4 (9); open-ended (1) | 195 |

| Author (year) . | Name of instrument—abbreviations . | Language . | Construct definition . | How is the administration? . | Type of questions (number of questions) . | Number of respondents . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] (2012) | Patient satisfaction survey (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a reflection of the provider’s ability to meet the needs of patients | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 103 |

| Armandoet al. [22] (2005) | Patient satisfaction survey under pharmacotherapy follow-up (Cuestionario de satisfacción de pacientes bajo Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico) | Spanish | Satisfaction is defined as a humanistic outcome of approving quality of care and reflects the provider’s ability to meet patients’ needs | Self-administered printed instrument | dichotomic (6)*; Likert-scale 1–4 (5); open-ended (1) | 40 |

| Gourley et al. [23] (1998) | Pharmaceutical care questionnaire—PCQ | English | Undefined | Instrument administered by interviewer** | Likert-scale 1–5 (17) | 227 |

| Kassamet al. [24] (2009) | Satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15) | 147 |

| Larson et al. [25] (2002) | Pharmacy services questionnaire—PSQ | English | Patient satisfaction can be seen as a personal assessment of health care services and providers who reflect the reality of care, as well as the patient’s preferences and expectations, and can be conceptualized as an assessment of the pharmacist’s performance in patient care. | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (20) | 428 |

| Lyra Júnior et al. [26] (2004) | Undefined | Portuguese | Patient satisfaction is defined as an outcome which reflects the degree of involvement of the pharmacist in the care process as well as the needs and expectations of the patient | Printed instrument administered by an interviewer | Likert-scale 1–5 (14); open-ended (2) | 30 |

| Moczygemba et al. [27] (2010) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (15); open-ended (3) | 47 |

| Monje-Agudo et al. [28] (2015) | Patient satisfaction assessment survey (Encuesta de valoración de la satisfacción de los pacientes) | Spanish | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–5 (10); open-ended (1) | 154 |

| Moon et al. [15] (2016) | Patient satisfaction survey | English | Undefined | Self-administered printed instrument | Likert-scale 1–4 (9); open-ended (1) | 195 |

*Dichotomic = yes or no questions.

**The instrument was applied by a third partial and the format (printed or digital) was not described by the authors.

Most of the original and validated instruments (seven of nine; 77.8%) [15, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28] were self-administered. All instruments had closed-ended questions and six (six of nine; 66.7%) [15, 21, 22, 26–28] open-ended questions. All instruments were validated with respondents who received CMM services, except the questionnaire developed by Larson et al. [25], which was applied to patients who frequented the community pharmacy but without experiencing the CMM service.

The comparative analysis of the instruments through the checklist developed by Francis et al. [14] is presented in Table 3. The instrument by Armando et al. [21] obtained the highest score, reaching 11 out of 18 points under analysis, followed by the instrument by Larson et al. [25] (10 points) and Moon et al. [15] (10 points).

Critical appraisal of the original validated instruments to measure patient satisfaction with CMM services.

| Checklist item . | Author . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] . | Armando et al. [22] . | Gourley et al. [23] . | Kassam et al. [24] . | Larson et al. [25] . | Lyra Júnior et al. [26] . | Moczygemba et al. [27] . | Monje-Agudo et al. [28] . | Moon et al. [15] . | |

| Conceptual model | |||||||||

| 1. Has the PRO construct to be measured been specifically defined? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Has the intended respondent population been described? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Does the conceptual model address whether a single construct/scale or multiple subscales are expected? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Content validity | |||||||||

| 4. Is there evidence that members of the respondent population were involved in the PRO measure’s development? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5. Is there evidence that content experts were involved in the PRO measure’s development? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Is there a description of the methodology by which items/questions were derived? (e.g. focus groups, interviews)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Reliability | |||||||||

| 7. Is there evidence that the PRO measure´s reliability was tested (e.g. test-retest, internal consistency)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Are reported indices of reliability adequate (e.g. ideal: r ≥ 0.80 adequate ≥ 0.70; or otherwise justified)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Construct validity | |||||||||

| 9. Is there reported quantitative justification that single scale or multiple subscales exist in the PRO measure (e.g. factor analysis, item response theory)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10. Are there findings supporting expected associations with existing PRO measures or other relevant data? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. Are there findings supporting expected differences in scores between relevant known groups? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12. Is the PRO measure intended to measure change over time? If YES, is there evidence of both test-retest reliability AND responsiveness to change? Otherwise, award 1 point if there is an explicit statement that the PRO measure is NOT intended to measure change over time. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SCORING & INTERPRETATION | |||||||||

| 13. Is there documentation on how to score the PRO measure? (e.g. a scoring method such as summing or an algorithm)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14. Has a plan for managing or interpreting missing responses been described? (i.e. how to score incomplete surveys)? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15. Is information provided about to interpreting the PRO measure scores? [e.g. scaling/anchors, (what high and low scores represent), normative data, or a definition of severity (mild to severe)]? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respondent burden & presentation | |||||||||

| 16. Is the time to complete the reported reasonable? OR if is NOT reported, is the number of questions appropriate for the intended application? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 17. Is there a description of the literacy level of the PRO measure? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 18. Is the entire PRO measure available for public viewing? (e.g. published with citation or information provided about how to access a copy)? | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 11 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 |

| Checklist item . | Author . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] . | Armando et al. [22] . | Gourley et al. [23] . | Kassam et al. [24] . | Larson et al. [25] . | Lyra Júnior et al. [26] . | Moczygemba et al. [27] . | Monje-Agudo et al. [28] . | Moon et al. [15] . | |

| Conceptual model | |||||||||

| 1. Has the PRO construct to be measured been specifically defined? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Has the intended respondent population been described? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Does the conceptual model address whether a single construct/scale or multiple subscales are expected? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Content validity | |||||||||

| 4. Is there evidence that members of the respondent population were involved in the PRO measure’s development? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5. Is there evidence that content experts were involved in the PRO measure’s development? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Is there a description of the methodology by which items/questions were derived? (e.g. focus groups, interviews)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Reliability | |||||||||

| 7. Is there evidence that the PRO measure´s reliability was tested (e.g. test-retest, internal consistency)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Are reported indices of reliability adequate (e.g. ideal: r ≥ 0.80 adequate ≥ 0.70; or otherwise justified)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Construct validity | |||||||||

| 9. Is there reported quantitative justification that single scale or multiple subscales exist in the PRO measure (e.g. factor analysis, item response theory)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10. Are there findings supporting expected associations with existing PRO measures or other relevant data? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. Are there findings supporting expected differences in scores between relevant known groups? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12. Is the PRO measure intended to measure change over time? If YES, is there evidence of both test-retest reliability AND responsiveness to change? Otherwise, award 1 point if there is an explicit statement that the PRO measure is NOT intended to measure change over time. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SCORING & INTERPRETATION | |||||||||

| 13. Is there documentation on how to score the PRO measure? (e.g. a scoring method such as summing or an algorithm)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14. Has a plan for managing or interpreting missing responses been described? (i.e. how to score incomplete surveys)? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15. Is information provided about to interpreting the PRO measure scores? [e.g. scaling/anchors, (what high and low scores represent), normative data, or a definition of severity (mild to severe)]? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respondent burden & presentation | |||||||||

| 16. Is the time to complete the reported reasonable? OR if is NOT reported, is the number of questions appropriate for the intended application? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 17. Is there a description of the literacy level of the PRO measure? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 18. Is the entire PRO measure available for public viewing? (e.g. published with citation or information provided about how to access a copy)? | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 11 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 |

Critical appraisal of the original validated instruments to measure patient satisfaction with CMM services.

| Checklist item . | Author . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] . | Armando et al. [22] . | Gourley et al. [23] . | Kassam et al. [24] . | Larson et al. [25] . | Lyra Júnior et al. [26] . | Moczygemba et al. [27] . | Monje-Agudo et al. [28] . | Moon et al. [15] . | |

| Conceptual model | |||||||||

| 1. Has the PRO construct to be measured been specifically defined? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Has the intended respondent population been described? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Does the conceptual model address whether a single construct/scale or multiple subscales are expected? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Content validity | |||||||||

| 4. Is there evidence that members of the respondent population were involved in the PRO measure’s development? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5. Is there evidence that content experts were involved in the PRO measure’s development? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Is there a description of the methodology by which items/questions were derived? (e.g. focus groups, interviews)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Reliability | |||||||||

| 7. Is there evidence that the PRO measure´s reliability was tested (e.g. test-retest, internal consistency)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Are reported indices of reliability adequate (e.g. ideal: r ≥ 0.80 adequate ≥ 0.70; or otherwise justified)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Construct validity | |||||||||

| 9. Is there reported quantitative justification that single scale or multiple subscales exist in the PRO measure (e.g. factor analysis, item response theory)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10. Are there findings supporting expected associations with existing PRO measures or other relevant data? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. Are there findings supporting expected differences in scores between relevant known groups? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12. Is the PRO measure intended to measure change over time? If YES, is there evidence of both test-retest reliability AND responsiveness to change? Otherwise, award 1 point if there is an explicit statement that the PRO measure is NOT intended to measure change over time. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SCORING & INTERPRETATION | |||||||||

| 13. Is there documentation on how to score the PRO measure? (e.g. a scoring method such as summing or an algorithm)? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14. Has a plan for managing or interpreting missing responses been described? (i.e. how to score incomplete surveys)? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15. Is information provided about to interpreting the PRO measure scores? [e.g. scaling/anchors, (what high and low scores represent), normative data, or a definition of severity (mild to severe)]? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respondent burden & presentation | |||||||||

| 16. Is the time to complete the reported reasonable? OR if is NOT reported, is the number of questions appropriate for the intended application? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 17. Is there a description of the literacy level of the PRO measure? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 18. Is the entire PRO measure available for public viewing? (e.g. published with citation or information provided about how to access a copy)? | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 11 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 |

| Checklist item . | Author . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armando et al. [21] . | Armando et al. [22] . | Gourley et al. [23] . | Kassam et al. [24] . | Larson et al. [25] . | Lyra Júnior et al. [26] . | Moczygemba et al. [27] . | Monje-Agudo et al. [28] . | Moon et al. [15] . | |

| Conceptual model | |||||||||

| 1. Has the PRO construct to be measured been specifically defined? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Has the intended respondent population been described? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Does the conceptual model address whether a single construct/scale or multiple subscales are expected? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Content validity | |||||||||