-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Barbara A Morrongiello, Alexandra R Marquis, Amanda Cox, A RCT Testing If a Storybook Can Teach Children About Home Safety, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 46, Issue 7, August 2021, Pages 866–877, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab002

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for children under 19 years of age. For preschoolers, many injuries occur in the home. Addressing this issue, this study assessed if a storybook about home safety could be effective to increase preschoolers’ safety knowledge and reduce their injury-risk behaviors.

Applying a randomized controlled trial design, normally developing English speaking preschool children (3.5–5.5 years) in Southwestern Ontario Canada were randomly assigned to the control condition (a storybook about healthy eating, N = 30) or the intervention condition (a storybook about home hazards, N = 29). They read the assigned storybook with their mother for 4 weeks; time spent reading was tracked, and fidelity checks based on home visits were implemented.

Comparing postintervention knowledge, understanding score, and risk behaviors across groups revealed that children who received the intervention were able to identify more hazards, provide more comprehensive safety explanations, and demonstrate fewer risky behaviors compared with children in the control group (ηp2 = 0.13, 0.19, and 0.51, respectively), who showed no significant changes over time in safety knowledge, understanding, or risk behaviors. Compliance with reading the safety book and fidelity in how they did so were very good.

A storybook can be an effective resource for educating young children about home safety and reducing their hazard-directed risk behaviors.

Introduction

Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for children 1–19 years of age (World Health Organization [WHO], 2008). For young children (<6 years), their greatest risk of injury occurs in the home (Beautrais et al., 1981; Shanon et al., 1992). This risk arises for a variety of reasons, including that young children’s understanding of danger is limited, their curiosity and emerging physical skills can lead to impulsive interactions with hazards, and they often attempt to model parent behaviors even though these are beyond their capabilities and attempting these can lead to injury (e.g., Morrongiello & Dawber, 1998; Schwebel et al., 2017). In addition, parents have been shown to overestimate their young children’s understanding of safety rules and ability to follow these, which are both risk factors associated with childhood injuries (Morrongiello et al., 2001, 2014a). Interventions to improve safety for young children often focus on improving the practices of caregivers (see Gielen & Sleet, 2003; Morrongiello, 2018 for reviews). However, safety interventions that target the child as an agent of change also are needed, particularly because parents normatively reduce supervision as children age, allowing children more independence in making behavioral decisions that can impact their safety (e.g., Morrongiello et al., 2011; Pollack-Nelson & Drago, 2002). Addressing the need for child-focused safety interventions, this study examined whether a storybook can effectively educate preschoolers about home hazards and reduce their injury-risk behaviors.

Research has found that preschool children’s health and safety knowledge can improve when exposed to intervention programs. Educational programs that have successfully increased children’s knowledge have targeted a variety of issues, including: healthy eating, sun safety, fire safety, bicycle safety, safety practices near dogs, and firearm safety (Ganz et al., 2002; Himle et al., 2004; Jiménez-Aguilar et al., 2019; Kenny & Wurtele, 2016; Lakestani & Donaldson, 2015; Loescher et al., 1995; McConnell et al., 1998; Morrongiello et al., 2016; Sinelnikov et al., 2005; Tripp et al., 2000; Wurtele & Owens, 1997; Wurtele et al., 1992). Many of these successful interventions, however, are narrowly focused to prevent one type of injury (e.g., sunburn, dog bite, gun wound), which leaves many gaps in children’s general safety knowledge. Moreover, the primary outcome measure is often children’s knowledge, leaving open the question of whether increases in knowledge translate into improvements in children’s safety practices; this is a significant concern because safety interventions sometimes improve children’s knowledge with no corresponding change in safety behaviors (e.g., Schwebel et al., 2012). In addition, programs that require multiple sessions in schools and/or involve the coordination of many specialized groups for delivery (e.g., researchers, teachers, police, or firefighters) can be challenging to implement broadly (e.g., Morrongiello et al., 2016). The intervention storybook in this study addressed these various gaps in the literature by covering a range of safety topics that affect young children in the home (falls, poison, cuts, and burns). In addition, the content was designed so that it could be delivered with little training and by parents in the home on a flexible schedule that suited them.

Previous research demonstrates that books can be an effective resource for educating young children about health and safety information. For example, Holzheimer et al. (1998) developed a training program to educate young children about asthma. Information was delivered in either a video or book format and findings revealed the book was a more effective resource for increasing children’s knowledge. The researchers attribute the superiority of this resource to the self-paced nature of books; parents can reinforce messages and review information at a pace that suits their child. In addition, books provide parents with the opportunity to assess the areas in which their child lacks understanding and enables them to direct their child’s attention to relevant information that address the child’s gaps in knowledge (Holzheimer et al., 1998). In terms of the design of storybooks, research on young children’s reading of books provides insights into the differential impact of illustrations and text (see Mol & Bus, 2011, for review). Illustrations have been shown to be particularly important for young children because they attract more attention to material than just text (Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2005; Justice et al., 2005, 2008). In terms of the type of illustration preferred by young children, brightly colored and realistic illustrations are favored over black/white cartoon depictions (Brookshire et al., 2002; Fang, 1996).

Drawing on these findings, in this study the storybook emphasized illustrations more so than text to communicate safety messages, the pages were brightly colored, and pictures were highly realistic (i.e., photos of actual children doing different actions). Parents were encouraged to read the story several times a week to their child; repeated exposure to information fosters children’s learning (Horst et al., 2011; Schwab & Lew-Williams, 2016). Research in education has found that providing opportunities for inductive reasoning promotes children’s depth of understanding and generalization to novel but similar situations (Gopnik et al., 2004; Hamers et al., 1998; Klauer & Phye, 2008). Hence, this approach was applied herein by advising parents to identify the specific risk behavior shown and then discuss what the injury consequence could be of doing the behavior and the mechanism of injury, thereby creating a link from specific hazard instances to a general type of injury.

The study objectives were to determine if a storybook about home safety could be effective to increase preschoolers’ safety knowledge and to reduce their injury-risk behaviors. We hypothesized that children in the intervention group who were exposed to safety information would show increased knowledge of home-safety hazards, improved understanding of the injuries that could occur from interacting with these hazards, and decreased risk behaviors (i.e., fewer touches of hazards) at posttest compared with pretest; children in the control group were expected to show no significant changes between pre- and posttest. We also hypothesized that degree of exposure (number of minutes parent read the book) would be positively associated with improvements in knowledge scores in the intervention group.

Materials and Methods

Study Design Overview

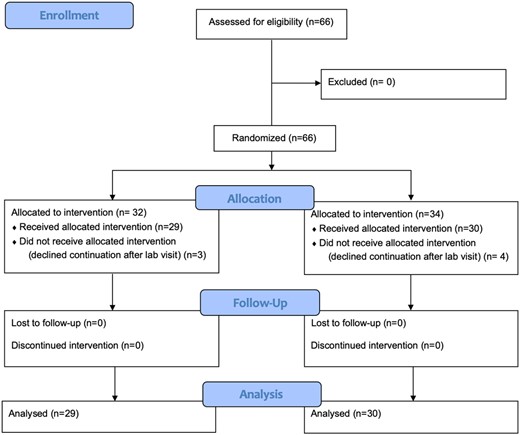

A parallel group trial design was applied. There were two groups, one Intervention and one Control group, and the same pre- and postmeasures were taken in both groups. Figure 1 gives the Consort diagram showing movement and frequencies of participants in both groups throughout this trial.

CONSORT flow diagram of participant progress through randomization.

Recruitment and Randomization

Children were recruited throughout the local community (e.g., general information letters distributed at swim classes, posters hung at locations where child-centered activities occurred) by research assistants. To volunteer to participate, a parent phoned the number provided to register their child in the study. A stratified block randomization procedure (cf. Kernan et al., 1999) was used, with block size fixed at two, to achieve as close as possible an equal number of boys and girls within each group and comparability across groups with respect to children’s age [see Figure 1; Schulz et al. (2010), for the CONSORT statement Group]. In assigning children to groups, a computer-generated random numbers table was used by a research assistant and a concealed method of randomization was applied, with the next assignment only made known to the research assistant at the time of allocation in order to eliminate any potential biases in treatment effects (Schulz et al., 1995).

Participants

A power analysis was conducted using G*Power (Erdfelder et al., 1996). Based on a previous safety intervention study that used the same outcome measures with this age group (Schell et al., 2015), we expected effect sizes would be large (d = 0.84–0.90). For a large effect size with power of 0.80 and alpha of .05, a sample of 26 participants per group was needed. The final sample included 29 participants in the intervention and 30 participants in the control group. Children were 3.50–5.50 years old, with an average age of 4.05 years (SD = 0.83 years). The final sample was comprised of predominantly middle-upper income families (80% earned above $60,000), with 90% of mothers having some/completed college/university, and nearly all of the participants being Caucasian (95%) and in two-parent homes (93%). Complete demographics are presented in Table I.

Summary Demographics for the Intervention (n = 29) and Control (n = 30) Groups, and the Overall Sample (N = 59)

| Attribute . | Intervention . | Control . | Overall samplea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (years) | 3.86 | 4.23 | 4.05 |

| % Male | 55.2 | 53.3 | 54.2 |

| % Female | 44.8 | 46.7 | 45.8 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| % Caucasian | 93.1 | 96.7 | 95.0 |

| % Other | 6.9 | 3.3 | 5.0 |

| Annual family income | |||

| % $60,000 or less | 24.1 | 16.7 | 20.4 |

| % $60,000–$79,999 | 20.7 | 13.3 | 17.0 |

| % $80,000 or higher | 55.2 | 70.0 | 62.6 |

| Mother’s level of education | |||

| % High school | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.2 |

| % University/College | 44.8 | 63.3 | 54.0 |

| % Graduate/Postgraduate | 44.8 | 26.7 | 35.8 |

| Attribute . | Intervention . | Control . | Overall samplea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (years) | 3.86 | 4.23 | 4.05 |

| % Male | 55.2 | 53.3 | 54.2 |

| % Female | 44.8 | 46.7 | 45.8 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| % Caucasian | 93.1 | 96.7 | 95.0 |

| % Other | 6.9 | 3.3 | 5.0 |

| Annual family income | |||

| % $60,000 or less | 24.1 | 16.7 | 20.4 |

| % $60,000–$79,999 | 20.7 | 13.3 | 17.0 |

| % $80,000 or higher | 55.2 | 70.0 | 62.6 |

| Mother’s level of education | |||

| % High school | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.2 |

| % University/College | 44.8 | 63.3 | 54.0 |

| % Graduate/Postgraduate | 44.8 | 26.7 | 35.8 |

One-way analysis of variances (continuous variables) and chi square tests of association (categorical variables) were conducted comparing the intervention and control groups for each variable and results revealed no significant group differences for any demographic factor.

Summary Demographics for the Intervention (n = 29) and Control (n = 30) Groups, and the Overall Sample (N = 59)

| Attribute . | Intervention . | Control . | Overall samplea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (years) | 3.86 | 4.23 | 4.05 |

| % Male | 55.2 | 53.3 | 54.2 |

| % Female | 44.8 | 46.7 | 45.8 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| % Caucasian | 93.1 | 96.7 | 95.0 |

| % Other | 6.9 | 3.3 | 5.0 |

| Annual family income | |||

| % $60,000 or less | 24.1 | 16.7 | 20.4 |

| % $60,000–$79,999 | 20.7 | 13.3 | 17.0 |

| % $80,000 or higher | 55.2 | 70.0 | 62.6 |

| Mother’s level of education | |||

| % High school | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.2 |

| % University/College | 44.8 | 63.3 | 54.0 |

| % Graduate/Postgraduate | 44.8 | 26.7 | 35.8 |

| Attribute . | Intervention . | Control . | Overall samplea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (years) | 3.86 | 4.23 | 4.05 |

| % Male | 55.2 | 53.3 | 54.2 |

| % Female | 44.8 | 46.7 | 45.8 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| % Caucasian | 93.1 | 96.7 | 95.0 |

| % Other | 6.9 | 3.3 | 5.0 |

| Annual family income | |||

| % $60,000 or less | 24.1 | 16.7 | 20.4 |

| % $60,000–$79,999 | 20.7 | 13.3 | 17.0 |

| % $80,000 or higher | 55.2 | 70.0 | 62.6 |

| Mother’s level of education | |||

| % High school | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.2 |

| % University/College | 44.8 | 63.3 | 54.0 |

| % Graduate/Postgraduate | 44.8 | 26.7 | 35.8 |

One-way analysis of variances (continuous variables) and chi square tests of association (categorical variables) were conducted comparing the intervention and control groups for each variable and results revealed no significant group differences for any demographic factor.

The drop-out rate for the study was relatively low at 10% (7/66) and included an additional three children in the Intervention group and four in the Control group who only completed the first lab visit (see Figure 1).

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the university and parents gave written consent.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria included: (a) English speaking family; (b) children were normally developing, based on parent report (i.e., no past or current issues in attention, cognitive, behavioral, or social-emotional functioning); and (c) children were between 3.5 and 5.5 years of age. Exclusion criteria included if any immediate family member had been hospitalized due to injury (N = 0 excluded). These criteria were confirmed at first contact with the volunteering parent by a research assistant.

Materials

Careful Puppy

The researchers developed the book Careful Puppy Saves the Day as the intervention condition, with the aim of educating children about different hazards found in and around the home and the injuries that could occur; the first author was primarily responsible for developing the content and layout of all the books. Throughout the story, a picture of “Careful Puppy” appeared and children were encouraged to help him find children who are doing unsafe things in each room of the home (e.g., bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, hallway, stairway) so he could then make them more safe by telling them to stop. Children were given a “Safety Detective” button to wear as they read the book with their parent. The unsafe pictures depicted behaviors leading to types of injury common to preschool children including burns, cuts, falls, and poisonings (see listing in Table II). The book contained an index card providing parents with instructions on what messages to emphasize about unsafe behaviors while reading the book with their child. The parent was instructed to include three points in discussing unsafe behaviors: (a) describe the activity in the picture and clearly state that it is unsafe (e.g., “Touching knives is not safe.”); (b) elaborate on why it is unsafe (e.g., “Knives are very sharp.”); and (c) state what could happen and/or the type of injury that could result (e.g., “Knives can cut your skin open and that hurts a lot!”).

Unsafe Behaviors Depicted in the Intervention Storybook as a Function of Type of Injury Risk (F = Fall, B = Burn, C = Cut, and P = Poison)

| Activity Featured in Careful Puppy Book . |

|---|

| 1. Walking down cluttered stairs (F) |

| 2. Playing with toys on the staircase (F) |

| 3. Poking at an electrical socket (B) |

| 4. Running through a cluttered hallway (F) |

| 5. Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| 6. Jumping on the couch (F) |

| 7. Holding a fire poker (C) |

| 8. Climbing on a kiddie table (F) |

| 9. Leaning in to look into the wood stove (B) |

| 10. Reaching to open the wood stove door (B) |

| 11. Trying to open a pill bottle (P) |

| 12. Going close to a lit candle (B) |

| 13. Holding a sharp knife (C) |

| 14. Reaching to touch a pot on the stove (B) |

| 14. Reaching to take something out of the open oven (B) |

| 15. Going close to a BBQ (B) |

| 16. Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| 17. Climbing a bunk bed ladder not fully holding on (F) |

| 17. Climbing up dresser drawers (F) |

| 18. Climbing a bookcase (F) |

| 19. Touching a coffee mug that might have hot liquid (B) |

| 19. Playing with a spray bottle of glass cleaner (P) |

| 20. Climbing on the kitchen table (F) |

| 21. Picking up sharp scissors (C) |

| 21. Reaching to touch a hot kettle on the stove (B) |

| 22. Holding spray perfume (P) |

| 22. Holding makeup (P) |

| Activity Featured in Careful Puppy Book . |

|---|

| 1. Walking down cluttered stairs (F) |

| 2. Playing with toys on the staircase (F) |

| 3. Poking at an electrical socket (B) |

| 4. Running through a cluttered hallway (F) |

| 5. Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| 6. Jumping on the couch (F) |

| 7. Holding a fire poker (C) |

| 8. Climbing on a kiddie table (F) |

| 9. Leaning in to look into the wood stove (B) |

| 10. Reaching to open the wood stove door (B) |

| 11. Trying to open a pill bottle (P) |

| 12. Going close to a lit candle (B) |

| 13. Holding a sharp knife (C) |

| 14. Reaching to touch a pot on the stove (B) |

| 14. Reaching to take something out of the open oven (B) |

| 15. Going close to a BBQ (B) |

| 16. Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| 17. Climbing a bunk bed ladder not fully holding on (F) |

| 17. Climbing up dresser drawers (F) |

| 18. Climbing a bookcase (F) |

| 19. Touching a coffee mug that might have hot liquid (B) |

| 19. Playing with a spray bottle of glass cleaner (P) |

| 20. Climbing on the kitchen table (F) |

| 21. Picking up sharp scissors (C) |

| 21. Reaching to touch a hot kettle on the stove (B) |

| 22. Holding spray perfume (P) |

| 22. Holding makeup (P) |

Unsafe Behaviors Depicted in the Intervention Storybook as a Function of Type of Injury Risk (F = Fall, B = Burn, C = Cut, and P = Poison)

| Activity Featured in Careful Puppy Book . |

|---|

| 1. Walking down cluttered stairs (F) |

| 2. Playing with toys on the staircase (F) |

| 3. Poking at an electrical socket (B) |

| 4. Running through a cluttered hallway (F) |

| 5. Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| 6. Jumping on the couch (F) |

| 7. Holding a fire poker (C) |

| 8. Climbing on a kiddie table (F) |

| 9. Leaning in to look into the wood stove (B) |

| 10. Reaching to open the wood stove door (B) |

| 11. Trying to open a pill bottle (P) |

| 12. Going close to a lit candle (B) |

| 13. Holding a sharp knife (C) |

| 14. Reaching to touch a pot on the stove (B) |

| 14. Reaching to take something out of the open oven (B) |

| 15. Going close to a BBQ (B) |

| 16. Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| 17. Climbing a bunk bed ladder not fully holding on (F) |

| 17. Climbing up dresser drawers (F) |

| 18. Climbing a bookcase (F) |

| 19. Touching a coffee mug that might have hot liquid (B) |

| 19. Playing with a spray bottle of glass cleaner (P) |

| 20. Climbing on the kitchen table (F) |

| 21. Picking up sharp scissors (C) |

| 21. Reaching to touch a hot kettle on the stove (B) |

| 22. Holding spray perfume (P) |

| 22. Holding makeup (P) |

| Activity Featured in Careful Puppy Book . |

|---|

| 1. Walking down cluttered stairs (F) |

| 2. Playing with toys on the staircase (F) |

| 3. Poking at an electrical socket (B) |

| 4. Running through a cluttered hallway (F) |

| 5. Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| 6. Jumping on the couch (F) |

| 7. Holding a fire poker (C) |

| 8. Climbing on a kiddie table (F) |

| 9. Leaning in to look into the wood stove (B) |

| 10. Reaching to open the wood stove door (B) |

| 11. Trying to open a pill bottle (P) |

| 12. Going close to a lit candle (B) |

| 13. Holding a sharp knife (C) |

| 14. Reaching to touch a pot on the stove (B) |

| 14. Reaching to take something out of the open oven (B) |

| 15. Going close to a BBQ (B) |

| 16. Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| 17. Climbing a bunk bed ladder not fully holding on (F) |

| 17. Climbing up dresser drawers (F) |

| 18. Climbing a bookcase (F) |

| 19. Touching a coffee mug that might have hot liquid (B) |

| 19. Playing with a spray bottle of glass cleaner (P) |

| 20. Climbing on the kitchen table (F) |

| 21. Picking up sharp scissors (C) |

| 21. Reaching to touch a hot kettle on the stove (B) |

| 22. Holding spray perfume (P) |

| 22. Holding makeup (P) |

Healthy Apple

Researchers developed the Healthy Apple Saves the Day storybook to act as a control condition, with the aim of educating children on healthy eating practices. This book contained pictures of children engaging in healthy and unhealthy eating practices. Throughout the story a picture of “Healthy Apple” appeared and children were encouraged to help the apple find children who are doing unhealthy things so he could then make them healthier by telling them to stop. Children were given a “Health Detective” button to wear as they read the book and helped healthy apple by finding children doing unhealthy things. An index card attached to the book encouraged parents to emphasize health messages during reading sessions with their child, which included messages about three types of issues: food hygiene, snacks, or mealtime manners. These messages included: (a) describing the behavior featured in the picture that is the issue and clearly state that it is not good (e.g., “Eating a lot of candy is not good for you.”); (b) elaborate on why this issue is a concern (e.g., “Eating too much candy can make you feel sick.”); and (c) state what could happen (e.g., “You can get a bad stomach ache, which hurts a lot!”).

Both storybooks featured common elements. Both books were brightly colored and the characters careful puppy and healthy apple were selected based on pilot testing with young children. Each page featured laminated colored pictures of child actors/actresses approximately the same age range as the participants. On each page, there were colored images of children engaging in healthy/unhealthy and safe/unsafe behaviors. A removable green sticker (“green means go so you can keep doing it”) or a removable red sticker (“red means stop so you should stop doing it”) was to be placed on each picture as the child and parent read the book. These stickers were then removed and used for the next page, and so forth, until the end of the book was reached; this allowed the child to apply stickers during every reading of the book. Both books were the same layout and length.

Photo Sorting Task

To generate an index of hazard identification, children were required to sort 36 pictures (randomized order) into boxes labeled Okay To Do (N = 9 nonrisk photos; e.g., child sitting and reading) and Not Okay To Do (N = 27 hazard risk photos); the mother was not present during the photo sort activity. This task has been used successfully in previous research with kindergarten-age children (Morrongiello et al., 2016; Morrongiello et al., 2014b). The list of 27 hazards depicted in the photos can be found in Table III. The child was informed that they were not required to have an equal number of pictures in each box. A research assistant read the label on the back of the photo that identified what was featured in the photo (e.g., “This child is playing with toys on the steps.”). She then handed it to the child for him/her to place it in one of the two boxes; testers were naïve as to child’s group assignment when the child completed this task.

Hazards in the Photo Sorting Task (N = 27) That Were Depicted in Visit One (Preintervention) and Two (Postintervention)

| Activity in which the child is engaged . |

|---|

| Picking up a spray bottle of cleaner (P) |

| Picking up a container of makeup (P) |

| Picking up a container of spray perfume (P) |

| Holding a medicine bottle that has pills inside (P) |

| Reaching for the handle of a pot on the stove (B) |

| Reaching to open the door of a woodstove (B) |

| Standing near a lit candle (B) |

| Going near the open oven (B) |

| Going near a kettle (light on) (B) |

| Reaching to touch a mug of hot liquid (B) |

| Leaning in to look in the glass section of the woodstove door (B) |

| Poking with a pen at an electrical socket (B) |

| Going near the open barbecue (B) |

| Playing with toys on the top of the stairs (F) |

| Jumping on the couch (F) |

| Climbing onto the kitchen table (F) |

| Climbing up a dresser (drawers open) (F) |

| Climbing onto a kiddie table (F) |

| Walking down the stairs carrying toys with toys scattered on steps (F) |

| Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| Climbing up a ladder on a bunk bed (not holding on well) (F) |

| Running down a hallway (toys scattered on floor) (F) |

| Climbing up on a bookcase (F) |

| Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| Reaching to pick up a steak knife (C) |

| Reaching to pick up adult scissors (sharp/pointy) (C) |

| Holding a sharp fireplace poker (C) |

| Activity in which the child is engaged . |

|---|

| Picking up a spray bottle of cleaner (P) |

| Picking up a container of makeup (P) |

| Picking up a container of spray perfume (P) |

| Holding a medicine bottle that has pills inside (P) |

| Reaching for the handle of a pot on the stove (B) |

| Reaching to open the door of a woodstove (B) |

| Standing near a lit candle (B) |

| Going near the open oven (B) |

| Going near a kettle (light on) (B) |

| Reaching to touch a mug of hot liquid (B) |

| Leaning in to look in the glass section of the woodstove door (B) |

| Poking with a pen at an electrical socket (B) |

| Going near the open barbecue (B) |

| Playing with toys on the top of the stairs (F) |

| Jumping on the couch (F) |

| Climbing onto the kitchen table (F) |

| Climbing up a dresser (drawers open) (F) |

| Climbing onto a kiddie table (F) |

| Walking down the stairs carrying toys with toys scattered on steps (F) |

| Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| Climbing up a ladder on a bunk bed (not holding on well) (F) |

| Running down a hallway (toys scattered on floor) (F) |

| Climbing up on a bookcase (F) |

| Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| Reaching to pick up a steak knife (C) |

| Reaching to pick up adult scissors (sharp/pointy) (C) |

| Holding a sharp fireplace poker (C) |

Note. Hazards showed risks for poison (P), burns (B), falls (F), and cuts (C).There were variations in photos for each activity to avoid identical photos being presented across sessions.

Hazards in the Photo Sorting Task (N = 27) That Were Depicted in Visit One (Preintervention) and Two (Postintervention)

| Activity in which the child is engaged . |

|---|

| Picking up a spray bottle of cleaner (P) |

| Picking up a container of makeup (P) |

| Picking up a container of spray perfume (P) |

| Holding a medicine bottle that has pills inside (P) |

| Reaching for the handle of a pot on the stove (B) |

| Reaching to open the door of a woodstove (B) |

| Standing near a lit candle (B) |

| Going near the open oven (B) |

| Going near a kettle (light on) (B) |

| Reaching to touch a mug of hot liquid (B) |

| Leaning in to look in the glass section of the woodstove door (B) |

| Poking with a pen at an electrical socket (B) |

| Going near the open barbecue (B) |

| Playing with toys on the top of the stairs (F) |

| Jumping on the couch (F) |

| Climbing onto the kitchen table (F) |

| Climbing up a dresser (drawers open) (F) |

| Climbing onto a kiddie table (F) |

| Walking down the stairs carrying toys with toys scattered on steps (F) |

| Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| Climbing up a ladder on a bunk bed (not holding on well) (F) |

| Running down a hallway (toys scattered on floor) (F) |

| Climbing up on a bookcase (F) |

| Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| Reaching to pick up a steak knife (C) |

| Reaching to pick up adult scissors (sharp/pointy) (C) |

| Holding a sharp fireplace poker (C) |

| Activity in which the child is engaged . |

|---|

| Picking up a spray bottle of cleaner (P) |

| Picking up a container of makeup (P) |

| Picking up a container of spray perfume (P) |

| Holding a medicine bottle that has pills inside (P) |

| Reaching for the handle of a pot on the stove (B) |

| Reaching to open the door of a woodstove (B) |

| Standing near a lit candle (B) |

| Going near the open oven (B) |

| Going near a kettle (light on) (B) |

| Reaching to touch a mug of hot liquid (B) |

| Leaning in to look in the glass section of the woodstove door (B) |

| Poking with a pen at an electrical socket (B) |

| Going near the open barbecue (B) |

| Playing with toys on the top of the stairs (F) |

| Jumping on the couch (F) |

| Climbing onto the kitchen table (F) |

| Climbing up a dresser (drawers open) (F) |

| Climbing onto a kiddie table (F) |

| Walking down the stairs carrying toys with toys scattered on steps (F) |

| Sitting on the edge of a kiddie table (F) |

| Climbing up a ladder on a bunk bed (not holding on well) (F) |

| Running down a hallway (toys scattered on floor) (F) |

| Climbing up on a bookcase (F) |

| Jumping on the edge of the bed (F) |

| Reaching to pick up a steak knife (C) |

| Reaching to pick up adult scissors (sharp/pointy) (C) |

| Holding a sharp fireplace poker (C) |

Note. Hazards showed risks for poison (P), burns (B), falls (F), and cuts (C).There were variations in photos for each activity to avoid identical photos being presented across sessions.

To generate a hazard understanding score, once the child completed sorting the photos, the research assistant asked the following question about the pictures in the Not Okay box (randomized order): “Tell me why the child should not be doing this?” The research assistant was allowed to prompt the child once if the child failed to provide a clear answer (e.g., “Tell me more”; “What else can you tell me about that.”). The children’s answers were audio recorded and later coded to provide knowledge and understanding scores both pre- and postintervention (cf. Schell et al., 2015).

Contrived Hazards Room

Two contrived hazards (CH) rooms provided children a naturalistic setting for purposes of measuring the child’s hazard interactions pre- and postintervention; each child was randomly assigned to one room at pre and the other was used at post. As in past research, these rooms were set up to look like offices and had video cameras unobtrusively located in the ceiling. They contained “contrived hazards” to provide children with the opportunity to interact with items that appeared to be similar to those that typically exist in the home (cf. Morrongiello & Dawber, 1998). However, the hazard-like items in these rooms were modified so that they no longer posed a safety threat to children (e.g., a lighter with no lighter fluid, a pair of scissors that has been glued shut). The hazards present in this room covered the same hazard categories as in the storybook (burns, cuts, falls, and poisonings). In each room, the same types of injuries were represented, but different hazards were used to represent each type, and there were also nonhazardous items; a listing of items in each room is given in Table IV. Comparing the number of hazards children touched before and after receiving the intervention indicated if risk behaviors decreased based on exposure to the intervention.

| CH Room 1 . | CH Room 2 . |

|---|---|

| Medicine container (pills inside) | Medicine container (pills inside) |

| Paper boxes with mobile above | Paper boxes with balloons above |

| Electrical plug (extension cord) | Electrical plug (extension cord) |

| Makeup container | Makeup container |

| Perfume container | Perfume container |

| Candle | Candle |

| Adult scissors | Adult scissors |

| Coffee mug with liquid | Coffee mug with liquid |

| Matches | Lighter |

| Sharp knife | Sharp knife |

| Whiteout | Whiteout |

| Mop and Shine spray bottle | Floor cleaner spray bottle |

| Windex spray bottle (blue liquid) | Windex spray bottle (pink liquid) |

| Sandwich maker (light on) | Kettle (light on) |

| Step ladder (decorative wall hanging above it) | Step ladder (teddy bear wall hanging above it) |

| Envelope opener | Envelope opener |

| CH Room 1 . | CH Room 2 . |

|---|---|

| Medicine container (pills inside) | Medicine container (pills inside) |

| Paper boxes with mobile above | Paper boxes with balloons above |

| Electrical plug (extension cord) | Electrical plug (extension cord) |

| Makeup container | Makeup container |

| Perfume container | Perfume container |

| Candle | Candle |

| Adult scissors | Adult scissors |

| Coffee mug with liquid | Coffee mug with liquid |

| Matches | Lighter |

| Sharp knife | Sharp knife |

| Whiteout | Whiteout |

| Mop and Shine spray bottle | Floor cleaner spray bottle |

| Windex spray bottle (blue liquid) | Windex spray bottle (pink liquid) |

| Sandwich maker (light on) | Kettle (light on) |

| Step ladder (decorative wall hanging above it) | Step ladder (teddy bear wall hanging above it) |

| Envelope opener | Envelope opener |

Note. For items in each room that shared the same label (e.g., chair, paper boxes, etc.) the two samples differed in visual features (e.g., color, size).

| CH Room 1 . | CH Room 2 . |

|---|---|

| Medicine container (pills inside) | Medicine container (pills inside) |

| Paper boxes with mobile above | Paper boxes with balloons above |

| Electrical plug (extension cord) | Electrical plug (extension cord) |

| Makeup container | Makeup container |

| Perfume container | Perfume container |

| Candle | Candle |

| Adult scissors | Adult scissors |

| Coffee mug with liquid | Coffee mug with liquid |

| Matches | Lighter |

| Sharp knife | Sharp knife |

| Whiteout | Whiteout |

| Mop and Shine spray bottle | Floor cleaner spray bottle |

| Windex spray bottle (blue liquid) | Windex spray bottle (pink liquid) |

| Sandwich maker (light on) | Kettle (light on) |

| Step ladder (decorative wall hanging above it) | Step ladder (teddy bear wall hanging above it) |

| Envelope opener | Envelope opener |

| CH Room 1 . | CH Room 2 . |

|---|---|

| Medicine container (pills inside) | Medicine container (pills inside) |

| Paper boxes with mobile above | Paper boxes with balloons above |

| Electrical plug (extension cord) | Electrical plug (extension cord) |

| Makeup container | Makeup container |

| Perfume container | Perfume container |

| Candle | Candle |

| Adult scissors | Adult scissors |

| Coffee mug with liquid | Coffee mug with liquid |

| Matches | Lighter |

| Sharp knife | Sharp knife |

| Whiteout | Whiteout |

| Mop and Shine spray bottle | Floor cleaner spray bottle |

| Windex spray bottle (blue liquid) | Windex spray bottle (pink liquid) |

| Sandwich maker (light on) | Kettle (light on) |

| Step ladder (decorative wall hanging above it) | Step ladder (teddy bear wall hanging above it) |

| Envelope opener | Envelope opener |

Note. For items in each room that shared the same label (e.g., chair, paper boxes, etc.) the two samples differed in visual features (e.g., color, size).

Take Home Binders

In addition to the storybook, each family was provided with a binder that included instructions, a reading log, and velcro stickers. The reading log provided an account about length of reading sessions (in minutes). Stickers indicating “healthy” (green) and “not healthy” (red) for Healthy Apple and “safe” (green) and “not safe” (red) for Careful Puppy were used to engage the child in reading sessions and increase their interaction with the material.

Questionnaire Measures

The Family Information Sheet collected demographic information from families including their ethnicity, household income, and parent education. A Postintervention Questionnaire assessed the mother’s feedback on the storybook. Items included whether she and her child enjoyed reading the book together (yes or no: Did you enjoy reading the book with your child? Did your child enjoy reading the book with you?), the extent of the child’s level of understanding (1 = not at all, 5 = very well), and what she believed was the child’s favorite part of the storybook.

Procedure

Lab sessions took place at the university in a suburban, southwestern region of Ontario, Canada. During each visit, research assistants followed a structured script to ensure uniformity in testing procedures across participants and testers. Until they received their storybook, the mother and child were blind as to the condition to which they were assigned.

At the first lab visit, a research assistant obtained consent and then explained the contrived hazards room to the mother. It was emphasized that she should complete the questionnaire during this time with her child in the room. If the child asked her to play, the mother was instructed to say she had paperwork to do and to direct the child to play with some toys that were in the corner of the room (e.g., books, blocks, pinwheel). The mother and child were video recorded for 10 min (i.e., preintervention measure of risky behavior). After the CH room task was completed, a research assistant completed the photo-sorting task with the child (i.e., preintervention measure of knowledge and understanding) in one room, whereas another research assistant in a separate room gave the storybook to the mother (depending on condition) and explained the take home binder, including demonstrating how to record information. Finally, the research assistant provided mothers with a demonstration on how to read the storybook and how to use the index card to guide their reading sessions; mothers then demonstrated their understanding by reading the book to the research assistant, asking any questions as they did so. Mothers were asked to read the storybook with their child for at least 10 min a day, four times a week.

After 4 weeks, participants attended a second lab visit. The child and mother waited for 10 min in a new contrived hazards room (i.e., postintervention measure of risky behavior); to make the mother somewhat distracted as in visit 1, the parent completed the Postintervention Questionnaire during this period. The child then completed the photo-sort task (i.e., postintervention measure of knowledge and understanding). At the conclusion, children chose a small gift and mothers received a $20 gift card for their participation.

Data Coding and Reliability and Intervention Fidelity

Audio Coding

For the photo-sort task, each correctly assigned risk photo (i.e., Not Okay To Do injury-risk behaviors) was assigned one point, resulting in a possible total correct knowledge score ranging from 0 to 27. This Knowledge Score was then converted to a percent correct for analysis.

The Understanding Score was based on coding children’s explanations for not doing a risk behavior. Scores were assigned based on the depth of understanding of the injury issue and ranged between 1 and 6, with higher scores indicating greater understanding: 1 = no response; 2 = response was unrelated to safety (e.g., It could make a mess); 3 = unclear response about safety (e.g., Something could be hot); 4 = general safety concern (e.g., She could get hurt doing that); 5 = specific safety concern (e.g., He might touch the hot oven and get hurt); or 6 = understanding the specific injury consequence of touching the hazard (e.g., He could burn his hand if he touched that because it could be very hot). Scores were summed and then divided by the number of photos to yield an average understanding score.

Raters were unaware of group assignment or time point when audio coding. Inter-rater reliability averaged 92% agreement for coding children’s responses, based on 25% of the sample being coded independently by two undergraduate students. The data of the primary coder were analyzed.

Contrived Hazard Room Coding

The coding system was the same used in previous studies and it measured touches of a hazard by the child (cf. Morrongiello & Dawber, 1998; Morrongiello et al., 2010; Schell et al., 2015). Raters were unaware of group assignment or time point when coding. Inter-rater reliability averaged 94% agreement, based on 25% of the sample being coded independently by two undergraduate students. The data of the primary coder were analyzed.

Fidelity Check

Because the storybook intervention was delivered to the child by the parent in the home, we conducted a home visit at which we unobtrusively audio recorded the parent and child reading the book together; this occurred 1 week after the lab visit. This recording was then coded to determine if the parent was following the steps outlined on the index card (see Materials) for each unsafe (unhealthy) picture; inter-rater reliability was 96% agreement based on 25% of the sample being coded independently by two undergraduate students. Averaging across pictures, the overall fidelity score reached 94% accuracy. Hence, it seemed that parents were reading the storybook as intended.

In terms of if they followed through on frequently reading the storybook with their child, we estimated that if each reading took about 10 min and they did this four times/week then the average number of minutes reading the book should be at least 160 min over the 4-week time. Based on parent reports on the binder sheets, the findings suggest that compliance was good (M = 163.45 min, SD = 18.22).

Data Screening and Analytic Approach

Using SPSS, descriptive and parametric statistics were applied to characterize the data and compare the pattern of results across conditions, including analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests. Preliminary data checking procedures were applied (Howell, 2007). For all analyses, Levene’s assumptions were non-significant, indicating no violation in the equality of variance. Outliers were removed based on Cook’s Distance, specifically, if Cook’s D was greater than 3.3 (Cook, 1977); only 2 outlier scores were removed for the Understanding analysis (see Understanding Injury Risk section in Results). Normality of distribution of variables and residuals was explored for each analysis (e.g., skewness, kurtosis), and no violations to normality were identified. Although no adverse effects were formally assessed for, none were spontaneously reported by any participants.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Groups

Demographic information for each group and the total sample is given in Table I. Group comparisons for each category were made using either one-way ANOVA with group as a between-participant factor (continuous variable) or chi square tests of association (categorical variables), and no significant differences were found. Thus, the randomization was effective in creating two groups with comparable demographic characteristics.

Parent Ratings of the Careful Puppy Storybook

Data collected from the Postintervention Questionnaire indicated that mothers thought the storybook was an effective teaching tool. The majority (86%) of mothers reported enjoying reading the storybook with their child and that their child enjoyed it as well (88%). Most mothers (96%) rated their child’s understanding of the book by the end as very good. The majority of mothers (89%) reported their child’s favorite part of the book was placing the safe/not safe stickers on each page. Overall, maternal ratings suggest that the storybook was developmentally appropriate (engaging, enjoyable, understandable) for children ranging in age from 3.5 to 5.5 years.

Knowledge of Hazards

For each child, a proportion correct score was calculated based on their photo sort performance at pre- and posttest (i.e., total number of risk photos the child rated as Not Okay To Do divided by 27). An ANCOVA was applied to the posttest data with group (2: intervention, control) as a between-participant factor and pretest score, age (months), and sex entered as covariates.

A significant effect of group was found, F(1, 54) = 7.69, p < .01, ηp2 = 0.13, 90% CI [0.02, 0.26]; for a discussion of why 90% CI is preferred to 95% CI for ηp2 see Steiger (2004). As shown in Table V, children in the intervention group showed significantly greater knowledge at posttest than those in the control group, rating significantly more hazard photos as things they should not do.

Proportion Correct Hazard Identification Knowledge, Extent of Understanding of Injury Risk Associated With Hazards (Score Range: 1–6), and Number of Hazard Touches in the Contrived Hazard Room for Pre- and Postintervention Periods for Intervention (n = 29) and Control (n = 30) Groups

| Score . | Group . | Preintervention . | Postintervention . |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) . | M (SD) . | ||

| Knowledgea | Intervention | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.84 (0.23) |

| Control | 0.62 (0.14) | 0.63 (0.25) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.13, 90% CI [0.02, 0.26] | ||

| Understandinga | Intervention | 3.13 (1.11) | 5.36 (0.67) |

| Control | 3.76 (1.31) | 2.77 (0.80) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.19, 90% CI [0.04, 0.32] | ||

| Hazard touchesa | Intervention | 10.00 (4.42) | 7.69 (5.31) |

| Control | 12.83 (8.91) | 13.97 (8.89) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.51, 90% CI [0.35, 0.62] |

| Score . | Group . | Preintervention . | Postintervention . |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) . | M (SD) . | ||

| Knowledgea | Intervention | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.84 (0.23) |

| Control | 0.62 (0.14) | 0.63 (0.25) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.13, 90% CI [0.02, 0.26] | ||

| Understandinga | Intervention | 3.13 (1.11) | 5.36 (0.67) |

| Control | 3.76 (1.31) | 2.77 (0.80) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.19, 90% CI [0.04, 0.32] | ||

| Hazard touchesa | Intervention | 10.00 (4.42) | 7.69 (5.31) |

| Control | 12.83 (8.91) | 13.97 (8.89) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.51, 90% CI [0.35, 0.62] |

Significant effect of Group at posttest, p < .01, with age, sex and pre scores as covariates.

Proportion Correct Hazard Identification Knowledge, Extent of Understanding of Injury Risk Associated With Hazards (Score Range: 1–6), and Number of Hazard Touches in the Contrived Hazard Room for Pre- and Postintervention Periods for Intervention (n = 29) and Control (n = 30) Groups

| Score . | Group . | Preintervention . | Postintervention . |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) . | M (SD) . | ||

| Knowledgea | Intervention | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.84 (0.23) |

| Control | 0.62 (0.14) | 0.63 (0.25) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.13, 90% CI [0.02, 0.26] | ||

| Understandinga | Intervention | 3.13 (1.11) | 5.36 (0.67) |

| Control | 3.76 (1.31) | 2.77 (0.80) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.19, 90% CI [0.04, 0.32] | ||

| Hazard touchesa | Intervention | 10.00 (4.42) | 7.69 (5.31) |

| Control | 12.83 (8.91) | 13.97 (8.89) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.51, 90% CI [0.35, 0.62] |

| Score . | Group . | Preintervention . | Postintervention . |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) . | M (SD) . | ||

| Knowledgea | Intervention | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.84 (0.23) |

| Control | 0.62 (0.14) | 0.63 (0.25) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.13, 90% CI [0.02, 0.26] | ||

| Understandinga | Intervention | 3.13 (1.11) | 5.36 (0.67) |

| Control | 3.76 (1.31) | 2.77 (0.80) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.19, 90% CI [0.04, 0.32] | ||

| Hazard touchesa | Intervention | 10.00 (4.42) | 7.69 (5.31) |

| Control | 12.83 (8.91) | 13.97 (8.89) | |

| Effect size | ηp2 = 0.51, 90% CI [0.35, 0.62] |

Significant effect of Group at posttest, p < .01, with age, sex and pre scores as covariates.

For the intervention group, the relationship between the number of minutes spent reading the book (M = 163.45, SD = 18.22) and knowledge scores was assessed. A moderate correlation was found between knowledge scores and number of minutes reading the book, r = .41, p < .05. Thus, higher exposure to the storybook led to children having greater gains in knowledge.

Understanding Injury Risk

For each child, an average understanding score was calculated based on their explanations for not doing a risk behavior in the photo sort task at pre- and posttest, with higher scores (range from 1 to 6) indicating greater understanding of injury risk associated with different home hazards. An ANCOVA was applied to the posttest data with group (2: intervention, control) as a between-participant factor and pretest score, age (months), and sex as covariates. As shown in Table V, there were significant group differences at posttest (F [1, 50] = 10.40, p < .01; ηp2 = 0.19, 90% CI [.04, .32]). Those in the intervention group showed significantly greater understanding of home hazards compared with those in the control group.

Interactions With Hazards

Based on their frequency of touching hazards in the contrived hazards room, children were assigned a score for pre- and postintervention. An ANCOVA was applied to these posttest data with group (2: intervention, control) as a between-participant factor and pretest score, age (months), and sex as covariates.

A significant effect of group was found, F (1, 54) = 56.71, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.51, 90% CI [0.35, 0.62]. As shown in Table V, children in the intervention group made fewer hazard interactions at posttest than those in the control group.

Discussion

Epidemiological data indicate that young children are at particular risk for injury in their homes (WHO, 2008). Hence, many past safety interventions have sought to improve the home safety practices of parents (Gielen et al., 2002; Morrongiello et al., 2013; Watson et al., 2005). However, interventions that improve preschoolers' understanding of injury risks in the home are also needed because many injuries occur when they interact with hazards while not being directly supervised (Morrongiello et al., 2001, 2009). The results of this study demonstrate that a storybook about home safety can effectively address this need.

Exposure to the storybook resulted in children not only identifying more hazards but also showing improved understanding of the injury risks associated with these. The latter is an important outcome because past research has found that greater understanding predicts less risk taking in young children (Morrongiello et al., 2014a). Research in the education domain reveals that creating opportunities for inductive reasoning promotes children’s depth of understanding and increases their generalization of knowledge to new situations, which is key for applying their new knowledge in novel ways (Busch et al., 2018; Klauer & Phye, 2008). Assimilating this approach into the current intervention, parents were instructed to provide explanations that emphasized cause-effect relations so that children would realize how interactions with hazards could result in injuries. Thus, the goal was not simply to have children identify specific hazardous behaviors to avoid, but to have them understand the underlying reason why so they would generalize this knowledge and realize what could happen from failing to do so when confronting similar hazards in new situations. The success of this approach was reflected in children not only showing greater explanations in postintervention interviews but applying this knowledge and making fewer hazard interactions in the contrived hazard situation. This behavioral change is noteworthy because young children sometimes show increased safety knowledge after exposure to an intervention, but this does not translate into reductions in risk behaviors (e.g., Schwebel et al., 2012).

A number of unique aspects of the intervention may have contributed to its success. In contrast to previous interventions for preschool children that have focused on only one type of injury (e.g., Himle et al., 2004; Loescher et al., 1995; Sinelnikov et al., 2005; Tripp et al., 2000), the current intervention addressed the broad range of types of injuries that young children experience in the home (e.g., poisoning, burns, drowning, and falls; WHO, 2008). This diversity in content may have helped to maintain children’s interest (Son et al, 2011). Unlike past interventions, delivery did not require specialized or intense training by facilitators and there was no required number of sessions. Rather, the material was delivered by parents, with no specialized training needed, and on whatever schedule they deemed best for their child. The Careful Puppy Saves the Day book capitalized on children’s interest in storybooks, particularly those with brightly colored pictures (Brookshire et al., 2002). Moreover, having parents deliver the intervention book allowed them to draw on their knowledge of their own child’s individual needs (e.g., attention limits, language and conceptual understanding, times when they are most alert and ready to learn) so they could tailor delivery to maximize their child’s readiness to learn. Creating the opportunity for tailoring is important because this can enhance the positive impact of an intervention (e.g., Hilliard et al., 2016). Finally, research on ways to promote young children’s assimilation of new knowledge highlights the benefit of blending play with learning activities (Samuelsson & Carlsson, 2008). This was reflected in the current intervention by having children place stickers on each page to indicate their judgments (safe, not safe), which parents rated as the child’s most enjoyable aspect of reading the book together. Hence, the design of the intervention, as well as the nature of how it was delivered and by whom, all are factors that distinguished it from past safety-promotion efforts and probably contributed to its positive impact on children’s knowledge and safety practices.

These findings have a number of potential practical applications. The use of a storybook that provides interactive learning opportunities about safety to children is a resource that could be provided, for example, by pediatricians to parents during well-child visits or when parents visit emergency departments seeking treatment for a child’s injury. It is common practice for teachers to read books during circle time in daycares and preschool classes and this book could promote engagement and attention by involving children in doing the sticker activities and actively discussing their opinions about home injury risks. Additionally, parallel versions of storybooks could be created to target other injury risk situations that occur outside the home (e.g., playgrounds, pools/beaches) or particular types of injury (e.g., falls) that children are at high risk of experiencing across a number of situations (Morrongiello & Corbett, 2016). Thus, this storybook could serve as a template for designing other books about injury risks and prevention.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this research significantly advances the field, there are limitations that merit consideration when planning future research. First, the sample is relatively homogeneous in demographic characteristics and some information about the sample was not obtained (e.g., first or later born, hours child was in daycare, hours parent was working outside the home). Extending the research to assess if the same positive effects are realized with a more demographically diverse sample is essential to determine generalizability. Related to this, all the parent participants were mothers. Hence, one cannot say if the same positive effects would be realized if fathers were to deliver the intervention. Second, although we conducted a fidelity check by doing a home visit at a time when parents were reading the storybook to their child, in the future it would be useful to video record all of these reading exchanges. This would enable us to assess what promotes learning and the extent to which this is driven by parents or their children. For example, do parents question their child in targeted ways to assess their learning and identify their child’s knowledge gaps, or do children pose questions that enable parents to do so? Applying observational and coding protocols used in book sharing research could be helpful (Luo & Tamis-LeMonda, 2017; Nyhout & O’Neill, 2013). Finally, although including a long-term outcome to measure the sustainability of the improvements in children’s performance was beyond the scope of this study, doing so in the future is an important next step in evaluating this intervention. This could reveal, for example, whether periodic booster sessions are necessary for sustainability and/or generalization of learning. Tracking injury rates before and after the intervention would be another way to assess impact and longer-term effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their thanks to the children and parents who participated in this research and the staff at the Child Development Research Unit for assistance with conducting this research. Reprint requests can be directed to [email protected].

Funding

This research was supported by grants to the first author from the Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council of Canada. The first author was supported by a Canada Research Chair award.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). (