-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nan Zhou, Charissa S L Cheah, Yan Li, Junsheng Liu, Shuyan Sun, The Role of Maternal and Child Characteristics in Chinese Children’s Dietary Intake Across Three Groups, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 43, Issue 5, June 2018, Pages 503–512, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx131

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To examine whether mothers’ early-life food insecurity (ELFI), pressuring to eat feeding practices (PEP), and child effortful control (EC) are associated with child dietary intake within and across three Chinese ethnic groups.

Participants included 119 Chinese international immigrants in the United States, 230 urban nonmigrant, and 468 rural-to-urban migrant mothers and preschoolers in China. Mothers reported on their ELFI, PEP, and their children’s EC and dietary intake.

Controlling for maternal and child body mass index, age, and gender, multiple group path analyses revealed that maternal ELFI was positively associated with PEP in all groups, which in turn was positively associated with child unhealthy diet in all groups, but negatively associated with child fruits and vegetables (F&V) consumption in the urban nonmigrant group only. Also, EC was positively associated with child F&V diet for all groups. Moreover, the indirect effect of ELFI on children’s unhealthy diet through PEP was significant only for immigrant children with lower levels of EC, but not those with higher levels of EC.

Our findings highlighted the long-lasting effect of mothers’ ELFI on their feeding and child eating. Mothers’ pressuring to eat played a central role in the association between their past experiences and children’s diet. Also, children’s poor EC abilities might exacerbate the adverse effect of mothers’ ELFI through PEP, resulting in more unhealthy eating. These findings can contribute to the design of contextually based intervention/prevention programs that promote young children’s healthy eating through maternal feeding practices and children’s EC abilities.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a critical worldwide public health threat. Despite the stereotype of the slender Chinese, 23.5% of 4-year-old Chinese-American children were reported to be overweight or obese (Jain et al., 2012). The healthy migrant selection phenomenon reveals that recent immigrants have better health than natives, but the health advantage declines with increasing time in the United States owing to unfavorable dietary changes (Van Hook & Balistreri, 2007). Recent Chinese immigrants also tend to be unfamiliar with American diets and have limited resources available to prepare healthy meals for their children (Satia et al., 2000).

Interestingly, the healthy migrant selection phenomenon is also observed in intracountry migration within China (Chen, 2011). Comprehensive economic reforms since the 1980s have attracted huge influxes of rural residents, called internal migrants, to the cities. Meanwhile, about 39 million children migrated with their parents from rural areas to cities in mainland China, according to China’s 2010 population census. Parallels exist between these rural-to-urban internal migrant families with young children, nonmigrant natives in urban China, and Chinese immigrants to the United States. For example, many international immigrants and internal migrants experience upward mobility with increases in their socioeconomic status (SES) after moving, which may make their children particularly vulnerable to unhealthy weight gain (Zhou & Cheah, 2015). Moreover, findings on the associations among poverty, childhood food insecurity, and weight status are inconsistent (Fiese, Gundersen, Koester, & Washington, 2011). For example, Casey and colleagues (Casey et al., 2006) reported that children living below the poverty level were significantly more likely to be overweight, if they lived in food insecure households. However, other studies failed to find any significant associations between food insecurity and obesity among children (e.g., Fiese et al., 2011). Also, the economic development of the sending country is an important contributor to immigrant children’s body mass index (BMI; Van Hook & Balistreri, 2007), but how Chinese immigrant families’ SES and mothers’ past food-related experiences are linked with their children’s weight status is unclear.

To unravel the inconsistencies, we took a unique approach to understanding the antecedents of child dietary intake among Chinese immigrants in the United States through a comparison of three Chinese ethnic groups: (1) first-generation international immigrants in the United States, (2) rural-to-urban internal migrants in China, and (3) nonmigrants in urban China. Guided by the ecological risk model of childhood obesity in Chinese immigrant children (Zhou & Cheah, 2015), we explored mother–child characteristics and food-related processes in children’s immediate family environment. Specifically, we examined the unique role of mothers’ early-life food experiences (i.e., food insecurity) in predicting their child’s diet. In addition, we focused on the mediating role of maternal feeding practices in the association between maternal early-life food insecurity (ELFI) and child diet. Finally, the interaction between the child’s own temperament and maternal feeding was examined in relating with child diet.

Maternal Feeding Practices

Within children’s immediate family setting, maternal feeding practices significantly impact children’s health through their intake of specific foods and shaping of their future eating habits (Zhou & Cheah, 2015). Specifically, pressuring the child to eat feeding practices (PEP) refer to mothers’ tendency to pressure their child to consume more food (Birch et al., 2001), or to encourage children’s consumption of specific types of foods (e.g., fruits and vegetables [F&V]). However, such practices are found to be associated with greater food refusal and slower weight loss in children over time (Galloway, Fiorito, Francis, & Birch, 2006).

Chinese parents traditionally use more physical force to control their children’s food intake than European American parents (Zhou, Cheah, Van Hook, & Thompson, Jones, 2015). The Chinese have historically regarded plumpness in children as desirable, and an indicator of health and family wealth (Zhou & Cheah, 2015). Chinese parents also tend to overfeed their children because of exaggerated concerns about insufficient nutrition and energy in their children (Guo et al., 2012). Unfortunately, there has been little empirical examination of PEP and their associations with child diet in Chinese populations in China or the diaspora, and possible predictors of such practices, including mothers’ own experiences with food.

Maternal Early Life Food Insecurity

According to ecological risk model of childhood obesity in Chinese immigrant children (Zhou & Cheah, 2015), maternal characteristics, including their food-related early experiences, can continue to impact food-related interactions later in life. The majority of contemporary Chinese parents with young children were born and raised in the shadow of the Great Chinese Famine, causing tens of millions death. Although the economic reforms of the 1990s rapidly increased income and food security in mainland China, this current generation of Chinese parents grew up in a time and place in which food insecurity and child stunting still posed significant hardships (Xiao & Nie, 2009). Moreover, a gap in food security remains between urban and rural China, and certain regions fall under national food security levels, suffering from poor food access and malnutrition (Xiao & Nie, 2009).

Populations that experience rapid shifts from food insecurity to prosperity are particularly vulnerable to obesity (Kuyper et al., 2006; Kuyper, Smith, & Kaiser, 2009). Mothers who experienced ELFI are more likely to perceive their children as weighing less than ideal and overfeed children, given that both money and food are more available now (Cheah & Van Hook, 2012). Moreover, these mothers also had emotional attachment to and preferences for specific foods, resulting in overfeeding their children such foods (Allen & Wilson, 2005; Olson, Bove, & Miller, 2007). However, whether the associations between ELFI and child diet are mediated by maternal feeding practices have not been examined.

Child Effortful Control

Children’s own temperamental characteristic has been proposed to be a critical correlate of maternal feeding in the ecological risk model of childhood obesity (Zhou & Cheah, 2015). Specifically, children’s temperamental effortful control (EC), defined as their capacity to refrain from a desired behavior, maintain attention on a task, and resist distraction, may be related to their responses to internal satiety cues and important for children’s eating behaviors (Anzman-Frasca, Stifter, & Birch, 2012). Poorer EC may impede the development of self-regulatory eating, and negatively impact children’s ability to suppress their initial responses to and redirect their attention away from desirable food (Tan & Holub, 2011). Overall, children who exhibit higher self-regulatory capacities, such as controlling their impulse for food, are less likely to have excessive weight gain and become obese (Francis & Susman, 2009). Child EC is highly valued in Chinese culture, and particularly relevant for Chinese and Chinese-immigrant children’s socialization (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2009). Nevertheless, rural-to-urban internal migrant Chinese children have been found to have limited opportunity to foster self-regulatory abilities, owing to the low quality of education received and poor interaction and communication with their parents (Hu & Szente, 2010). However, research on how EC may be associated with these children’s physical health is lacking.

In addition, children’s EC may result in parenting practices having varied impact on their diet (Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler, & West, 2000). Children with poorer EC may rely on external cues, and thus be more adversely affected by PEP and susceptible to overeating or unhealthy eating. In contrast, children who regulate their eating well may be more protected from parents’ use of PEP; however, no study has directly tested this interaction. Thus, we examined Chinese children’s EC as a moderator in the association between PEP and children’s dietary intake,

Specific Aims and Hypotheses

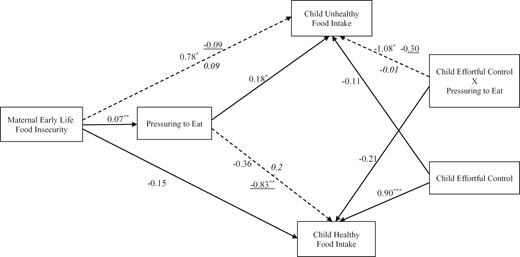

The first overall aim of the present study was to examine and compare group similarities and differences on maternal ELFI and PEP, and child EC and dietary intake (Aim 1). We expected the rural-to-urban internal migrants to have the highest levels of ELFI and PEP, but lowest levels of EC, F&V, and unhealthy foods consumption (Hypothesis 1). Our second overall aim (Aim 2) was to explore and compare the cultural group similarities and differences in the moderated mediation model in three groups of Chinese mothers with young children (Figure 1). Specifically, we aimed to examine the direct effect of maternal ELFI on child dietary intake, the mediating role of maternal PEP in the associations between maternal ELFI and child dietary intake, and the moderating role of child EC in the association between maternal PEP and child dietary intake. We expected that in all groups, maternal ELFI would be associated with greater use of PEP (i.e., direct effect) (Hypothesis 2a). In addition, maternal PEP was expected to be associated with maternal ELFI, and to mediate the association between maternal ELFI and child consumption of more unhealthy foods but less F&V (i.e., indirect effects) (Hypothesis 2b). Finally, children’s EC was expected to serve as a moderator in the association between mothers’ PEP and children’s dietary intake, with maternal PEP expected to have more negative effects on child diet at lower levels of child EC across all three groups (i.e., conditional indirect effects) (Hypothesis 2c).

Final model for mother–child food-related mechanisms predicting child dietary intake within and across three groups of Chinese mothers.

Note. The unstandardized path coefficients and significance levels of the final model are indicated. Solid lines refer to paths with group similarities, and the dashed lines refer to paths with group differences. The regular font, underlined, and italicized path coefficients represent the international immigrant, nonmigrant, and rural-to-urban migrant groups, respectively.

Method

Participants

A total of 817 mothers with preschoolers were recruited across three samples: (1) 119 first-generation international immigrant mothers in a mid-Atlantic U.S. state, with 12% migrating from rural origins and 88% from urban origins; (2) 230 urban nonmigrant mothers, who were born and resided in Shanghai, China; and (3) 468 rural-to-urban internal migrant mothers residing in Shanghai, China, all born in rural China (see Table I for demographic information). All the international immigrant families were middle class in the United States (Hollingshead scores ranged from 40 to 66, M = 60.78, SD = 4.87). In China, both educational and income levels are used to categorize middle-class SES in metropolitan cities, specifically, individuals who (1) received partial college or special training, a standard university degree and/or higher degree(s); and (2) have a household per capita income of >30,000 RMB (4,838 US dollars) per year (Li & Zhang, 2008). Almost all (91.3%) of the urban nonmigrants in our sample were middle class, but the majority of the rural-to-urban internal migrants (83.8%) were lower class.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables of Interest and Analysis of Variance F-Statistics Between Three Groups

| . | M (SD) . | F . | η2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International immigrants (N = 119; 42% girls) . | Urban nonmigrants (N = 230; 49% girls) . | Rural-to-urban internal migrants (N = 468; 42% girls) . | |||

| Maternal age | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | – | |

| Child age | 4.79 (0.93) | 5.09 (0.88) | 5.32 (0.88) | – | |

| Length of residence after migration | 10.98 (4.49) years | N/A | 14.54 (9.86) years | – | |

| Educational level (maternal/paternal) | |||||

| Below partial college | 3.4%/1.7% | 7.9%/7.5% | 79.4%/74.5% | ||

| Partial collage or standard university | 27.1%/12.2% | 78.8%/68.8% | 20.6%/25.1% | ||

| Graduate education | 69.5%/86.1% | 15.3%/23.7% | 0/0.4% | ||

| Household per capita income | |||||

| Below 30,000 RMB | – | 2.7% | 50.8% | ||

| Above 30,000 RMB | – | 97.3% | 49.2% | ||

| Underweight children percentage | 5.4% | 6.1% | 8.3% | ||

| Normal weight children percentage | 72.1% | 70.4% | 68.4% | ||

| Overweight/obese children percentage | 22.5% | 23.5% | 23.3% | – | |

| Early life food insecurity | 0.42 (0.81)b | 0.40 (0.98)c | 1.42 (1.54)b,c | 59.33*** | 0.13 |

| Pressure to eat practice | 3.31 (0.86)a,b | 2.90 (0.92)a,c | 3.66 (0.98)b,c | 51.17*** | 0.11 |

| Effortful control | 4.77 (0.68)b | 4.82 (0.67)c | 4.59 (0.66)b,c | 10.56*** | 0.03 |

| Unhealthy food intake | 2.20 (2.55) | 1.69 (2.06) | 1.84 (1.80) | 2.58 | 0.01 |

| Fruits and vegetables intake | 10.06 (4.94)b | 11.02 (4.40)c | 8.02 (4.53)b,c | 36.23*** | 0.08 |

| . | M (SD) . | F . | η2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International immigrants (N = 119; 42% girls) . | Urban nonmigrants (N = 230; 49% girls) . | Rural-to-urban internal migrants (N = 468; 42% girls) . | |||

| Maternal age | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | – | |

| Child age | 4.79 (0.93) | 5.09 (0.88) | 5.32 (0.88) | – | |

| Length of residence after migration | 10.98 (4.49) years | N/A | 14.54 (9.86) years | – | |

| Educational level (maternal/paternal) | |||||

| Below partial college | 3.4%/1.7% | 7.9%/7.5% | 79.4%/74.5% | ||

| Partial collage or standard university | 27.1%/12.2% | 78.8%/68.8% | 20.6%/25.1% | ||

| Graduate education | 69.5%/86.1% | 15.3%/23.7% | 0/0.4% | ||

| Household per capita income | |||||

| Below 30,000 RMB | – | 2.7% | 50.8% | ||

| Above 30,000 RMB | – | 97.3% | 49.2% | ||

| Underweight children percentage | 5.4% | 6.1% | 8.3% | ||

| Normal weight children percentage | 72.1% | 70.4% | 68.4% | ||

| Overweight/obese children percentage | 22.5% | 23.5% | 23.3% | – | |

| Early life food insecurity | 0.42 (0.81)b | 0.40 (0.98)c | 1.42 (1.54)b,c | 59.33*** | 0.13 |

| Pressure to eat practice | 3.31 (0.86)a,b | 2.90 (0.92)a,c | 3.66 (0.98)b,c | 51.17*** | 0.11 |

| Effortful control | 4.77 (0.68)b | 4.82 (0.67)c | 4.59 (0.66)b,c | 10.56*** | 0.03 |

| Unhealthy food intake | 2.20 (2.55) | 1.69 (2.06) | 1.84 (1.80) | 2.58 | 0.01 |

| Fruits and vegetables intake | 10.06 (4.94)b | 11.02 (4.40)c | 8.02 (4.53)b,c | 36.23*** | 0.08 |

p < .001.

Significant Scheffé post hoc group differences between the international immigrant and the urban nonmigrant Chinese groups.

Significant Scheffé post hoc group differences between the international immigrant and urban nonmigrant Chinese groups.

Significant Scheffé post hoc group differences between the urban nonmigrant and rural-to-urban internal migrant Chinese groups.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables of Interest and Analysis of Variance F-Statistics Between Three Groups

| . | M (SD) . | F . | η2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International immigrants (N = 119; 42% girls) . | Urban nonmigrants (N = 230; 49% girls) . | Rural-to-urban internal migrants (N = 468; 42% girls) . | |||

| Maternal age | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | – | |

| Child age | 4.79 (0.93) | 5.09 (0.88) | 5.32 (0.88) | – | |

| Length of residence after migration | 10.98 (4.49) years | N/A | 14.54 (9.86) years | – | |

| Educational level (maternal/paternal) | |||||

| Below partial college | 3.4%/1.7% | 7.9%/7.5% | 79.4%/74.5% | ||

| Partial collage or standard university | 27.1%/12.2% | 78.8%/68.8% | 20.6%/25.1% | ||

| Graduate education | 69.5%/86.1% | 15.3%/23.7% | 0/0.4% | ||

| Household per capita income | |||||

| Below 30,000 RMB | – | 2.7% | 50.8% | ||

| Above 30,000 RMB | – | 97.3% | 49.2% | ||

| Underweight children percentage | 5.4% | 6.1% | 8.3% | ||

| Normal weight children percentage | 72.1% | 70.4% | 68.4% | ||

| Overweight/obese children percentage | 22.5% | 23.5% | 23.3% | – | |

| Early life food insecurity | 0.42 (0.81)b | 0.40 (0.98)c | 1.42 (1.54)b,c | 59.33*** | 0.13 |

| Pressure to eat practice | 3.31 (0.86)a,b | 2.90 (0.92)a,c | 3.66 (0.98)b,c | 51.17*** | 0.11 |

| Effortful control | 4.77 (0.68)b | 4.82 (0.67)c | 4.59 (0.66)b,c | 10.56*** | 0.03 |

| Unhealthy food intake | 2.20 (2.55) | 1.69 (2.06) | 1.84 (1.80) | 2.58 | 0.01 |

| Fruits and vegetables intake | 10.06 (4.94)b | 11.02 (4.40)c | 8.02 (4.53)b,c | 36.23*** | 0.08 |

| . | M (SD) . | F . | η2 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International immigrants (N = 119; 42% girls) . | Urban nonmigrants (N = 230; 49% girls) . | Rural-to-urban internal migrants (N = 468; 42% girls) . | |||

| Maternal age | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | 38.10 (4.68) | – | |

| Child age | 4.79 (0.93) | 5.09 (0.88) | 5.32 (0.88) | – | |

| Length of residence after migration | 10.98 (4.49) years | N/A | 14.54 (9.86) years | – | |

| Educational level (maternal/paternal) | |||||

| Below partial college | 3.4%/1.7% | 7.9%/7.5% | 79.4%/74.5% | ||

| Partial collage or standard university | 27.1%/12.2% | 78.8%/68.8% | 20.6%/25.1% | ||

| Graduate education | 69.5%/86.1% | 15.3%/23.7% | 0/0.4% | ||

| Household per capita income | |||||

| Below 30,000 RMB | – | 2.7% | 50.8% | ||

| Above 30,000 RMB | – | 97.3% | 49.2% | ||

| Underweight children percentage | 5.4% | 6.1% | 8.3% | ||

| Normal weight children percentage | 72.1% | 70.4% | 68.4% | ||

| Overweight/obese children percentage | 22.5% | 23.5% | 23.3% | – | |

| Early life food insecurity | 0.42 (0.81)b | 0.40 (0.98)c | 1.42 (1.54)b,c | 59.33*** | 0.13 |

| Pressure to eat practice | 3.31 (0.86)a,b | 2.90 (0.92)a,c | 3.66 (0.98)b,c | 51.17*** | 0.11 |

| Effortful control | 4.77 (0.68)b | 4.82 (0.67)c | 4.59 (0.66)b,c | 10.56*** | 0.03 |

| Unhealthy food intake | 2.20 (2.55) | 1.69 (2.06) | 1.84 (1.80) | 2.58 | 0.01 |

| Fruits and vegetables intake | 10.06 (4.94)b | 11.02 (4.40)c | 8.02 (4.53)b,c | 36.23*** | 0.08 |

p < .001.

Significant Scheffé post hoc group differences between the international immigrant and the urban nonmigrant Chinese groups.

Significant Scheffé post hoc group differences between the international immigrant and urban nonmigrant Chinese groups.

Significant Scheffé post hoc group differences between the urban nonmigrant and rural-to-urban internal migrant Chinese groups.

Procedure

Participants in the United States were recruited from preschools, churches, businesses, and community-based organizations. Bilingual research assistants obtained mothers’ consent for their voluntary participation and measured mothers’ and children’s height and weight in their homes. All documents were available in English and Chinese through a multistep translation and backtranslation procedure (Pena, 2007); 97.5% of mothers chose to respond in Chinese. Both groups of participants in Shanghai, a major urban financial center and destination for internal migrants in China, were recruited from four public preschools as well as government-funded preschools for migrant children. Informed consent and questionnaires were sent to children’s home, and collected by teachers. School nurses measured children’s height and weight after being trained by the authors. The study was reviewed and approved by authors’ institutional review boards.

Measures

Child Dietary Intake

Food intake questions were adapted from the federal Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Birth Cohort parent interview (U.S. Department of Education, 2007). Mothers were asked to recall the numbers of times their child consumed various categories of foods during the past 7 days. Mothers responded to, “How many times did your child eat…” followed by the category of food, specific examples, and additional descriptions for clarity using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (1 time per day) to 7 (child did not eat/drink this specific food category in the past 7 days). Unhealthy dietary intake was the score of the average servings of sugar-sweetened beverages, salty snacks, French fries, sweets, and fast foods. Fruits and vegetables (F&V) consumption was obtained by averaging the servings of F&V. Examples of typical Chinese foods obtained through pilot focus groups were included to ensure that the list was culturally appropriate and relevant (e.g., dumplings, stir-fried vegetables, common Chinese snacks like Pocky sticks, and shrimp cracker).

Maternal Early-Life Food Insecurity

We used the six-item subscale of the Household Food Insecurity from the Parental Early-Life Experiences measure (Cheah & Van Hook, 2012), which is a retrospective measure adapted from the six-item scale of current household food insecurity developed by the U.S.D.A. (2008), to assess immigrants’ material and food deprivation when they were about 8 or 9 years old in their country of origin. An index was created to indicate the level of ELFI— (from 0 [no food insecurity] to 6). Sample items include, “My parents worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more” (scale of 1 [often true] to 3 [never true]), and “When you were about 8 or 9, did you ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn’t enough money for food?” (scale of 1 [almost every month] to 4 [no]). Following Cheah and Van Hook (2012), we used a dummy variable indicating the presence of food insecurity for each item (1 = if the participate indicated any level of food insecurity; 0 = otherwise), and then created an index by summing up the dummy variables to obtain the level of food insecurity during childhood. The Cronbach’s α for Household Food Insecurity was 0.81, 0.77, and 0.73 for the international immigrant, urban nonmigrant, and internal migrant Chinese samples, respectively.

Maternal Feeding Practices

The Pressure to Eat subscale of the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ; Birch et al., 2001) was used to measure mothers’ feeding practices that pressured her child to eat. Mothers rated three items (e.g., “If my child says ‘I’m not hungry’, I try to get her to eat anyway.”) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). The CFQ is the most frequently used and validated tool to measure maternal feeding practices, and the pressure to eat subscale has been validated in the Chinese and Chinese-immigrant samples (e.g., Liu, Mallan, Mihrshahi, & Daniels, 2014). The Cronbach’s α for Pressure to Eat was .68, .67, and .63 for the international immigrant, urban nonmigrants, and internal migrant samples, respectively.

Child Effortful Control

The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001), which is widely used and validated for Chinese samples when assessing preschoolers’ temperamental characteristics, was rated by mothers to assess children’s EC (Rothbart et al., 2001). Mothers responded to two scales, Inhibitory Control and Attentional Focusing, on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (extremely untrue) to 7 (extremely true). Inhibitory Control consisted of 10 items assessing children’s ability to regulate their behavior (e.g., “Is usually able to resist temptation when told s/he is not supposed to do something”; α’s = .81, .75, and .72 for international immigrant, urban nonmigrant, and internal migrant groups, respectively). Attentional Focusing consisted of nine items assessing the ability to concentrate on a task when needed (e.g., “Has difficulty leaving a project s/he has begun”; α’s = .72, .71, and .63 for international immigrant, urban nonmigrant, and internal migrant groups, respectively). A composite score for children’s EC was created by averaging the scores of Inhibitory Control and Attention Focusing (Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005). These two scales are the two most theoretically and empirically salient components of EC when using the Rothbart’s CBQ measure (e.g., Posne & Rothbart, 2000; Olson et al., 2005), and were intercorrelated (correlations ranged from .44 to .47, p < .001).

Children’s Height and Weight

Children were measured indoors while wearing light clothing with no shoes or jackets. Children’s height in centimeters was measured using a stadiometer (Charder Medical’s HM200P Height Measuring Rod), and their weight was measured using a digital scale (UC-321 Precision Health Scale by A & D Life Source) by kilograms. The scales arrived from the manufacturer calibrated and cannot be further calibrated. Children’s BMI (or weight/height2) was calculated and used for the analyses.

Analytic Plan

For Aim 1, we examined the descriptive statistics for the variables of interest, and group differences on the variables using the analysis of variance. For Aim 2, the multigroup moderated-mediation model (Figure 1) was tested. The interaction term (i.e., PEP by EC) was created by using the cross-product of the mean-centered pressuring to eat and child EC scores. The full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) method was used to handle missing data and test the model in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Several steps were included to examine the moderated-mediation model in three groups. First, a fully unconstrained model was estimated, in which all the path coefficients were allowed to vary across the three groups. Next, using the fully unconstrained model as a baseline model, multiple group analysis was conducted by sequentially adding equality constraints to the path coefficients to examine whether the model operates in the same way across three groups following the backward search approach. Chi-square difference tests were used to compare the less with more constrained models. A nonsignificant chi-square difference value indicates that the two models provide equal fit to the data, and thus the more constrained/parsimonious model should be retained. A good model fit is indicated by nonsignificant χ2, CFI with minimum of 0.90, with ≥ 0.95 being ideal, RMSEA <0.05, SRMR <0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998). The bootstrapping confidence intervals based on 5,000 random samples were used to test the significance of conditional indirect effects, with confidence intervals not containing zero indicating significant conditional indirect effects (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). The missing data rate was 6.7%, 6.1%, and 1.5% in the international immigrant, urban nonmigrant, and internal migrant samples, respectively. Missing data patterns in three samples were found to be missing completely at random (MCAR) with Little’s MCAR test (Little, 1998): χ2(88, N = 119) = 68.11, p = .94, for the international immigrants; χ2(42, N = 230) = 45.13, p = .34, for the urban nonmigrants; χ2(43, N = 468) = 48.58, p = .258, for the internal migrants. FIML estimation was used to handle missing data in Mplus 7.

Results

Aim 1—Descriptive Analyses

Internal migrant Chinese mothers reported experiencing the highest ELFI, and the lowest F&V intake and EC among the three groups (Table I). Moreover, mothers’ use of PEP was highest in the internal migrant group, followed by the international immigrant group and then the urban nonmigrant group, supporting Hypothesis 1. No group differences were found for children’s unhealthy dietary intake.

Aim 2—Multiple Group Path Analyses

A fully unconstrained model was first estimated in which all the path coefficients were allowed to vary across the three groups. Next, using the fully unconstrained model as a baseline model, a more constrained model after adding equality constraint to one path parameter was compared with the baseline model using chi-square difference tests. The final model achieved good model fit: χ2 (30, N = 846) = 24.87, p = .73, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0, and SRMR = 0.024.

The paths in the final model revealed some group similarities, but the direct, indirect, and conditional indirect effects in the final model differed across the three groups. Maternal ELFI had a direct effect on child unhealthy diet only in the international immigrant group (β = 0.25, p < .01), but no effect on child F&V intake in any group, partially supporting Hypothesis 2a. Maternal ELFI was positively associated with maternal PEP in all three groups (βimmigrant = 0.07, p < .01; βurban = 0.08, p < .01; βmigrant = 0.12, p < .01). Also, maternal PEP was positively correlated with child unhealthy diet in all groups (βimmigrant = 0.06, p < .05; βurban = 0.08, p < .05; βmigrant = 0.12, p < .01), but negatively correlated with child F&V intake in the urban nonmigrant group only (β = −0.18, p < .01). However, the indirect effect of maternal ELFI on child F&V intake through PEP was significant only in the urban nonmigrant group (βurban = −0.04, p < .05), partially supporting Hypothesis 2b.

EC had a direct effect on child F&V intake for all groups (βimmigrant = 0.13, p < .001; βurban = 0.14, p < .001; βmigrant = 0.13, p < .001), but no effect on unhealthy diet in any group. The moderating path from the interaction term to child unhealthy diet was significant for the international immigrant group only, but not significant for the path to child F&V intake, partially supporting Hypothesis 2c. Specifically, for the international immigrant group, PEP was significantly associated with more child unhealthy diet only when the child exhibited low levels of EC. The indirect effects of mothers’ ELFI on children’s unhealthy diet through PEP were conditional on child EC for the international immigrant mothers only.

We further probed this conditional indirect effect by bootstrapping 95% confidence intervals of the unstandardized indirect effects through resampling 5,000 random samples in Mplus 7 at one standard deviation below and above the mean of the moderator (i.e., child EC). The indirect effect was significant only for children with lower levels of EC (θ = 0.91, p < .05, 95% CI [0.27, 2.11]), but not for children with higher levels of EC (θ = −0.55, p = .05, 95% CI [−1.74, 0.09]).

Discussion

Our examination within and across three groups of Chinese mothers revealed important similarities and differences in the factors associated with children’s diet. As expected in Hypothesis 1, low-SES internal migrants in Shanghai face unique challenges in mother–child food-related interactions. These mothers reported having experienced the highest levels of ELFI and engagement in PEP, but their children had the lowest levels of F&V intake and EC, compared with the other two middle-SES groups. Surprisingly, internal migrant children did not differ in their level of unhealthy dietary intake compared with the other groups. Low-income neighborhoods frequently lack full-service grocery stores and farmers’ markets, where residents can buy a variety of high-quality F&V (Larson, Story, & Nelson, 2009). Moreover, when available, healthy foods are more expensive. Thus, ELFI and PEP may be more normative among low-SES internal migrant mothers, and their children are consuming less F&V than their nonmigrant and international immigrant peers in the United States. Internal migrant mothers may pressure their children to eat more (Loth et al., 2013), but possess poorer nutritional knowledge and limited financial abilities to afford healthy foods. Therefore, owing to their lack of nutritional knowledge and limited financial abilities, internal migrant families may instead consume more unhealthy foods (e.g., fast foods, sweets), resulting in similar levels of unhealthy dietary intake compared with the other groups.

Interestingly, the positive association between maternal ELFI and child unhealthy dietary intake was found only in the international immigrant group, partially supporting Hypothesis 2a. Our study provides further evidence that international immigrant mothers’ past food insecurity continues to be associated with their children’s current diet, although they have middle-class status in the United States (Cheah & Van Hook, 2012). Specifically, immigrant mothers’ ELFI experiences seemed to be particularly relevant to their children’s current unhealthy diet, but not through their feeding practices. These mothers are also more likely to encounter unfamiliar foods in the new country (Zhou & Cheah, 2015). When attempting to incorporate typical American foods into their family meals, immigrant mothers may resort to the most accessible types of such foods, which tend to be unhealthy (e.g., hot dogs, pizza, desserts).

We also found that mothers who experienced ELFI used more pressuring to eat strategies in all three groups, partially supporting Hypothesis 2b. Mothers, whose early food-related socialization context composed of food insecurity, material deprivation, and rare instances of obesity, may be less aware of the risks associated with childhood obesity (Kuyper et al., 2009). Chinese mothers tend to use food to display their love toward their children, owing to traditional cultural sanctions against more direct emotional expressions of warmth (Cheah, Li, Zhou, Yamamoto, & Leung, 2015). Mothers with ELFI experiences may value buying foods to express love and satisfy their children, and consider sweets or other snacks, instead of F&V, as treats to express their love toward their children. Thus, mothers’ PEP was found to be associated with unhealthier (but not F&V) intake in children across all groups.

Interestingly, the mediating role of maternal PEP in the negative association between maternal ELFI experiences and child F&V intake, proposed in Hypothesis 2b, was only found in the urban nonmigrant Chinese group. Growing up in China’s biggest city and a global financial center, these Shanghainese mothers may have been more exposed to the dramatic economic growth and Western influences on dietary changes in urban China, compared with the other two groups (Xiao & Nie, 2009). They may have desired but had limited access to processed and Western foods while growing up, and thus had specific emotional attachment to and preferences for these foods instead of F&V (Allen & Wilson, 2005; Olson et al., 2007). Despite their current middle-class status in China, nonmigrant mothers’ ELFI experiences are still associated with their current feeding practices, and may motivate them to buy processed foods and strongly encourage their children to finish their plates (Cheah & Van Hook, 2012).

The mediating role of PEP was further moderated by child EC only in the international immigrant group, partially supporting Hypothesis 2c. Previous developmental research suggested the moderating role of EC in the link between highly controlling parenting and child outcomes (Lengua et al., 2000). Our study added to the previous literature that poorly regulated children were more vulnerable to the adverse effect of their mothers’ ELFI through their use of pressuring to eat practices, resulting in these children’s consumption of more unhealthy foods (Lengua et al., 2000). In contrast, children with high EC skills were better able to regulate their dietary intake on their own, and were thus less affected by their mothers’ use of PEP. Compared with mothers in China, international immigrant mothers have greater exposure to U.S. culture’s valuing of fostering independence in children, and integrate granting autonomy to children into their own parenting (Cheah, Leung, & Zhou, 2013). For instance, Chinese immigrant mothers reported allowing their children control over their own eating (Zhou et al., 2015). Thus, international immigrant mothers might be more responsive to children’s satiety cues when they perceived children to have greater EC ability.

Moreover, across all groups, children’s EC was positively associated with their F&V intake, but not unhealthy diet. This finding further highlights the important role of temperamental characteristics in children’s healthy eating (e.g., Anzman-Frasca et al., 2012). Increasing early self-regulatory abilities may help children foster healthy eating habits and increase consumption of F&V in adulthood. However, our study is the first to suggest that children’s EC is significantly associated with their consumption of more F&V in Chinese and Chinese immigrant families.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the present study need to be noted. First, the cross-sectional design precludes the examination of causal relations between parenting practices, child characteristics, and child dietary intake. Thus, a longitudinal design is needed to establish temporal precedence for the associations between these variables. Second, mother-reported maternal feeding practices and child EC may not accurately reflect actual practices and behaviors, and mothers’ recall of child dietary intake is not as accurate as parents’ consensus recall or observations of children’s dietary intake (Eck, Klesges, & Hanson, 1989). Moreover, additional validation of the child dietary intake and maternal food insecurity measures, as well as explorations of child eating-related regulatory behaviors is needed for future research. Therefore, multiple reporters or observational studies and more rigorous cultural validation of food-related measures is strongly needed for Chinese samples. Third, only middle-SES international immigrant families were included in the cultural comparison, and the heterogeneity in their length of residence in the United States may impact the generalizability of our findings. These middle-SES families were representative of the general larger population of Chinese U.S. immigrants who have been referred to as “hyper-selected” (Lee & Zhou, 2014). As such, we were able to test the long-lasting effects of immigrant mothers’ ELFI despite current middle-class status. However, adding a fourth comparison group of low-SES immigrant families in future studies would illuminate the effects of SES and immigration more clearly. Finally, the current study only considered mother–child food-related interactions, but did not include other potential food-related socialization agents, such as fathers and grandparents. Three-generation childrearing is common among both Chinese immigrant and urban Chinese families (Zhou & Cheah, 2015), and the role of grandparents in preparing and feeding the child in Chinese families should be further explored (Jiang et al., 2007).

Implications and Applications

The present study contributed to our understanding of the risk and protective factors associated with child diet by examining mother–child characteristics and sociocultural contexts across international immigrants, internal migrants, and nonmigrants of the same ethnicity. The comparison of three Chinese groups provided a unique approach to understanding how immigrants’ early-life experiences and their migration contexts may contribute to the risks of child diet for international immigrants and intracountry migrants.

The use of PEP was shown to be a possible mediator through which parents’ past experiences related to children’s eating. If our findings are supported by future longitudinal research, this would suggest maternal feeding as an important venue to prevent or intervene in children’s unhealthy eating. Our findings can be further shared with community organizations and policymakers to inform relevant programs and policies targeting these underserved families. Culturally relevant health education and intervention programs can be tailored to increase at-risk parents’ awareness of their own experiences and the importance of F&V intake and positive parenting practices.

Moreover, our study indicated that greater EC abilities are related to healthier dietary intake among children in China. For international immigrant families, children’s EC was further found to protect children from the adverse impact of mothers’ ELFI through their use of highly controlling parenting. Also, children in the low-SES internal migrant families exhibited the lowest level of child EC and highest levels of maternal PEP, making them particularly vulnerable to the negative impact of contextual risk in the long run. Thus, future intervention and prevention programs should foster children’s self-regulatory abilities and promote more positive maternal feeding practices toward developing healthier food-related family interactions. Taken together, future intervention and prevention efforts should foster more comprehensive family-based programs that can improve children’s healthy eating in the United States and globally.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their valuable time during the course of the research study.

Funding

This study is funded by Foundation for Child Development, NICHD (1R03HD052827-01) to the second author, and National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 31700969) to the first author.

References