-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Cara M Hoffart, Dustin P Wallace, Diagnosis Does Not Automatically Remove Stigma for Young People with Invisible Illness, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 48, Issue 4, April 2023, Pages 352–355, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsad010

Close - Share Icon Share

Thank you for the invitation to comment on this interesting and important paper. As a pediatric rheumatologist and a pediatric psychologist, we meet many young people affected by invisible illnesses including juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), amplified pain syndromes (APS), hypermobility-related conditions, and dysautonomia, among others. Wakefield et al. (2023) evaluated the experience of pain-related stigma in young people with JIA and their findings reveal several assumptions often made by the medical community which bear further discussion. We explore reasons the medical community may perceive that diagnosis “validates” symptoms and yet this may not affect a young person’s experience of stigma from their social environment. Further, recent research suggests that even for a well-understood pain-related pathophysiology like inflammatory pain in JIA, pain is an important treatment target and may not correlate as directly with disease activity as expected. Finally, we suggest that for young people experiencing painful invisible illness, lessons learned from the treatment of idiopathic chronic pain may provide support that minimizes impairment from symptoms and may even help the symptoms.

Diagnosis Does Not Make Invisible Illness Visible

Medical providers experience confusion and distress when working with a patient with unexplained symptoms, and the patients often have a similar experience. In the case of JIA, symptoms might present with higher pain intensity while others may have an insidious onset with little pain and more stiffness (Rashid et al., 2018). Evaluation leading to diagnosis can be slow and frustrating for patients and their families, as a JIA diagnosis requires arthritis symptoms for at least 6 weeks and it can take much longer than that to find a physician who is able to diagnose this condition (Foster & Rapley, 2010). Children with JIA, just like those with primary pain conditions, often feel unheard, invalidated, and dismissed by medical providers while awaiting a diagnosis (Wakefield et al., 2023).

Once diagnosed, medical providers’ and patients’ experiences may differ. Indeed, the medical community often assumes that having a “concrete” diagnosis will resolve many social impacts of a health issue; however, Wakefield and colleagues’ results challenge some of those assumptions. These young people with JIA continued to perceive considerable stigma related to pain and the diagnosis itself (Wakefield et al., 2023), which aligns with our own experiences. Like those with primary pain conditions, children with JIA often feel they are battling “invisible” disease. Wakefield and colleagues identify an important stigma-related theme of ageism, as a common response when an adult or peer learns of a new diagnosis of JIA is “I didn’t know kids could get arthritis.” This can be invalidating and embarrassing for a young person to hear, and this reply underscores a more general lack of knowledge about arthritis. This lack of understanding from peers and authority figures such as teachers and coaches may lead those with JIA to experience stigma leading to concealment (Tong et al., 2012).

Pain from Arthritis and Other Conditions Can Develop Nociplastic Features

Primary pain conditions are increasingly labeled as nociplastic in nature (sometimes called central sensitization and/or amplified pain), which describes pain related to changes in the function of the peripheral and central nervous system but without evidence of damage or degeneration (Nijs et al., 2021). On the other hand, pain in individuals with JIA and other inflammatory conditions is assumed to be an indicator of active disease and the need for treatment (i.e., nociceptive). New research is increasingly questioning that assumption, with laboratory models demonstrating that pain can persist for weeks to months even after adequate treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune mechanisms (De Lalouvière et al., 2014; La Hausse et al, 2021).

This suggests that nociplastic changes, peripherally and/or centrally, may be a contributor to ongoing pain more broadly than previously recognized. Importantly, other research has shown that pain in children with JIA may be a stronger contributor to disability than progression of the disease itself (De Lalouvière et al., 2014; Oskarsdottir et al., 2022). Thus, full treatment of JIA should certainly address inflammation, at the same time proactively addressing the potential for nociplastic changes to the nervous system as a consequence of disease-related pain. Otherwise, families and medical providers may limit activities based upon the belief that pain indicates continued disease activity when in fact autoimmune activity may be well controlled and they are instead awaiting improvements in the nociplastic consequences of past disease activity.

A General Framework for Supporting Youth with Painful Invisible Illnesses

Thus, for youth with any invisible illness, it remains important for medical providers to monitor disease activity via examination, labs, and imaging (as relevant and appropriate) to determine changes to immunotherapy or other disease-modifying treatment. At the same time, youth and families with conditions that cause pain should be educated about the potential for nociplastic nerve changes causing continued pain (e.g., Brainman video “understanding pain in less than 5 min”:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5KrUL8tOaQs; or pain education from “Tame the Beast”, a patient-directed resource for individuals living with chronic pain, created by pain scientists: https://www.tamethebeast.org/), along with other disease-specific education that is provided. When doing this, it is important to validate the pain experience and to avoid messaging that implies pain is “all in their head,” which can result in distrust and medical trauma.

One avenue to address perceived stigma is by fostering communities with others who understand. This can occur through experiences that allow individuals with a certain health-challenge to meet others facing similar struggles, which can encourage functioning and self-management (Stenberg et al., 2022) and receiving support may lead to a desire to support others (Saint & Heisler, 2023). To help foster this kind of community for young people, our institution helps the Arthritis Foundation facilitate an annual camp for youth with JIA (https://www.arthritis.org/events/ja-camps). For parents, our organization offers a “parents offering parents support” (POPS) program where parents are trained to provide support and mentorship to another parent of a child experiencing a similar condition (https://www.childrensmercy.org/your-visit/family-support-and-resources/support-groups-and-programs/pops/). Rare diagnoses, especially when accompanied by chronic pain can result in isolation, fear of disbelief in the diagnosis from others, which can even lead to self-doubt. These programs foster friendships and community, and social contact with those who have shared experiences in a coordinated environment can be empowering.

Another avenue to address stigma is through broadening awareness at the community level. Wakefield et al. (2023) advise antistigma interventions that provide social contact with individuals from a stigmatized population. We have seen such programs create parental and child support through local and national foundations dedicated to providing education, awareness, mentorship, and support groups. At our institution, physicians, nurses, social workers, and psychologists work with local and national organizations to develop and implement both parent and child education about JIA and associated symptoms and potential family concerns. Not only do these programs benefit the community and people facing invisible illness, but we have observed our providers gain better understanding of the struggle associated with diagnosis, and language to show understanding when working with individuals with invisible illness.

Wakefield et al. (2023) also recommend referral to psychology or the presence of a co-located psychologist, which can help address stress, anxiety, mood changes, academic impacts, and other challenges due to a chronic health condition. Psychologists may also help a patient develop a “script” to quickly explain about their health and treatment at the level they wish. However, there are not enough providers to provide direct intervention with all families! To provide optimal support to as many families as possible, psychologists should partner with social work, nursing, and medical providers to create materials that support children with JIA and primary pain conditions in their environments. This might include specific coping plans for tough days, templates for developing a script to explain diagnosis, and standard recommendations for the academic setting. Indeed, basic information can help schools develop appropriate accommodations and can also educate teachers, school counselors and coaches. Of note, the Society of Pediatric Psychology Pain Special Interest Group has created multiple resources about living with a painful chronic condition, managing school, coping with mental health consequences, and these can be used by medical teams and sometimes given directly to families (https://pedpsych.org/sigs/pain/). Together these supports can reduce a young person’s distress when facing ignorance or invalidation at school and other social settings.

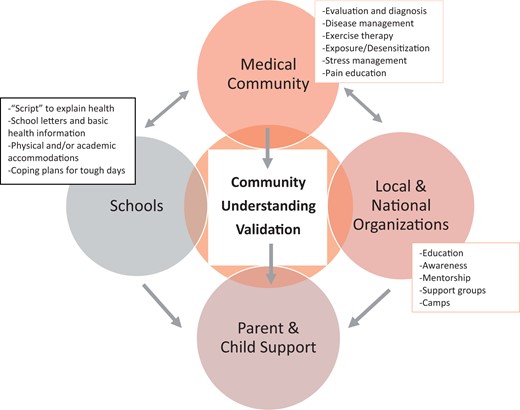

Finally, along with education about arthritis and its treatment, families should be given recommendations to proactively reduce the potential for nociplastic changes. A developing line of research from basic and applied sciences demonstrate that exercise, stress management, and exposure to feared symptoms in a safe manner (desensitization) lead to improved functioning and fewer symptoms over time (Eller et al., 2021; Hoffart & Wallace, 2014). In our clinical practice, we have found that it is critical for medical providers to clearly indicate what kinds of symptoms might be “dangerous” (e.g., pushing through may cause injury or damage) as compared to other symptoms which might be equally intense, but which do not indicate one should stop an activity. After understanding this, many youth feel confident not allowing symptoms to be decision-maker for their activities, while still remaining safe. Taken together, these ideas help the medical community better address pain and stigma through direct care, through coordination with schools and outside organizations, and this creates wraparound supports for youth with arthritis (see Figure 1).

Wraparound supports for youth with arthritis or other painful invisible illnesses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are differences in the experience of pain-related stigma in individuals with JIA (Wakefield et al., 2023) as compared to those with primary chronic pain conditions (e.g., Wakefield et al., 2022). However, there are more similarities than previously assumed, and the medical system’s bias toward “explanation by diagnosis” may lead to blind spots when interacting with youth who have JIA or similar conditions. As research on the experience of invisible illness evolves, we anticipate additional populations will be identified (e.g., Frye et al., 2022), and we specifically encourage more investigation jointly addressing individuals with different types of invisible illness. This would validate the experience of youth whose diagnosis has an identified pathophysiology and also those for whom the medical understanding of the pathophysiology is evolving. Importantly, this research would allow the field to draw on important common-factor resilience builders such as exercise, stress management, and appropriate exposure when pain-related fear is causing greater impairment than required by medical limitations. Finally, this kind of research is critical to improving the medical community’s awareness about these conditions and how to explain and treat the complex biopsychosocial model that contributes to them.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Data Availability

Additional information available from the authors on request.