-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kunihiro Ikuta, Yoshihiro Nishida, Shiro Imagama, Kazuhiro Tanaka, Toshifumi Ozaki, The current management of clear cell sarcoma, Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, Volume 53, Issue 10, October 2023, Pages 899–904, https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyad083

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Clear cell sarcoma (CCS) is a rare melanocytic soft tissue sarcoma with a high propensity for lymphatic metastasis and poor prognosis. It is characterized by the translocation of t (12;22), resulting in the rearrangement of the EWSR1 gene and overexpression of MET. Despite improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of soft tissue sarcomas, the management of CCSs remains challenging owing to their rarity, unique biological behaviour and limited understanding of their molecular pathogenesis. The standard treatment for localized CCSs is surgical excision with negative margins. However, there is an ongoing debate regarding the role of adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy and lymphadenectomy in the management of this disease. CCSs are usually resistant to conventional chemotherapy. Targeted therapies, such as sunitinib and MET inhibitors, may provide promising results. Immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors, is currently under investigation as a potential treatment option for CCSs. Further research is needed to better understand the biology of CCSs and develop effective therapeutic strategies. The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of current knowledge and advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CCSs.

Introduction

Clear cell sarcoma (CCS) is extremely rare, accounting for ˂1% of all soft tissue sarcomas, with an incidence of ⁓1 per million per year (1–4). It was first described by Enzinger et al. as a soft tissue tumour with melanocytic differentiation in 1965 and was thereafter described as a malignant melanoma of the soft parts (5–7). However, despite sharing morphological similarities with malignant melanoma, CCS is a clinically and biologically distinct entity (8–10).

CCS primarily affects young adults aged 20–40 years and typically involves the lower extremities, particularly in the tendons and aponeuroses of the feet and ankle joints (10–12). However, rare cases have been reported in other areas, such as the kidney, trunk, penis, gastrointestinal tract, head and neck (12–16). Racial differences have been observed in the frequency of occurrence, with CCS being more common in Caucasians than in Asians or African Americans (2,17). Tumours grow slowly and can be mistaken for benign lesions, often requiring several years from their appearance to diagnosis (5,11,18,19). Patients often undergo unplanned excision of lesions and are subsequently referred to a sarcoma specialist (1,20).

In contrast, ⁓30% of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease at diagnosis (19,20). Even with optimal surgical treatment, a high proportion of patients will relapse, indicating the aggressive nature of CCS (1,18–20). CCS is typically resistant to conventional anthracycline-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy (19,21). A review of the literature shows that the prognosis for CCS patients is dismal (Table 1). Overall survival rates range from 47 to 67% at 5 years but decrease to 20% in patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis (1,2,4,8,10,18,19,22). Distant metastases most frequently involve the lungs and bones followed by distant lymph nodes (2,18,22). Long-term follow-up is required because late local recurrence and distant metastasis are not uncommon (1,8–11,19). This review provides a comprehensive overview of the current knowledge and advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CCS.

| Authors (ref) . | Year . | No. of patients . | 5-year survival rate . | Distant metastasis . | Lymph node metastasis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chung et al. (7) | 1983 | 141 | NA | 50% | NA |

| Lucas et al. (22) | 1992 | 35 | 67% | 63% | 34% |

| Deenik et al. (18) | 1999 | 30 | 54% | 60% | 43% |

| Ferrari et al. (8) | 2002 | 28 | 66% | NA | NA |

| Kawai et al. (19) | 2007 | 75 | 47% | 5-year rate: 61%a | NA |

| Hisaoka et al. (24) | 2008 | 33 | 63% | NA | NA |

| Clark et al. (1) | 2008 | 72 | 52% | 40% | 20% |

| Blazer et al. (4) | 2009 | 182 | 64% | NA | 18% |

| Hocar et al. (10) | 2012 | 52 | 59% | 5-year rate: 43% | 5-year rate: 34% |

| Bianchi et al. (20) | 2014 | 31 | 56% | 30% for localized disease | 13% for localized disease |

| Gonzaga et al. (2) | 2018 | 489 | 50% | NA | NA |

| Authors (ref) . | Year . | No. of patients . | 5-year survival rate . | Distant metastasis . | Lymph node metastasis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chung et al. (7) | 1983 | 141 | NA | 50% | NA |

| Lucas et al. (22) | 1992 | 35 | 67% | 63% | 34% |

| Deenik et al. (18) | 1999 | 30 | 54% | 60% | 43% |

| Ferrari et al. (8) | 2002 | 28 | 66% | NA | NA |

| Kawai et al. (19) | 2007 | 75 | 47% | 5-year rate: 61%a | NA |

| Hisaoka et al. (24) | 2008 | 33 | 63% | NA | NA |

| Clark et al. (1) | 2008 | 72 | 52% | 40% | 20% |

| Blazer et al. (4) | 2009 | 182 | 64% | NA | 18% |

| Hocar et al. (10) | 2012 | 52 | 59% | 5-year rate: 43% | 5-year rate: 34% |

| Bianchi et al. (20) | 2014 | 31 | 56% | 30% for localized disease | 13% for localized disease |

| Gonzaga et al. (2) | 2018 | 489 | 50% | NA | NA |

Ref: reference, NA: not available.

aIncluding lymph node metastasis.

| Authors (ref) . | Year . | No. of patients . | 5-year survival rate . | Distant metastasis . | Lymph node metastasis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chung et al. (7) | 1983 | 141 | NA | 50% | NA |

| Lucas et al. (22) | 1992 | 35 | 67% | 63% | 34% |

| Deenik et al. (18) | 1999 | 30 | 54% | 60% | 43% |

| Ferrari et al. (8) | 2002 | 28 | 66% | NA | NA |

| Kawai et al. (19) | 2007 | 75 | 47% | 5-year rate: 61%a | NA |

| Hisaoka et al. (24) | 2008 | 33 | 63% | NA | NA |

| Clark et al. (1) | 2008 | 72 | 52% | 40% | 20% |

| Blazer et al. (4) | 2009 | 182 | 64% | NA | 18% |

| Hocar et al. (10) | 2012 | 52 | 59% | 5-year rate: 43% | 5-year rate: 34% |

| Bianchi et al. (20) | 2014 | 31 | 56% | 30% for localized disease | 13% for localized disease |

| Gonzaga et al. (2) | 2018 | 489 | 50% | NA | NA |

| Authors (ref) . | Year . | No. of patients . | 5-year survival rate . | Distant metastasis . | Lymph node metastasis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chung et al. (7) | 1983 | 141 | NA | 50% | NA |

| Lucas et al. (22) | 1992 | 35 | 67% | 63% | 34% |

| Deenik et al. (18) | 1999 | 30 | 54% | 60% | 43% |

| Ferrari et al. (8) | 2002 | 28 | 66% | NA | NA |

| Kawai et al. (19) | 2007 | 75 | 47% | 5-year rate: 61%a | NA |

| Hisaoka et al. (24) | 2008 | 33 | 63% | NA | NA |

| Clark et al. (1) | 2008 | 72 | 52% | 40% | 20% |

| Blazer et al. (4) | 2009 | 182 | 64% | NA | 18% |

| Hocar et al. (10) | 2012 | 52 | 59% | 5-year rate: 43% | 5-year rate: 34% |

| Bianchi et al. (20) | 2014 | 31 | 56% | 30% for localized disease | 13% for localized disease |

| Gonzaga et al. (2) | 2018 | 489 | 50% | NA | NA |

Ref: reference, NA: not available.

aIncluding lymph node metastasis.

Diagnosis

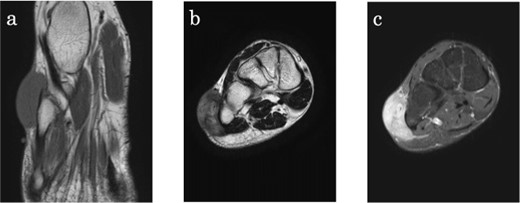

The diagnosis of CCS is challenging because of its rarity and the lack of specific clinical and radiological features. The clinical manifestations of CCS vary, with masses ranging from being asymptomatic to painful and tender. In most cases, CCS does not cause symptoms until it progresses. Accurate diagnosis depends on the level of experience of the physician at presentation, and prompt referral to a specialized institution is essential (17). CCS is typically diagnosed through a combination of physical examinations and imaging studies, such as plain radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography and histological examination. On MRI, CCS is often depicted as a homogeneous and well-defined mass with slightly increased signal intensity compared with muscle on T1-weighted images, and as a heterogeneous mass with variable signal intensity on T2-weighted images (3) (Fig. 1). However, these findings are nonspecific and do not enable the use of MRI to diagnose CCS (12,23). Biopsy involves obtaining a tissue sample from the tumour and examining it under a microscope to identify the presence of clear cells and other diagnostic features. As CCS can metastasize hematogenously or via the lymphatic system, preoperative check-ups with whole-body CT, positron emission tomography or bone scintigraphy are often required for staging (17,19).

Clear cell sarcoma on the lateral aspect of the right foot in a 34-year-old male. (a) Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image shows a lesion with slightly higher signal intensity compared with skeletal muscle. (b) Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows the tumour with high signal intensity, adjacent to the bone, and extending into the subcutis. (c) On T1-fat suppressed coronall MR image, the lesion is homogenously enhanced with gadolinium.

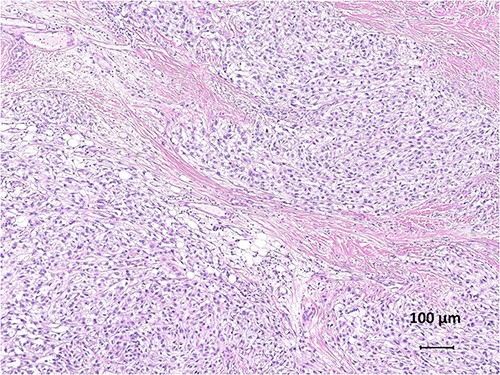

Histologically, CCS is characterized by spindle-to-polygonal cells arranged in fascicles or nests with a clear cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (1,6,22) (Fig. 2). The clear cell appearance is due to the accumulation of glycogen (23). The tumour cells are relatively uniform and surrounded by reticulate stroma and scattered multinucleated giant cells (10,22). Tumour cells usually do not have pleomorphic figures and mitotic figures are scarce, consistent with the slow growth of CCS (7,23). However, CCS is not officially graded in the French Federation of Cancer Centres’ grading system for soft tissue sarcomas but should be considered ‘high grade’ in staging and treatment (9). Immunohistochemical staining is generally positive for S100 protein and melanocyte-specific markers, such as HMB-45 and Melan-A, similar to melanoma tumour cells (3,10,20,24–26). The expression of epithelial markers, including cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen, was positive, whereas that of keratin, smooth muscle actin and desmin was negative in CCS specimens (20,23,24).

Histological findings of clear cell sarcoma. Tumour cells with abundant cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli are separated into nests by fibrous septa (haematoxylin and eosin, ×100).

CCS is a translocation-associated sarcoma. Fluorescence in situ hybridization or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction is useful for confirming CCS and differentiating it from malignant melanomas. CCS harbours either a t(12;22)(q13;q12) recurrent translocation, resulting in an EWSR1/ATF1 chimeric gene or less commonly a t(2;22)(q34;q12) translocation fusing EWSR1 and CREB1 (24,25,27). The EWSR1/ATF1 fusion gene is common and is presented in 70–90% of CCS cases (6). EWSR1/ATF1 activates microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), which is expressed positively in 81–97% of CCS samples (10,24). MITF in turn upregulates mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (MET), an oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase (28). MET mediates signalling from hepatocyte growth factor and promotes tumour cell growth, survival and invasion in CCS (21,28,29). However, neither translocations of EWSR1/ATF1 nor EWSR1/CREB1 have been previously reported in malignant melanomas (26). No association between the type of fusion gene and clinical outcomes has been demonstrated (19,26,30).

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of CCS includes neoplasms that are positive for S100 protein and/or melanocyte markers, such as malignant melanoma, epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours, melanotic schwannomas and perivascular epithelioid cell tumours. Other tumours, such as synovial sarcoma, alveolar soft part sarcoma, paraganglioma, epithelioid sarcoma and carcinoma, may also need to be considered (9,23). Malignant melanoma is a common differential diagnosis of CCS; however, unlike CCS, it usually occurs in the older adults and involves the epidermal component (23). CCS occasionally lacks the melanin pigment characteristics of malignant melanoma and does not show as much nuclear pleomorphism or mitotic activity as malignant melanoma (1,6). However, differentiating metastatic melanoma of unknown primary origin from CCS can be complicated, because both tumours have similar histological features and immunohistochemical findings. The most significant difference was the presence of the t(12;22) translocation in CCS, which was not observed in malignant melanoma.

Treatment

Surgical excision

The standard treatment for localized CCS is a wide surgical excision with negative margins. Implementation of multidisciplinary therapy varies according to the policies of each institution. However, the roles of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy have not yet been established. (10,20,23). Adjuvant therapy is not usually indicated when a tumour can be excised with an R0 margin (8,19,23). Tumour excision with R1 and R2 margins was associated with a significantly worse prognosis (19). However, even with optimal surgical treatment, ⁓50% of patients relapse, indicating the aggressive nature of CCS (20). Therefore, the role of surgery in managing metastatic disease is limited and surgical treatment is typically reserved for palliative purposes to relieve symptoms.

Lymph nodes dissection

CCS has a high propensity for lymphatic metastasis (5,7,31) (Table 1). Lymph node metastases can be found in 6–23% of patients at diagnosis (2,8,19,20,22). Lymph node metastasis was the most common pattern of first recurrence (31). Up to 40% of patients developed metastatic disease in the lymph nodes (1,4,10,18–20). When lymph node metastasis is suspected, most surgeons perform lymph node dissection during the initial surgery (32,33). Some authors advocate prophylactic selective lymph node dissection, whereas others suggest performing lymph node dissection only in patients presenting with clinical lymphadenopathy (8,19,33). Given the risk of regional lymph node metastasis in CCS, there has been interest in performing sentinel node biopsy, which may allow earlier detection of lymph node metastases and improve patient prognosis (20,31). Although some reports indicate the usefulness of sentinel node biopsy in CCS, there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations (9,11,12,19,23,33,34). Additionally, the prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis in CCS is uncertain, with some studies suggesting that it may not significantly impact overall survival (19,20). Therefore, the role of lymph node dissection in the surgical management of CCS remains controversial. Although adequately powered clinical trials are not feasible due to the rarity of CCS, there needs to be a consensus on the optimal surgical approach.

Radiation therapy

CCS is generally considered to have low radiation sensitivity. With no consensus guidelines, adjuvant radiation therapy for CCS can be both institutional- and surgeon-dependent. Adjuvant radiotherapy may improve the survival of patients with close or positive margins after surgery (18,23). However, several studies have shown no survival advantage in patients with CCS receiving adjuvant radiotherapy (1,19). It remains unclear whether radiation therapy confers survival advantages.

Chemotherapy

Adjuvant setting

CCS is commonly recognized to be resistant to chemotherapy. Several authors suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy is not necessary if adequate margins are obtained by surgical excision (8,17). However, information on how this disease responds to cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, such as doxorubicin and ifosfamide, is scarce. Therefore, there is still a consensus regarding its use in adjuvant settings.

Palliative setting

Despite optimal management of localized disease, a high proportion of patients develop metastatic disease (1,18–20). Although chemotherapy is primarily used in patients with metastatic disease, the treatment of advanced CCS remains challenging due to the lack of an established standard systemic therapy. Anthracyclines are widely administered to metastatic CCS, with a few reporting partial responses (4%) (21). However, other reports have not demonstrated the efficacy of anthracycline-based chemotherapy (8,18). Kawai et al. reported partial responses in seven of 30 patients who received chemotherapy, albeit with various regimens, suggesting some degree of chemosensitivity to CCS (19). They also suggested that caffeine-assisted chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin might offer the potential for a tumour response. Fujimoto et al. reported a case of metastatic CCS with complete remission following combined chemotherapy with dacarbazine, nimustine and vincristine, which is used for malignant melanoma (35).

In contrast, Jones et al. reported a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 11 weeks following first-line palliative treatment and showed no effect of platinum-based chemotherapy on tumour response (21). In a retrospective study of 55 patients with locally advanced or metastatic CCS, Smrke et al. concluded that systemic therapy for CCS had limited benefits, with a median PFS of 2 months (36). These previous studies suggest that alternative strategies are required for the systemic therapy of CCS.

Targeted therapy

Recently, molecular targeted therapies have been developed for the treatment of patients with CCS (Table 2). Identifying the characteristic EWSR1-ATF1 gene fusion in CCS has led to the development of targeted therapies, such as MET inhibitors.

| Treatment (ref) . | Patients . | Outcome (n) . | Median PFS (month) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunitinib (36) | 10 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (3), SD (2), PD (4), NE (1) | 4 |

| Pazopanib (36) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (0), SD (3), PD (9), NE (4) | 1 |

| Nivolumab plus sunitinib (IMMUNOSARC phase 1) (45) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic sarcoma (including four CCS) | PR (2), NA (2) | NA |

| Crizotinib (37) | 28 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | One PR in the 26 evaluable pts | 4.3 |

| Tivantinib (29) | 47 pts with metastatic or unresectable sarcoma (including 11 CCS) | PR (1), SD (3), PD (6), NE (1) | 1.9 |

| Treatment (ref) . | Patients . | Outcome (n) . | Median PFS (month) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunitinib (36) | 10 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (3), SD (2), PD (4), NE (1) | 4 |

| Pazopanib (36) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (0), SD (3), PD (9), NE (4) | 1 |

| Nivolumab plus sunitinib (IMMUNOSARC phase 1) (45) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic sarcoma (including four CCS) | PR (2), NA (2) | NA |

| Crizotinib (37) | 28 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | One PR in the 26 evaluable pts | 4.3 |

| Tivantinib (29) | 47 pts with metastatic or unresectable sarcoma (including 11 CCS) | PR (1), SD (3), PD (6), NE (1) | 1.9 |

Ref: reference, pts: patients, PFS: progression-free survival, CCS: clear cell sarcoma, PR: partial response, SD: stable disease, PD: progressive disease, NE: not evaluated, NA: not available.

| Treatment (ref) . | Patients . | Outcome (n) . | Median PFS (month) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunitinib (36) | 10 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (3), SD (2), PD (4), NE (1) | 4 |

| Pazopanib (36) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (0), SD (3), PD (9), NE (4) | 1 |

| Nivolumab plus sunitinib (IMMUNOSARC phase 1) (45) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic sarcoma (including four CCS) | PR (2), NA (2) | NA |

| Crizotinib (37) | 28 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | One PR in the 26 evaluable pts | 4.3 |

| Tivantinib (29) | 47 pts with metastatic or unresectable sarcoma (including 11 CCS) | PR (1), SD (3), PD (6), NE (1) | 1.9 |

| Treatment (ref) . | Patients . | Outcome (n) . | Median PFS (month) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunitinib (36) | 10 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (3), SD (2), PD (4), NE (1) | 4 |

| Pazopanib (36) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | PR (0), SD (3), PD (9), NE (4) | 1 |

| Nivolumab plus sunitinib (IMMUNOSARC phase 1) (45) | 16 pts with locally advanced or metastatic sarcoma (including four CCS) | PR (2), NA (2) | NA |

| Crizotinib (37) | 28 pts with locally advanced or metastatic CCS | One PR in the 26 evaluable pts | 4.3 |

| Tivantinib (29) | 47 pts with metastatic or unresectable sarcoma (including 11 CCS) | PR (1), SD (3), PD (6), NE (1) | 1.9 |

Ref: reference, pts: patients, PFS: progression-free survival, CCS: clear cell sarcoma, PR: partial response, SD: stable disease, PD: progressive disease, NE: not evaluated, NA: not available.

The efficacy of crizotinib, a MET tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), was evaluated in a phase 2 study (CREATE) for MET-positive, locally advanced or metastatic CCS (37). The study showed that crizotinib provided some clinical benefits; however, it did not meet its primary endpoint (overall response rate), as only one partial response was observed amongst the 26 evaluable patients. Tivantinib, another selective MET inhibitor, was administered to 11 patients with CCS in a phase 2 study (NCT00557609) (29). This trial described a partial response in one of 11 patients (9%), with a median PFS of 1.9 months. QUILT-3.031, a phase 2 single-arm study, evaluated the primary endpoint of the efficacy of AMG 337 (an oral MET inhibitor) in advanced or metastatic CCS with EWSR1-ATF1 gene fusion (NCT03132155) (38). However, this trial was terminated prematurely because of lack of therapeutic efficacy. Although CCS oncogenesis has been studied, its clinical effects in patients with advanced CCS are yet to be elucidated. These studies imply that additional factors may play a role in the oncogenesis and advancement of CCS, in addition to the upregulation of MET.

Several retrospective studies have suggested modest activity of TKI, such as sorafenib and sunitinib, in patients with CCS (36,39–41). Smrke et al. reported that in patients with locally advanced or metastatic CCS, 30% of those treated with sunitinib showed a partial response (36). In contrast, none of the patients treated with pazopanib exhibited an objective response (36,41). Although further prospective evaluation is needed, they suggest that sunitinib is useful as a first-line therapy in this disease if no clinical trial is available. Additionally, several case reports described patients with metastatic CCS treated with sunitinib who achieved a partial response (40,42). Mir et al. reported tumour shrinkage and a progression-free period of 8.2 months in a patient with metastatic CCS treated with sorafenib (39). Although the activity of pazopanib has not been reported, these findings suggest that TKI targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptorshould be investigated further as treatment options for this disease.

Immunotherapy

There is growing interest in exploring the potential of immune checkpoint inhibition in the treatment of CCS. Pembrolizumab was reported to be effective in a relapsed case with CCS (43). Similar to malignant melanoma, CCS is associated with MITF expression, which is involved in tumour growth. Because these diseases have been suggested to share similarities in host immune reactivity to tumours, nivolumab is expected to be a promising treatment for CCS as well as malignant melanoma, where nivolumab is effective (42). The preliminary results of the phase 2 OSCAR study evaluated the potential of nivolumab in a cohort of 11 patients with advanced CCS and 14 with alveolar soft part sarcoma (UMIN000023665) (44). Although the response rate was 7.1% and the primary endpoint was not met, the trial achieved a disease control rate of 64% and a median PFS of 4.9 months. Additionally, immunotherapy may offer a novel therapeutic option for patients with advanced CCS in association with molecular targeted therapies. The IMMUNOSARC study is a 1/2 phase study that evaluated the efficacy of the combination of sunitinib and nivolumab in selected bone and soft tissue sarcomas with unresectable or metastatic disease (NCT03277924) (45). The study included four and seven CCS in phase 1 and 2, respectively. The study demonstrated a partial response in 2 (50%) CCS in phase 1.

Survival

Patients with recurrent or regional lymph node metastases eventually develop distant metastases, requiring local disease control and long-term surveillance (11). Previous studies have shown that overall survival rates range from 47 to 67% and 25 to 41% at 5 and 10 years, respectively (1,2,4,8,10,18,19,22). In patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, the median overall survival was 10–15 months (21,36). Previous studies demonstrated that clinical variables, including tumour sizes greater than 4–5 cm, the presence of metastatic disease, non-Caucasian ethnicity, the presence of necrosis and location in the trunk, were unfavourable prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis (1,4,10,19,20,22). Prognostic value was not found for the type of fusion variant or transcript (19,26,30).

Ongoing clinical trials

Clinical trials in CCS have mainly focused on TKI and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). Two phase 2 trials with dostarlimab (NCT04274023) and atezolizumab (NCT04458922) are currently underway, with expected results by 2024 (46,47). The results of these trials are eagerly awaited to further define the role of ICI in this population. Patients with relapsed or refractory CCS were recruited for a phase 1/2 study using devimistat in combination with hydroxychloroquine (NCT04593758) (36,48). Devimistat has been shown to synergize with low-dose chemotherapy to improve the therapeutic benefits in patients. This agent increases cellular stress by targeting mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid, a process through which tumour cells can multiply. The estimated study completion date was 2024.

Conclusion

Although there is no consensus on the roles of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy, they are unlikely to be promising treatments for CCS. In clinical development, the rarity of CCS makes it difficult to conduct large prospective studies. In this context, the development of novel therapeutic approaches, such as ICI and molecular targeted therapies, is a promising step towards improving the survival of patients with CCS. Sustained collaboration between clinicians, researchers and patients is essential to improve the management of CCS.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this study.