-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nobutaka Takahashi, Toshiyuki Seki, Keita Sasaki, Ryunosuke Machida, Mitsuya Ishikawa, Mayu Yunokawa, Ayumu Matsuoka, Masahiro Kagabu, Satoshi Yamaguchi, Kengo Hiranuma, Junki Ohnishi, Toyomi Sato, High cost of chemotherapy for gynecologic malignancies, Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, Volume 54, Issue 10, October 2024, Pages 1078–1083, https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyae089

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The prognosis of gynecological malignancies has improved with the recent advent of molecularly targeted drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, these drugs are expensive and contribute to the increasing costs of medical care.

The Japanese Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) Health Economics Committee conducted a questionnaire survey of JCOG-affiliated facilities from July 2021 to June 2022 to assess the prevalence of high-cost regimens.

A total of 57 affiliated facilities were surveyed regarding standard regimens for advanced ovarian and cervical cancers for gynecological malignancies. Responses were obtained from 39 facilities (68.4%) regarding ovarian cancer and 37 (64.9%) concerning cervical cancer, with respective case counts of 854 and 163. For ovarian cancer, 505 of 854 patients (59.1%) were treated with regimens that included PARP inhibitors, costing >500 000 Japanese yen monthly, while 111 patients (13.0%) received treatments that included bevacizumab, with costs exceeding 200 000 Japanese yen monthly. These costs are ~20 and ~10 times higher than those of the conventional regimens, respectively. For cervical cancer, 79 patients (48.4%) were treated with bevacizumab regimens costing >200 000 Japanese yen per month, ~10 times the cost of conventional treatments.

In this survey, >70% of patients with ovarian cancer were treated with regimens that included poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors or bevacizumab; ~50% of patients with cervical cancer were treated with regimens containing bevacizumab. These treatments were ~10 and ~20 times more expensive than conventional regimens, respectively. These findings can inform future health economics studies, particularly in assessing cost-effectiveness and related matters.

Introduction

Similar to other carcinomas, chemotherapy is the primary treatment strategy for advanced gynecologic malignancies. Despite treatment advancements, the median survival time for cervical cancer with distant metastasis remains <12 months with cytotoxic combination therapy alone [1]. Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women [2]. Advanced gynecologic malignancies have been treated using platinum-based regimens such as cisplatin [3–5].

Paclitaxel plus carboplatin (TC) therapy has become the standard of care for advanced ovarian cancer since the advent of paclitaxel, remaining unchanged for a long time [6,7]. Following the introduction of bevacizumab (Bev), a molecularly targeted agent, TC plus Bev, and subsequent Bev maintenance therapy, emerged as the next standard of care for advanced ovarian cancer [8,9]. With the introduction of Bev, progression-free survival (PFS) has been extended, although it has not improved overall survival (OS). Furthermore, with the introduction of poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi), PFS has been extended, and TC plus PARPi maintenance therapy has become a new treatment option [10,11]. The advent of PARPi has significantly extended PFS and marginally extended OS (84% vs. 80% at 36 months [10], 84% vs. 77% at 24 months [11]) in the overall population. The current standard chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer is primarily TC plus Bev, followed by Bev maintenance therapy or TC plus PARPi maintenance therapy (Table 1).

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion proportion . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | [11] (2019) | Niraparib 13.8 Placebo 8.2 | Niraparib 84% Placebo 77% (at 24 months) | 177/484 (36.5%) received at data cut off |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | [10] (2018) | Olaparib 56.0 Placebo 13.8 | Olaparib 84% Placebo 80% (at 36 months) | 123/260 (47.3%) completed at the 2-year mark |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | [8,9] (2011) | Bev 14.1 Placebo 10.3 | Bev 39.7 Placebo 39.3 (months) | A median of 16–17 cycles |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | [16] (2019) | Olaparib + Bev 37.2 Placebo 17.7 | Data are immature | 196/537 (36.4%) completed at the 2-year mark |

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion proportion . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | [11] (2019) | Niraparib 13.8 Placebo 8.2 | Niraparib 84% Placebo 77% (at 24 months) | 177/484 (36.5%) received at data cut off |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | [10] (2018) | Olaparib 56.0 Placebo 13.8 | Olaparib 84% Placebo 80% (at 36 months) | 123/260 (47.3%) completed at the 2-year mark |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | [8,9] (2011) | Bev 14.1 Placebo 10.3 | Bev 39.7 Placebo 39.3 (months) | A median of 16–17 cycles |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | [16] (2019) | Olaparib + Bev 37.2 Placebo 17.7 | Data are immature | 196/537 (36.4%) completed at the 2-year mark |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion proportion . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | [11] (2019) | Niraparib 13.8 Placebo 8.2 | Niraparib 84% Placebo 77% (at 24 months) | 177/484 (36.5%) received at data cut off |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | [10] (2018) | Olaparib 56.0 Placebo 13.8 | Olaparib 84% Placebo 80% (at 36 months) | 123/260 (47.3%) completed at the 2-year mark |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | [8,9] (2011) | Bev 14.1 Placebo 10.3 | Bev 39.7 Placebo 39.3 (months) | A median of 16–17 cycles |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | [16] (2019) | Olaparib + Bev 37.2 Placebo 17.7 | Data are immature | 196/537 (36.4%) completed at the 2-year mark |

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion proportion . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | [11] (2019) | Niraparib 13.8 Placebo 8.2 | Niraparib 84% Placebo 77% (at 24 months) | 177/484 (36.5%) received at data cut off |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | [10] (2018) | Olaparib 56.0 Placebo 13.8 | Olaparib 84% Placebo 80% (at 36 months) | 123/260 (47.3%) completed at the 2-year mark |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | [8,9] (2011) | Bev 14.1 Placebo 10.3 | Bev 39.7 Placebo 39.3 (months) | A median of 16–17 cycles |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | [16] (2019) | Olaparib + Bev 37.2 Placebo 17.7 | Data are immature | 196/537 (36.4%) completed at the 2-year mark |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

For advanced cervical cancer, paclitaxel plus cisplatin (TP) therapy has been the standard of care in combination with cytotoxic anticancer agents [12]. Similar to ovarian cancer, TP or TC plus Bev have become the standard of care with the introduction of Bev with the extension of PFS and OS. [13,14] (Table 2). The programmed death receptor (PD)-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab (Pem), an immune checkpoint inhibitor, has been introduced as a new treatment option [15]. The PFS and OS benefit brought about by Bev was further extended by the advent of Pem. The current standard chemotherapy for advanced cervical cancer predominantly involves TP plus Bev and Pem or TC plus Bev and Pem. Notably, Pem was not included in this survey because it was not covered by insurance for cervical cancer until after September 2022.

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion ration . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenancea | [14] (2020) | Bev 10.9 | Bev 25.0 (months, median) | a median of nine cycles |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | [13] (2013) | Bev 8.2 Placebo 5.9 | Bev 17.0 Placebo 13.3 (months) | a median of seven cycles |

| TC or TP + Pem + Bev → Pem + Bev maintenance | [15] (2021) | Pem 10.4 Placebo 8.2 | Pem 50.4% Placebo 40.4% (at 24 months) | a median of 18 cycles |

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion ration . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenancea | [14] (2020) | Bev 10.9 | Bev 25.0 (months, median) | a median of nine cycles |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | [13] (2013) | Bev 8.2 Placebo 5.9 | Bev 17.0 Placebo 13.3 (months) | a median of seven cycles |

| TC or TP + Pem + Bev → Pem + Bev maintenance | [15] (2021) | Pem 10.4 Placebo 8.2 | Pem 50.4% Placebo 40.4% (at 24 months) | a median of 18 cycles |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; TP, paclitaxel + cisplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; Pem, Pembrolizumab; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

aSingle-arm Phase II study.

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion ration . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenancea | [14] (2020) | Bev 10.9 | Bev 25.0 (months, median) | a median of nine cycles |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | [13] (2013) | Bev 8.2 Placebo 5.9 | Bev 17.0 Placebo 13.3 (months) | a median of seven cycles |

| TC or TP + Pem + Bev → Pem + Bev maintenance | [15] (2021) | Pem 10.4 Placebo 8.2 | Pem 50.4% Placebo 40.4% (at 24 months) | a median of 18 cycles |

| Regimen . | Reference number (publication year) . | Main results (median PFS; months) . | Main results (OS) . | Median cycles or dose completion ration . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenancea | [14] (2020) | Bev 10.9 | Bev 25.0 (months, median) | a median of nine cycles |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | [13] (2013) | Bev 8.2 Placebo 5.9 | Bev 17.0 Placebo 13.3 (months) | a median of seven cycles |

| TC or TP + Pem + Bev → Pem + Bev maintenance | [15] (2021) | Pem 10.4 Placebo 8.2 | Pem 50.4% Placebo 40.4% (at 24 months) | a median of 18 cycles |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; TP, paclitaxel + cisplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; Pem, Pembrolizumab; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

aSingle-arm Phase II study.

One challenge posed by advances in the treatment of these cancers is economic toxicity. For example, Bev costs >200 000 Japanese yen (JPY) per month at a standard dosage, whereas PARPi costs >500 000 JPY per month at a standard dosage.

In Japan, the universal health insurance system typically permits the use of expensive drugs, if approved, without special restrictions. However, the pressure on medical costs from these drugs poses a concern, potentially leading to future financial strain on healthcare finances and even bankruptcy [16–18].

In the future, integrating health economic evaluations into clinical research will be crucial to increasing treatment value, managing costs effectively, maintaining treatment quality, and ensuring treatment affordability and sustainability.

Therefore, we conducted a questionnaire survey in Japanese Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG)-affiliated facilities to assess the current status of high-cost medical care in Japan. This study was conducted under the supervision of the JCOG Health Economic Committee.

Materials and methods

We conducted an online questionnaire survey (Google form) of patients with Stages 3 and 4 ovarian cancer and Stage 4b cervical cancer at 57 JCOG-affiliated facilities. Patients targeted for this survey were first diagnosed with advanced ovarian or cervical cancer at JCOG institutions between July 2021 and June 2022. We gathered information on first-line chemotherapy regimens used for each patient without collecting any personal patient data. The number of patients in different age categories (≤74 and ≥75 years) was collected separately. Moreover, costs for supportive care, such as antiemetics or granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), were not included.

For this study, high-cost medical care was defined as >500 000 JPY per month, whereas very high-cost medical care was defined as >1 million JPY per month by the JCOG Health Economics Committee. The personal data of patients were not collected. Thus, this study did not require individual consent or Institutional Review Board approval [19].

Regimens

Ovarian cancer

The regimens studied for advanced ovarian cancer were predetermined as the standard of care before the study began. These regimens were selected by the attending physician based on the patient’s background, including homologous recombination deficiency and breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA) status [10,20], and disease status (e.g. presence of tumor invasion into the intestinal tract).

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin → Niraparib maintenance therapy

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin → Olaparib maintenance therapy

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin + Bevacizumab → Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin + Bevacizumab → Olaparib + Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

The primary results of these regimens in the trials are shown in Table 1.

Cervical cancer

The current standard of care for advanced or recurrent cervical cancer is TC plus Bev plus pembrolizumab; however, pembrolizumab was not covered by insurance until September 2022. As the regimen was not covered by insurance in 2021, the regimens listed below were included in this study.

・Paclitaxel + Cisplatin + Bevacizumab → Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin + Bevacizumab → Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

The primary results of these regimens in the trials are shown in Table 2.

The cost of the regimen was calculated based on a height of 157 cm and weight of 55 kg, with a body surface area of 1.552 m2 [21,22]. The carboplatin dose was calculated using Jelliffe formula at an area under the curve of 5 or 6. The cost of each drug is presented in Table S1.

Calculation of costs of each regimen of ovarian cancer*

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin → Niraparib maintenance therapy

*Paclitaxel(175 mg/m2) + Carboplatin (AUC = 6) → Niraparib × 200 mg daily × 30 days

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin → Olaparib maintenance therapy

* Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) + Carboplatin (AUC = 6) → Olaparib × 600 mg daily × 30 days

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin + Bevacizumab → Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

*Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) + Carboplatin (AUC = 6) + Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks → Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin + Bevacizumab → Olaparib + Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

*Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) + Carboplatin (AUC = 6) + Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks → Olaparib × 600 mg daily × 30 days + Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks

Calculation of costs of each regimen of cervical cancer*

・Paclitaxel + Carboplatin + Bevacizumab → Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

*Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) + Carboplatin (AUC = 5) + Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks → Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks

・Paclitaxel + Cisplatin + Bevacizumab → Bevacizumab maintenance therapy

*Paclitaxel (135 mg/m2) + Cisplatin (50 mg/m2) + Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks → Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks

Results

Questionnaires were distributed to 57 JCOG-affiliated facilities, and responses were received from 39 centers (68.4%) for ovarian cancer and 37 centers (64.9%) for cervical cancer.

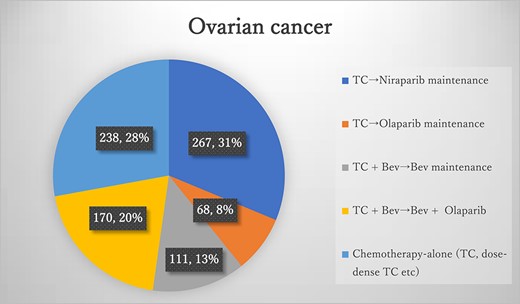

Results of the questionnaires for ovarian cancer TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; Bev, bevacizumab.

The number of patients with ovarian cancer during the study period was 854 (Figure 1), of whom 616 (72.1%, 616/854) were eligible for the study regimen. The most common regimen for ovarian cancer was TC plus niraparib maintenance, involving a total of 267 patients (31%, 267/854). The second most common regimen was TC plus Bev, followed by Bev plus olaparib maintenance, with 170 patients (20%, 170/854). TC plus Bev after Bev maintenance was administered to 111 patients (13%, 111/854). TC plus olaparib maintenance therapy was administered to 68 patients (8%, 68/854). Chemotherapy-alone regimens, including TC and dose-dense TC, were administered to 238 patients (28%, 238/854). Of the 616 patients, 542 (87.9%, 542/616) were under 75 years old, while 74 (12.1%, 74/616) were 75 years or older. Therefore, according to the definition used in this study, 505 patients (59.1%, 505/854) received high-cost medical care as primary therapy. Among the 542 younger patients, 453 (83.5%, 453/542) received high-cost medical care. Among the 72 older patients, 52 (72.2%, 52/72) received high-cost medical care. Regimens containing Bev were 10 times as costly as conventional TC, with no significant OS benefit. Similarly, regimens containing PARPi were 20 times as costly as conventional TC, with no significant OS benefit. The cost of each regimen and its classification as high cost are presented in Table 3.

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | 231 (27%) | 36 (4%) | 267 (31%) | 27 561 → 558 960 |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | 64 (7.5%) | 4 (0.5%) | 68 (8%) | 27 561 → 574 560 |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 89 (10.5%) | 22 (2.5%) | 111 (13%) | 264 222 → 236 661 |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | 158 (18.5%) | 12 (1.5%) | 170 (20%) | 264 222 → 811 221 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 27 561 |

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | 231 (27%) | 36 (4%) | 267 (31%) | 27 561 → 558 960 |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | 64 (7.5%) | 4 (0.5%) | 68 (8%) | 27 561 → 574 560 |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 89 (10.5%) | 22 (2.5%) | 111 (13%) | 264 222 → 236 661 |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | 158 (18.5%) | 12 (1.5%) | 170 (20%) | 264 222 → 811 221 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 27 561 |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; n/s not surveyed.

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | 231 (27%) | 36 (4%) | 267 (31%) | 27 561 → 558 960 |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | 64 (7.5%) | 4 (0.5%) | 68 (8%) | 27 561 → 574 560 |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 89 (10.5%) | 22 (2.5%) | 111 (13%) | 264 222 → 236 661 |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | 158 (18.5%) | 12 (1.5%) | 170 (20%) | 264 222 → 811 221 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 27 561 |

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC → Niraparib maintenance | 231 (27%) | 36 (4%) | 267 (31%) | 27 561 → 558 960 |

| TC → Olaparib maintenance | 64 (7.5%) | 4 (0.5%) | 68 (8%) | 27 561 → 574 560 |

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 89 (10.5%) | 22 (2.5%) | 111 (13%) | 264 222 → 236 661 |

| TC + Bev → Bev + Olaparib maintenance | 158 (18.5%) | 12 (1.5%) | 170 (20%) | 264 222 → 811 221 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 27 561 |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; n/s not surveyed.

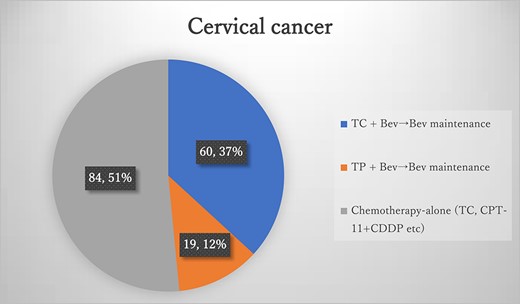

Results of the questionnaires for cervical cancer, TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; TP, paclitaxel + cisplatin; Bev, bevacizumab.

During the study period, 163 patients were diagnosed with cervical cancer (Figure 2), and 79 (49.0%) received the study regimen. The most common regimen for cervical cancer was TC plus Bev, followed by Bev maintenance, with 60 patients (36.8%). TC plus Bev, followed by Bev maintenance, was administered to 19 patients (11.6%). Among these 79 patients, 72 (91.1%, 72/79) were under the age of 75, while seven (8.9%) were over 75. Regimens containing Bev were 10 times as costly as conventional TP or TC, with an OS benefit of several months. The costs of each regimen and their classification as high costs are listed in Table 4.

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 54 (33%) | 6 (4%) | 60 (37%) | 256 974 → 236 661 |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | 18 (11.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 19 (12%) | 254 446 → 236 661 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 24 115 |

| TP | n/s | n/s | n/s | 17 785 |

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 54 (33%) | 6 (4%) | 60 (37%) | 256 974 → 236 661 |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | 18 (11.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 19 (12%) | 254 446 → 236 661 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 24 115 |

| TP | n/s | n/s | n/s | 17 785 |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; TP, paclitaxel + cisplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; n/s not surveyed.

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 54 (33%) | 6 (4%) | 60 (37%) | 256 974 → 236 661 |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | 18 (11.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 19 (12%) | 254 446 → 236 661 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 24 115 |

| TP | n/s | n/s | n/s | 17 785 |

| Treatment . | Age, <75 yr . | Age, >75 yr . | Total . | Cost per month, JPY . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC + Bev → Bev maintenance | 54 (33%) | 6 (4%) | 60 (37%) | 256 974 → 236 661 |

| TP + Bev → Bev maintenance | 18 (11.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 19 (12%) | 254 446 → 236 661 |

| TC | n/s | n/s | n/s | 24 115 |

| TP | n/s | n/s | n/s | 17 785 |

TC, paclitaxel + carboplatin; TP, paclitaxel + cisplatin; Bev, Bevacizumab; n/s not surveyed.

Discussion

Responses were received from 39 out of 57 centers (68.4%) for ovarian cancer and from 37 centers (64.9%) for cervical cancer. For ovarian cancer, high-cost medical care was applicable to 505 (82.1%) of the 615 patients. In addition, 52 (72.2%) received high-cost medical care among the 72 older patients. The trials of PARPi added to chemotherapy alone have shown only marginally prolonged OS (84% vs. 80% at 36 months [10], 84% vs. 77% at 24 months [11]) in the overall population, suggesting that from a cost-effectiveness perspective, the indication of these regimens would be controversial, especially in older patients [10,11].

PARPi introduction has made maintenance therapy with PARPi a standard treatment for ovarian cancer. More cases of TC plus niraparib than TC plus olaparib in this study may be attributed to olaparib being restricted to BRCA-positive patients due to insurance coverage, while niraparib can be used regardless of BRCA status. Considering that the patient was previously monitored only following TC therapy, the introduction of a cytotoxic anticancer drug raised medical costs by ~600 000 JPY per month, potentially for up to 2 or 3 years of maintenance therapy. Prolonged PFS associated with maintenance therapy incurs significant costs [23]. Although the healthcare system differs from that of Japan, generous reimbursement by public insurance could lead to overtreatment and waste of medical resources. High-cost medical care was also provided to patients aged 75 years and older in this study. Considering their prognosis and adverse events, we should consider criteria when administering expensive drugs that allow only a marginal prolongation of OS. The cost of medical care in Japan continues to increase yearly, and measures are required to reduce those costs. The use of biosimilars can be one of those measures [18]. Biosimilars differ from the original drugs, although their clinical efficacy is almost equal to that of the original drugs. They are inexpensive, making them suitable drugs for reducing medical care costs. Biosimilars of Bev have already been used for several carcinomas [24,25].

None of the patients with cervical cancer received high-cost treatments as defined by the JCOG committee, although the regimens were ~200 000 JPY more expensive per month than conventional chemotherapy alone. However, this study excluded patients who received pembrolizumab because it was not covered by insurance in Japan at the time of the study. PD-1 inhibitors, including pembrolizumab, are now indicated for gynecological malignancies, alongside their indications for other cancer types. Four-drug combination therapy consisting of TC plus Bev plus this agent is currently one of the standard treatments for advanced cervical cancer [15]. The estimated cost of this regimen exceeds 600 000 JPY, which corresponds to the high cost of this study (Table S3). Therefore, the proportion of patients receiving high-cost medical care may have increased if this agent was included in the survey.

In cervical cancer, the trial of pembrolizumab added to chemotherapy alone has shown prolonged OS (50.4% vs. 40.4% at 24 months), suggesting that from a cost-effectiveness perspective, these regimens’ indication in all patients, including older patients, is controversial. The use of Bev biosimilar in ovarian cancer is also expected to reduce costs; therefore, the development of biosimilars for PD-1 inhibitors and PARPi is expected to advance.

The standard treatments of gynecological cancers are decided by PFS elongation, and thus include drugs without OS benefit (Bev for ovarian cancer) or with OS benefit with only marginal OS benefit (PARPi for ovarian cancer). These drugs, however, bring a 10- to 20-fold increase in treatment costs, questioning the sustainability of cancer care.

This study had several limitations. This survey was conducted over a limited period at JCOG-affiliated facilities. Individual patient data were not collected; therefore, the actual dosing periods, drug discontinuations, or dose reduction could not be considered. In addition, they were not evaluated using measures such as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of the most recent PAPRi and ICI treatment regimens.

Conclusion

More than 70% of patients with ovarian cancer received regimens containing PARP inhibitors or Bev, and ~50% of patients with cervical cancer received regimens containing Bev, which were ~10 or ~20 times more expensive than conventional regimens, respectively. Japanese patients with gynecological cancers receive state-of-the-art therapies, but the associated costs have increased substantially. The results of this study may be used in future health economics studies examining cost-effectiveness and other issues.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Fund of the National Federation of Health Insurance Societies (Kenpo-ren) and the National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds ( 2023-J-03).

References

- adenosine

- carcinoma

- chemotherapy regimen

- cervical cancer

- cost effectiveness

- carboplatin

- diphosphates

- medical economics

- health care costs

- medical oncology

- poly(adp-ribose) polymerases

- ribose

- ovarian cancer

- bevacizumab

- gynecologic cancer

- gynecological oncology

- poly(adp-ribose) polymerase inhibitors

- molecular targeted therapy

- japanese

- immune checkpoint inhibitors