-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hiroshi Kitamura, Shiro Hinotsu, Taiji Tsukamoto, Taro Shibata, Junki Mizusawa, Takashi Kobayashi, Makito Miyake, Naotaka Nishiyama, Takahiro Kojima, Hiroyuki Nishiyama, Urologic Oncology Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group, Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on health-related quality of life in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results from JCOG0209, a randomized phase III study, Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, Volume 50, Issue 12, December 2020, Pages 1464–1469, https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyaa123

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy provides survival benefits in muscle-invasive bladder cancer, the impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on health-related quality of life has not been investigated by a randomized trial. The purpose of this study is to compare health-related quality of life in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy or radical cystectomy alone based on patient-reported outcome data.

Patients were randomized to receive two cycles of neoadjuvant methotrexate, doxorubicin, vinblastine, and cisplatin followed by radical cystectomy or radical cystectomy alone. Health-related quality of life was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bladder (version 4) questionnaire before the protocol treatments, after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, after radical cystectomy and 1 year after registration.

A total of 99 patients were analysed. No statistically significant differences in postoperative health-related quality of life were found between the arms. In the neoadjuvant chemotherapy arm, the scores after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were significantly lower than the baseline scores in physical well-being, functional well-being, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General total, weight loss, diarrhoea, appetite, body appearance, embarrassment by ostomy appliance and total Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bladder. However, there was no difference in scores for these domains, except for embarrassment by ostomy appliance, between the two arms after radical cystectomy and 1 year after registration.

Although health-related quality of life declined during neoadjuvant chemotherapy, no negative effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on health-related quality of life was apparent after radical cystectomy. These data support the view that neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be considered as a standard of care for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer regarding health-related quality of life.

Introduction

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is potentially associated with progression to metastasis and unfavourable prognosis despite optimal treatment (1). Radical cystectomy (RC) has been the gold standard of MIBC treatment for the last three decades. Although RC provides excellent local control, survival depends on the pathological tumour stage: Five-year overall survival (OS) estimates range from 81–93% for patients with pT0/a/is/1 disease to 46–48% for patients with pT3 disease (2–4).

The data support the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) followed by RC for T2-T4aN0M0 MIBC (5–8). The Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) 0209 trial compared methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC)-based NAC followed by RC with RC alone in patients with clinical T2-T4aN0M0 bladder cancer (9), demonstrating not only the favourable OS and progression-free survival (PFS) of patients who received neoadjuvant MVAC, but also the tolerability and lack of surgical delay associated to this treatment. Although emerging results of clinical trials for NAC with immune checkpoint inhibitors have appeared (10), neoadjuvant MVAC can still be considered promising as a standard treatment.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is compromized in all advanced cancer patients (11). RC is a major operation in which reduction of morbidity, rapid postoperative rehabilitation, limited length of hospital stay and cost containment are difficult to achieve (12,13). NAC may also have a profound effect on HRQoL due to haematological and/or non-haematological toxicities. However, most of the literature related to HRQoL in bladder cancer has focused on the differences between the types of urinary diversion after RC, and is retrospective in nature (14–17). Only one study (18) reported the HRQoL during neoadjuvant gemcitabine+cisplatin or gemcitabine+carboplatin. However, this study included both bladder and upper tract urothelial cancer patients, and terminated the HRQoL assessment at the end of NAC, meaning that no QoL data after RC or comparisons with patients undergoing RC alone were presented.

The JCOG0209 included secondary endpoints involving patient-reported outcomes (PROs) on HRQoL using tools such as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bladder (FACT-BL), a reliable and validated multidimensional disease-specific tool for assessing HRQoL in bladder cancer patients.

In this study, we investigated the effect of NAC on HRQoL after RC by comparing patients who underwent NAC plus RC or RC alone. We assumed that NAC impairs postoperative HRQoL due to its toxicities, and that NAC increases HRQoL through the relief of disease-related symptoms or disease control in the long term. Furthermore, the longitudinal change of HRQoL in patients who received NAC was examined.

Patients and methods

Study design and treatment

This randomized trial has been reported previously (9), to which we refer for details about chemotherapy and RC. Briefly, patients with T2-4aN0M0 (6th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control TNM cancer staging) urothelial carcinoma (UC) of the bladder were randomized between two cycles of neoadjuvant MVAC followed by RC and RC alone.

The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the JCOG Protocol Review Committee in January 2002, and by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. All patients provided written informed consent. This trial is registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry, number C000000093.

Outcome

The primary endpoint was overall survival. Secondary endpoints were PFS, surgery-related complications, adverse events (AEs) during chemotherapy, proportion with no residual tumour (pT0) and HRQoL. In this article, we report the results concerning HRQoL.

HRQoL measurement

HRQoL was assessed by the Japanese edition of the FACT–BL, which was established and validated (19) in patients with advanced UC and shown to be consistent with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines for PRO validation. FACT-BL is a multidimensional, PRO questionnaire with 39 items, using a core set of questions [Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G); includes the four domains of physical, social/family, emotional and functional well-being] and a bladder cancer-specific subscale composed of 13 items related to urinary issues, bowel issues, appetite, weight loss, sexual issues, body image and ostomy appliances. Each item has five possible responses.

The questionnaire was translated into Japanese (20) and tested by studies mostly assessing HRQoL in patients with bladder cancer who underwent urinary diversion (21). HRQoL was assessed before treatment, after chemotherapy (only for the NAC arm; post-NAC), 6 to 8 weeks after cystectomy (post-RC), and 1 year after randomization (1Y). Paper-based questionnaires were given to the patients, who filled them and returned them by mail. The items were scaled and calculated according to the scoring and interpretation manual, and transformed into a scale of 0–100 points.

Statistical analyses

The sample size planned based on power calculations was 360 patients. The protocol was amended to continue patient accrual until either 6 years after the accrual start or until 150 patients were enrolled.

Power calculation for HRQoL was not performed. All randomized patients with HRQoL data before treatment were analysed. Multiplicity adjustment was not conducted because of the exploratory nature of the analysis. Missing data, except at baseline, were imputed with worst scores (22). The change from baseline to each assessed point was calculated per patient, and comparisons between arms at post-RC and 1 year were performed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. In the NAC arm, the change from baseline to post-NAC was tested using the one-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test. All other P values were two-sided, and the significance threshold was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS, version 9.2 or later (SAS Institute, Inc.).

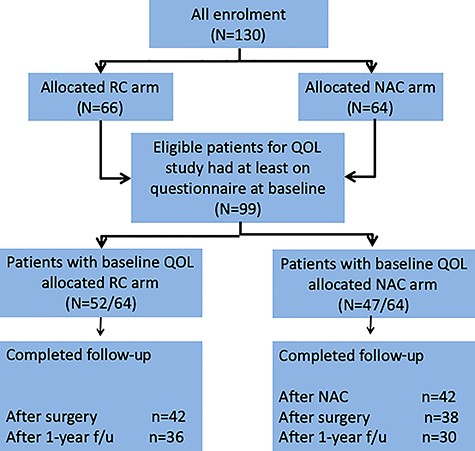

Results

Of the 130 randomly assigned patients, 99 who had returned the questionnaire at baseline were included in the analysis. Of the 66 patients allocated to the RC arm, 52 (78.8%) returned the baseline questionnaire, and 42 (63.6%) and 36 (54.5%) were completely followed up after RC and 1 year after registration, respectively. Of the 64 patients allocated the NAC arm, 47 (73.4%) returned the baseline questionnaire, and 42 (65.6%), 38 (59.4%) and 30 (46.9%) were completely followed up after NAC, after RC and 1 year after registration, respectively (Fig. 1). A total of 923 (5.8%) of 15 840 data were missing. The patients’ characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

| Characteristics . | RC arm (N = 52) . | NAC arm (N = 47) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 63 | 63 |

| ≤60 | 18 (34.6%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| ≥61 | 34 (65.3%) | 25 (53.2%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48 (92.3%) | 41 (87.2%) |

| Female | 4 (7.7%) | 6 (12.8%) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 51 (98.1%) | 46 (97.9%) |

| 1 | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Clinical T stage | ||

| T2 | 25 (48.1%) | 24 (51.1%) |

| T3 | 24 (46.1%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| T4 | 3 (5.8%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Urinary diversion/reconstruction | ||

| Ureterocutaneostomy | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (6.4%) |

| Ileal conduit | 28 (53.9%) | 26 (55.3%) |

| Continent reservoir | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Orthotopic neobladder | 19 (36.5%) | 14 (29.8%) |

| Others | 1 (1.9%) | 3 (6.4%) |

| Characteristics . | RC arm (N = 52) . | NAC arm (N = 47) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 63 | 63 |

| ≤60 | 18 (34.6%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| ≥61 | 34 (65.3%) | 25 (53.2%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48 (92.3%) | 41 (87.2%) |

| Female | 4 (7.7%) | 6 (12.8%) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 51 (98.1%) | 46 (97.9%) |

| 1 | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Clinical T stage | ||

| T2 | 25 (48.1%) | 24 (51.1%) |

| T3 | 24 (46.1%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| T4 | 3 (5.8%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Urinary diversion/reconstruction | ||

| Ureterocutaneostomy | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (6.4%) |

| Ileal conduit | 28 (53.9%) | 26 (55.3%) |

| Continent reservoir | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Orthotopic neobladder | 19 (36.5%) | 14 (29.8%) |

| Others | 1 (1.9%) | 3 (6.4%) |

RC, radical cystectomy; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status.

| Characteristics . | RC arm (N = 52) . | NAC arm (N = 47) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 63 | 63 |

| ≤60 | 18 (34.6%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| ≥61 | 34 (65.3%) | 25 (53.2%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48 (92.3%) | 41 (87.2%) |

| Female | 4 (7.7%) | 6 (12.8%) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 51 (98.1%) | 46 (97.9%) |

| 1 | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Clinical T stage | ||

| T2 | 25 (48.1%) | 24 (51.1%) |

| T3 | 24 (46.1%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| T4 | 3 (5.8%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Urinary diversion/reconstruction | ||

| Ureterocutaneostomy | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (6.4%) |

| Ileal conduit | 28 (53.9%) | 26 (55.3%) |

| Continent reservoir | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Orthotopic neobladder | 19 (36.5%) | 14 (29.8%) |

| Others | 1 (1.9%) | 3 (6.4%) |

| Characteristics . | RC arm (N = 52) . | NAC arm (N = 47) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 63 | 63 |

| ≤60 | 18 (34.6%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| ≥61 | 34 (65.3%) | 25 (53.2%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48 (92.3%) | 41 (87.2%) |

| Female | 4 (7.7%) | 6 (12.8%) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 51 (98.1%) | 46 (97.9%) |

| 1 | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Clinical T stage | ||

| T2 | 25 (48.1%) | 24 (51.1%) |

| T3 | 24 (46.1%) | 22 (46.8%) |

| T4 | 3 (5.8%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Urinary diversion/reconstruction | ||

| Ureterocutaneostomy | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (6.4%) |

| Ileal conduit | 28 (53.9%) | 26 (55.3%) |

| Continent reservoir | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Orthotopic neobladder | 19 (36.5%) | 14 (29.8%) |

| Others | 1 (1.9%) | 3 (6.4%) |

RC, radical cystectomy; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status.

During MVAC, the most commonly reported grade 3–4 event was neutropenia. Non-haematological toxicities were less common. There was no treatment-related death during chemotherapy, and no cystectomy was delayed due to AEs. There were no differences in operative time, estimated blood loss, proportion of transfusions, number of lymph nodes removed or intraoperative complications between the arms. No significant differences in the incidence of early or late complications were observed between the arms.

The median baseline HRQoL scores were similar in the NAC and RC arms (median total FACT-BL 95.67 [interquartile range (IQR) 88.67–108] for NAC vs 97.67 [83.33–105.8] for RC).

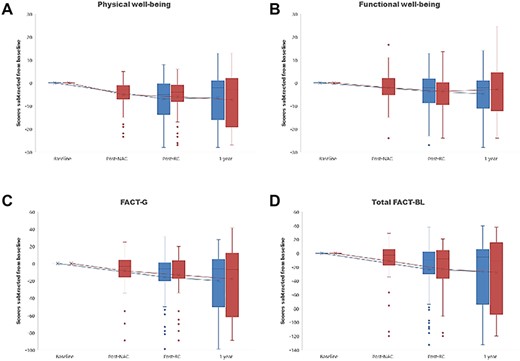

Patients in the NAC arm experienced HRQoL decline after MVAC in the domains of physical well-being (from 0 to median − 3 [IQR −7–−1], P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A), functional well-being (0 to −2.08 [−5–2], P = 0.033) (Fig. 2B), FACT-G total (0 to −3.42 [−15.33–4], P = 0.008) (Fig. 2C), C2 (weight loss; 0 to −1 [−2–0], P = 0.006) (Supplementary Fig. 1A), C5 (diarrhoea; 0 to 0 [0–0], P = 0.016) (Supplementary Fig. 1B), C6 (appetite; 0 to 0 [−1–0], P = 0.008) (Supplementary Fig. 1C), C7 (body appearance; 0 to 0 [−1–0], P = 0.004) (Supplementary Fig. 1D), C8 (embarrassment by ostomy appliance; 0 to −3 [−4–−2], P = 0.007) (Supplementary Fig. 1E), and total FACT-BL (0 to −2.77 [−16.2–5], P = 0.022) (Fig. 2D). There was no difference in scores for these domains between the two arms after RC and 1 year after registration, except that at the post-cystectomy assessment, the C8 scores in the NAC arm were significantly lower than in the RC arm (median − 3 [IQR −4–−2] vs median − 0.5 [IQR −1–0], P = 0.001) (Fig. 2H).

Change in the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bladder (FACT-BL) domain scores over time in patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by RC. A, physical well-being; B, functional well-being; C, FACT-G total; D, total FACT-BL; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC, radical cystectomy.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report prospectively assessing and comparing HRQoL outcomes between NAC followed by RC and RC alone in MIBC from baseline to 1 year after registration. HRQoL deteriorated after 2 cycles of NAC, although we previously reported that NAC-related toxicities, assessed by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) grading, were expected and well managed. Of the domains in which the scores declined during neoadjuvant MVAC in the NAC arm, physical and functional well-being were related not only to the patients’ physical condition, but also to contentment for daily life. This discrepancy between NCI-CTC grading and HRQoL score supports HRQoL and PRO measures as mandatory endpoints in clinical cancer trials (23).

It is noteworthy that there were no differences in HRQoL scores between the NAC and RC arms after RC and thereafter, except for the embarrassment by ostomy appliance at the time of post-cystectomy. There could be several reasons for the results. First, patients might overwhelmingly suffer from symptoms and/or conditions after RC rather than NAC. All cystectomies in this trial were performed by open procedure, but a previous prospective study showed no significant differences among HRQoL scores between open RC and the robot-assisted laparoscopic RC cohorts (24), implying that RC may impose a burden on patients’ HRQoL regardless of the type of cystectomy procedure. Second, physical, emotional and functional status might be affected by urinary diversion rather than NAC. Several studies (16, 25–27) have demonstrated the decline of HRQoL in patients who underwent RC with urinary diversion. HRQoL might thus be related not to the invasiveness of cystectomy itself but to urinary diversion. Finally, it is possible that patients who received NAC accepted and recovered from the HRQoL-decreased status in the period between the termination of NAC and RC. However, this reason seems unlikely, since the FACT-G and FACT-BL scores declined from the assessment after NAC to that after RC in the NAC arm.

Some randomized trials compared HRQoL in patients with cancers other than bladder cancer who received NAC or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT). In a recent trial comparing carboplatin plus paclitaxel-based NCRT plus surgery with surgery alone in oesophageal or oesophagogastric junctional cancer, no negative effect of NCRT was apparent on postoperative HRQoL, although HRQoL declined during NCRT (28). Meanwhile, another randomized trial showed that NAC was associated with superior optimal cytoreduction, lower peri-operative morbidity and better HRQoL compared to primary debulking surgery in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (29), as also demonstrated by a meta-analysis (30). In the present trial, the median tumour diameter was 3 cm (ranging from 0.5 to 8), indicating that the diameter itself did not cause tumour-related symptoms in MIBC patients. Thus, NAC may not provide an improvement in QoL, unlike for ovarian cancer patients, even if bladder lesions respond remarkably well to NAC.

The reason why the patients in the NAC arm had worse scores for C8 (‘I am embarrassed by my ostomy appliance’) than those in the RC arm at post-cystectomy assessment is unclear. However, the absence of significant differences in any HRQoL score between the arms in the assessment 1 year after registration suggests that all patients in both arms accepted and adapted to their status in the long term, compatibly with the results of a study reporting that it might take 12 months for HRQoL to return to baseline after RC (26).

Emerging novel therapies have stimulated the development of tools for PRO collection. To better understand the impact of disease and of such therapies on HRQoL, PRO data collection appears to be mandatory in recent clinical trials. Degboe et al. (19) evaluated the psychometric properties of the FACT-BL in patients with advanced UC, concluding that its use is consistent with the FDA guidelines for PRO validation. Thus, we consider the FACT-BL as one of the best tools for HRQoL assessment in bladder cancer patients.

The limitations of this study include the relatively lower response rate in the both arm. Furthermore, the number of patients who completed the questionnaires until 1 year after registration was also insufficient in both the NAC (30/64, 46.9%) and the RC (36/64, 56.3%) arms. This was due to the fact that we did not press patients who did not respond to complete and send the questionnaires.

Conclusion

Although HRQoL declined during NAC, no negative effect of NAC on HRQoL was apparent after RC and thereafter, supporting the view that neoadjuvant MVAC should be regarded as a standard of care for patients with MIBC, also from the point of view of HRQoL.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their family members. We are also grateful to the members of the JCOG Data Center and JCOG Operations Office for their support in preparing the manuscript (Dr. Hiroshi Katayama and Dr. Keita Sasaki), data management (Ms. Kazumi Kubota) and their oversight of the study management (Dr. Haruhiko Fukuda). We are also grateful to Dr. Ken-ichi Tobisu and Dr. Yoshiyuki Kakehi, the previous group chairs of the JCOG Urologic Oncology Study Group.

Funding

This work was supported by Health Sciences Research Grants for Medical Frontier Strategy Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for Clinical Research for Evidenced-Based Medicine from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for Clinical Cancer Research [H16-26 and H22-26] from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research [17S-4, 17S-5, 20S-4 and 20S-6] from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; and National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund [23-A-16, 23-A-20 and 29-A-3].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

Appendix

The following 28 institutions (listed from north to south) participated: Hokkaido University Hospital; Sapporo Medical University; Tohoku University Hospital; Akita University School of Medicine; Yamagata University Hospital; Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba; Tochigi Cancer Center; Chiba University, Graduate School of Medicine; National Cancer Center Hospital; Teikyo University School of Medicine; Kitasato University School of Medicine; Niigata Cancer Center Hospital; University of Yamanashi Faculty of Medicine; Hamamatsu University School of Medicine; Shizuoka Cancer Center; Nagoya University School of Medicine; Mie University School of Medicine; Kyoto University Hospital; Osaka International Cancer Institute; Nara Medical University; Faculty of Medicine, Kagawa University; National Hospital Organization Shikoku Cancer Center; National Kyushu Cancer Center; Kurume University School of Medicine; Kyushu University Hospital; Hara Sanshin Hospital; Kumamoto University Medical School; Kagoshima University, Faculty of Medicine.