-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Barbara Becnel, Racism, public pedagogy, and the construction of a United States values infrastructure, 1661–2023: a critical reflection, Journal of Philosophy of Education, Volume 58, Issue 2-3, April-June 2024, Pages 289–307, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopedu/qhad054

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

This paper argues that public pedagogy—an educational activity that takes place outside of the traditional classroom setting—has had a potent impact on the history of racism in the United States of America (USA). Yet this paper questions why the education academy’s scholarship has not shown a commensurate focus on the subdiscipline of public pedagogy, particularly racialized public pedagogy. I explore these topics by first examining a fateful confluence of historical circumstances involving slave codes and indentured servant laws governing low-income white workers, laws passed by the Barbados Assembly in 1661, that made their way across the Atlantic to be lifted, word for word, by leaders of colonial territories that became the USA. These laws ended up regulating not only the legal status of black slaves and white indentured servants in the USA, but also regulating social relations between those same black and white people. The resulting black–white social relations led to the evolution of racialized customs in what eventually became the USA, inspiring practices that undergirded black inferiority and white superiority for hundreds of years. Those customs contributed to the construction of what I have labelled a United States (US) values infrastructure dominated by racism, which I contend is a racialized values infrastructure that exists to this day. To gain more insight into this phenomenon, this paper considers the question: how might the complexity of racialized public pedagogy be addressed in the scholarship of education literature and be imagined in a way to fit into an anti-racist curriculum?

At the root of the American Negro1 problem is the necessity of the American White man to find a way of living with the Negro in order to be able to live with himself. (James Baldwin, ‘Stranger in a Village’, in Notes of a Native Son, 1955)

Overview: in search of a conceptual spine for racism in the United States of America

In the above quotation, James Baldwin highlights a dilemma for the United States of America’s (USA) white citizens that he states is at the core of what constitutes the ‘American Negro problem’ (Baldwin 1955: 172). That problem, as described by Baldwin, has been the need for the nation’s white populace to devise a societal mechanism of some sort that ensures a white citizenry’s capacity to best serve itself while having to share the USA with a growing population of black people whose ancestors were at one time enslaved by members of that white citizenry. This, of course, sets up a socio-political framework for US racism that serves as a crucible for Baldwin’s analysis. With this paper, I follow, to some extent, Baldwin’s lead.

Here I explore what I argue is the existence of a racialized values infrastructure in the USA, which I further argue is the societal mechanism being utilized—wittingly or unwittingly, to be discussed later—by a white citizenry to maintain a generational belief in its superiority over the nation’s black populace. My claim is that this racialized values infrastructure has, for nearly four centuries, embedded a belittling belief system about black people into the customs, laws, and institutional development of the country. Consequently, such a belief system, which for hundreds of years has belittled black people, has transformed, I contend, into a national common understanding of black diminishment. In other words, that common understanding of the inferior status of black people and the superior status of white people has become a national value, whose origins and subsequent evolution into a full-fledged racialized US values infrastructure are analysed throughout this paper.

With this work I focus on how racialized history, law, and politics intermingled and, by so doing, fostered potent opportunities for racialized outside-the-classroom educational practices—also known as public pedagogy—that endure to this day. My contention is that a range of black-derogating public pedagogical practices conducted over hundreds of years has functioned as propaganda, educating millions of people to absorb a racialized belief system. As expressed by Robbin Henderson, director of the Berkeley Art Center, ‘Derogatory imagery enables people to absorb stereotypes, which in turn allows them to ignore and condone injustice, discrimination, segregation, and racism’ (Faulkner et al. 1982: 11). As such, the politicized public pedagogy of racist cartoons, posters, videos, and other imagery has played a vital role in the entrenchment of race-based values in the US national culture.

Finally, this paper argues there is at least a hint of politics in how public pedagogical topics are examined—or not examined—through the lens of the scholarship of education. The many forms of public pedagogy provide powerful methods for educating large numbers of people. Yet, I was informed early on in my doctoral studies by a PhD supervisor that the public pedagogical literature was ‘quite thin’. My question is this: given the potency of some public pedagogical practices, why is it so thin? In my attempt to answer that question, this paper begins an examination of the politics of public pedagogy in the scholarship of education, which is entangled, I argue, with the need to decolonize that scholarship. I use the word ‘begins’ purposefully because interrogating the political motivations of an academic discipline and its scholars requires far more than one voice, one assessment of the same. What I hope to achieve, then, with this paper is for it to serve as a provocation that enlists scholars of education and of other disciplines to participate in this critique. Presented later in this paper are more fulsome discussions of the following topics: racialized public pedagogy as a concept; some long-standing applications of racialized public pedagogy as propaganda; and an historical analysis of why a special counter-intuitive purpose of racialized public pedagogy has, in fact, prevailed generationally.

My positionality for this paper emerges from the interdisciplinary research I conducted for my University of Edinburgh PhD project in the Moray House School of Education and Sport, and in the School of Law. As a black woman from California, I had engaged in a nineteen-year immersive ethnographic research practice to study the killing culture of black street gangs in Los Angeles, particularly as acted out by the gang leadership of the nation’s two most iconic black gangs, the Crips and the Bloods. I define ‘immersive’ as spending an average of twelve hours a day tagging along with the leaders of the PJ Watts Crips and the Bounty Hunter Bloods, gangs representing two public housing projects in Watts, California, also known as part of South-Central Los Angeles.

The title of my thesis is, “Culture of the Condemned: A Critique of How Death Row Became a Symbol of Heroism for America’s Street-Gang Generation”. My goal was to assess how a killing culture evolved among the black gangster class in South-Central Los Angeles, rather than to narrow my focus to study only what black gangsters do every day. My argument was that the USA’s very long history of racism, starting with slavery, needed to claim significant responsibility for how a culture of the condemned situated itself into that nation’s urban enclaves. I focused on three conceptual strands—duality, agency, and freedom—and tracked those strands through 400 years of racialized US history. My contention is those three concepts embedded in the racism of the USA contributed to an evolution of black gangster characteristics that support a violent street culture. My research led me to secure a copy of the original Barbados Slave Codes of 1661, which were adopted by leaders in colonial America, and to initiate an analysis of the subsequent legal and social impacts of those slave codes, which I conceptualized as undergirding the construction of a racialized values infrastructure in the USA. As pertaining to my PhD research, I argue the country’s racialized values infrastructure spawned a public pedagogical practice that functioned as racist propaganda to stereotype and stigmatize the black gangster class. These concepts, insights, and arguments have readily found their way into this paper, though framed to make another point distinct from public pedagogy’s influence on black street gangsters. Here my contention is that racialized public pedagogy as a subdiscipline of the field of education may be contributing to that discipline’s challenge to decolonize its curriculum.

One last note on my positionality for this paper. As a middle-class college-educated black resident of California, I have been impacted both personally and professionally by my doctoral work and its dive into a study of US racialized history. Personally, I have had to navigate my own class-based bias, which had prompted me to predetermine the bad character of the black gangster class and its culture. It took nearly a year of reflexive effort to ameliorate that bias, which then professionally enhanced my scholarship by allowing me to learn about the street gangsters and their environment, as opposed to believing that I already knew who they were and what motivated them. So, I am animated by a social justice instinct to critically examine what has impeded equity and inclusion in various disciplines, including education, and what can be done to promote an altruistic goal of bias-free change.

This work is divided into three additional sections. Part One: ‘Legal Origins of a Racialized Values Infrastructure, 1661–2023’ tracks the history of the construction of racialized laws in the USA, with a focus on the role played by the Barbados Slave Codes of 1661 (McCord 1840; Little 1993; Nicholson 1994; Rugemer 2013). Those slave codes, it turns out, influenced American colonial constitutions, subsequent US law (Santos and Bickel 2017), and established what I argue is a racialized values infrastructure for the nation that exists today. ‘Politics of a Public Pedagogy for the Oppressed’, Part Two, explores how racialized customs and cultural propaganda that educated the mainstream populace to disdain black people emerged from black-defining slave laws and practices of centuries past. Additionally, such disdainful perspectives towards black people in the USA are present in today’s customs and culture, and often expressed in ways remarkably like visual and verbal depictions of the USA’s black populace from more than 100 years ago. This section focuses on the legacy of racist cartoons as one prominent example of propagandized public pedagogy. In Part Three: ‘Imagining/Reimagining Public Pedagogical Politics of the Education Academy’, I question why public pedagogy, such a powerful educational tool, particularly given its prolific use as a tool to promote racial discrimination, is not shown nearly as much interest as an area of study versus what happens in a classroom or even a museum. Is there a political or other kind of bias in the education academy against public pedagogy as a legitimate subfield? If so, what could be the motivating factors contributing to such bias? And how might an experience of bias in public pedagogical scholarship be mitigated?

This paper, then, seeks to identify as well as critically examine what I argue is the conceptual spine—the nation’s racialized values infrastructure—that accounts for the customs, laws, and public pedagogical practices established to perpetuate racism in the USA for nearly 400 years.

Part one: legal origins of a racialized values infrastructure, 1661–2023

The legal system that governed slavery in the American colonies in the 1600s was borrowed from another country, Barbados, a Caribbean Island that was a British slave society during that era. By 1661, it turns out, the British aristocracy that ruled Barbados had decided to codify that country’s slave customs into law (Handler 2016; Handler and Reilly 2017; Little 1993; Rugemer 2013; Sirmans 1962), which set into motion an historic circumstance of ‘coding borrowing’ that involved the colonies (Nicholson 1994: 41).

For many years, the leadership of Barbados had been satisfied with controlling its slave population via the rules of subservient slave behaviour dictated by many decades of such behaviour being the accepted practice or custom (p. 41). But as fear escalated among sugar plantation owners that the slaves they unofficially controlled might revolt against brutal conditions, that plantocracy pressed for more official control over slaves. They pressed for slave customs to be converted to slave laws, also known as slave codes. On 27 September 1661, the Barbados Assembly passed what became an iconic piece of legislation: An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes, otherwise known as the Barbados Slave Codes of 1661. These codes literally defined black people—in the worst of ways. Black people, for instance, called Negroes, were deemed synonymous with slaves. Where the word ‘slave’ was used in the legislation, it automatically referred to a Negro—and the reverse was true. The words ‘Negro’ and ‘slave’ defined each other, thus encouraging a perception that all black people, even free black people, were slaves. The introductory paragraph to the slave codes further set the stage for a devastating process of identity formation to be imposed on slaves, alias Negroes:

Given the dangerous and animalistic nature of black people described in the opening pages of the slave code legislation, there were other clauses that followed, which detailed violently cruel punishments against slaves for not adhering to the codes:The said Negroes … are of barbarous, wild and savage nature, and such as renders them wholly unqualified to be governed by the Laws, Customs and Practices of our Nation [Barbados]: It therefore becoming absolutely necessary, that such other Constitutions, Laws and Orders, should be in this island framed and enacted for the good regulating or ordering of them, as may both refrain the disorders, rapines and inhumanities to which they are naturally prone and inclined (Hall 1764: 112, 113).

After the Barbados Slave Codes of 1661 were passed into law, John Colleton, a British 1st Baronet, who had already been gifted property charters by the British Crown for Barbados and for an American colony soon to be named South Carolina, made an historically fortuitous connection: he began corresponding with John Locke (Sirmans 1962). Sir John Colleton had been so privileged with property because of his status as a member of the British aristocracy and because of the Crown’s common practice to offer land to selected aristocrats to generate profits operating plantations in British colonies of the New World (Tree 1977). Locke was considered the father of liberalism and had even served as the inspiration for Thomas Jefferson when he was writing a draft of the Declaration of Independence for the American colonies. In 1689, in his classic Two Treatises of Government, Locke espoused the view that all humans—except for slaves, as was later revealed—had inalienable rights to life, liberty, and ‘estates of the people’, which for Locke meant the ‘property’ of the people (Locke 1689: Section 222). And slaves were considered property, as was land, buildings, and other belongings. Thomas Jefferson made one small change to Locke’s refrain for the Declaration of Independence (1776). Jefferson wrote: ‘ … life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ (Paragraph 2). But Jefferson, like thought-leader-of-liberalism Locke, maintained inconsistent ethics when it came to his values regarding racism, and thus the promotion of goodwill for all members of humanity. Jefferson, it turns out, did not believe black slaves to be entitled to pursue their own definition of happiness or liberty of any kind. Jefferson himself owned black slaves and had maintained a sexual relationship for many years with one such black slave, Sally Hemings (Gordon-Reed 1997). That relationship began when Hemings was around fourteen years old. Jefferson went on to sire six children with Hemings. White wealthy aristocrats in Virginia, where Jefferson resided, were known to have sexual relations with the slaves they owned (Rothman 2003). All that was expected of them was to be discreet. Jefferson, then, was acting in line with his community’s culture.If any Negro Man or Woman slave offer any violence to any Christian [white European] by striking or the like [, ] the Negro Slave for his and her first offence … would be severely whipped by the Constable. … For his second offence of that nature [, ] he shall be severely whipped [, ] his nose slit [, ] and be burned in some part of his face with a hot iron.2

This anecdotal history highlights what I argue represents a commonplace but critical practice of racialized denial in white colonial America, which I contend persists in the present-day USA. Philosopher Charles Mills labels such behaviour ‘strategic epistemic ignorance’, reflecting an active interest by those who dominate society in not viewing the world, nor their behaviour in the world, as being ethically inconsistent or even wrong (Alcoff 2007). Mills explains:

This finding is an important element of what will be discussed later in this paper: the role racism has played as a potent value in US culture, for hundreds of years until today, and the complexity of societal constructions required to deny racism’s harm.[O]n matters related to race … [there exists] an inverted epistemology, an epistemology of ignorance, a particular pattern of localized and global cognitive dysfunction (which are psychologically and socially functional) producing the ironic outcome that whites will in general be unable to understand the world they themselves have made. (Mills 1997: 18)

During the fateful Colleton–Locke correspondence, Locke and Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, were co-authoring the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which ended up with slave code language, including a very harsh explication of the relationship between white colonialists and the black slave: ‘Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his Negro slaves. …’ (as cited in Hsueh 2002; Isenberg 2017; Sirmans 1962: 463). Historian Eugene Sirmans points to Colleton’s likely influence, given Colleton’s knowledge of the Barbados Slave Codes and Colleton’s timely correspondence with Locke, and given what turned up in the text of the Carolina Constitutions that Locke was helping to author.

Slave code borrowing did not stop with the first insertion of codes from Barbados. Over the decades, as Barbados updated the country’s laws related to slaves, American colonies often lifted the legislative clauses, word for word. Twenty-seven years after An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes, the Barbados Assembly amended the old 1661 legislation by shortening its title to An Act for the Governing of Negroes. This new title was symbolic of two dramatic shifts in the slave economy and slave customs of Barbados, which had some impact, at a minimum, on the slave customs of colonial America. In 1627, Barbados was settled by the British and began the development of an agricultural sector based on mixed-crop farming at a small scale, producing food primarily for local consumption (Handler and Reilly 2017). At that time, the labour force mostly comprised slaves, indentured servants, and free colonists. To the extent Barbados functioned as a black slave society, it was based on customs—an unwritten social contract of sorts—not on laws, as already mentioned. But by the mid-1640s, the economy changed very quickly to large-scale sugar cane production for export rather than for local markets. This rapid transformation into an extremely profitable enterprise prompted a demand for significantly more manpower. British leadership in Barbados turned to black enslavement in order to resolve labour shortages. That decision eventually led to a full-scale slave economy in Barbados, accompanied by a fundamental shift in relations between black slaves and the sugar planters, otherwise known as the plantocracy. The title of the 1661 slave code legislation—amended nearly thirty years later with the replacement of phrases such as the ‘Better Ordering’ of Negroes with a more pointed one-word description of what was intended (that is, the intention of ‘Governing’ black slaves)—was symbolic of how the slave–master culture had changed in Barbados. This small Caribbean Island had transformed from a society of harsh customs in their enslavement practices to a society of brutal captivity.

To illustrate, that new law—An Act for the Governing of Negroes—provided more clarity as to the significance of burning a scar onto the face of a disobedient slave. The torturous act was intended to leave permanent, visible evidence for all to see of the bad character of that slave, by branding the slave ‘in the forehead with a hot iron, that the mark thereof may remain’ (Hall 1764: 118). This, too, became a method in colonial America of not only dehumanizing black people but imposing on them a stereotyped identity of overall unworthiness.

Hundreds of years later, further evidence of the brutality enacted against the black slaves of Barbados showed up in a study of their dead bodies found at a burial site that serviced the slave population at the Newton plantation in Barbados from the 1600s to 1800s. The study, conducted by anthropologist Robert Corruccini and three other scholars, focused on craniodental body characteristics in tandem with ethnohistorical research. Their findings were troubling. The life span of a slave in Barbados was only twenty years. Further, skeletal examinations showed signs of those dead slave bodies having experienced ‘periodic near-starvation’ (Corruccini et al. 1982: 443). The University of Houston reports on its website that the USA also recorded short life spans for black slaves especially as relative to white members of colonial America (Digital History 2021). Black slaves, according to the same University of Houston online posting, had a life expectancy of twenty-one or twenty-two years, while the antebellum white population lived to be forty to forty-three years old. US historian Charles S. Sydnor found in a 1930 study that black slaves in Mississippi had a life span ‘not far from the age of 20’ (Sydnor 1930: 566). Also, 50 per cent of black slave babies died before their first birthday, as reported by the University of Houston, and a crucial contributor to such deaths was serious malnourishment. A footnote in Sydnor’s article, ‘Life Span of Mississippi Slaves’, discusses the academic debates about the accuracy of slaves not being sufficiently fed. Given the economic investment in slaves, the argument goes, it would be ‘economically unsound’ for a slave owner not to feed his investment (p. 567). Yet, the skeletal research discussed above found that slave owners did in fact allow their slaves to reach ‘periodic near-starvation’ (Corruccini et al., 1982: 443). In that same footnote, Sydnor himself makes what I would argue is an observation about the dominance of racialized cultural motivation over economic efficacy. ‘However,’ Sydnor states, ‘a practical man is not always an economic man’ (Sydnor 1930: 567). That statement leads into philosopher Charles Mills’ theorizing about strategic epistemic ignorance, which is the active interest not to see what you are doing is wrong. My conceptual frame for Mills’ work is that racialized denial can easily overwhelm common sense. But Mills makes another profound point about the consequences of epistemologies of ignorance involving race and racism. It is possible for white people to construct a world that they do not understand with outcomes that can be antithetical to their best interests, as well as the best interests of others.

Thus, the path slave codes travelled from Barbados to the east coast of the American colonies proved to be of great consequence in the history of the USA. Slave codes became an enduring fixture in the laws of the USA. Slave codes, dubbed le code noir by residents of Louisiana (Stewart 1995: 228), became black codes when slavery was no longer legal in the USA (Santos and Bickel 2017). When the Reconstruction Era ended, and the limited attempt to accept black people as legitimate citizens of the country was rejected, Jim Crow laws quickly replaced black codes to re-establish a de facto master–slave relationship between white and black residents of the USA, bereft of official ownership. But just as slave codes controlled virtually every aspect of a slave’s life, Jim Crow laws certainly made clear what black people were not allowed to do—and the list was long. Black people were required to sit at the back of the bus. Black people were not allowed to drink water from the same public fountains as white people or use the same restrooms. School systems were segregated, so that black girls and boys could not learn by sitting alongside white children. Black people could not live anywhere they wanted to live. There were neighbourhood covenants that legally restricted the sale of homes in many communities to black people. And there were signs posted, as exhibited now at Ferris University’s Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, that explicitly stated: ‘Help Wanted—White Only’.

Ironically, while the Barbados Slave Codes were initially created to convert black enslavement customs to laws, in the hope of ensuring white society’s protection, those same slave codes or laws have, upon their arrival in the American colonies, I argue, strongly contributed to the evolution of racialized colonial customs. And as the Barbados sugar cane industry became the most prosperous in the Caribbean, the stakes became higher: the Barbados codes responded by becoming more controlling, punitive, and racist, which was reflected in language changing from the wanting to be ‘better’ in the governing of black slaves to the outright ‘governing’ of black slaves, with the codes themselves becoming harsher, even more cruel. Meanwhile, colonial America followed suit. But there the harsher codes translated into more harsh and indelibly embedded customs in the culture of American colonial life. And those racialized customs continue to regulate the relationship between black and white citizens of the USA, aided by one additional slave code-era law: An Act for the Good Governing of Servants, and Ordaining the Rights Between Masters and Servants (Handler and Reilly 2017). This law was passed on the same day, 27 September 1661, that An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes was voted into law.

Similar to the slave code legislation where the words ‘slave’ and ‘Negro’ were interchangeable, the word ‘servant’ by definition meant white indentured servant. Negroes were not allowed to be servants, because servants had some limited rights, as referred to in the title of the law itself and could one day be free. Slaves had no rights. They were owned in perpetuity, and all their offspring were automatically slaves from birth until the day they died. The language of the white servant codes also included the word ‘good’ as a prefix to ‘governing’. With white indentured servants, then, the word ‘governing’ was less threatening: it did not carry the tyrannical force, or the connotations of absolute control and domination, that it did for the black slave. I also make such an argument given the context of the use of the word ‘ordaining’, which promotes an enshrining of white indentured-servant rights between masters and servants. White servants, therefore, were better off and thus superior to Negro slaves—by law. These laws were also replicated in the colonies, re-enforcing the sentiments inscribed by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence—‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’—to apply to white indentured servants and then the white working class, but never black slaves. That became a paramount racialized value in colonial America. So, on that September day in 1661, the Barbados Assembly codified into law the separation of slaves and servants, the inferior status of blackness as opposed to an elevated status of the white working class, at least over black people, which has become a fundamental US value that exists to this day.

A statement made some 300 years later in the 1960s by the 36th President of the USA, Lyndon Baines Johnson, reinforces that argument: ‘I’ll tell you what’s at the bottom of it [racial epithets painted on signs in Tennessee that he had just seen]. If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you’ (Moyers 1988: 1).

So, one of the chief arguments that I make here is that another significant impact of the 1661 slave codes is that it situated black people in two types of US infrastructure: what I call black body infrastructure, an offshoot of the nation’s built infrastructure when slaves were legally identified as property, and a racialized values infrastructure that has been implacably present throughout the USA’s entire history.

Again, Barbados took the lead on the built-infrastructure designation when in 1668 that nation passed An Act Declaring the Negro-Slaves of this Island, to be Real Estate (Hall 1764). With that lawful designation as a piece of real estate, slaves could be inherited just like a house or land or car or boat. Colonial America soon followed. In 1724, a Louisiana law was passed that literally fixed black slaves to the plantations where they resided to make them immovable property (Stewart 1995). Thus, that law made the experience of enslavement a legal component of Louisiana’s built infrastructure.

Regarding a racialized values infrastructure in the USA, the slave codes that became black codes and then Jim Crow laws have all reflected many dehumanizing examples, as explained throughout this paper, of ways to devalue the nation’s black populace. My contention is that those very acts of dehumanization, codified into law, represent a racialized value of foremost significance in the USA, that of black devaluation.

This paper focuses on one consistent method over centuries that has been utilized as a powerful public pedagogical tool, a form of racialized propaganda, to educate and thus frame the derogating identity of black people, as has been described in the laws of the land and promoted by the USA’s values infrastructure. That method has and continues to be racist in the form of cartoons that have been used in commercial as well as political advertisements and artwork that accompanies editorial commentary.in newspapers, often serving ostensibly as comic entertainment.

Part two: politics of a public pedagogy for the oppressed

Michigan’s Ferris State University hosts a Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. This museum lists its extensive collection of cartoons and videos as covering a period from 1877 to 1964. The curator of the Jim Crow Museum, David Pilgrim, tells a powerful tale about how he became a collector of racist memorabilia:

Curator Pilgrim’s belief in the educative potential of his collection to promote tolerance was certainly not present in the intent of the creators of the objects he now has on display. But Pilgrim’s goal for this collection exposes an interesting dialectic. Objects intended to maintain the status quo of black diminishment have now been placed on display to promote tolerance and perhaps some measure of black empowerment. Perhaps. Admittedly, I am not convinced that the curator’s goal will ever become the prevailing outcome for these examples of public pedagogy. In fact, my intent is to reveal what could be considered surprising discoveries: the dehumanizing black imagery created over many years in the USA has not changed much and appears to have spread throughout the world.I am a garbage collector, racist garbage. For three decades I have collected items that defame and belittle Africans and their American descendants. I have a parlor game, ‘72 Pictured Party Stunts,’ from the 1930s. One of the game's cards instructs players to, ‘Go through the motions of a colored boy eating watermelon.’ The card shows a dark black boy, with bulging eyes and blood red lips, eating a watermelon as large as he is. The card offends me, but I collected it and 4,000 similar items that portray blacks as Coons, Toms, Sambos, Mammies, Picaninnies, and other dehumanizing racial caricatures. I collect this garbage because I believe, and know to be true, that items of intolerance can be used to teach tolerance (Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia Website).

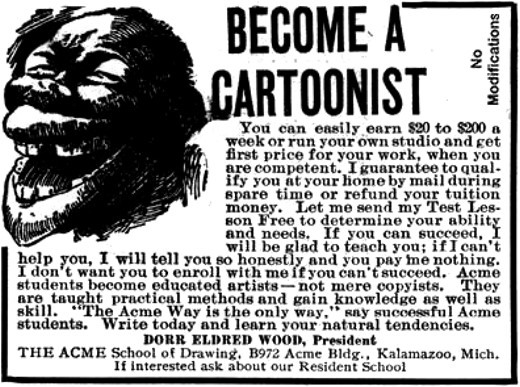

Figure 1 is an advertisement from a classified newspaper in 1917. This Acme School of Drawing promises to train people to become ‘educated artists’ by drawing these types of images to earn $20 to $200 per week. Figure 2 is a poster from a 1937 racist cartoon short. The plot was about black angels looking over black people in Harlem, New York, who are gambling, drinking, and dancing in the streets. The divine solution is to send an angel to Harlem and play such great music the sinners willingly follow the black angel to heaven. The black St Peter in heaven is named ‘Pair-O-Dice’. The image in Figure 3 is from a political cartoon with the title, ‘Please Don’t Go.’ The cartoonist, Clay Jones, was making a positive argument about Barack Obama’s scandal-free presidency and thus not wanting him to leave the White House, so Obama was being dragged by his ankles to stay (The Independent: A Voice for Southern Utah, 11 November 2016). But even with such politically supportive intentions, this image of Obama is unflatteringly racialized.

From Ferris State University Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, circa 1917, a racist magazine advertisement; permission to use granted because of age of image.

From Ferris State University Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, circa 1937, a poster promoting a racist cartoon movie; permission to use granted because of age of image.

From US caricaturist Clay Jones, an image of former President Barack Obama with exaggerated lips, nose, ears, and eyes; permission to use granted by © Clay Jones.

All four of the caricatures of tennis great Serena Williams in Figure 4 depict her as having oversized lips and ape-like features. The cartoon drawn by Mark Knight, and published by The Hill, an online US-based political magazine, generated major controversy because of its blackface minstrelsy-type display of Williams. Knight also posted the image on Twitter for the world to see. Further, it was published on 10 September 2018 in the Herald Sun, a Melbourne, Australia-based publication. What I intend to be notable here is to show that each of the caricatures of Williams was drawn by different artists from around the world—Canada, the USA, Australia, and Spain—within the last ten years. Yet, the images look very much like the racist cartoons from the USA published 100 years ago. Plus, these contemporary cartoons look very much like each other.

From left to right: Serena Williams by cartoonist–artist D. W. Robinson, Canada (n/d website gallery), permission to use granted by © D. W. Robinson; Serena Williams by political cartoonist © Mark Knight, Australia (Twitter, 9 September 2018; The Hill, 25 February 2019), full Twitter image displayed, thus permission to use granted; Serena Williams by caricaturist–cartoonist Taylor Jones, USA (13 September 2011 caglecartoons.com), permission to use granted by © Taylor Jones; Serena Williams by caricature–artist-illustrator Ernesto Priego, Spain (n/d website gallery), permission to use granted by © Ernesto Priego.

My question here is this: how can such similarly drawn racist depictions of a black personality exist across so many national borders? Though this paper’s focus is on the origins and persistence of a racialized US values infrastructure, clearly the nation’s racialized values have been exported, possibly worldwide, showcasing racist imagery of black people. My suspicion would be that this transfer of values-through-imagery has occurred via the USA’s very dominant global entertainment industry.

My political critique of these cartoons as racist memorabilia is that the public pedagogical education factor is not just about an oppressed class of black people, but for—or directed to—an oppressed class of white people. In fact, I contend that a key purpose of racist pedagogical tools, such as editorial cartoons or advertisements, is not to teach black people to embrace the racist imagery of themselves, though black people are certainly impacted in various ways by such disparaging artistic renderings. However, I posit that is not the primary emphasis for such racist propaganda because it is largely assumed by a white mainstream society that black people are in real life very much like the stereotypical images reflected in racist memorabilia. This pejorative view of black people by this white mainstream society is seen as a commonplace cultural truism because of its having been a part of the nation’s racialized values infrastructure for hundreds of years. This belief system was readily revealed by Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney in an excerpt from an infamous 1857 ruling when he wrote: ‘They [Negroes] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect’ (Judgement in the U.S. Supreme Court Case, Record Group 267). So, my argument is that these racist images are intended to mock black people as part of a custom that reinforces for white people that they are superior to the black dehumanized caricatures on display. This also provides some insight into why racist memorabilia or exaggerated caricatured features in black cartoons were—and still are—considered humorous to white people in the USA. The showcasing of dehumanizing images of black people is fun. Still, my contention that racist public pedagogy is not primarily meant to educate black people to accept an inferior status but to uplift white people is, I concede, a counter-intuitive insight that deserves more explanation, and this is provided below (Figure 5).

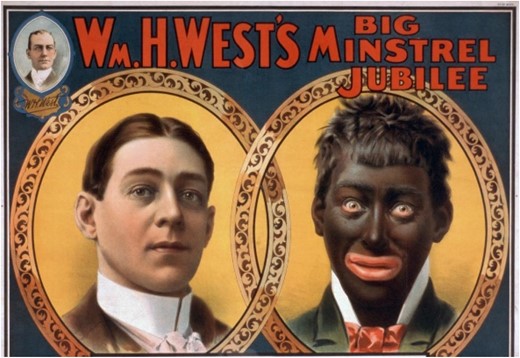

From National Museum of African American History & Culture, Billy Van, a minstrel and monologue comedian, circa 1900; permission to use granted because of age of image. Billy Van, a minstrel and monologue comedian. https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/blackface-birth-american-stereotype

When the Black Slave Codes and white indentured-workers legislation were passed on the same day, 27 September 1661, as mentioned before, the elevation of the white working class over black slaves was firmly ensconced in Barbados law. But in a short period of time, code borrowing by the American colonies led to the same status elevation of white working-class people to ensure that their superiority was established, and that the inferiority of black people was forever maintained. What, then, is an important purpose of racialized public pedagogy? I suggest the purpose was and is to support the confidence of the white working class in the legitimacy of their superiority, not to convince black people of their inferiority. One example of this phenomenon can be found in the performative caricatures of black people put forth by white actors who engaged in the blackface minstrelsy stage productions of the 1800s and early 1900s. Blackface minstrelsy was when both white men and white women smeared black grease paint, shoe polish, or burnt cork on their faces in a way that exaggerated the size of their lips to supposedly look and act like black people while they danced on-stage and sang songs using improper English. Saidiya Hartman, a cultural historian, described blackface performance as the ‘outrageous darky antics of the minstrel stage’ (1997, p. 4). I see the phenomenon of black-minstrelsy entertainment as a live animation or enactment of racialized public pedagogical cartoons. But, as explained by David Roediger, the elaborate face-painting purpose of this form of racialized public pedagogy was a disguise that culturally codified whiteness by demonstrating in a most dramatic fashion that they, the white performers, were not black (2014).

And notwithstanding that most blackface performers were also of a lower socioeconomic class and thus faced class bias by a white upper echelon—and, in the case of white women also faced gender bias in their quest to simply become stage performers—they all still wanted as many as possible of the benefits that were accorded white society, and white supremacy was one such benefit (Roediger 2007; Brooks 2015). Thus, mocking and deriding black society in blackface afforded them the opportunity to have fun on-stage flaunting their supreme white status. In my PhD thesis, I call this phenomenon a type of inverted duality, whereby the white performative debasement of black people is utilized as a tool to reinforce a superior status for white people themselves.

Meanwhile, public pedagogical literature has some relevance for understanding this work, but it is not strictly applicable because it does not acknowledge or recognize some of the damning dialectics involved in public pedagogical practices that impose racist themes. Australian sociologist Glenn Savage’s review of the literature of public pedagogy claims that there are three primary ‘publics’ in that literature—political publics, popular publics, and concrete publics—and that scholars should be mindful of defining not only what is meant by the word ‘pedagogy’, but also what is meant by the word that precedes it, ‘public’ (Savage as cited in Burdick et al. 2013: 80). Savage acknowledges that he relies in part on the ‘publics’’ theorizing of Michael Warner, a professor of English from Rutgers University (2002).

Savage defines political publics as representing a group with a particular polity, an ideology that confines the members of the group to a certain space, such as a nation-state. The weakness of this understanding of public pedagogy, Savage explains, is that it offers a ‘totalizing’ vision of the group itself and does not allow for what Savage refers to as ‘counterpublics’ (p. 84). Counterpublics are the challenges to the group being analysed as ‘unidirectional’ instead of steeped in complexity. Public pedagogy’s involvement in my critique of slave codes and the USA’s racialized values infrastructure is political and complex for reasons other than what Savage describes in his analysis of political publics. My observations support a public pedagogical campaign that serves both the oppressed and the oppressors with the same instructive method because this form of racialized public pedagogy assumes both groups are already in agreement with the message being promulgated, no matter how offensive. The culture of white superiority and black inferiority does not question its belief system, its racialized values infrastructure.

Savage’s description of popular publics is still not a relatable fit for my critique of racialized public pedagogy. The core concern of popular publics, that of articulating a ‘popular vision’ for a large, uncontainable, and hard-to-define public to consume, is antithetical in the case of racialized public pedagogy (p. 86). With racialized public pedagogy, popular publics would only end up applying to one primary audience segment, the oppressor group. This would happen because that same representation of so-called popular vision would be largely unpopular with other audiences, especially those who have been and are still being oppressed by a racialized popular culture’s disparaging message or vision.

Concrete publics, as described by Savage, has at least one interesting connection to those who are oppressed by this form of public pedagogy: the public is in ‘spatially bounded’ environments, which is the norm that certain oppressed communities experience, such as people who live in urban enclaves. This, however, is an area of public pedagogical scholarship that Savage argues has not been sufficiently explored, even by Henry Giroux, a well-known theorist in this field. Still, this is a very complicated category of racialized public pedagogy because, as in the case of black street gangsters, a group that has been oppressed, some of the dehumanizing messaging that has been imposed via racialized public pedagogies on this black gangster class, have been absorbed by them. But then it is reimagined to benefit them, given the particulars of the street culture in which they attempt to thrive. This is a topic examined in my doctoral work and it can lead to very surprising results, such as that gangsters view prison as a good place to end up. This is because the racialized public pedagogical message they have absorbed, which labels them criminal thugs, prompts the gangsters to reinvent themselves into super-gangsters. Super-gangsters go to prison—or ‘gladiator school’—to become even more dangerous, which in that culture is reputationally elevating.

This critique ends by returning the focus to philosopher Charles Mills’ quotation about how epistemologies of ignorance regarding race can lead white society to construct worlds they ultimately do not understand and, worst yet, I argue: they do not understand that they do not understand what they have wrought.

Part three: imagining/reimagining public pedagogical politics of the education academy

My PhD research, which routed me to the Black Slave Codes of 1661 and revealed the significance of how a racialized US values infrastructure was constructed, did demonstrate for me that racism in the USA has in part been carried out by a potent public pedagogical practice. That realization has caused me to raise the question: why has the education academy allowed the theoretical work in this subdiscipline to be so thin, as it was pointed out to me, as mentioned earlier, by a PhD supervisor? Given the role public pedagogy has played in the social construction of racism, this is an important concern.

I do not have answers, but I do have questions to raise and some ideas to share. Why is a classroom or a museum exhibition more important to explore than a public pedagogical campaign, for instance, that can harm or benefit hundreds, thousands, or even millions of people, particularly with the advent of social media? And how might racialized public pedagogy fit into an anti-racist curriculum? There is so much complexity with that subdiscipline, so much to learn about non-classroom learning from studying, for example, how potent racialized public pedagogy has been and can be. So, are education scholars in need of reflexivity work to overcome institutional bias when a subdiscipline does not emerge from traditional pedagogical subject matter? Could the study of racialized public pedagogy itself serve as a reflexive method to shift the epistemic lens of an education scholar? Or is institutional bias provoked by a subject matter, like public pedagogy or racialized public pedagogy, that is prone to be taught by other disciplines, like Media Studies involving film as a form of public pedagogy? Are such topics not held at the same level of esteem in academia?

In conclusion, I suggest that there is something to be learned by education scholars from the black gangster class. The street gangsters have learned how to reimagine themselves for survival. But scholars in education could also consider reimagining themselves so that society can benefit by new insights derived from an important form of education—public pedagogy, especially racialized public pedagogy—one that could use more critical analysis.

References

Footnotes

I am not capitalizing the words ‘black’ or ‘white’ in this paper, but I am capitalizing ‘Negro’ in homage to black scholar W. E. B. Dubois, who launched a letter-writing campaign for years to secure, finally, in 1930, that designation for black people from The New York Times (Coleman 2020). ‘Negro’ is also capitalized here as a proper noun or when quoting someone who has capitalized the word. However, my decolonial ethics do not require me to capitalize ‘black’ and decapitalize ‘white’. I also do not treat those two words in a plural application, such as ‘blacks’ or ‘whites’, unless quoting someone else.

Clause 2 of An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes was transcribed from an image of the handwritten Old English original 1661 document, made accessible to the author on 22 September 2021 by The National Archives, London.