-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Colleen Stiles-Shields, Colleen F Bechtel Driscoll, Joseph R Rausch, Grayson N Holmbeck, Friendship Quality Over Time in Youth With Spina Bifida Compared to Peers, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 44, Issue 5, June 2019, Pages 601–610, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsy111

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Examine friendship qualities (i.e., control, prosocial skills, positive affect, support, companionship, conflict, help, security, and closeness) and perceived self-efficacy in friendships of children with spina bifida (SB) and chosen peers over time through observed behaviors and self-report.

Families of children with SB (aged 8–15) were asked to invite the child’s “best friend” to participate in-home assessment visits; 127 friendship dyads were included in the current study. Mixed-effects models were used to examine children with SB and their peers across age on observed behaviors and self-reported data about their friendships.

For observed behaviors, peers displayed more control (p = .002) and prosocial behaviors (p = .007) with age than youth with SB. Male peers displayed higher control in their interactions as they aged (p = .04); and males with SB maintained their level of prosocial behaviors with age, compared to an increase in prosocial behaviors with age for all other groups (p = .003). For self-reported data, there was no evidence to suggest significant differences in friendship qualities across age (ps ≥ .2), with the exception of increased help (p = .002). Female peers reported increases in companionship across age compared to the other groups (p = .04).

Differing from previous examinations of social characteristics in SB, most longitudinal trends in friendship qualities did not differ for youth with SB compared to their peers. Promotion of this existing social strength may be a key intervention target for future strategies that promote positive outcomes for youth with SB.

Introduction

Spina bifida (SB) is the most common birth defect affecting the central nervous system, with occurrence in roughly 3 of every 10,000 live births (Parker et al., 2010). Youth with SB must manage an extremely complex medical treatment regimen (e.g., surgery, bladder, and bowel control) while also experiencing a variety of cognitive and psychosocial comorbidities (e.g., motor and sensory neurological deficits, pain, psychosocial difficulties, depressive symptoms; Copp et al., 2015). Across development, youth with SB must interact with a growing social environment to achieve typical milestones and effectively self-manage their complex medical needs. This social environment includes, but is not limited to: health-care providers, new classmates or coworkers, and potential friends, roommates, or partners (Betz, Smith, Macias, & Deavenport-Saman, 2015). This social mastery may be more complex for youth with SB, given a variety of factors associated with the condition. For example, neuropsychological differences may be present, such as attention difficulties and language issues (e.g., cocktail party syndrome; Rose & Holmbeck, 2007; Tew, 1979). Additionally, psychosocial factors, such as having less afterschool social interactions than typically developing (TD) peers, have also been found to impact social interactions and skills for youth with SB (Holmbeck et al., 2003). Given the importance of social factors, understanding the social strengths, and vulnerabilities of youth with SB may highlight possible targets for intervention across the development from childhood through adolescence.

Friendship qualities are defined as the style and tone of the interactions a child and friend(s) may each contribute to their relationship (e.g., conflict, caring, security, companionship, etc.; Cunningham, Thomas, & Warschausky, 2007). Positive friendship qualities in adolescence have been specifically identified as long-term predictors of adult health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in TD populations (Allen, Uchino, & Hafen, 2015). For youth with chronic conditions, positive associations with health and psychological targets, such as medical adherence and HRQOL, have also been noted for friendship qualities (Helgeson & Holmbeck, 2015; Helms, Dellon, & Prinstein, 2015; La Greca, Bearman, & Moore, 2002). Pediatric research tends to focus on social adjustment, social support, and psychosocial functioning to the exclusion of the quality of friendships in youth with chronic conditions (Helms et al., 2015). Research on SB has followed this trend, to the exclusion of examining friendship qualities with peers. This trend provides an important opportunity to specifically examine friendship qualities, a potentially already existing strength that may be bolstered, in pediatric populations.

To date, only two studies have explicitly examined peer friendship qualities in youth with SB compared to TD peers. First, Cunningham et al. (2007) found that children (with SB and cerebral palsy; 6- to 12-years old) and their parents reported less validation and caring in their friendships as compared to similarly aged peers. However, there was no evidence to suggest differences in the domains of social withdrawal, conflict, and betrayal (Cunningham et al., 2007). Second, and based on cross-sectional data from the current study, Devine et al. (2012) utilized a tri-component model of social competence (i.e., social adjustment, social performance, and social skills; Cavell, 1990) to examine the quality of dyadic relationships between youth with SB (8- to 15-years old) and their chosen peers (i.e., an unrelated “best friend”). While many similarities between youth with SB and their peers were identified (e.g., peer acceptance, conflict, and help in friendships), the reported quality and reciprocation of friendships were lower for youth with SB in domains such as companionship, security, and closeness. Further, youth with SB experienced lower perceived social self-efficacy in their interactions with friends, which may impact the experience of friendship quality (Devine et al., 2012). These two studies suggest that youth with SB experience both similarities and deficits in friendship qualities compared to their peers; however, the research remains limited.

The previous research about friendship qualities for youth with SB highlights important reasons to better understand this construct. First, friendship qualities have been identified as having potentially positive and negative impacts on medical adherence and quality of life in other pediatric conditions (Helms et al., 2015). Indeed, the promotion of specific qualities of friendship may stand as a potential target of intervention that could improve health and psychological factors for youth with SB over time. Second, the existing literature on quality of friendships in SB is cross-sectional, making it unclear how friendship qualities are experienced over time as youth age. Although youth with SB have previously demonstrated a delay in milestone achievement (Devine, Wasserman, Gershenson, Holmbeck, & Essner, 2011; Lennon, Murray, Bechtel, & Holmbeck, 2015; Zukerman, Devine, & Holmbeck, 2011), it is not yet clear whether deficits identified in friendships persist across development. Therefore, longitudinal research is needed to better understand the developmental trajectory of friendship qualities for youth with SB, which will facilitate the identification of intervention targets.

The purpose of the current study is to extend previous cross-sectional findings on friendship qualities (Devine et al., 2012) by examining friendship qualities of youth with SB to chosen peers as they age. Using a multimethod (i.e., observation and questionnaire) methodology, we examined: (a) the observed behaviors of youth with SB and their peers that reflect the presence of specific friendship qualities (i.e., control [ability to attract attention to access desired resources from friend], prosocial skills [behaviors that lead to positive social outcomes, such as acceptance], and positive affect [the expression of affect that aids in appropriate social interactions]; Holbein et al., 2014); and (b) the reports of youth with SB and their peers on the qualities of their current friendships (i.e., support [emotional closeness and openness], companionship [spending enjoyed, free time together], conflict [disagreements or annoyance], help [aid and protection from victimization], security [trust and reliance], and closeness [sense of affection and attachment]; Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994; Slavin, 1991) and their perceived self-efficacy (belief in one’s ability to achieve specific outcomes; Wheeler & Ladd, 1982) in friendships. These outcomes were examined over time, as defined by increase in age, and with the predictors of participant type (i.e., youth with SB vs. peers), sex, and the interaction of participant type × sex. With the exception of conflict (which has been correlated with the termination of friendships; Bukowski et al., 1994), we hypothesized that friendship qualities would increase with age for the sample as a whole due to maturation and anticipated increases in reliance on friendship qualities with development (i.e., seeking support more from peers than family over time; Rubin et al., 2004). Consistent with a delay and catch-up in milestone attainment (Devine et al., 2011; Lennon, Klages, Amaro, Murray, & Holmbeck, 2015; Zukerman et al., 2011), we hypothesized that differences in friendship qualities would diminish with age between youth with SB and their peers. Additionally, despite established sex differences in the friendships of TD children (Hall, 2011), few sex differences have been identified for friendship qualities in youth with SB (Cunningham et al., 2007; Devine et al., 2012). We therefore hypothesized that the current analyses would follow this trend for SB, with no significant sex differences. Finally, we explored the interaction effects for participant by sex.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited for an ongoing, longitudinal program of research examining the neurocognitive, family, and social development of children with SB (Lennon, Klages, et al., 2015). Participants were eligible for inclusion at Time One (T1) if they: (a) had a diagnosis of SB; (b) were 8- to 15-years old; (c) resided within 300 miles of Chicago; (d) did not have comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions; and (e) were able to speak and read English or Spanish. Chosen peers were eligible for inclusion if they: (a) were 6- to 17-years old at T1 (i.e., ± 2 years from the participant age range; however, if a family recruited a peer outside of this age range, they were included); and (b) were able to speak and read English or Spanish. At T1, 140 participants with SB and 120 chosen peers were recruited (Devine et al., 2012). Over the course of the three time points, 127 participants with SB had a chosen peer participate at least once. The current longitudinal analyses included data from the youth with SB (T1 = 125, T2 = 106; T3 = 75) and their peers (T1 = 122, T2 = 98, T3 = 63), with a decrease in sample size due primarily to roughly 25% of the sample of youth with SB aging beyond 17 years of age at T3 (initiating the “young adult” assessment protocol, which did not include peer assessment). Of these included dyads, children with SB at T1 ranged in age from 8 to 15 years (M = 11.28 ± 2.44 years), and 54.3% were female. At T1, peers ranged in age from 6 to 22 years (M = 11.11 ± 3.04 years), 53.5% were female, and four had SB (the remaining peers were TD). Table I describes SB-specific sample characteristics and the demographics of both groups.

Children With Spina Bifida and Their Peer: Demographic and Condition-Specific Characteristics

| Demographics . | Children with SB (n = 127) . | Peers (n = 127) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at T1, M (SD) | 11.28 (2.44) | 11.11 (3.04) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 69 (54.3) | 68 (53.5) |

| Female | 56 (44.1) | 54 (42.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 69 (54.3) | 74 (58.3) |

| Hispanic | 34 (26.8) | 26 (20.5) |

| African American | 16 (12.6) | 12 (9.4) |

| Other | 8 (6.3) | 8 (6.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.5) |

| SB type, n (%) | ||

| Myelomeningocele | 111 (87.4) | – |

| Other | 16 (12.6) | – |

| Lesion level, n (%) | ||

| Thoracic | 20 (16.1) | – |

| Lumbar | 64 (51.6) | – |

| Sacral | 38 (30.6) | – |

| Unknown/not reported | 5 (1.7) | – |

| Shunt status, n (%) | ||

| Present | 98 (77.2) | – |

| Not present | 29 (22.8) | – |

| Ambulation, n (%) | ||

| No assistance | 14 (11.6) | – |

| KAFO or AFO | 35 (28.9) | – |

| Wheelchair | 72 (59.5) | – |

| FSIQ, M (SD) | 86.3 (19.7) | – |

| Demographics . | Children with SB (n = 127) . | Peers (n = 127) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at T1, M (SD) | 11.28 (2.44) | 11.11 (3.04) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 69 (54.3) | 68 (53.5) |

| Female | 56 (44.1) | 54 (42.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 69 (54.3) | 74 (58.3) |

| Hispanic | 34 (26.8) | 26 (20.5) |

| African American | 16 (12.6) | 12 (9.4) |

| Other | 8 (6.3) | 8 (6.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.5) |

| SB type, n (%) | ||

| Myelomeningocele | 111 (87.4) | – |

| Other | 16 (12.6) | – |

| Lesion level, n (%) | ||

| Thoracic | 20 (16.1) | – |

| Lumbar | 64 (51.6) | – |

| Sacral | 38 (30.6) | – |

| Unknown/not reported | 5 (1.7) | – |

| Shunt status, n (%) | ||

| Present | 98 (77.2) | – |

| Not present | 29 (22.8) | – |

| Ambulation, n (%) | ||

| No assistance | 14 (11.6) | – |

| KAFO or AFO | 35 (28.9) | – |

| Wheelchair | 72 (59.5) | – |

| FSIQ, M (SD) | 86.3 (19.7) | – |

Note. Spina bifida characteristics defined by the medical chart. In the case of missing data, mother report of characteristics was used. One participant did not have characteristics reported by the medical chart or mother. AFO = Ankle Foot Orthosis; FSIQ = Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; KAFO = Knee Angle Foot Orthosis; M = mean; SB = spina bifida; SD = standard deviation; T1 = Time 1.

Children With Spina Bifida and Their Peer: Demographic and Condition-Specific Characteristics

| Demographics . | Children with SB (n = 127) . | Peers (n = 127) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at T1, M (SD) | 11.28 (2.44) | 11.11 (3.04) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 69 (54.3) | 68 (53.5) |

| Female | 56 (44.1) | 54 (42.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 69 (54.3) | 74 (58.3) |

| Hispanic | 34 (26.8) | 26 (20.5) |

| African American | 16 (12.6) | 12 (9.4) |

| Other | 8 (6.3) | 8 (6.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.5) |

| SB type, n (%) | ||

| Myelomeningocele | 111 (87.4) | – |

| Other | 16 (12.6) | – |

| Lesion level, n (%) | ||

| Thoracic | 20 (16.1) | – |

| Lumbar | 64 (51.6) | – |

| Sacral | 38 (30.6) | – |

| Unknown/not reported | 5 (1.7) | – |

| Shunt status, n (%) | ||

| Present | 98 (77.2) | – |

| Not present | 29 (22.8) | – |

| Ambulation, n (%) | ||

| No assistance | 14 (11.6) | – |

| KAFO or AFO | 35 (28.9) | – |

| Wheelchair | 72 (59.5) | – |

| FSIQ, M (SD) | 86.3 (19.7) | – |

| Demographics . | Children with SB (n = 127) . | Peers (n = 127) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at T1, M (SD) | 11.28 (2.44) | 11.11 (3.04) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 69 (54.3) | 68 (53.5) |

| Female | 56 (44.1) | 54 (42.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 69 (54.3) | 74 (58.3) |

| Hispanic | 34 (26.8) | 26 (20.5) |

| African American | 16 (12.6) | 12 (9.4) |

| Other | 8 (6.3) | 8 (6.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.5) |

| SB type, n (%) | ||

| Myelomeningocele | 111 (87.4) | – |

| Other | 16 (12.6) | – |

| Lesion level, n (%) | ||

| Thoracic | 20 (16.1) | – |

| Lumbar | 64 (51.6) | – |

| Sacral | 38 (30.6) | – |

| Unknown/not reported | 5 (1.7) | – |

| Shunt status, n (%) | ||

| Present | 98 (77.2) | – |

| Not present | 29 (22.8) | – |

| Ambulation, n (%) | ||

| No assistance | 14 (11.6) | – |

| KAFO or AFO | 35 (28.9) | – |

| Wheelchair | 72 (59.5) | – |

| FSIQ, M (SD) | 86.3 (19.7) | – |

Note. Spina bifida characteristics defined by the medical chart. In the case of missing data, mother report of characteristics was used. One participant did not have characteristics reported by the medical chart or mother. AFO = Ankle Foot Orthosis; FSIQ = Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; KAFO = Knee Angle Foot Orthosis; M = mean; SB = spina bifida; SD = standard deviation; T1 = Time 1.

Procedure

This study was approved by university and hospital Institutional Review Boards (IRB). Time points (i.e., T1, T2, and T3) occurred within 2-year windows, meaning that roughly 2 years passed between each time point. At T1, data were collected across two in-home assessment sessions conducted by two trained research assistants. At T2 and T3, data were collected during single in-home assessment sessions. In compliance with IRB approval, informed child assent and parental consent were obtained prior to all data collection. For peer participation, informed child assent was obtained in person during the home visit, and parental consent was obtained in person or via mail prior to the in-home assessment session involving the peer. Participants and their families were not required to select the same peer at each time point; therefore, if a new peer was selected at T2 or T3, informed child assent and parental consent were again obtained.

During the first in-home assessment session, children with SB and their parents were first provided with the peer inclusion criteria (see Participants section), and then asked to invite the child’s “closest” friend meeting these criteria to the next in-home assessment session. Parents were also asked to contact the peer’s parent(s) to obtain consent for research staff to contact the family of the peer with more information. During the second in-home assessment session, the child and peer completed self-report questionnaires individually, structured interview tasks, and an observed interaction as a dyad that was video recorded. Families and the peers were compensated for their time at all time points with gifts (e.g., reusable water bottle) and monetary compensation ($150 for families; $50 for peers).

Measures

Demographics

Parents of the children with SB completed a questionnaire detailing the child’s demographic information (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, grade in school, etc.). The peers completed a questionnaire to detail their own demographic information.

Observations of Behavior

The children with SB and their peers completed video-taped interactions during the home visit at each time point. At T1, the pair completed four structured tasks: (a) a toy-ranking activity, (b) discussion of an unfamiliar object, (c) discussion and planning of an adventure, and (d) discussion of social conflicts. At T2, the tasks included: (a) an interactive game, (b) discussion and planning of a news broadcast, (c) discussion and planning of a vacation, and (d) discussion of social conflicts. At T3, the tasks were: (a) an interactive game, (b) discussion around provided social vignettes, (c) discussion and planning of a birthday party, and (d) discussion of social conflicts. At each time point, the order of the tasks was randomly assigned.

The Peer Interaction Macro-coding System (PIMS) was used to code the peer interactions at each time point (Holbein et al., 2014). The PIMS is comprised of four scales: control (two items), prosocial skills (six items), positive affect (six items), and conflict (five items). The video-taped interactions were coded by two separate coders, including trained undergraduate and graduate students. To assess interrater reliability, intraclass reliability correlations (ICCs) were computed for children with SB and their peers for each scale and across time. All ICCs were adequate (as defined as 0.60 or greater; Kieffer, Cronin, & Fister, 2004), with the exception of the conflict scale at T2 and T3 (ICC = 0.55–0.59). Therefore, the conflict scales for children with SB and their peers were excluded from the analyses. To assess scale reliability, a Cronbach’s alpha of .60 or above was considered adequate. Scale reliability was adequate for all scales across children with SB and their peers, across time, with the exception of the peer control scale at T3 (α = .51). Given that this scale reliability was impacted by low variability in ratings at T3 compared to the previous time points, this scale was retained in the analyses.

Questionnaires

Children with SB were asked to report if their selected “best friend” was the same person as from the previous time point. Both children with SB and their peer were also asked to report whether the other person was their current “best friend” and how close they felt to the other person on a 10-point Likert scale (i.e., 1–10).

The Children’s Self-Efficacy for Peer Interaction Scale (CSPI) is a self-report measure assessing perceived self-efficacy in social situations (Wheeler & Ladd, 1982). The scale consists of 22 items describing peer interactions, clustered into two groups: conflict and nonconflict. Each item describes a social situation, followed by an incomplete statement requiring the participant to evaluate his/her ability to verbally persuade another based on the situation. Respondents are asked to identify how hard each item is for them (i.e., very hard, hard, easy, or very easy). For this study, four items were excluded (numbers 15, 16, 18, and 20 from the original scale) because the wording was age-inappropriate (e.g., “using your play area”). The CSPI demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in the current sample, across time (children with SB: T1 α = .82, T2 α = .87, T3 α = .91; peers: T1 α = .86, T2 α = .87, T3 α = .88).

The Emotional Support Questionnaire (ESQ) is an extension of Slavin’s Perceived Emotional/Personal Support Scale (PEPSS; Slavin, 1991), a measure of emotional support for adolescents 14–19 years of age. The ESQ is comprised of the PEPSS, as well as three additional items. For the purposes of the current study, only responses pertinent to friends were included. Individuals were asked to nominate three friends, rating each relationship on four items: how much they talked with the individual about personal concerns, how close they felt to the individual, how much the individual talked to the respondent, and how satisfied they were with the support they received. The three items added for this study included the following queries: (a) how often they got upset with or mad at each other, (b) how much they played around and had fun together, and (c) the level of certainty that this relationship would last no matter what. The ESQ demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in the current sample, across time (children with SB: T1–T3 peer support αs = .88–.92; peers: T1–T3 peer support αs = .87–.89).

The Friendship Activity Questionnaire (FAQ) is based on Bukowski’s Friendship Qualities Scale (Bukowski et al., 1994). The FAQ consists of 46 items across five scales of friendship qualities: companionship, conflict, help, security, and closeness. Respondents are asked to rate how true each statement is for their friendship on a five-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = Not True to 5 = Really True). Participants in the current study were asked to answer the questions in reference to the other youth participant on the home visit (i.e., the child with SB answered the FAQ about their chosen best friend, and vice versa). The FAQ demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in the current sample, across time (children with SB: T1–T3 companionship αs = .64–.96, T1–T3 conflict αs = .78, T1–T3 help αs = .89–.91, T1–T3 security αs = .77–.85, T1–T3 closeness αs = .81–.85; peers: T1–T3 companionship αs = .67–.75, T1–T3 conflict αs = .73–.74, T1–T3 help αs = .89–.92, T1–T3 security αs = .76–.84, T1–T3 closeness αs = .80–.89).

Data Analysis

To characterize the friendship dyads (i.e., the friendship between each child with SB and his/her selected peer who participated in the home visit), t-tests and chi-square analyses were used to compare the reports of children with SB versus the reports of their peers regarding the status of their current friendship (i.e., if they are “best friends” and how close they are to their friend) at each time point.

Change in outcome variables (i.e., PIMS, CSPI, ESQ, and FAQ) across time were examined using the participant’s age as the predictor variable within mixed-effects models (SAS Institute Inc.). Age was selected as the means to define time as it provides more insight into these qualities across development, as opposed to the arbitrary time points of the study assessment schedule. Age spanned 8 to 17 years of age for youth with SB (which includes the age ranges of participants at T1: 8–15, T2: 10–17, and T3: 12–19, with the exception of data from 18- and 19-year olds at T3 due to the lack of peer participation for young adult participants) and 6 to 22 years of age for peers (due to the extended range in peer participants at T1; please see Participants section). The mixed-effects models used were individual change models that allowed for straight-line change and also allowed for fixed and random effects for the individual intercepts and slopes across age. Each participant contributed at most three time points to the analysis (i.e., T1–T3), although there was generally overlap across ages (e.g., a participant may have contributed data at ages 8, 10, and 12, and overlapped with other participants at these ages). In some models, the variance for the slope random effects was estimated to be zero; in these cases, we re-fit the model after excluding the slope random effect. Consistent with our aims and hypotheses, we investigated models for change with: (a) no predictors (indicating change in slope across age overall, meaning change for the total sample across age), (b) participant type (i.e., youth with SB vs. peer) as a predictor of the intercept and slope (i.e., examining differences in friendship qualities between youth with SB and their peers across age), (c) sex as a predictor of the intercept and slope (i.e., examining sex differences for friendship qualities), and (d) the interaction of participant type × sex as a predictor of intercept and slope in addition to all lower-order effects. p-Values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Status of Friendship with Peer

The same peer was not required to be selected at each time point. Indeed, it was anticipated that a child with SBs identified “best friend” might not be stable across development. At T2, 49 children with SB (48%) reported selecting the same peer as at T1; at T3, 30 children with SB (40%) reported selecting the same peer as at T2. At all three time points, there was no evidence to suggest a difference in agreement on whether the child with SB and the peer were best friends (ps > .3). There was also no evidence to suggest differences in how close the children with SB and peers rated their friendships at any time point (1–10 self-report question of dyad closeness; ps > .1).

Peer Interactions

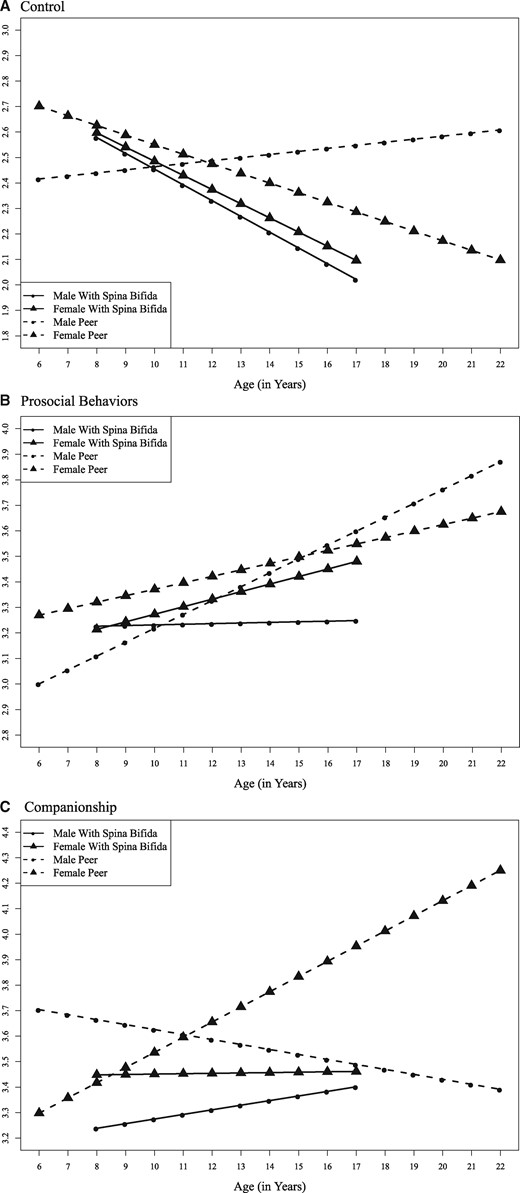

Table II summarizes the results for growth models examining outcomes across age. Growth models examining observed behaviors indicated significant changes for control, prosocial behaviors, and positive affect (ps ≤ .001; see “Peer Interactions” section of table). Specifically, for the entire sample as a whole (i.e., “No Predictor” column of table): the amount of control (i.e., ability to attract attention to access desired resources from friend) decreased with age (Δ m =−0.032), whereas prosocial behaviors (i.e., behaviors that lead to positive social outcomes, such as acceptance; Δ m = 0.026) and positive affect (i.e., the expression of affect that aids in appropriate social interactions; Δ m = 0.022) increased with age. In terms of participant type (column of same name in table): peers displayed more control (Δ m = 0.048; p = .002) and prosocial behaviors (Δ m = 0.023; p = .007) with age than youth with SB. This difference emerged with age, such that peers would have a higher control score by about 0.05 and a higher prosocial behavior score by about 0.02, per increase in year of age on the PIMS. There was no evidence to suggest that sex predicted observable behavior outcomes with age (ps ≥ .09). However, significant participant type × sex interaction effects were detected, such that: (a) male peers displayed higher control in their interactions as they aged, compared to a decline in control with age for all other groups (Δ m = −0.056; p = .04), and (b) males with SB maintained their level of prosocial behaviors with age, compared to an increase in prosocial behaviors with age for all other groups (Δ m = −0.056; p = .003). To aid in interpretation of these interaction effects, Figure 1 displays the significant interactions of participant type × sex for peer interactions (i.e., control and prosocial behaviors) and friendship qualities (i.e., companionship; described below).

| . | Predictor of slope . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome . | No predictor . | Participant typea . | Sexa . | Participant type × sexa . |

| Peer interactions | ||||

| PIMS control | −0.032*** | 0.048** | −0.023 | −0.056* |

| PIMS prosocial behaviors | 0.026*** | 0.023** | 0.002 | −0.056** |

| PIMS positive affect | 0.022*** | 0.002 | 0.015 | −0.022 |

| Social self-efficacy, emotional support | ||||

| CSPI | 0.013 | −0.017 | −0.024 | −0.050 |

| ESQ number of identified support figures | −0.009 | 0.006 | 0.012 | −0.025 |

| ESQ perceived support | 0.022** | −0.016 | −0.019 | −0.003 |

| Friendship qualities | ||||

| FAQ companionship | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.043 | 0.096* |

| FAQ help | 0.035** | 0.007 | 0.004 | −0.015 |

| FAQ security | 0.012 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.022 |

| FAQ closeness | −0.009 | 0.02 | −0.012 | −0.021 |

| . | Predictor of slope . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome . | No predictor . | Participant typea . | Sexa . | Participant type × sexa . |

| Peer interactions | ||||

| PIMS control | −0.032*** | 0.048** | −0.023 | −0.056* |

| PIMS prosocial behaviors | 0.026*** | 0.023** | 0.002 | −0.056** |

| PIMS positive affect | 0.022*** | 0.002 | 0.015 | −0.022 |

| Social self-efficacy, emotional support | ||||

| CSPI | 0.013 | −0.017 | −0.024 | −0.050 |

| ESQ number of identified support figures | −0.009 | 0.006 | 0.012 | −0.025 |

| ESQ perceived support | 0.022** | −0.016 | −0.019 | −0.003 |

| Friendship qualities | ||||

| FAQ companionship | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.043 | 0.096* |

| FAQ help | 0.035** | 0.007 | 0.004 | −0.015 |

| FAQ security | 0.012 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.022 |

| FAQ closeness | −0.009 | 0.02 | −0.012 | −0.021 |

Note. Table results indicate the change in slope for each unit change of 1 year. CSPI = The Children’s Self-Efficacy for Peer Interaction Scale; ESQ = Emotional Support Questionnaire; FAQ = The Friendship Activity Questionnaire; M = estimated marginal mean; PIMS = Peer Interaction Macro-Coding System; SB = spina bifida; SE = standard error.

aParticipant type and sex effects were examined in isolation, whereas interaction effects included all lower-order effects in model.

*p < .05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001.

| . | Predictor of slope . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome . | No predictor . | Participant typea . | Sexa . | Participant type × sexa . |

| Peer interactions | ||||

| PIMS control | −0.032*** | 0.048** | −0.023 | −0.056* |

| PIMS prosocial behaviors | 0.026*** | 0.023** | 0.002 | −0.056** |

| PIMS positive affect | 0.022*** | 0.002 | 0.015 | −0.022 |

| Social self-efficacy, emotional support | ||||

| CSPI | 0.013 | −0.017 | −0.024 | −0.050 |

| ESQ number of identified support figures | −0.009 | 0.006 | 0.012 | −0.025 |

| ESQ perceived support | 0.022** | −0.016 | −0.019 | −0.003 |

| Friendship qualities | ||||

| FAQ companionship | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.043 | 0.096* |

| FAQ help | 0.035** | 0.007 | 0.004 | −0.015 |

| FAQ security | 0.012 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.022 |

| FAQ closeness | −0.009 | 0.02 | −0.012 | −0.021 |

| . | Predictor of slope . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome . | No predictor . | Participant typea . | Sexa . | Participant type × sexa . |

| Peer interactions | ||||

| PIMS control | −0.032*** | 0.048** | −0.023 | −0.056* |

| PIMS prosocial behaviors | 0.026*** | 0.023** | 0.002 | −0.056** |

| PIMS positive affect | 0.022*** | 0.002 | 0.015 | −0.022 |

| Social self-efficacy, emotional support | ||||

| CSPI | 0.013 | −0.017 | −0.024 | −0.050 |

| ESQ number of identified support figures | −0.009 | 0.006 | 0.012 | −0.025 |

| ESQ perceived support | 0.022** | −0.016 | −0.019 | −0.003 |

| Friendship qualities | ||||

| FAQ companionship | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.043 | 0.096* |

| FAQ help | 0.035** | 0.007 | 0.004 | −0.015 |

| FAQ security | 0.012 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.022 |

| FAQ closeness | −0.009 | 0.02 | −0.012 | −0.021 |

Note. Table results indicate the change in slope for each unit change of 1 year. CSPI = The Children’s Self-Efficacy for Peer Interaction Scale; ESQ = Emotional Support Questionnaire; FAQ = The Friendship Activity Questionnaire; M = estimated marginal mean; PIMS = Peer Interaction Macro-Coding System; SB = spina bifida; SE = standard error.

aParticipant type and sex effects were examined in isolation, whereas interaction effects included all lower-order effects in model.

*p < .05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001.

Participant type × sex interactions across age. (A) Observed behavior of control; (B) observed prosocial behaviors; and (C) reported level of companionship received in friendships. The interpretations of the figures occurred in the overlap in ages (i.e., 8–17), but all included ages for the groups are shown (i.e., Youth with spina bifida = 8–17; Peers = 6–22).

Social Self-Efficacy and Emotional Support

There was no evidence to suggest that social self-efficacy changed with age, or that participant type, sex, or participant type × sex predicted change (ps ≥ .08; see “Social Self-Efficacy, Emotional Support” section of Table II). Perceived emotional support from friends increased for the sample as a whole across age (Δ m = 0.022; p = .01). However, there was no evidence to suggest a change in the number of supportive friends, nor the level of support received across time as predicted by participant type, sex, or participant type × sex (ps ≥ .3).

Friendship Qualities

There was no evidence to suggest significant changes in friendship qualities across age (ps ≥ .2), with the exception of increased help (i.e., aid and protection from victimization) from friends (Δ m = 0.035; p = .002). There was also no evidence to suggest a significant predictive role of participant type or sex for friendship qualities (ps ≥ .08). However, there was a significant participant type × sex interaction effect across age for companionship (spending enjoyed, free time together), such that female peers reported greater increases in companionship compared to the other groups (Δ m = 0.096; p = .04; see Figure 1C). No other significant predictive interactions were selected for the outcome of friendship qualities across age (ps ≥ .5).

Discussion

The present study identified friendship qualities of youth with SB across age using a multimethod (i.e., observation and questionnaire) approach. Our hypothesis that most friendship qualities would increase with age was confirmed for prosocial behaviors and positive affect, however control decreased with age. Self-report data for the entire sample also supported this hypothesis, indicating an increase in perceived level of support from friends with age, as well as receiving help in friendships. Further, while we anticipated that differences between youth with SB and peers would diminish with age, peers maintained higher ratings of control and prosocial behaviors than youth with SB. Consistent with our sex-related hypotheses based on previous examinations of friendship in SB (Cunningham et al., 2007; Devine et al., 2012), there were no sex differences in friendship qualities with age. Finally, the exploratory examination of interaction effects of participant type by sex across age indicated differences in control, prosocial behaviors, and companionship. Specifically: (a) higher control was displayed by male peers in their interactions as they aged compared to all other groups (i.e., males with SB, females with SB, and female peers), (b) increasing prosocial behaviors were displayed for all groups except for males with SB, who maintained a relative homeostasis in their level of prosocial behaviors with age, and (c) female peers reported increases in companionship with age compared to the three other groups.

Previous cross-sectional research indicates that youth with SB report less validation, caring, and reciprocation in their friendships, but similar levels of conflict, withdrawal, and help compared to their TD peers (Cunningham et al., 2007; Devine et al., 2012). The current longitudinal study extends this line of research, examining these qualities with a larger sample size and across development. Self-reported friendship qualities did not differ for youth with SB compared to their peers as they aged. Of note, an interaction effect was detected such that female peers reported an increase in companionship in friendships compared with all other groups. This is in line with previous findings comparing healthy males and females to youth with diabetes, suggesting that dealing with a chronic health condition may interfere with typical sex-specific trajectories of friendship (i.e., a normative increase in friendship qualities with age particularly for females; Helgeson, Reynolds, Escobar, Siminerio, & Becker, 2007). Overall, these findings are consistent with longitudinal comparisons of youth with chronic pediatric conditions (i.e., oncology history, sickle cell disease, and rheumatoid arthritis) to TD peers that demonstrate few differences in friendships for these populations (Noll, Kiska, Reiter-Purtill, Gerhardt, & Vannatta, 2010; Reiter-Purtill, Gerhardt, Vannatta, Passo, & Noll, 2003; Reiter-Purtill, Vannatta, Gerhardt, Correll, & Noll, 2003).

Observed interactions indicated that peers demonstrated significantly more control and prosocial behaviors with age. As defined by the PIMS, control refers to the ability to attract the attention of a friend and gain submission in the interaction to achieve a goal or increase self-esteem, whereas prosocial behaviors refer to actions that promote peer acceptance (e.g., empathy, asking questions, etc.; Holbein et al., 2014). It is possible that these select observed behavioral differences across development echo previous findings indicating delays, but eventual attainment of milestones in youth with SB (Devine et al., 2011; Lennon, Klages, et al., 2015; Zukerman et al., 2011). Further, differences in observed behaviors for this sample have previously been associated with parent ratings of the youths’ abilities to initiate social plans (Holbein et al., 2014). These differences may also be driven by the interaction of participant type and sex. Indeed, male peers were found to have more observed control in interactions, whereas males with SB appeared to maintain a relatively static amount of prosocial behaviors over time. These findings suggest that prosocial behavior development could be promoted in interventions in boys with SB. However, while these interactions are worth noting and exploring, we are hesitant to overinterpret their meaning. Indeed, while statistically significant, the clinical significance of these findings is likely minimal (i.e., a change in PIMS score of a half point or less with each year aged; see Table II).

Given the frequent emphasis on social deficits or vulnerabilities in the literature regarding youth with SB (Holmbeck & Devine, 2010; Shields, Taylor, & Dodd, 2008), the current findings are encouraging. Indeed, a focus on friendship qualities may highlight specific strengths for youth with SB across development, as opposed to other previously examined social factors (e.g., total number of friends). It is of note that the current findings diverge from previous studies of friendship qualities in youth with SB (Cunningham et al., 2007), including a cross-sectional investigation of the same sample (Devine et al., 2012). The previous studies identified some vulnerabilities for youth with SB in their friendship qualities and little to no sex differences. These differences with the current findings may be due to differences in the methodologies (i.e., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal). Given previously noted delays in milestone achievement, friendship qualities in youth with SB may be best examined via a longitidunal approach.

If friendship qualities potentially impact medical adherence and HRQOL in pediatric conditions (Helms et al., 2015) and in TD populations (Allen et al., 2015), the current findings highlight potential targets of intervention for some youth with SB. While speculative, this information could potentially focus intervention efforts. For example, it may be beneficial to focus on promoting currently available social networks across youth (Betz et al., 2015), rather than attempting to address more challenging targets, such as fostering overall social skills across development. Future research should investigate SB outcomes bolstered through the strengths-based lens of existing positive friendship qualities, and the possible predictive or mediational roles these qualities may have for medical adherence and quality of life.

It is important to consider the current findings in light of potential limitations. First, the sample was comprised of youth with SB who agreed to participate in longitudinal research. It is possible that this sample is unique. For example, they may be especially adept at behaviors that promote positive friendship qualities, compared to other youth with SB who may display more behaviors consistent with social deficits (Holmbeck & Devine, 2010). Second, the exclusion of peers starting when the participants reach age 18 may have impacted the findings. Indeed, it is unclear how the trajectory of an even older sample would compare to the current findings. It is possible that more difficulties arise in identifying a “best friend” during young adulthood due to milestone achievement discrepancies (i.e., TD peers reaching milestones ahead of those with SB). Finally, the current work examined friendship qualities primarily in the context of a single peer friendship (i.e., the chosen “best friend”), without requiring the same peer to participate across time. The evaluated friendships may therefore be quite variable (e.g., a close friendship of 7 years as opposed to a new friendship made within the last few months) and suffer from nonindependence (as the members of dyads likely have many similarities). Further, while a multimethod approach was employed, teacher and parent report of friendship qualities were not assessed. It is also unclear how the findings may generalize to other peer relationships, or if there would be agreement regarding friendship qualities across other adult respondents.

Such limits of generalizability highlight future directions for research. Specifically, comparisons of friendships and friendhip qualities among youth with SB and “best friends” to (a) TD youth and their “best friends” and (b) youth with other chronic conditions and their “best friends,” would enhance generalizability. These comparisons would also highlight which strengths, vulnerabilities, and qualities are unique to youth with SB versus those with pediatric chronic conditions versus those who are TD.

Through the use of a multimethod approach, the findings of the present study indicate that the majority of examined friendship qualities did not differ for youth with SB compared to their peers across development. While previous cross-sectional work highlighted some vulnerabilities for youth with SB in terms of friendship qualities (Cunningham et al., 2007; Devine et al., 2012), an examination across development indicates that positive friendship qualities appear to be a strength for some youth with SB. This finding is promising, as positive friendship qualities in youth have been identified as: (a) long-term predictors of adult HRQOL in TD populations (Allen et al., 2015), and (b) being associated with health and psychological targets (e.g., medical adherence; Helgeson & Holmbeck, 2015; Helms et al., 2015; La Greca et al., 2002). Therefore, promoting this existing social strength may be a key intervention target for future strategies that promote positive health-related and psychological outcomes for youth with SB.

Funding

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (R01 NR016235), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD048629), and the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (12-FY13–271). This study is part of an ongoing, longitudinal study.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Illinois Spina Bifida Association as well as staff of the spina bifida clinics at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Loyola University Medical Center, Riley Children’s Hospital, and Shriners Hospital for Children. We also thank the numerous undergraduate and graduate research assistants who helped with data collection and data entry. Finally, we would like to thank the parents, children, teachers, and health professionals who participated in this study.

References

SAS Institute Inc.