-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tatiana Lund, Maria Pavlova, Madison Kennedy, Susan A Graham, Carole Peterson, Bruce Dick, Melanie Noel, Father– and Mother–Child Reminiscing About Past Pain and Young Children’s Cognitive Skills, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 46, Issue 7, August 2021, Pages 757–767, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab006

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objective Painful experiences are common, distressing, and salient in childhood. Parent-child reminiscing about past painful experiences is an untapped opportunity to process pain-related distress and, similar to reminiscing about other distressing experiences, promotes children’s broader development. Previous research has documented the role of parent-child reminiscing about past pain in children’s pain-related cognitions (i.e., memories for pain), but no study to date has examined the association between parent-child reminiscing about past painful experiences and children’s broader cognitive skills. Design and Methods One hundred and ten typically developing four-year-old children and one of their parents reminisced about a past painful autobiographical event. Children then completed two tasks from the NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery, the Flanker Inhibitory Control & Attention Test and the Picture Sequence Memory Test, to measure their executive function and episodic memory, respectively. Results Results indicated that the relation between parental reminiscing style and children’s executive function was moderated by child sex, such that less frequent parental use of yes-no repetition questions was associated with boys’ but not girls’, greater performance on the executive function task. Children displayed greater episodic memory performance when their parents reminisced using more explanations. Conclusions The current study demonstrates the key role of parent-child reminiscing about pain in children’s broader development and supports the merging of developmental and pediatric psychology fields. Future longitudinal research should examine the directionality of the relation between parent-child reminiscing about past pain and children’s developmental outcomes.

Introduction

Young children frequently encounter painful events in their everyday life as they grow and develop (Noel et al., 2018). These commonly experienced painful events range from minor injuries resulting in bumps and bruises to venipunctures, vaccine injections, and surgeries. These painful experiences are salient, distressing, and remembered long after the pain is over (Noel et al., 2012). Children who develop negatively biased pain memories (i.e., recalling more pain than was initially reported) are more likely to experience greater pain and distress during future painful experiences (for a review see Noel et al., 2017). In addition to individual (e.g., anxiety, age) factors (Noel et al., 2012), how mothers and fathers talk to young children about past painful experiences shapes how pain is later remembered (Noel et al., 2019). Young children are capable of recalling past painful experiences (Jaaniste et al., 2016) and talking about them (Job et al., 2005), yet past pain rarely becomes a topic of parent–child conversations (Craig et al., 2006). This represents a missed opportunity to process pain-related distress, coconstruct meaning, and discuss coping strategies to prepare children for future pain experiences and foster their coping and development.

This study is grounded in a socio-cultural theory of development (Vygotsky, 1980), which posits that socio-linguistic interactions between parents and children shape children’s development. Nelson and Fivush (2004) adapted Vygotskian theory in their social cultural developmental theory to examine children’s development of autobiographical memory in the context of parent–child reminiscing about past events, which directly informs this study. Developmental literature on reminiscing about past autobiographical events has identified two distinct parental reminiscing styles. Elaborative reminiscing, characterized by parental use of open-ended questions containing new information and language rich in emotional content, is associated with optimal socio-emotional and cognitive outcomes in young children (Fivush et al., 2006; Salmon & Reese, 2016), including autobiographical memory for painful injuries (Peterson et al., 2007). In contrast, a topic-switching style, characterized by parental repetitions of close-ended questions, providing few additional details, and lower levels of support of children’s autonomy, has been associated with poorer developmental outcomes (e.g., poorer autobiographical memory) (Cleveland & Reese, 2005; Sales et al., 2003). Although recent research demonstrated that mother– and father–child reminiscing style and content (i.e., higher proportions of elaborations and emotional words) are linked to positive biases in children’s memories for pain (i.e., recalling less pain than was initially reported) following surgery (Noel et al., 2019), less is known about how parent–child reminiscing about painful events is related to children’s broader cognitive skills. Such knowledge would shed light on the potential benefits of parent–child reminiscing about past painful events which in turn could foster parents’ willingness to process these frequent, salient, and memorable painful experiences. This study aimed to fill that gap.

A foundational component of autobiographical memory is episodic memory (EM), which represents a core cognitive domain posited to emerge during the preschool years (Scarf et al., 2013). EM is responsible for the “storage of unique events or experiences encoded in a time-specific manner” and serves as the “building blocks for cognitive growth during development” (Weintraub et al., 2013, p. S55). Given the distressing, salient, and memorable nature of painful events (Peterson, 2015), reminiscing about these autobiographical events may serve to bolster children's foundational EM skills. Reminiscing about pain may also influence children s executive function (EF) skills (e.g.,inhibitory control and attention). Elaborative reminiscing provides children with the opportunity to practice focusing their attention on what is discussed (Salmon & Reese, 2016) by enabling a “shared reference of attention” (Fivush et al., 2006, p. 1580)). In doing so, parent–child reminiscing about past painful events may serve as an opportunity for children to practice and enhance their attentional skills. In terms of inhibitory control, by discussing past pain, a phenomenon generally avoided by children and parents (Craig et al., 2006), parents may be controlling the automatic response of switching the topic.

Furthermore, fathers have not commonly been included in research on parent–child reminiscing (Salmon & Reese, 2016). A handful of studies have compared father– and mother–child reminiscing (Fivush et al., 2000; Haden et al., 1997; Zaman & Fivush, 2013) yielding equivocal findings. In a recent examination of parent–child reminiscing about past painful events, in which young children reminisced with their mothers and fathers about a past tonsillectomy, differences in reminiscing were found as a function of parent role and child sex (Noel et al., 2019). Specifically, when reminiscing about the past surgery, fathers, as compared with mothers, used more explanations with their children. When reminiscing with boys versus girls, mothers used more negative emotion words when compared with fathers. Although mothers and fathers differed in reminiscing with children about past painful events, it did not influence children’s pain memory biases. In terms of child sex differences, parents use more elaborations and talk more about coping with boys than with girls, when reminiscing about past painful nonsurgical events (Pavlova et al., 2019). Little is known about whether mothers and fathers reminisce differently about other past painful events and whether they have differential influences on children’s broader cognitive skills.

To fill these gaps in the literature, this study examined the relationship between mother– and father–child reminiscing about past painful events and two core cognitive skills (i.e., EM and EF, specifically attention and inhibitory control). Considering findings that parents reminisce more elaboratively with their children about highly stressful and negative events than positive events (Ackil et al., 2003; Sales et al., 2003) and that elaborative reminiscing is positively associated with children’s cognitive development (Fivush et al., 2006; Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Salmon & Reese, 2016) it was hypothesized that children whose parents reminisced in elaborative ways would demonstrate greater performance on the cognitive outcomes. We also examined the moderating role of child sex and parent role in the relationships between parent reminiscing style about past painful events and children’s cognitive outcomes. Based on equivocal findings of parent role differences on broader cognitive outcomes (Fivush et al., 2000; Haden et al., 1997; Zaman & Fivush, 2013), no specific hypotheses on the effect of child sex and parent role on cognitive outcomes were made.

Materials and Methods

Participants

One hundred and ten typically developing 4-year-old children (Mage= 54.5 months, SD = 3.7 months, 55% female) and one of their parents (51% fathers) were recruited from an existing database of families in Western Canada who provided their consent and expressed interest in being contacted for research purposes (see Table I for sociodemographic characteristics of the sample). Children and their parents were eligible to participate if (a) the child was 4 years old; (b) one of their parents consented to participate; (c) both the child and parent could understand and speak English. Children were excluded if they had a parent-reported language delay and/or a developmental disorder. The institution’s research ethics board approved this study. This study aimed to examine the association between parent–child reminiscing about past painful events and children’s cognitive skills (i.e., EM and EF). Parent–child reminiscing narratives of this sample are included in analyses of a broader research project that examined the role of parent–child reminiscing in socialization of children’s prosocial behaviors and empathy toward another person’s pain (Pavlova et al., accepted).

| Sociodemographic characteristic . | N = 110 . |

|---|---|

| Age in months, M (SD) | 54.48 (3.75) |

| Child sex (female), % (N) | 60 (55) |

| Parent role (father), % (N) | 49 (54) |

| Child ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Black | 0.9 (1) |

| Chinese | 1.8 (2) |

| Filipino | 0.9 (1) |

| Latin American | 1.8 (2) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 74.1 (83) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 17.9 (20) |

| Other | 1.8 (2) |

| Parent ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Aboriginal | 0.9 (1) |

| Black | 1.7 (2) |

| Chinese | 5.2 (6) |

| Filipino | 1.7 (2) |

| Latin American | 4.3 (5) |

| South Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 80 (92) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 4.3 (5) |

| Parent highest level of education, % (N) | |

| High school or less | 6 (7) |

| Vocational school/some college | 23 (25) |

| College degree | 52 (57) |

| Graduate school | 19 (21) |

| Work status, % (N) | |

| Full time | 68 (75) |

| Part time | 17 (19) |

| Not employed | 15 (16) |

| Household annual income, % (N) | |

| <$70,000 | 15 (16) |

| >$70,000 | 85 (94) |

| Parent marital status, % (N) | |

| Married | 86 (94) |

| Common law | 6 (7) |

| Single | 4 (4) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (3) |

| Do not want to answer | 1 (1) |

| Sociodemographic characteristic . | N = 110 . |

|---|---|

| Age in months, M (SD) | 54.48 (3.75) |

| Child sex (female), % (N) | 60 (55) |

| Parent role (father), % (N) | 49 (54) |

| Child ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Black | 0.9 (1) |

| Chinese | 1.8 (2) |

| Filipino | 0.9 (1) |

| Latin American | 1.8 (2) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 74.1 (83) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 17.9 (20) |

| Other | 1.8 (2) |

| Parent ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Aboriginal | 0.9 (1) |

| Black | 1.7 (2) |

| Chinese | 5.2 (6) |

| Filipino | 1.7 (2) |

| Latin American | 4.3 (5) |

| South Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 80 (92) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 4.3 (5) |

| Parent highest level of education, % (N) | |

| High school or less | 6 (7) |

| Vocational school/some college | 23 (25) |

| College degree | 52 (57) |

| Graduate school | 19 (21) |

| Work status, % (N) | |

| Full time | 68 (75) |

| Part time | 17 (19) |

| Not employed | 15 (16) |

| Household annual income, % (N) | |

| <$70,000 | 15 (16) |

| >$70,000 | 85 (94) |

| Parent marital status, % (N) | |

| Married | 86 (94) |

| Common law | 6 (7) |

| Single | 4 (4) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (3) |

| Do not want to answer | 1 (1) |

| Sociodemographic characteristic . | N = 110 . |

|---|---|

| Age in months, M (SD) | 54.48 (3.75) |

| Child sex (female), % (N) | 60 (55) |

| Parent role (father), % (N) | 49 (54) |

| Child ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Black | 0.9 (1) |

| Chinese | 1.8 (2) |

| Filipino | 0.9 (1) |

| Latin American | 1.8 (2) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 74.1 (83) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 17.9 (20) |

| Other | 1.8 (2) |

| Parent ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Aboriginal | 0.9 (1) |

| Black | 1.7 (2) |

| Chinese | 5.2 (6) |

| Filipino | 1.7 (2) |

| Latin American | 4.3 (5) |

| South Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 80 (92) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 4.3 (5) |

| Parent highest level of education, % (N) | |

| High school or less | 6 (7) |

| Vocational school/some college | 23 (25) |

| College degree | 52 (57) |

| Graduate school | 19 (21) |

| Work status, % (N) | |

| Full time | 68 (75) |

| Part time | 17 (19) |

| Not employed | 15 (16) |

| Household annual income, % (N) | |

| <$70,000 | 15 (16) |

| >$70,000 | 85 (94) |

| Parent marital status, % (N) | |

| Married | 86 (94) |

| Common law | 6 (7) |

| Single | 4 (4) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (3) |

| Do not want to answer | 1 (1) |

| Sociodemographic characteristic . | N = 110 . |

|---|---|

| Age in months, M (SD) | 54.48 (3.75) |

| Child sex (female), % (N) | 60 (55) |

| Parent role (father), % (N) | 49 (54) |

| Child ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Black | 0.9 (1) |

| Chinese | 1.8 (2) |

| Filipino | 0.9 (1) |

| Latin American | 1.8 (2) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 74.1 (83) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 17.9 (20) |

| Other | 1.8 (2) |

| Parent ethnicity, % (N) | |

| Aboriginal | 0.9 (1) |

| Black | 1.7 (2) |

| Chinese | 5.2 (6) |

| Filipino | 1.7 (2) |

| Latin American | 4.3 (5) |

| South Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| South East Asian | 0.9 (1) |

| White (Caucasian) | 80 (92) |

| Multi-Ethnic | 4.3 (5) |

| Parent highest level of education, % (N) | |

| High school or less | 6 (7) |

| Vocational school/some college | 23 (25) |

| College degree | 52 (57) |

| Graduate school | 19 (21) |

| Work status, % (N) | |

| Full time | 68 (75) |

| Part time | 17 (19) |

| Not employed | 15 (16) |

| Household annual income, % (N) | |

| <$70,000 | 15 (16) |

| >$70,000 | 85 (94) |

| Parent marital status, % (N) | |

| Married | 86 (94) |

| Common law | 6 (7) |

| Single | 4 (4) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (3) |

| Do not want to answer | 1 (1) |

Procedure

Potential participants were contacted by study staff via email or telephone and provided information about the study. Interested families were invited to the research laboratory for a 2-hr visit. Following the consent process, parents and children engaged in a structured narrative elicitation task. Parents were asked to recall a unique autobiographical event involving pain that their child had experienced (e.g., minor injuries, needle procedures). This painful event had to have occurred at least 1 month prior to their lab visit and been shared by the parent and child. Consistent with previous research, parents were instructed to talk as they typically would for as long as was natural for them (Sales et al., 2003). The researcher then left the room for the duration of the task. Parent–child narratives were recorded for later transcription and analysis. After the task, parents completed questionnaires in a separate room and children completed a subset of the NIH Toolbox (NIH-TB) Cognitive Battery (CB; Weintraub et al., 2013) with the researcher. NIH-TB-CB is validated for use with participants aged 3–85 years, and typically developing children were tested as a norm reference group (Weintraub et al., 2013). The NIH-TB-CB is psychometrically sound in its test–retest reliability, construct validity, and sensitivity to different levels of cognitive ability, for children 3–6 years of age. Parents reported their own and their child’s age, sex, ethnicity, and socio-demographic characteristics.

NIH-TB Custom Cognition Battery

A custom NIH-TB-CB was constructed to assess EF and EM. Age-corrected standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15) were used for all tasks, which compare the participant’s score to the NIH-TB normative sample for that age.

Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test

Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test measures EF by assessing inhibitory control and attention (Zelazo et al., 2013). During the task, a stimulus (fish facing left or right) is presented on the screen, and children press a button to indicate which way it is facing. If children get at least three correct in a practice sequence, they are shown five fish in a row over four trials and choose which way the middle fish is facing. The middle fish may be congruent (facing the same direction) or incongruent (facing the opposite direction) with the “flankers.” If a child scores ≥ 80% on the fish stimuli, 20 additional trials with arrows are presented. The task is automatically scored using a two-vector method incorporating accuracy and reaction time, where each vector ranges from 0 to 5 (Zelazo et al., 2013). Accuracy scores are based on the number of correct responses; if a child scores ≤ 80% on accuracy, their composite score equals their accuracy score. Otherwise, reaction time is calculated based on correct incongruent trials. A log (Base 10) transformation is applied to the median reaction time, which is then rescaled to range from 0 to 5. Accuracy and reaction time are combined for a total score ranging from 0 to 10, and the composite score is then converted to an age-corrected standard score.

Picture Sequence Memory Test

Picture Sequence Memory Test measures EM by assessing acquisition, storage, and recall of information (Bauer et al., 2013). In this task, a series of thematically related pictured objects and activities are presented. The pictures are then put in random order and children must place them one at a time in the correct order. Children complete three trials, each with an increasingly longer series of images (3–6 pictures). The score is derived from the cumulative number of correct adjacent pairs (e.g., in a 3-picture sequence, 1–2 and 2–3) in each trial (Bauer et al., 2013). Using item response theory, the sum of adjacent-pair scores is then converted to a theta score. Age-corrected standard scores were achieved by ranking the raw scores of participants, applying a normative transformation and rescaling the scores.

Narrative Coding Scheme

Parent–child narratives were transcribed verbatim and broken down into utterances defined as a conversational turn. Using a coding scheme adapted from developmental literature (Sales et al., 2003), previously used in parent–child pain narratives (Pavlova et al., 2019), utterances were coded on structure and content. For structural coding, parent utterances were coded as either open- or closed-ended questions containing new or repeating information, statements containing new or repeated information, or evaluations. For content coding, parent utterances were coded based on whether they contained explanations, emotion, coping, and pain words. In line with previous research, and to control for variations in narrative length, proportions of each code were calculated over the total number of codes for each code type. To avoid potential bias due to researcher-family interactions, narratives were coded by a researcher who did not conduct lab visits and had been trained on the coding scheme (M.P.). Twenty percent of narratives were then randomly chosen to be coded by an independent researcher, blind to the study hypotheses for reliability calculations. Interrater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa and was strong (McHugh, 2012) (85% structure; 80% content).

Children’s Communications Checklist-2

The Children’s Communications Checklist-2 (CCC-2) is a validated and reliable measure of communication skills in children aged 4–16 years (Bishop, 2006). The CCC-2 consists of 70 items assessing articulation, vocabulary, sentence structure, social aspects of language, and pragmatic aspects of children’s communication skills. Parents rate their children’s communication skills on a 4-point Likert scale (“less than once a week or never” to “several times [more than twice] a day [always]”). The general communication composite was the primary measure of language used as a covariate in the analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 26 (IBM Corp., 2019). Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to characterize the sample and key variables. Independent-sample t-tests were used to examine the differences in key variables as a function of child sex and parent role. Two-tailed bivariate correlational analyses were used to identify reminiscing codes that were significantly associated with children’s cognitive skills (i.e., EM and EF). Based on the correlational analyses, hierarchical regression models were conducted to examine the role of parent reminiscing codes in children’s cognitive skills. In line with previous research (Noel et al., 2019) and given that reminiscing is a language-based interaction (Eisenberg, 1985), communication skills were included in the regression analyses as a covariate.

The associations between all reminiscing codes and children’s cognitive skills were tested for moderation by child sex and parent role. Given the exploratory nature of the analyses, child sex and parent role were, first, entered as a covariate in the regression models. Interactions of child sex and parent role with narrative codes were entered in step 3 of the regression models; variables were centered prior to creating the interaction terms. Significant interactions were tested using Preacher and Hayes’ PROCESS procedure (Hayes, 2017). Bootstrapping using 5,000 samples was used in the moderation analyses. Sixty-eight participants were required to detect a medium effect size with 80% chance at .05 α level (G*Power; Faul et al., 2007).

Results

Missing Data

The final sample included 110 children–parent dyads that completed the narrative elicitation task. Seven children did not complete the Picture Sequence Task, nor the Flanker Task due to technical difficulties (N = 1), children’s refusal to complete tasks (N = 3), and distress at separation from parents (N = 3). One parent did not complete baseline questionnaires. The data were missing completely at random (Little’s Missing Completely at Random test, Χ2[70] = 43.68, p = .99). No data imputation was performed; list-wise deletion was used in the analyses. A series of omnibus analyses of variances did not reveal any significant differences on key variables as a function of NIH-TB tasks (non)completion, ps > .05.

Participants

The sample (N = 110 parent–child dyads, 49% fathers, 55% girls, Mage = 54.5 months) was predominantly white (71%) and middle-class (86%). Most parents were married (86%) and held a college degree (71%; Table I). Means and SDs of key variables are summarized in Table II. Children who participated in the study with their fathers (M = 107.71, SD = 14.67), versus mothers (M = 102.58, SD = 11.18), demonstrated better performance on the EF task, p = .048. Girls (M = 108.07, SD = 10.82), versus boys (M = 101.46, SD = 15.02), performed better on the EF task, p = .011. Children’s performance on NIH-TB tasks did not significantly differ as a function of other socio-demographic characteristics, ps > .05.

| Variable . | M . | SD . |

|---|---|---|

| NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task score, range: 51–137 | 107.80 | 25.06 |

| NIH Toolbox Flanker Task score, range: 62–134 | 105.12 | 13.22 |

| CCC-2 general communication composite, range: 34–124 | 78.73 | 14.55 |

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory question elaboration | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | 0.27 | 0.10 |

| Statement elaboration | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Memory question repetition | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no question repetition | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| Statement repetition | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Evaluation | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Negative emotion | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Explanation | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Coping | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| Pain | 0.59 | 0.22 |

| Variable . | M . | SD . |

|---|---|---|

| NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task score, range: 51–137 | 107.80 | 25.06 |

| NIH Toolbox Flanker Task score, range: 62–134 | 105.12 | 13.22 |

| CCC-2 general communication composite, range: 34–124 | 78.73 | 14.55 |

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory question elaboration | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | 0.27 | 0.10 |

| Statement elaboration | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Memory question repetition | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no question repetition | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| Statement repetition | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Evaluation | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Negative emotion | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Explanation | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Coping | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| Pain | 0.59 | 0.22 |

Note. N = 110. NIH Toolbox scores represent age-corrected standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15).

| Variable . | M . | SD . |

|---|---|---|

| NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task score, range: 51–137 | 107.80 | 25.06 |

| NIH Toolbox Flanker Task score, range: 62–134 | 105.12 | 13.22 |

| CCC-2 general communication composite, range: 34–124 | 78.73 | 14.55 |

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory question elaboration | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | 0.27 | 0.10 |

| Statement elaboration | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Memory question repetition | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no question repetition | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| Statement repetition | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Evaluation | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Negative emotion | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Explanation | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Coping | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| Pain | 0.59 | 0.22 |

| Variable . | M . | SD . |

|---|---|---|

| NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task score, range: 51–137 | 107.80 | 25.06 |

| NIH Toolbox Flanker Task score, range: 62–134 | 105.12 | 13.22 |

| CCC-2 general communication composite, range: 34–124 | 78.73 | 14.55 |

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory question elaboration | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | 0.27 | 0.10 |

| Statement elaboration | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Memory question repetition | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no question repetition | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| Statement repetition | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Evaluation | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Negative emotion | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Explanation | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Coping | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| Pain | 0.59 | 0.22 |

Note. N = 110. NIH Toolbox scores represent age-corrected standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15).

Painful Event Types

The painful events most commonly discussed by parents and children were everyday pain and needle-related pain, representing 58% and 19% of the sample, respectively. This was followed by illness-related pain (e.g., being sick with the flu; 10%), pain inflicted by another child or animal (7%), trauma-related pain (e.g., breaking a limb; 4%), and other (2%).

Parent–Child Reminiscing Codes and Children’s Cognitive Skills: Correlational Analyses

The associations between parent–child reminiscing codes and children’s performance on NIH-TB tasks are presented in Table III. Children’s EM was significantly correlated with the proportion of yes–no repetition questions (a code associated with topic-switching, nonadaptive reminiscing), such that more frequent use of yes–no repetition questions was associated with worse performance on the EM task, r = −.25, p = .011. Higher proportion of parent evaluations was correlated with better children’s performance on the EM task, r = .20, p = .043. More frequent parental use of explanations was associated with better children’s performance on the EM task, r = .27, p = .006. Parent use of yes–no repetition questions was negatively associated with children’s performance on the EF task, with higher proportions of yes–no repetition questions linked to worse EF, r = −.25, p = .010.

Correlations Between Parent–Child Reminiscing Codes and Children’s Performance on the NIH Toolbox Tasks

| . | NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task . | NIH Toolbox Flanker Task . |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory elaboration question | −0.09 | −0.11 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | −0.02 | 0.14 |

| Statement elaboration | −0.04 | 0.12 |

| Memory repetition question | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no repetition question | −0.25** | −0.25** |

| Statement repetition | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Evaluation statements | 0.20** | −0.06 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.01 | −0.14 |

| Negative emotion | −0.04 | −0.10 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.02 | −0.12 |

| Explanation | 0.27* | 0.11 |

| Coping | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Pain | −0.06 | 0.12 |

| . | NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task . | NIH Toolbox Flanker Task . |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory elaboration question | −0.09 | −0.11 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | −0.02 | 0.14 |

| Statement elaboration | −0.04 | 0.12 |

| Memory repetition question | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no repetition question | −0.25** | −0.25** |

| Statement repetition | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Evaluation statements | 0.20** | −0.06 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.01 | −0.14 |

| Negative emotion | −0.04 | −0.10 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.02 | −0.12 |

| Explanation | 0.27* | 0.11 |

| Coping | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Pain | −0.06 | 0.12 |

Note. N = 103. *p < .05 (two-tailed); **p < .01 (two-tailed).

Correlations Between Parent–Child Reminiscing Codes and Children’s Performance on the NIH Toolbox Tasks

| . | NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task . | NIH Toolbox Flanker Task . |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory elaboration question | −0.09 | −0.11 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | −0.02 | 0.14 |

| Statement elaboration | −0.04 | 0.12 |

| Memory repetition question | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no repetition question | −0.25** | −0.25** |

| Statement repetition | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Evaluation statements | 0.20** | −0.06 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.01 | −0.14 |

| Negative emotion | −0.04 | −0.10 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.02 | −0.12 |

| Explanation | 0.27* | 0.11 |

| Coping | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Pain | −0.06 | 0.12 |

| . | NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task . | NIH Toolbox Flanker Task . |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative structure codes | ||

| Memory elaboration question | −0.09 | −0.11 |

| Yes–no elaboration question | −0.02 | 0.14 |

| Statement elaboration | −0.04 | 0.12 |

| Memory repetition question | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Yes–no repetition question | −0.25** | −0.25** |

| Statement repetition | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| Evaluation statements | 0.20** | −0.06 |

| Narrative content codes | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.01 | −0.14 |

| Negative emotion | −0.04 | −0.10 |

| Neutral emotion | 0.02 | −0.12 |

| Explanation | 0.27* | 0.11 |

| Coping | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Pain | −0.06 | 0.12 |

Note. N = 103. *p < .05 (two-tailed); **p < .01 (two-tailed).

Parent–Child Reminiscing and Children’s Cognitive Skills: Hierarchical Regression Models

Based on the correlational analyses, two hierarchical regression models were constructed (Table IV). Covariates included children’s communication skills (Step 1); child sex and parent role (Step 2). If child sex and/or parent role were a significant predictor of children’s cognitive skills, their interactions with narrative codes were entered in the final step.

Parent–Child Reminiscing Codes and Children’s Cognitive Skills: Hierarchical Regression Models

| Criterion variable . | Step . | Predictor . | β . | ΔR2 . | Cumulative R2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic memory | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.16 | .037 | .062 | |

| Parent role | 0.11 | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .110** | .172** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.16 | ||||

| Evaluation statements | 0.12 | ||||

| Explanations | 0.28** | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .026 | .198 | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | −0.02 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.32 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × parent role | 0.04 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × child sex | 0.02 | ||||

| Explanations × parent role | −0.35 | ||||

| Explanations × child sex | 0.16 | ||||

| Executive function | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.26** | .101** | .125** | |

| Parent role | −0.19* | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .029 | .155** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.19 | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .063* | .218** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | 0.07 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.83** |

| Criterion variable . | Step . | Predictor . | β . | ΔR2 . | Cumulative R2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic memory | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.16 | .037 | .062 | |

| Parent role | 0.11 | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .110** | .172** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.16 | ||||

| Evaluation statements | 0.12 | ||||

| Explanations | 0.28** | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .026 | .198 | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | −0.02 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.32 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × parent role | 0.04 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × child sex | 0.02 | ||||

| Explanations × parent role | −0.35 | ||||

| Explanations × child sex | 0.16 | ||||

| Executive function | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.26** | .101** | .125** | |

| Parent role | −0.19* | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .029 | .155** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.19 | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .063* | .218** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | 0.07 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.83** |

Note. N = 103. *p < .05 and **p < .01. Episodic memory measured by the NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task. Executive function measured by the NIH Toolbox Flanker Task.

Parent–Child Reminiscing Codes and Children’s Cognitive Skills: Hierarchical Regression Models

| Criterion variable . | Step . | Predictor . | β . | ΔR2 . | Cumulative R2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic memory | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.16 | .037 | .062 | |

| Parent role | 0.11 | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .110** | .172** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.16 | ||||

| Evaluation statements | 0.12 | ||||

| Explanations | 0.28** | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .026 | .198 | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | −0.02 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.32 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × parent role | 0.04 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × child sex | 0.02 | ||||

| Explanations × parent role | −0.35 | ||||

| Explanations × child sex | 0.16 | ||||

| Executive function | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.26** | .101** | .125** | |

| Parent role | −0.19* | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .029 | .155** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.19 | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .063* | .218** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | 0.07 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.83** |

| Criterion variable . | Step . | Predictor . | β . | ΔR2 . | Cumulative R2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic memory | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.16 | .037 | .062 | |

| Parent role | 0.11 | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .110** | .172** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.16 | ||||

| Evaluation statements | 0.12 | ||||

| Explanations | 0.28** | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .026 | .198 | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | −0.02 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.32 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × parent role | 0.04 | ||||

| Evaluation statements × child sex | 0.02 | ||||

| Explanations × parent role | −0.35 | ||||

| Explanations × child sex | 0.16 | ||||

| Executive function | 1 | Communication skills | 0.16 | .024 | .024 |

| 2 | Child sex | 0.26** | .101** | .125** | |

| Parent role | −0.19* | ||||

| 3 | Narrative codes | .029 | .155** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions | −0.19 | ||||

| 4 | Interaction terms | .063* | .218** | ||

| Yes–no repetition questions × parent role | 0.07 | ||||

| Yes–no repetition questions × child sex | 0.83** |

Note. N = 103. *p < .05 and **p < .01. Episodic memory measured by the NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Task. Executive function measured by the NIH Toolbox Flanker Task.

Model 1: Children’s EM

Above and beyond the covariates, the proportion of yes–no repetition questions, evaluation statements, and parent use of explanations accounted for 11% of variance in children’s performance on the EM task, ΔF (3, 95) = 4.22, p = .008. Holding the covariates and narrative codes constant, interactions between the narrative codes and child sex/parent role did not account for a significant amount of variance, ΔF (6, 89) = 0.48, p = .822. The overall model accounted for 20% of variance in children’s performance on the EM task, F (12, 101) = 1.83, p = .055. Narrative codes’ beta weights suggested that more frequent use of explanations (β = 0.28, p = .005) was significantly related to children’s better performance on the EM task. Beta weights of interactions terms were not significant, ps > .05.

Model 2: Children’s EF

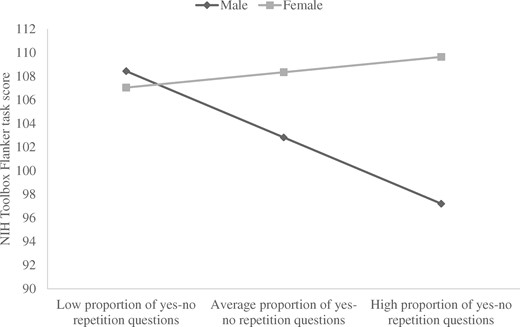

Parent role and child sex accounted for additional 10% of variance in children’s performance on the EF task, ΔF (2, 99) = 5.72, p = .004. Predictors’ beta weights suggested that children who participated in the study with their fathers, versus mothers, demonstrated better performance on the EF task (β = −0.19, p = .044). Girls compared with boys performed better on the task (β = 0.26, p = .008). Holding the covariates and the frequency of yes–no repetition questions constant, an interaction between child sex and the proportion of yes–no repetition questions and an interaction between parent role and the proportion of yes–no repetition questions accounted for an additional 6% of variance in children’s performance on the EF task, ΔF (2, 96) = 3.89, p = .024. The overall model accounted for 22% of variance in children’s performance on the EM task, F (6, 96) = 4.46, p = .001. Moderation analyses using the PROCESS procedure indicated that the interaction between child sex and the proportion of yes–no repetition questions was significant (children’s communication skills and parent role held constant), b = 57.91, 95% CI (16.28, 99.53), t = 2.76, p = .007. The interaction suggests lower proportions of yes–no repetition questions were associated with better boys’, but not girls’, performance on the EF task (Figure 1).

Interaction between child sex and the proportion of yes–no repetition questions.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between children’s cognitive abilities and parent–child reminiscing about past painful events, as well as moderating roles of parent role and child sex. The relationship between parental reminiscing style and children’s EF was moderated by child sex, such that less frequent parental use of yes–no repetition questions was significantly related to boys’ better performance on the EF task, whereas girls’ EF was not associated with parental use of yes–no repetition questions. This finding may demonstrate that boys may particularly benefit from an elaborative style of reminiscing about past painful events. Indeed, preschool-aged boys have been found to be more sensitive than girls to parental responding with respect to attentional abilities, but not other domains of cognitive function (Mileva-Seitz et al., 2015). That is, in a study of 3-year-old children and their parents, boys’, but not girls’, performance on a measure of attentional control varied as a function of parental sensitivity (characterized by parents’ emotional support, positive regard, reassurance, and praise) during two problem-solving tasks. It is possible that parental socialization factors such as parent response and reminiscing style may exert a greater influence on children with relatively less developed EF. Indeed, in this study, boys had significantly less developed EF compared with girls, a finding consistent with previous research (Berlin & Bohlin, 2002; Carlson & Moses, 2001). This study contributes more broadly to the literature on adaptive parent language and children’s EF (Bindman et al., 2013; Hughes & Devine, 2019).

Parents’ greater use of explanations was significantly associated with children’s better performance on the measure of EM. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis, and previous findings, that elements of a more elaborative parental reminiscing style (such as use of open-ended questions and providing new contextual information) were related to better developed attention, memory, and language (Fivush et al., 2006; Salmon & Reese, 2016); this includes children’s better autobiographical memory for painful injuries (Peterson et al., 2007). In an examination of 2- to 5-year-old children’s memory for injuries requiring an emergency department visit, children who recalled more accurate, complete, and detailed information about their hospital visit had parents who reminisced using an elaborative style (i.e., high scores on an “elaboration ratio,” a composite of elaborations and evaluations divided by elaborations, evaluations, and repetitions; Peterson et al., 2007). However, in this study, two other elements characteristic of elaborative parental reminiscing style, greater evaluations and fewer yes–no repetition questions, were not significantly associated with children’s EM. A possible explanation for these findings is that parental explanations may represent the most “prototypically elaborative” element of reminiscing, thereby promoting better memory. Indeed, autobiographical memory is bolstered by explanations of why and how events happened in the past (Salmon & Reese, 2016). In contrast, lower frequencies of yes–no repetition questions do not directly equate to more open-ended elaborative questions which are supportive of children’s memory. Similarly, evaluations (parental use of “yes” or “no” in response to children’s utterances) may create feelings of validation and support, but do not necessarily elicit or promote better memory. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating elaboration and support as two independent constructs, whereby the former, but not the latter, was related to children’s memory (Cleveland et al., 2007). Results indicated that children’s cognitive abilities were differentially associated with elements of parent reminiscing, depending on parent role and child sex. Specifically, children who reminisced with their fathers performed significantly better on the EF task. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have noted that fathers may play a particularly influential role in children’s cognition during the preschool years (Cabrera et al., 2007, 2020), which may be explained through fathers’ cognitive stimulation (e.g., engagement in narratives; Cabrera et al., 2020) and supportiveness (e.g., emotional support and elaboration; Cabrera et al., 2007). Overall, girls performed better on the EF task than did boys, a finding consistent with the literature on cognition in early childhood, that preschool-aged girls outperform boys on measures (e.g., go/no-go, stroop-like tasks) of inhibitory control (Berlin & Bohlin, 2002; Carlson & Moses, 2001).

Given the salient, distressing, and frequent nature of painful events in childhood (Noel et al., 2018; Peterson, 2015), these events comprise an untapped pool of opportunities for parents and children to reminisce. Indeed, in this sample, the most common painful events that children and parents reminisced about included everyday pain, followed by needle- and illness-related pain. Reminiscing about past painful events, in turn, provides a rich context for children to further practice and hone their cognitive skills (e.g., attention, memory) while interacting with their parents. To draw a comparison from the pediatric pain literature, immunizations have served as a powerful context within which to examine parent–child attachment during infancy (Hillgrove-Stuart et al., 2015). As children develop, pediatric pain contexts remain relevant and ripe for processing, as they have the potential to foster broader developmental outcomes in childhood. As such, this study supports the merging of the two fields, developmental psychology and pediatric pain. Commonly occurring painful experiences and parent–child interactions occurring on the basis of/around the painful experiences are a valuable and viable addition in the examination of children’s development.

This study contributes to a broader literature of parent–child reminiscing about past painful events. It is the first study to demonstrate the association between reminiscing about past painful events and children’s broader cognitive functioning. This study extends recent research that has demonstrated an association between parental reminiscing and children’s pain-related cognitions (i.e., pain memory biases; Noel et al., 2019), in which mothers’ and fathers’ greater use of elaborations and emotional words was linked to children’s positively biased memories for postsurgical pain (i.e., recalling less pain than was initially reported). Although cross-sectional, these findings indicate that an elaborative parental reminiscing style may have beneficial effects on broader/overall cognitive development, above and beyond pain-specific memory biases. In line with socio-cultural theories of development (Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Vygotsky, 1980), these findings support the argument that socio-linguistic interactions such as reminiscing between parents and children influence the children’s development. It is possible that children’s foundational cognitive functions (i.e., EF and EM) underlie these pain memory biases. The accuracy of children’s memory has been shown to be affected by individual differences in children’s verbal intelligence, self-perception of competence, and temperament (Chae & Ceci, 2005). Children’s core cognitive abilities may represent another area of individual differences to potentially explain some of the variability in why some children display more positively biased memories (Noel et al., 2019). Language-based interactions surrounding painful experiences are beneficial, malleable, and have the potential to be taught to parents (Noel, 2016). For example, in the context of their children’s recent surgery, parents in an intervention group were trained to reminisce in more adaptive ways with their children using reminiscing strategies, which resulted in changes of children’s memory for pain (Pavlova et al., revised and resubmitted). Specifically, parents who were trained to elaborate on positive aspects of the painful experience, reframe their children’s exaggerated pain memories, praise children’s coping and bravery, and reduce the use of pain-related words, had children who reported more accurate/positive memories for pain 1 week after the intervention. Our findings provide evidence that these interactions may potentially influence cognitive functioning, which underscores the potential benefits of processing and talking about these frequently experienced painful events in elaborative ways.

Importantly, the two cognitive domains assessed represent abilities shown to be malleable and responsive to intervention in young children (Diamond et al., 2007; Sasser et al., 2017; Shing & Lindenberger, 2011; Zhang et al., 2019). In an intervention study of a Vygotskian-informed preschool curriculum, comprised of a number of EF enhancing activities (e.g., dramatic play, self-regulatory private speech, memory, and attention aids), preschool-aged children performed significantly better on EF (i.e., inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility) than those in the standard literacy-based curriculum (Diamond et al., 2007). A longitudinal study demonstrated that when 4-year-old children participated in an intervention (i.e., socio-emotional and language-literacy enhancements to usual curriculum) to target EF, children who initially had low EF trajectories displayed significant improvements in EF 5 years later, compared with the control group (Sasser et al., 2017). Shing and Lindenberger (2011) summarized the effects of training (i.e., a mnemonic memory strategy to retrieve words based on location) on EM and concluded that EM increases in middle childhood with training. Parent–child reminiscing about past painful events such as needles and injuries may serve as a powerful context to influence these foundational skills early in development.

This study should be interpreted in light of limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional; therefore, directionality of the relationship between parents’ reminiscing style and children’s cognitive skills cannot be inferred. This relationship may operate bidirectionally, or there may be evocative effects whereby children’s cognitive skill level may influence how parents reminisce. For example, children who remember more details about a past event and/or have better developed attention; therefore can better attend to conversations with their parents, which may prompt parents to ask more open-ended elaborative questions and offer more explanations for the past events. Alternatively, parental use of yes–no repetition questions may be an attention moderating strategy with children who have less developed attentional skills. These findings may reflect parents adapting their reminiscing style to meet their children’s cognitive needs. However, research has demonstrated a causal connection between elaborative parental reminiscing style and children’s development (Van Bergen et al., 2009). Specifically, children of parents who were trained to reminisce using elaborative elements recalled more information about past autobiographical events and showed a greater understanding of emotions, than those in the control group. Future longitudinal research should examine the directionality of the relationship between parental reminiscing and children’s broader cognitive outcomes. In addition, the sample was predominantly white and affluent. Given cross-cultural differences found in parent–child reminiscing (e.g., Euro-American mothers have been found to reminisce using language higher in explanatory and emotional content than Chinese mothers; Wang et al., 2010), this examination should occur in more representative, culturally diverse samples. It is also possible that the type of painful event discussed may influence the patterns of parent–child reminiscing, children’s cognitive skills, and the relationship between these factors, and is a potential direction for future research. Future research should also examine potential differences in mechanisms underlying the relation between parent–child reminiscing and children’s cognitive skills for painful events versus other types of negative emotional events.

In conclusion, this study examined the relationship between parent–child reminiscing about past painful events and children’s broader development. Children’s cognitive abilities (i.e., EF and EM) differed as a function of parent role and child sex. Less frequent parental use of yes–no repetition questions was significantly related to boys’ but not girls’ better performance on an EF task. Parents who reminisced using more elaborative elements (i.e., explanations) had children who displayed greater performance on a measure of EM. These findings underscore that parent–child reminiscing about past painful events is a viable, rich, and unharnessed context in which to examine young children’s cognitive abilities. Pain (e.g., needles, injuries) is ubiquitous in early childhood and serves as salient events that can be readily processed between parents and children through language-based interactions occurring whilst reminiscing. These interactions influence not only autobiographical memories of these events but also broader cognitive development during a formative period of development. Future longitudinal research is required to determine the directionality of the relationship between parent–child reminiscing and children’s developmental outcomes.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council awarded to MN. M.P. was supported by the Alberta Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Graduate Studentship. S.G. was supported by Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

IBM Corp. (