-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Davide C Orazi, Tom van Laer, There and Back Again: Bleed from Extraordinary Experiences, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 49, Issue 5, February 2023, Pages 904–925, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac022

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

From reenactments to pilgrimages, extraordinary experiences engage consumers with frames and roles that govern their actions for the duration of the experience. Exploring such extraordinary frames and roles, however, can make the act of returning to everyday life more difficult, a process prior research leaves implicit. The present ethnography of live action role-playing explains how consumers return from extraordinary experiences and how this process differs depending on consumers’ subjectivity. The emic term “bleed” captures the trace that extraordinary frames and roles leave in everyday life. The subjective tension between the extraordinary and the ordinary intensifies bleed. Consumers returning from the same experience can thus suffer different bleed intensities, charting four trajectories of return that differ in their potential for transformation: absent, compensatory, cathartic, and delayed. These findings lead to a transformative recursive process model of bleed that offers new insights into whether, how, and why consumers return transformed from extraordinary experiences with broader implications for experiential consumption and marketing.

I took the hat off, clinging to it all the way home, thinking about being back in this strange, therapeutic, enlightening experience, where the hosts seemed to understand me better than I did. I wanted to go back; despite the small panic attack and emotional exhaustion that washed over me, I wanted to do it all again (Alexander 2017).

Accessing an alternative realm beyond the everyday where they can be someone else has captured consumers’ imagination for centuries. Fascination with utopian worlds and possible selves continues to the present day (Kozinets 2002; Schouten 1991), and consumer experiences with fictional or virtual places offer a new frontier for innovative companies (Bertele et al. 2020). Contemporary consumer society is brimming with opportunities to join extraordinary experiences that allow for the exploration of different settings and roles—from reenacting the fur trade in modern mountain men’s rendezvous (Belk and Costa 1998), to immersion into vampire narratives during the Whitby Goth Weekend (Goulding and Saren 2016), to the decelerated experience that a Camino de Santiago pilgrimage promises (Husemann and Eckhardt 2019).

Returning from such experiences can be challenging. Modern mountain men’s “romantic nostalgia” (Belk and Costa 1998, 233), Whitby Goths’ “trace” (Goulding and Saren 2016, 221), and pilgrims’ “post-Camino syndrome” (Husemann and Eckhardt 2019, 1158) all suggest that coming back to reality is difficult. What this challenge exactly looks like, however, is still a question. How the kinds of lives consumers are leading influences the process of returning from extraordinary experiences also remains underexplored. Previous scholarship examines subjective understandings of consumers’ everyday life mainly as a motivation to engage in the experience (Kozinets 2002; Tumbat and Belk 2011), leaving uncharted how individual differences influence the process of returning. Yet the consequences of experiential consumption are likely as idiosyncratic as its antecedents (Tumbat and Belk 2011). Scholarship thus needs a better understanding of what happens when consumers leave extraordinary experiences and reintegrate into everyday life, and how subjective understandings of the tension between “extraordinary” and “everyday” influence this process.

This article examines the challenge of returning from extraordinary experiences in the context of live action role-play (LARP), an extraordinary experience during which consumers explore fantastic frames within which they assume the roles of invented characters (Orazi and Cruz 2019). Since frames and roles characterize what consumers detach from when returning to everyday life, these Goffmanian (1974) concepts enable us to unpack the emic term “bleed” as the process through which consumers’ experience in the extraordinary seeps into the ordinary, like dye colors bleed into one another. Unpacking bleed is theoretically relevant to advance understanding of the process by which consumers return from extraordinary experiences. As a result, we make three contributions to the literature: We (1) identify the critical dimensions of bleed to provide greater insight into what happens when consumers return from extraordinary experiences; (2) explain how consumers’ subjective understandings of the tension between the extraordinary experience and their everyday lives can influence bleed’s intensity; and (3) formalize a transformative recursive process that captures the diverse trajectories consumers can take when returning from extraordinary experiences.

In the following sections, we offer a conceptual framework that systematically reviews and reinterprets previous research into extraordinary experiences in terms of outcomes of returning, frames and roles with which consumers engage, and sources of tension. We then present our context and methods, after which we undertake an analytical investigation into the types of bleed and chart the trajectories consumers follow when they return from LARPing.

CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

Features and Outcomes of Returning from Extraordinary Experiences

Extraordinary experiences are a “special class of hedonic consumption activities” (Arnould and Price 1993, 25) that share three identifiable features: intensity, engagement, and temporality (Abrahams 1986; Scott, Cayla, and Cova 2017). Intensity refers to the ability of extraordinary experiences to be sensorially and emotionally rich. Take clubbing, for example: “The combination of repetitive electronic music, extended periods spent dancing, and the use of ecstasy can act as a potent means to induce a loss of self, a transcendence of the body” (Goulding et al. 2009, 767). The elicited sensations bear an affinity with intense emotions, which help consumers lose themselves in the experience. Engagement reflects extraordinary experiences’ ability to drag consumers into the experience through a socially constructed frame, as we elaborate below. To walk into an extraordinary experience unexpectedly or be ignorant of the frame can be upsetting, as Goulding and Saren (2016, 219) explain in their study of Whitby Goth Weekend. Two campers who were unaware of the festival had been sleeping in their tent in the town’s graveyard, when around 2 a.m. festivalgoers dressed up as “vampires, sitting amidst the graves, holding candles, fangs glinting in the light, drinking red wine” woke them up with a shock. Fortunately for outsiders then, extraordinary experiences dissolve quite quickly after they form because, while they are generally nonstop, multiday-long events, they do end. Temporality refers to this time-limited nature of extraordinary experiences. Returning from intense and engaging experiences, however, can create disillusion when reentering everyday life.

Consumer research acknowledges instances of maladjustment upon returning. Weekend skydivers (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh 1993, 15) and bikers (Schouten and McAlexander 1995, 45) suffer cravings and “withdrawal” when Monday morning comes around. Modern mountain men feel “romantic nostalgia” for “the fantasy time and place that they visited and helped create” (Belk and Costa 1998, 233). Carnival goers need to face the consequences of their excesses and subversions when the party is over (Weinberger and Wallendorf 2012). Whitby Goth Weekend leaves a “trace” with Goths, and a trace of the Goths is left in Whitby’s culture and economy after the festival (Goulding and Saren 2016, 221). Husemann and Eckhardt (2019, 1158) describe symptoms of “post-Camino syndrome”: confusion, depression, disorientation, emptiness, fear, irritation, panic, purposelessness, and stress. Burners, climbers, Trekkers, surfers, and white-water rafters report similar challenges upon returning to everyday life (table 1).

| Experience . | Frames . | Role(s) . | Challenges from leaving . | Representative article . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning man event | Anglo-Saxon paganism, antimarket discourse, Promethean performances, ethos of connection and fantasy | Recreational, anonymous, decorative, fictional characters | Possibility of illumination of taken-for-granted market logics and flashes of inspiration | Kozinets (2002) |

| Camino de Santiago pilgrimage | Embodied, episodic, and technological deceleration | Modern pilgrim | Post-Camino syndrome: perceived void, disorientation, purposelessness | Husemann and Eckhardt (2019) |

| Chomolungma/Mount Everest climb | Conquest of nature | Modern hero | Competition for individual goals that trump communal goals, even in the case of tragic events | Tumbat and Belk (2011) |

| Harley-Davidson motorcycle rally | Frontier liberty and license | Biker personae that borrow heavily from the Wild West drifter, the western folk hero, and outlaw archetypes | Riding addiction and withdrawal | Martin et al. (2006) and Schouten and McAlexander (1995) |

| Modern mountain men’s rendezvous | The frontier and mountain men myth | Heroic archetypes of buckskinners from the 1800 s Rocky Mountains fur trade | Difficulty of getting back up to speed, “romantic nostalgia” | Belk and Costa (1998) |

| New Orleans’ Mardi Gras | Subversion of ordinary norms | Krewe member pretending to be royalty | Tension between exuberance and pious contemplation | Weinberger and Wallendorf (2012) |

| Skydiving | High-risk activity | Dramatic actor but no distinct persona | Craving and withdrawal | Celsi et al. (1993) |

| Star Trek convention | Star Trek movies and TV series | Star Trek characters | Blurring boundaries between fantasy and reality | Kozinets (2001) |

| Surfing | Romance of sublime, sacred, and/or primitive nature | Romantic surfers but no distinct persona | Betrayals: mismatches of resources and associated social tensions that thwart romantic experiences | Canniford and Shankar (2013) |

| Tough Mudder | Commitment to an intensely painful activity, conquest of obstacles | Mudder | Residual pain, wounds, and other ailments evidence a suffering body | Scott et al. (2017) |

| Whitby Goth Weekend | The vampire myth and Bram Stoker’s Dracula | Goth personae and fantasy characters | Sense of loss and isolation, a trace left by the absence of the experience | Goulding and Saren (2016) |

| White-water rafting | Romance, triumph over natural forces achieved through trust and mutual reliance | Producer of community but no distinct persona | Perceived hit in the face with the routines, noises, and other features of everyday life | Arnould and Price (1993) |

| Experience . | Frames . | Role(s) . | Challenges from leaving . | Representative article . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning man event | Anglo-Saxon paganism, antimarket discourse, Promethean performances, ethos of connection and fantasy | Recreational, anonymous, decorative, fictional characters | Possibility of illumination of taken-for-granted market logics and flashes of inspiration | Kozinets (2002) |

| Camino de Santiago pilgrimage | Embodied, episodic, and technological deceleration | Modern pilgrim | Post-Camino syndrome: perceived void, disorientation, purposelessness | Husemann and Eckhardt (2019) |

| Chomolungma/Mount Everest climb | Conquest of nature | Modern hero | Competition for individual goals that trump communal goals, even in the case of tragic events | Tumbat and Belk (2011) |

| Harley-Davidson motorcycle rally | Frontier liberty and license | Biker personae that borrow heavily from the Wild West drifter, the western folk hero, and outlaw archetypes | Riding addiction and withdrawal | Martin et al. (2006) and Schouten and McAlexander (1995) |

| Modern mountain men’s rendezvous | The frontier and mountain men myth | Heroic archetypes of buckskinners from the 1800 s Rocky Mountains fur trade | Difficulty of getting back up to speed, “romantic nostalgia” | Belk and Costa (1998) |

| New Orleans’ Mardi Gras | Subversion of ordinary norms | Krewe member pretending to be royalty | Tension between exuberance and pious contemplation | Weinberger and Wallendorf (2012) |

| Skydiving | High-risk activity | Dramatic actor but no distinct persona | Craving and withdrawal | Celsi et al. (1993) |

| Star Trek convention | Star Trek movies and TV series | Star Trek characters | Blurring boundaries between fantasy and reality | Kozinets (2001) |

| Surfing | Romance of sublime, sacred, and/or primitive nature | Romantic surfers but no distinct persona | Betrayals: mismatches of resources and associated social tensions that thwart romantic experiences | Canniford and Shankar (2013) |

| Tough Mudder | Commitment to an intensely painful activity, conquest of obstacles | Mudder | Residual pain, wounds, and other ailments evidence a suffering body | Scott et al. (2017) |

| Whitby Goth Weekend | The vampire myth and Bram Stoker’s Dracula | Goth personae and fantasy characters | Sense of loss and isolation, a trace left by the absence of the experience | Goulding and Saren (2016) |

| White-water rafting | Romance, triumph over natural forces achieved through trust and mutual reliance | Producer of community but no distinct persona | Perceived hit in the face with the routines, noises, and other features of everyday life | Arnould and Price (1993) |

| Experience . | Frames . | Role(s) . | Challenges from leaving . | Representative article . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning man event | Anglo-Saxon paganism, antimarket discourse, Promethean performances, ethos of connection and fantasy | Recreational, anonymous, decorative, fictional characters | Possibility of illumination of taken-for-granted market logics and flashes of inspiration | Kozinets (2002) |

| Camino de Santiago pilgrimage | Embodied, episodic, and technological deceleration | Modern pilgrim | Post-Camino syndrome: perceived void, disorientation, purposelessness | Husemann and Eckhardt (2019) |

| Chomolungma/Mount Everest climb | Conquest of nature | Modern hero | Competition for individual goals that trump communal goals, even in the case of tragic events | Tumbat and Belk (2011) |

| Harley-Davidson motorcycle rally | Frontier liberty and license | Biker personae that borrow heavily from the Wild West drifter, the western folk hero, and outlaw archetypes | Riding addiction and withdrawal | Martin et al. (2006) and Schouten and McAlexander (1995) |

| Modern mountain men’s rendezvous | The frontier and mountain men myth | Heroic archetypes of buckskinners from the 1800 s Rocky Mountains fur trade | Difficulty of getting back up to speed, “romantic nostalgia” | Belk and Costa (1998) |

| New Orleans’ Mardi Gras | Subversion of ordinary norms | Krewe member pretending to be royalty | Tension between exuberance and pious contemplation | Weinberger and Wallendorf (2012) |

| Skydiving | High-risk activity | Dramatic actor but no distinct persona | Craving and withdrawal | Celsi et al. (1993) |

| Star Trek convention | Star Trek movies and TV series | Star Trek characters | Blurring boundaries between fantasy and reality | Kozinets (2001) |

| Surfing | Romance of sublime, sacred, and/or primitive nature | Romantic surfers but no distinct persona | Betrayals: mismatches of resources and associated social tensions that thwart romantic experiences | Canniford and Shankar (2013) |

| Tough Mudder | Commitment to an intensely painful activity, conquest of obstacles | Mudder | Residual pain, wounds, and other ailments evidence a suffering body | Scott et al. (2017) |

| Whitby Goth Weekend | The vampire myth and Bram Stoker’s Dracula | Goth personae and fantasy characters | Sense of loss and isolation, a trace left by the absence of the experience | Goulding and Saren (2016) |

| White-water rafting | Romance, triumph over natural forces achieved through trust and mutual reliance | Producer of community but no distinct persona | Perceived hit in the face with the routines, noises, and other features of everyday life | Arnould and Price (1993) |

| Experience . | Frames . | Role(s) . | Challenges from leaving . | Representative article . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning man event | Anglo-Saxon paganism, antimarket discourse, Promethean performances, ethos of connection and fantasy | Recreational, anonymous, decorative, fictional characters | Possibility of illumination of taken-for-granted market logics and flashes of inspiration | Kozinets (2002) |

| Camino de Santiago pilgrimage | Embodied, episodic, and technological deceleration | Modern pilgrim | Post-Camino syndrome: perceived void, disorientation, purposelessness | Husemann and Eckhardt (2019) |

| Chomolungma/Mount Everest climb | Conquest of nature | Modern hero | Competition for individual goals that trump communal goals, even in the case of tragic events | Tumbat and Belk (2011) |

| Harley-Davidson motorcycle rally | Frontier liberty and license | Biker personae that borrow heavily from the Wild West drifter, the western folk hero, and outlaw archetypes | Riding addiction and withdrawal | Martin et al. (2006) and Schouten and McAlexander (1995) |

| Modern mountain men’s rendezvous | The frontier and mountain men myth | Heroic archetypes of buckskinners from the 1800 s Rocky Mountains fur trade | Difficulty of getting back up to speed, “romantic nostalgia” | Belk and Costa (1998) |

| New Orleans’ Mardi Gras | Subversion of ordinary norms | Krewe member pretending to be royalty | Tension between exuberance and pious contemplation | Weinberger and Wallendorf (2012) |

| Skydiving | High-risk activity | Dramatic actor but no distinct persona | Craving and withdrawal | Celsi et al. (1993) |

| Star Trek convention | Star Trek movies and TV series | Star Trek characters | Blurring boundaries between fantasy and reality | Kozinets (2001) |

| Surfing | Romance of sublime, sacred, and/or primitive nature | Romantic surfers but no distinct persona | Betrayals: mismatches of resources and associated social tensions that thwart romantic experiences | Canniford and Shankar (2013) |

| Tough Mudder | Commitment to an intensely painful activity, conquest of obstacles | Mudder | Residual pain, wounds, and other ailments evidence a suffering body | Scott et al. (2017) |

| Whitby Goth Weekend | The vampire myth and Bram Stoker’s Dracula | Goth personae and fantasy characters | Sense of loss and isolation, a trace left by the absence of the experience | Goulding and Saren (2016) |

| White-water rafting | Romance, triumph over natural forces achieved through trust and mutual reliance | Producer of community but no distinct persona | Perceived hit in the face with the routines, noises, and other features of everyday life | Arnould and Price (1993) |

While these contributions acknowledge challenges, they do not explain how these challenges filter back into everyday life and to what effect (Kozinets 2002). Understanding this process would require conceptualizing the critical dimensions of the experience that extend into everyday life. In the next section, we review literature on classes of hedonic consumption that are not necessarily extraordinary experiences to gain insight into these dimensions of consumers’ returns and readjustments.

Critical Dimensions of Returning from Hedonic Consumption

As previously mentioned, extraordinary experiences are a special class of hedonic consumption, so we scoured the literature for studies addressing returns and readjustments from adjoining hedonic consumption classes, including instore shopping (Borghini, Sherry, and Joy 2021), virtual reality (VR; Smahel, Blinka, and Ledabyl 2008), and narratives (van Laer et al. 2019). Though diverse, the problem of returning and adjusting transcends these classes. They converge on the sources of the challenge: leaving a physical, virtual, or imagined setting (Fine 2002) and the role consumers occupy within it (Seregina 2019).

Spectacular retail spaces, such as Nike Town, make visitors feel “transported to another place, an otherworldly site inhabited by super[humans]” (Peñaloza 1998, 380). As part of such experiences, consumers get emotionally attached to places and ascribe meaning to them (Debenedetti, Oppewal, and Arsel 2014). When forced to detach from meaningful retail environments, consumers can “lose … a link to a meaningful past,” as their so-called “displacement” takes away a possibility for future self-transformation (Borghini et al. 2021, 893).

Additionally, the video-gaming literature discusses detachment from characters. In massive multiplayer online role-playing games, players journey into virtual worlds using avatar-characters with whom they form intense emotional connections (Linderoth 2012). Avatar-characters serve as a means to explore fantastic and/or idealized selves in alternate realities (Miao et al. 2022), leading to a player-character identity overlap termed “character attachment” (Lewis, Weber, and Bowman 2008). This attachment can produce withdrawal symptoms and identity issues after the activity ends (Smahel et al. 2008).

In literary studies, transportation theory proposes that consumers travel some distance from their world of origin through stories (Gerrig 1993). Transportation requires mental imagery of the narrative world and empathy with its characters (for a meta-analysis, see van Laer et al. 2014). Returning from the narrative world can be transformative (Phillips and McQuarrie 2010) as long as the narrative world is not too distant from reality.

In summary, different research streams on hedonic consumption suggest three key insights into challenging returns: (1) consumers detach from specific frames; (2) in which they explored certain roles; and (3) detachment becomes more challenging the more consumers feel a tension between the experience and everyday life. An interpretative framework that demystifies the process of return must thus deconstruct the frames that set the stage for extraordinary action and exploration of extraordinary roles, while explaining why detachment triggers distress. We find in Goffman’s (1974) concepts of frames, roles, and upkeying the building blocks to lay the foundation for such a framework.

Extraordinary Frames and Roles

The concept of frame determines a critical dimension of consumers’ engagement in extraordinary experiences, specifically their attachment to the setting (Fine 2002) or space (Borghini et al. 2021). Frames are situational definitions “constructed in accord with organizing principles that govern both the events themselves and participants’ experience of these events” (Goffman 1974, 10–11). A frame thus details shared beliefs, norms, and values that set down what to find, specify how to behave, and stipulate what things mean in a specific situation. Consumers navigate everyday life using ordinary frames that set the rules of acceptable conduct in the natural and social worlds. These ordinary frames, which are already meaningful by themselves, can change into something consumers will perceive as different by adding layers of “keyed” frames.

Engagement in extraordinary experiences thus requires participants to layer more “extraordinary frames” that add to or change the normative prescriptions of ordinary frames. Frames vary in their degree of “upkeying,” or the extent that layering them “increases [the] distance from what we would call literal reality” (Goffman 1974, 366). Some add elements of dramatic performance to the acts of rafting (Arnould and Price 1993), skydiving (Celsi et al. 1993), and obstacle-racing (Scott et al. 2017). Others prescribe entire, complex systems that transform everyday life into alternative realms (Goulding and Saren 2016). The latter frames lead to Burners’ liberation and creative self-expression (Kozinets 2002), dictate acceptable reenactment practices to modern mountain men (Belk and Costa 1998), and let geeks travel to a post-capitalist utopia set 300 years in the future (Kozinets 2001). The sources of such greatly upkeying frames are often narrative in nature (van Laer, Visconti, and Feiereisen 2018), such as Roddenberry’s science-fiction writing and productions for Star Trek conventions (Kozinets 2001) and Stoker’s (1897/1992) Dracula novel for the Whitby Goth Weekend (Goulding and Saren 2016). When layered onto ordinary frames, these extraordinary frames offer mutual understanding to direct participants’ actions during the experience.

Beyond setting the normative stage for a situation, frames prescribe roles—namely, what is expected of a person in a particular frame (Goffman 1974). Roles shape individuals’ identity, or the understanding of who they are as they define their subjective reality in respect of the relevant frame (Williams, Hendricks, and Winkler 2006). Consumer research acknowledges that individuals do not have strict identities (Appau, Ozanne, and Klein 2020; Schouten 1991; Seregina and Schouten 2017) but perform roles according to the referenced frames, continuously remixing the resulting self-understandings to construct an individual identity (Seregina 2019).

Since frames prescribe roles, they vary in their degree of upkeying too. Extraordinary experiences often offer the opportunity to take on a role that further contributes to the detachment from everyday life. Some roles can archetypically define what participants will do during the experience, such as walking the Camino as pilgrims (Husemann and Eckhardt 2019), posing as krewe royalty in a carnival (Weinberger and Wallendorf 2012), or conquering natural and artificial obstacles as modern heroes (Arnould and Price 1993; Scott et al. 2017; Tumbat and Belk 2011). Other extraordinary roles transcend the archetypical to present complete characters for consumers to adopt, such as Captain America at a comic book convention (Seregina and Weijo 2016), Goth Morris dancer during Whitby Goth Weekend (Goulding and Saren 2016), or Spock at a Star Trek convention (Kozinets 2001). Such roles experienced in the extraordinary contribute to the state of detachment from ordinary life and allow consumers to explore their fantastic selves (Schouten 1991).

In summary, frames and roles are two critical dimensions of engagement with the extraordinary that capture what consumers separate from when returning to the ordinary. While we do not employ Goffmanian (1974) frame analysis in our ethnography per se, we use his conceptualization of frames, roles, and upkeying to elucidate our data and characterize the critical dimensions of returning from the extraordinary. Table 1 summarizes the challenge of returning and provides a reinterpretation of engagement with extraordinary experiences documented by prior research.

Tensions between Extraordinary and Ordinary Frames and Roles

During extraordinary experiences, consumers “leave behind their normal values, beliefs, and customs” (Goulding and Saren 2016, 220). They become less reflexive of their ordinary frames and roles as extraordinary ones are layered upon them. The more an experience’s frames and roles are thus “upkeyed,” the more they allow a departure from subjectively understood reality (Seregina and Schouten 2017). Even only for a brief time, this distance liberates consumers from the societal constraints imposed on their world and roles (Kozinets 2002), enabling the exploration of alternative perspectives and selves (Belk and Costa 1998; Orazi and Cruz 2019). When the experience inevitably ends, however, the extraordinary layer dissolves and any built-up tension between ordinary and extraordinary frames and roles becomes hard to ignore.

Returning to everyday life may thus result in a rude awakening if the extraordinary frames and roles put consumers under tension as the extraordinary experience drops away. Prior research shows that individual conceptions of ordinary life are clear motivations to take part in an extraordinary experience (Cova, Carù, and Cayla 2018). Bikers long to leave unfulfilling work behind (Schouten and McAlexander 1995), modern mountain men unstable city life (Belk and Costa 1998), Trekkers the prejudice against daydreaming and fantasizing (Kozinets 2001), and Burners the unworthy market (Kozinets 2002). Whether individual differences in ordinary life conceptions influence how difficult consumers find dealing with the return, however, remains unclear. The subjective tension between extraordinary and ordinary frames and roles may be the crux to resolve the challenging return from extraordinary experiences.

In summary, extraordinary experiences are not only intense and temporal, but also engaging (Abrahams 1986; Scott et al. 2017) and they differ in terms of the extraordinary frames and roles they construct to engage consumers. Returning from extraordinary experiences whose frames govern remote worlds and removed selves may be more challenging than currently understood, particularly if consumers feel a tension with daily life. As most consumer research leaves implicit what happens when people leave extraordinary experiences and whether differences between individual consumers influence this process, we ask two fundamental questions: what is the process of returning from an extraordinary experience, and how does the return differ between consumers? To answer these questions, we analyze LARP.

CONTEXT OF STUDY: LARP

LARP refers to collective “performances that take place between imagination and embodied reality” (Seregina 2014, 19) during which consumers assume the role of a character while improvising a plot in a designated theatrical space and time (Orazi and Cruz 2019; Seregina 2019). We chose to investigate LARP as a representative context for three reasons: They are (1) extraordinary experiences, (2) governed by upkeyed frames and roles, and (3) challenging to leave.

First, while LARPs are considered games in popular press and sociology (Fine 2002; Williams et al. 2006), we view them as extraordinary experiences. In contrast with tabletop and video games, LARPs possess the defining features of extraordinary experiences: intensity, engagement, and temporality (Abrahams 1986; Scott et al. 2017). While consumers may get emotional when playing tabletop and video games, neither involves all the physical senses. At most, gamers put cards on a table or use controllers to decide the outcome of skirmishes with strange creatures. By contrast, LARPs involve telling a story both emotionally and multisensorially. They also allow more engagement than is possible with other types of games. The options open to tabletop and video gamers are limited, as it is the game designer, not the game player, who is “writing the book” (Fine 2002, 59). Conversely, LARPs give consumers more agency within their comparably loose confines. The temporality of LARPs also differs from these other games. While consumers can return to tabletop or video games anytime for as long as they want, LARPs are bound to a specific time and schedules. (See web appendix A for more details on the validation of this interpretation.)

Second, LARPs are enabled by accessing distinctive frames and roles. LARPs “entail character immersion and story engagement; hence, costumes are supportive performance elements and their quality is secondary to the story line and/or the interaction” (Seregina and Weijo 2016, 142). LARPers do not only embody characters like cosplayers do, but also embed them in their world constructed as part of the interaction between the characters.

Third, LARPers may find returning to reality difficult. Their constructive efforts are a unique part of a deep immersion into extraordinary frames and roles. Though extraordinary, this experience is lifelike, a characteristic that may present not only a challenge but also the potential for transformation; for example, in the form of skills that can be put to work in more mundane contexts (e.g., improvization skills, Mannucci, Orazi, and de Valck 2021).

METHOD

We approached the field with the aim of understanding the requirements for and consumers’ return from extraordinary experiences. To bolster the integrity of our interpretations, we triangulated our data across multiple ethnographic techniques and constantly checked our developing theory against new data, consistent with a theoretical sampling strategy (Goulding 2002). We began with an archival data collection of Monitor Celestra, a science-fiction LARP enabled by the TV series Battlestar Galactica and constructed by 389 participants in Gothenburg, Sweden, over three runs of three days each in 2013. The LARP revolved around a spaceship that the TV series had not covered. In the words of the designers, the LARP studio company Alternaliv AB, “This is the true story of the 13th Cylon model and the real reason the universe finally found peace, a story you can never watch or read. It’s a story you must live” (alternaliv.se). We expanded this probe with newspaper and web archives analyses of two more LARPs: Fairweather Manor (2015), based on the show Downtown Abbey, and College of Wizardry (2016), based on Harry Potter. This exploratory data set confirmed our intuition that a LARP is indeed an intense, engaging, temporally limited (and therefore extraordinary) experience that lets consumers explore extraordinary frames and roles. Our initial insight having passed muster, we followed up with a search for field sites.

Field Sites

As a first field site, we selected Dracarys 2016, a LARP of the fantasy genre based on the Game of Thrones novels and TV series. Terre Spezzate, a community born “from a small group of enthusiasts,” designs the LARP (events.grv.it/en). Set after season five, the designers invited “nobles and travelers” to celebrate the reconstruction of Summerhall fortress. We chose Dracarys 2016 because the fantasy genre is the most popular frame source for LARPs (Bowman 2010) and the 11-month period between character role assignment in September 2015 and mise-en-scène in August 2016 allowed for a pilot survey and netnography of the preparatory phases. As our first interviews indicated that participants find withdrawing from the experience particularly challenging, we refocused our research program to zoom in on the difficult departures from extraordinary experiences.

The second field site selected was Conscience, a science-fiction LARP based on the Westworld TV series. The event was designed by Not Only Larp, an organization that believes in LARP’s “potential to raise awareness and inspire social change” (notonlylarp.com). Conscience was set in a futuristic amusement park that robot hosts look after. Park guests could indulge their every wish without consequences. We chose Conscience because science fiction is the second most popular LARP genre (Bowman 2010), and Conscience’s theme allowed us to question how adopting countercultural norms and deviant behavior affects the transition from extraordinary experience to ordinary life.

As a third field site, we selected Demetra, again designed by Terre Spezzate. The LARP was not based on a specific TV series and portrayed an alternative reality in which traditional gender roles were reversed and a private company controlled the global food market. This third field site was thus ideal to unpack the tensions between (extra)ordinary frames and roles further.

As a fourth and final field site, we selected Dracarys 2019, a rerun of Dracarys 2016, to ask returning participants to comment on their repeat experience and perform member checks. In summary, we selected our field sites to capture variance. Table 2 breaks down the four field sites in more detail.

| Field site and year . | Location . | Frames . | Roles . | Duration (hours) . | Participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dracarys (2016) | Gazzola, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 330 |

| Conscience (2018) | Tabernas, Spain | Pop-culture western/science fiction, futurism, lawlessness, Westworld lore | Host (robots), park guest, park security, plot writing team, hero, villain | 60 | 85 |

| Demetra (2019) | Cesana Torinese, Italy | Dystopian and spy fiction, gender role reversal | Administrator, corporate, entertainer, gladiator, guest, security, spy, terrorist | 42 | 78 |

| Dracarys (2019) | San Pietro in Cerro, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 204 |

| Field site and year . | Location . | Frames . | Roles . | Duration (hours) . | Participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dracarys (2016) | Gazzola, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 330 |

| Conscience (2018) | Tabernas, Spain | Pop-culture western/science fiction, futurism, lawlessness, Westworld lore | Host (robots), park guest, park security, plot writing team, hero, villain | 60 | 85 |

| Demetra (2019) | Cesana Torinese, Italy | Dystopian and spy fiction, gender role reversal | Administrator, corporate, entertainer, gladiator, guest, security, spy, terrorist | 42 | 78 |

| Dracarys (2019) | San Pietro in Cerro, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 204 |

| Field site and year . | Location . | Frames . | Roles . | Duration (hours) . | Participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dracarys (2016) | Gazzola, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 330 |

| Conscience (2018) | Tabernas, Spain | Pop-culture western/science fiction, futurism, lawlessness, Westworld lore | Host (robots), park guest, park security, plot writing team, hero, villain | 60 | 85 |

| Demetra (2019) | Cesana Torinese, Italy | Dystopian and spy fiction, gender role reversal | Administrator, corporate, entertainer, gladiator, guest, security, spy, terrorist | 42 | 78 |

| Dracarys (2019) | San Pietro in Cerro, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 204 |

| Field site and year . | Location . | Frames . | Roles . | Duration (hours) . | Participants . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dracarys (2016) | Gazzola, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 330 |

| Conscience (2018) | Tabernas, Spain | Pop-culture western/science fiction, futurism, lawlessness, Westworld lore | Host (robots), park guest, park security, plot writing team, hero, villain | 60 | 85 |

| Demetra (2019) | Cesana Torinese, Italy | Dystopian and spy fiction, gender role reversal | Administrator, corporate, entertainer, gladiator, guest, security, spy, terrorist | 42 | 78 |

| Dracarys (2019) | San Pietro in Cerro, Italy | Pop-culture fantasy, Game of Thrones lore, magic, medieval times | Assassin, builder, cleric, knight, mage, noble, outlaw, peasant, politician, sage | 48 | 204 |

Ethnographic Techniques

The final research program included newspaper and web archives, a pilot survey, participant observation, collection of audiovisual materials, post-LARP interviews, consumer diaries, and netnography. We detail these techniques and the data next and in table 3.

| Ethnographic technique . | Field site . | Data . | Purpose . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newspaper and web archives | N/A | 9 newspaper and 11 website articles (respectively 24 and 67 double-spaced pages) | Establishing features and foundations of the experience |

| Pilot survey | Dracarys 2016 | 32 respondents (53 double-spaced pages) | Understanding participants’ profiles and their motivations to take part in the experience |

| Participant observation | All four sites | 198 hours; field notes (52 double-spaced pages) | Developing an intimate understanding of the experience |

| Audiovisual materials | Photos from all four sites; videos from Conscience | 2,496 photos; GoPro videos (4 hours; point of view) | Recording the naturalistic observation of the experience |

| Interviews | All four sites | 29 transcripts (308 double-spaced pages) | Documenting participants’ preparation for, participation in, and aftermath of the experience |

| Consumer diaries | Conscience | Seven diaries (50 double-spaced pages) | Delving deeper into the meaning participants ascribed to the challenge because of the experience |

| Netnography | Dracarys 2016, Conscience, and Demetra | 2,936 screenshot pages | Documenting life before the experience, becoming familiar with emic terms and their use, recording participant postexperience (inter)actions |

| Ethnographic technique . | Field site . | Data . | Purpose . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newspaper and web archives | N/A | 9 newspaper and 11 website articles (respectively 24 and 67 double-spaced pages) | Establishing features and foundations of the experience |

| Pilot survey | Dracarys 2016 | 32 respondents (53 double-spaced pages) | Understanding participants’ profiles and their motivations to take part in the experience |

| Participant observation | All four sites | 198 hours; field notes (52 double-spaced pages) | Developing an intimate understanding of the experience |

| Audiovisual materials | Photos from all four sites; videos from Conscience | 2,496 photos; GoPro videos (4 hours; point of view) | Recording the naturalistic observation of the experience |

| Interviews | All four sites | 29 transcripts (308 double-spaced pages) | Documenting participants’ preparation for, participation in, and aftermath of the experience |

| Consumer diaries | Conscience | Seven diaries (50 double-spaced pages) | Delving deeper into the meaning participants ascribed to the challenge because of the experience |

| Netnography | Dracarys 2016, Conscience, and Demetra | 2,936 screenshot pages | Documenting life before the experience, becoming familiar with emic terms and their use, recording participant postexperience (inter)actions |

| Ethnographic technique . | Field site . | Data . | Purpose . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newspaper and web archives | N/A | 9 newspaper and 11 website articles (respectively 24 and 67 double-spaced pages) | Establishing features and foundations of the experience |

| Pilot survey | Dracarys 2016 | 32 respondents (53 double-spaced pages) | Understanding participants’ profiles and their motivations to take part in the experience |

| Participant observation | All four sites | 198 hours; field notes (52 double-spaced pages) | Developing an intimate understanding of the experience |

| Audiovisual materials | Photos from all four sites; videos from Conscience | 2,496 photos; GoPro videos (4 hours; point of view) | Recording the naturalistic observation of the experience |

| Interviews | All four sites | 29 transcripts (308 double-spaced pages) | Documenting participants’ preparation for, participation in, and aftermath of the experience |

| Consumer diaries | Conscience | Seven diaries (50 double-spaced pages) | Delving deeper into the meaning participants ascribed to the challenge because of the experience |

| Netnography | Dracarys 2016, Conscience, and Demetra | 2,936 screenshot pages | Documenting life before the experience, becoming familiar with emic terms and their use, recording participant postexperience (inter)actions |

| Ethnographic technique . | Field site . | Data . | Purpose . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newspaper and web archives | N/A | 9 newspaper and 11 website articles (respectively 24 and 67 double-spaced pages) | Establishing features and foundations of the experience |

| Pilot survey | Dracarys 2016 | 32 respondents (53 double-spaced pages) | Understanding participants’ profiles and their motivations to take part in the experience |

| Participant observation | All four sites | 198 hours; field notes (52 double-spaced pages) | Developing an intimate understanding of the experience |

| Audiovisual materials | Photos from all four sites; videos from Conscience | 2,496 photos; GoPro videos (4 hours; point of view) | Recording the naturalistic observation of the experience |

| Interviews | All four sites | 29 transcripts (308 double-spaced pages) | Documenting participants’ preparation for, participation in, and aftermath of the experience |

| Consumer diaries | Conscience | Seven diaries (50 double-spaced pages) | Delving deeper into the meaning participants ascribed to the challenge because of the experience |

| Netnography | Dracarys 2016, Conscience, and Demetra | 2,936 screenshot pages | Documenting life before the experience, becoming familiar with emic terms and their use, recording participant postexperience (inter)actions |

Newspaper and Web Archives

We searched the archives for the keywords “LARP,” “live action,” “role-playing,” “television series,” and “TV series” in the global news aggregators and databases Factiva, Google News, and ProQuest and collected the nine newspaper and 11 web articles covering the Monitor Celestra (2013), Fairweather Manor (2015), and College of Wizardry (2016) LARPs. Adopting a bottom-up, inductive approach, we conducted a common discourse analysis of repeated readings and annotations of our data (van Laer and Izberk-Bilgin 2019) to identify the common features and foundations of LARPs.

Pilot Survey

We conducted an online, pre-LARP survey with 32 prospective participants in Dracarys 2016. On the Facebook page dedicated to the LARP, we posted a link to six open-ended questions (see web appendix B). This pilot survey helped us understand participants’ profile, their relationship with the lore informing the extraordinary frame (Game of Thrones), and their expectations of the LARP.

Participant Observation

In contrast with other dramatic contexts, such as theater (Goulding and Saren 2016) or reenactment (Belk and Costa 1998), LARP does not typically allow an audience, so the role of external observer is not permitted. The first author conducted the ethnographic fieldwork instead as a participant in all four field sites. Like extant ethnographies of extraordinary experiences (Arnould and Price 1993; Husemann and Eckhardt 2019), he used his body as a tool for inquiry and knowledge, engaging in a self-witnessing exercise as he constructed and acted alongside other participants.

Audiovisual Materials

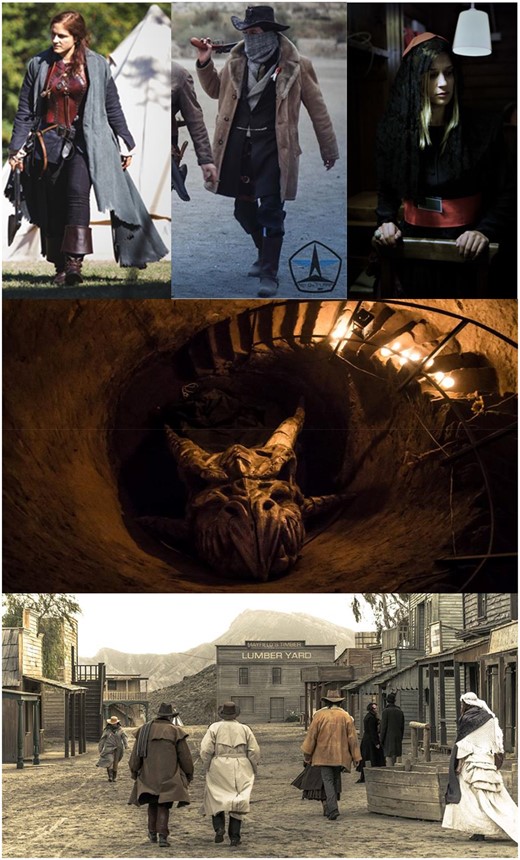

These materials included photos consumers posted online, photos we took, and GoPro videos taped from the first author’s point of view. With permission from the designers, we filmed during Conscience, as the GoPro camera hidden in the first author’s hat was consistent with the science-fiction genre. Photos by consumers enabled a more complete representation and understanding of how the stories of the LARPs were told (Farace et al. 2017). These materials visualized how the setting and scenography, costumes and props help layering extraordinary frames and roles, respectively (see figure 1 and web appendices C and D).

FRAMES AND ROLES VISUALIZED

From top to bottom (photo credits appear in parentheses): characters from Dracarys (Luca Tenaglia), Conscience (Not Only Larp), and Demetra (Nicoló Capello); scenography from Dracarys (Luca Tenaglia); setting of Conscience (PictureTime).

Interviews

In the post-LARP phase we interviewed participants who we recruited via purposive sampling. None of them had completed the pilot survey. We conducted interviews with 11 Dracarys 2016, six Conscience, five Demetra, and seven Dracarys 2019 participants before theoretical saturation. Twenty-one interviewees identify as female. As LARP, similar to cosplay, can be a form of legitimization (Seregina and Weijo 2016), and two of the field sites dealt with either the dynamics of humanity and abuse (Conscience) or the reversal of patriarchy (Demetra), we suspect female participants may have been more prone to accept interview requests to voice their views on a traditionally male-dominated field. All interviewees are between 20 and 59 years of age. Half our sample is Italian, with the rest being mostly from other European countries. Most interviewees are middle-class. The interviews lasted between 30 and 96 minutes, and we conducted them either face-to-face or via videoconferencing. We used a semistructured interview approach guided by the field notes and conducted the interviews in English or Italian. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded for analytical themes. We twice interviewed four participants from Dracarys 2016 and four from Conscience, four and two years after the respective LARPs, to conduct member checks of the emerging framework and glean deeper insights into their post-experience lives.

Consumer Diaries

Seven participants in Conscience chronicled for us their feelings during the week after their LARP. We had previously interviewed three of them. The interviewees used a simple free-form logbook made in Microsoft Word to note specific LARP-related feelings, thoughts, comments, or observations on “Day 1,” “Day 2,” etcetera, which were the sole time cues. They wrote freely and needed neither probing nor prompting. Diaries helped us grasp the challenges that returning from the extraordinary experience presented to participants, a “present” which intruded into mundane consciousness and even dreams. Table 4 offers a summary of our interviewees and diary keepers.

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Nationality . | Occupation . | Field site . | Motivation for participating . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arya | 30 | Italian | Salesperson, actor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Cersei | 30 | Italian | Teacher | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Daenerys | 29 | Russian | Magazine editor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Gilly | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Try a new experience |

| Jaime | 43 | Italian | Salesperson | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Margaery | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Melisandre | 20 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; carving her own story out of the Game of Thrones universe |

| Samwell | 28 | Italian | Architect | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; fan of LARP in general |

| Theon | 38 | Italian | Performing artist | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; designers’ reputation |

| Thoros | 43 | Italian | Financial consultant | Dracarys 2016 | Designers’ reputation; taking part in an epic, massive LARP |

| Ygritte | 47 | Italian | Clerk | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Ashley | 44 | Scottish | IT manager | Conscience | Experience objectification and dehumanization by playing a robot host |

| Caleb | 31 | Italian | Salesperson | Conscience | Fan of LARP in general; helping staff the LARP |

| Dolores | 38 | Norwegian | Game designer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; fan of immersive game experiences |

| Elsie | 33 | Norwegian | Policy advisor | Conscience | Explore what makes us human |

| Emily | 28 | Spanish | Microbiologist | Conscience | Fan of science fiction in general; fan of LARP; explore more mature themes |

| Lauren | 59 | Danish | Museum education officer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; explore ethical dilemmas |

| Maling | 35 | Swedish | Psychologist | Conscience | Fan of Westworld |

| Robert | 35 | Spanish | Actor | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Teddy | 30 | Swiss | Entrepreneur | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Theresa | 36 | Austrian | Web developer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Arion | 37 | German | IT manager | Demetra | Gender role reversal; fan of LARP; try an international experience |

| Despoina | 33 | Italian | Teacher | Demetra | Gender role reversal |

| Hecate | 32 | Swiss | Biomedical scientist | Demetra | Fan of spy fiction; fan of LARP |

| Iacchus | 36 | Italian | Psychologist | Demetra | Fan of LARP; extended romantic date with partner |

| Kora | 35 | Belgian | Communications officer | Demetra | Gender role reversal; setting of the LARP |

| Catelyn | 27 | Italian | Waiter | Dracarys 2016; 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones (2016); staff member at Terre Spezzate (2019) |

| Jon | 33 | American | Retail manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

| Missandei | 28 | Italian | Childcare worker | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; medieval times frame of the LARP |

| Olenna | 45 | Italian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Sansa | 47 | Irish | Translator | Dracarys 2019 | Unfinished storylines from Dracarys 2016 |

| Shae | 31 | Russian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Varys | 34 | Italian | IT manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Nationality . | Occupation . | Field site . | Motivation for participating . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arya | 30 | Italian | Salesperson, actor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Cersei | 30 | Italian | Teacher | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Daenerys | 29 | Russian | Magazine editor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Gilly | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Try a new experience |

| Jaime | 43 | Italian | Salesperson | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Margaery | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Melisandre | 20 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; carving her own story out of the Game of Thrones universe |

| Samwell | 28 | Italian | Architect | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; fan of LARP in general |

| Theon | 38 | Italian | Performing artist | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; designers’ reputation |

| Thoros | 43 | Italian | Financial consultant | Dracarys 2016 | Designers’ reputation; taking part in an epic, massive LARP |

| Ygritte | 47 | Italian | Clerk | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Ashley | 44 | Scottish | IT manager | Conscience | Experience objectification and dehumanization by playing a robot host |

| Caleb | 31 | Italian | Salesperson | Conscience | Fan of LARP in general; helping staff the LARP |

| Dolores | 38 | Norwegian | Game designer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; fan of immersive game experiences |

| Elsie | 33 | Norwegian | Policy advisor | Conscience | Explore what makes us human |

| Emily | 28 | Spanish | Microbiologist | Conscience | Fan of science fiction in general; fan of LARP; explore more mature themes |

| Lauren | 59 | Danish | Museum education officer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; explore ethical dilemmas |

| Maling | 35 | Swedish | Psychologist | Conscience | Fan of Westworld |

| Robert | 35 | Spanish | Actor | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Teddy | 30 | Swiss | Entrepreneur | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Theresa | 36 | Austrian | Web developer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Arion | 37 | German | IT manager | Demetra | Gender role reversal; fan of LARP; try an international experience |

| Despoina | 33 | Italian | Teacher | Demetra | Gender role reversal |

| Hecate | 32 | Swiss | Biomedical scientist | Demetra | Fan of spy fiction; fan of LARP |

| Iacchus | 36 | Italian | Psychologist | Demetra | Fan of LARP; extended romantic date with partner |

| Kora | 35 | Belgian | Communications officer | Demetra | Gender role reversal; setting of the LARP |

| Catelyn | 27 | Italian | Waiter | Dracarys 2016; 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones (2016); staff member at Terre Spezzate (2019) |

| Jon | 33 | American | Retail manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

| Missandei | 28 | Italian | Childcare worker | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; medieval times frame of the LARP |

| Olenna | 45 | Italian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Sansa | 47 | Irish | Translator | Dracarys 2019 | Unfinished storylines from Dracarys 2016 |

| Shae | 31 | Russian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Varys | 34 | Italian | IT manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Nationality . | Occupation . | Field site . | Motivation for participating . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arya | 30 | Italian | Salesperson, actor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Cersei | 30 | Italian | Teacher | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Daenerys | 29 | Russian | Magazine editor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Gilly | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Try a new experience |

| Jaime | 43 | Italian | Salesperson | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Margaery | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Melisandre | 20 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; carving her own story out of the Game of Thrones universe |

| Samwell | 28 | Italian | Architect | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; fan of LARP in general |

| Theon | 38 | Italian | Performing artist | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; designers’ reputation |

| Thoros | 43 | Italian | Financial consultant | Dracarys 2016 | Designers’ reputation; taking part in an epic, massive LARP |

| Ygritte | 47 | Italian | Clerk | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Ashley | 44 | Scottish | IT manager | Conscience | Experience objectification and dehumanization by playing a robot host |

| Caleb | 31 | Italian | Salesperson | Conscience | Fan of LARP in general; helping staff the LARP |

| Dolores | 38 | Norwegian | Game designer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; fan of immersive game experiences |

| Elsie | 33 | Norwegian | Policy advisor | Conscience | Explore what makes us human |

| Emily | 28 | Spanish | Microbiologist | Conscience | Fan of science fiction in general; fan of LARP; explore more mature themes |

| Lauren | 59 | Danish | Museum education officer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; explore ethical dilemmas |

| Maling | 35 | Swedish | Psychologist | Conscience | Fan of Westworld |

| Robert | 35 | Spanish | Actor | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Teddy | 30 | Swiss | Entrepreneur | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Theresa | 36 | Austrian | Web developer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Arion | 37 | German | IT manager | Demetra | Gender role reversal; fan of LARP; try an international experience |

| Despoina | 33 | Italian | Teacher | Demetra | Gender role reversal |

| Hecate | 32 | Swiss | Biomedical scientist | Demetra | Fan of spy fiction; fan of LARP |

| Iacchus | 36 | Italian | Psychologist | Demetra | Fan of LARP; extended romantic date with partner |

| Kora | 35 | Belgian | Communications officer | Demetra | Gender role reversal; setting of the LARP |

| Catelyn | 27 | Italian | Waiter | Dracarys 2016; 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones (2016); staff member at Terre Spezzate (2019) |

| Jon | 33 | American | Retail manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

| Missandei | 28 | Italian | Childcare worker | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; medieval times frame of the LARP |

| Olenna | 45 | Italian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Sansa | 47 | Irish | Translator | Dracarys 2019 | Unfinished storylines from Dracarys 2016 |

| Shae | 31 | Russian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Varys | 34 | Italian | IT manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Nationality . | Occupation . | Field site . | Motivation for participating . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arya | 30 | Italian | Salesperson, actor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Cersei | 30 | Italian | Teacher | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Daenerys | 29 | Russian | Magazine editor | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Gilly | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Try a new experience |

| Jaime | 43 | Italian | Salesperson | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Margaery | 21 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones |

| Melisandre | 20 | Italian | Student | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; carving her own story out of the Game of Thrones universe |

| Samwell | 28 | Italian | Architect | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; fan of LARP in general |

| Theon | 38 | Italian | Performing artist | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of Game of Thrones; designers’ reputation |

| Thoros | 43 | Italian | Financial consultant | Dracarys 2016 | Designers’ reputation; taking part in an epic, massive LARP |

| Ygritte | 47 | Italian | Clerk | Dracarys 2016 | Fan of LARP in general |

| Ashley | 44 | Scottish | IT manager | Conscience | Experience objectification and dehumanization by playing a robot host |

| Caleb | 31 | Italian | Salesperson | Conscience | Fan of LARP in general; helping staff the LARP |

| Dolores | 38 | Norwegian | Game designer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; fan of immersive game experiences |

| Elsie | 33 | Norwegian | Policy advisor | Conscience | Explore what makes us human |

| Emily | 28 | Spanish | Microbiologist | Conscience | Fan of science fiction in general; fan of LARP; explore more mature themes |

| Lauren | 59 | Danish | Museum education officer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; explore ethical dilemmas |

| Maling | 35 | Swedish | Psychologist | Conscience | Fan of Westworld |

| Robert | 35 | Spanish | Actor | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Teddy | 30 | Swiss | Entrepreneur | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Theresa | 36 | Austrian | Web developer | Conscience | Fan of Westworld; setting of the LARP |

| Arion | 37 | German | IT manager | Demetra | Gender role reversal; fan of LARP; try an international experience |

| Despoina | 33 | Italian | Teacher | Demetra | Gender role reversal |

| Hecate | 32 | Swiss | Biomedical scientist | Demetra | Fan of spy fiction; fan of LARP |

| Iacchus | 36 | Italian | Psychologist | Demetra | Fan of LARP; extended romantic date with partner |

| Kora | 35 | Belgian | Communications officer | Demetra | Gender role reversal; setting of the LARP |

| Catelyn | 27 | Italian | Waiter | Dracarys 2016; 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones (2016); staff member at Terre Spezzate (2019) |

| Jon | 33 | American | Retail manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

| Missandei | 28 | Italian | Childcare worker | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; medieval times frame of the LARP |

| Olenna | 45 | Italian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Sansa | 47 | Irish | Translator | Dracarys 2019 | Unfinished storylines from Dracarys 2016 |

| Shae | 31 | Russian | Nurse | Dracarys 2019 | Try a new experience |

| Varys | 34 | Italian | IT manager | Dracarys 2019 | Fan of Game of Thrones; try a new experience |

Netnography

The first author joined the Dracarys 2016, Conscience, and Demetra Facebook groups as a participant-researcher 11, six, and two months before their respective staging. These socially mediated communities eased coordination among participants, character relationships, and a shared interpretation of the governing frames. We manually scraped all records. Netnography was particularly useful in illuminating the post-LARP phase. Participants often continue to interact on social media after a LARP ends, reliving and sharing stories (van Laer et al. 2019); reevaluating the governing frames; and organizing out-of-character social gatherings. Given this continued existence and the mediated nature of the interaction, netnography was central to refining and finalizing our research program (Kozinets 2019), particularly the focus on the challenging return to ordinary life, and the tension between realms.

Data Analysis

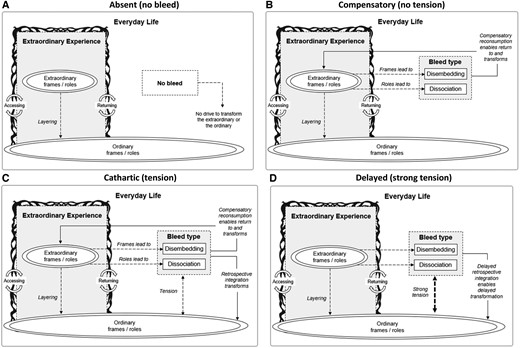

Our analytical strategy involved four stages of (re)interpretation across units of analysis, with the goal of distilling an overarching theory. First, we used open coding to isolate the composite concepts, grounding the observed phenomenon—using in-vivo labels whenever possible (e.g., “cannot stop thinking about what happened,” “watching the story again”)—and calibrating our research program toward the emergent codes. For example, we noted the impressive accounts of difficult returns to ordinary life and thus focused the research program to home in on this challenge. Second, we used axial coding to find the relationships between first-order concepts and aggregate them to second-order themes, including “disembedding,” “dissociation,” “frames under tension,” “roles under tension,” “extraordinary transformation,” and “ordinary transformation.” Third, we heavily iterated between the second-order themes and existing literature on extraordinary experience and frame analysis. Using selective coding, we derived three aggregate categories: (1) bleed types, (2) bleed intensifiers, and (3) transformation. Fourth, we returned to our data and using our coding from stage 3, developed detailed summaries of each informant’s bleed trajectory (for a similar procedure, see Mannucci et al. 2021). We charted these trajectories to better understand how individual consumers differ in their return and to formalize a recursive transformative process (Giesler and Thompson 2016).

FINDINGS

Bleed Types: The Traces Left by the Extraordinary

Uprooted from the extraordinary frames and disrobed of their roles, LARPers leave the experience but do not always make a clean break. The emic term “bleed” captures the challenging transition from extraordinary to ordinary life. Bleed stands for the “trace” left by the experience, “if only by its absence” (Goulding and Saren 2016, 221). Our informants figuratively use the definition of bleed as a liquid substance, such as dye seeping into an adjacent area: “If you have different colors and they bleed into each other, so this is your LARP character or LARP experience bleeding into your life and back” (Arion 2019, interview). We find two distinct forms of bleed: disembedding, characterized by removed access to extraordinary frames, and dissociation, characterized by consumers’ separation from extraordinary roles.

Disembedding Bleed

Disembedding describes consumers’ separation from the frames that prescribe how to navigate the extraordinary space and time. As Goffman (1974) mentions, extraordinary frames offer beliefs, norms, and values that engage consumers in the experience. Just as the vampire myth when layered onto ordinary pubs, changes them into dark, cavernous spaces (Goulding and Saren 2016), so too the lore of Game of Thrones when layered onto a geographic location, turns Rezzanello Castle, Italy, into the make-believe ruins of Summerhall, Westeros. These frames provide Dracarys LARPers with a “shared cultural code” (Daenerys 2016, interview) they can use to orientate themselves. As Cersei (2016, interview) puts it: “You are in a castle, the scenography is awesome, you eat, drink, and sleep in-game, so you find yourself completely detached from the real world for three days.” Such “upkeying” (Goffman 1974) of the real world has a dreamlike quality according to Sansa (2019, interview):

There is a part of you that remembers this is not real, but you are deliberately suppressing that and because everybody is doing the same if they are doing it properly it is very, very immersive, and very, very convincing, it is a bit like a collective dream.

Not surprisingly, letting go is challenging. Disembedding bleed leads consumers to share their longing for the upkeyed space and time on social media: “I just arrived home and I feel something is missing. The starred sky, the rags worn, the voice of the dragon, the ancient ruins. I just arrived home knowing I left another” (Tyrion 2016, Facebook post). However, disembedding is much more than sentimental longing for a lost world. The extraordinary frames layer normative prescriptions onto the experience which then ooze into ordinary life. As previously mentioned, Demetra reversed traditional gender roles. Afterwards, Arion (male, 2019, interview) had an instance in which frames collided:

When I went to a door and a woman was approaching the door too, and because I always did that in Demetra, I waited for the woman to open … the door, yeah? Because in Demetra it was something for the women to do, to help the weak men, yeah? And she stands there, and she was waiting for me to open the door, and I am waiting for her to open the door.

In this encounter, Arion views an ordinary situation through the lens of the bleeding extraordinary frame of Demetra. Dolores (2018, Facebook post) mentions a similar incident after having been a park guest in Conscience:

I had the weirdest (positive?) bleed experience yesterday. Ran into a distant work acquaintance coming into a hotel lobby at this festival where I am for work. When I was forced to do small talk … I just did it without a hitch, then even actively introduced myself to his handsome friend, engaged in some pretty funny – and in retrospect calmly flirty – banter with this random handsome stranger, said goodnight and “I'll catch you guys tomorrow” (even though the likelihood I'll ever see the stranger again is close to zero). Walking to the elevators I caught myself reflecting something like “I set that up pretty well for play tomorrow”. And finally understood what had happened. I still had this behaviour pattern from the larp that if you walk around as a guest in a strange town and are approached, someone is offering you play or plot, and you should engage with them from a position of curiosity and confidence.

In summary, disembedding bleed appears when the extraordinary frames escape the experience. Such instances happen to participants in extraordinary experiences other than LARP, too. The spirit of rebelliousness and frontier liberty experienced during motorcycle rallies flow into (week)daily life of weekend bikers (Schouten and McAlexander 1995). Goths return from the Whitby Goth Weekend carrying with them a trace of a welcoming world of darkness into one that is less accepting (Goulding and Saren 2016). Modern mountain men (Belk and Costa 1998) and scallop-shell adorned pilgrims (Husemann and Eckhardt 2019) experience clashing temporal logics upon returning from decelerated rendezvous and Camino.

Dissociation Bleed

Reflecting consumers’ separation from their extraordinary roles, dissociation describes the difficulty of letting go of a character. Arya (2016, interview) expresses why when Dracarys ended, she felt terrible: “When you play a character, you feel free to play it fully, when I cried, I was crying for real. When I laughed, I laughed for real. It’s a complete immersion.” Taking on extraordinary roles, LARPers become attached to the characters they “lived with another mind and another heart,” as Brienne (2016, Facebook post) refers to her character Rhialta:

In three exhausting but too short days I have told a massive, choral story and I’ve lived with another mind and another heart, as I felt this “mask” terribly mine.… Rhialta Vance, the dancer, the faceless woman burnt by unknown passions, will remain a part of me. I cannot stop thinking about what happened to Rhialta, what she did, what she could do, the stories and the magic. COULD SOMEONE BRING ME BACK TO REALITY HELP!

Dissociation thus requires consumers to empathize with the character deeply, echoing video-gaming literature finding greater readjustment difficulties when consumer and character overlap (Smahel et al. 2008). Ygritte (2016, interview), who did not suffer any dissociation, explains:

Coming back is more or less complicated depending on the complexity of the character and how much it overlaps with our everyday life, our point of fracture, let’s say, the things that struck or hurt us in the past. [My character] was monolithic, I could get nothing out of it, not as learning, not as a moment of introspection on who I am, why I act, where am I going, why I react in a specific way to situations … which is what a more nuanced character allows you to do, it allows you to think about your being human in the face of events. Here, I was a sort of tank and when I died, I just said, “Goodbye darling!” and it ended there.

As consumer identities are far from strictly delineated (Appau et al. 2020; Schouten 1991; Seregina and Schouten 2017), consumers can improve their understanding of themselves and the world in which they live through the performance of extraordinary character roles (Hamby and van Laer 2022). When dissociation occurs, it is challenging because being someone else allows for the exploration of qualities, personal traits, and self-concepts, which can then percolate into everyday life and enrich everyday identities. As Missandei (2019, interview) says, this “drag” happens more easily when upkeying (Goffman 1974) allows consumers to explore traits that may have already been there but lie dormant:

To me [dissociation] bleed is dragging what I have done in the game to the external world, not being able to detach completely… I’ll give you an example, the first character I played was very stubborn, very impulsive, she would jump at every opportunity, and I am not like that, but it helped me because then I started doing that in real life too.

Bleed and Corporeality

Our conceptualization of bleed cannot ignore the body, here considered “flesh” rejective of a mind/body dualism (Merleau-Ponty 1962; Scott et al. 2017). The body acts as the mediating boundary to understand the self in the world (Seregina 2019). It is therefore the technology, thing, or tool that consumers use to take on an extraordinary role (Seregina and Weijo 2016) and the canvas on which extraordinary frames are painted during the experience. Designers play a vital role in upkeying frames and roles by producing event spaces that ease sensory experiences for the body (Hill, Canniford, and Eckhardt 2022), facilitating the embodiment of extraordinary frames and roles in turn. For instance, participants can feel the steep staircase leading down into the sunken tower, smell the flourishing mold growth, and touch the skull of Balerion the Black Dread (see figure 1). Once embodied, extraordinary frames and roles can surface viscerally as exaggerated startle responses hours or even days after the experience, as the first author recorded in his field notes after Conscience:

We are sitting outside a bar in Malaga on a quite windy afternoon. The event ended yesterday, and we have three hours to kill before our flight. Suddenly, while we are sharing memories from the event, we hear a *bang* sound. Our right hands lash toward the side of our leg, trying to grasp a gun that, until yesterday, was faithfully resting in our holsters and now is no longer there. After three seconds, we realize that a gust of wind has knocked down a pavement sign, and we all burst out laughing. Maeve says, “I think we have a problem” (2018, field note).

Costumes, tattoos, food, and drink also support upkeying frames and roles (Goffman 1974; Head, Schau, and Thompson 2011). Thoros (2016, interview) explains: “Costumes and props are fundamental to reinforce the illusion” which is why he spent considerable time crafting and training with the flaming sword wielded by his character (see vimeo.com/309042250). Flaming swords and other fantastic objects symbolize upkeyed frames, and for Cersei (2016, interview) these symbols make for “a more immersive experience, because knowing these details helps you [recall] information like you had that information in your real life.” The costumes and props that support role enactment are not extinguished in the extraordinary however, since they are made of everyday materials. Bernard (2019, Facebook), whose character wore four golden rings, recounts how his body still craves them:

Getting rid of Isaac Rothschild is harder than I thought. I have tried to remove the rings (with success). But some hours without the rings is hard, the abstinence starts kicking in. I’m starting to touch and “jerk” where the rings were.. I need my rings..!* At least there is progress. I started off with three rings, now I’m down to two rings. Reducing more is the toughest part. Is there any rehab facility for ring addiction? Advices appreciated.

Edit: I need HIS rings..!

Charlotte comments: “Take all the time you need to remove the rings, no hurry. And take good care of yourself.” Clementine follows: “Some characters never truly leave you.” Notes from the first author’s participant observation corroborate these accounts: limited movement as a disabled person in Dracarys 2016; cold, fatigue, and hunger during the desert nights in Conscience; physical pain while fighting as a gladiator in Demetra; and diegetic dreams while sleeping during and after the LARPs are all layered onto his body.