-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Raul Macias Gil, Jasmine R Marcelin, Brenda Zuniga-Blanco, Carina Marquez, Trini Mathew, Damani A Piggott, COVID-19 Pandemic: Disparate Health Impact on the Hispanic/Latinx Population in the United States, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 222, Issue 10, 15 November 2020, Pages 1592–1595, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa474

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2, emerged in Wuhan, China, causing the coronavirus disease 2019 we now refer to as COVID-19. The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 12 March 2020. In the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed preexisting social and health disparities among several historically vulnerable populations, with stark differences in the proportion of minority individuals diagnosed with and dying from COVID-19. In this article we will describe the emerging disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on the Hispanic/Latinx (henceforth: Hispanic or Latinx) community in the United States, discuss potential antecedents, and consider strategies to address the disparate impact of COVID-19 on this population.

As of 21 May 2020, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected over 5 million people across the globe [1]. In the United States, over 1.5 million people have been infected and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has claimed over 90 000 lives [2]. Pandemics can affect individuals regardless of their background. However, prior pandemics have had heightened adverse effects on vulnerable populations, including racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States [3]. For COVID-19, emerging US data show particular adverse impact of this pandemic on the Latinx community [4, 5].

COVID-19 DATA IN HISPANICS

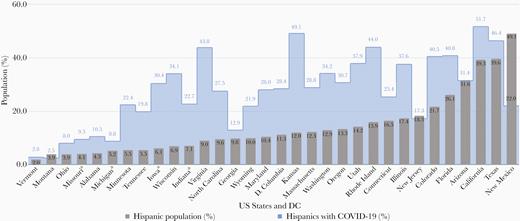

The Hispanic population is the largest ethnic minority group in the United States, comprising nearly 60 million people [6]. Whereas Hispanics constitute 18% of the total US population, this group accounts for 28.4% of cumulative US COVID-19 cases with known ethnicity reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as of 20 May 2020 [2]. As of 20 May, 45 states and the District of Columbia (DC) have released COVID-19 data by race or ethnicity, though only 31 states and DC have reported data among Hispanics [1, 2]. In 27 (87%) of these states, as well as in DC, the percentage of COVID-19 cases identified as Hispanic notably exceed the proportion of Hispanics in the state population (Figure 1).

Percentages of states’ populations who were Hispanic/Latinx and percentages of states’ total COVID-19 cases who were Hispanic/Latinx as of 14 May 2020. Data were obtained from the 2018 US census and each of the states’ departments of health. aPercentage of Hispanics in state’s total COVID-19 cases was calculated excluding persons for whom ethnicity was unknown or not available.

COVID-19 hospitalization data by ethnicity remain limited. The CDC COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), which conducts population-based surveillance for laboratory-confirmed COVID-19-associated hospitalizations across 14 states, found Hispanics comprised 14.2% of hospitalizations [5].

COVID-19 mortality data for the Hispanic population also remain sparse. However, in New York City where the COVID-19 pandemic has exacted one of the highest tolls, both COVID-19–related hospitalization and death rates have been significantly elevated in the Hispanic population compared to Whites—with a 2-fold higher age-adjusted death rate for the Hispanic population (204.6 per 100 000 vs 90.4 per 100 000) as of 14 May 2020 [7].

COVID-19: HEALTH INEQUITY AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH IN THE HISPANIC/LATINX COMMUNITY

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health inequities as avoidable inequalities in health between groups of people within countries and between countries [8]. Conversely, health equity has been defined as the state in which everyone has the opportunity to attain full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance [9]. Racial/ethnic health inequities in the United States have existed as far back as the history of the US territory conquest, evident in statistical data acquired since the founding of colonial America [10–12]. Such inequities find roots in historical and contemporaneous social determinants of health, namely the conditions in the social, physical, and economic environment in which people are born, live, work, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks [13]. The disparate impact of COVID-19 on historically vulnerable populations raises concern for the role of deep-rooted structural health inequities and the potential contribution of pervasive social determinants that long have adversely impacted the health of the Latinx community [11, 12].

Coexisting Medical Conditions

High rates of chronic comorbid disease have been reported among patients with severe COVID-19 infection, with 90% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients having at least 1 underlying chronic disease condition in a recent CDC report [5]. Hispanics have a higher burden and/or suboptimal control of multiple chronic conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes, renal disease) than non-Hispanic whites that may place them at higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes [14, 15].

Access to Healthcare

Hispanics have the lowest rates of medical health insurance coverage of all racial/ethnic groups within the United States, with 19.8% of Hispanics uninsured in 2018 compared to 5.4% of non-Hispanic Whites [15]. Being uninsured or underinsured may pose a significant barrier to access to COVID-19 testing and care. Absence of coverage may further impede prevention and control of the aforementioned chronic comorbid disease conditions associated with severe COVID-19 disease.

Immigration Status

Immigration status also may pose a barrier to COVID-19 care, secondary to fear or mistrust of medical, public health, and other societal institutions, exclusion from insurance coverage eligibility (eg, Medicaid), and limitations of personal financial resource. Both absolute and perceived restrictions to securing essential services and public benefits (eg, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families), even among those legally eligible to receive services, may impede critical access to COVID-19–related care resources for this community [16].

Language Barriers

According to the Office of Minority Health, 72% of Hispanics speak a language other than English at home and 29.8% state that they are not fluent in English [17]. Research shows that language barriers can adversely affect quality of care, and that patients with limited English proficiency have decreased access to care, increased emergency department visits, longer inpatient hospitalizations, and worse clinical outcomes [18]. Language barriers can negatively influence the COVID-19 care continuum from inadequate public health prevention messaging to impaired delivery of accessible language-sensitive inpatient care, potentially made worse by physical distancing and greater patient isolation.

Work Conditions, Financial Burden, and Living and Undomiciled Conditions

Prevailing work and living conditions in the Latinx community may increase both exposure to and acquisition of SARS-CoV2. This population is overrepresented among those providing critical essential services, with a quarter of Hispanics working in key service occupations (eg, ensuring food supply for the general population) [19]. Despite social distancing recommendations and guidance for employees to stay home when sick for COVID-19 prevention, paid sick leave and working from home are not options for all workers across the United States. In prepandemic data, while 31.4% of non-Hispanic workers could telecommute, only 16.2% of Hispanic workers held jobs that would allow them to work from home [20]. The US poverty rate for Hispanics is 19.4% compared to 9.6% for non-Hispanic whites [21]. With marked financial pressures and fear of lost income, persons in Latinx communities currently face a stark dilemma of looking for jobs that may increase their risk of infection or staying home without income. Many Latinx families live in multigenerational homes that may not facilitate adherence to WHO/CDC social distancing/isolation recommendations. Hispanics are overrepresented in other congregate settings including detention centers, prisons, and homeless settings, which also may hinder prevention of COVID-19 exposure and acquisition [22, 23]. Low financial resources further may impede maintaining a reliable supply of medications and food at home, potentially exacerbating uncontrolled chronic comorbid disease associated with COVID-19 disease severity. Ultimately, these compromised work, living, and financial conditions in the Latinx population may significantly increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and poor COVID-19 outcomes.

ADDRESSING COVID-19 DISPARITIES IN THE HISPANIC/LATINX POPULATION

In order to address the emerging disparate impact of COVID-19 on the Latinx community, it will be critical to harness known evidence-based health equity promoting strategies and apply these along the full COVID-19 care continuum from prevention/testing to treatment and care [12, 24].

Strategies in the near term should include:

Prompt, effective, and sustained health communication and outreach to inform COVID-19 prevention efforts in the Latinx population that is linguistically and culturally congruent, sensitive to histories, legacies, prevailing attitudes, and beliefs across this community

Strong engagement and establishment of trust between community partners and healthcare delivery teams directed at ensuring optimal linkage to high-quality care for COVID-19 and the prevention of related comorbid disease

Equitable and full access to SARS-CoV-2 testing when needed for all community members to facilitate effective individual diagnosis and care and to help protect the community at large

Adequate and flexible access to ambulatory and inpatient hospital care for all community members (eg, Medicaid expansion), necessary for effective COVID-19 management

Effective data collection on testing, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths across all states, districts, and territories with sociodemographic delineation to facilitate granular analysis of factors that may contribute to propagation and severity of disease, to inform appropriately targeted individual and community interventions, and to guide the strategic deployment of resources to communities in need.

Conjoined with these strategies must be an intensified and sustained effort to dismantle longstanding social determinants (eg, income, employment, housing, education, and physical and social environment) that have provided fertile ground for the COVID-19 pandemic’s devastating impact on populations long vulnerable to significant health disparities, including the Latinx community.

CONCLUSION

Unprecedented in nature and scope, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the disproportionate preexisting frailty and vulnerability to poor health outcomes of key population groups including the Latinx population. This massive external stressor has strongly underscored that the opportunity to attain full health potential is yet to be afforded to all. As SARS-CoV-2 has spread to all corners of the globe, it has reminded us that we are all inextricably intertwined, and has highlighted with urgency the substantive work that remains to be done to eliminate health disparities and achieve health equity, in order to ultimately maximize positive health outcomes for all.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Dr Maria de Lourdes Enriquez-Macias, Dr Lucia Pruneda-Alvarez, and the staff of the Infectious Diseases Society of America for their assistance with preparing this manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interests. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

This perspective was written on behalf of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity Task Force