-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Julia D Johnston, Jeffrey Schatz, Sarah E Bills, Bridgett G Frye, Gabriela C Carrara, Preschool Pain Management Program for Young Children with Sickle Cell Disease: A Pre–Post Feasibility Study, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 48, Issue 4, April 2023, Pages 330–340, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsac096

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Vaso-occlusive pain crises in sickle cell disease (SCD) often begin in early childhood. We developed an online pain management intervention to teach caregivers of preschool-aged children with SCD behavioral pain management strategies. The feasibility study goals were to examine response to recruitment, barriers to participation, engagement, acceptability and perceived usefulness of the intervention, and suitability of outcome measures.

Caregivers of children aged 2.0–5.9 years with access to text messaging and a device to access online videos were recruited from a Southeastern outpatient hematology clinic for a 12-week intervention consisting of pain management videos. Videos taught caregivers behavioral pain management strategies and adaptive responses to pain. Workbook activities helped tailor strategies to their child. Caregivers completed process measures as well as baseline and follow-up measures of pain catastrophizing (Pain Catastrophizing Scale—Parent Report) and responses to their child’s pain (Adult Response to Children’s Symptoms).

Fifty percent (10 of 20) of eligible parents enrolled. Caregivers partially completed (N = 6), completed (N = 3), or did not engage (N = 1) in the intervention. Caregivers who engaged in the program reported implementing the pain management strategies. The intervention was rated as high quality, relevant, and useful. Measures of pain catastrophizing and responses to their child’s pain appeared sensitive to change.

The intervention to promote adaptive coping to pain was acceptable and feasible for caregivers though we found barriers to delivering the intervention to parents. Evaluation of a modified version of the program is indicated to assess implementation issues and effectiveness.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder affecting around 1 in 365 African American births in the USA (Rees et al., 2010) and characterized by symptoms of anemia, increased risk for infection, and vaso-occlusive pain, among others (Brown, 2006). Of these symptoms, vaso-occlusive pain is the most frequent complication affecting youth. Pain crises begin to occur for youth as early as 4–6 months of age and increase in incidence across development (Benjamin, 2008; Gill et al., 1995). A study of preschool-aged children with SCD revealed that approximately 15% of children 1–6 years of age evidence rates of sickle cell pain equivalent to those seen in older children and adolescents (Dampier et al., 2014). During childhood, patients typically experience one-to-two severe pain crises requiring emergency medical care, with another estimated 10 pain episodes managed at home (Brousseau et al., 2010; Dampier et al., 2002b; Nottage et al., 2013). Despite the frequency with which pain episodes occur in early life, little research to-date has examined pain management in very young children with SCD. Management of pain episodes early in life by parents is an important developmental context for later child and family coping with pain. Frequent and unmanaged pain is associated with increased internalizing symptoms, functional disability, and increased risk for developing chronic pain, which may affect nearly 25% of school-age youth and adolescents with SCD (though strong epidemiological estimates for chronic pain prevalence in youth with SCD remain undetermined; Sil et al., 2016a, 2020). Early intervention and education may prevent these secondary problems as well as improve identification of chronic pain.

The majority of pain crises youth with SCD experience can be managed at home with analgesic and NSAID pain medications (Dampier et al., 2002). A daily diary study of children with SCD less than 6 years of age indicated that parents most often used medication (94% of the time) and comfort in the form of massage or holding the child (64% of the time) to manage their child’s sickle cell pain (Ely et al., 2002). The use of formal behavioral strategies among parents of children with SCD, such as activity pacing, relaxation skills like deep breathing and muscle relaxation, and parent-guided operant strategies, among others, is infrequent and caregivers rarely receive instruction on nonpharmacological pain management from medical providers (Dampier et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2018) despite recent efforts to provision biopsychosocial pain management for sickle cell pain. As such, caregivers likely vary in their understanding of how to use behavioral strategies to manage their child’s pain. While acute nociception is a physiological phenomenon, the subjective experience of pain is influenced by transactional biological, psychological, and social processes (Palermo et al., 2014; Riddell et al., 2013). The strength by which biological, psychological, and social factors influence pain in children changes across their development (Sameroff, 2010). For very young children, the influence of social context is highly salient, and caregivers are responsible for identifying and treating pain as well as regulating the health behaviors, sleep schedules, activity levels, and coping strategies of preschool-aged children (Palermo et al., 2014; Riddell et al., 2013). Encouraging helpful practices among caregivers in their child’s early years should foster adaptive pain coping, which may lead to better functional outcomes in middle childhood and adolescence.

Unhelpful practices that thwart positive adjustment in youth include parent pain catastrophizing and overly solicitous responses to children’s pain (Sil et al., 2016b). Parent pain catastrophizing is characterized by exaggerated appraisals of pain, feelings of helplessness, and ruminative thoughts, and has been consistently associated with negative functional and emotional outcomes among children (Palermo & Chambers, 2005). Overly solicitous responses to child’s pain like excessive comfort, reductions in children’s responsibilities, and special privileges commonly lead to increased sick role behavior and increased functional disability (Palermo & Chambers, 2005; Sil et al., 2016a). Targeting caregiver’s emotional and behavioral responses to their children’s pain is paramount to promoting positive coping among youth. Along these lines, pain management interventions increasing parent’s knowledge of pain and coping, promoting adaptive responses to their child’s pain, and encouraging use of operant strategies have yielded positive psychosocial outcomes among youth aged 7–18 years with pain syndromes (Palermo et al., 2009; Sanders et al., 1994). Among preschool-aged children, caregivers likely play an even greater role in influencing functional outcomes in their children (Palermo et al., 2014; Sameroff, 2010).

Caregivers of youth with SCD have expressed a desire for family-centered interventions and pain management education (Mitchell et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2018). Given the myriad demands associated with parenting a young child with SCD, including managing medications, medical complications, and attending medical appointments (Atkin & Ahmad, 2000; Burnes et al., 2008), caregivers would likely benefit most from flexible and easily accessible pain management education. Electronically delivered interventions have addressed numerous barriers typically preventing patients and caregivers from engaging in in-person pain management programs (Badawy et al., 2018; Schatz et al., 2015). eHealth pain management interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing pain intensity, reducing activity limitations, and increasing coping among youth with SCD and other pain-related conditions (Palermo et al., 2009, 2016; Schatz et al., 2015). Online or eHealth intervention programs also hold potential to reach a greater number of parents. As such, an electronically delivered pain management intervention may be most feasible and subsequently effective for caregivers of preschool-aged children with SCD. Because caregivers are primarily responsible for identifying and managing the pain of their preschool-aged child, an intervention geared toward parent training is most appropriate. As such, authors developed an eHealth pain intervention to support needs of preschool-aged children with SCD.

We elected to conduct a feasibility study of our intervention given the novelty of this intervention for pain in SCD and the historical complexity achieving successful recruitment for studies of SCD (Peters-Lawrence et al., 2012). In our local catchment area >90% of youth born with SCD are seen regularly at a single hematology care center and this center was chosen as the logical recruitment point that provided largest access to parents of preschoolers with SCD. The present study examines response to recruitment, barriers to participation, engagement, acceptability and perceived usefulness of the intervention, and suitability of outcome measures. Based on a prior survey of the target group, we anticipated 59% (95% CI: 44%–73%) of parents would be interested in the intervention (Smith et al., 2018). Goals for engagement were somewhat difficult to determine but we noted in a similarly structured intervention involving parenting strategies taught through videos, workbooks, and phone support that 47% (95% CI: 35%–59%) of parents completed the intervention, 47% (95% CI: 35%–59%) partially completed the intervention, and 6% (95% CI: 0%–15%) dropped out before receiving any intervention (Day & Sanders, 2018). These data were used as points of comparison for the current study.

Methods

Participants

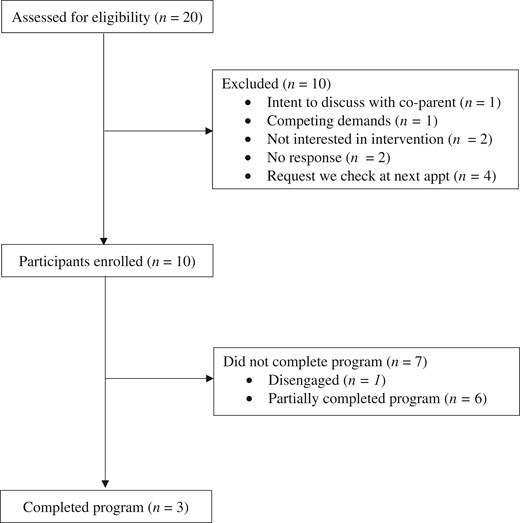

Twenty consecutive caregivers of children diagnosed with SCD between the ages of 2 years 0 months and 5 years 11 months were approached through a local comprehensive sickle cell clinic in the Southeastern USA (Figure 1). The clinic annually treats more than 90% of all youth with SCD in the catchment area. This target number was selected based on total number of preschool-aged children treated at the clinic, time restrictions for data collection, and the relatively rare nature of SCD.

Participant flow diagram. Note. Reasons for exclusion are not mutually exclusive.

Procedures

This pre–post feasibility study was not registered as a pilot study. After obtaining approval from the medical center Institutional Review Board, caregivers with children between ages of 2 and 6 were identified via chart review by an investigator. Caregivers identified via chart review with a preschool-aged child 2.0–5.9 years in age were approached before or after their child’s routine medical appointment by a study investigator (either a doctoral-level psychology student or faculty psychologist). Eligible caregivers were those with a child within the target age range, a phone capable of texting, regular access to WIFI/Internet, and regular access to an electronic device capable of playing videos (e.g., smartphone, iPad, tablet, computer).

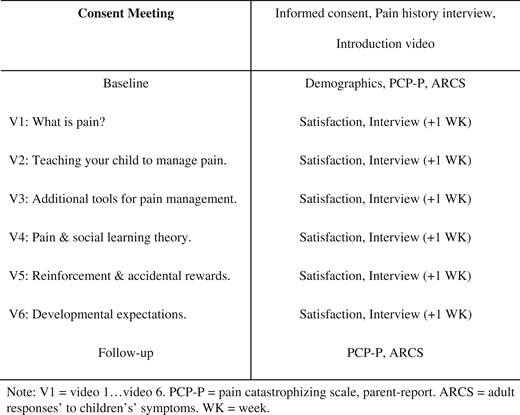

Eligible parents completed informed consent procedures, the Structured Pain Interview, watched a 3-min introduction video about the program, and completed the paired activities in their pain management workbook (e.g., “What are some things that you hope to learn from these videos?”). Caregivers were provided with an overview and timeline of the intervention, which was designed to be completed over 6–12 weeks to provide flexibility in the rate of completion. The intervention was completed remotely and videos were accessed on a private YouTube platform (Figure 2). Baseline measures were completed online through a link sent via e-mail. After completing baseline measures, caregivers were sent a link that would permit them to access the first pain management video and texted researchers upon finishing this video. After researchers were notified via text that a participant had finished watching a video, two steps occurred. First, an online satisfaction survey was sent to participants via e-mail to (a) assess acceptability and (b) confirm participants watched the video. Second, researchers communicated with participants via text to schedule the follow-up interview. Interviews, which were conducted via phone, were scheduled 1 week after participants had finished watching a video. This 1-week delay was designed to allow caregivers to practice strategies learned from the intervention and to increase the chances that caregivers would have a chance to practice strategies in the context of a pain crisis. Follow-up phone interviews were completed by the PI or trained research assistants to ensure caregivers were accessing the intervention, assess implementation of behavioral pain management skills, and communicate any other concerns about study participation (e.g., potential adverse events). Alternative methods (e.g., daily diaries) were not utilized given the infrequency of pain crises in preschool-aged children and to reduce participant burden. If caregivers had not notified researchers via text, reminder texts were sent. Researchers called participants after 1 week if contact had not been established. After completing the online satisfaction survey and follow-up interview, caregivers received access to the next pain management video in the intervention via e-mail and completed process measures including the online satisfaction survey and follow-up interview. After watching all videos and process measures, participants completed online outcome measures. Participants were compensated with gift cards for completing baseline measures ($10.00), satisfaction surveys ($5.00), phone interviews ($5.00), and follow-up measures ($10.00).

Pain Management Curriculum

The eHealth intervention consisted of six pain management videos designed to teach caregivers information about sickle cell pain, behavioral pain management strategies, adaptive responses to youth’s pain, and changes in pain management across preschool development. Videos were between 9 and 15 min long. Video length was determined by the intervention curriculum and feedback from three researchers after pilot testing videos. Content delivered in this intervention was primarily developed by the second author and informed by a prior needs assessment conducted at the clinic (Smith et al., 2018) and evidence-based interventions for pain management with attention to developmental factors (Palermo et al., 2014). Strategies from existing cognitive behavioral therapies for school-age and adolescent youth with chronic or recurrent pain syndromes were adapted for preschool-aged children and included psychoeducation, relaxation skills training, and others (Palermo, 2012; Schatz et al., 2015). The intervention videos included the following content: (a) psychoeducation about pain (e.g., gate control theory of pain), sickle cell pain specifically, and medical treatments used to reduce pain symptoms, (b) information for how parents could teach their children to use strategies like deep breathing, activity pacing, pleasant activity scheduling, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery, (c) review of biomedical strategies for pain management, (d) social learning theory applied to pain management and adaptive responses to youth’s pain, (e) using positive reinforcement and avoiding accidental rewards to increase positive coping behaviors and eliminate sick role behavior, (f) scaffolding pain coping and encouraging self-management behaviors as children develop from age 2 to 6 years. Workbook activities were paired with the introduction video as well as videos 2–6 to help parents tailor pain management strategies to their child’s specific needs and preferences. Examples of workbook activities are as follows: “write down ideas you have of things that usually hold your child’s attention for longer periods of time, like drawing or playing with Legos,” “Think about things your child does over the course of a normal day. Can you think of ways that these could be done a little bit at a time or be done differently if your child’s arm or leg was hurting,” “What are some behaviors that you try to reward your child for doing?”. These activities aligned with study goals of encouraging use of behavioral pain management strategies specific to youth’s preferences. The workbook was also designed such that the finished product could be a tailored reference book for caregivers that included tools, questions for their child’s medical provider, and pain management strategies. Parents were provided with an electronic PDF pain management resource guide in which some content from the intervention was printed (e.g., deep breathing, activity pacing) and additional resources (e.g., pain management books, YouTube videos) were referenced.

Measures

Caregivers completed descriptive measures including a demographic questionnaire containing questions assessing basic background information of participants (Table I). At the consent meeting, guardians completed the Structured Pain Interview, a modified version of the Structured Pain Interview created by Gil et al. (1989). The questionnaire assesses information about the participants’ child’s pain history, including number of pain episodes in the previous year, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations. Caregivers completed secondary pre- and post-intervention measures including the Pain Catastrophizing Scale—Parent Report (PCS-P), a 13-item scale that measures the extent to which parents ruminate, magnify, and feel helpless about their child’s pain. This scale has shown good reliability with internal consistencies ranging between .81 and .93 (Goubert et al., 2006). They also completed a modified version of the Adult Response to Children’s Symptoms (ARCS), a 29-item measure with subscales assessing protective caretaking behaviors (protectiveness), critical responses to pain behavior (minimizing), and generally encouraging (monitoring/encouraging) responses to children’s pain behavior using the original 3-factor structure of the ARCS. This scale has shown good validity and adequate reliability [Cronbach’s α = .87 (protect), .67 (minimize), .79 (encourage/monitor)] among parents of children aged 8–18 years (Van Slyke & Walker, 2006). Six items (5, 7, 11, 13, 16, 29) were dropped from the ARCS for the present study to address potential content validity issues for using the scale with preschoolers who have SCD. Two items were dropped due to age relevance (e.g., let your child stay home from school, tell your child that he/she does not have to finish all of their homework). Three items were dropped to eliminate potential bias in the scale when used with patients with SCD, for whom pain medication, hydration, and communicating with the clinic are commonly part of the home pain management plans provided to parents by our medical staff (e.g., give your child some medicine, get your child something to eat or drink, call the doctor or take your child to the doctor?). Finally, one item was dropped due to significant content overlap with other items on the scale (e.g., give your child special privileges).

| Variables . | Caregivers . | Child . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) . | (n = 10) . | |

| Age in years (M, SD) | 3.9, X.XX | |

| Gender (N) | ||

| Female | 8 (80%) | 3 (30%) |

| Male | 2 (20%) | 7 (70%) |

| Race (N) | ||

| African-American/Black | 10 (100%) | 10 (100%) |

| Caregiver type (N) | ||

| Biological parent | 8 (80%) | – |

| Legal guardian | 1 (10%) | – |

| Grandparent | 1 (10%) | – |

| Sickle cell genotype | ||

| HbSS | – | 7 (70%) |

| HbSC | – | 2 (20%) |

| HbSβ+ thalassemia | – | 1 (10%) |

| Pain episodes during prior year (4+ h in length), parent report (M, SD) | 1.70, 1.89 | |

| Resulting in admission or ER visit | 1.40, 1.51 | |

| Managed as an outpatient | 0.30, 0.67 |

| Variables . | Caregivers . | Child . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) . | (n = 10) . | |

| Age in years (M, SD) | 3.9, X.XX | |

| Gender (N) | ||

| Female | 8 (80%) | 3 (30%) |

| Male | 2 (20%) | 7 (70%) |

| Race (N) | ||

| African-American/Black | 10 (100%) | 10 (100%) |

| Caregiver type (N) | ||

| Biological parent | 8 (80%) | – |

| Legal guardian | 1 (10%) | – |

| Grandparent | 1 (10%) | – |

| Sickle cell genotype | ||

| HbSS | – | 7 (70%) |

| HbSC | – | 2 (20%) |

| HbSβ+ thalassemia | – | 1 (10%) |

| Pain episodes during prior year (4+ h in length), parent report (M, SD) | 1.70, 1.89 | |

| Resulting in admission or ER visit | 1.40, 1.51 | |

| Managed as an outpatient | 0.30, 0.67 |

Note. ER = emergency room.

| Variables . | Caregivers . | Child . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) . | (n = 10) . | |

| Age in years (M, SD) | 3.9, X.XX | |

| Gender (N) | ||

| Female | 8 (80%) | 3 (30%) |

| Male | 2 (20%) | 7 (70%) |

| Race (N) | ||

| African-American/Black | 10 (100%) | 10 (100%) |

| Caregiver type (N) | ||

| Biological parent | 8 (80%) | – |

| Legal guardian | 1 (10%) | – |

| Grandparent | 1 (10%) | – |

| Sickle cell genotype | ||

| HbSS | – | 7 (70%) |

| HbSC | – | 2 (20%) |

| HbSβ+ thalassemia | – | 1 (10%) |

| Pain episodes during prior year (4+ h in length), parent report (M, SD) | 1.70, 1.89 | |

| Resulting in admission or ER visit | 1.40, 1.51 | |

| Managed as an outpatient | 0.30, 0.67 |

| Variables . | Caregivers . | Child . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) . | (n = 10) . | |

| Age in years (M, SD) | 3.9, X.XX | |

| Gender (N) | ||

| Female | 8 (80%) | 3 (30%) |

| Male | 2 (20%) | 7 (70%) |

| Race (N) | ||

| African-American/Black | 10 (100%) | 10 (100%) |

| Caregiver type (N) | ||

| Biological parent | 8 (80%) | – |

| Legal guardian | 1 (10%) | – |

| Grandparent | 1 (10%) | – |

| Sickle cell genotype | ||

| HbSS | – | 7 (70%) |

| HbSC | – | 2 (20%) |

| HbSβ+ thalassemia | – | 1 (10%) |

| Pain episodes during prior year (4+ h in length), parent report (M, SD) | 1.70, 1.89 | |

| Resulting in admission or ER visit | 1.40, 1.51 | |

| Managed as an outpatient | 0.30, 0.67 |

Note. ER = emergency room.

Caregivers completed primary measures of acceptability and use of skills after viewing each video. Guardians completed an acceptability survey consisting of eight items assessing the degree to which participants were satisfied with qualities (e.g., visual, audio, ease of understanding, relevance, utility) of the pain management videos rated on a 5-item Likert scale varying from a negative to positive appraisal. The implementation measure contained three items regarding use and perceived utility of specific pain management strategies rated on a similar 4-item Likert scale, one item about child pain since last contact and six items that were asked if the caregiver reported that their child had experienced a pain crisis since last speaking with researchers. These optional questions assessed use of pain management strategies for the child’s pain episode. Data available upon request.

Planned analyses

Response to recruitment, engagement, acceptability, and perceived usefulness data were quantified by generating frequencies via pooled participant data. Barriers to recruitment and engagement were described qualitatively. To assess for the suitability of the pre–post measures, we examined changes in scores for parent pain catastrophizing and responses to youth’s pain as pre–post mean differences; we computed Reliable Change (RC) criteria scores using a 95% criterion and deriving alpha reliability coefficients and standard deviation values from prior studies (Christensen & Mendoza, 1986; Goubert et al., 2006; Van Slyke & Walker, 2006).

Results

Twenty caregivers were approached to assess eligibility and interest from August 2019 through February 2022. Of these participants, all were eligible with 10 declining to enroll at the time of meeting and 10 enrolling in the study (50% recruitment of eligible participants). Reasons for declining are as follows: requesting to speak with other caregiver about the intervention (N = 1), pain was not yet a problem for their child (N = 1), too many competing demands (N = 1), not interested in the intervention (N = 2), the caregiver could not meet with the research team and requested they check back in with them at their next appointment (N = 4), did not meet inclusion criteria (N = 1), and no response (N = 2) (reasons provided are not mutually exclusive).

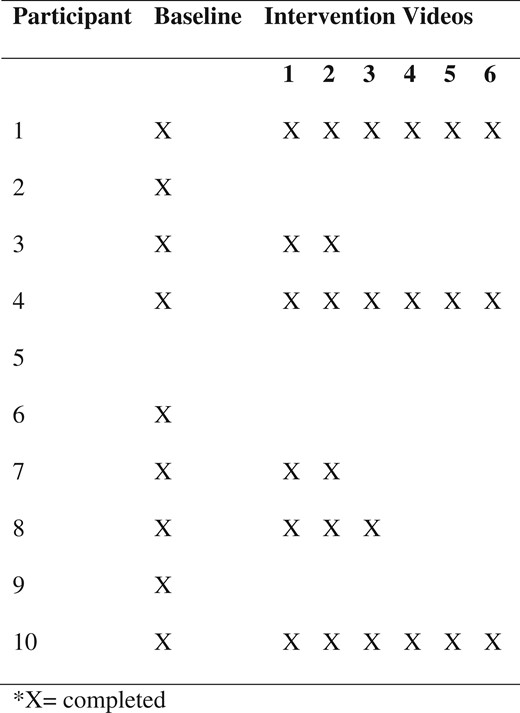

Three phenotypes of engagement in terms of usage of the intervention emerged among intervention participants: completers (N = 3; 30%), partial completers (N = 6; 60%), and disengaged participants (N = 1; 10%) (Figure 3). Completers were caregivers who participated in the intervention as it was designed (e.g., watched all videos and completed all measures). Of note, two completers finished the intervention within 12 weeks; however, one of the three completers took 18 weeks to complete the intervention. Additional time was afforded to this family due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which emerged during their participation, and the parent reported transient pandemic-related obstacles to participation. Partial completers were caregivers who completed the introductory video and baseline measures (N = 3) and those who watched some intervention videos (N = 3). Partial completers watched one (N = 1), two (N = 1), and three (N = 1) videos. The disengaged caregiver did not complete baseline measures or watch any videos from the intervention. Follow-up conversations via phone and in the clinic identified the following barriers as contributing to partial engagement or disengagement: difficulties accessing internet/WiFi, inability to access YouTube videos that could not be resolved with technical support, competing demands for caregivers (e.g., birth of a new child), and the COVID-19 pandemic. Of note, research assistants were available to help families resolve technical difficulties via phone, e-mail, and text. Most technical difficulties reported by families were resolved with support; however, one caregiver was not able to access the intervention videos on her phone, which accounted for disengagement from one participant. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic emerged during the intervention. Additional flexibility was afforded to families (e.g., extra time, more frequent check-ins) to allow completion despite the pandemic; however, the interventionists stopped data collection in June 2020 due to the remaining participants being unresponsive to follow-up contacts and length of time elapsed in the intervention. It is unclear exactly how the onset of the pandemic affected families and their engagement with the intervention as these data were not systematically collected. No study-related adverse events (e.g., problems resulting from use of behavioral strategies) were reported by caregivers. Caregivers were permitted access the intervention materials after data collection ended.

Caregivers completed acceptability surveys after each video. A total of 23 survey responses were collected. There did not appear to be systematic differences across videos such that we pooled data across videos and participants to examine engagement in terms of the quality of the user’s experience, acceptability, and usefulness of the content. Caregivers rated the audio quality of videos as high to very high (N = 23; 100%) and video quality as high to very high (N = 21; 100%). Participants generally reported the length of videos was just about right (N = 20/21; 95%). All participants reported videos as easy to very easy to understand (N = 21; 100%). Caregivers reported videos as a little bit useful (N = 1/21; 5%), useful (N = 2/21; 9%), and very to extremely useful (N = 18/21; 86%). Caregivers felt that overall, videos were not at all or a little relevant (N = 4/21; 19%), relevant (N = 3/21; 15%), and very and extremely relevant (N = 14/21; 66%). Ninety-five percent of caregivers reported being very satisfied with the videos (N = 20/21) and 95% indicated they would “definitely recommend the intervention to other families” (N = 20/21).

Phone follow-up interviews provided additional descriptions of engagement and perceived utility of the intervention. Five of six caregivers who had watched at least one video in the program reported engaging in at least one behavioral pain management strategy such as distraction, relaxation skills (e.g., deep breathing, progressive relaxation, guided imagery), activity pacing, pleasant activity scheduling, rewarding desired behaviors, active ignoring, encouraging regular activity, modeling desired behaviors, and others. Caregivers reported practicing behavioral pain management skills 11 times out of 20 opportunities in the postvideo follow-up phone interview. Of note, caregivers were not directly told to practice these strategies in between sessions and most children did not experience a pain crisis during the intervention. Caregivers practicing these skills rated the perceived utility of these strategies as “useful” to “very useful” (100%). One caregiver reported their child having a pain crisis over the course of the intervention. Having watched two intervention videos at the time of their child’s crisis, the caregiver reported utilizing guided imagery and activity pacing as pain management strategies and rated these strategies as “very successful” in helping them manage their child’s pain.

Mean pre–post change scores were used to describe observed changes in parent pain catastrophizing as well as adult responses to youth’s pain. Among the three caregivers completing the intervention (N = 3), differences in total parent pain catastrophizing scores were MΔ = −13.00. Differences in specific catastrophizing scale scores were: magnification (MΔ = −4.00), rumination (MΔ = −5.00), and helplessness (MΔ = −4.00). Concerning caregiver responses to youth’s pain, differences in protective parent behavior scores were MΔ = −6.00. Additionally, differences in monitoring/encouraging were MΔ = −3.00 and differences in minimizing behaviors were MΔ = +1.33. For reference purposes, we computed RC criteria scores (Christensen & Mendoza, 1986; Goubert et al., 2006; Van Slyke & Walker, 2006). For parent pain catastrophizing total score, the RC value was 8.24. For the ARCS Protect scale, the RC value was prorated based on only administering nine items and resulted in an RC of 5.67 for our scale. The Minimize and Monitor/Encourage scales had RC values of 5.52 and 6.16, respectively. For the total pain catastrophizing score and the ARCS Protect scale, the mean change scores of the three completers were larger than the RC values, suggesting the pre–post difference was systematic. Although the goal was not to assess the efficacy of the intervention, it is noted here that the direction of change in parent catastrophizing total score and the ARCS Protect scale were consistent with the intervention goals (Langer et al., 2009) and suggest these scales have utility for assessing change in subsequent evaluations of the intervention.

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine several aspects of feasibility for an eHealth intervention for behavioral pain management directed at caregivers of very young children with SCD with parents initially engaged via their sickle cell specialty clinic. To our knowledge, this is the first study to contribute data on an intervention exclusively targeting caregivers and supporting behavioral pain management in very young children with SCD. Findings related to response to recruitment, engagement, acceptability and usefulness of the intervention, and suitability of outcome measures are summarized below. Information about barriers to participation are integrated into the discussion where relevant.

Response to recruitment was generally in line with what was expected based on a prior survey of interest in behavioral pain management education in this target group. Fifty percent of those eligible were enrolled in the intervention, which is generally consistent with those who indicated they were “very likely” to want to participate in such a program (59%; 95% CI: 44%–73%; Smith et al., 2018). Different patterns of engagement with the intervention were observed with three caregivers completing the intervention and three caregivers watching one-to-three videos in the program. This rate of engagement is lower than what was observed in a larger intervention that we chose as a comparison due to similarities in its methods (Day & Sanders, 2018). Although variable engagement in behavioral pain management programs, even those delivered in-home, is common among patients with SCD (Sil et al., 2020), 4 of 10 participants enrolled in the study did not watch any intervention videos suggesting addressing potential barriers to engagement would be beneficial. One facet of the intervention that may have posed a barrier was the structure as a formal research study. The research team that introduced the program, obtained consent, and completed study follow-up procedures did not have a prior relationship with the caregivers. In a prior survey, parents of preschool children with SCD expressed a strong interest in having clinic staff involved in behavioral pain management education (Smith et al., 2018). It is possible that recruitment and engagement in the program would benefit from incorporating familiar clinic staff into the intervention.

Other factors that may have impacted engagement include the pain history of the child, technological barriers, and social stressors. Two of the four caregivers who did not watch videos in the intervention had not yet experienced a pain crisis child, suggesting that having a child who already experienced pain could be a helpful context for the intervention. One caregiver was unable to access pain management videos on her phone and after unsuccessful trouble shooting became disengaged. Finally, caregivers of children with SCD face many social stressors, including health-related stigma, socioeconomic disadvantage, frequent disruptions to daily life, and emotional distress which may impact engagement with healthcare services (Edwards & Edwards, 2010; Madani et al., 2018; Wesley et al., 2016). These stressors, in combination with the demands of parenting a child with a chronic medical condition, could contribute to limited time to participate in an intervention viewed as supplemental to youth’s primary medical care. High caregiver demands were also identified as a reason for not participating in the intervention, supporting that competing responsibilities could prevent engagement with the intervention.

There are a number of potential modifications that may improve these barriers to engagement. First, parents may benefit from the option to incorporate behavioral pain management training into routine sickle cell visits to reduce the impact of technological barriers and ameliorate difficulties scheduling time for the activity due to competing demands. This method of delivery would likely necessitate tailoring the intervention (e.g., selecting certain pain management videos to be watched at specific visits) according to the frequency with which preschool-aged youth routinely receive medical care and caregiver needs. Preschool children may be seen in the clinic anywhere from twice a year to monthly depending on their treatment plan and illness course, which would impact what content and how quickly this information is delivered to caregivers. Second, caregivers may benefit from greater flexibility in intervention delivery (Sil et al., 2020) such as a modular-based approach. For instance, the education program could be tailored to families based on information collected to determine which intervention materials are most likely address specific behavioral pain management needs of the parent. Finally, caregivers may benefit from streamlined approaches to follow-up. For example, use of electronic surveys with open-ended questions may eliminate additional burden required by the intervention as tested (e.g., phone and online follow-up). Ultimately, more data are needed to understand how to engage parents in a manner that addresses potential barriers but still achieves the learning objectives of the program.

Process data from the pilot study support the intervention as highly acceptable to caregivers who engaged in the intervention. Specifically, caregivers perceived the intervention to be of high quality, easy to understand, and nearly all participants were very satisfied with all videos in the program. The majority of caregivers reported intent to recommend the intervention to other caregivers and rated information contained in the educational videos as useful and relevant. Some caregivers, however, reported that the content contained in certain videos was only “a little bit” useful or relevant. It is noteworthy that these findings were contributed by caregivers with a child who had not yet experienced a pain crisis and by a caregiver whose child experienced developmental delays in addition to SCD. As previously noted, having a child who has already experienced a pain crisis might be helpful context for intervention education. Additionally, some of the behavioral pain management strategies presented in the videos may not be feasible to complete with a young child with developmental delay (e.g., guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation), whereas other strategies (e.g., operant strategies) could be more relevant and useful for this particular caregiver. Ultimately, caregivers may benefit from education about pain management as a preventative approach, but additional research is needed to clarify to what extent a history of prior pain crises affects the acceptability of the intervention.

Preliminary findings regarding the measures used to assess pre–post change are encouraging. The PCS-P as a measure of parent catastrophizing trended downward with mean changes demonstrating reductions on all subscales of catastrophizing including rumination, magnification, and helplessness. Because of the very small sample, these data are not good indicators of efficacy or expected effect sizes but provide support that these measures are likely sensitive to change in the context of this intervention. Additionally, caregivers generally reported decreased protective and monitoring behaviors on the ARCS. There is the greatest amount of empirical support linking protective behaviors with negative outcomes for youth (Levy et al., 2010; Logan et al., 2012; Pielech et al., 2018). Our modified version of the ARCS dropped items that seemed to have less appropriate content for preschool children with SCD, which occurred most often for items on the protective behavior scale. As such, the present data are encouraging that the ARCS can be modified and still be sensitive to change for our target population. Additional assessment of the ARCS with preschoolers is needed to understand its reliability and validity in this age range.

Findings must be considered in the context of additional limitations to the present study. First, our findings are preliminary, based on a very small sample size, and may not generalize to the broader population of caregivers with SCD. Caution should be exercised when interpreting all preliminary primary and secondary data from this intervention. Second, this intervention study did not include a control group (e.g., no treatment, wait-list) and future research is needed to determine the relative benefit of the intervention compared to treatment as usual. Third, we were unable to determine the extent to which parents partially completing the intervention benefited as we were unable to collect follow-up data from these participants. Along these lines, we were also unable to reach participants with low engagement (via phone, text, and e-mail) to inquire about barriers to their participation. This information is critical to better understand how families may benefit from the intervention. Authors plan to conduct semistructured exit interviews from all participants in the future to collect caregiver feedback about barriers to the intervention, overall acceptability of the intervention, satisfaction with content, and benefits of the intervention. The COVID-19 pandemic also interrupted the intervention study and caregiver engagement with the intervention may reflect the effects of this unexpected environmental stressor. However, there did not appear to be differences in response to measures based upon whether caregivers finished the intervention prior to or during the pandemic. Another limitation to this study is the lack of a measure of fidelity, or whether parents truly watched each pain management video, due to the platforms researchers selected for the study. In the future, researchers hope to develop a method through which fidelity can be confirmed without compromising confidentiality. Caregivers were also not explicitly directed to practice behavioral pain management strategies in the current intervention. We plan to include this directive in our future implementation of this intervention to help caregivers develop familiarity and competence with behavioral strategies that are specific to pain management (e.g., deep breathing) as well as general positive parenting practices (e.g., modeling positive coping).

Conclusions

In summary, preliminary findings suggest the Preschool Pain Management Program is acceptable and perceived as useful to caregivers of youth with SCD who engage in the program, but additional modifications are needed to improve the rate of engagement. In our current context, we believe greater integration of the intervention into routine hematology care visits and a more flexible and modular-based approach may be beneficial for engagement. These methods will be tested in a future pilot study. Additional research is needed to understand how to best serve caregivers of preschool-aged children with SCD.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.