-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rito L Mikhari, Susan Meiring, Linda de Gouveia, Wai Yin Chan, Keith A Jolley, Daria Van Tyne, Lee H Harrison, Henju Marjuki, Arshad Ismail, Vanessa Quan, Cheryl Cohen, Sibongile Walaza, Anne von Gottberg, Mignon du Plessis, Genomic Diversity and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Invasive Neisseria meningitidis in South Africa, 2016–2021, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 230, Issue 6, 15 December 2024, Pages e1311–e1321, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiae225

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Invasive meningococcal isolates in South Africa have in previous years (<2008) been characterized by serogroup B, C, W, and Y lineages over time, with penicillin intermediate resistance (peni) at 6%. We describe the population structure and genomic markers of peni among invasive meningococcal isolates in South Africa, 2016–2021.

Meningococcal isolates were collected through national, laboratory-based invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) surveillance. Phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing and whole-genome sequencing were performed, and the mechanism of reduced penicillin susceptibility was assessed in silico.

Of 585 IMD cases reported during the study period, culture and PCR-based capsular group was determined for 477/585 (82%); and 241/477 (51%) were sequenced. Predominant serogroups included NmB (210/477; 44%), NmW (116/477; 24%), NmY (96/477; 20%), and NmC (48/477; 10%). Predominant clonal complexes (CC) were CC41/44 in NmB (27/113; 24%), CC11 in NmW (46/56; 82%), CC167 in NmY (23/44; 53%), and CC865 in NmC (9/24; 38%). Peni was detected in 16% (42/262) of isolates, and was due to the presence of a penA mosaic, with the majority harboring penA7, penA9, or penA14.

IMD lineages circulating in South Africa were consistent with those circulating prior to 2008; however, peni was higher than previously reported, and occurred in a variety of lineages.

Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) causes invasive meningococcal disease (IMD), with a global case fatality ranging from 4% to 20% despite antibiotic therapy [1]. IMD incidence varies globally, with the majority of high-income countries currently at <1 per 100 000 persons [2]; however, incidence in many low-income countries cannot be correctly evaluated due to suboptimal surveillance. Because of the propensity to cause regional outbreaks and epidemics, along with the rise in decreased susceptibility to penicillin globally [3], it is crucial to monitor molecular diversity and antimicrobial susceptibility of meningococcal isolates circulating in current years through national surveillance systems.

IMD is a category 1 notifiable medical condition in South Africa, and national, laboratory-based surveillance has been active since 1999 [4]. South Africa is a temperate country outside of the meningitis belt, and 4 serogroups commonly cause IMD, namely, NmB, NmC, NmW, and NmY [5]. Notably, IMD incidence has decreased from 1.4 per 100 000 persons in 2006 to 0.19 per 100 000 persons in 2019 in the absence of routine meningococcal vaccination and availability of vaccines in the public sector [5, 6]. Vaccination is recommended only for high-risk population groups such as those with immunodeficiencies [7]. The majority of NmB isolates in 2006 and preceding years were caused by clonal complexes (CCs) CC41/44/lineage 3, CC32/ET-5, and CC4240/6688 [8]. NmW strains were dominated by the hypervirulent CC11/ET-37 [9], NmY was mostly CC/ST-23 [10], and NmC was characterized by CC32, CC11/ET-37, and CC865 [11].

In South Africa, third-generation cephalosporins are recommended for empiric treatment of bacterial meningitis, transitioning to penicillin following laboratory confirmation of N. meningitidis [12]. Ciprofloxacin, with rifampicin as an alternative, is recommended for prophylactic treatment to eradicate carriage in close contacts [12]. In an earlier study (2001–2005) using IMD surveillance data, 6% of N. meningitidis isolates were intermediately resistant to penicillin (peni) [13]. Globally, varying rates of penicillin nonsusceptibility have been reported, ranging from 25% to 72% between 2010 and 2021 in Europe, the United States, Australia, and Japan [14–17]. Penicillin nonsusceptibility is mainly due to mutations in the penA gene, which encodes penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2) [18]. Resistance due to β-lactamase production has also been reported [19]. Fluoroquinolone and rifampicin resistance have been reported in other countries [3]; however, resistance is rare in South Africa [20]. For fluoroquinolones, quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR) occur within the gyrA and parC genes [21]. Rifampicin resistance is derived from mutations in the rpoB gene, which encodes the DNA topoisomerase subunit of RNA polymerase, including mutations H552N and D542E [14].

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, preventative measures hindered the human interaction required for disease transmission, causing a significant drop in IMD incidence, with a postpandemic resurgence [22]. Integration of systematic genomic characterization of N. meningitidis into the national surveillance system is useful to better understand disease epidemiology and support decision making towards treatment, prevention, and control. Importantly, surveillance is one of the pillars in the World Health Organization's framework for the global roadmap to defeating meningitis by 2030 [23]. We describe the molecular epidemiology and mechanism of penicillin nonsusceptibility among invasive isolates in South Africa.

METHODS

Invasive Meningococcal Disease Surveillance, 2016–2021

N. meningitidis isolates, and/or clinical specimens, and demographic data from hospitalized patients were collected as part of national, laboratory-based surveillance from all provinces of South Africa, and submitted to the national reference laboratory for further characterization. A case of IMD was defined as the detection of N. meningitidis in a normally sterile body fluid based on laboratory test results using bacterial culture, antigen detection, and/or real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [4]. IMD incidence (per 100 000 persons) was calculated based on the number of laboratory-confirmed cases reported annually from 1 January 2016 through 31 December 2021, divided by the mid-year population estimates for each year as supplied by Statistics South Africa [24].

At the reference laboratory, serogroup was determined using polyclonal antiserum followed by capsule-specific monoclonal antiserum (Remel Biotech, Ltd) against serogroups A, B, C, X, Y, Z, and W. PCR assigned genogroup by detection of csaB, csb, csc, csw, csxB, and csy genes, corresponding to serogroups A, B, C, W, X, and Y, respectively [25], for bacterial isolates and clinical specimens.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was performed on viable isolates using the disc diffusion method for ceftriaxone, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, penicillin, and rifampicin. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) using E-test (AB Biodisk) was performed if disc diffusion indicated nonsusceptibility, with the exception of penicillin where E-test was performed on all isolates. Results were interpreted using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [26]. β-lactamase production was tested on all isolates using Nitrocefin (Oxoid, Ltd).

Whole-Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from N. meningitidis cultures using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen) and Qubit dsDNA BR assay kits were used for quantification of the extracted genomic DNA to a concentration of >10 ng/µL. Multiplexed, paired-end libraries (2 × 150 bp) were prepared using the Illumina DNA Prep kit (Illumina), followed by sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000 platforms (Illumina) with 100× coverage. Resulting raw sequence reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic software (version 0.38) [27] prior to de novo assembly using SPAdes (version 3.12.0) [28].

Genomic Characterization

Assembled genomes were submitted to the Neisseria PubMLST public database (http://pubMLST.org/neisseria/) [29], which hosts data using the Bacterial Isolate Genome Sequence platform for sequence curation and annotation. Genomic characterization was conducted for genogroup, sequence type (ST), CC, and fine-typing alleles (PorA VR1 and VR2, and ferric enterochelin receptor [FetA]). Phenotypic serogroup and genogroup deduced from PCR and genomic data were discordant for 3 isolates, which were no longer viable for repeat testing and were excluded from further analysis. Antimicrobial resistance-conferring genes (penA, blaROB-1, gyrA, and parC) were assessed using the Bacterial Meningitis Genomic Analysis Platform (BMGAP) [30].

PenA Gene Analysis

PenA genes were screened for mutations F504L, A510V, I515V, H541N, and I566V (known to confer penicillin non-susceptibility) [18]. PenA gene fragments were mapped against a reference penA gene (NmB MC58, accession No. AY127670) using Snippy-core (version 4.3) (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) [31]. Results were correlated with MIC.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogeny was determined for all isolate genomes (n = 241) using core-genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) based on gene-to-gene differentiation, relative to NmB strain MC58 [32]. A multiple sequence alignment was constructed using Snippy-core, and a maximum likelihood tree was constructed using RAxML (version 8.2.12) [33], and visualized and annotated using iTOL [34].

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the national surveillance program (GERMS-SA) and this study, was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Health Research Ethics Committee (M1809107 and M210689, respectively).

RESULTS

Invasive Meningococcal Disease Surveillance, 2016–2021

During the study period, 585 IMD episodes were reported through GERMS-SA, of which 34% (201/585) occurred in children aged <5 years and 53% (309/585) were male. Cases were geographically widespread over the 9 provinces: Western Cape (222/585; 38%), Gauteng (168/585; 29%), Eastern Cape (83/585; 14%), KwaZulu-Natal (48/585; 8%), North West (22/585; 4%), Mpumalanga (13/585; 2%), Free State (14/585; 2%), Limpopo (11/585; 2%), and Northern Cape (4/585; 1%). The reference laboratory received 502 samples for N. meningitidis confirmation and characterization, of which 276 of 502 (55%) were bacterial cultures and 226 of 502 (45%) were clinical specimens with no isolate available. Eighty-three cases (83/585, 14%) were identified during routine laboratory surveillance audits with no culture or specimen available for further characterization (Supplementary Figure 1). Serogroup was determined for 262 of 276 (95%) cultures and 215 of 226 (95%) clinical specimens. A serogroup was not assigned in 25 samples; 11 were culture-negative clinical specimens (N. meningitidis detected by PCR), and PCR-based genogroup could not be performed due to depleted specimen volume or low bacterial load (cycle threshold >35). The remaining 14 samples were cultures that lost viability and no further testing was performed. Serogroup distribution was as follows: NmB (210/477; 44%), NmW (116/477; 24%), NmY (96/477; 20%), and NmC (48/477; 10%). Five isolates were nongroupable, and there was 1 each of NmE and NmZ. NmZ was isolated from a person with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Genomic data were available for 241 of 262 (94%) isolates (Supplementary Figure 1), representing 41% (241/585) of reported IMD cases.

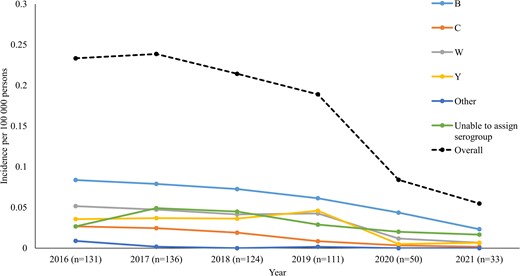

Annual IMD incidence per 100 000 persons was 0.23, 0.24, 0.21, 0.19, 0.08, and 0.04 for the years 2016 to 2021, and the mean overall incidence for this period was 0.19 (Figure 1). NmB was most common, with an average incidence per 100 000 persons of 0.07, followed by NmW, NmY, and NmC at 0.038, 0.036, and 0.016, respectively (Figure 1). The highest age-specific incidence was in infants <1 year of age (Supplementary Figure 2). The highest IMD incidence was in Western Cape Province (average incidence 0.62), followed by Gauteng Province (average incidence 0.22) (Supplementary Figures 3 and 4).

Incidence of invasive meningococcal disease by serogroup and year, South Africa, 2016–2021 (N = 585). “Other” includes Z (n = 1), nongroupable (n = 5), and E (n = 1). Isolates in the “unable to assign serogroup” category were 108 of 585 (18%).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined for 262 isolates, of which 16% (42/262) were peni (MIC50 = 0.047 mg/L and MIC90 = 0.125 mg/L) (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). None of the isolates tested positive for ß-lactamase production. The proportion of peni isolates during the study period ranged from 3% (8/70) in 2017 to 35% (8/23) in 2020. Half of peni isolates were NmB (22/42; 51%), followed by NmW (10/42; 24%), NmY (9/42; 21%), and NmC (1/42; 2%). Intermediate resistance to ciprofloxacin was observed in a single isolate; this isolate could not be sequenced due to loss of viability. All isolates were susceptible to ceftriaxone and chloramphenicol (262/262; 100%). Resistance to rifampicin was observed in 3 of 262 (1%) isolates.

Of 241 available genomes, 38 of 241 (16%) were phenotypically peni; however, 9 of 38 (24%) isolates did not harbor any of the abovementioned 5 mutations in PBP2. They either had no mutations (n = 2) or harbored only V247A (n = 4) or D183N, V247A, and 345R_insD_346D insertion (n = 3), none of which have been verified to contribute to penicillin nonsusceptibility in N. meningitidis. Among the phenotypically penicillin susceptible (pens) isolates (203/241, 84%), 12 of 203 (6%) isolates harbored the 5 commonly described PBP2 mutations associated with penicillin nonsusceptibility. For the 21 isolates where phenotypic AST and in silico predicted results for penicillin susceptibility or nonsuscpetibility did not correlate, 13 of 21 (62%) had an MIC value 1 dilution below or above the CLSI cutoff value for penicillin nonsusceptibility. These findings were verified by repeat MIC testing and genome sequencing.

PenA Gene Characterization

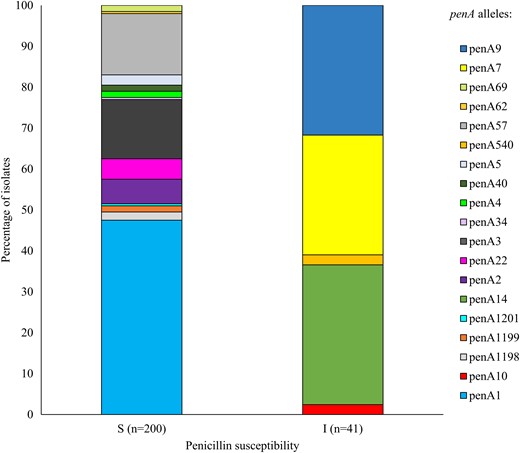

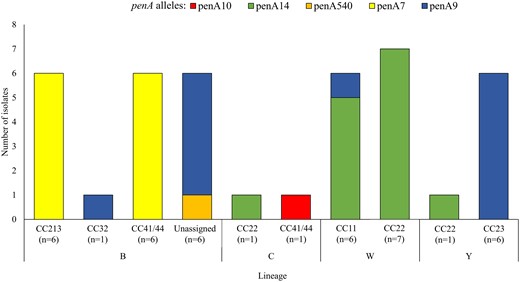

None of the isolates tested positive for ß-lactamase production. Seventeen percent (41/241) of isolates were characterized as peni and all harbored the 5 common PBP2 mutations. A total of 200 of 241 (83%) isolates were predicted to be pens based on the absence of these mutations: 95 of 200 (48%) pens isolates harbored penA1, followed by penA57 and penA3 detected in 15% (30/200) and 15% (29/200) of isolates, respectively (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The peni isolates harbored 1 of 5 penA alleles and belonged to 4 serogroups and 6 different lineages. The majority of isolates harbored either the penA9 allele (13/41; 32%), present in NmB:CC32 (1/13; 8%), NmB:unassigned (5/13; 38%), NmW:CC11 (1/13; 8%), and NmY:CC23 (6/13; 46%) isolates; the penA14 allele (14/41; 34%), found in NmW:CC22 (7/14; 50%), NmW:CC11 (5/14; 36%), NmC:CC22 (1/14; 7%), and NmY:CC22 (1/14; 7%); or the penA7 allele (12/41; 29%), found only in NmB lineages CC213 (6/12; 50%) and CC41/44 (6/12; 50%) (Figure 4). Most of the peni strains possessing penA14 (10/14; 71%), penA9 (12/13; 92%), and penA7 (12/12; 100%) were isolated from patients of varying ages, either from Gauteng or Western Cape where IMD incidence was highest. Furthermore, all 3 penA alleles were in isolates spanning at least 4 of the study years. Additional PBP2 mutations known to cause decreased susceptibility to penicillin and cephalosporins in pathogenic Neisseria species were detected in some isolates, including I312M (2/41; 5%), V316T (2/41; 5%), N512Y (12/41; 29%), A549V (13/41; 32%), A574V (24/41; 59%), and an N insertion between positions 573 and 574 (25/41; 61%).

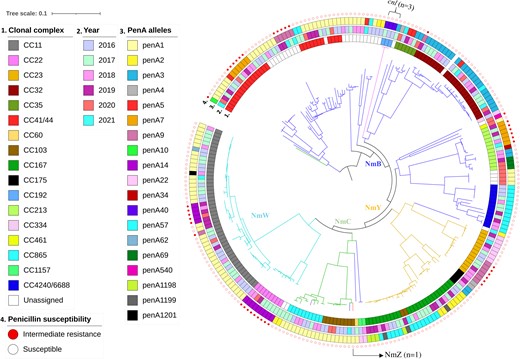

Core-genome maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree representative of the population structure of invasive meningococcal isolates, South Africa, 2016–2021 (N = 241). Serogroups are represented by branch color, including NmB (n = 113), NmW (n = 56), NmY (n = 44), NmC (n = 24), NmZ (n = 1), and cnl (n = 3). Color strips from the inner to outer rings illustrate (1) clonal complex, (2) epidemiological year, (3) penA alleles, and (4) penicillin susceptibility. Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; cnl, capsule null locus genotype.

Distribution of penA alleles among invasive meningococcal isolates corresponding to penicillin susceptibility based on genomic data, South Africa, 2016–2021 (N = 241). Abbreviations: I, penicillin intermediate resistance; S, penicillin susceptible.

PenA gene alleles detected among invasive meningococcal isolates intermediately resistant to penicillin, by serogroup and lineage, South Africa, 2016 to 2021 (n = 41).

rpoB Gene Characterization

Among the 3 rifampicin-resistant isolates confirmed by AST, rpoB alleles from 2 isolates were identified as new alleles, namely, rpoB286 of lineage W: P1.5,2: F1-1: ST-11 (CC11) and rpoB287 of lineage B: P1.7,9: F3-20: ST-6590 (CC41/44). For the third isolate there was a discrepancy between the AST results (nonsusceptible) and the assigned rpoB allele (rpoB9 which does not harbor any critical mutations). Repeat testing could not be performed due to loss of isolate viability.

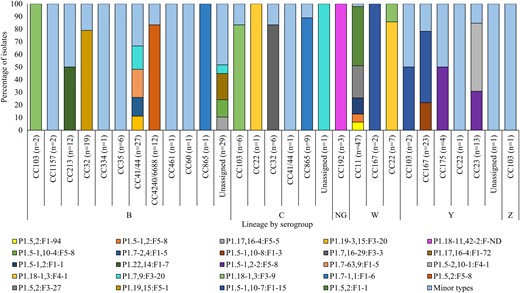

Genogroup Assignment and Lineage Distribution

The in silico assignment of genogroups among 241 invasive meningococcal isolates was NmB (113/241, 47%), NmW (56/241, 23%), NmY (43/241, 18%), NmC (24/241, 10%), and NmZ (1/241, 0.4%) (Figure 2, Figure 5, and Table 1). Three isolates (3/241; 1%) were nongroupable and all harbored the capsule null locus (cnl) (Table 1). Lineages were distributed throughout the study period (Figure 2).

Diversity of PorA:FetA variants contributing >1% of invasive meningococcal diseases isolates (N = 241), South Africa, 2016–2021. Data were extracted from the PubMLST Neisseria database using the export dataset analysis tool. The rest of the variants were categorized as minor types (Supplementary Table 2). Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; NG, nongroupable.

Sequence Types and Clonal Complexes Among Invasive Meningococcal Isolates, South Africa, 2016–2021 (n = 241)

| Serogroup, No. (%) . | CC . | No. of Isolates (%) . | ST (No. of Isolates) . | No. of ST . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B, 113 (47) | CC41/44 | 27 (24) | 13 850 (6), 6590 (6), 154 (4), 15 920 (2)a, 44 (1), 191 (1), 485 (1), 944 (1), 4244 (1), 6617 (1), 13 851 (1), 14 290 (1), 15 921 (1)a | 13 |

| CC32 | 19 (17) | 33 (14), 32 (2), 7460 (1), 10 245 (1), 15 933 (1)a | 5 | |

| CC4240/6688 | 12 (11) | 8102 (5), 16 092 (2), 4240 (1), 8602 (1), 13 849 (1), 13 854 (1), 15 926 (1)a | 7 | |

| CC213 | 12 (11) | 213 (11), 4531 | 2 | |

| CC35 | 6 (5) | 35 (3), 472 (1), 14 291 (1), 15 919 (1)a | 4 | |

| CC103 | 2 (2) | 1878 (1), 103 (1) | 2 | |

| CC1157 | 2 (2) | 1157 (2) | 1 | |

| CC334 | 1 (1) | 334 (1) | 1 | |

| CC865 | 1 (1) | 7180 (1) | 1 | |

| CC60 | 1 (1) | 905 (1) | 1 | |

| CC46 | 1 (1) | 15 934 (1)a | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 29 (26) | 8597 (5), 15 929 (4)a, 7167 (4), 6709 (3), 3982 (1), 5436 (1), 11 539 (1), 13 855 (1), 13 995 (1), 13 996 (1), 14 292 (1), 16 028 (1)a, 16 029 (1)a, 11 539 (1), 3105 (1), 16 216 (1), 17 947 (1), unknown (1) | 17 | |

| W, 56 (23) | CC11 | 46 (82) | 11 (45), 10 651 (1) | 2 |

| CC22 | 7 (13) | 184 (7) | 1 | |

| CC167 | 2 (4) | 884 (2) | 1 | |

| CC32 | 1 (2) | 33 (1) | 1 | |

| Y, 44 (18) | CC167 | 23 (53) | 884 (12), 767 (7), 13 848 (3), 167 (1) | 4 |

| CC23 | 13 (30) | 4245 (7), 6800 (5), 13 846 (1) | 3 | |

| CC175 | 4 (10) | 175 (2), 6218 (2) | 2 | |

| CC103 | 2 (5) | 15 923 (2)a | 1 | |

| CC22 | 1 (2) | 184 (1) | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (2) | 5436 (1) | 1 | |

| C, 24 (10) | CC865 | 9 (38) | 8608 (3), 16 030 (2), 865 (2), 7180 (1), 13 847 (1) | 5 |

| CC103 | 6 (25) | 103 (5), 15 922 (1)a | 2 | |

| CC32 | 6 (25) | 32 (6) | 6 | |

| CC41/44 | 1 (4) | 206 | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (4) | 13 853 | 1 | |

| Cnl, 3 (1) | CC192 | 3 (100) | 192 (3) | 1 |

| Z, 1 (0.4) | CC103 | 1 (100) | 103 (1) | 1 |

| Total | 241 |

| Serogroup, No. (%) . | CC . | No. of Isolates (%) . | ST (No. of Isolates) . | No. of ST . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B, 113 (47) | CC41/44 | 27 (24) | 13 850 (6), 6590 (6), 154 (4), 15 920 (2)a, 44 (1), 191 (1), 485 (1), 944 (1), 4244 (1), 6617 (1), 13 851 (1), 14 290 (1), 15 921 (1)a | 13 |

| CC32 | 19 (17) | 33 (14), 32 (2), 7460 (1), 10 245 (1), 15 933 (1)a | 5 | |

| CC4240/6688 | 12 (11) | 8102 (5), 16 092 (2), 4240 (1), 8602 (1), 13 849 (1), 13 854 (1), 15 926 (1)a | 7 | |

| CC213 | 12 (11) | 213 (11), 4531 | 2 | |

| CC35 | 6 (5) | 35 (3), 472 (1), 14 291 (1), 15 919 (1)a | 4 | |

| CC103 | 2 (2) | 1878 (1), 103 (1) | 2 | |

| CC1157 | 2 (2) | 1157 (2) | 1 | |

| CC334 | 1 (1) | 334 (1) | 1 | |

| CC865 | 1 (1) | 7180 (1) | 1 | |

| CC60 | 1 (1) | 905 (1) | 1 | |

| CC46 | 1 (1) | 15 934 (1)a | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 29 (26) | 8597 (5), 15 929 (4)a, 7167 (4), 6709 (3), 3982 (1), 5436 (1), 11 539 (1), 13 855 (1), 13 995 (1), 13 996 (1), 14 292 (1), 16 028 (1)a, 16 029 (1)a, 11 539 (1), 3105 (1), 16 216 (1), 17 947 (1), unknown (1) | 17 | |

| W, 56 (23) | CC11 | 46 (82) | 11 (45), 10 651 (1) | 2 |

| CC22 | 7 (13) | 184 (7) | 1 | |

| CC167 | 2 (4) | 884 (2) | 1 | |

| CC32 | 1 (2) | 33 (1) | 1 | |

| Y, 44 (18) | CC167 | 23 (53) | 884 (12), 767 (7), 13 848 (3), 167 (1) | 4 |

| CC23 | 13 (30) | 4245 (7), 6800 (5), 13 846 (1) | 3 | |

| CC175 | 4 (10) | 175 (2), 6218 (2) | 2 | |

| CC103 | 2 (5) | 15 923 (2)a | 1 | |

| CC22 | 1 (2) | 184 (1) | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (2) | 5436 (1) | 1 | |

| C, 24 (10) | CC865 | 9 (38) | 8608 (3), 16 030 (2), 865 (2), 7180 (1), 13 847 (1) | 5 |

| CC103 | 6 (25) | 103 (5), 15 922 (1)a | 2 | |

| CC32 | 6 (25) | 32 (6) | 6 | |

| CC41/44 | 1 (4) | 206 | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (4) | 13 853 | 1 | |

| Cnl, 3 (1) | CC192 | 3 (100) | 192 (3) | 1 |

| Z, 1 (0.4) | CC103 | 1 (100) | 103 (1) | 1 |

| Total | 241 |

Prevalent sequence types are indicated in bold.

Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; ST, sequence type.

aNewly assigned sequence type.

Sequence Types and Clonal Complexes Among Invasive Meningococcal Isolates, South Africa, 2016–2021 (n = 241)

| Serogroup, No. (%) . | CC . | No. of Isolates (%) . | ST (No. of Isolates) . | No. of ST . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B, 113 (47) | CC41/44 | 27 (24) | 13 850 (6), 6590 (6), 154 (4), 15 920 (2)a, 44 (1), 191 (1), 485 (1), 944 (1), 4244 (1), 6617 (1), 13 851 (1), 14 290 (1), 15 921 (1)a | 13 |

| CC32 | 19 (17) | 33 (14), 32 (2), 7460 (1), 10 245 (1), 15 933 (1)a | 5 | |

| CC4240/6688 | 12 (11) | 8102 (5), 16 092 (2), 4240 (1), 8602 (1), 13 849 (1), 13 854 (1), 15 926 (1)a | 7 | |

| CC213 | 12 (11) | 213 (11), 4531 | 2 | |

| CC35 | 6 (5) | 35 (3), 472 (1), 14 291 (1), 15 919 (1)a | 4 | |

| CC103 | 2 (2) | 1878 (1), 103 (1) | 2 | |

| CC1157 | 2 (2) | 1157 (2) | 1 | |

| CC334 | 1 (1) | 334 (1) | 1 | |

| CC865 | 1 (1) | 7180 (1) | 1 | |

| CC60 | 1 (1) | 905 (1) | 1 | |

| CC46 | 1 (1) | 15 934 (1)a | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 29 (26) | 8597 (5), 15 929 (4)a, 7167 (4), 6709 (3), 3982 (1), 5436 (1), 11 539 (1), 13 855 (1), 13 995 (1), 13 996 (1), 14 292 (1), 16 028 (1)a, 16 029 (1)a, 11 539 (1), 3105 (1), 16 216 (1), 17 947 (1), unknown (1) | 17 | |

| W, 56 (23) | CC11 | 46 (82) | 11 (45), 10 651 (1) | 2 |

| CC22 | 7 (13) | 184 (7) | 1 | |

| CC167 | 2 (4) | 884 (2) | 1 | |

| CC32 | 1 (2) | 33 (1) | 1 | |

| Y, 44 (18) | CC167 | 23 (53) | 884 (12), 767 (7), 13 848 (3), 167 (1) | 4 |

| CC23 | 13 (30) | 4245 (7), 6800 (5), 13 846 (1) | 3 | |

| CC175 | 4 (10) | 175 (2), 6218 (2) | 2 | |

| CC103 | 2 (5) | 15 923 (2)a | 1 | |

| CC22 | 1 (2) | 184 (1) | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (2) | 5436 (1) | 1 | |

| C, 24 (10) | CC865 | 9 (38) | 8608 (3), 16 030 (2), 865 (2), 7180 (1), 13 847 (1) | 5 |

| CC103 | 6 (25) | 103 (5), 15 922 (1)a | 2 | |

| CC32 | 6 (25) | 32 (6) | 6 | |

| CC41/44 | 1 (4) | 206 | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (4) | 13 853 | 1 | |

| Cnl, 3 (1) | CC192 | 3 (100) | 192 (3) | 1 |

| Z, 1 (0.4) | CC103 | 1 (100) | 103 (1) | 1 |

| Total | 241 |

| Serogroup, No. (%) . | CC . | No. of Isolates (%) . | ST (No. of Isolates) . | No. of ST . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B, 113 (47) | CC41/44 | 27 (24) | 13 850 (6), 6590 (6), 154 (4), 15 920 (2)a, 44 (1), 191 (1), 485 (1), 944 (1), 4244 (1), 6617 (1), 13 851 (1), 14 290 (1), 15 921 (1)a | 13 |

| CC32 | 19 (17) | 33 (14), 32 (2), 7460 (1), 10 245 (1), 15 933 (1)a | 5 | |

| CC4240/6688 | 12 (11) | 8102 (5), 16 092 (2), 4240 (1), 8602 (1), 13 849 (1), 13 854 (1), 15 926 (1)a | 7 | |

| CC213 | 12 (11) | 213 (11), 4531 | 2 | |

| CC35 | 6 (5) | 35 (3), 472 (1), 14 291 (1), 15 919 (1)a | 4 | |

| CC103 | 2 (2) | 1878 (1), 103 (1) | 2 | |

| CC1157 | 2 (2) | 1157 (2) | 1 | |

| CC334 | 1 (1) | 334 (1) | 1 | |

| CC865 | 1 (1) | 7180 (1) | 1 | |

| CC60 | 1 (1) | 905 (1) | 1 | |

| CC46 | 1 (1) | 15 934 (1)a | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 29 (26) | 8597 (5), 15 929 (4)a, 7167 (4), 6709 (3), 3982 (1), 5436 (1), 11 539 (1), 13 855 (1), 13 995 (1), 13 996 (1), 14 292 (1), 16 028 (1)a, 16 029 (1)a, 11 539 (1), 3105 (1), 16 216 (1), 17 947 (1), unknown (1) | 17 | |

| W, 56 (23) | CC11 | 46 (82) | 11 (45), 10 651 (1) | 2 |

| CC22 | 7 (13) | 184 (7) | 1 | |

| CC167 | 2 (4) | 884 (2) | 1 | |

| CC32 | 1 (2) | 33 (1) | 1 | |

| Y, 44 (18) | CC167 | 23 (53) | 884 (12), 767 (7), 13 848 (3), 167 (1) | 4 |

| CC23 | 13 (30) | 4245 (7), 6800 (5), 13 846 (1) | 3 | |

| CC175 | 4 (10) | 175 (2), 6218 (2) | 2 | |

| CC103 | 2 (5) | 15 923 (2)a | 1 | |

| CC22 | 1 (2) | 184 (1) | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (2) | 5436 (1) | 1 | |

| C, 24 (10) | CC865 | 9 (38) | 8608 (3), 16 030 (2), 865 (2), 7180 (1), 13 847 (1) | 5 |

| CC103 | 6 (25) | 103 (5), 15 922 (1)a | 2 | |

| CC32 | 6 (25) | 32 (6) | 6 | |

| CC41/44 | 1 (4) | 206 | 1 | |

| Unassigned CC | 1 (4) | 13 853 | 1 | |

| Cnl, 3 (1) | CC192 | 3 (100) | 192 (3) | 1 |

| Z, 1 (0.4) | CC103 | 1 (100) | 103 (1) | 1 |

| Total | 241 |

Prevalent sequence types are indicated in bold.

Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; ST, sequence type.

aNewly assigned sequence type.

NmB (n = 113)

Eleven CCs were identified among 83 of 113 (75%) isolates whilst the remainder of the isolates (29/113, 25%) belonged to 15 unrelated STs. Notably, 31% (9/29) of STs not assigned to a CC clustered with CC41/44 isolates. Dominant CCs included CC41/44 (27/113, 24%), CC32 (19/113, 17%), CC4240/6688 (12/113, 11%), and CC213 (12/113, 11%). Twenty-seven percent (30/113) of NmB PorA:FetA variant types were singletons. Subtype P1.19,15:F5-1 was present in 14 of 19 (74%) NmB isolates and was exclusively in CC32. Subtype P1.5,2:F5-8 was detected in 10 of 12 (83%) NmB isolates, all of which were CC4240/6688.

NmW (n = 56)

Four CCs were detected, namely, CC11 (46/56, 82%), CC22 (7/56, 13%), CC167 (2/56, 4%), and CC32 (1/56; 2%). Almost all CC11 isolates were ST11 (45/46, 98%). Prevalent subtypes in NmW:CC11 isolates were P1.5,2:F1-1 and P1.5,2:F3-27 (22/46; 48% and 12/46; 26% isolates, respectively).

NmY (n = 44)

CC167 and CC23 were most common (23/44; 52% and 12/44; 27%, respectively). CC175 was found in 10% (4/44) of isolates. The majority of CC167 isolates were ST884 (12/23; 52%), while CC23 isolates were mostly ST4245 (7/12, 58%). Subtype P1.5-1,10-7:F1-15 was found in 57% (13/23) of CC167, P1.5-2,10-1:F4-1 constituted in 58% (7/12) of CC23, while CC175 subtypes were P1.5-1,2-2:F1-47 and P1.5-1,2-2:F5-8 (2/4; 50% for each). P1.5-1,2-2:F5-8 was also detected in 33% (4/12) of CC23.

NmC (n = 24)

Among NmC isolates, 4 distinct CCs were assigned. CC865 contributed 38% (9/24), and 25% (6/24) of isolates were equally assigned to CC103 or CC32. ST8608 contributed a third of CC865 isolates (3/9; 33%). Most of the NmC isolates encoded P1.7-1,1:F1-6 (8/9; 89%) and were CC865.

Other serogroups (n = 4)

The NmZ meningococcal isolate belonged to CC103:ST103. The 3 nongroupable isolates were CC192:ST192, and outer membrane protein (OMP) encoded P1.18-11,42-2:F-ND. All 3 nongroupable genotypes clustered with NmB (unassigned CC) isolates.

DISCUSSION

A decrease in IMD incidence was observed during the study period, which reflects an ongoing trend from preceding years [6]. The notable decline in 2020 and 2021 was likely exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, in agreement with other studies [22]. Disease was caused by ongoing circulation of previously circulating lineages including the predominant NmB (CC41/44, CC32, CC4240/6688, and CC213), followed by NmC (CC865), NmW (CC11), and NmY (CC167 and CC23) [8, 9, 11, 35]. Penicillin nonsusceptibility was attributed to the presence of a penA mosaic and was associated with various serogroups and lineages.

Previous IMD surveillance data (2003–2016) showed existence of NmA (5%), NmB (23%), NmC (9%), NmW (50%), and NmY (12%) in South Africa [6]. In our study, similar serogroups and lineages continued to circulate, with the exception of NmA, which was last detected in 2010. Serogroups E and Z rarely cause IMD but have been reported in immunocompromised or complement-deficient individuals [36]. NmZ was from an individual with HIV, and no additional data were available for the NmE case.

Following extensive use of a NmA conjugate vaccine in the African meningitis belt smaller outbreaks have occurred, caused by NmC, NmW, and NmX [37–40], with no reported NmB disease. In Mozambique, serogroup distribution was different to that of South Africa, with NmA identified in 50% of bacterial meningitis surveillance samples in 2014 and 1% was NmB [41]. Our NmB lineages (CC41/44, CC32, and CC213) are similar to those circulating in Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, and South Korea [2]. NmB CC4240/6688 was detected in South Africa in the early 2000s, and was observed mostly in children <5 years old. It appears to have expanded among diseases-causing isolates in South Africa following the first detection of ST4240 and ST6688 and assignment of the clone (CC4240/6688), and to date has not been reported elsewhere [8].

The dominant NmC (CC32 and CC103) and Nm Y (CC167 and CC23) lineages in South Africa are known drivers of IMD in these serogroups in North America and Europe [42, 43]. Hypervirulent CC11 is usually associated with NmC and NmW, and less frequently, NmB. CC11 NmW has caused epidemics across the globe, having emerged from an outbreak in Saudi Arabia in 2000 [44]. It is characteristic of almost all NmW in South Africa, none belonging to NmC, unlike in the United States where CC11 is common among NmC strains [42] and in Canada where CC11 expresses both serogroup C and W capsules [45].

Predominant PorA:FetA OMP variants among NmB, and NmW are consistent with those detected in South Africa prior to 2006 [35], and NmW is known to possess a stable OMP profile [44]. The FetA component of historic NmY lineages was predominantly F5-8 (approximately 70%), which has been replaced by variant F1-15 in recent years. CC175, which accounted for 82% of isolates in 2003–2007, was observed in only 10% in this study. Although the dominant subtype for this lineage is unchanged, it appears to have been replaced by CC167 (from 6% in 2003–2007 to 52% currently), of which the PorA component has changed from P1.5-1,10-1 to P1.5-1,10-7 [46]. Nonetheless, an apparent increase in the overall OMP variant diversity was observed in the current study. In the United States, antigenic shift in PorA and FetA OMPs was found to increase incidence of NmY and NmC disease [47]. Despite the dominance of NmB disease in South Africa, NmB vaccines are currently not readily available in the country. In addition, the NmB gene pool in Africa has not been included in phenotypic assays to determine coverage by globally distributed NmB vaccines. Studies are underway to determine the coverage of various recombinant protein vaccines against NmB based on the current highly variable circulating variants in South Africa.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa (2020–2021), the number of reported IMD cases was lower than prepandemic years but the proportion of peni isolates was higher than other years. Throughout the study period, peni isolates belonged to the same serogroups (NmB and NmW) and lineages (CC213, CC41/44, CC11, and CC22), with no difference between pre- and postpandemic years. Similar to 2000–2005 [13], peni isolates represented a variety of serogroups, lineages, and penA alleles, suggesting independent introduction of these penA genes rather than clonal expansion. The penA9 allele is common in Neisseria lactamica, suggesting horizontal gene transfer between the 2 species [48]. In Europe, penA9 is common in NmW:CC11 peni isolates [14]; only 1 penA9-harbouring peni isolate in our study belonged to NmW:CC11, and the rest were in NmB (unassigned CC) ST8597 and ST16216, and NmY:CC23. However, the other most prevalent penA variant driving peni (penA14) was found in NmW:CC11 and CC22 in our study. Penicillin nonsusceptibility due to β-lactamase activity has not yet been identified in South Africa, in contrast to the United States, Canada, and France [19].

The acquisition of a penA mosaic has been demonstrated to originate from other Neisseria species sharing the oropharyngeal niche [48]. For treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, similar antibiotics are used, and PBP2 is the target for both penicillin and third-generation cephalosporins. Other mutations in PBP2, including I312M, V316T, N512Y, A549T, and A574V, have been associated with reduced susceptibility to penicillin and cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae [49]. Although these mutations were detected in some peni isolates in this study, all were susceptible to ceftriaxone. In China, a peni isolate, harboring penA184, had a single A549T mutation in PBP2 and none of the 5 common mutations known to confer penicillin resistance [50]. Although ciprofloxacin resistance in N. meningitidis is rare in South Africa, other countries such as China have reported ciprofloxacin-resistant strains with a susceptibility rate of 25% in 2005–2019 [22]; the majority were NmA:CC5 and NmB/C:4821 isolates. Ciprofloxacin resistance has also been documented in Europe, South America, the United States, and Canada [22].

Due to loss of viability of cultures, whole-genome sequencing was only performed on N. meningitidis from less than half of laboratory-confirmed IMD cases. Nonetheless, the serogroup distribution was similar among culture-negative samples confirmed and genogrouped by PCR, and isolates serogrouped by phenotypic methods. Targeted whole-genome sequencing from clinical specimens would be useful in generating genomic characterization data for IMD cases without the need for a viable isolate and this methodology is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Despite the ongoing decline in IMD incidence in South Africa, the proportion of peni isolates was higher relative to previous years, although not specifically linked to expansion of any particular lineage. The serogroup distribution was consistent throughout the study period and lineages were also consistent with distributions in preceding years. However, some evolution in the genetic profiles, particularly among NmY strains, and increase in variants detected within the OMPs (PorA:FetA) was noted. Considering that the clinical significance of peni is unclear, and the varied lineages involved, continued use of third-generation cephalosporins can be considered effective in treating confirmed meningococcal disease, including meningitis in South Africa.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Author contributions. R. L. M. contributed conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft, review, and editing. S. M. contributed conceptualization, data interpretation, and writing review and editing. L. d. G. and K. A. J. performed investigations, and writing review and editing. W. Y. C. performed bioinformatics analysis, and writing review and editing. D. V. T., L. H. H., V. Q., C. C., and S. W. contributed writing review and editing. H. M. performed bioinformatics training, and writing review and editing. A. I. performed sequencing, and writing review and editing. A. v. G. contributed conceptualization, data interpretation, and writing review and editing. M. d. P. contributed conceptualization and data interpretation.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank all participants and laboratories throughout South Africa who submit samples and metadata for IMD cases through the GERMS-SA platform; and Shalabh Sharma (US CDC, Atlanta) for assistance with the Bacterial Meningitis Genomic Analysis Platform for genomic characterization.

Disclaimer. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding agents.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, National Health Laboratory Service, South Africa (to GERMS-SA for national, laboratory-based surveillance); US Agency for International Development, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative; and the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health (grant number D43TW011255 Global Infectious Disease Research Training grant to the University of Pittsburgh and the National Institute for Communicable Diseases). Whole gemome sequencing was supported by the SEQAFRICA project, which is funded by the UK Department of Health and Social Care, UK Aid Fleming Fund. PubMLST is supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 218205/Z/19/Z Biomedical Resources Grant).

References

Meiring S, Cohen C, de Gouveia L, et al. GERMS-SA annual surveillance report for laboratory-confirmed invasive meningococcal, Haemophilus influenzae, pneumococcal, group A streptococcal and group B streptococcal infections, South Africa. 2020. https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2020-GERMS-SA-Annual-Review.pdf. Accessed 14 February 2022.

Author notes

Presented in part: 22nd International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 9–14 October 2022, abstract No. 296; and Public Health Alliance of Genomic Epidemiology Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 30 October to 1 November 2023, abstract No. 48.

Potential conflicts of interest. S. M. has participated in an advisory board for GSK for meningococcal B vaccine use in South Africa (no payment or honoraria received); and gave an educational presentation for Sanofi Pasteur at an industry-sponsored symposium at the PASA Conference on Meningitis, South Africa (travel expenses but no honoraria or payment received). K. J. reports a Wellcome Trust Biomedical Resource Grant for PubMLST, paid to the University of Oxford; and database royalties from GSK. L. H. attends scientific advisory boards for Pfizer, Merk, and GSK (no fees paid); and participates on the data safety monitoring board for experimental pneumococcal vaccine for Merck. V. Q. attended the MSD Pediatric Vaccines Symposium, 29–30 September 2023, Warsaw, Poland (no payment received). C. C. has received funding from US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust, South African Medical Research Council, Sanofi Pasteur, and PATH. A. v. G. is the chairperson of the National Advisory Group for Immunisation, South Africa. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.