-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ashley M Butler, Marisa E Hilliard, Courtney Titus, Evadne Rodriguez, Iman Al-Gadi, Yasmin Cole-Lewis, Deborah Thompson, Barriers and Facilitators to Involvement in Children’s Diabetes Management Among Minority Parents, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 45, Issue 8, September 2020, Pages 946–956, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz103

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study aimed to describe parents’ perceptions of the factors that facilitate or are barriers to their involvement in children’s type 1 diabetes (T1D) management among African American and Latino parents.

African American and Latino parents (N = 28) of 5- to 9-year-old children with T1D completed audio-recorded, semi-structured interviews that were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis. Themes were identified that aligned with the theoretically-derived Capability–Opportunity–Motivation–Behavior (COM-B) framework.

Parents described Capability-based facilitators of parent involvement, including positive stress management, religious/spiritual coping, organizational/planning skills, and diabetes knowledge. Capability-based barriers included child and parent distress. Interpersonal relationships, degree of flexibility in work environments, and access to diabetes technologies were both Opportunity-based facilitators and barriers; and Opportunity-based barriers consisted of food insecurity/low financial resources. Parents’ desire for their child to have a “normal” life was described as both a Motivation-based facilitator and barrier.

African American and Latino families described helpful and unhelpful factors that spanned all aspects of the COM-B model. Reinforcing or targeting families’ unique psychological, interpersonal, and environmental strengths and challenges in multilevel interventions has potential to maximize parental involvement in children’s diabetes management.

Introduction

Family completion of daily care tasks is essential for effective management of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in children (Chiang et al., 2018). The burden of daily tasks on parents and children is well-recognized and contributes to psychosocial distress and family conflicts (Chiang, Kirkman, Laffel, Peters, & Type 1 Diabetes Sourcebook Authors, 2014). These family challenges are associated with poorer adherence and glycemic outcomes (Drotar et al., 2013; Rohan et al., 2015), which can lead to diabetes complications (Chiang et al., 2014, 2018). Adolescence is a vulnerable period for treatment adherence and glycemic control (Schwandt et al., 2017). Implementing family routines earlier, during the school-age period (5–9 years) is an important step to protect against sharp declines in health behaviors and outcomes in adolescence.

Parents’ collaborative involvement in T1D management in childhood is recommended to promote adherence and positive health outcomes (Chiang et al., 2018). Collaborative parent involvement includes hands-on assistance with diabetes management tasks and close monitoring of children’s diabetes management activities (Chiang et al., 2018). This approach also involves cooperation with children when solving diabetes-related problems (Miller & Jawad, 2019) and balancing parental limit setting, clear expectations, and strong emotional support for diabetes management (Young, Lord, Patel, Gruhn, & Jaser, 2014). Together, these strategies during childhood predict higher engagement in self-management and lower hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) during adolescence (Armstrong, Mackey, & Streisand, 2011). Research with subsets of the population with T1D who are vulnerable to disruptions in collaborative family involvement is necessary to design targeted interventions that reduce the risk for poor outcomes.

Although there has been substantially less research focused on African American and Latino families of children with T1D, these racial/ethnic minority groups have been found to have lower collaborative involvement in diabetes management (Ellis et al., 2008; Lord et al., 2015). African American and Latino children also have poorer T1D adherence (Auslander, Thompson, Dreitzer, White, & Santiago, 1997; Gallegos-Macias, Macias, Kaufman, Skipper, & Kalishman, 2003) and troubling disparities in health outcomes, including poorer glycemic control and other medical complications (Redondo et al., 2018; Willi et al., 2015). In analyses that control for socioeconomic status, differences in glycemic control between Latino and non-Latino white (NLW) youth are no longer significant, but differences between NLW youth and African Americans persist (Willi et al., 2015). Young African American and Latino children who are diagnosed at age 9 or below are at higher risk for more rapid declines in glycemic control (Kahkoska et al., 2018). Research on collaborative involvement among minority families of young children can help inform strategies to improve family diabetes management and address outcome disparities.

There have been mixed results about patterns of collaborative involvement among African American and Latino parents. It is important to note that most studies that examined racial/ethnic differences in parenting in T1D have combined African American and Latino families into one racial/ethnic group and have primarily included English speaking parents. One study reported lower supervision of T1D management among African American and Latino parents compared with NLW parents (Ellis et al., 2008), and another reported greater supervision among Latino parents (Gallegos-Macias et al., 2003). African American and Latino parents have demonstrated more overinvolved, intrusive behavior when discussing diabetes-related stressors (Lord et al., 2015). The general child development literature supports conclusions of lower collaborative involvement among African American and Latino families. For example, middle-class African American parents tend to encourage independent behavior during early adolescence by promoting greater personal responsibility in daily tasks (Smetana & Chuang, 2001). African American and Latino parents demonstrate greater limit setting and similar or lower levels of warmth compared with NLW parents (Chao & Kanatsu, 2008).

While several studies suggest lower collaborative involvement among African American and Latino parents, few have investigated contributors to parental involvement in diabetes management among these groups. Parental depressive symptoms limit parent involvement among African American families of children with T1D (Eckshtain, Ellis, Kolmodin, & Naar-King, 2010). Higher family levels of diabetes-related supportive behaviors are associated with greater parental involvement among Latino families (Hsin, La Greca, Valenzuela, Moine, & Delamater, 2010). A more comprehensive understanding of factors related to parental T1D management involvement among African American and Latino families of young school-aged children is needed. These data will inform approaches that can promote treatment adherence and improve glycemic control in these groups. Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify facilitators and barriers to parental involvement in diabetes management using structured interviews with African American and Latino parents of children (5–9 years) with T1D.

Methods

Procedure and Participants

Parents were invited to participate in individual, semi-structured qualitative interviews at their child’s regularly scheduled diabetes clinic visit at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, TX, United States. Research staff screened the electronic medical record clinic schedule of upcoming appointments to identify potentially eligible families. Parents were eligible if they self-identified as either Latino/Hispanic or African American/Black, were fluent in English, were the primary caregiver of a child ages 5–9 with T1D, and their child had been diagnosed with T1D for more than 1 year. Parents who met the inclusion criteria were mailed a letter describing the study prior to their appointment and contacted via phone to determine interest in learning more about the study. Parents were informed that the purpose of the study was to identify facilitators and barriers to parental involvement in diabetes management among African American and Latino parents. If the parent indicated interest, study staff met with them for 15–20 minutes before the appointment to confirm eligibility and complete written informed consent. Study staff then completed audio-recorded interviews in-person after clinic appointments or via telephone. Participants were compensated $25. The Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Forty eligible parents were approached in the clinic and invited to participate in the study. One parent declined to participate due to not having time to complete procedures. Four parents requested to be approached at a later clinic visit or needed more time to think about participation. Saturation was attained before we were able to reapproach parents. Initially, 35 of the eligible families (87%) consented and completed the background questionnaires. Seven of the consented parents requested to complete it via phone but were not able to be reached. The final sample (N = 28; 70% of eligible parents) who completed a semi-structured interview were 50% (N = 14) non-Hispanic African American/Black participants and 50% (N = 14) Latino/Hispanic parents. The demographic characteristics of parents who completed the interview did not differ from those who consented but were not reached by phone.

Data Collection

Parents completed a demographic questionnaire that contained items with categorical response scales assessing their marital status, age, education, and yearly household income. Research staff also obtained children’s diabetes duration and most recent HbA1c from the electronic medical record. Trained research staff conducted individual semi-structured interviews with parents in person or by telephone. The goal of the interviews was to learn about participant’s daily experiences with managing T1D, and specifically, barriers and facilitators to parental involvement in management.

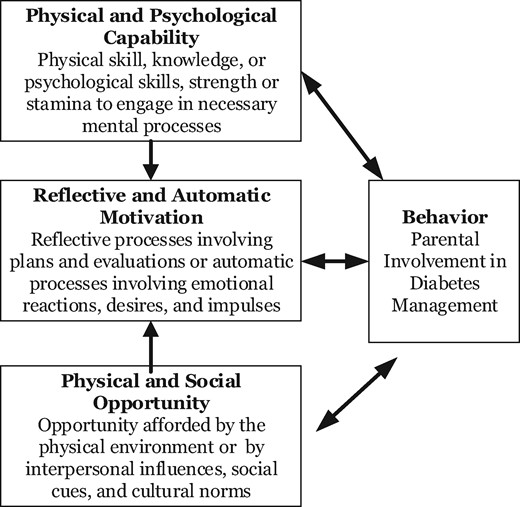

The senior researchers created interview questions informed by the Capability–Opportunity–Motivation–Behavior (COM-B) model (Michie, van Stralen, & West, 2011), a theoretically-based framework that was developed from a synthesis of 19 frameworks to generate an inclusive set of theoretical constructs associated with successful behavior change (Michie et al., 2011). The COM-B model organizes constructs into capability, opportunity, and motivation-related factors (Figure 1). The model was selected because it includes an emphasis on the environmental context in which behavior occurs. Aligned with the model, interview questions focused on factors that influence parental involvement in their child’s diabetes management at home and at work, perceived strengths and challenges related to their involvement, and reasons for their level of involvement in diabetes tasks (Table I). Interviewers were trained to follow the script and use open-ended, non-leading questions to elicit participant discussion of the topics. Probes were used as needed to expand, clarify, and understand responses. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription company with specialized expertise in health-related transcription. The average length of interviews was 39 minutes.

Capability–Opportunity–Motivation–Behavior (COM-B) model.

Note. Adapted from Michie, Atkins, and West (2014).

| COM-B construct . | Questions and prompts . |

|---|---|

| Capability |

|

| Opportunity |

|

| Motivation |

|

| COM-B construct . | Questions and prompts . |

|---|---|

| Capability |

|

| Opportunity |

|

| Motivation |

|

| COM-B construct . | Questions and prompts . |

|---|---|

| Capability |

|

| Opportunity |

|

| Motivation |

|

| COM-B construct . | Questions and prompts . |

|---|---|

| Capability |

|

| Opportunity |

|

| Motivation |

|

Data Analysis

Research staff checked the interview transcripts for accuracy against the audio prior to analysis. They, then, analyzed the data following three steps: initial reading of transcripts, coding, and categorization. The senior researchers reviewed 20% of the transcripts to create an initial set of codes using thematic analysis. Researchers used a hybrid analytic approach that combined inductive and deductive reasoning, and followed procedures for qualitative analysis outlined by (Braun and Clarke, 2006) and Wu, Thompson, Aroian, McQuaid, and Deatrick (2016). The initial codebook was based on the investigation of a priori codes representing common concepts in the literature for this population (i.e., family support, parental distress) as well as on emergent codes representing important ideas or concepts not captured by the a priori codes (e.g., employment schedule). The codes were grouped into two categories to facilitate coding: barriers to or facilitators of parental involvement in T1D management tasks. Codes and definitions were recorded in a codebook to help ensure the consistent application of the codes throughout the coding process. Three research coordinators trained in qualitative analysis coded the remaining transcripts using the codebook. Each transcript was coded by two coordinators. The three coordinators held meetings to review codes, generate new emergent codes, and resolve any discrepant coding. Disagreements were settled by the third reviewer or taken before the senior researchers for review; ultimately at least two-thirds reviewers agreed on all codes for every transcript. NVivo (11) was used to facilitate coding and analysis. During the analysis, the number of times a code appeared, along with the race/ethnicity of the parent assigned that code, was captured. Saturation for each racial/ethnic group was monitored by coordinators continuously during analysis and was achieved for each group before all transcripts were coded for each group. However, all transcripts were coded for the analysis.

Finally, the coded data were analyzed by the two senior investigators to identify barriers and facilitators to diabetes management. Senior investigators independently organized the codes by relevance to themes aligned with the COM-B model, and meetings were held to discuss and come to consensus regarding themes and their alignment with constructs in the COM-B model. To explore possible similarities and differences between African American and Latino participants, the senior investigators also held meetings to jointly examine the data for patterns of certain codes appearing more or less frequently, or not at all, for either group. Specifically, the number of times a code appeared within each racial/ethnic group was reviewed.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table II summarizes the sample’s demographic characteristics of the study sample. Most participants were mothers, had an undergraduate/graduate degree, and reported a yearly household income of $60,000 or less. Slightly more than half were married. Their children had an average age of 7.4 years and average T1D duration of 3.6 years. Consistent with national trends for African American and Latino children in this age range (Foster et al., 2019) average HbA1c was 8.8%. There were no significant racial/ethnic differences in demographics.

| Characteristic . | Hispanic/Latino (n = 14) . | Non-Hispanic AA/Black (n = 14) . | Total (N = 28) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents (n or %) | |||

| Gender completing interview | |||

| Female | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Female and male dyad | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married/divorced/separated | 43% | 43% | 43% |

| Married | 57% | 57% | 57% |

| Primary caregiver age (years) | |||

| ≤35 | 57% | 36% | 46% |

| ≥36 | 43% | 64% | 54% |

| Primary caregiver highest education | |||

| High school | 36% | 29% | 32% |

| Trade/technical degree | 29% | 21% | 25% |

| Undergraduate/graduate degree | 36% | 50% | 43% |

| Yearly household income | |||

| Below $60,000 | 71% | 50% | 61% |

| $60,000 or above | 29% | 50% | 39% |

| Children (% or M and SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.5 |

| Female | 50% | 50% | 50% |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.7 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 8.8 ± 1.1 |

| Characteristic . | Hispanic/Latino (n = 14) . | Non-Hispanic AA/Black (n = 14) . | Total (N = 28) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents (n or %) | |||

| Gender completing interview | |||

| Female | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Female and male dyad | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married/divorced/separated | 43% | 43% | 43% |

| Married | 57% | 57% | 57% |

| Primary caregiver age (years) | |||

| ≤35 | 57% | 36% | 46% |

| ≥36 | 43% | 64% | 54% |

| Primary caregiver highest education | |||

| High school | 36% | 29% | 32% |

| Trade/technical degree | 29% | 21% | 25% |

| Undergraduate/graduate degree | 36% | 50% | 43% |

| Yearly household income | |||

| Below $60,000 | 71% | 50% | 61% |

| $60,000 or above | 29% | 50% | 39% |

| Children (% or M and SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.5 |

| Female | 50% | 50% | 50% |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.7 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 8.8 ± 1.1 |

| Characteristic . | Hispanic/Latino (n = 14) . | Non-Hispanic AA/Black (n = 14) . | Total (N = 28) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents (n or %) | |||

| Gender completing interview | |||

| Female | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Female and male dyad | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married/divorced/separated | 43% | 43% | 43% |

| Married | 57% | 57% | 57% |

| Primary caregiver age (years) | |||

| ≤35 | 57% | 36% | 46% |

| ≥36 | 43% | 64% | 54% |

| Primary caregiver highest education | |||

| High school | 36% | 29% | 32% |

| Trade/technical degree | 29% | 21% | 25% |

| Undergraduate/graduate degree | 36% | 50% | 43% |

| Yearly household income | |||

| Below $60,000 | 71% | 50% | 61% |

| $60,000 or above | 29% | 50% | 39% |

| Children (% or M and SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.5 |

| Female | 50% | 50% | 50% |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.7 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 8.8 ± 1.1 |

| Characteristic . | Hispanic/Latino (n = 14) . | Non-Hispanic AA/Black (n = 14) . | Total (N = 28) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents (n or %) | |||

| Gender completing interview | |||

| Female | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Female and male dyad | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married/divorced/separated | 43% | 43% | 43% |

| Married | 57% | 57% | 57% |

| Primary caregiver age (years) | |||

| ≤35 | 57% | 36% | 46% |

| ≥36 | 43% | 64% | 54% |

| Primary caregiver highest education | |||

| High school | 36% | 29% | 32% |

| Trade/technical degree | 29% | 21% | 25% |

| Undergraduate/graduate degree | 36% | 50% | 43% |

| Yearly household income | |||

| Below $60,000 | 71% | 50% | 61% |

| $60,000 or above | 29% | 50% | 39% |

| Children (% or M and SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.5 |

| Female | 50% | 50% | 50% |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.7 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 8.8 ± 1.1 |

Qualitative Themes

Themes are organized below by their alignment with the COM-B model, and by whether the theme was a barrier, facilitator, or both a facilitator and barrier. Table III illustrates each theme with example excerpts from participants, noted by the family race/ethnicity and child age.

| COM-B domain . | Theme . | Barrier . | Facilitator . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Parental distress | I definitely hit a point where I was depressed because I just felt like the diabetes was running my life. At some point, you have to snatch your life back…. It’s helped a lot. It definitely gives me energy. I went from fixing dinner to making dinner from scratch now. I monitor everything that we put in our bodies (AA mother, 5-year-old son) | ||

| Stigma | …after school things or at sports, it’s a little hard to get onto the field or onto the court and try to treat a low in front of a lotta people. There’s just a lot of wandering eyes, asking questions. Little kids don’t know. I think that’s pretty hard. (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Diabetes knowledge | Everybody that was going to be alone with her at some point, was trained and informed by us and the nurse there to where they felt comfortable to either call us or call the nurse if there was a situation that they were questioning or whatever, so we didn’t have to worry about that (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Stress management | Because I was lookin’ for something, and so once I saw the [online community for parents of children with T1D] … you just talk about your experiences. I found it on Facebook cuz I needed something to not be so depressed about it (AA mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Religious/spiritual coping | So, he has a relationship with God himself. So, we have our prayers and stuff. We pray together at night and that kinda thing. So, that really, really, really helps a lot” (AA mother, 6-year-old son). We go to church a lot. That helps us out too, just believing that everything's going to go okay and we don’t—we're not given challenges that we're not going to overcome” (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Organization skills | … just trying be organized and always keeping everything. You’re planning everything. (L mother, 8-year-old son) | |||

| Opportunity | Interpersonal relationships | I mean the challenge is his dad and I communicating. We’re just about things when things are going up or down. It’s hard to look at weekly blood sugar levels like we’re supposed to because there’s so much communication that has to be done… (L mother, 8-year-old son) | If it’s to where I feel like I just can’t do it myself, I’ll call the on call doctor and talk with them. They are really good about telling me what I need to do and following up on it. They help me out if she gets too high to where I’m scared that she’s going go into DKA or something like that, they’ll help me get through that. … (L mother, 9-year-old daughter) | |

| That also leaves the brunt of the work on me, because he’s [spouse] not there that much. …. struggle is that, sometimes it gets tough having to do it every single day… That was a big struggle for us and it made it harder on our marriage (L mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||||

| Work environment | I cannot have my phone on me. That’s probably the difficult part. I cannot have my phone on me, so they (the school) have to know to call my work (L mother, 6-year-old daughter) | Both companies, both managers my boss and her boss, they’re really understanding. They don’t give us any issues when something comes up… We don’t get reprimanded: “Oh, you’re takin’ too much time off for your son,” because my son is my life… They’re very good about understanding that. We’re probably one of the lucky ones (AA father, 9-year-old son) | ||

| Access to technology | He needs the pump you know and it’s … more than a convenience thing … It helps me manage it better (AA mother, 6-year-old son)Well, with this new technology, I can … monitor [child]’s sugar glucose from work, so that helped me a lot (L father, 9-year-old daughter) | She's on Medicaid, so the Dexcom comes out of pocket for us. When we don't have that, her life is dramatically different. She doesn’t feel safe, so she will often go to the nurse's office every hour or two, just because she really does not have the safety net of the Dexcom when we can't afford to have the supplies. That's probably our biggest issue because, at least when we are seeing the fluctuations in blood sugars with the Dexcom, we can do something about it. When we don’t have the Dexcom, the nurses just have to kind of rely on her (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||

| Financial resources | It’s sometimes not always havin’ enough to keep around the house to help manage for those highs and lows, is the biggest one (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Motivation | Normalcy | It’s hard to tell her no. We have a 2-year-old, so if he’s eatin’ she wants to eat too. You don’t wanna single her out or tell her she can’t have somethin’. Or he’s eatin’ candy or fruit snacks and we don’t have anything that’s sugarfree that she wants. It’s hard to just tell her no and not keep her from having as much insulin throughout the day (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | You worry about everything else. We’ll worry about diabetes.’ We try to keep that pressure off of him. We deal with the medicine and all that other stuff. We try to allow him to be a little boy (AA father, 9-year-old son) | |

| Prioritizing their child | At the end of the day, regardless how bad it is, I have to do it. It's her health. (AA father, 5-year-old daughter) | |||

| And definitely everything I do revolves on him. I work nights. I’m available for him during the daytime always, especially when he’s away from me at school (AA mother, 7-year-old son) |

| COM-B domain . | Theme . | Barrier . | Facilitator . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Parental distress | I definitely hit a point where I was depressed because I just felt like the diabetes was running my life. At some point, you have to snatch your life back…. It’s helped a lot. It definitely gives me energy. I went from fixing dinner to making dinner from scratch now. I monitor everything that we put in our bodies (AA mother, 5-year-old son) | ||

| Stigma | …after school things or at sports, it’s a little hard to get onto the field or onto the court and try to treat a low in front of a lotta people. There’s just a lot of wandering eyes, asking questions. Little kids don’t know. I think that’s pretty hard. (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Diabetes knowledge | Everybody that was going to be alone with her at some point, was trained and informed by us and the nurse there to where they felt comfortable to either call us or call the nurse if there was a situation that they were questioning or whatever, so we didn’t have to worry about that (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Stress management | Because I was lookin’ for something, and so once I saw the [online community for parents of children with T1D] … you just talk about your experiences. I found it on Facebook cuz I needed something to not be so depressed about it (AA mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Religious/spiritual coping | So, he has a relationship with God himself. So, we have our prayers and stuff. We pray together at night and that kinda thing. So, that really, really, really helps a lot” (AA mother, 6-year-old son). We go to church a lot. That helps us out too, just believing that everything's going to go okay and we don’t—we're not given challenges that we're not going to overcome” (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Organization skills | … just trying be organized and always keeping everything. You’re planning everything. (L mother, 8-year-old son) | |||

| Opportunity | Interpersonal relationships | I mean the challenge is his dad and I communicating. We’re just about things when things are going up or down. It’s hard to look at weekly blood sugar levels like we’re supposed to because there’s so much communication that has to be done… (L mother, 8-year-old son) | If it’s to where I feel like I just can’t do it myself, I’ll call the on call doctor and talk with them. They are really good about telling me what I need to do and following up on it. They help me out if she gets too high to where I’m scared that she’s going go into DKA or something like that, they’ll help me get through that. … (L mother, 9-year-old daughter) | |

| That also leaves the brunt of the work on me, because he’s [spouse] not there that much. …. struggle is that, sometimes it gets tough having to do it every single day… That was a big struggle for us and it made it harder on our marriage (L mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||||

| Work environment | I cannot have my phone on me. That’s probably the difficult part. I cannot have my phone on me, so they (the school) have to know to call my work (L mother, 6-year-old daughter) | Both companies, both managers my boss and her boss, they’re really understanding. They don’t give us any issues when something comes up… We don’t get reprimanded: “Oh, you’re takin’ too much time off for your son,” because my son is my life… They’re very good about understanding that. We’re probably one of the lucky ones (AA father, 9-year-old son) | ||

| Access to technology | He needs the pump you know and it’s … more than a convenience thing … It helps me manage it better (AA mother, 6-year-old son)Well, with this new technology, I can … monitor [child]’s sugar glucose from work, so that helped me a lot (L father, 9-year-old daughter) | She's on Medicaid, so the Dexcom comes out of pocket for us. When we don't have that, her life is dramatically different. She doesn’t feel safe, so she will often go to the nurse's office every hour or two, just because she really does not have the safety net of the Dexcom when we can't afford to have the supplies. That's probably our biggest issue because, at least when we are seeing the fluctuations in blood sugars with the Dexcom, we can do something about it. When we don’t have the Dexcom, the nurses just have to kind of rely on her (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||

| Financial resources | It’s sometimes not always havin’ enough to keep around the house to help manage for those highs and lows, is the biggest one (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Motivation | Normalcy | It’s hard to tell her no. We have a 2-year-old, so if he’s eatin’ she wants to eat too. You don’t wanna single her out or tell her she can’t have somethin’. Or he’s eatin’ candy or fruit snacks and we don’t have anything that’s sugarfree that she wants. It’s hard to just tell her no and not keep her from having as much insulin throughout the day (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | You worry about everything else. We’ll worry about diabetes.’ We try to keep that pressure off of him. We deal with the medicine and all that other stuff. We try to allow him to be a little boy (AA father, 9-year-old son) | |

| Prioritizing their child | At the end of the day, regardless how bad it is, I have to do it. It's her health. (AA father, 5-year-old daughter) | |||

| And definitely everything I do revolves on him. I work nights. I’m available for him during the daytime always, especially when he’s away from me at school (AA mother, 7-year-old son) |

| COM-B domain . | Theme . | Barrier . | Facilitator . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Parental distress | I definitely hit a point where I was depressed because I just felt like the diabetes was running my life. At some point, you have to snatch your life back…. It’s helped a lot. It definitely gives me energy. I went from fixing dinner to making dinner from scratch now. I monitor everything that we put in our bodies (AA mother, 5-year-old son) | ||

| Stigma | …after school things or at sports, it’s a little hard to get onto the field or onto the court and try to treat a low in front of a lotta people. There’s just a lot of wandering eyes, asking questions. Little kids don’t know. I think that’s pretty hard. (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Diabetes knowledge | Everybody that was going to be alone with her at some point, was trained and informed by us and the nurse there to where they felt comfortable to either call us or call the nurse if there was a situation that they were questioning or whatever, so we didn’t have to worry about that (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Stress management | Because I was lookin’ for something, and so once I saw the [online community for parents of children with T1D] … you just talk about your experiences. I found it on Facebook cuz I needed something to not be so depressed about it (AA mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Religious/spiritual coping | So, he has a relationship with God himself. So, we have our prayers and stuff. We pray together at night and that kinda thing. So, that really, really, really helps a lot” (AA mother, 6-year-old son). We go to church a lot. That helps us out too, just believing that everything's going to go okay and we don’t—we're not given challenges that we're not going to overcome” (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Organization skills | … just trying be organized and always keeping everything. You’re planning everything. (L mother, 8-year-old son) | |||

| Opportunity | Interpersonal relationships | I mean the challenge is his dad and I communicating. We’re just about things when things are going up or down. It’s hard to look at weekly blood sugar levels like we’re supposed to because there’s so much communication that has to be done… (L mother, 8-year-old son) | If it’s to where I feel like I just can’t do it myself, I’ll call the on call doctor and talk with them. They are really good about telling me what I need to do and following up on it. They help me out if she gets too high to where I’m scared that she’s going go into DKA or something like that, they’ll help me get through that. … (L mother, 9-year-old daughter) | |

| That also leaves the brunt of the work on me, because he’s [spouse] not there that much. …. struggle is that, sometimes it gets tough having to do it every single day… That was a big struggle for us and it made it harder on our marriage (L mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||||

| Work environment | I cannot have my phone on me. That’s probably the difficult part. I cannot have my phone on me, so they (the school) have to know to call my work (L mother, 6-year-old daughter) | Both companies, both managers my boss and her boss, they’re really understanding. They don’t give us any issues when something comes up… We don’t get reprimanded: “Oh, you’re takin’ too much time off for your son,” because my son is my life… They’re very good about understanding that. We’re probably one of the lucky ones (AA father, 9-year-old son) | ||

| Access to technology | He needs the pump you know and it’s … more than a convenience thing … It helps me manage it better (AA mother, 6-year-old son)Well, with this new technology, I can … monitor [child]’s sugar glucose from work, so that helped me a lot (L father, 9-year-old daughter) | She's on Medicaid, so the Dexcom comes out of pocket for us. When we don't have that, her life is dramatically different. She doesn’t feel safe, so she will often go to the nurse's office every hour or two, just because she really does not have the safety net of the Dexcom when we can't afford to have the supplies. That's probably our biggest issue because, at least when we are seeing the fluctuations in blood sugars with the Dexcom, we can do something about it. When we don’t have the Dexcom, the nurses just have to kind of rely on her (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||

| Financial resources | It’s sometimes not always havin’ enough to keep around the house to help manage for those highs and lows, is the biggest one (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Motivation | Normalcy | It’s hard to tell her no. We have a 2-year-old, so if he’s eatin’ she wants to eat too. You don’t wanna single her out or tell her she can’t have somethin’. Or he’s eatin’ candy or fruit snacks and we don’t have anything that’s sugarfree that she wants. It’s hard to just tell her no and not keep her from having as much insulin throughout the day (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | You worry about everything else. We’ll worry about diabetes.’ We try to keep that pressure off of him. We deal with the medicine and all that other stuff. We try to allow him to be a little boy (AA father, 9-year-old son) | |

| Prioritizing their child | At the end of the day, regardless how bad it is, I have to do it. It's her health. (AA father, 5-year-old daughter) | |||

| And definitely everything I do revolves on him. I work nights. I’m available for him during the daytime always, especially when he’s away from me at school (AA mother, 7-year-old son) |

| COM-B domain . | Theme . | Barrier . | Facilitator . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Parental distress | I definitely hit a point where I was depressed because I just felt like the diabetes was running my life. At some point, you have to snatch your life back…. It’s helped a lot. It definitely gives me energy. I went from fixing dinner to making dinner from scratch now. I monitor everything that we put in our bodies (AA mother, 5-year-old son) | ||

| Stigma | …after school things or at sports, it’s a little hard to get onto the field or onto the court and try to treat a low in front of a lotta people. There’s just a lot of wandering eyes, asking questions. Little kids don’t know. I think that’s pretty hard. (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Diabetes knowledge | Everybody that was going to be alone with her at some point, was trained and informed by us and the nurse there to where they felt comfortable to either call us or call the nurse if there was a situation that they were questioning or whatever, so we didn’t have to worry about that (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Stress management | Because I was lookin’ for something, and so once I saw the [online community for parents of children with T1D] … you just talk about your experiences. I found it on Facebook cuz I needed something to not be so depressed about it (AA mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Religious/spiritual coping | So, he has a relationship with God himself. So, we have our prayers and stuff. We pray together at night and that kinda thing. So, that really, really, really helps a lot” (AA mother, 6-year-old son). We go to church a lot. That helps us out too, just believing that everything's going to go okay and we don’t—we're not given challenges that we're not going to overcome” (L mother, 9-year-old son) | |||

| Organization skills | … just trying be organized and always keeping everything. You’re planning everything. (L mother, 8-year-old son) | |||

| Opportunity | Interpersonal relationships | I mean the challenge is his dad and I communicating. We’re just about things when things are going up or down. It’s hard to look at weekly blood sugar levels like we’re supposed to because there’s so much communication that has to be done… (L mother, 8-year-old son) | If it’s to where I feel like I just can’t do it myself, I’ll call the on call doctor and talk with them. They are really good about telling me what I need to do and following up on it. They help me out if she gets too high to where I’m scared that she’s going go into DKA or something like that, they’ll help me get through that. … (L mother, 9-year-old daughter) | |

| That also leaves the brunt of the work on me, because he’s [spouse] not there that much. …. struggle is that, sometimes it gets tough having to do it every single day… That was a big struggle for us and it made it harder on our marriage (L mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||||

| Work environment | I cannot have my phone on me. That’s probably the difficult part. I cannot have my phone on me, so they (the school) have to know to call my work (L mother, 6-year-old daughter) | Both companies, both managers my boss and her boss, they’re really understanding. They don’t give us any issues when something comes up… We don’t get reprimanded: “Oh, you’re takin’ too much time off for your son,” because my son is my life… They’re very good about understanding that. We’re probably one of the lucky ones (AA father, 9-year-old son) | ||

| Access to technology | He needs the pump you know and it’s … more than a convenience thing … It helps me manage it better (AA mother, 6-year-old son)Well, with this new technology, I can … monitor [child]’s sugar glucose from work, so that helped me a lot (L father, 9-year-old daughter) | She's on Medicaid, so the Dexcom comes out of pocket for us. When we don't have that, her life is dramatically different. She doesn’t feel safe, so she will often go to the nurse's office every hour or two, just because she really does not have the safety net of the Dexcom when we can't afford to have the supplies. That's probably our biggest issue because, at least when we are seeing the fluctuations in blood sugars with the Dexcom, we can do something about it. When we don’t have the Dexcom, the nurses just have to kind of rely on her (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | ||

| Financial resources | It’s sometimes not always havin’ enough to keep around the house to help manage for those highs and lows, is the biggest one (AA mother, 8-year-old daughter) | |||

| Motivation | Normalcy | It’s hard to tell her no. We have a 2-year-old, so if he’s eatin’ she wants to eat too. You don’t wanna single her out or tell her she can’t have somethin’. Or he’s eatin’ candy or fruit snacks and we don’t have anything that’s sugarfree that she wants. It’s hard to just tell her no and not keep her from having as much insulin throughout the day (AA mother, 7-year-old daughter) | You worry about everything else. We’ll worry about diabetes.’ We try to keep that pressure off of him. We deal with the medicine and all that other stuff. We try to allow him to be a little boy (AA father, 9-year-old son) | |

| Prioritizing their child | At the end of the day, regardless how bad it is, I have to do it. It's her health. (AA father, 5-year-old daughter) | |||

| And definitely everything I do revolves on him. I work nights. I’m available for him during the daytime always, especially when he’s away from me at school (AA mother, 7-year-old son) |

Psychological Capability—Barriers

Parental Distress

Many parents discussed how their own distress made it difficult to provide hands-on assistance and set limits and clear expectations. Many discussed their own diabetes burnout as well as difficulty coping with their child’s negative emotions and burnout.

Psychological Capability—Facilitators

Strong Diabetes Knowledge and Teaching Other Caregivers

Parents emphasized that having adequate knowledge about diabetes and its treatment enhanced their ability to be involved and to teach other individuals who provide care for their child. Effective knowledge and teaching facilitated communication with other caregivers, and thereby, improved parental monitoring of the child’s diabetes-related activities when the parent was not present (e.g., knowing what the child ate or whether blood glucose checks were completed).

Stress Management Skills and Positive Coping

Parents indicated that management of stress, both related to their child’s diabetes as well as stress from other sources allowed them to effectively engage in their child’s management. Parents described their stress management strategies including seeking support from online sources, sending their child to diabetes camps, and exercise. Several parents described using spirituality or religion to cope with their negative emotions, which enabled them to maintain involvement in their child’s diabetes care. Parents also indicated encouraging similar coping strategies in their children.

Strong Organization and Planning Skills

A substantial proportion of interviewed parents described their organizational and planning skills facilitated strong involvement in diabetes management. As examples, parents described planning meals and snacks, implementing diabetes management tools, ensuring cues in the environment as reminders for diabetes tasks, and ensuring consistent daily routines and schedules for their child.

Social and Physical Environment Opportunity—Both Barriers and Facilitators

Interpersonal Relationships

Several themes related to interpersonal and social influences emerged representing challenges and facilitators of involvement in diabetes management. Parents described that the quality, collaboration, and degree of support from and communication with family (spouse, nuclear family, and extended family), school/childcare staff, and health care providers could either enhance or limit their involvement. First, many parents emphasized the role of extended family or spouses/significant others. Several parents indicated that family members’ fear or low knowledge about T1D resulted in limited hands-on support with diabetes management tasks. Parents noted that family member’s unsupportiveness contributed to their own distress, which in turn limited their ability to be adequately involved in diabetes management. Second, many parents described childcare/school staff discomfort or unwillingness to engage in diabetes care and had difficulty identifying childcare, which contributed to increased distress and burnout, which in turn lowered involvement. However, other parents described strong relationships with childcare providers, including frequent communication and engagement in problem-solving with the family. This allowed parents to effectively monitor diabetes tasks. Finally, several parents also talked about the quality of communication or relationships with their diabetes health care providers either increased or decreased distress, and thereby, facilitated or served as a challenge, respectively.

Flexibility or Rigidity in the Work Environment

Parents indicated that time constraints or rigidity in the work environment were challenges to monitoring and providing hand-on assistance with diabetes tasks (e.g., leaving work to assist while child is at school). Other parents noted that flexibility in their work environment facilitated their involvement.

Access to Technology

Several parents described how diabetes devices facilitated close monitoring and ability to provide hands-on assistance. Other parents noted that lack of or limited access to diabetes technologies is a barrier.

Social and Physical Environment Opportunity—Barrier

Limited financial resources

Several parents described food insecurity and limited financial resources limits their level of assistance with diabetes management, such as deciding what should be eaten to effectively manage blood glucose levels.

Automatic Motivation—Barrier

Perceived Stigma

Several parents indicated their own or their child’s feelings of shame related to having diabetes are barriers to limit setting (e.g., not allowing certain snacks) and providing hands-on assistance with management tasks in public.

Reflective Motivation—Barrier and Facilitator

Normalcy

Some parents indicated that their desire for their child to have a “normal life” is a barrier to limit setting and setting clear expectations. Conversely, several parents described this desire as a motivation that facilitated their engagement in hands-on assistance, providing emotional support, and cooperative problem-solving. Parents noted that by minimizing T1D-related activities for their child, their child could engage in activities with peers without burden.

Reflective Motivation—Facilitator

Prioritizing Their Child

Parents described that emphasizing their child’s needs over other responsibilities helped them to remain highly involved in their child’s T1D management.

Racial/Ethnic Differences

Examination of codes across racial/ethnic groups revealed that codes were similar for both racial/ethnic groups with the exception of one finding. While both African American and Latino parents identified the roles of support and communication with family in general, African American parents tended to emphasize extended family members (e.g., child’s grandparents, aunts/uncles) while Latino parents tended to emphasize significant others (e.g., spouse).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to identify barriers and facilitators to parent involvement in diabetes tasks among African American and Latino families. Notable findings of this research included that diverse psychological, interpersonal, environmental, and motivational factors contribute to parental involvement in diabetes tasks, and several types of contributors were both facilitators and barriers (e.g., work environment). These diverse factors bolster the importance of multidisciplinary teams that can address the psychological and mental health needs of parents, encourage culturally appropriate coping strategies, support access to social resources, and advocate for supportive school and work environments for socioeconomically diverse African American and Latino families of children with T1D. In addition, there were few racial/ethnic differences in perceived barriers or facilitators, which suggest many similarities among African American and Latino parents of young children.

Few studies have focused on factors that contribute to parental involvement in diabetes management among samples of primarily racial/ethnic minority groups who have disparities in diabetes outcomes. Among these studies, two targeted primarily African American families (Carcone, Ellis, & Naar-King, 2012; Eckshtain et al., 2010), and one focused on Latino families (Hsin et al., 2010). Both studies examined a relatively limited number of factors that may influence parental involvement. The findings reported here are the first to identify an inclusive set of factors that influence parental involvement using rigorous qualitative methods and a comprehensive theoretically-based framework (i.e., the COM-B model).

Psychological Capabilities

The current study findings indicating that low psychological capabilities (i.e., mental health symptoms, distress) serve as important barriers to parental involvement align with previous studies conducted with minority parents of children with diabetes. Findings from the National Survey of Children’s Health showed that African American and Latino mothers of children with T1D experience poorer psychological well-being than NLW mothers (Streisand, Mackey, & Herge, 2010). This has implications for children’s health, as studies with African American families have reported associations between parental psychological symptoms and poor diabetes outcomes. For example, parental depressive symptoms in African Americans have been associated with lower levels of warmth, monitoring, and involvement in diabetes management, which in turn were associated with poorer glycemic control in adolescents (Eckshtain et al., 2010). Among African American families from single-parent and low-income households, parental depressive and anxiety symptoms contributed to poorer glycemic control by reducing diabetes management behaviors, including blood glucose monitoring (Carcone et al., 2012). Carcone et al. (2012) concluded that parental distress that occurs when single parents are primarily responsible for their children’s diabetes care tasks might lead them to transfer care tasks to children before children are fully ready and capable of accepting responsibility for their care. Our findings emphasize the role of parental psychological functioning in parental involvement, including the barrier posed by emotional distress and the benefits that effective stress management and organizational strategies can offer. These themes are in accord with clinical recommendations to use screening tools to identify parents with increased stress or mental health symptoms, deliver psychoeducation and skills training, provide referrals to mental health care, and encourage parents to actively seek support (Whittemore, Jaser, Chao, Jang, & Grey, 2012).

An important finding was that the African American and Latino parents in this sample commonly used religious coping and spirituality to manage stress related to children’s diabetes. Similarly, Lipman et al. (2012) reported that compared with NLW parents, African American parents of children with T1D rate faith as more important in living well with T1D. These findings echo national studies of families without diabetes, which have shown greater religious participation and spirituality among African Americans and Latinos compared with NLWs (Chatters, Taylor, Bullard, & Jackson, 2009; Fitchett et al., 2007). Religious/spiritual coping has also been found among African American and Latino parents of children with sickle cell disease and asthma (Cotton et al., 2009; Desai, Rivera, & Backes, 2016). The use of spiritual/religious coping as a resource among parents to buffer stress and facilitate their involvement in T1D management has several implications for clinical practice with socioeconomically diverse African American and Latino families. The findings underscore assessing spiritual and religious beliefs in the clinical setting, referring parents to spiritually-integrated mental health services, and exploring ways parents can seek further support (e.g., support from family, friends, or religious institutions) to strengthen religious/spiritual coping resources.

In addition to strategies to cope with stressors, other facilitators of parental involvement included having high levels of knowledge about diabetes and using effective strategies for organization and time management. Parents’ knowledge about diabetes has been linked with linked with glycemic outcomes in children under age 9 (Stallwood, 2006). This study is consistent with our findings that parents perceive comprehensive diabetes knowledge helps them be more involved in their children’s diabetes management. These themes highlight the importance of multidisciplinary care and support for families of children with T1D—in addition to medical and mental health support, diabetes educators, social workers, and nurses, offer skills training and education that can help parents maximize involvement.

Social and Physical Opportunities

The current study findings regarding family and other relationships align with previous research. Among Latino families of children with T1D, higher satisfaction with family support perceived by youth has been related to higher levels of parental sharing of diabetes responsibilities (Hsin et al., 2010). The current study extends these previous findings on nuclear family support to also include social support provided by extended family members, childcare/school staff, and health care providers. Similar to our finding that African American parents tended to emphasize the value of support from extended family members, Lipman et al. (2012) reported African American parents of youth with T1D showed higher levels of importance ascribed to extended family. In contrast, our study is the first to suggest Latino families may emphasize the value of spousal support. Neither group devalued support from any family members (nuclear, marital, or extended), but rather these were slight differences in emphasis. In addition, our results are in line with previous research reporting African American parents particularly value school support and having positive interactions in the health care environment compared with non-Hispanic white parents (Lipman et al., 2012).

Our findings also indicated that aspects of the physical environment can present roadblocks for African American and Latino families’ involvement. Poor access to diabetes technologies, employment-related time limitations and restrictive policies (e.g., inability to carry a cell phone), and food insecurity interfered with parents’ ability to be involved in diabetes management. Conversely, access to technologies and flexibility in parents’ work environment facilitated involvement. Overall, these themes align with previous research that demonstrated social determinants (e.g., food insecurity, social marginalization) are associated with T1D health outcomes (Cummings et al., 2018; Mendoza et al., 2018) and reinforce the focus on addressing the social determinants of health to reduce disparities in health outcomes among racial/ethnic minority children (Thornton et al., 2016). Indeed, previous intervention research showed that social needs screening (e.g., employment problems, food insecurity, insurance) and navigation services provided in a pediatric primary care setting reduced social needs and improved health outcomes among children without diabetes (Gottlieb et al., 2016).

Motivation

We could not identify any other study conducted with a large proportion of racial/ethnic minority parents that examined the role of parental beliefs in their involvement in children’s diabetes management. The current study findings suggest that exploring parental beliefs about their child having a normal life and about prioritizing children’s health needs over other competing demands may be helpful to address parental involvement in young children’s diabetes management. These beliefs can be reinforced in clinical settings and in behavioral interventions when they are associated with increased parental involvement. Alternatively, when parental concerns about their child having a normal life impede involvement, parents may benefit from learning strategies to help their child cope with negative emotions related to “feeling normal.” Such strategies could involve using developmentally appropriate communication to invite their child to talk about their feelings, statements to normalize their child’s feelings, and role-play to help children effectively navigate peer situations (Patton, Clements, George, & Goggin, 2016). However, given the importance of parental well-being for children’s outcomes (Jaser, 2011), this should not suggest that parents eliminate self-care. Mental health and health care professionals should guide parents in identifying strategies and sources of support to help them maintain involvement in their child’s diabetes and also attend to their own well-being.

Limitations

This study involves a small sample of African American and Latino parents, which may limit generalizability of findings. However, the sample size was appropriate for qualitative research, and saturation was reached and was used as a criterion to discontinue recruitment (Wu et al., 2016). In addition, only parents who reported their primary language was English were included, and this might have resulted in restricted levels of acculturation of the participants. Different experiences may be important for parents with diverse levels of acculturation and for whom English is not their primarily language. Finally, given this study’s focus on young children ages 5–9, their perspectives were not obtained, which could add clinically important information.

Conclusions

The COM-B model can provide a helpful framework for considering multiple types of supports or challenges that African American and Latino families experience with regard to diabetes management. The themes identified in this qualitative study may guide a more detailed quantitative examination of associations of psychological, social, environmental, and motivational factors with parental involvement and responsibility sharing in T1D management. These study results could be used to inform the design of multilevel behavioral interventions that aim to maximize parental involvement in T1D management among African American and Latino families. Future research conducted separately among each racial/ethnic group may reveal unique parenting factors that contribute to differential disparities in health outcomes among these groups that could inform culturally tailored interventions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Disorders (DP3DK113236 to A.M.B.).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.