-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yvonne N Brandelli, Sean P Mackinnon, Christine T Chambers, Jennifer A Parker, Adam M Huber, Jennifer N Stinson, Shannon A Johnson, Jennifer P Wilson, Understanding the role of perfectionism in contributing to internalizing symptoms in youth with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 50, Issue 2, February 2025, Pages 175–186, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsae100

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Youth with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) experience elevated rates of internalizing symptoms, although more research is required to understand this phenomenon. Perfectionism, a multidimensional personality trait that involves dimensions such as striving for flawlessness (self-oriented perfectionism) and feeling that others demand perfection (socially-prescribed perfectionism), is a well-known risk factor for internalizing symptoms that has received minimal attention in pediatric populations. Preregistered hypotheses explored the relationships between youth and parent perfectionism and symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with JIA, as mediated by (a) youth/parent negative self-evaluations and (b) youth self-concealment.

One hundred fifty-six dyads comprised of youth (13–18 years) with JIA and a caregiver completed online questionnaires about trait perfectionism, negative self-evaluations (i.e., pain catastrophizing and fear of pain), self-concealment, and internalizing symptoms.

Positive relationships were observed between parent/youth self-oriented perfectionism and negative self-evaluations, youth self-oriented perfectionism and internalizing symptoms, and youth negative self-evaluations and internalizing symptoms. Parent self-oriented perfectionism was negatively related to youth depression symptoms. Indirect effects were observed for youth self-oriented perfectionism predicting anxiety and depression symptoms through pain catastrophizing (a1b1 = 0.13 and 0.12, 95% CI [.03, .24 and .03, .22], respectively). Exploratory mediations suggested youth socially-prescribed perfectionism might predict internalizing symptoms directly and indirectly through self-concealment.

Youth and parent perfectionism are implicated in the internalizing symptoms of youth with JIA and may manifest through youth negative self-evaluations (e.g., catastrophic thoughts) and self-concealment. While future research is needed, screening for perfectionistic tendencies in this population may help guide assessment, prevention, and treatment efforts.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting nearly 8 million children worldwide (Petty et al., 2021). Pain is one of the most common symptoms (Canadian Paediatric Society, 2009), with one study recording that youth experienced pain on average 73% of days across 2 months (Schanberg et al., 2003). Both the diagnosis of a chronic health condition and the increased rates of pain put youth with JIA at risk for increased anxiety and depression (Brandelli et al., 2023; Fair et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). Fair et al. (2019) found that many youth with JIA experience clinically significant symptoms of depression (7%–36%) and anxiety (7%–64%). Moreover, these estimates were made before the COVID-19 pandemic, thus rates have likely increased (Racine et al., 2021). Given the elevated rates of anxiety and depression in this population and the negative effects that this can have on one’s life, it is critical for research to understand these experiences to better tailor assessment, prevention, and treatment efforts. As the factors contributing to internalizing symptoms are complex and multifactorial (e.g., Jastrowski Mano et al., 2019; Soltani et al., 2019), and treatments focused solely on symptoms may overlook underlying maintaining factors, it is important to have a comprehensive understanding of the factors involved.

One underlying factor observed in broader populations that may maintain internalizing symptoms if unaddressed (Galloway et al., 2022) is perfectionism. Perfectionism is a multidimensional personality trait that involves striving for flawlessness, setting exceedingly high standards, making overly critical self-evaluations, and feeling pressure to meet standards imposed by others (Frost et al., 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Hewitt and Flett’s (1991) interpersonal model of perfectionism divides perfectionism into three dimensions based on the person demanding perfection. Self-oriented perfectionism involves rigidly and inflexibly demanding perfection of oneself (e.g., children demand perfect academic performance of themselves, even on high pain days). Socially-prescribed perfectionism is the perception that others are demanding perfection of oneself, which is typically perceived as unfair or unjust (e.g., children believe that their parents require perfect academic performance, and they must push through the pain to achieve it). Finally, other-oriented perfectionism is demanding perfection of other people, typically in an entitled and narcissistic fashion (e.g., a parent demanding that their child have perfect academic performance even during a flare, and harshly critiquing them when they do not). Perfectionistic traits are posited to emerge during childhood in response to the child’s own characteristics (e.g., temperament, ability) and their broader family and sociocultural environment (e.g., expectations, contingencies, social learning, social reactions, attachment) (Flett et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2022).

Perfectionism is a well-known risk factor for anxiety and depression in healthy youth (e.g., Affrunti & Woodruff-Borden, 2014; Morris & Lomax, 2014) that has begun to receive attention for its role in the context of adult pain-related conditions (Behrens, 2017; Flett et al., 2011; Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2007; Molnar et al., 2016). While overall perfectionism has received minimal attention in the pediatric and pain literatures (Randall et al., 2018a), recently Piercy et al. (2020) found that both youth and parent perfectionism were positively associated with internalizing symptoms in youth with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

In response to clinical observations regarding the co-occurrence of perfectionism and pediatric pain, there has been a call to better understand the mechanisms by which youth and parent perfectionism contribute to anxiety and depression in pediatric populations (Randall et al., 2018a). Randall et al. (2018a) proposed that perfectionism and pain are related through biopsychosocial processes (e.g., stress; inflammation; altered pain processing; cognitive and behavioral factors that precipitate, maintain, or exacerbate pain; interpersonal challenges), and that perfectionism in youth experiencing pain and their parents amplifies challenges such as internalizing symptoms by undermining coping and recovery efforts. Thus, it may be that the pain-related condition imposes limitations on individuals with perfectionism that they (and others) cannot accept, creating a disconnect between their goals and capabilities which leads to maladaptive psychosocial processes (e.g., unhelpful cognitions, avoidance behaviors) that ultimately exacerbate internalizing symptoms.

Support exists for some of these relationships in the pediatric pain literature, wherein dimensions of youth perfectionism have been associated with greater catastrophic thinking about pain (i.e., unhelpful cognitions including ruminating, magnifying, and feeling helpless), and more fears of pain (e.g., avoiding situations that may provoke pain) (Randall et al., 2018b). Similarly, dimensions of parent perfectionism were related to youth and parent catastrophizing and youth pain-related fear (Randall et al., 2018b). To date, these relationships have not been explored in the JIA population.

Building off these theories, Molnar et al. (2016) developed The Stress and Coping Cyclical Amplification Model of Perfectionism in Illness (SCCAMPI). This model suggests that individuals high in perfectionism may be susceptible to amplified stress paired with maladaptive coping through various pathways which may exacerbate health-related outcomes. Although this model does not include parents, given that parent perfectionism is related to child perfectionism (Affrunti & Woodruff-Borden, 2014), and that parents must also adjust to the diagnosis, it is postulated that parents’ own perfectionism may also be implicated through these pathways.

One pathway describes how individuals high in perfectionism may engage in negative self-evaluations when they are unable to meet their impossibly high standards (Molnar et al., 2016). Although a chronic disease such as JIA may encourage some individuals to become more flexible with their goals, individuals high in self-oriented perfectionism may be unwilling to re-adjust their goals to account for their pain and disease flares. As such, they may have a heightened awareness of the limits imposed by JIA (e.g., more catastrophic thoughts and pain-related fears), but their unwillingness to adjust their goals may exacerbate negative self-evaluations and self-scrutiny, thus leading to more internalizing symptoms in youth.

Another pathway suggests individuals with perfectionism maintain their self-image by hiding their unappealing characteristics through self-concealment (Molnar et al., 2016). Self-concealment refers to hiding symptoms that might be stigmatized from public scrutiny; in the context of JIA, this refers to hiding pain and symptoms from other people. The “invisibility” of JIA pain emphasizes the need for youth to communicate their experiences and advocate for adaptations. Youth high in self-oriented and socially-prescribed perfectionism may conceal their diagnosis and/or symptoms because they want to achieve perfection and convey this to others. This may also be true for youth with parents high in other-oriented perfectionism because their environment expects perfection from them. Although in the short-term there may be benefits to this (e.g., appearing “normal”), concealment may have undue long-term consequences for the individual’s health and well-being (Larson & Chastain, 1990). As such, self-concealment may mediate the relationship between the youth’s own perfectionism (or the parent’s other-oriented perfectionism) and internalizing symptoms.

In sum, although important advances have been made in recognizing that perfectionism contributes to one’s mental health, especially in the context of pain-related conditions, these pathways remain untested. By understanding the risk factors and mechanisms for internalizing symptoms, we can better focus interventions. Furthermore, this research has not yet been applied to youth with JIA. Unlike other populations, youth with JIA face an idiopathic, variable (with unpredictable flares), chronic, invisible, and often stigmatized disease. This unique combination of characteristics may amplify and/or alter the presentation of perfectionism, internalizing symptoms, or their mechanisms. For example, compared to a diagnosis of chronic pain, the stigma of having arthritis, a disease often associated with older populations, may increase one’s likelihood of hiding their symptoms and portraying their perfection. Given these nuanced differences between populations, it is important for research to adopt a population-specific approach. The objective of this study is to examine the relationships between youth and parent perfectionism and internalizing symptoms in youth with JIA. It was hypothesized that:

(H1) Youth and parent self-oriented perfectionism would be associated with increased anxiety and depression in youth, and these relationships would be mediated by negative self-evaluations (as measured by pain catastrophizing and fear of pain in youth and parents).

(H2) Youth self-oriented and socially-prescribed perfectionism and parent other-oriented perfectionism would be associated with heightened anxiety and depression in youth, and these relationships would be mediated by the youth’s self-concealment.

Methods

Study design

This dyadic (youth/parent), Internet-based, cross-sectional research was approved by the IWK Health’s Research Ethics Board. Consistent with patient-oriented research, this study was conducted in consultation with a leader in patient engagement (IJ), and in partnership with Cassie and Friends, a Canadian parent-led organization for families of children with rheumatic diseases (www.cassieandfriends.ca). Three youth and parent partners became involved during the initial phases of this study (Brandelli et al., 2022) and provided input on study conceptualization through to dissemination. This study was preregistered prior to collecting and analyzing the data. The preregistration, deidentified data, syntax, and associated documents are openly available through Open Science Framework (OSF; https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5WU8F).

Participants

Participants included English-speaking youth between 13 and 18 years old with a diagnosis of JIA and one of their parents or caregivers (herein referred to as parents). Purposeful recruitment occurred worldwide between November 2021 and April 2023 primarily through online and social media platforms (e.g., arthritis and pain communities, Facebook and Instagram advertisements, blog posts). Additional strategies included recruitment through previous studies, posters at clinics, research registries, and industry partnerships.

Power analyses are in the preregistered plan on OSF. The aim was to recruit 319 dyads or to terminate data collection by Spring 2023 given funding timelines, whichever came first. Repeated interference by sham respondents (e.g., disingenuous and software-automated responses) slowed data collection considerably. Recruitment efforts produced less than the required sample size; although, post hoc power analyses demonstrated most models retained at least 70% power to detect indirect effects. Two hundred and six dyads consented online, 33 were ineligible given their diagnosis or age and 17 stopped after providing consent, resulting in a final sample of 156 dyads.

Missing data were complex, as not all dyads had data for both members. The survey was fully completed by most parents (n = 129; 82.7%) and youth (n = 122; 78.2%). Some parents (n = 11; 7.0%) and youth (n = 7; 4.5%) provided partial data, and the rest did not complete the survey at all (n = 16; 10.3% and n = 27; 17.3%, respectively). In total, 104 dyads (66%) had complete data (i.e., both parents and children completed all measures). All viable data, including partial data, were analyzed when appropriate.

Measures

Demographics and medical variables

Youth and parents reported on ethnicity (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2022) and other demographic (e.g., age, sex, gender), medical (e.g., diagnosis, disease status), and pain-related (Birnie et al., 2019) variables.

Perfectionism

Youth perfectionism

The 22-item Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS; Flett et al., 2016) assessed two dimensions of perfectionism on a scale of 1 (False — not at all true of me) to 5 (very true of me): self-oriented (12 items) and socially-prescribed (10 items). In psychometric studies the CAPS has demonstrated good internal consistency, concurrent validity, and test–retest reliability (Flett et al., 2016), including in this study (α = .90 – .91).

Parent perfectionism

Parent perfectionism was assessed using two subscales from the Big Three Perfectionism Scale (BTPS; Smith et al., 2016) on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree): self-oriented (5 items), and other-oriented (5 items). Research has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .88 – .84 in this study) and preliminary evidence for convergent and divergent validity (Smith et al., 2016).

Pain catastrophizing (negative self-evaluation)

Youth pain catastrophizing

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Children (PCS-C; Crombez et al., 2003, 2012) measures pain-related maladaptive thinking patterns (i.e., catastrophizing). Thirteen items are administered on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) totaling three dimensions of pain catastrophizing (helplessness, magnification, and rumination). This measure has been used in JIA samples (Brandelli et al., 2023), and has demonstrated good internal consistency in the past (Crombez et al., 2003) and current research (α = .95).

Parent pain catastrophizing

Parent catastrophizing was assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Parents (PCS-P; Crombez et al., 2012), which uses the same 13-items as the PCS-C, with modified language. This measure has strong psychometrics (Goubert et al., 2006), including in JIA samples (Brandelli et al., 2019). Internal consistency in this study was .94.

Fear of pain (negative self-evaluation)

Youth fear of pain

The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Child—Short Form (FOPQC-SF; Heathcote et al., 2020) measures pain-related fear and two subdimensions: fear and avoidance. Ten items were rated on a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The validation study showed strong construct validity, criterion validity, test–retest reliability; and good internal consistency (Heathcote et al., 2020). Internal consistency in this study was .89.

Parent fear of pain

Parent pain-related fears were measured using the 21-item Parent Fear of Pain Questionnaire (PFOPQ; Simons et al., 2015). This scale compiles four dimensions of pain-related fear in parents: fear, avoidance, school, and movement. Items were rated on a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Excellent psychometrics have been observed (Simons et al., 2015), including in JIA samples (Brandelli et al., 2019) and this study (α = .94).

Youth self-concealment

Youth self-concealment was assessed using the 5-item concealment subscale of the Health-Related Felt Stigma and Concealment Questionnaire (FSC-Q; Laird et al., 2020). While developed for youth with abdominal symptoms, the instructions were modified to suit a JIA population (i.e., ““Symptoms” refers to any arthritis symptoms, including: aches, pain, stiffness, swelling”). Items were rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This subscale demonstrated good psychometric properties in the validation study (Laird et al., 2020) and the present study (α = .90).

Youth internalizing symptoms

Internalizing symptoms were assessed with the 25-item youth self-report version of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale Short Version (RCADS-25; Ebesutani et al., 2012), a measure that has been used in youth with JIA (Brandelli et al., 2023). Youth responded to 15 items about feelings of anxiety and 10 items about feelings of depression on a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (always). This scale, validated on healthy and clinical samples of youth, displays good internal consistency and acceptable concurrent validity (Ebesutani et al., 2012). Internal consistency in this study ranged from .89 to .91.

Procedures

Participants self-selected into this study. After one dyad member verified their eligibility through a screening questionnaire, youth and parents were emailed a unique survey link where they independently provided informed consent, confirmed their eligibility, and completed a 45-min battery of questionnaires online. Eligibility was assessed by both the parent and child independently. Questions were mandatory; however, participants had the option of selecting “prefer not to answer” for all items which was treated as missing. Completed participants were offered a $15 CAD online gift card and completed dyads were also offered the option of entering a draw to win one of two pairs of $250 CAD gift cards.

Safeguards protected against sham responses (Teitcher et al., 2015). This included a screening questionnaire, attention checks, “spam trap” questions, captchas, passwords, and the prevention of multiple submissions from the same Internet Protocol address.

Analytic plan

Youth–parent dyads were paired, and total scores were calculated for each scale (items were averaged such that higher values indicate greater levels of the variable). Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were calculated first. Path analysis using the lavaan() package (Rosseel, 2012) in R was used to test hypotheses. Analyses were informed by actor–partner interdependence modeling with distinguishable dyads (Ledermann et al., 2011), exploring associations between variables at the individual (i.e., actor and partner effects) and partner (i.e., interactions between the actor and the partner effects) levels (Cook & Kenny, 2005). Models used maximum likelihood robust estimation and robust estimates of standard errors. Indirect effects were calculated using bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples. Preregistered hypotheses were tested in six path models, wherein standardized paths, covariances, and R2 values are reported. Covariates (e.g., age, sex) were not included due to sample size limitations. A full information maximum likelihood approach was used to account for missing data.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 129 adolescents with JIA and 140 parents. Table 1 summarizes demographic information. The sample consisted of largely female youth (67.9%) and parents (94.9%) with mean ages of 15.29 (SD = 1.62) and 45.24 (SD = 4.87). Over half the sample was currently experiencing active disease and chronic pain (i.e., pain more days than not over the past 3 months). The usual pain severity experienced by youth was 4.96 (SD = 2.23) on the 11-point Numeric Rating Scale, slightly higher than other samples (Schanberg et al., 2003). Using clinical cutoffs, many youth had anxiety (25%) and depression (36%) in the borderline/clinical ranges. The mean scores for pain catastrophizing, perfectionism, and fear of pain were consistent with other chronic pain samples (Heathcote et al., 2020; Randall et al., 2018b). Weak to moderate positive correlations were generally observed within and between youth and parent measures of perfectionism, pain catastrophizing, fear of pain, and anxiety and depression. Two notable exceptions include the lack of correlation between dimensions of parent perfectionism and youth anxiety and depression, and the weak/absent correlations between youth self-concealment and youth perfectionism (Table 2).

| Parent (n = 140) . | Youth (n = 129) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics and medical variables . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . |

| Participant demographics | ||

| Age (years) | 45.24 ± 4.87 (33, 57)a | 15.29 ± 1.62 (13, 18)b |

| Sex (female)b | — | 110 (70.5) |

| Genderb | ||

| Mother/Girl | 148 (94.9) | 106 (67.9) |

| Father/Boy | 8 (5.1) | 46 (29.5) |

| Other (transgender, nonbinary, gender fluid) | — | 4 (2.5) |

| Ethnicityc | ||

| Aboriginal | 7 (4.5) | 9 (5.8) |

| Black | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| East/Southeast Asian | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) |

| South Asian | 4 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) |

| White | 123 (78.8) | 110 (70.5) |

| Other (Jewish, West Asian, Latin American) | 5 (3.2) | 4 (2.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (1.3) | 1 (.6) |

| Country of residence | ||

| Canada | 96 (68.6) | 95 (74.2) |

| United Kingdom | 24 (17.1) | 19 (14.8) |

| United States | 16 (11.4) | 11 (8.6) |

| Other (Ireland, South Africa, Australia) | 4 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) |

| Income (in CAD) | ||

| <$50,000 | 16 (11.5) | — |

| $50,000–99,999 | 42 (30.0) | — |

| $100,000–149,999 | 29 (20.7) | — |

| >$150,000 | 36 (25.7) | — |

| Prefer not to answer | 17 (12.1) | — |

| Youth medical characteristics | ||

| Diagnosisb,d | ||

| Polyarticular arthritis | — | 37 (23.9) |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | — | 27 (17.4) |

| Oligoarticular arthritis | — | 26 (16.8) |

| Systemic arthritis | — | 17 (11.0) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | — | 10 (6.5) |

| Undifferentiated arthritis or unknowne | — | 38 (24.5) |

| Age at diagnosisb,f | — | 8.09 ± 4.72 (0, 16) |

| Current disease activity (active/flare) | 87 (62.1) | 75 (59.1)g |

| Pain severity—Current VAS (0–10) | 3.45 ± 3.04 (0, 10) | 2.80 ± 2.90 (0, 10)g |

| Pain severity—Usual VAS (0–10) | 4.93 ± 2.15 (0, 10) | 4.96 ± 2.23 (0, 10)h |

| Pain frequency—Past month | ||

| Not at all | 27 (19.3) | 26 (20.5)g |

| 1–14 days | 38 (27.2) | 37 (29.1)g |

| 15–28 days | 26 (18.6) | 14 (11.0)g |

| Daily | 49 (35.0) | 50 (39.4)g |

| Pain—Currently experiencing chronic pain | 50 (35.7) | 50 (39.4)h |

| Parent (n = 140) . | Youth (n = 129) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics and medical variables . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . |

| Participant demographics | ||

| Age (years) | 45.24 ± 4.87 (33, 57)a | 15.29 ± 1.62 (13, 18)b |

| Sex (female)b | — | 110 (70.5) |

| Genderb | ||

| Mother/Girl | 148 (94.9) | 106 (67.9) |

| Father/Boy | 8 (5.1) | 46 (29.5) |

| Other (transgender, nonbinary, gender fluid) | — | 4 (2.5) |

| Ethnicityc | ||

| Aboriginal | 7 (4.5) | 9 (5.8) |

| Black | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| East/Southeast Asian | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) |

| South Asian | 4 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) |

| White | 123 (78.8) | 110 (70.5) |

| Other (Jewish, West Asian, Latin American) | 5 (3.2) | 4 (2.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (1.3) | 1 (.6) |

| Country of residence | ||

| Canada | 96 (68.6) | 95 (74.2) |

| United Kingdom | 24 (17.1) | 19 (14.8) |

| United States | 16 (11.4) | 11 (8.6) |

| Other (Ireland, South Africa, Australia) | 4 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) |

| Income (in CAD) | ||

| <$50,000 | 16 (11.5) | — |

| $50,000–99,999 | 42 (30.0) | — |

| $100,000–149,999 | 29 (20.7) | — |

| >$150,000 | 36 (25.7) | — |

| Prefer not to answer | 17 (12.1) | — |

| Youth medical characteristics | ||

| Diagnosisb,d | ||

| Polyarticular arthritis | — | 37 (23.9) |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | — | 27 (17.4) |

| Oligoarticular arthritis | — | 26 (16.8) |

| Systemic arthritis | — | 17 (11.0) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | — | 10 (6.5) |

| Undifferentiated arthritis or unknowne | — | 38 (24.5) |

| Age at diagnosisb,f | — | 8.09 ± 4.72 (0, 16) |

| Current disease activity (active/flare) | 87 (62.1) | 75 (59.1)g |

| Pain severity—Current VAS (0–10) | 3.45 ± 3.04 (0, 10) | 2.80 ± 2.90 (0, 10)g |

| Pain severity—Usual VAS (0–10) | 4.93 ± 2.15 (0, 10) | 4.96 ± 2.23 (0, 10)h |

| Pain frequency—Past month | ||

| Not at all | 27 (19.3) | 26 (20.5)g |

| 1–14 days | 38 (27.2) | 37 (29.1)g |

| 15–28 days | 26 (18.6) | 14 (11.0)g |

| Daily | 49 (35.0) | 50 (39.4)g |

| Pain—Currently experiencing chronic pain | 50 (35.7) | 50 (39.4)h |

Note. Parent data are used for parent demographics, and parent report data were used for youth medical characteristics. Percent was calculated based on number of participants who completed the question rather than the total N.

n = 139.

Data from parents/youth were combined to achieve an N = 156. Data that matched were used when possible. If not possible, youth data were used before parent data for demographic information, and parent data were used before youth data for medical information.

Participants could select more than one response.

n = 155.

Three participants indicated also having a diagnosis of autoimmune arthritis, juvenile dermatomyositis, and scleroderma.

n = 152.

n = 127.

n = 125.

| Parent (n = 140) . | Youth (n = 129) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics and medical variables . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . |

| Participant demographics | ||

| Age (years) | 45.24 ± 4.87 (33, 57)a | 15.29 ± 1.62 (13, 18)b |

| Sex (female)b | — | 110 (70.5) |

| Genderb | ||

| Mother/Girl | 148 (94.9) | 106 (67.9) |

| Father/Boy | 8 (5.1) | 46 (29.5) |

| Other (transgender, nonbinary, gender fluid) | — | 4 (2.5) |

| Ethnicityc | ||

| Aboriginal | 7 (4.5) | 9 (5.8) |

| Black | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| East/Southeast Asian | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) |

| South Asian | 4 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) |

| White | 123 (78.8) | 110 (70.5) |

| Other (Jewish, West Asian, Latin American) | 5 (3.2) | 4 (2.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (1.3) | 1 (.6) |

| Country of residence | ||

| Canada | 96 (68.6) | 95 (74.2) |

| United Kingdom | 24 (17.1) | 19 (14.8) |

| United States | 16 (11.4) | 11 (8.6) |

| Other (Ireland, South Africa, Australia) | 4 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) |

| Income (in CAD) | ||

| <$50,000 | 16 (11.5) | — |

| $50,000–99,999 | 42 (30.0) | — |

| $100,000–149,999 | 29 (20.7) | — |

| >$150,000 | 36 (25.7) | — |

| Prefer not to answer | 17 (12.1) | — |

| Youth medical characteristics | ||

| Diagnosisb,d | ||

| Polyarticular arthritis | — | 37 (23.9) |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | — | 27 (17.4) |

| Oligoarticular arthritis | — | 26 (16.8) |

| Systemic arthritis | — | 17 (11.0) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | — | 10 (6.5) |

| Undifferentiated arthritis or unknowne | — | 38 (24.5) |

| Age at diagnosisb,f | — | 8.09 ± 4.72 (0, 16) |

| Current disease activity (active/flare) | 87 (62.1) | 75 (59.1)g |

| Pain severity—Current VAS (0–10) | 3.45 ± 3.04 (0, 10) | 2.80 ± 2.90 (0, 10)g |

| Pain severity—Usual VAS (0–10) | 4.93 ± 2.15 (0, 10) | 4.96 ± 2.23 (0, 10)h |

| Pain frequency—Past month | ||

| Not at all | 27 (19.3) | 26 (20.5)g |

| 1–14 days | 38 (27.2) | 37 (29.1)g |

| 15–28 days | 26 (18.6) | 14 (11.0)g |

| Daily | 49 (35.0) | 50 (39.4)g |

| Pain—Currently experiencing chronic pain | 50 (35.7) | 50 (39.4)h |

| Parent (n = 140) . | Youth (n = 129) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics and medical variables . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . | N (%) or M ± SD (Min, Max) . |

| Participant demographics | ||

| Age (years) | 45.24 ± 4.87 (33, 57)a | 15.29 ± 1.62 (13, 18)b |

| Sex (female)b | — | 110 (70.5) |

| Genderb | ||

| Mother/Girl | 148 (94.9) | 106 (67.9) |

| Father/Boy | 8 (5.1) | 46 (29.5) |

| Other (transgender, nonbinary, gender fluid) | — | 4 (2.5) |

| Ethnicityc | ||

| Aboriginal | 7 (4.5) | 9 (5.8) |

| Black | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) |

| East/Southeast Asian | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) |

| South Asian | 4 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) |

| White | 123 (78.8) | 110 (70.5) |

| Other (Jewish, West Asian, Latin American) | 5 (3.2) | 4 (2.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (1.3) | 1 (.6) |

| Country of residence | ||

| Canada | 96 (68.6) | 95 (74.2) |

| United Kingdom | 24 (17.1) | 19 (14.8) |

| United States | 16 (11.4) | 11 (8.6) |

| Other (Ireland, South Africa, Australia) | 4 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) |

| Income (in CAD) | ||

| <$50,000 | 16 (11.5) | — |

| $50,000–99,999 | 42 (30.0) | — |

| $100,000–149,999 | 29 (20.7) | — |

| >$150,000 | 36 (25.7) | — |

| Prefer not to answer | 17 (12.1) | — |

| Youth medical characteristics | ||

| Diagnosisb,d | ||

| Polyarticular arthritis | — | 37 (23.9) |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | — | 27 (17.4) |

| Oligoarticular arthritis | — | 26 (16.8) |

| Systemic arthritis | — | 17 (11.0) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | — | 10 (6.5) |

| Undifferentiated arthritis or unknowne | — | 38 (24.5) |

| Age at diagnosisb,f | — | 8.09 ± 4.72 (0, 16) |

| Current disease activity (active/flare) | 87 (62.1) | 75 (59.1)g |

| Pain severity—Current VAS (0–10) | 3.45 ± 3.04 (0, 10) | 2.80 ± 2.90 (0, 10)g |

| Pain severity—Usual VAS (0–10) | 4.93 ± 2.15 (0, 10) | 4.96 ± 2.23 (0, 10)h |

| Pain frequency—Past month | ||

| Not at all | 27 (19.3) | 26 (20.5)g |

| 1–14 days | 38 (27.2) | 37 (29.1)g |

| 15–28 days | 26 (18.6) | 14 (11.0)g |

| Daily | 49 (35.0) | 50 (39.4)g |

| Pain—Currently experiencing chronic pain | 50 (35.7) | 50 (39.4)h |

Note. Parent data are used for parent demographics, and parent report data were used for youth medical characteristics. Percent was calculated based on number of participants who completed the question rather than the total N.

n = 139.

Data from parents/youth were combined to achieve an N = 156. Data that matched were used when possible. If not possible, youth data were used before parent data for demographic information, and parent data were used before youth data for medical information.

Participants could select more than one response.

n = 155.

Three participants indicated also having a diagnosis of autoimmune arthritis, juvenile dermatomyositis, and scleroderma.

n = 152.

n = 127.

n = 125.

| Variable . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Youth anxiety (self-report) | — | ||||||||||

| 2 | Youth depression (self-report) | .73*** | — | |||||||||

| 3 | Youth self-oriented perfectionism | .35*** | .28** | — | ||||||||

| 4 | Youth socially-prescribed perfectionism | .32*** | .32*** | .49*** | — | |||||||

| 5 | Parent self-oriented perfectionism | .11 | −.07 | .29** | .14 | — | ||||||

| 6 | Parent other-oriented perfectionism | .05 | −.04 | .20* | .30*** | .63*** | — | |||||

| 7 | Youth pain catastrophizing | .57*** | .55*** | .25** | .27** | .17 | .12 | — | ||||

| 8 | Parent pain catastrophizing | .08 | .21* | .05 | −.03 | .27** | .24** | .31*** | — | |||

| 9 | Youth fear of pain | .55*** | .54*** | .14 | .15 | .17 | .12 | .66*** | .33*** | — | ||

| 10 | Parent fear of pain | .15 | .23* | −.04 | .05 | .30*** | .33*** | .31*** | .71*** | .47*** | — | |

| 11 | Youth self-concealment | .30*** | .28** | .10 | .20* | −.03 | .13 | .22* | .06 | .30*** | .20* | — |

| N | 126 | 126 | 126 | 126 | 139 | 139 | 126 | 138 | 126 | 138 | 126 | |

| M | 12.85 | 11.56 | 3.36 | 2.51 | 2.58 | 1.97 | 1.49 | 1.61 | 1.66 | 1.19 | 3.32 | |

| SD | 8.23 | 6.82 | .82 | .86 | .90 | .67 | 1.01 | .88 | .90 | .74 | 1.08 | |

| Alpha | .89 | .91 | .91 | .90 | .88 | .84 | .95 | .94 | .89 | .94 | .90 | |

| Variable . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Youth anxiety (self-report) | — | ||||||||||

| 2 | Youth depression (self-report) | .73*** | — | |||||||||

| 3 | Youth self-oriented perfectionism | .35*** | .28** | — | ||||||||

| 4 | Youth socially-prescribed perfectionism | .32*** | .32*** | .49*** | — | |||||||

| 5 | Parent self-oriented perfectionism | .11 | −.07 | .29** | .14 | — | ||||||

| 6 | Parent other-oriented perfectionism | .05 | −.04 | .20* | .30*** | .63*** | — | |||||

| 7 | Youth pain catastrophizing | .57*** | .55*** | .25** | .27** | .17 | .12 | — | ||||

| 8 | Parent pain catastrophizing | .08 | .21* | .05 | −.03 | .27** | .24** | .31*** | — | |||

| 9 | Youth fear of pain | .55*** | .54*** | .14 | .15 | .17 | .12 | .66*** | .33*** | — | ||

| 10 | Parent fear of pain | .15 | .23* | −.04 | .05 | .30*** | .33*** | .31*** | .71*** | .47*** | — | |

| 11 | Youth self-concealment | .30*** | .28** | .10 | .20* | −.03 | .13 | .22* | .06 | .30*** | .20* | — |

| N | 126 | 126 | 126 | 126 | 139 | 139 | 126 | 138 | 126 | 138 | 126 | |

| M | 12.85 | 11.56 | 3.36 | 2.51 | 2.58 | 1.97 | 1.49 | 1.61 | 1.66 | 1.19 | 3.32 | |

| SD | 8.23 | 6.82 | .82 | .86 | .90 | .67 | 1.01 | .88 | .90 | .74 | 1.08 | |

| Alpha | .89 | .91 | .91 | .90 | .88 | .84 | .95 | .94 | .89 | .94 | .90 | |

Note.

Correlation is significant at the <.001 level.

Correlation is significant at the .01 level.

Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2 tailed).

| Variable . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Youth anxiety (self-report) | — | ||||||||||

| 2 | Youth depression (self-report) | .73*** | — | |||||||||

| 3 | Youth self-oriented perfectionism | .35*** | .28** | — | ||||||||

| 4 | Youth socially-prescribed perfectionism | .32*** | .32*** | .49*** | — | |||||||

| 5 | Parent self-oriented perfectionism | .11 | −.07 | .29** | .14 | — | ||||||

| 6 | Parent other-oriented perfectionism | .05 | −.04 | .20* | .30*** | .63*** | — | |||||

| 7 | Youth pain catastrophizing | .57*** | .55*** | .25** | .27** | .17 | .12 | — | ||||

| 8 | Parent pain catastrophizing | .08 | .21* | .05 | −.03 | .27** | .24** | .31*** | — | |||

| 9 | Youth fear of pain | .55*** | .54*** | .14 | .15 | .17 | .12 | .66*** | .33*** | — | ||

| 10 | Parent fear of pain | .15 | .23* | −.04 | .05 | .30*** | .33*** | .31*** | .71*** | .47*** | — | |

| 11 | Youth self-concealment | .30*** | .28** | .10 | .20* | −.03 | .13 | .22* | .06 | .30*** | .20* | — |

| N | 126 | 126 | 126 | 126 | 139 | 139 | 126 | 138 | 126 | 138 | 126 | |

| M | 12.85 | 11.56 | 3.36 | 2.51 | 2.58 | 1.97 | 1.49 | 1.61 | 1.66 | 1.19 | 3.32 | |

| SD | 8.23 | 6.82 | .82 | .86 | .90 | .67 | 1.01 | .88 | .90 | .74 | 1.08 | |

| Alpha | .89 | .91 | .91 | .90 | .88 | .84 | .95 | .94 | .89 | .94 | .90 | |

| Variable . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Youth anxiety (self-report) | — | ||||||||||

| 2 | Youth depression (self-report) | .73*** | — | |||||||||

| 3 | Youth self-oriented perfectionism | .35*** | .28** | — | ||||||||

| 4 | Youth socially-prescribed perfectionism | .32*** | .32*** | .49*** | — | |||||||

| 5 | Parent self-oriented perfectionism | .11 | −.07 | .29** | .14 | — | ||||||

| 6 | Parent other-oriented perfectionism | .05 | −.04 | .20* | .30*** | .63*** | — | |||||

| 7 | Youth pain catastrophizing | .57*** | .55*** | .25** | .27** | .17 | .12 | — | ||||

| 8 | Parent pain catastrophizing | .08 | .21* | .05 | −.03 | .27** | .24** | .31*** | — | |||

| 9 | Youth fear of pain | .55*** | .54*** | .14 | .15 | .17 | .12 | .66*** | .33*** | — | ||

| 10 | Parent fear of pain | .15 | .23* | −.04 | .05 | .30*** | .33*** | .31*** | .71*** | .47*** | — | |

| 11 | Youth self-concealment | .30*** | .28** | .10 | .20* | −.03 | .13 | .22* | .06 | .30*** | .20* | — |

| N | 126 | 126 | 126 | 126 | 139 | 139 | 126 | 138 | 126 | 138 | 126 | |

| M | 12.85 | 11.56 | 3.36 | 2.51 | 2.58 | 1.97 | 1.49 | 1.61 | 1.66 | 1.19 | 3.32 | |

| SD | 8.23 | 6.82 | .82 | .86 | .90 | .67 | 1.01 | .88 | .90 | .74 | 1.08 | |

| Alpha | .89 | .91 | .91 | .90 | .88 | .84 | .95 | .94 | .89 | .94 | .90 | |

Note.

Correlation is significant at the <.001 level.

Correlation is significant at the .01 level.

Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2 tailed).

Hypothesis 1: negative self-evaluations mediating the relationships between youth/parent self-oriented perfectionism and youth anxiety and depression

Four path analyses were completed to test the above-mentioned hypothesis by varying the mediator (pain catastrophizing and fear of pain) and outcome (anxiety and depression) one at a time across analyses. Across all models, there were significant, positive covariances between youth and parent self-oriented perfectionism, pain catastrophizing, and fear of pain. That is, youth and parents were more alike on these traits than would be expected due to chance.

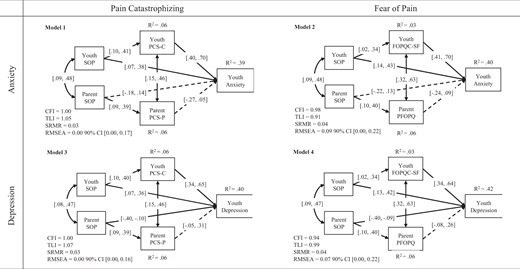

In model 1 (Figure 1), standardized regression coefficients confirmed that youth self-oriented perfectionism was positively related to youth catastrophizing, and parent self-oriented perfectionism was positively related to parent catastrophizing, each accounting for 6% of the variance. This model predicted 39% of the variance in youth anxiety; however, not all paths were statistically significant. Specifically, youth self-oriented perfectionism directly and indirectly predicted anxiety through youth catastrophizing (a1b1 = 0.13, 95% CI [.03, .24]). Parent catastrophizing, however, was not related to anxiety, nor was parent self-oriented perfectionism (directly or indirectly; a2b2 = −0.03, 95% CI [−.08, .02]).

Path analyses for hypothesis 1 predicting the effects of youth/parent self-oriented perfectionism on youth mental health through pain catastrophizing and fear of pain. Note. The 95% confidence intervals for standardized coefficients are reported. Solid lines represent p < .05. Arrows pointing toward the factor represent residual variance. CFI, Robust Comparative Fit Index; FOPQC-SF, Fear of Pain Questionnaire Child—Short Form; PCS-C, Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Children; PCS-P, Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Parents; PFOPQ, Parent Fear of Pain Questionnaire; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SOP, Self-Oriented Perfectionism; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; TLI, Robust Tucker-Lewis Index.

These results were largely maintained in model 2 (Figure 1) wherein the mediator was replaced with fear of pain. Youth self-oriented perfectionism accounted for 3% of the variance in fear of pain, and parent self-oriented perfectionism accounted for 6% of the variance in parent fear of pain. The whole model accounted for 40% of the variance in youth anxiety. Youth self-oriented perfectionism and fear of pain each directly contributed to anxiety with no indirect effect (a1b1 = 0.08, 95% CI [−.03, .17]). Conversely, parent self-oriented perfectionism and fear of pain were not related to anxiety with no indirect effect (a2b2 = −0.02, 95% CI [−.07, .03]).

Model 3 (Figure 1) examined catastrophizing as the mediator and youth depression scores as the outcome. Youth and parent self-oriented perfectionism each accounted for 6% of the variance in their respective catastrophizing scores. This model predicted 40% of the variance in youth depression scores, which was explained through significant positive relationships between youth self-oriented perfectionism and depression and youth catastrophizing and depression, a significant negative relationship between parent self-oriented perfectionism and depression, and an indirect effect of youth self-oriented perfectionism through youth catastrophizing (a1b1 = 0.12, 95% CI [.03, .22]). Parent catastrophizing was not related to depression, with no indirect effect (a2b2 = 0.03, 95% CI [−.01, .10]).

Similarly, in model 4 (Figure 1) which included fear of pain as the mediator, youth and parent self-oriented perfectionism contributed to 3% and 6% of their respective fear of pain scores. The model predicted 42% of the variance in youth depression scores, which was positively predicted by youth self-oriented perfectionism and youth fear of pain, and negatively by parent self-oriented perfectionism. Parent fear of pain was not related to youth depression scores, and the indirect effects of youth (a1b1 = 0.06, 95% CI [−.03, .14]) and parent (a2b2 = 0.02, 95% CI [−.02, .07]) self-oriented perfectionism through fear of pain were not significant.1

Hypothesis 2: self-concealment mediating the relationships between youth/parent perfectionism and youth anxiety and depression

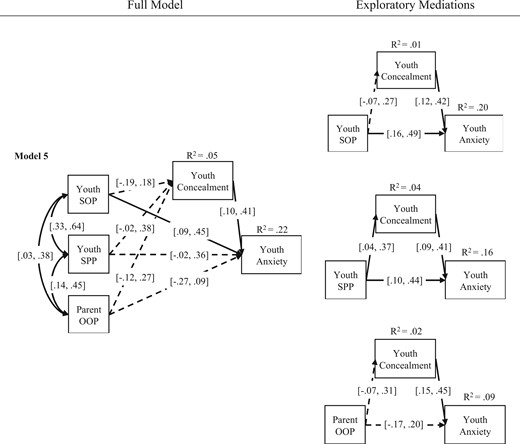

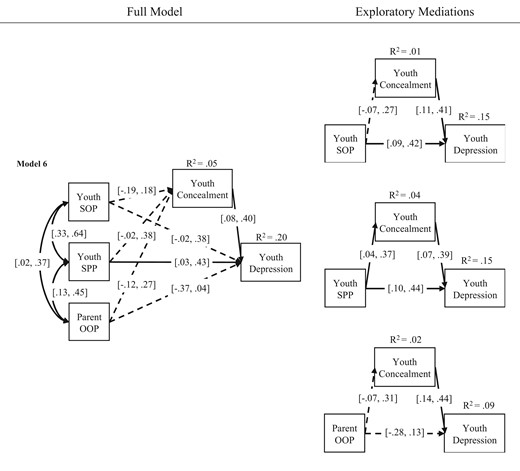

Two path analyses tested the above-mentioned hypothesis with youth anxiety and depression scores as the outcomes. Given the moderately large covariances (βs from .20 to .49) observed between predictors, each model was followed up with exploratory mediations to understand the relationships for each predictor independently, as collinearity might be obscuring interesting patterns in these data.

In model 5 (Figure 2), neither youth self-oriented or socially-prescribed perfectionism, or parent other-oriented perfectionism were significantly related to youth self-concealment when entered in as simultaneous predictors. This model predicted 22% of the variance in youth anxiety; however, only paths from youth self-oriented perfectionism and self-concealment to anxiety were significant. Youth self-oriented, youth socially-prescribed, and parent other-oriented perfectionism did not indirectly contribute (a1b1 = −0.01, 95% CI [−.07, .04]; a2b1 = 0.05, 95% CI [−.01, .11]; a3b1 = 0.02, 95% CI [−.03, .08], respectively). In exploratory mediations, one perfectionism variable was entered at a time. Youth self-concealment remained a significant predictor of anxiety across all models; however, only youth socially-prescribed perfectionism was significantly related to self-concealment. Direct effects were observed for both youth self-oriented and socially-prescribed perfectionism in predicting youth anxiety, and an indirect effect emerged for youth socially-prescribed perfectionism through self-concealment, ab = 0.05, 95% CI [.01, .11]. No other results were significant, including indirect effects for youth self-oriented (ab = .03, 95% CI [−.02, .08]) and parent other-oriented (ab = 0.04, 95% CI [−.02, .10]) perfectionism.

Path analyses for hypothesis 2 and exploratory mediations with each predictor predicting the effects of perfectionism on youth anxiety through self-concealment. Note. The 95% confidence intervals for standardized coefficients are reported. Solid lines represent p < .05. Arrows pointing toward the factor represent residual variance. OOP, Other-Oriented Perfectionism; SOP, Self-Oriented Perfectionism; SPP, Socially-Prescribed Perfectionism.

In model 6 (Figure 3), the same patterns were observed. While perfectionism accounted for 5% of the variance in youth self-concealment, and the model predicted 20% of the variance in youth depression, only paths for youth socially-prescribed perfectionism and self-concealment in predicting depression were significant. Youth self-oriented and socially-prescribed perfectionism, and parent other-oriented perfectionism did not indirectly contribute to depression via youth self-concealment (a1b1 = −0.01, 95% CI [−.07, .04]; a2b1 = 0.05, 95% CI [−.01, .11]; a3b1 = 0.02, 95% CI [−.03, .08], respectively). Exploratory mediations confirmed a significant relationship between youth self-concealment and depression in each model, and youth self-oriented perfectionism in predicting depression. Youth socially-prescribed perfectionism directly predicted self-concealment and depression, and indirectly predicted depression through self-concealment (ab = 0.05, 95% CI [.004, .11]). No other significant pathways emerged, including indirect effects with youth self-oriented (ab = 0.03, 95% CI [−.02, .08]) and parent other-oriented (ab = 0.04, 95% CI [−.02, .11]) perfectionism as predictors.

Path analyses for hypothesis 2 and exploratory mediations with each predictor predicting the effects of perfectionism on youth depression through self-concealment. Note. The 95% confidence intervals for standardized coefficients are reported. Solid lines represent p < .05. Arrows pointing toward the factor represent residual variance. OOP, Other-Oriented Perfectionism; SOP, Self-Oriented Perfectionism; SPP, Socially-Prescribed Perfectionism.

Discussion

Given the rates of internalizing symptoms in youth with JIA, finding ways to reduce them is of utmost importance. To date, only some disease-specific risk factors have been identified (e.g., disease activity, disease burden, pain; see Fair et al., 2019). Perfectionism is a known risk factor for internalizing symptoms in healthy youth (Morris & Lomax, 2014) theorized to be associated with pain (Randall et al., 2018a).

In hypothesis 1, youth and parent self-oriented perfectionism were related (as expected based on the social learning model; Smith et al., 2022); moreover, they were associated with more negative self-evaluations (i.e., pain-related fears and catastrophic thoughts) in youth and parents. As hypothesized, greater self-oriented perfectionism in youth predicted more internalizing symptoms (in part explained through more catastrophic thoughts about their pain). Put simply, youth with JIA who have high expectations for themselves appear to engage in more catastrophic thoughts about their pain (i.e., maladaptive coping responses), which in part contributes to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Interestingly, when parents identified having high expectations for themselves, their children tended to endorse fewer symptoms of depression, although this was not explained through negative self-evaluations.

The findings observed for youth are in keeping with the broader literature. The relationships between self-oriented perfectionism, pain catastrophizing, and fear of pain have been seen in youth with chronic pain (Randall et al., 2018b), and the relationships between dimensions of self-oriented perfectionism and internalizing symptoms have been seen in both youth with IBD (Piercy et al., 2020) and nonclinical samples (Hewitt et al., 2002). The novel finding that youth self-oriented perfectionism predicted internalizing symptoms in youth with JIA, in part through pain catastrophizing, suggests some support for the SCCAMPI model (i.e., that perfectionism may increase negative self-evaluations), and importantly a mechanism through which youth self-oriented perfectionism may contribute to internalizing symptoms in youth with JIA. Although both catastrophizing and fear of pain were used to capture the construct of negative self-evaluations, the lack of indirect effect observed for the latter may suggest that its assessment of fears may involve less of an evaluative component, thus serving as a weaker proxy variable. These findings are critical when considering treatments, as it may be important to target the precipitating factors for anxiety and depression (i.e., perfectionism and catastrophic thoughts) to maintain gains.

The relationships observed between parent self-oriented perfectionism and pain catastrophizing have also been seen in other studies (Randall et al., 2018b), as have the mixed relationships between parent self-oriented perfectionism and youth internalizing symptoms (Cook & Kearney, 2009; Piercy et al., 2020) (i.e., these positive relationships tend to be weaker and less robust in complex analyses). The negative relationship between parent self-oriented perfectionism and youth depression was an intriguing finding. It may be that parents with high standards (for themselves) and/or anxious thoughts pertaining to meeting their child’s physical and psychosocial needs protects against the symptoms of depression that youth with JIA may experience. Finally, although the hypothesized indirect effects of parent self-oriented perfectionism on youth internalizing symptoms through pain-related fears and catastrophizing were not supported, it is possible that other unmeasured mediators may be relevant (e.g., adolescent perceived pressure from parents; Randall et al., 2015), or that parent perfectionism may effect youth in unique ways (e.g., the SCCAMPI model is not inherently dyadic and was developed based on adult health literature without regard for parents’ contributions). Future research might explore how models of perfectionism in the contexts of illness (Molnar et al., 2016) and development (Affrunti & Woodruff-Borden, 2014) can be combined to better explain perfectionism in pediatric populations.

Hypothesis 2 explored the roles of youth self-oriented and socially-prescribed perfectionism and parent other-oriented perfectionism in predicting youth anxiety and depression through increased youth self-concealment. Put simply, we found that youth who perceive that others expect perfection of them are more likely to conceal their symptoms which ultimately contributes to more anxious thoughts and symptoms of low mood. This is consistent with a recent qualitative study demonstrating the presence of pain-related stigma and concealment in JIA populations (Wakefield et al., 2023). Similar results have been observed in healthy adults (Williams & Cropley, 2014) and are consistent with longitudinal research on university students showing that perfectionistic concerns (akin to socially-prescribed perfectionism) led to increased efforts to present oneself as perfect, rather than the reverse (Mackinnon & Sherry, 2012). Comparatively, youth high in self-oriented perfectionism may not experience that same pressure to conceal their imperfections, and youth with parents high in other-oriented perfectionism may not perceive their parents’ perfectionism as targeted toward them (questions assessing other-oriented perfectionism in our study may have benefited from being adapted to target the dyad member in question; Mackinnon et al., 2012). Clinically, if the youth’s perception that others expect perfection of them is not assessed or addressed, it may have undue influences on treatment efficacy.

Together, these findings support the consideration of youth and parent perfectionism in understanding the internalizing symptoms of youth with JIA, particularly when pain catastrophizing and self-concealment are observed. While clients may cling to unhealthy perfectionistic thoughts and behaviors in the belief that it helps them achieve excellence and convey perfection, treatments aim to retain the striving aspects of perfectionism while challenging the need for absolute perfection (Gaudreau, 2019). Galloway et al. (2022) conducted a meta-analysis of 15 randomized-controlled trials comparing control groups to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for perfectionism (i.e.,, targeting cognitive and behavioral factors that maintain perfectionism such as cognitive distortions, performance checking, avoidance, and self-criticism). Although the sample was predominantly adults, CBT for perfectionism was found to be helpful in reducing perfectionism, depression, and anxiety. Not only does CBT for perfectionism appear to be a valuable transdiagnostic treatment that targets internalizing symptoms, if left out it may dampen the effects of prevention and treatment efforts. Although further research is warranted particularly for pediatric pain populations (Randall et al., 2018a), directly assessing for and targeting trait perfectionism, alongside other concerns such as pain, may be beneficial (Flett & Hewitt, 2014; Morris & Lomax, 2014; Randall et al., 2018a).

The strengths of this study include the exploration of a relatively novel risk factor both in the pediatric pain and JIA literatures, the use of parent/youth data, preregistration of a priori hypotheses, open data, and the exploration of the mechanisms by which perfectionism impacts youth internalizing symptoms. Limitations include the use of partial data (e.g., reliance on statistical methods to supplement missing data), self-report data (e.g., one may not know their disease characteristics or diagnosis), and the use of an Internet survey design (e.g., attrition, potential sampling bias, threats to data validity). Given the challenges with recruitment, the sample size was lower than anticipated, potentially limiting the ability to detect significance for the parent pathways and limiting our ability to include covariates. Future research should explore if the pattern of results differs by potentially relevant covariates (e.g., sex, age, ethnicity, socio-economic status, disease status). The use of proxy measures to assess “negative self-evaluations” (i.e., pain catastrophizing and fear of pain) is also a limitation. In the absence of a better measure, however, both constructs may be interpreted as a negative self-evaluation, given the maladaptive and intrusive cognitions and fears about pain involved. Finally, the limitations of cross-sectional mediation models are well-known and include problems such as lack of temporal precedence and third variable confounding. Though our model makes assumptions about the directionality of relationships based on theory, readers are cautioned to avoid making strong causal inferences based on these data (just as they should with any correlational study) until large-sample longitudinal research with covariate adjustment can be conducted.

In addition to overcoming the above-mentioned limitations, further exploration of the SCCAMPI is also warranted (e.g., application to pediatric populations, assessing other pathways of perceived control and social support, measurement of other mediators such as coping and stress, measurement of other outcomes such as pain and functioning).

In conclusion, this observational study identified relationships between youth and parent perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety and depression in youth with JIA. Youth who demonstrate a self-imposed pursuit of high standards and youth who perceive that others expect perfection of them appear to be especially at risk, as they are more likely to think about their pain in catastrophic ways and conceal their symptoms, respectively. While future research would benefit from further exploring these relationships with larger samples and longitudinal designs, screening for perfectionistic tendencies in youth with JIA and their parents may be beneficial, particularly when pain catastrophizing and self-concealment are observed. Clinicians working with youth with JIA and their families may consider treating underlying perfectionism alongside other presenting mental health concerns.

Footnotes

Partner effects were explored between the predictors and mediators in each of these models, though these paths were not preregistered. None of these pathways were significant.

Author contributions

Yvonne Brandelli (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [lead], Formal analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [lead], Resources [equal], Software [equal], Validation [equal], Visualization [equal], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Sean Mackinnon (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [supporting], Formal analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [supporting], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [supporting], Resources [equal], Software [equal], Supervision [equal], Validation [equal], Visualization [equal], Writing—original draft [supporting], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Christine T. Chambers (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [supporting], Formal analysis [supporting], Funding acquisition [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [supporting], Resources [equal], Software [equal], Supervision [equal], Validation [equal], Visualization [equal], Writing—original draft [supporting], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Jennifer Parker (Conceptualization [supporting], Data curation [supporting], Formal analysis [supporting], Funding acquisition [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Project administration [supporting], Resources [supporting], Software [supporting], Validation [supporting], Visualization [supporting], Writing—original draft [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Adam Huber (Conceptualization [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Jennifer N. Stinson (Conceptualization [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), Shannon Johnson (Conceptualization [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting]), and Jennifer Wilson (Conceptualization [supporting], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Writing—review & editing [supporting])

Funding

This work was supported by salary support provided to Y.N.B. through a Scotia Scholars award from Research Nova Scotia, a Nova Scotia Research and Innovation Graduate Scholarship, the Dr Mabel E. Goudge Award from the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at Dalhousie University, and a Graduate Studentship from IWK Health. Y.N.B. is also a trainee member of Pain in Child Health, a Strategic Training Initiative. C.T.C. and S.P.M. are senior authors. C.T.C. is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair. Her research is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN 167902) and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. The funders did not play a role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation, or reporting of these data.

Conflicts of interest: The pre-review version of this manuscript was included in the PhD dissertation of Y.N.B., accessible at https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/items/41ad2854-ced6-4353-9ab2-dd8a573c1e48.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Isabel Jordan for helping to create a patient partnership plan for this research and Brittany Cormier for supporting participant recruitment. We are grateful for the contributions of Cassie and Friends, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the pediatric rheumatology community, for their partnership in this work. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Tiffany Thompson, Abby Mazzone, and Amy Mazzone, patient and family partners who have been instrumental in the study design, execution, and interpretation. We would like to acknowledge the IWK Health’s rheumatology clinic and staff, as well as the numerous arthritis organizations, industry partners, parent-groups, and individuals who have helped to share the recruitment call-outs for this study. Last, but not least, we would like to thank all of those who took part in this research.