-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alexandra Main, Carmen Kho, Maritza Miramontes, Deborah J Wiebe, Nedim Çakan, Jennifer K Raymond, Parents’ Empathic Accuracy: Associations With Type 1 Diabetes Management and Familism, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 47, Issue 1, January-February 2022, Pages 59–68, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab073

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To (1) test associations between parents’ empathic accuracy for their adolescents’ positive and negative emotions and adolescents’ physical and mental health (HbA1c, diabetes self-care, and depressive symptoms) in a predominantly Latinx sample of adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their parents, and (2) explore how familism values were associated with parent empathic accuracy and adolescent physical and mental health in this population.

Parents and adolescents engaged in a discussion about a topic of frequent conflict related to the adolescents’ diabetes management. Parents and adolescents subsequently completed a video recall task in which they rated their own and their partner’s emotions once per minute; parents’ empathic accuracy was calculated from an average discrepancy between parent and adolescent ratings of the adolescent’s emotions. Adolescents reported on their depressive symptoms and both parents and adolescents reported on adolescents’ diabetes self-care and their own familism values; HbA1c was obtained from medical records.

Results from structural equation modeling revealed that parents’ empathic accuracy for adolescents’ negative (but not positive) emotions was uniquely associated with adolescents’ HbA1c, self-care, and depressive symptoms. There was limited evidence that familism was related to parent empathic accuracy or adolescent physical and mental health.

Promoting parents’ empathic accuracy for adolescents’ negative emotions in the context of type 1 diabetes management may have important implications for adolescents’ mental and physical health.

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is a rapidly increasing pediatric chronic illness, particularly among Latinx youth (Mayer-Davis et al., 2017). Type 1 diabetes can have serious health consequences (Hamman et al., 2014), but positive health outcomes can be achieved with proper management (Wysocki & Greco, 2006). Parent empathic accuracy—a parent’s correct inferences about their child’s thoughts and feelings (Ickes, 1993)—may improve diabetes management because it allows caregivers to understand their child’s specific needs (Vervoort et al., 2007). A handful of studies have examined parent empathic accuracy, and parent empathy more broadly, in the context of chronic illness management in adolescence (Harper et al., 2012; Penner et al., 2008; Vervoort et al., 2007). However, no studies to our knowledge have examined how parents’ empathic accuracy is associated with physical and mental health in the context of type 1 diabetes management. Identifying links between parent empathic accuracy for adolescent’s emotions related to diabetes management and adolescent health during real-time interactions will help develop and inform family-centered interventions (see McBroom & Enriquez, 2009) to improve family communication in order to promote better physical and mental health.

According to a relational perspective on empathy (Main et al., 2017), empathy is an interpersonal construct that involves attempting to imagine and understand the cognitions and emotions of a social partner. Parent empathic accuracy for their adolescents’ emotions surrounding their diabetes management is likely linked with other constructive aspects of parent-adolescent communication that are predictive of better diabetes management, including greater parental support, reduced conflict, and positive problem-solving (see Dashiff et al., 2008). Although parental empathy has not been examined in the context of managing a demanding illness such as type 1 diabetes, there are reasons to believe it may be helpful. For example, parents often underestimate the negative emotions children experience regarding their illness, which may impede parents’ ability to understand the emotional and instrumental support needs of their children (Vervoort et al., 2007). Though they did not examine parental empathy directly, Mello et al. (2017) found that mothers’ lower awareness of their adolescent’s diabetes-related problems was associated with lower self-care. Parents’ misunderstandings of their children’s feelings surrounding diabetes management might also be associated with negative relationship processes such as conflict (e.g., Campbell et al., 2019), which is linked with higher HbA1c (Rybak et al., 2017). Thus, parents’ ability to accurately empathize with their adolescent’s emotions during conflicts might be particularly important for facilitating positive parent-adolescent communication, which in turn can lead to better diabetes management.

Researchers are increasingly acknowledging the importance of dynamic, interpersonal assessments of empathy to capture real-time responses to social partners’ thoughts and feelings (see Main et al., 2017). Video recall paradigms, in which dyads engage in a videotaped interaction followed by ratings of their own and their partner’s thoughts and feelings during the interaction, allow for an evaluation of real-time concordance (or lack thereof) between an individual’s own perceptions and how their social partner perceived their mental state (Diamond et al., 2012). Studies in the pediatric literature that have measured parent empathic accuracy using video-assisted recall have found that parents tend to be less empathically accurate about their child’s thoughts and feelings about the illness itself than about children’s thoughts and feelings about other topics (Vervoort et al., 2007) and empathic inaccuracies are associated with lower perceptions of shared understanding (McLaren & Pederson, 2014). However, these studies did not examine whether parent empathic accuracy was associated with children’s illness management. Furthermore, studies of parent-adolescent relationships in the context of type 1 diabetes management typically use self-report (for studies that use observational methods, see Gruhn et al., 2016; Jaser & Grey, 2010) or global aspects of parenting (e.g., parent acceptance). Understanding links between parent empathic accuracy and adolescent diabetes management may help develop programs that build on existing family-focused interventions (e.g., Wysocki et al., 2006) to strengthen specific parenting skills in interactions with their children during a pivotal developmental period for parent–child relationships.

Bioecological models of development emphasize the importance of testing micro-level processes (e.g., family dynamics) within sociocultural contexts in which families live (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Most studies of adolescents with type 1 diabetes have focused on predominantly European American families. However, rates of type 1 diabetes are increasing in Latinx youth (Mayer-Davis et al., 2017) and family relationship characteristics differ between Latinx and European American youth with type 1 diabetes (e.g., Main et al., 2014). Accurately appreciating others’ feelings is linked with interpersonal harmony, which is emphasized in Latinx cultural contexts. Indeed, parents’ endorsement of the Latinx cultural value of familism (i.e., an emphasis on the importance of family as a source of support, obligation, and deference; Campos et al., 2016) is protective against negative adolescent outcomes (Santisteban et al., 2012). Parents who more strongly adhere to familism values may be more motivated to understand their child’s thoughts and feelings, and greater familism is linked with other parenting behaviors (e.g., less harsh parenting, greater emotional support) that may affect outcomes uniquely in Latinx families (Krauthamer Ewing et al., 2019). Indeed, prior research has shown that greater interdependence—a cultural construct associated with familism—is linked with greater motivation to understand the feelings of close others (Ma-Kellams & Blascovich, 2012). While these findings suggest familism may be associated with greater empathic accuracy in the family context, an emphasis on family obligation could reduce parents’ focus on their individual child’s feelings as they could detract from the collective functions of the family. In the diabetes literature, Latinx adolescents report greater conflict with parents than European American adolescents (Main et al., 2014; Nicholl et al., 2019) and Latinx mothers and adolescents have less congruence on reports of diabetes-related stressors (Mello et al., 2017). More research is needed with diverse samples examining how family dynamics are linked with mental and physical health in the context of managing type 1 diabetes.

The current study examined parental empathic accuracy during observed family interactions in a predominantly Latinx sample; a population at increasing risk for developing type 1 diabetes (Mayer-Davis et al., 2017) and that is expected to surpass European Americans as the largest ethnic group in the United States by 2060 (Colby & Ortman, 2015). This study is innovative in its use of a video-assisted recall task to examine associations between parents’ empathic accuracy for adolescents’ negative (e.g., feeling angry, sad) and positive emotions (e.g., feeling understood, accepted) during a discussion on a contentious topic related to adolescents’ type 1 diabetes management in a sample of predominantly Latinx families. We used structural equation modeling to test whether parents’ empathic accuracy for adolescents’ positive and negative emotions were independently associated with adolescents’ physical health (HbA1c, diabetes self-care) and mental health (depressive symptoms). We hypothesized that parents’ empathic accuracy for both positive and negative emotions would be associated with lower HbA1c, higher self-care, and fewer depressive symptoms. The study had a secondary, exploratory aim to test associations between parent and adolescent familism values and parent empathic accuracy and adolescent physical and mental health. Given mixed findings in prior diabetes literature on parent–adolescent relationships and possible disparities in diabetes outcomes among Latinx youth (Main et al., 2014; Mello et al., 2017; Mello & Wiebe, 2020), we did not have specific hypotheses about the direction of associations between familism and parent empathic accuracy or physical and mental health.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 84 adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (Mage = 12.74 years, 58% female) and their parents (86% mothers) who participated in a multisite study of family communication about type 1 diabetes during adolescence. Eighty-one percent of the adolescents in the sample identified as Latinx, 14% European American, 1% Black, and 4% Other. The present study is based on the 71 dyads who agreed to participate in the conflict discussion task and thus had video recall data available for analysis.1 Adolescents and parents were recruited at their pediatric endocrinology clinic in a small city in an agricultural region of Central California (N = 38 families) and a large metropolitan area in Southern California (N = 46 families). Both clinics serve a diverse community of predominantly lower-socioeconomic status (SES) families; 73% of the sample received public or no insurance to cover the adolescent’s diabetes care. There were no differences in HbA1c, diabetes self-care, or depressive symptoms across sites. Adolescents were eligible if diagnosed with type 1 diabetes for at least one year, were 10–15 years of age at the time of participation (when diabetes management typically declines; Spaans et al., 2020), could read and speak English or Spanish, and had no condition to prohibit study completion (e.g., severe intellectual disability). Of the 184 qualifying families approached (102 from Central California, 82 from Southern California), 38 were enrolled from Central California and 46 were enrolled from Southern California, while 29 from Central California and 36 from Southern California declined. Reasons for refusal included distance or transportation problems, too busy, and scheduling conflicts. An additional 35 families expressed interest but could not be reached to schedule a research appointment.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site, with parents providing informed consent and adolescents providing assent. Procedures involved an in-person laboratory session that consisted of surveys and an observed conflict discussion followed by the video recall task (described in detail below). Parents and adolescents completed the assessments in the language in which they were most comfortable, with 69% of parents and all but one adolescent completing the assessment in English. Parents were paid $20 for completing the laboratory procedures and surveys and adolescents were given a $20 gift card.

Parents and adolescents independently identified a discussion topic using the Diabetes Family Conflict Scale (Hood et al., 2007), which asks participants to indicate how much they argued in the past month about 20 topics related to diabetes management (e. g, “remembering to check blood sugars”) on a scale of 1 (never) to 3 (almost always). The topic rated most highly by both parents and adolescents was chosen for them to discuss; dyads subsequently discussed this topic for 10 minutes without a researcher present. A researcher provided the following instructions: “A little while ago, each of you read through a list of topics that parents and teens with diabetes often talk about. You each identified the topics that you have talked about during the last month and rated which ones made you feel most upset. You both chose [topic] as a ‘hot’ topic for the last month. For the next 10 minutes, I would like for you to discuss with each other what the topic is and how it makes you feel. Try to focus on the other person’s feelings and point of view during your discussion. We would like for both of you to contribute to the discussion. We will come back in after the time is up.” Participants were given a card with three questions for them to address to remind them of the purpose of the task: (1) What is the topic? (2) How does it make each of you feel? Why? (3) What might be a good solution? The researcher knocked on the door when one minute remained and knocked and re-entered the room after 10 minutes. Families completed the discussion in their preferred language.

Measures

Demographic- and Illness-Related Variables

Parents reported their adolescent’s gender, birthdate, parents’ highest level of education, annual household income, and whether the adolescent was on an insulin pump or a continuous glucose monitor. Illness duration was obtained from the diagnosis date indicated in adolescents’ medical records (see Table 1 for descriptive information about the sample).

| Variable . | Minimum . | Maximum . | Mean . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent empathic accuracy | ||||

| 1. Negative | 1.88 | 6.00 | 5.16 | 0.80 |

| 2. Positive | 0.46 | 6.00 | 4.46 | 1.11 |

| Adolescent physical/mental health | ||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | 2.00 | 19.00 | 13.81 | 6.48 |

| 4. HbA1c | 5.80 | 11.80 | 8.52 | 1.19 |

| 5. Self-care (P) | 2.81 | 5.00 | 4.24 | 0.49 |

| 6. Self-care (A) | 3.27 | 5.00 | 4.27 | 0.43 |

| Familism values | ||||

| 7. Familism (P) | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.93 | 0.65 |

| 8. Familism (A) | 2.80 | 5.00 | 4.10 | 0.59 |

| Demographic and illness variables | ||||

| 9. Adolescent gender (% female) | 53.60 | |||

| 10. Adolescent age (years) | 10 | 15 | 12.74 | 1.74 |

| 11. Primary caregiver educationa | 1.00 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| 12. Median family annual household income | <$5,000 | >$100,000 | $29,000–$49,999 | $15,000–$74,999 |

| 13. Pump status (% yes) | 38.10 | |||

| 14. Continuous glucose monitor (% yes) | 25.00 | |||

| 15. Illness duration (years) | 1.00 | 14.00 | 5.00 | 3.11 |

| Variable . | Minimum . | Maximum . | Mean . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent empathic accuracy | ||||

| 1. Negative | 1.88 | 6.00 | 5.16 | 0.80 |

| 2. Positive | 0.46 | 6.00 | 4.46 | 1.11 |

| Adolescent physical/mental health | ||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | 2.00 | 19.00 | 13.81 | 6.48 |

| 4. HbA1c | 5.80 | 11.80 | 8.52 | 1.19 |

| 5. Self-care (P) | 2.81 | 5.00 | 4.24 | 0.49 |

| 6. Self-care (A) | 3.27 | 5.00 | 4.27 | 0.43 |

| Familism values | ||||

| 7. Familism (P) | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.93 | 0.65 |

| 8. Familism (A) | 2.80 | 5.00 | 4.10 | 0.59 |

| Demographic and illness variables | ||||

| 9. Adolescent gender (% female) | 53.60 | |||

| 10. Adolescent age (years) | 10 | 15 | 12.74 | 1.74 |

| 11. Primary caregiver educationa | 1.00 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| 12. Median family annual household income | <$5,000 | >$100,000 | $29,000–$49,999 | $15,000–$74,999 |

| 13. Pump status (% yes) | 38.10 | |||

| 14. Continuous glucose monitor (% yes) | 25.00 | |||

| 15. Illness duration (years) | 1.00 | 14.00 | 5.00 | 3.11 |

Note. (A) = adolescent report; (P) = parent report; SD = standard deviation.

1 = some high school or less, 2 = high school graduate or equivalent, 3 = some college, 4 = associates/vocational degree, 5 = bachelors degree, 6 = Masters degree, 7 = MD/PhD/JD. SD for primary caretaker education and median family household income = interquartile range.

| Variable . | Minimum . | Maximum . | Mean . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent empathic accuracy | ||||

| 1. Negative | 1.88 | 6.00 | 5.16 | 0.80 |

| 2. Positive | 0.46 | 6.00 | 4.46 | 1.11 |

| Adolescent physical/mental health | ||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | 2.00 | 19.00 | 13.81 | 6.48 |

| 4. HbA1c | 5.80 | 11.80 | 8.52 | 1.19 |

| 5. Self-care (P) | 2.81 | 5.00 | 4.24 | 0.49 |

| 6. Self-care (A) | 3.27 | 5.00 | 4.27 | 0.43 |

| Familism values | ||||

| 7. Familism (P) | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.93 | 0.65 |

| 8. Familism (A) | 2.80 | 5.00 | 4.10 | 0.59 |

| Demographic and illness variables | ||||

| 9. Adolescent gender (% female) | 53.60 | |||

| 10. Adolescent age (years) | 10 | 15 | 12.74 | 1.74 |

| 11. Primary caregiver educationa | 1.00 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| 12. Median family annual household income | <$5,000 | >$100,000 | $29,000–$49,999 | $15,000–$74,999 |

| 13. Pump status (% yes) | 38.10 | |||

| 14. Continuous glucose monitor (% yes) | 25.00 | |||

| 15. Illness duration (years) | 1.00 | 14.00 | 5.00 | 3.11 |

| Variable . | Minimum . | Maximum . | Mean . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent empathic accuracy | ||||

| 1. Negative | 1.88 | 6.00 | 5.16 | 0.80 |

| 2. Positive | 0.46 | 6.00 | 4.46 | 1.11 |

| Adolescent physical/mental health | ||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | 2.00 | 19.00 | 13.81 | 6.48 |

| 4. HbA1c | 5.80 | 11.80 | 8.52 | 1.19 |

| 5. Self-care (P) | 2.81 | 5.00 | 4.24 | 0.49 |

| 6. Self-care (A) | 3.27 | 5.00 | 4.27 | 0.43 |

| Familism values | ||||

| 7. Familism (P) | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.93 | 0.65 |

| 8. Familism (A) | 2.80 | 5.00 | 4.10 | 0.59 |

| Demographic and illness variables | ||||

| 9. Adolescent gender (% female) | 53.60 | |||

| 10. Adolescent age (years) | 10 | 15 | 12.74 | 1.74 |

| 11. Primary caregiver educationa | 1.00 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| 12. Median family annual household income | <$5,000 | >$100,000 | $29,000–$49,999 | $15,000–$74,999 |

| 13. Pump status (% yes) | 38.10 | |||

| 14. Continuous glucose monitor (% yes) | 25.00 | |||

| 15. Illness duration (years) | 1.00 | 14.00 | 5.00 | 3.11 |

Note. (A) = adolescent report; (P) = parent report; SD = standard deviation.

1 = some high school or less, 2 = high school graduate or equivalent, 3 = some college, 4 = associates/vocational degree, 5 = bachelors degree, 6 = Masters degree, 7 = MD/PhD/JD. SD for primary caretaker education and median family household income = interquartile range.

Empathic Accuracy

A video-assisted recall task was used to assess parents’ and adolescents’ empathic accuracy for each other’s emotions during the discussion (Ickes, 1993; Overall et al., 2012). Only parent empathic accuracy is included in the analyses in the present study. Immediately following the conflict discussion, adolescents and parents were brought into separate rooms and watched the video of their conversation. A researcher stopped the video every minute (10 times throughout the recorded conversation) and participants subsequently rated how much they felt and thought the other person felt each of the following: Angry, frustrated, hurt, sad, cared for, understood, accepted, valued, and close on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The first four emotions were collapsed into a negative score and the latter five were collapsed into a positive score for each segment (Diamond et al., 2012; Overall et al., 2012). Discrepancies were derived by calculating the difference between parents’ and adolescents’ ratings of adolescents’ emotions at each segment, taking the absolute value to adjust for the direction of the difference. Scores were collapsed across the ten segments to create an average discrepancy score; scores were reverse coded to create an empathic accuracy score in which higher values reflect higher empathic accuracy (possible range = 0–7; see Diamond et al., 2012 for a similar approach).

Diabetes Self-Care

An adapted version of the Self-Care Inventory (Lewin et al., 2009) was used to measure self-care in the context of diabetes-related tasks (e.g., checking blood glucose). Mothers and adolescents reported self-care over the past month (1 = never did it to 5 = always did this as recommended without fail), adolescent report: α = .73, parent report: α = .84. This measure has been previously validated for use with a Spanish-speaking sample (Main et al., 2014).

HbA1c

Blood glucose was indexed using glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) obtained from clinic records. HbA1c represents the average blood glucose over the prior 2 or 3 months, with higher levels indicating higher blood glucose indicating poorer diabetes control. The HbA1c value closest to the study appointment (Mdiff = 25 days) was used in analyses.

Depressive Symptoms

The 11-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess adolescent depressive symptoms. Adolescents rated each item on a scale of 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all the time). Scores were summed to create an overall depressive symptoms score, with a higher total score indicating more depressive symptoms. This scale has been previously validated for use with Spanish-speaking samples (Soler et al., 2014) and demonstrated good internal consistency in the current study (α = .86).

Familism Values

Parents and adolescents separately completed the familism subscales (16 items) of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., 2010). Parents and adolescents rated on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely) how much they agreed with statements describing familism values (e.g., “Parents should teach their children that the family always comes first”). A familism score was created by averaging across all items. This measure is valid with adolescents from diverse Latinx backgrounds (Mercado et al., 2019), α = .89 and .91 for parents and adolescents in the current study, respectively.

Analysis Plan

Analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 26) and Mplus (version 8.4) statistical software (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017). Correlation analyses were used to examine zero-order associations among demographic and study variables. A structural equation model (SEM) was specified to test the hypothesized paths from parent empathic accuracy for positive and negative emotions to adolescent HbA1c, self-care, and depressive symptoms. The SEM was tested using full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data and the Maximum Likelihood Robust estimator. Continuous variables were screened for normality; all variables were normally distributed. Parent and adolescent reports of adolescents’ self-care were highly correlated (r = .50, p < .001); thus, a latent factor of diabetes self-care was indicated by parent and adolescent reports. The outcomes were only weakly correlated with one another (see Table 2); thus, they were included in a single model to test unique associations with parent empathic accuracy.

Zero-Order Correlations Among Continuous Demographic, Illness, and Study Variables

| Variables . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent EA Negative | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Parent EA Positive | .18 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | −.24* | −.05 | – | ||||||||

| 4. HbA1c | −.30* | .00 | .18 | – | |||||||

| 5. Self-care (P) | .24* | −.03 | −.21 | −.24* | – | ||||||

| 6. Self-care (A) | .22 | −.00 | −.31** | −.11 | .50** | – | |||||

| 7. Familism (P) | −.14 | −.14 | .02 | −.00 | .21 | .19 | – | ||||

| 8. Familism (A) | −.02 | −.08 | .01 | −.01 | .10 | .35** | .25* | – | |||

| 9. Adolescent age (years) | −.05 | .02 | .08 | .11 | −.37** | −.13 | −.10 | −.33** | – | ||

| 10. Education | −.08 | .09 | .01 | −.01 | −.43** | −.25* | −.42** | −.06 | .20 | – | |

| 11. Income | .19 | .02 | −.08 | −.08 | −.15 | −.17 | −.37** | −.09 | .23* | .42** | – |

| 12. Illness duration (years) | .10 | .06 | .07 | −.00 | .02 | .02 | .02 | −.11 | .13 | −.01 | −.11 |

| Variables . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent EA Negative | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Parent EA Positive | .18 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | −.24* | −.05 | – | ||||||||

| 4. HbA1c | −.30* | .00 | .18 | – | |||||||

| 5. Self-care (P) | .24* | −.03 | −.21 | −.24* | – | ||||||

| 6. Self-care (A) | .22 | −.00 | −.31** | −.11 | .50** | – | |||||

| 7. Familism (P) | −.14 | −.14 | .02 | −.00 | .21 | .19 | – | ||||

| 8. Familism (A) | −.02 | −.08 | .01 | −.01 | .10 | .35** | .25* | – | |||

| 9. Adolescent age (years) | −.05 | .02 | .08 | .11 | −.37** | −.13 | −.10 | −.33** | – | ||

| 10. Education | −.08 | .09 | .01 | −.01 | −.43** | −.25* | −.42** | −.06 | .20 | – | |

| 11. Income | .19 | .02 | −.08 | −.08 | −.15 | −.17 | −.37** | −.09 | .23* | .42** | – |

| 12. Illness duration (years) | .10 | .06 | .07 | −.00 | .02 | .02 | .02 | −.11 | .13 | −.01 | −.11 |

Note. (A) = adolescent report; EA = empathic accuracy; (P) = parent report. Adolescent gender coded as 0 = male, 1 = female. Pump status and continuous glucose monitor (CGM) coded as 0 = not on an insulin pump/CGM, 1 = on an insulin pump/CGM.

p < .05,

p <.01.

Zero-Order Correlations Among Continuous Demographic, Illness, and Study Variables

| Variables . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent EA Negative | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Parent EA Positive | .18 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | −.24* | −.05 | – | ||||||||

| 4. HbA1c | −.30* | .00 | .18 | – | |||||||

| 5. Self-care (P) | .24* | −.03 | −.21 | −.24* | – | ||||||

| 6. Self-care (A) | .22 | −.00 | −.31** | −.11 | .50** | – | |||||

| 7. Familism (P) | −.14 | −.14 | .02 | −.00 | .21 | .19 | – | ||||

| 8. Familism (A) | −.02 | −.08 | .01 | −.01 | .10 | .35** | .25* | – | |||

| 9. Adolescent age (years) | −.05 | .02 | .08 | .11 | −.37** | −.13 | −.10 | −.33** | – | ||

| 10. Education | −.08 | .09 | .01 | −.01 | −.43** | −.25* | −.42** | −.06 | .20 | – | |

| 11. Income | .19 | .02 | −.08 | −.08 | −.15 | −.17 | −.37** | −.09 | .23* | .42** | – |

| 12. Illness duration (years) | .10 | .06 | .07 | −.00 | .02 | .02 | .02 | −.11 | .13 | −.01 | −.11 |

| Variables . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent EA Negative | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Parent EA Positive | .18 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms (A) | −.24* | −.05 | – | ||||||||

| 4. HbA1c | −.30* | .00 | .18 | – | |||||||

| 5. Self-care (P) | .24* | −.03 | −.21 | −.24* | – | ||||||

| 6. Self-care (A) | .22 | −.00 | −.31** | −.11 | .50** | – | |||||

| 7. Familism (P) | −.14 | −.14 | .02 | −.00 | .21 | .19 | – | ||||

| 8. Familism (A) | −.02 | −.08 | .01 | −.01 | .10 | .35** | .25* | – | |||

| 9. Adolescent age (years) | −.05 | .02 | .08 | .11 | −.37** | −.13 | −.10 | −.33** | – | ||

| 10. Education | −.08 | .09 | .01 | −.01 | −.43** | −.25* | −.42** | −.06 | .20 | – | |

| 11. Income | .19 | .02 | −.08 | −.08 | −.15 | −.17 | −.37** | −.09 | .23* | .42** | – |

| 12. Illness duration (years) | .10 | .06 | .07 | −.00 | .02 | .02 | .02 | −.11 | .13 | −.01 | −.11 |

Note. (A) = adolescent report; EA = empathic accuracy; (P) = parent report. Adolescent gender coded as 0 = male, 1 = female. Pump status and continuous glucose monitor (CGM) coded as 0 = not on an insulin pump/CGM, 1 = on an insulin pump/CGM.

p < .05,

p <.01.

Based on prior research demonstrating associations between adolescent age and socioeconomic factors and diabetes management (e.g., Mello & Wiebe, 2020; Spaans et al., 2020) and significance of the zero-order correlations (see Table 2), the SEM included adolescent age and family SES as covariates. A composite SES variable was used in the SEM to reduce the number of variables in the model to preserve power and avoid multicollinearity while accounting for multiple aspects of SES (Yu et al., 2014). The income and education measures were moderately correlated (r = .42, p < .01), and showed similar patterns of associations with study variables (see Table 2). Thus, SES was computed by standardizing primary caretaker education and annual household income and calculating the mean. Pump status was also included as a covariate because there was a trend toward adolescents being on a pump having lower HbA1c (M = 8.23, SD = .95) compared with those not on a pump (M = 8.72, SD = 1.30), t(81) = −1.85, p = .069. There were no differences across any of the dependent variables as a function of adolescent gender, continuous glucose monitor status, or illness duration.

Results

Descriptive statistics of continuous demographic, illness, and study variables are presented in Table 1. Zero-order correlations (see Table 2) revealed no significant association between parent empathic accuracy for adolescent negative and positive emotions. Consistent with our first hypothesis, parent empathic accuracy for negative emotions was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, lower (better) HbA1c values, and higher parent-reported diabetes self-care. There were no significant associations between parent empathic accuracy for positive emotions and any of the dependent variables.

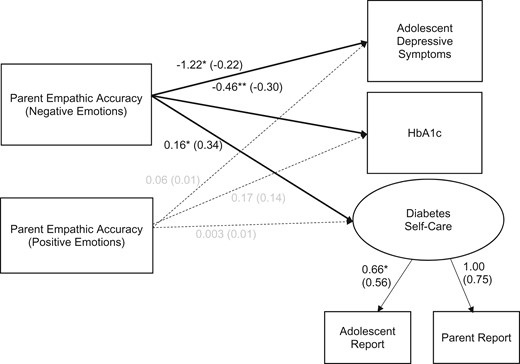

The SEM tested unique associations among parent empathic accuracy for positive and negative emotions and adolescent HbA1c, self-care, and depressive symptoms controlling for SES, adolescent age, and pump status. The model showed a good fit to the data, χ2 (6) = 5.85, p = .44, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.04 (see Figure 1). In line with hypotheses, parents who evidenced higher empathic accuracy for negative emotions during the discussion had adolescents with lower HbA1c, greater self-care, and fewer depressive symptoms. Consistent with the zero-order correlations, empathic accuracy for positive emotions was not significantly associated with any of the outcome variables. Higher family SES was associated with lower self-care (β = −.15, p = .008) but was not significantly associated with HbA1c (β = −.08, p = .68) or depressive symptoms (β = .04, p = .95). Though older adolescents had lower parent-reported self-care in the correlation analyses, this effect was not significant in the SEM.

Structural equation model of associations among parent empathic accuracy and adolescent physical and mental health. Note. Model fit: χ2 (6) = 5.85, p = .44, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.04. Dashed lines represent non-significant paths. Numbers outside parentheses are unstandardized loadings or path coefficients and the numbers inside parentheses are standardized loadings or path coefficients. Although not shown in the figure, the effects of covariates (family socioeconomic status, adolescent age, and pump status) were controlled. *p < .05, **p < .01.

There were no significant correlations between parent or adolescent endorsement of familism and parent empathic accuracy for positive or negative emotions (see Table 2). There was a significant positive association between adolescent familism values and adolescent-reported self-care. There were no other significant associations between parent or adolescent familism and dependent variables.2

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge to link parent empathic accuracy with adolescent physical and mental health in the context of type 1 diabetes management. Using a video recall method, we found that parents’ empathic accuracy for negative emotions (e.g., feeling angry, sad) was uniquely associated with adolescents’ HbA1c, diabetes self-care, and depressive symptoms adjusting for demographic variables; empathic accuracy for positive emotions was not associated with adolescent physical or mental health. There was little evidence of associations between familism values and parent empathic accuracy and adolescent physical and mental health. Findings add to the broader literature on positive parent–adolescent communication and type 1 diabetes management by demonstrating that parent empathic accuracy is uniquely associated with lower HbA1c, greater self-care, and fewer depressive symptoms in an understudied but at-risk population.

When parents were more accurate in their assessment of their adolescent’s negative emotions, adolescents had lower HbA1c, greater self-care, and fewer depressive symptoms controlling for demographic and illness-related variables. This suggests that when parents are more attuned to their adolescent’s negative emotions, adolescents have better physical and mental health in the context of type 1 diabetes management. These findings are consistent with work on physician-patient relationships, in which healthcare providers’ ability to empathize with negative emotions (e.g., anger) is predictive of greater patient disclosure, leading to better treatment (e.g., Halpern, 2007). Type 1 diabetes management involves regulating difficult emotions (Fisher et al., 2018). Parents’ ability to empathize with these emotions might be particularly helpful for supporting their adolescent’s diabetes management. It is compelling that parent empathic accuracy for adolescents’ negative emotions was uniquely associated with HbA1c, self-care, and depressive symptoms. Parents’ ability to empathize with adolescents’ negative emotions appears to confer multiple benefits for behavioral, psychological, and physiological aspects of managing diabetes.

Interestingly, parents’ empathic accuracy for adolescents’ positive emotions (e.g., feeling understood, cared for) was not associated with adolescent physical or mental health. The conversations were about a conflictual topic related to the adolescent’s diabetes, which may have increased parent attunement to negative rather than positive emotions. Indeed, parent empathic accuracy was generally higher for negative compared with positive emotions, and parent empathic accuracy for positive and negative emotions were unrelated to one another. This is consistent with prior research showing that empathy for positive and negative emotions have distinct correlates (Andreychik & Migliaccio, 2015). Moreover, many cultures socialize greater expression of positive than negative emotion (Ekman et al., 1969), such that positive expressions may be less indicative of internal feelings than are expressions of negative emotion (see Zaki et al., 2009). The current study specifically measured empathic accuracy for positive regard, including feeling accepted, understood, and close (see Overall et al., 2012), but did not assess other positive emotions such as joy or humor. Research on parent–adolescent interactions has shown greater synchrony for joy, enthusiasm, and humor than positive regard behaviors, such as validation (Main et al., 2016). Future research could assess a wider array of both positive and negative emotions and examine distinct emotions (e.g., sadness vs. anger) to determine whether associations between empathic accuracy and physical or mental health vary across different emotions.

Given the unique demographics of our sample and the central role of culture in empathy in interpersonal contexts (Main & Kho, 2020), we also explored associations between familism values and parent empathic accuracy and adolescent physical and mental health. There were no significant associations between parent or adolescent familism and parent empathic accuracy. Familism is a broad construct that encompasses multiple aspects of family relationships, including support and the desire for close relationships, obligation to help family members, and deference to family when making decisions and defining the self (see Campos et al., 2016; Knight et al., 2010). Familism may promote parent empathic accuracy in situations in which the parent is motivated to take the child’s perspective to facilitate a bond. However, familism may be associated with lower empathic accuracy in contexts where the child’s distress detracts from the larger goal of maintaining family harmony. Indeed, familism is associated with higher levels of parent demandingness and greater distress in caregiving contexts in Latinx families (Knight et al., 2002), but has also been linked with positive parenting practices (Santisteban et al., 2012). Interestingly, adolescents who reported higher familism reported greater self-care. Adherence to familism values may have motivated adolescents to engage in greater efforts to manage their diabetes to avoid being a burden on the family (Knight et al., 2002). Though underpowered to do so in the current study, future research should tease apart distinct components of familism (e.g., valuing support from family vs. family obligation) when examining links with parenting practices and children’s health.

The current study has several innovative aspects and strengths, including the use of time-intensive methods that capture multiple aspects of family dynamics (observed interactions between parents and adolescents, multiple reporters) in a sample that is challenging to recruit and underrepresented in the literature (i.e., predominantly low SES, Latinx), but at increasing risk of developing type 1 diabetes (Mayer-Davis et al., 2017). However, there are some limitations that warrant mentioning. First, the use of cross-sectional data precluded drawing conclusions about causal associations between parent empathic accuracy and adolescent physical and mental health. It is possible that parents whose adolescents were not managing their diabetes well felt more frustrated, contributing to less emotional attunement and greater invalidation of the adolescent’s feelings. Indeed, adolescents in dyads that declined to participate in the discussion task had lower diabetes self-management than those who participated, perhaps suggesting that adolescents who are managing their illness better may be more willing to openly discuss diabetes-related challenges. Studies testing associations between empathic accuracy and mental health over time, as well as investigating mediating mechanisms that might explain associations between parent empathic accuracy and adolescent health (e.g., disclosure, conflict) using longitudinal data are needed. Second, though the sample size was comparable to other studies examining empathic accuracy in the context of chronic illness management (e.g., Vervoort et al., 2007) and to those using observed interactions between parents and children managing diabetes (e.g., Gruhn et al., 2016; Jaser & Grey, 2010), findings should be with larger samples that allow for greater exploration of familism values and other cultural factors. Third, though the overrepresentation of the Latinx population in the sample is a strength given the lack of focus on this at-risk population in the literature, findings may not fully generalize to other populations.

The current study demonstrates that parents’ ability to accurately infer their adolescent’s negative emotions plays a key role in their adolescents’ mental and physical health (HbA1c, diabetes self-care, and depressive symptoms) in the context of managing type 1 diabetes. This study is novel in its use of a video recall task that allowed us to determine whether parents’ dynamic attunement to their adolescent’s feelings was associated with global features of adolescents’ mental and physical health. Findings from this study can inform interventions with families managing type 1 diabetes and other chronic illnesses. Specifically, healthcare providers and individuals working with families in community settings (e.g., non-profit groups that work on interventions targeted to improve the lives of families) may encourage parents to be attuned to negative feelings their adolescent is experiencing related to their diabetes. Interventions targeting parents’ empathic accuracy for their adolescent’s negative emotions during conflict interactions may be especially helpful for improving diabetes outcomes given the robust support in the literature for links between family conflict and diabetes management (e.g., Majidi et al., 2021; Rybak et al., 2017) and the established efficacy of interventions targeting reducing conflict (McBroom & Enriquez, 2009). Additionally, existing interventions that focus on responsive parenting and positive communication more broadly to improve diabetes management such as Behavioral Family Systems Therapy (Graves et al., 2015; Wysocki et al., 2006) and Positive Parenting Program (Triple P; Doherty et al., 2013) can be strengthened by incorporating explicit teaching of parents to read their child’s emotional cues and attune to their negative feelings. The development of interventions that emphasize strengths-based approaches (e.g., Hilliard et al., 2019) to promote positive diabetes management in diverse populations are needed during this important developmental period.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the University of California, Merced Academic Senate.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Footnotes

There were no differences in demographic or study variables between dyads that participated in the video recall task vs. those that did not, with the exception of parents in dyads who participated in the video recall task reporting higher adolescent diabetes self-care (M = 4.19, SD = .06) compared with those who did not participate in this task (M = 4.48, SD = .11), t(82) = −2.14, p = .036.

Reported results are based on the full sample. Analyses were also conducted for only the Latinx sample. Findings were unchanged with the exception of a nonsignificant path from parent negative empathic accuracy to adolescent depressive symptoms. The significant association of parent negative empathic accuracy with adolescent depressive symptoms that was present in the full sample (ß = −0.15, p = 0.03) did not reach significance in the Latinx only sample (ß = −0.12, p = 0.15).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ashley Mancini at Valley Children’s Hospital, Sarah Gamez Aguilar and Alejandra Torres-Sanchez at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, who assisted with data collection, and the patients and families that participated in the study.