-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lexa K Murphy, Kristopher J Preacher, Jason D Rights, Erin M Rodriguez, Heather Bemis, Leandra Desjardins, Kemar Prussien, Adrien M Winning, Cynthia A Gerhardt, Kathryn Vannatta, Bruce E Compas, Maternal Communication in Childhood Cancer: Factor Analysis and Relation to Maternal Distress, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 43, Issue 10, November/December 2018, Pages 1114–1127, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsy054

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study aimed to characterize mothers’ communication with their children in a sample of families with a new or newly relapsed pediatric cancer diagnosis, first using factor analysis and second using structural equation modeling to examine relations between self-reported maternal distress (anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress) and maternal communication in prospective analyses. A hierarchical model of communication was proposed, based on a theoretical framework of warmth and control.

The sample included 115 children (age 5–17 years) with new or newly relapsed cancer (41% leukemia, 18% lymphoma, 6% brain tumor, and 35% other) and their mothers. Mothers reported distress (Beck Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory-II, and Impact of Events Scale-Revised) 2 months after diagnosis (Time 1). Three months later (Time 2), mother–child dyads were video-recorded discussing cancer. Maternal communication was coded with the Iowa Family Interaction Ratings Scales.

Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated poor fit. Exploratory factor analysis suggested a six-factor model (root mean square error of approximation = .04) with one factor reflecting Positive Communication, four factors reflecting Negative Communication (Hostile/Intrusive, Lecturing, Withdrawn, and Inconsistent), and one factor reflecting Expression of Negative Affect. Maternal distress symptoms at Time 1 were all significantly, negatively related to Positive Communication and differentially related to Negative Communication factors at Time 2. Maternal posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms each predicted Expression of Negative Affect.

Findings provide a nuanced understanding of maternal communication in pediatric cancer and identify prospective pathways of risk between maternal distress and communication that can be targeted in intervention.

One of the most difficult tasks facing parents of children with cancer is talking with their child about the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis while simultaneously managing their own distress (Rodriguez et al., 2012). Although family communication has long been proposed as a potential mechanism of both risk and resilience in pediatric psychology (Drotar, 1997), and a recent meta-analysis highlighted the association between family functioning and child adjustment after cancer diagnosis (van Schoors et al., 2017), a comprehensive understanding of the underlying structure and organization of maternal communication in childhood cancer is absent. Parental communication is linked to child distress in several pediatric populations (Holmbeck et al., 2002; Jaser & Grey, 2010; Lim et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2016) and is a modifiable factor that can be targeted in clinical interventions (Wysocki et al., 2008), but greater characterization of communication patterns is needed to inform intervention in pediatric cancer. The purpose of this study is to identify and characterize patterns of observed maternal communication in the context of a child’s cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Previous research about family communication in pediatric psychology has typically been limited to broadly “positive” or “negative” communication styles. However, several comprehensive communication models have characterized family communication as having multiple dimensions that provide greater nuance; these models have anchors in flexibility and cohesion (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2013) and warmth/hostility and autonomy/control (Beveridge & Berg, 2007). Across these models, there are common themes that evoke dimensions of warmth and control that have origins in Baumrind’s (1968) authoritative parenting style, which encompasses both warmth and support, as well as developmentally appropriate control, structure, and boundaries. In families undergoing stress, including the stress of caring for a child with a chronic health condition, mean levels of negative communication patterns may increase (for review, see Murphy, Murray, & Compas, 2017), and families may spend more time focusing on emotional content to process specific negative events (see Fivush, 2007), but the structure of communication itself is not expected to change.

A recent review of direct observation of family communication in pediatric populations (Murphy et al., 2017) proposed a unifying model of communication that is hierarchical and similarly emphasizes warmth and control. This hierarchical model includes more specific categories of communication beyond “positive” or “negative.” It describes two patterns representing specific forms of positive communication: warm (positive affect, affection, and support) and structured (positive reinforcement, consistency, and guidance) communication. The model also describes two patterns representing specific forms of negative communication: hostile/intrusive (high levels of structure with a lack of warmth) and withdrawn (low levels of both warmth and structure) communication. This model has been applied to previous pediatric studies that have largely measured family communication by studying mother–child dyads (Murphy et al., 2017). It is expected that this model of family communication may also apply to maternal communication after child cancer diagnosis.

In the current study, the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001) was used to measure maternal communication during mother–child conversations about the child’s cancer. The IFIRS was originally developed as a macro-level coding system to examine family communication across a variety of settings and was first used with families in the American Midwest (Melby & Conger, 2001). It can flexibly be applied to a range of family members (e.g., dyadic pairs or larger families), ages, and discussion topics (e.g., a cancer-specific discussion). It also has detailed anchors of behavior and entails rigorous coding procedures (Melby & Conger, 2001). The IFIRS is commonly used in clinical and developmental psychology studies, has been validated in families of diverse racial backgrounds (Frabutt et al., 2002; Kim & Ge, 2000), and is used to examine mediators of family-based interventions (Compas et al., 2010). The IFIRS was also evaluated in a review of evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology and met “well-established” criteria (i.e., presented in at least two peer-reviewed journals by different research teams, detailed to allow for evaluation and replication, and good reliability and validity; Alderfer et al., 2008). Family communication has been coded with the IFIRS in a variety of pediatric samples including diabetes (Jaser & Grey, 2010), Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI; Raj et al., 2014), cystic fibrosis (DeLambo et al., 2004), and asthma (Lim et al., 2008). Importantly, the IFIRS is the only macro-level rating scale that has been validated in a pediatric cancer sample (Dunn et al., 2011). Given that the goal of the current study was to broadly characterize maternal communication, the IFIRS is an excellent fit, as it yields codes that capture a wide range of verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors.

Previous studies using the IFIRS in pediatric samples have either focused on individual codes of interest or composites (linear combinations created by averaging individual codes), typically labeled positive or negative communication (Lim et al., 2008; Rodriguez et al., 2013). Examining individual codes or composites can help address a specific theoretical question of interest, but this approach does not characterize the overall structure of communication. These approaches are also limited, as composites vary from study to study based on researchers’ individual approaches, and composites combine sources of error specific to individual items. In contrast, factor analytic methods attempt to explain correlations among a large number of measured variables by yielding a smaller number of distinct latent variables that are free of item-specific measurement error (Brown, 2015). When applied to direct observation coding systems, factor analysis can yield a parsimonious and clinically useful model of communication behaviors by identifying distinct communication variables and specifying correlations among them.

Despite the potential benefits, relatively few previous studies have applied factor analytic methods to observational systems of family communication. Those studies that have, typically employ data-driven, exploratory factor analytic techniques or principal component analyses. For example, two previous studies conducted exploratory factor analyses of the IFIRS: one used husband–wife discussions about conflict and support (Williamson, Bradbury, Trail, & Karney, 2011) and the other examined maternal communication with adolescents (age 12–17 years) with TBI (Raj et al., 2014). Although the individual codes used varied between studies, both identified three-factor models that included Positivity/Warmth (e.g., Positive Mood code), Negativity (e.g., Hostility code), and Effectiveness (e.g., Communication code). These approaches were used for the purposes of data reduction, rather than to characterize the organization of communication. In such cases where there are firm a priori hypotheses about the structure of communication, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) approach is considered appropriate (Brown, 2015). Therefore, a theory-driven confirmatory approach could build on these previous findings in the IFIRS system to better characterize communication in the current sample.

Although the underlying structure of maternal communication in childhood cancer has not yet been fully investigated, previous theory and research reviewed above are sufficient to make specific hypotheses about the structure. It is expected that IFIRS codes of mothers’ communication may be organized around a framework of warmth and control, with Warm and Structured representing specific aspects of Positive Communication and Hostile/Intrusive and Withdrawn as specific aspects of Negative Communication (Murphy et al., 2017). Because IFIRS codes also tap expression of negative affect (anxiety and sadness), these codes may represent a distinct factor, clustering separately from communication codes.

To further characterize maternal communication in pediatric cancer, an initial test of the correlates of these factors was conducted by examining the prospective relationship between maternal distress near the time of new or newly relapsed cancer diagnosis and communication 3 months later. Distress was measured before communication to provide a more stringent test of the association between these constructs and to allow for more time to pass after the child’s diagnosis before asking families to be video-recorded discussing cancer diagnosis and treatment. These analyses have clinical relevance, as a portion of this population is at heightened risk for maternal and child distress after cancer diagnosis (Pai et al., 2007; Pinquart & Shen, 2011). Previous research across pediatric populations has indicated that maternal distress and communication are related such that increased rates of distress are related to higher levels of negative communication patterns and lower levels of positive communication patterns (Celano et al., 2008; Lim, Wood, & Miller, 2008). However, the analyses in this study extend previous research by examining prospective relations between distress and communication, using latent variables of communication patterns, and examining differential relations among specific symptom clusters (i.e., anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress symptoms [PTSS]).

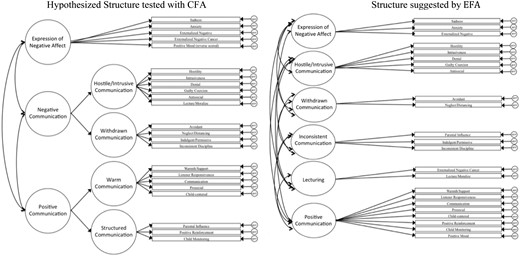

The primary aim of this study was to characterize the latent structure of maternal communication during mother–child discussions of the child’s cancer, as measured by the IFIRS. Given previous theory and research in pediatric populations, CFA was used to test a hierarchical model of maternal communication, with Warm and Structured representing components of Positive Communication and Hostile/Intrusive and Withdrawn representing components of Negative Communication (see Figure 1). An initial test of the identified factor structure was also conducted by examining correlations between latent communication variables and maternal distress in prospective analyses. Contingent on the factor structure of maternal communication, it was expected that self-reported maternal anxiety, depression, and PTSS near the time of the child’s diagnosis would predict less Positive Communication (Warm and Structured), greater Negative Communication (Hostile/Intrusive and Withdrawn), and greater Expression of Negative Affect as observed during mother–child conversations 3 months later.

Factor structure of maternal communication in pediatric cancer with IFIRS codes.

Note. The figure on the left represents the proposed factor structure tested in CFA (endogenous latent variable disturbances excluded for simplicity of visualization). The figure on the right represents the structure suggested by EFA (showing each item loading onto the single latent variable for which it had the largest factor loading).

CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; EFA = exploratory factor analysis.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current study included 115 children with cancer and their mothers. Children ranged from 5 to 17 years old (M = 10.32, SD = 3.86), and 48% (N = 55) were female, 80% were Caucasian, 12% were African-American, 1% were American Indian, 7% reported “other” for their race, and 7% were Hispanic/Latino. Cancer diagnoses included leukemia (41%), lymphoma (18%), brain tumor (6%), and other solid tumors (35%). One hundred nine (95%) were recruited after initial diagnosis and 6 after a relapse. Mothers were on average 37.94 years old (SD = 7.78) and came from a range of educational backgrounds (high school level to 4-year graduate school; Mdn = 3 years of college) as well as family income levels (27% $25,000 or less; 27% $25,001–50,000; 14% $50,001–75,000; 11% $75,001–100,000; 21% $100,001 or above).

Procedure

This study was part of a larger study examining family adjustment to pediatric cancer (Compas et al., 2014). Families were recruited from two pediatric oncology centers in the Southeastern and Midwestern U.S. Eligibility criteria included (a) children 5–17 years of age, (b) at least 1 week post new or newly relapsed cancer diagnosis at recruitment, (c) receiving treatment through the oncology division at the pediatric centers, and (d) no preexisting developmental disability. Informed consent/assent was obtained from parents and children, and families were compensated for their participation. Of the 385 families who were eligible for participation, 335 (87%) had a family member agree to participate. Per our Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol, we were unable to systematically track reasons for declining, but anecdotal reports suggested that if families did offer a reason, the most common was lack of time because of the burdens of medical treatment or lack of interest. At Time 1 (T1), 2 months after the child’s initial cancer diagnosis or relapse, parents reported on family demographic characteristics and symptoms of distress (anxiety, depression, and PTSS).

Families who completed questionnaires at T1 were then approached 3 months later at Time 2 (T2) to participate in a videotaped parent–child observation task. There was a separate IRB protocol and consent process at this time point so as not to put undue pressure at T1 on families who did not want to be videotaped. Eligibility criteria for approach at this time point included (1) the child had not passed away and was not in hospice care, (2) a parent completed questionnaires at T1, and (3) < 3 months had passed since T1.

Of the 335 families who participated in the initial study at T1, 239 were eligible for the observation study (i.e., 77 families were not recruited because they participated before the observational study began, and 19 families were not recruited because the child had passed or was receiving hospice care). Of the 239 families who were eligible, 120 (50%) of families completed the videotaped observation task. Common reasons offered for declining at this time point included lack of time because of treatment, not wanting to be videotaped, and lack of interest. Families who completed the interaction task did not significantly differ from families who declined on maternal distress symptoms, child age, gender, race, ethnicity, or cancer diagnosis (p >.10). Because of the small number of fathers who participated in the observation (N = 23), they were excluded from present analyses. This left 115 mother–child dyads who completed the task. Of these, one mother did not complete the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and two mothers did not complete the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R). To use participants with partial data, all analyses were conducted using full information maximum likelihood (FIML; see Data Analyses below).

During the task, mother–child dyads first completed a 5-min puzzle task as a warm up, and then they were asked to have a conversation about the child’s cancer in whatever way felt natural to them. The task lasted 15 min and has been validated with a pediatric cancer sample (Dunn et al., 2011). Mothers received a card with prompts (originally derived from focus groups with families of children with pediatric cancer diagnoses) to help guide the conversation as needed (“What have we each learned about cancer and how it is treated?” “What parts of your cancer and its treatment have been the hardest for each of us?” “What kinds of feelings or emotions have we each had since we found out you have cancer?” “What are the ways we each try to deal with these feelings and emotions?” “What is it about cancer that has most affected each of our lives?” “How do we each feel about what might happen in the next year and after that?” “If we were writing a book about cancer for other children and parents, what would we each include?”).

Measures

Maternal Communication

The IFIRS is used to code mothers’ verbal and nonverbal communication, behaviors, and emotions in a videotaped interaction (Melby & Conger, 2001). Codes are assigned values from 1 (absence of the behavior or emotion) to 9 (the behavior or emotion is “mainly characteristic” of the mother during the interaction). IFIRS may be considered quasi-interval and therefore suitable for factor analysis with maximum likelihood (ML) procedures (Floyd & Widaman, 1995). Table I presents code definitions and examples. All observations were double-coded independently by two coders at one research site. Mean reliability between coders (intraclass correlation coefficients [ICC]) was α = .68. All coders first passed a written test of code definitions and examples and were trained to 80% reliability by expert raters. Per the IFIRS manual, when coders’ ratings differed by one point, the higher rating was used; when ratings differed by two or more points coders reached agreement through discussion.

| Code . | M (SD) . | Range . | Definition . | Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warmth/Support | 5.72 (1.59) | 2–9 | Expressions of care, concern, support, or encouragement toward the child | “You were really brave” |

| Hugs; thumbs up | ||||

| Listener Responsiveness | 6.70 (1.06) | 3–9 | The mother’s nonverbal and verbal responsiveness as a listener to the verbalizations of the child through behaviors that validate and indicate attentiveness to the child | “Wow!”; “I like your idea” |

| Nods, eye contact while the child is speaking | ||||

| Prosocial | 6.51 (1.05) | 3–8 | Demonstrations of helpfulness, sensitivity, cooperation, sympathy, and respectfulness toward the child in an age-appropriate manner. Reflects a level of maturity appropriate to one’s age | “I’m sorry, I didn’t know that bothered you” |

| Taking turns, self-controlled | ||||

| Child-Centered | 6.31 (1.30) | 2–9 | Mother’s responses to child are appropriate and based on child’s behavior and speech; they offer the right mix of support and independence, so child can experience mastery, success, pride, and develop effective self-regulatory skills | “You’ve almost got it!” |

| Acknowledges child’s affect; sharing positive affect | ||||

| Parental Influence | 3.67 (1.63) | 1–7 | The mother’s direct and indirect attempts to influence, regulate, or control the child’s life according to commonly accepted, age-appropriate standards | “We always clean up after we play” |

| Requires child to pay attention; confronts child when misbehaves | ||||

| Positive Reinforcement | 2.62 (1.45) | 1–6 | The extent to which the mother responds positively to the child’s “appropriate” behavior or behavior that meets specific maternal standards | “You are so good at this” |

| Praise; smiles | ||||

| Child Monitoring | 6.03 (1.34) | 2–9 | The extent of the mother’s specific knowledge and information concerning the child’s life and daily activities. Indicates the extent to which the mother accurately tracks the behaviors, activities, and social involvements of the child | “You’re really good at puzzles” |

| Asking specific questions; tracks child closely during task | ||||

| Communication | 7.11 (.89) | 4–9 | The mother’s ability to neutrally or positively express her own point of view, needs, wants, etc., in a clear, appropriate, and reasonable manner and to demonstrate consideration of the child’s point of view. The good communicator promotes rather than inhibits exchange of information | “This is really important to me because…” |

| Clarifies other’s position | ||||

| Positive Mood | 5.67 (1.21) | 2–8 | Expressions of contentment, happiness, and optimism toward self, others, or things in general | “We can do this!” |

| Laughing; animated gestures | ||||

| Hostility | 2.58 (1.54) | 1–8 | The extent to which hostile, angry, critical, disapproving, rejecting, or contemptuous behavior is directed toward the child’s behavior (actions), appearance, or personal characteristics | “You always do it wrong” |

| Mocking; criticism | ||||

| Intrusiveness | 3.22 (1.63) | 1–8 | The extent to which the mother is domineering and overcontrolling in interactions with their child; mother’s behavior is adult-centered rather than child-centered | “I think you should put away all the lego pieces first then the puzzle pieces” |

| Interrupting; not allowing child to make choices | ||||

| Denial | 1.35 (.67) | 1–4 | Active rejection of the existence of or personal responsibility for a past or present situation for which one is responsible or shares responsibility | “It’s not my fault” |

| Blaming the child; changing the subject | ||||

| Guilty Coercion | 1.31 (.75) | 1–5 | Achieving goals or attempts to control or change the behavior of the child by crying, whining, manipulation, or revealing needs or wants in a whiny or whiny-blaming manner | “Look at all I’ve done for you and you don’t even appreciate it” |

| Whining; sighing | ||||

| Lecture/Moralize | 3.27 (1.84) | 1–8 | Telling the child how to think, feel, etc., in a way that assumes the mother is the expert and/or has superior wisdom; at high levels may provide little opportunity for the child to respond, initiate, or think independently | “You should know better” |

| Platitudes; chiding | ||||

| Antisocial | 2.66 (1.37) | 1–7 | Demonstrations of self-centered, egocentric, acting out, and out-of-control behavior that shows defiance, active resistance, insensitivity toward others, or lack of constraint. Reflects immaturity and age-inappropriate behaviors | “You can’t answer again. It’s my turn!” |

| Complaining | ||||

| Avoidant | 2.11 (1.13) | 1–5 | The extent to which the mother physically orients herself away from the child in such a manner as to avoid interaction | Looks down or away after child speaks |

| Recoiling; detached | ||||

| Neglecting/Distancing | 2.53 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother minimizes the amount of time, contact, or effort she expends on the child; ignoring or psychological/physical distancing in the interaction situation | “Take care of it yourself” |

| Sitting passively while child completes task; pushing child away | ||||

| Indulgent/Permissive | 1.76 (1.36) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother is excessively lenient and tolerant of the child’s misbehavior or has given up attempts to control the child; a laissez faire or a defeated attitude by the mother regarding the child’s behavior | “Do what you want, you don’t listen to me anyway” |

| Few attempts to get child to comply with task; acting more like a peer than a parent | ||||

| Inconsistent Discipline | 1.82 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree of maternal inconsistency and lack of follow through in maintaining and adhering to the rules and standards of conduct for the child’s behavior | “I just couldn’t see grounding you for the whole month, so I let you out of your punishment” |

| Idle threats; giving up on instructions | ||||

| Sadness | 4.97 (1.44) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as despondence, unhappiness, sadness, depression, and regret | “I feel stuck here forever” |

| Crying; listless; head in hands | ||||

| Anxiety | 4.60 (1.58) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as nervousness, fear, tension, stress, worry, and concern | “I’m really worried” |

| Fidgeting; tense, rigid body movements | ||||

| Externalized Negative | 3.62 (1.65) | 1–7 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding people, events, or things outside the immediate setting | “Those two are really troublemakers” |

| Complaints; impatience | ||||

| Externalized Negative—Cancer | 2.91 (1.70) | 1–8 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding cancer treatment and its effects | “I hate chemo” |

| Complaints; impatience |

| Code . | M (SD) . | Range . | Definition . | Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warmth/Support | 5.72 (1.59) | 2–9 | Expressions of care, concern, support, or encouragement toward the child | “You were really brave” |

| Hugs; thumbs up | ||||

| Listener Responsiveness | 6.70 (1.06) | 3–9 | The mother’s nonverbal and verbal responsiveness as a listener to the verbalizations of the child through behaviors that validate and indicate attentiveness to the child | “Wow!”; “I like your idea” |

| Nods, eye contact while the child is speaking | ||||

| Prosocial | 6.51 (1.05) | 3–8 | Demonstrations of helpfulness, sensitivity, cooperation, sympathy, and respectfulness toward the child in an age-appropriate manner. Reflects a level of maturity appropriate to one’s age | “I’m sorry, I didn’t know that bothered you” |

| Taking turns, self-controlled | ||||

| Child-Centered | 6.31 (1.30) | 2–9 | Mother’s responses to child are appropriate and based on child’s behavior and speech; they offer the right mix of support and independence, so child can experience mastery, success, pride, and develop effective self-regulatory skills | “You’ve almost got it!” |

| Acknowledges child’s affect; sharing positive affect | ||||

| Parental Influence | 3.67 (1.63) | 1–7 | The mother’s direct and indirect attempts to influence, regulate, or control the child’s life according to commonly accepted, age-appropriate standards | “We always clean up after we play” |

| Requires child to pay attention; confronts child when misbehaves | ||||

| Positive Reinforcement | 2.62 (1.45) | 1–6 | The extent to which the mother responds positively to the child’s “appropriate” behavior or behavior that meets specific maternal standards | “You are so good at this” |

| Praise; smiles | ||||

| Child Monitoring | 6.03 (1.34) | 2–9 | The extent of the mother’s specific knowledge and information concerning the child’s life and daily activities. Indicates the extent to which the mother accurately tracks the behaviors, activities, and social involvements of the child | “You’re really good at puzzles” |

| Asking specific questions; tracks child closely during task | ||||

| Communication | 7.11 (.89) | 4–9 | The mother’s ability to neutrally or positively express her own point of view, needs, wants, etc., in a clear, appropriate, and reasonable manner and to demonstrate consideration of the child’s point of view. The good communicator promotes rather than inhibits exchange of information | “This is really important to me because…” |

| Clarifies other’s position | ||||

| Positive Mood | 5.67 (1.21) | 2–8 | Expressions of contentment, happiness, and optimism toward self, others, or things in general | “We can do this!” |

| Laughing; animated gestures | ||||

| Hostility | 2.58 (1.54) | 1–8 | The extent to which hostile, angry, critical, disapproving, rejecting, or contemptuous behavior is directed toward the child’s behavior (actions), appearance, or personal characteristics | “You always do it wrong” |

| Mocking; criticism | ||||

| Intrusiveness | 3.22 (1.63) | 1–8 | The extent to which the mother is domineering and overcontrolling in interactions with their child; mother’s behavior is adult-centered rather than child-centered | “I think you should put away all the lego pieces first then the puzzle pieces” |

| Interrupting; not allowing child to make choices | ||||

| Denial | 1.35 (.67) | 1–4 | Active rejection of the existence of or personal responsibility for a past or present situation for which one is responsible or shares responsibility | “It’s not my fault” |

| Blaming the child; changing the subject | ||||

| Guilty Coercion | 1.31 (.75) | 1–5 | Achieving goals or attempts to control or change the behavior of the child by crying, whining, manipulation, or revealing needs or wants in a whiny or whiny-blaming manner | “Look at all I’ve done for you and you don’t even appreciate it” |

| Whining; sighing | ||||

| Lecture/Moralize | 3.27 (1.84) | 1–8 | Telling the child how to think, feel, etc., in a way that assumes the mother is the expert and/or has superior wisdom; at high levels may provide little opportunity for the child to respond, initiate, or think independently | “You should know better” |

| Platitudes; chiding | ||||

| Antisocial | 2.66 (1.37) | 1–7 | Demonstrations of self-centered, egocentric, acting out, and out-of-control behavior that shows defiance, active resistance, insensitivity toward others, or lack of constraint. Reflects immaturity and age-inappropriate behaviors | “You can’t answer again. It’s my turn!” |

| Complaining | ||||

| Avoidant | 2.11 (1.13) | 1–5 | The extent to which the mother physically orients herself away from the child in such a manner as to avoid interaction | Looks down or away after child speaks |

| Recoiling; detached | ||||

| Neglecting/Distancing | 2.53 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother minimizes the amount of time, contact, or effort she expends on the child; ignoring or psychological/physical distancing in the interaction situation | “Take care of it yourself” |

| Sitting passively while child completes task; pushing child away | ||||

| Indulgent/Permissive | 1.76 (1.36) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother is excessively lenient and tolerant of the child’s misbehavior or has given up attempts to control the child; a laissez faire or a defeated attitude by the mother regarding the child’s behavior | “Do what you want, you don’t listen to me anyway” |

| Few attempts to get child to comply with task; acting more like a peer than a parent | ||||

| Inconsistent Discipline | 1.82 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree of maternal inconsistency and lack of follow through in maintaining and adhering to the rules and standards of conduct for the child’s behavior | “I just couldn’t see grounding you for the whole month, so I let you out of your punishment” |

| Idle threats; giving up on instructions | ||||

| Sadness | 4.97 (1.44) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as despondence, unhappiness, sadness, depression, and regret | “I feel stuck here forever” |

| Crying; listless; head in hands | ||||

| Anxiety | 4.60 (1.58) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as nervousness, fear, tension, stress, worry, and concern | “I’m really worried” |

| Fidgeting; tense, rigid body movements | ||||

| Externalized Negative | 3.62 (1.65) | 1–7 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding people, events, or things outside the immediate setting | “Those two are really troublemakers” |

| Complaints; impatience | ||||

| Externalized Negative—Cancer | 2.91 (1.70) | 1–8 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding cancer treatment and its effects | “I hate chemo” |

| Complaints; impatience |

Note. IFIRS = Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales; Range 1 (absence) to 9 (mainly characteristic).

| Code . | M (SD) . | Range . | Definition . | Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warmth/Support | 5.72 (1.59) | 2–9 | Expressions of care, concern, support, or encouragement toward the child | “You were really brave” |

| Hugs; thumbs up | ||||

| Listener Responsiveness | 6.70 (1.06) | 3–9 | The mother’s nonverbal and verbal responsiveness as a listener to the verbalizations of the child through behaviors that validate and indicate attentiveness to the child | “Wow!”; “I like your idea” |

| Nods, eye contact while the child is speaking | ||||

| Prosocial | 6.51 (1.05) | 3–8 | Demonstrations of helpfulness, sensitivity, cooperation, sympathy, and respectfulness toward the child in an age-appropriate manner. Reflects a level of maturity appropriate to one’s age | “I’m sorry, I didn’t know that bothered you” |

| Taking turns, self-controlled | ||||

| Child-Centered | 6.31 (1.30) | 2–9 | Mother’s responses to child are appropriate and based on child’s behavior and speech; they offer the right mix of support and independence, so child can experience mastery, success, pride, and develop effective self-regulatory skills | “You’ve almost got it!” |

| Acknowledges child’s affect; sharing positive affect | ||||

| Parental Influence | 3.67 (1.63) | 1–7 | The mother’s direct and indirect attempts to influence, regulate, or control the child’s life according to commonly accepted, age-appropriate standards | “We always clean up after we play” |

| Requires child to pay attention; confronts child when misbehaves | ||||

| Positive Reinforcement | 2.62 (1.45) | 1–6 | The extent to which the mother responds positively to the child’s “appropriate” behavior or behavior that meets specific maternal standards | “You are so good at this” |

| Praise; smiles | ||||

| Child Monitoring | 6.03 (1.34) | 2–9 | The extent of the mother’s specific knowledge and information concerning the child’s life and daily activities. Indicates the extent to which the mother accurately tracks the behaviors, activities, and social involvements of the child | “You’re really good at puzzles” |

| Asking specific questions; tracks child closely during task | ||||

| Communication | 7.11 (.89) | 4–9 | The mother’s ability to neutrally or positively express her own point of view, needs, wants, etc., in a clear, appropriate, and reasonable manner and to demonstrate consideration of the child’s point of view. The good communicator promotes rather than inhibits exchange of information | “This is really important to me because…” |

| Clarifies other’s position | ||||

| Positive Mood | 5.67 (1.21) | 2–8 | Expressions of contentment, happiness, and optimism toward self, others, or things in general | “We can do this!” |

| Laughing; animated gestures | ||||

| Hostility | 2.58 (1.54) | 1–8 | The extent to which hostile, angry, critical, disapproving, rejecting, or contemptuous behavior is directed toward the child’s behavior (actions), appearance, or personal characteristics | “You always do it wrong” |

| Mocking; criticism | ||||

| Intrusiveness | 3.22 (1.63) | 1–8 | The extent to which the mother is domineering and overcontrolling in interactions with their child; mother’s behavior is adult-centered rather than child-centered | “I think you should put away all the lego pieces first then the puzzle pieces” |

| Interrupting; not allowing child to make choices | ||||

| Denial | 1.35 (.67) | 1–4 | Active rejection of the existence of or personal responsibility for a past or present situation for which one is responsible or shares responsibility | “It’s not my fault” |

| Blaming the child; changing the subject | ||||

| Guilty Coercion | 1.31 (.75) | 1–5 | Achieving goals or attempts to control or change the behavior of the child by crying, whining, manipulation, or revealing needs or wants in a whiny or whiny-blaming manner | “Look at all I’ve done for you and you don’t even appreciate it” |

| Whining; sighing | ||||

| Lecture/Moralize | 3.27 (1.84) | 1–8 | Telling the child how to think, feel, etc., in a way that assumes the mother is the expert and/or has superior wisdom; at high levels may provide little opportunity for the child to respond, initiate, or think independently | “You should know better” |

| Platitudes; chiding | ||||

| Antisocial | 2.66 (1.37) | 1–7 | Demonstrations of self-centered, egocentric, acting out, and out-of-control behavior that shows defiance, active resistance, insensitivity toward others, or lack of constraint. Reflects immaturity and age-inappropriate behaviors | “You can’t answer again. It’s my turn!” |

| Complaining | ||||

| Avoidant | 2.11 (1.13) | 1–5 | The extent to which the mother physically orients herself away from the child in such a manner as to avoid interaction | Looks down or away after child speaks |

| Recoiling; detached | ||||

| Neglecting/Distancing | 2.53 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother minimizes the amount of time, contact, or effort she expends on the child; ignoring or psychological/physical distancing in the interaction situation | “Take care of it yourself” |

| Sitting passively while child completes task; pushing child away | ||||

| Indulgent/Permissive | 1.76 (1.36) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother is excessively lenient and tolerant of the child’s misbehavior or has given up attempts to control the child; a laissez faire or a defeated attitude by the mother regarding the child’s behavior | “Do what you want, you don’t listen to me anyway” |

| Few attempts to get child to comply with task; acting more like a peer than a parent | ||||

| Inconsistent Discipline | 1.82 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree of maternal inconsistency and lack of follow through in maintaining and adhering to the rules and standards of conduct for the child’s behavior | “I just couldn’t see grounding you for the whole month, so I let you out of your punishment” |

| Idle threats; giving up on instructions | ||||

| Sadness | 4.97 (1.44) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as despondence, unhappiness, sadness, depression, and regret | “I feel stuck here forever” |

| Crying; listless; head in hands | ||||

| Anxiety | 4.60 (1.58) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as nervousness, fear, tension, stress, worry, and concern | “I’m really worried” |

| Fidgeting; tense, rigid body movements | ||||

| Externalized Negative | 3.62 (1.65) | 1–7 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding people, events, or things outside the immediate setting | “Those two are really troublemakers” |

| Complaints; impatience | ||||

| Externalized Negative—Cancer | 2.91 (1.70) | 1–8 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding cancer treatment and its effects | “I hate chemo” |

| Complaints; impatience |

| Code . | M (SD) . | Range . | Definition . | Examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warmth/Support | 5.72 (1.59) | 2–9 | Expressions of care, concern, support, or encouragement toward the child | “You were really brave” |

| Hugs; thumbs up | ||||

| Listener Responsiveness | 6.70 (1.06) | 3–9 | The mother’s nonverbal and verbal responsiveness as a listener to the verbalizations of the child through behaviors that validate and indicate attentiveness to the child | “Wow!”; “I like your idea” |

| Nods, eye contact while the child is speaking | ||||

| Prosocial | 6.51 (1.05) | 3–8 | Demonstrations of helpfulness, sensitivity, cooperation, sympathy, and respectfulness toward the child in an age-appropriate manner. Reflects a level of maturity appropriate to one’s age | “I’m sorry, I didn’t know that bothered you” |

| Taking turns, self-controlled | ||||

| Child-Centered | 6.31 (1.30) | 2–9 | Mother’s responses to child are appropriate and based on child’s behavior and speech; they offer the right mix of support and independence, so child can experience mastery, success, pride, and develop effective self-regulatory skills | “You’ve almost got it!” |

| Acknowledges child’s affect; sharing positive affect | ||||

| Parental Influence | 3.67 (1.63) | 1–7 | The mother’s direct and indirect attempts to influence, regulate, or control the child’s life according to commonly accepted, age-appropriate standards | “We always clean up after we play” |

| Requires child to pay attention; confronts child when misbehaves | ||||

| Positive Reinforcement | 2.62 (1.45) | 1–6 | The extent to which the mother responds positively to the child’s “appropriate” behavior or behavior that meets specific maternal standards | “You are so good at this” |

| Praise; smiles | ||||

| Child Monitoring | 6.03 (1.34) | 2–9 | The extent of the mother’s specific knowledge and information concerning the child’s life and daily activities. Indicates the extent to which the mother accurately tracks the behaviors, activities, and social involvements of the child | “You’re really good at puzzles” |

| Asking specific questions; tracks child closely during task | ||||

| Communication | 7.11 (.89) | 4–9 | The mother’s ability to neutrally or positively express her own point of view, needs, wants, etc., in a clear, appropriate, and reasonable manner and to demonstrate consideration of the child’s point of view. The good communicator promotes rather than inhibits exchange of information | “This is really important to me because…” |

| Clarifies other’s position | ||||

| Positive Mood | 5.67 (1.21) | 2–8 | Expressions of contentment, happiness, and optimism toward self, others, or things in general | “We can do this!” |

| Laughing; animated gestures | ||||

| Hostility | 2.58 (1.54) | 1–8 | The extent to which hostile, angry, critical, disapproving, rejecting, or contemptuous behavior is directed toward the child’s behavior (actions), appearance, or personal characteristics | “You always do it wrong” |

| Mocking; criticism | ||||

| Intrusiveness | 3.22 (1.63) | 1–8 | The extent to which the mother is domineering and overcontrolling in interactions with their child; mother’s behavior is adult-centered rather than child-centered | “I think you should put away all the lego pieces first then the puzzle pieces” |

| Interrupting; not allowing child to make choices | ||||

| Denial | 1.35 (.67) | 1–4 | Active rejection of the existence of or personal responsibility for a past or present situation for which one is responsible or shares responsibility | “It’s not my fault” |

| Blaming the child; changing the subject | ||||

| Guilty Coercion | 1.31 (.75) | 1–5 | Achieving goals or attempts to control or change the behavior of the child by crying, whining, manipulation, or revealing needs or wants in a whiny or whiny-blaming manner | “Look at all I’ve done for you and you don’t even appreciate it” |

| Whining; sighing | ||||

| Lecture/Moralize | 3.27 (1.84) | 1–8 | Telling the child how to think, feel, etc., in a way that assumes the mother is the expert and/or has superior wisdom; at high levels may provide little opportunity for the child to respond, initiate, or think independently | “You should know better” |

| Platitudes; chiding | ||||

| Antisocial | 2.66 (1.37) | 1–7 | Demonstrations of self-centered, egocentric, acting out, and out-of-control behavior that shows defiance, active resistance, insensitivity toward others, or lack of constraint. Reflects immaturity and age-inappropriate behaviors | “You can’t answer again. It’s my turn!” |

| Complaining | ||||

| Avoidant | 2.11 (1.13) | 1–5 | The extent to which the mother physically orients herself away from the child in such a manner as to avoid interaction | Looks down or away after child speaks |

| Recoiling; detached | ||||

| Neglecting/Distancing | 2.53 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother minimizes the amount of time, contact, or effort she expends on the child; ignoring or psychological/physical distancing in the interaction situation | “Take care of it yourself” |

| Sitting passively while child completes task; pushing child away | ||||

| Indulgent/Permissive | 1.76 (1.36) | 1–7 | The degree to which the mother is excessively lenient and tolerant of the child’s misbehavior or has given up attempts to control the child; a laissez faire or a defeated attitude by the mother regarding the child’s behavior | “Do what you want, you don’t listen to me anyway” |

| Few attempts to get child to comply with task; acting more like a peer than a parent | ||||

| Inconsistent Discipline | 1.82 (1.52) | 1–7 | The degree of maternal inconsistency and lack of follow through in maintaining and adhering to the rules and standards of conduct for the child’s behavior | “I just couldn’t see grounding you for the whole month, so I let you out of your punishment” |

| Idle threats; giving up on instructions | ||||

| Sadness | 4.97 (1.44) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as despondence, unhappiness, sadness, depression, and regret | “I feel stuck here forever” |

| Crying; listless; head in hands | ||||

| Anxiety | 4.60 (1.58) | 1–8 | Emotional distress expressed as nervousness, fear, tension, stress, worry, and concern | “I’m really worried” |

| Fidgeting; tense, rigid body movements | ||||

| Externalized Negative | 3.62 (1.65) | 1–7 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding people, events, or things outside the immediate setting | “Those two are really troublemakers” |

| Complaints; impatience | ||||

| Externalized Negative—Cancer | 2.91 (1.70) | 1–8 | Negativity expressed in the form of anger, hostility, or criticisms regarding cancer treatment and its effects | “I hate chemo” |

| Complaints; impatience |

Note. IFIRS = Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales; Range 1 (absence) to 9 (mainly characteristic).

Maternal Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

At T1, mothers completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990) and the BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI-II and the BAI each contain 21 items rated on a four-point scale from 0 (no change/not at all) to 3 (substantial change/severe). Both measures have good reliability and validity and yield summary scales that are clinically meaningful. Internal consistency in the current sample was excellent (BDI-II α = .94; BAI α = .92).

Maternal PTSS

At T1, mothers reported their PTSS on the IES-R (Weiss & Marmar, 1996). Mothers were asked to answer items “using your child’s cancer and treatment as the stressful event.” The IES-R is composed of 22 items rated on a five-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) that assess symptoms in the past 7 days. It demonstrates good reliability and validity and yields a clinically meaningful summary scale. Internal consistency in the current sample was excellent (α = .94).

Data Analyses

Ms, SDs, and skewness and kurtosis were examined for all variables of interest. Bivariate correlations were computed to examine relations among manifest communication variables and distress measures. Although not all ICCs were >.80 for IFIRS codes, all variables were retained and magnitudes of factor loadings were monitored (Brown, 2015). Because the current sample was not large enough to draw comparisons systematically across age groups, age was partialled out of correlations. Preliminary statistical analyses were conducted with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (SPSS, 2016).

CFA was conducted with Amos (Arbuckle, 2013) using ML estimation. For model identification purposes, one factor loading for each latent variable was set to 1.0 and factor variances were estimated. The model proposed five first-order factors (see Figure 1), each with its own error term. Warm and Structured Communication were specified as two indicators of a second-order Positive Communication factor, and Hostile/Intrusive and Withdrawn Communication were specified as two indicators of a second-order Negative Communication factor. The fifth factor was Expression of Negative Affect. Power was calculated for the test of close fit (with root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] > .05) and was .85 (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996). Parameter estimates were first examined for indications of an improper solution (e.g., negative variance estimates). Fit was evaluated with standardized residual covariances, the RMSEA (Steiger & Lind, 1980), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the nonnormed fit index (NNFI; Bentler & Bonett, 1980).

After examining results from CFA, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted with Comprehensive Exploratory Factor Analysis version 3.04 (Browne, Cudeck, Tateneni, & Mels, 2010). The Maximum Wishart Likelihood discrepancy function was used to fit the model. An oblique Geomin rotation was used.1 Multiple methods were used to determine the number of common factors, considering both guidelines with arbitrary cutoffs as well as those requiring subjective interpretation (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2011). Multiple indices of model fit were examined, and criteria based on discrepancy of approximation (which reflect verisimilitude) and overall discrepancy (which reflect generalizability) were both strongly considered (Preacher et al., 2013). Patterns of factor loadings were also compared and interpreted with theoretical considerations. Ultimately, a solution was chosen that represented a balance of interpretability, parsimony, theory, and model fit (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2011).

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine relations between maternal distress (depression, anxiety, and PTSS) at T1 and maternal communication (based on factor analysis results) at T2 using Amos. SEM was chosen to examine relations between measured (manifest) variables and latent variables. Summary scales for each measure of distress were used in analyses, as they are commonly used in pediatric research and are clinically meaningful. All regressions were conducted using FIML estimation via the Amos program of SPSS (Arbuckle, 2013). FIML makes fewer assumptions about missingness and is more robust to violations of such assumptions compared with many other methods for handling missing data such as listwise deletion, casewise deletion, or simple imputation (Widaman, 2006).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

IFIRS variables are reported in Table I. Correlations among communication variables generally indicated moderate relations among variables on proposed factors. For all communication and distress variables, skewness was <3 and kurtosis was <8. The pattern of skewness for communication variables indicated that raters infrequently scored mothers high on negative communication. Maternal anxiety symptoms (M = 11.50, SD = 9.54; range 0–41; N = 115 mothers), depressive symptoms (M = 13.56, SD = 10.29; range 0–50; N = 114 mothers), and PTSS (M = 27.27, SD = 17.31; range 0–77; N = 113 mothers) reflected mild to moderate levels of distress. There were significant positive correlations among the measures of maternal distress (r = .65–.68, all p < .01), suggesting they were related yet still represented distinct constructs.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The solution for the initial CFA was inadmissible due to negative variances; this was true for both the first-order five-factor model and the hierarchical model. An iterative approach was taken with the first-order model to examine modifications that would result in an admissible solution. This included combining Warm and Structured factors into a single Positive Communication factor, as they were highly correlated, and moving a single code with a negative loading to a different factor. After finding an admissible solution with four factors (Positive Communication, Withdrawn, Hostile/Intrusive, and Expression of Negative Affect), model fit indices nonetheless reflected poor fit. RMSEA was mediocre to unacceptable (.09), and NNFI and SRMR were within the unacceptable range (.77 and .11, respectively). Further, multiple standardized residual covariances were above the traditional cutoff of 1.96, and several were above the conservative cutoff of 2.58 (Brown, 2015). Adding a second-order Negative Communication factor did not improve fit. Modification indices were also examined, but there were no strong theoretical arguments for modifications suggested. Taken together, results from the CFA suggested poor fit for the hypothesized structure; therefore, an EFA was conducted.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Multiple methods were used to determine the optimal number of factors. First, the Kaiser criterion for initial approximation of number of factors was used by examining the number of eigenvalues that were >1.0 (Guttman, 1954), and six were >1 (6.54, 2.30, 1.96, 1.53, 1.29, and 1.05), implying that six factors should be retained. The scree test (Cattell, 1966) was also used; the last large drop occurred between five and six factors, implying that five factors should be retained. Next, oblique rotations were conducted for models with four to seven factors. RMSEA results suggested that a model with six factors provided close fit, RMSEA = .041; 90% confidence interval, CI = [.000, .064], with more factors not providing substantial incremental improvement. Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) values were also lowest for six factors (AIC = 3.925). Finally, in tests of close fit and perfect fit using RMSEA, results indicated that hypotheses of perfect fit in the population were rejected for five factors, but not six factors, suggesting that a six-factor model is plausible. Taken together, criteria based on discrepancy of approximation (RMSEA) and overall discrepancy (AIC) both suggested that six factors would be optimal. Loading patterns were evaluated for both the five-factor and the six-factor model and were carefully considered; the six-factor model was judged to be more readily interpretable and theoretically supported. Ultimately, the six-factor model was retained based on considerations of model fit, interpretability, parsimony, and theory (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2011).

Factor loadings are reported in Table II. Factor 1 had loadings for Positive Reinforcement, Child Monitoring, Warmth, Listener Responsiveness, Communication, Prosocial, Child Centered, and Positive Mood codes (.52–.95) and was termed Positive Communication. Factor 2 had loadings for Indulgent Permissive, Inconsistent Discipline, and Parental Influence (.31–.87) and was termed Inconsistent Communication. Factor 3 had loadings for Externalized Negative, Sadness, and Anxiety (.30–.81) and was termed Expression of Negative Affect. Factor 4 had loadings for Lecture/Moralizing and Externalized Negative Cancer codes (.26–.42) and was termed Lecturing. Factor 5 had loadings for Hostility, Intrusive, Denial, Guilty Coercion, and Antisocial codes (.36–.83) and was termed Hostile/Intrusive Communication. Finally, Factor 6 had loadings for Avoidance and Neglect/Distancing codes (.40–.47) and was termed Withdrawn Communication. In Figure 1, manifest variables were depicted loading onto the single latent variable for which they had the largest factor loading.

| Code . | Factor 1 . | Factor 2 . | Factor 3 . | Factor 4 . | Factor 5 . | Factor 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | 0.52 | 0.08 | −0.25 | 0.41 | 0.05 | −0.02 |

| Child Monitoring | 0.71 | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| Warmth | 0.63 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.37 | −0.13 | 0.13 |

| Listener Responsiveness | 0.78 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.34 |

| Communication | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Prosocial | 0.74 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.07 |

| Child Centered | 0.95 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| Positive Mood | 0.56 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.51 | −0.12 | −0.01 |

| Indulgent Permissive | −0.05 | 0.78 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.02 |

| Inconsistent Discipline | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Parental Influence | −0.02 | 0.31 | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| Sadness | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.11 |

| Anxiety | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.81 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Externalized Negative | −0.17 | −0.07 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.16 | −0.01 |

| Lecture Moralizing | −0.27 | −0.18 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Externalized Negative Cancer | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.06 | −0.17 |

| Hostility | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.83 | −0.04 |

| Intrusive | −0.31 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.02 |

| Denial | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Guilty Coercion | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.17 | 0.42 | −0.30 |

| Antisocial | −0.28 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.05 |

| Avoidance | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| Neglect Distancing | −0.37 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

| Code . | Factor 1 . | Factor 2 . | Factor 3 . | Factor 4 . | Factor 5 . | Factor 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | 0.52 | 0.08 | −0.25 | 0.41 | 0.05 | −0.02 |

| Child Monitoring | 0.71 | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| Warmth | 0.63 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.37 | −0.13 | 0.13 |

| Listener Responsiveness | 0.78 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.34 |

| Communication | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Prosocial | 0.74 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.07 |

| Child Centered | 0.95 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| Positive Mood | 0.56 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.51 | −0.12 | −0.01 |

| Indulgent Permissive | −0.05 | 0.78 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.02 |

| Inconsistent Discipline | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Parental Influence | −0.02 | 0.31 | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| Sadness | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.11 |

| Anxiety | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.81 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Externalized Negative | −0.17 | −0.07 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.16 | −0.01 |

| Lecture Moralizing | −0.27 | −0.18 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Externalized Negative Cancer | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.06 | −0.17 |

| Hostility | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.83 | −0.04 |

| Intrusive | −0.31 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.02 |

| Denial | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Guilty Coercion | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.17 | 0.42 | −0.30 |

| Antisocial | −0.28 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.05 |

| Avoidance | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| Neglect Distancing | −0.37 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

Note. Bolded factor loadings are >.25. Manifest variables were depicted loading onto the single latent variable for which they had the largest factor loading. The highest loading for each manifest variable across factors is shaded; shaded factor loadings reflect items thought to be representative of the factor. Factor 1 = Positive Communication, Factor 2 = Inconsistent Communication, Factor 3 = Expression of Negative Affect, Factor 4 = Lecturing, Factor 5 = Hostile/Intrusive Communication, Factor 6 = Withdrawn Communication. N = 115.

| Code . | Factor 1 . | Factor 2 . | Factor 3 . | Factor 4 . | Factor 5 . | Factor 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | 0.52 | 0.08 | −0.25 | 0.41 | 0.05 | −0.02 |

| Child Monitoring | 0.71 | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| Warmth | 0.63 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.37 | −0.13 | 0.13 |

| Listener Responsiveness | 0.78 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.34 |

| Communication | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Prosocial | 0.74 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.07 |

| Child Centered | 0.95 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| Positive Mood | 0.56 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.51 | −0.12 | −0.01 |

| Indulgent Permissive | −0.05 | 0.78 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.02 |

| Inconsistent Discipline | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Parental Influence | −0.02 | 0.31 | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| Sadness | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.11 |

| Anxiety | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.81 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Externalized Negative | −0.17 | −0.07 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.16 | −0.01 |

| Lecture Moralizing | −0.27 | −0.18 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Externalized Negative Cancer | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.06 | −0.17 |

| Hostility | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.83 | −0.04 |

| Intrusive | −0.31 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.02 |

| Denial | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Guilty Coercion | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.17 | 0.42 | −0.30 |

| Antisocial | −0.28 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.05 |

| Avoidance | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| Neglect Distancing | −0.37 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

| Code . | Factor 1 . | Factor 2 . | Factor 3 . | Factor 4 . | Factor 5 . | Factor 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | 0.52 | 0.08 | −0.25 | 0.41 | 0.05 | −0.02 |

| Child Monitoring | 0.71 | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| Warmth | 0.63 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.37 | −0.13 | 0.13 |

| Listener Responsiveness | 0.78 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.34 |

| Communication | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.05 |

| Prosocial | 0.74 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.07 |

| Child Centered | 0.95 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| Positive Mood | 0.56 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.51 | −0.12 | −0.01 |

| Indulgent Permissive | −0.05 | 0.78 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.02 |

| Inconsistent Discipline | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Parental Influence | −0.02 | 0.31 | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| Sadness | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.11 |

| Anxiety | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.81 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Externalized Negative | −0.17 | −0.07 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.16 | −0.01 |

| Lecture Moralizing | −0.27 | −0.18 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Externalized Negative Cancer | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.06 | −0.17 |

| Hostility | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.83 | −0.04 |

| Intrusive | −0.31 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.02 |

| Denial | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Guilty Coercion | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.17 | 0.42 | −0.30 |

| Antisocial | −0.28 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.05 |

| Avoidance | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| Neglect Distancing | −0.37 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

Note. Bolded factor loadings are >.25. Manifest variables were depicted loading onto the single latent variable for which they had the largest factor loading. The highest loading for each manifest variable across factors is shaded; shaded factor loadings reflect items thought to be representative of the factor. Factor 1 = Positive Communication, Factor 2 = Inconsistent Communication, Factor 3 = Expression of Negative Affect, Factor 4 = Lecturing, Factor 5 = Hostile/Intrusive Communication, Factor 6 = Withdrawn Communication. N = 115.

The observed pattern of correlations among factors was consistent with expectations and with the labels selected for each factor. Expression of Negative Affect was not strongly correlated with any of the five communication factors (r’s < .20). Positive Communication was negatively correlated with all other factors and most strongly with Hostile/Intrusive (r = −.46). Hostile/Intrusive was most strongly, positively correlated with Inconsistent Communication (r = .35) and Withdrawn Communication (r = .21). Correlations among these factors were not universally large in magnitude, suggesting that a higher-order factor would not be suitable.

Prospective Relations Between Maternal Distress and Maternal Communication

For SEM analysis, latent variables for communication were created based on EFA, and child age was controlled for by regressing each manifest variable onto age. Latent communication variables at T2 were predicted from manifest distress variables at T1. Distress symptoms were examined separately for each measure (anxiety, depression, and PTSS). Model fit was good for each (RMSEA < .06). Results are reported in Table III.

SEM: Maternal Distress Symptoms as Predictors of Latent Variables of Maternal Communication

| . | Predictor variables . | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms . | Depression symptoms . | PTSS . | |||||||||||||

| . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . |

| Outcome variables | |||||||||||||||

| Hostile/Intrusive Communication | .06 | .01 | [.03–.08] | .41*** | .17 | .06 | .01 | [.04–.08] | .50*** | .25 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .26* | .07 |

| Lecturing | .00 | .02 | [−.03–.04] | .06 | .01 | .01 | .02 | [−.02–.04] | .20 | .04 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .31* | .09 |

| Withdrawn Communication | .00 | .01 | [−.02–.02] | .07 | .01 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .22 | .05 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .21 | .05 |

| Inconsistent Communication | .02 | .01 | [0–.04] | .21* | .04 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .13 | .02 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .18 | .03 |

| Positive Communication | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.02 | .01 | [−.03–.00] | −.27* | .07 |

| Expression of Negative Affect | .02 | .01 | [−.01–.04] | .17 | .03 | .02 | .01 | [0–.05] | .27* | .07 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .32* | .11 |

| . | Predictor variables . | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms . | Depression symptoms . | PTSS . | |||||||||||||

| . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . |

| Outcome variables | |||||||||||||||

| Hostile/Intrusive Communication | .06 | .01 | [.03–.08] | .41*** | .17 | .06 | .01 | [.04–.08] | .50*** | .25 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .26* | .07 |

| Lecturing | .00 | .02 | [−.03–.04] | .06 | .01 | .01 | .02 | [−.02–.04] | .20 | .04 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .31* | .09 |

| Withdrawn Communication | .00 | .01 | [−.02–.02] | .07 | .01 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .22 | .05 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .21 | .05 |

| Inconsistent Communication | .02 | .01 | [0–.04] | .21* | .04 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .13 | .02 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .18 | .03 |

| Positive Communication | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.02 | .01 | [−.03–.00] | −.27* | .07 |

| Expression of Negative Affect | .02 | .01 | [−.01–.04] | .17 | .03 | .02 | .01 | [0–.05] | .27* | .07 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .32* | .11 |

p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Notes. All symptoms listed are maternal symptoms self-reported near time of child’s diagnosis (T1). All maternal communication observed 3 months later (T2). RMSEA < .06 for each model. Each distress measure entered separately in regression analyses. Anxiety symptoms measured with the BAI (Beck Anxiety Inventory), depression symptoms measured with the BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory), and PTSS measured with the IES-R (Impact of Events Scale-Revised). IFIRS data were available for all N = 115 mothers. N = 115 mothers completed the BAI; N = 114 mothers completed the BDI-II; N = 113 mothers completed the IES-R.

Hypothesized Structure tested with CFA Structure suggested by EFA.

BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; IES-R . Impact of Events Scale-Revised; CI = confidence interval; CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; EFA = exploratory factor analysis; PTSS = posttraumatic stress symptom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SEM = structural equation modeling.

SEM: Maternal Distress Symptoms as Predictors of Latent Variables of Maternal Communication

| . | Predictor variables . | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms . | Depression symptoms . | PTSS . | |||||||||||||

| . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . |

| Outcome variables | |||||||||||||||

| Hostile/Intrusive Communication | .06 | .01 | [.03–.08] | .41*** | .17 | .06 | .01 | [.04–.08] | .50*** | .25 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .26* | .07 |

| Lecturing | .00 | .02 | [−.03–.04] | .06 | .01 | .01 | .02 | [−.02–.04] | .20 | .04 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .31* | .09 |

| Withdrawn Communication | .00 | .01 | [−.02–.02] | .07 | .01 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .22 | .05 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .21 | .05 |

| Inconsistent Communication | .02 | .01 | [0–.04] | .21* | .04 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .13 | .02 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .18 | .03 |

| Positive Communication | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.02 | .01 | [−.03–.00] | −.27* | .07 |

| Expression of Negative Affect | .02 | .01 | [−.01–.04] | .17 | .03 | .02 | .01 | [0–.05] | .27* | .07 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .32* | .11 |

| . | Predictor variables . | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms . | Depression symptoms . | PTSS . | |||||||||||||

| . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . | b . | SE . | CI . | β . | R2 . |

| Outcome variables | |||||||||||||||

| Hostile/Intrusive Communication | .06 | .01 | [.03–.08] | .41*** | .17 | .06 | .01 | [.04–.08] | .50*** | .25 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .26* | .07 |

| Lecturing | .00 | .02 | [−.03–.04] | .06 | .01 | .01 | .02 | [−.02–.04] | .20 | .04 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .31* | .09 |

| Withdrawn Communication | .00 | .01 | [−.02–.02] | .07 | .01 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .22 | .05 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .21 | .05 |

| Inconsistent Communication | .02 | .01 | [0–.04] | .21* | .04 | .01 | .01 | [0–.03] | .13 | .02 | .01 | .01 | [.00–.02] | .18 | .03 |

| Positive Communication | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.03 | .01 | [−.05– −.01] | −.28** | .08 | −.02 | .01 | [−.03–.00] | −.27* | .07 |

| Expression of Negative Affect | .02 | .01 | [−.01–.04] | .17 | .03 | .02 | .01 | [0–.05] | .27* | .07 | .02 | .01 | [.00–.03] | .32* | .11 |

p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Notes. All symptoms listed are maternal symptoms self-reported near time of child’s diagnosis (T1). All maternal communication observed 3 months later (T2). RMSEA < .06 for each model. Each distress measure entered separately in regression analyses. Anxiety symptoms measured with the BAI (Beck Anxiety Inventory), depression symptoms measured with the BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory), and PTSS measured with the IES-R (Impact of Events Scale-Revised). IFIRS data were available for all N = 115 mothers. N = 115 mothers completed the BAI; N = 114 mothers completed the BDI-II; N = 113 mothers completed the IES-R.

Hypothesized Structure tested with CFA Structure suggested by EFA.

BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; IES-R . Impact of Events Scale-Revised; CI = confidence interval; CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; EFA = exploratory factor analysis; PTSS = posttraumatic stress symptom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SEM = structural equation modeling.

Anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and PTSS were each significant positive predictors of Hostile/Intrusive Communication (β = .41, β = .50, β = .26, respectively). PTSS was a significant positive predictor of Lecturing (β = .31, p < .05). Anxiety symptoms were a significant positive predictor of Inconsistent Communication (β = .21, p < .05). Depressive symptoms and PTSS were both significant positive predictors of Expression of Negative Affect (β = .27, β = .32, respectively). There were no significant predictors of Withdrawn Communication. And finally, anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and PTSS were each significant negative predictors of Positive Communication (β = −.28, β = −.28, β = −.27).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate maternal communication in pediatric cancer, first by determining its structure with factor analysis, and second by examining its relation to maternal distress over time with SEM. This is the first study to evaluate maternal communication in pediatric cancer using factor analytic methods, providing a comprehensive understanding of the underlying structure and organization of maternal communication. This study also builds on the previous literature by identifying prospective relations between three domains of maternal distress and latent variables of maternal communication 3 months later. Findings suggest that whereas symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSS may be uniquely related to different aspects of maternal negative communication, each may impair mothers’ ability to communicate positively with their children. Results provide a nuanced understanding of maternal communication in this at-risk pediatric sample and identify prospective pathways of risk between maternal distress and communication that can be targeted in intervention.

The hypothesized model tested in CFA had anchors in warmth and control, grounded in Baumrind’s (1968) seminal theory of parenting and adapted for pediatric populations (Murphy et al., 2017). However, because the model tested in CFA demonstrated poor fit, EFA was used and suggested a structure that differed from hypotheses in two primary ways—first, the unitary nature of Positive Communication, and second, the number and nature of negative communication patterns. These latent variables suggest that warmth and control appeared inextricable in the current sample (with one Positive Communication factor), while negative communication appeared to have multiple representations (Hostile/Intrusive, Withdrawn, Lecturing, and Inconsistent Communication). Two of these latent variables were consistent with hypothesized Hostile/Intrusive and Withdrawn communication patterns, while the other two were unexpected. Thus, the resulting model of maternal communication was neither symmetrical nor hierarchical, as originally hypothesized.

The final model also differed from the two previous EFA studies of the IFIRS (Raj et al., 2014; Williamson et al., 2011). While these studies used distinct sets of IFIRS codes and were conducted with different samples (mothers of children with TBI and low-income marital dyads), their results indicated three factors termed Positivity/Warm (e.g., Positive Mood and Warmth/Support codes), Negativity (e.g., Hostility code), and Effectiveness (e.g., Communication code). However, in this study, multiple codes from the Positivity/Warm and Effective factors loaded onto the same factor labeled here as Positive Communication, appearing to tap a single latent construct, whereas codes from the “Negative” factor clustered separately, appearing to tap different latent constructs. There are several reasons why these results differed from previous findings. For example, previous studies combined codes across dyadic partners (including duplicate codes for husbands and wives) and made different analytical decisions (e.g., determining the number of factors exclusively with scree plots, using orthogonal rotations). However, results also suggest that maternal communication may be organized differently in the current sample. It is possible that this study captured a snapshot of communication during a specific and exceptional time in families’ lives.

Whereas results from EFA characterized the number and nature of communication patterns, results from SEM identified significant predictors of these patterns. The direction of the relations between maternal symptoms of distress and maternal communication was consistent with hypotheses: symptoms of maternal distress were positively correlated with negative communication patterns (Hostile/Intrusive, Lecturing, and Inconsistent) and with Expression of Negative Affect and were negatively correlated with Positive Communication. Specifically, all of the domains of distress (anxiety, depression, and PTSS) were similarly correlated with Positive Communication but uniquely correlated with different aspects of negative communication. Additionally, both depressive symptoms and PTSS were significantly, positively related to Expression of Negative Affect. Below, we briefly review each latent variable of communication and the symptoms that predicted it.

The pattern of loadings onto the Positive Communication factor suggests that warmth and control were strongly interrelated in the current sample. Mothers may have been carrying out two important tasks, providing information and conveying emotional support, simultaneously for their children. All three measures of distress (anxiety, depression, and PTSS) were significant, negative predictors of Positive Communication. This is consistent with previous research examining parental distress and positive communication in type 1 diabetes (Jaser & Grey, 2010) and pediatric asthma (Lim et al., 2008).