-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rohit Varman, Hari Sreekumar, Russell W Belk, Money, Sacrificial Work, and Poor Consumers, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 49, Issue 4, December 2022, Pages 657–677, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac008

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

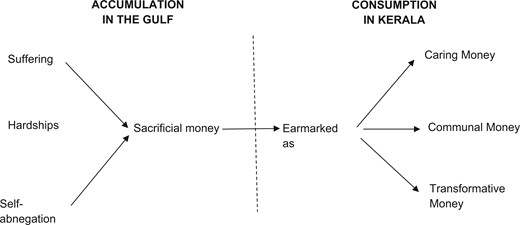

This is an ethnography among poor migrants from Kerala, India to the Middle East. This study offers insights into how the poor accumulate sacrificial money through sufferings and self-abnegation, and earmark it for consumption in Kerala. The hardships endured to earn the sacrificial money transform it into a sacred object. The phenomena of accumulation, earmarking, and meaning making of sacrificial money by the poor can be understood through the concept of sacrificial work. Sacrificial work is a spatially demarcated circuit of accumulation of money through hardships and its conflict-ridden transfer to family, community, and self for consumption. In sacrificial work, the poor erect a boundary around this money, and earmark it as caring, communal, and transformative. By delineating the various aspects of sacrificial work, this study brings to the center a behavior that has, in spite of its ubiquity, been relegated to the margins of consumer research.

Poor consumers suffer stigma (Adkins and Ozanne 2005; Crockett 2017), violence (Varman and Vijay 2018), restrictions (Hill 2002), and exclusion (Martin and Hill 2012). Moreover, poverty means that managing money becomes one of the central aspects of a poor consumer’s life (Collins et al. 2009). These conditions imply that poor consumers’ lives are qualitatively different from those of the more privileged. But consumer culture theory has not paid enough attention to the lives of the poor, especially in the Global South. Given the scale of global poverty, such an oversight is tragic. As a small step toward remedying this limited attention, we examine how poor Indians sacrifice as migrant laborers in the Arab/Persian Gulf in order to give meaning to money for improving the life situations of their families, community, and themselves.

Money almost always has extra-utilitarian meanings (Needleman 1991; Zelizer 1994/2017). Several scholars have examined the nonutilitarian, symbolic, and social dimensions of money such as its sacred meanings (Belk and Wallendorf 1990), and its ability to act as a signifier of product quality and a means of identity management (Moor 2018). Bradford (2009, 2015) points out the relational aspects of money wherein it takes on non-fungible meanings through processes of indexical and prosaic earmarking. We add to this small but significant stream of research on the nonutilitarian dimensions of money by studying poor consumers. We draw on the writings that have examined social meanings of money (Belk and Wallendorf 1990; Bradford 2015; Dodd 2014; Zelizer 1989, 2011, 1994/2017), and pay attention to how money is accumulated, transmitted, and used, to understand its sociocultural situatedness and character for the poor. We particularly focus on one such social meaning that has not been examined in consumer research—money that is invested with sacrifices. We label this special kind of money “sacrificial money.” Sacrifice is a polythetic term that encompasses a range of activities and broadly has come to mean the voluntary relinquishing of what one finds valuable in order to effect desirable transformations in one’s own or others’ lives (Eagleton 2018). Moreover, in a departure from past studies that have primarily focused on the use of money (Bradford 2015), we study both accumulation and usage to understand the different properties of sacrificial money and to develop the concept of sacrificial work. We understand sacrificial work as a spatially demarcated circuit of accumulation of money through hardships and its conflict-ridden transfer to family, community, and self for consumption.

We conducted ethnography among poor migrants who migrate to the Middle East on temporary work permits from Kerala in southern India. These migrants undergo considerable hardships while they are located in workplaces abroad and accumulate sacrificial money which is then remitted to families in Kerala. Our study is one of primarily men from South Asia, but it could have been of women from various parts of the Global South who seek to feed, educate, and improve the lives of their families by leaving them and working abroad (Singh 2017). It sounds innocent enough when it is described as global flows of people seeking opportunities in more affluent parts of the World (Appadurai 1996). But these are husbands and wives, mothers and fathers, who leave their families for years at a time in order to better provide for them.

While McCarraher (2019, 1) holds that “…capitalism evacuated sacredness from material objects and social relationships,” we find that money, sacralized by sacrifice, can be a supreme symbol and proof of sacred social relationships. In sacrificial work, the poor earmark and erect a boundary around monies, earned through hardships, that are set aside for sharing within their social networks. In doing so, they restrict and repurpose prosaic and indexical earmarking. The self-denial of prosaic earmarking and the repurposing of indexical earmarking help to sacralize this money by taking it out of ordinary consumption. These allocations are marked by a politics of conflictual redistribution as the sacrificial money is earmarked as caring, communal, and transformative monies. The sacrifice of these poor reminds us that “The first coin was not a practical means of symbolizing exchange (as the economists believe): the earliest coins were temple tokens, pilgrimage souvenirs, detachable bits of holy power” (Wilson 1998, 41). That is, certain monies are sacred (Belk and Wallendorf 1990). They are made so in the present case by the sacrifice of these poor persons. Moreover, the concept of sacrificial work helps us to deepen the understanding of the “relational work” of poor migrants or how social relations are actively shaped and negotiated by money (Zelizer 2012, 146). By delineating the various aspects of sacrificial work, we bring to the center a behavior that has, despite its ubiquity, been relegated to the margins of consumer behavior literature.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

This section provides a brief overview of the literature on money and its social meanings, highlighting how these meanings have been inadequately examined in a context marked by poverty and deprivation. We further draw on the literature on sacrifice, to help contextualize our understanding of the ways in which sacrificial behavior of our participants inflects the social meanings of money.

Money and Its Meanings

Early theorization about money viewed it as a problematic object, antithetical to community, and destructive of the social (Marx 1990; Nietzsche 2003). Simmel (1907/1978) took a more benign view of money, suggesting that while it threatens to commoditize social ties and to depersonalize human interactions, it also enables freedom, and allows escape from oppressive regimes such as slavery and enforced communitarianism. Researchers focused on traditional societies portrayed a simplistic dichotomy between precapitalist and capitalist societies, suggesting that “special monies,” used for only certain purposes, was a peculiarity of traditional peoples (Bohannan 1955; Dalton 1961; Einzig 1966; Polanyi 1957; Quiggin 1949).

Subsequent studies debunked this view, suggesting that the social basis of money remains as powerful in capitalist economic systems as it was in precapitalist societies, and arguing that a purely utilitarian reading of general-purpose or modern money overlooks how money’s cultural, political, and social significance beyond utility continues to shape human actions and social relations (Appadurai 1986; Bloch and Parry 1989; Melitz 1970; Simiand 1934). Adding further nuance to this argument, Parry (1989) suggests that, contrary to dominant notions in literature about communitarian gifting vis-à-vis atomizing market transactions, gifted money can be seen as harmful to the receiver, while money earned through commercial transactions can be viewed as helpful. Furthering this approach, Zelizer (1989) reintroduces the notion of special monies, suggesting that lottery winnings, accident compensation, windfall income, inheritances, and honoraria, are among the sources that provide such non-fungible special monies. These monies may be used for some purposes, but not for others.

More recently, offering a correction to her initial reading, Zelizer (1994/2017) moves away from the idea of special monies because it suggests that the social meaning of money is about anomalies and exceptions, and not about market money. She corrects this impression by noting that social meanings are central to market money and cannot be confined to the margins. Exploring the quality of monies does not deny money’s quantifiable and instrumental characteristics, as pointed by Marx and Simmel, but new thought moves beyond them, suggesting very different theoretical and empirical questions from those derived from a purely economic model of market money. For instance, how does money circulate within the family and how is it allocated and used? How do changes in social and power relationships between family members affect the meaning of money? Furthermore, Zelizer (2012) emphasizes relational work over relational embeddedness in her understanding of money to draw attention to relational processes that shape its use. Relational work stresses that:

For each distinct category of social relations, people erect a boundary, mark the boundary by means of names and practices, establish a set of distinctive understandings that operate within that boundary, designate certain sorts of economic transactions as appropriate for the relation, bar other transactions as inappropriate, and adopt certain media for reckoning and facilitating economic transactions within the relation (Zelizer 2012, 146).

Instead of assuming the embeddedness of money in already existing social relations, relational work pays attention to how social relations are actively shaped and negotiated by money.

Zelizer’s work has inspired some key writings on money in consumer research. For example, Belk and Wallendorf (1990) point out that money can be sacred or profane, depending on its source, and such a distinction determines the uses to which it is legitimately put. Accordingly, money can be either good (e.g., religious donations, the “nest egg”) or evil (e.g., blood money, ransom money). Moreover, Belk and Wallendorf (1990) note that sacrifices made in the accumulation of money can render it sacred. Further, in many cultures, money that is acquired through labor and hardship is valorized, and more precious than winnings, windfalls, and ill-gotten gains. For Belk and Wallendorf (1990), while money in itself is not sacred or profane, it can acquire sacred meanings as a result of processes such as acquisition through hard labor. Such a position resonates with Douglas’ (1967) observation that money becomes sacred when it is used to amend social status. While Belk and Wallendorf (1990) make the point that hard labor sacralizes money, they do not delve into how money is earmarked and the role of such earmarking in sacralization.

Drawing on Zelizer’s (2011) work on earmarking of monies, grounded in social relations and shared meaning systems, Bradford (2009, 2015) explains how earmarking transforms fungible money into a moral and social resource. She contends that prosaic earmarking sets aside funds for acquisitions of mundane or typical possessions, whereas indexical earmarking sets money aside for acquisitions of symbolic or relationally oriented possessions. Bradford (2015) further develops a typology of the consumer goals that result from a relationship between indexical and prosaic earmarking versus thriftful and splurging provisioning approaches. Here, thrift and splurge provisioning transform money into moral and social resources, respectively (Bradford 2015). As we discuss in the following section, this is also consistent with Miller’s (1998) account of the thrift and effortful sacrifices of British wives and mothers in provisioning for their families. Accordingly, the allocation of money is interactive and relational, transforming money into a singularized social and moral resource. Further, in a more recent study, Moor (2018) shows that money has semiotic potential, serving as a signifier of identity, affiliation, and collectivity. Moor (2018), however, warns that consumers’ personalization of money in digital transactions is restricted by opaque technological systems that are created by businesses. While Moor’s concerns about businesses are relevant, others have argued that digital systems of gifting money, such as WeChat Red Envelope, a Chinese mobile app for people to gift digital money, may instead foster relationships and social bonds (Chen and Gu 2018; Weng, Chen, and Chen 2020).

In summary, several scholars have highlighted the social meanings of money, its role in relational work, and its lack of perfect fungibility. Research shows that earmarking transforms money into social and moral resources. Relational work offers insights on how the meaning of money dynamically shapes, and is shaped by social relationships. While these writings help to comprehend money and its relational aspects, our focus on poor consumers whose lives are structurally and culturally bound to sacrifice opens up new insights about sacrificial money not available to prior researchers. Using the lens of sacrifice in the context of poverty helps us to understand how consumers face suffering and engage in self-abnegation to invest money with special meanings. We now elaborate on some of the key interpretations of sacrifice.

Sacrifice

Scholars have studied different aspects of sacrifice, showing that it is a polythetic, conflict-ridden practice that can manifest in diverse actions such as purchase, gifting, self-abnegation, exchange, communion, absolution, and expulsion among others (Eagleton 2018; Evans-Pritchard 1956). In consumer research, sacrifice is voluntary relinquishing of what one finds valuable for the sake of others. Such sacrifices are highlighted in many domains such as caring, shopping, gift giving, and resistance to consumerism (Epp and Velagaleti 2014; Fischer and Arnold 1990; Hamilton and Catterall 2006; Kozinets 2002; Miller 1998). For example, Thompson (1996) points out that sacrifice plays a role in the construction of care, describing how professional working mothers juggle responsibilities, compromising their professional interests to construct motherhood-centric feminine identities. Similarly, Joy (2001) shows the role of sacrifice in Chinese filial gift giving, which is characterized by love and caring, and an absence of reciprocal expectations. Further, Hamilton and Catterall (2006) find that mothers sacrifice self-gratification to send their children to school better clothed and equipped than the family can reasonably afford. Such emphasis on relinquishing something valuable for the sake of others is also central to Miller’s (1998) study of shopping in London. Miller argues that both shopping and sacrifice involve activities in which the labor of production by the woman is turned into consumption by the family. More recently, in a departure from extant research that examines sacrifices of money, time, and sentimental objects, Bradford and Boyd (2020) study organ donation, an extreme form of relinquishing. Bradford and Boyd (2020) highlight three types of sacrifices: psychic, pecuniary, and physical. These are exceptional sacrifices that require considerable deliberation on the part of consumers, who have to negotiate pressure from family members and norms that discourage organ donation.

Sacrifice is not necessarily only about a loss or suffering (Beattie 1980). We can also view it as a “flourishing of the self, not its extinction. It involves a formidable release of energy, a transformation of the human subject” (Eagleton 2018, 7). In a classic interpretation, Hubert and Mauss (1898/1964, 13, emphasis added) describe sacrifice as an “act which, through the consecration of a victim, modifies the condition of the moral person who accomplishes it or that of certain objects with which he [sic] is concerned.” Accordingly, sacrifice implies a consecration, in which the consecrated object passes from the profane into the sacred domain. A sacrifice helps to rid the sacrificer of impurity. The function of expiation thus becomes crucial to a sacrifice and makes it purposeful and infused with self-interest: we give up something in order to get something else. Turner (1968) agrees with such a reading and suggests that sacrifice has a cathartic property.

The presence of transformation and gain does not mean that sacrifice can be reduced to pure self-interest or atomized action. As Lambek (2014, 433) notes, “It is often that one gives up something for oneself in order to gain another thing for someone else.” Scholars foreground the role of social in making sacrifices meaningful and purposeful (Eagleton 2018). It is a situated practice that shapes social relations. These views move beyond an individual-centric view of sacrifice, and highlight its social dimensions. For instance, Smith (1889/1927) shows that participants in a sacrifice, through ritualistic consumption of a totem, assimilated it to themselves and became allied with it, and with each other.

Our brief review shows that scholars in consumer research tend to view sacrifice through the lens of quotidian acts of giving up, and as compromising one’s interests for the sake of others. These examinations of sacrifice are usually confined to how individuals give up personal consumption for the sake of family members. While these acts are undoubtedly important, and crucial to sustaining family ties, consumer research has not paid sufficient attention to self-interest and transformation in sacrifice. Moreover, and crucial from the perspective of this study, consumer research has under-examined the role of money in sacrifices. The role of money is particularly important for the poor because their lives are defined by its paucity (Collins et al. 2009). Based on our review, a key research question that emerges is: What is the role of sacrificial money among the poor in the reproduction of family, community relations, and self? We address this question in the subsequent sections.

METHODOLOGY

We conducted ethnography in three villages adjoining the Cherukara (pseudonym) municipality in Kerala and in labor camps in Dubai. Cherukara is located in the southern part of Kerala. The municipality is an administrative unit, with villages subsumed under it. The key reason for choosing this site for the study was the researchers’ familiarity with the area. The second author lived in one of the villages for a year to conduct ethnography. Participants belonged to three different villages; however, this distinction was administrative and was not necessarily the locale experienced by consumers. The Alappuzha district, where Cherukara is located, has one of the highest population densities in Kerala, consisting of 1,504 persons per square kilometer. We provide more information on the research context of Kerala in the web appendix.

We confined our study to return migrants who had worked in low-skilled or semiskilled jobs, such as construction workers, electricians, and domestic workers. We identified a return migrant as someone who had returned from one of the Gulf countries after working there on a work visa. The “returned” status of these migrants is often uncertain, since the migrants themselves sometimes express a wish to go back to the Gulf. However, in our experience with participants, these trips back to the Gulf rarely materialize, and the migrant usually settles down permanently in Kerala, engaging in a small business venture, or in a semi-skilled job.

The second author is a native of Cherukara, and over time had developed contacts and acquaintances in the area. Moreover, he also has a few members of his extended family living there. The presence of relatives and friends in the area facilitated entry into the setting. These local contacts helped arrange accommodations in a centrally located area in Cherukara, near participants’ homes. These contacts also helped in accessing potential participants for the study. Familiarity with the local language and customs helped in minimizing participant reactivity. We interviewed most participants in their homes, so that they could converse with us in the context of their everyday experiences. Snowballing and further referrals helped us in meeting new participants. A few of the participants actively supported us, helped us connect to new participants, and became our ethnographic guides. We used purposive sampling and interviewed participants belonging to different religions and castes, including both recent (returned less than 5 years ago) as well as older return migrants.

The interview duration ranged from one to three and a half hours. We employed McCracken’s (1988) long interview method. We used broad questions, which were followed by more specific ones depending on a participant’s responses. Some key questions were about the migrant’s occupation and consumption behavior in their current place of work, how they saved and spent money, experiences in the Gulf while dealing with fellow migrants from Kerala as well as from other parts of the world, any perceived discomfort experienced due to being an “outsider” in the Gulf or when they returned home, goods brought back home during vacations and when returning from the Gulf, expectations by relatives and extended family in Kerala, society’s and the migrant’s views of how a Gulf returnee should behave, and the migrant’s plans for the future.

We conducted interviews with 29 consumers in Cherukara and 15 consumers in Dubai. They had stayed in the Gulf for periods ranging from a year to more than ten years. Those in Cherukara had been to various Gulf states besides Dubai. In some cases, we conducted multiple interviews with a participant. Table 1 in the web appendix provides the list of key participants and basic details regarding their migration. Most of our participants were males, reflecting the gender distribution among migrants. We consciously included those female migrants who were accessible. All the interviews were in Malayalam, the primary language of Kerala.

We employed multiple methods of data collection. In addition to conducting interviews, we also observed participants, their houses, and their relationships with family members and others. We attended a meeting of the local branch of the Pravasi Malayali Association (Non-Resident Malayalis’ Association) in order to better understand popular perceptions and the political discourse surrounding the migration to the Gulf and remittances. In addition, we attended local events such as temple festivals and political gatherings to understand the setting. We took photographs and videos of participants, consumption objects, and living spaces. We also collected artifacts relevant to the phenomenon such as newspaper clippings, pamphlets, and shopping lists.

To achieve further triangulation and closure, we observed and interviewed migrant workers housed in three “labor camps” (shared accommodations of workers in many Gulf countries, usually paid for by employers) in the city of Dubai. We selected these locations because of their accessibility and convenience. We received help from friends, acquaintances, and relatives in Dubai in gaining access to labor camps. With the help of these initial contacts, we gained access to workers employed in construction and manufacturing companies in the UAE. Being in an alien land, these consumers welcomed the chance to interact with someone who was from Kerala. Notwithstanding space and time constraints, many of our participants were hospitable and went out of their way to help us. The key questions we asked pertained to the participant’s daily schedules, expenditures and consumption habits, experiences with the dominant culture, visits home and goods purchased for these visits, how they spent their limited leisure time, and any instances of discrimination and how they dealt with them. We also closely observed the migrant’s living spaces, interactions with fellow migrants, and consumption goods.

Our fieldwork resulted in a data output of 1,384 typed pages of interview transcripts and field notes. We consciously attempted to make participants comfortable by being nonthreatening in appearance, attire, and approach. We also stressed the academic nature of the study. With these safeguards, our participants were open and provided access to their lives and experiences.

In our analysis, while open, axial, and selective coding were used (Glaser and Strauss 1967), we also employed abductive methods in theorizing (Belk and Sobh 2018; Swedberg 2014). Initially, we read the transcripts line by line, and carried out open coding. This was followed by axial coding. We followed an iterative process of going back and forth between the extant literature and emergent understanding based on data analysis. Our initial interviews revealed preliminary themes of hardships, deprivations, and the importance of accumulating money. Subsequently, as we carried out more interviews and analysis, we saw that participants were employing tropes of sacrifice in their narratives. Further, participant narratives revealed the different uses to which sacrificial money was deployed. For our final readings of the data, we employed selective coding, and focused on parts of the narratives and observations where themes of sacrifice and consumption of sacrificial money were most prominent. In table 2 in the web appendix, we present a few examples of the coding schema that we used. In the next section, we present our findings.

FINDINGS

This section presents how consumers accumulate and earmark sacrificial money for consumption in Kerala. We understand this circuit of accumulation and earmarking of money as sacrificial work. Sacrificial work begins with hardships that include sufferings and self-abnegation, which result in the accumulation of money in the Gulf (figure 1). Following accumulation, the poor earmark money as caring, communal, and transformative, giving specific meanings to sacrificial monies.

Hardships and the Making of Sacrificial Money

Accumulation of sacrificial money is underpinned by hardships that include various forms of physical and emotional suffering undergone by the migrant. Migrants also undergo hardships in terms of self-abnegation in their attempts to produce sacrificial money. We elaborate on these two themes below.

Suffering

Voluntary suffering is a key element of sacrifice (Hubert and Mauss 1898/1964), which is clearly evident in participants’ narratives. Highlighting some of the features of sacrificial money, Aji, who worked as a welder in Saudi Arabia told us:

The money you get there is very different from the money you get here. I have to starve to save money. You stay there (the Gulf) for only two years. By the end of these two years, things have to work out at home. You have to be able to come back with goods. Some gold, a watch! Money has to be spent on people when you come back. Something has to be given to everyone, maybe a shirt or a mundu (wraparound garment made of cotton, worn in Kerala), something! In order to get these things over there you won’t spend even one riyal. You won’t even buy and drink, a Pepsi.

Aji’s narrative reveals the pressure on the migrant to produce sacrificial money and engage in indexical earmarking within the limited time available for the Gulf stay. Here we see the temporal and spatial bracketing of the suffering experienced by the migrant, a suffering that is endured for fixed time periods, in a geographically delimited area, to accumulate special monies. Confirming Aji’s observations, our participants kept aside much of their salaries, spending only 250 to 300 dirhams out of the 1,500 to 2,000 dirhams that they were paid monthly. Like Aji, the average migrant stays in the Gulf for limited periods, ranging from 7 to 10 years (Rajan and Zachariah 2020; Zachariah, Mathew, and Irudaya Rajan 2001). These migrants generally return home after accumulating some money, indicating that the Gulf trip is seen as a solution to the economic woes faced by the migrant (Zachariah et al. 2001). Highlighting different meanings of money, Aji recognizes that monies earned in the Gulf and Kerala are entirely incommensurate (Zelizer 1989). The Gulf money is underpinned by sufferings as physical ordeals, emotional trauma, and stigmatization that we explicate below.

Sufferings as physical ordeals play a key role in the production of sacrificial money. There is the physical difficulty of working and living in inhospitable terrain, in jobs that are often tough and even hazardous. Joseph describes the struggle he had to undergo while working at a construction site in Saudi Arabia:

A life that is so full of struggles. Sometimes one doesn’t even get good water to drink. Let me tell you about the first two years after I reached there (Saudi Arabia) …there are no trees and greenery like here (Kerala), it will be fully desert. When a house is being built, there will be heat from the top. Because of the hot wind, your face (gestures toward his face) becomes so dry. The lips, they start cracking. You tolerate all this and hang on, there won’t be good water to drink! To wet the cement, there would be water kept in large tanks. There would be a layer of dust on top of it. I have moved that dust aside, taken that water and have drunk it. Tears have come to my eyes…That much they struggle, our people, some 85 percent, that much they struggle in the Gulf and send money home.

Joseph endured extreme working conditions in the initial days after he arrived in Saudi Arabia. The inhospitable desert and the heat become even more unbearable when the Malayali migrant compares it to Kerala, with its milder weather and greenery. It is not uncommon to find workers at construction sites getting caught in the middle of the dust storms that frequently blow across the arid landscape of Dubai. Some of our participants complained that the powdery sand from these dust storms would often get into their packed lunches and make the food difficult to consume. It is difficult to even stand outdoors in such conditions, but the exigencies of work make our participants endure such difficulties.

The difficult working conditions in the Gulf are echoed by Vishwan, a labor supervisor in the Gulf. Vishwan explicitly invokes tropes of self-sacrifice to describe the sufferings:

The life in Kerala is better; you can see your father, mother, and relatives. The heat is less; the climate is good. But to live, you need money. You get everything here, but money is important to life. So even if you have to struggle a bit in the Gulf, if you get a steady income, even if you lose your life, for other people it becomes beneficial.

Vishwan clearly acknowledges the difficulties involved in living in the Gulf. However pleasant life in Kerala may be, as seen in Vishwan’s account, this life is also of poverty. In order to escape poverty, he chooses to work in the Gulf, which provides a steady source of money for his family. Here again, losing one’s life is explicitly tied to the project of making money. Further, this metaphorical loss of life is about lost time and physical labor and refers to other permanent bodily harm such as getting lifestyle diseases. Substantiating this, Hameed et al. (2013, 4) report that “diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac diseases are substantially higher in (return) migrants” as compared to nonmigrants in Kerala. Moreover, it is clear that such ordeals are undergone in order to send remittances home, as pointed out by Zachariah et al. (2001). Poor migrants undergo physical suffering to indexically earmark money. Vishwan’s reference to loss of life also strongly evokes ritualized sacrifice (Hubert and Mauss 1898/1964). Notably, the person engaged in the sacrifice here is the same as the object that undergoes trauma.

Some writings in extant consumer research highlight the role of physical suffering in sacrifice. For example, Bradford and Boyd (2020) highlight the manifestations of psychic, pecuniary, and physical sacrifice in organ donation. Arguably, organ donations involve more extreme suffering as compared to those of our participants. However, sacrifices by our participants are also bodily as many suffer long-term physiological consequences. Further, the sacrifices described by Bradford and Boyd (2020) are exceptional, unlike the sacrifices of Gulf migrants that are largely normalized as personal responsibilities within the context of family and community duties. Scholars have also theorized about consumer experiences of corporeality and physical pain (Scott, Cayla, and Cova 2017), suggesting that consumers can use pain as a means to heighten awareness of the physical body, and fashion a narrative of life satisfaction and fulfillment. Our participants however do not possess the agency of Tough Mudders (Scott et al. 2017); clearly, they are economically poor and are pushed by life circumstances to suffer pain. Their awareness of corporeality manifests itself as a predominantly negative experience, in the form of racial discrimination and lifestyle diseases acquired in the Gulf. These poor migrants do not voluntarily undergo pain; it is seen as a necessary evil and a norm to be endured for the sake of others and for oneself.

In addition to physical ordeals, our participants also face emotional trauma for multiple reasons. These poor migrants are away from family and home for extended periods. Many of our participants were especially unhappy that they missed out on their children’s childhoods. However, they view this isolation from family as a tough but necessary suffering to accumulate money. For example, Purushotaman, who has worked as a mason in Dubai for almost 30 years told us:

Here (in the Gulf), I have achieved more than I could have achieved there (in Kerala). At home (Kerala), out of 30 days you will (be able to) go to work only 15 days. Here, after expenses on food, you can save whatever money you get. But we can't live with our children and family. That is what is missing. What we feel bad about is that we have not spent time with our little children. Once in two years we go home and spend a couple of months with them. We haven't seen their childhoods. That is a sad thing.

Purushotaman was thankful for the financial gains from his prolonged Gulf stay. The Gulf stint helped him to enroll his son in a marine engineering course, and educate his daughter in a good school. However, to achieve these goals, Purushotaman pays the price of living a life that is cut off from his family and children. Studies have shown that this form of separation causes grief to the families of the migrants as well. The married women who are left behind by their husbands are referred to as “Gulf wives.” Zachariah and Irudaya Rajan (2007) estimate that 10% of the total married women in Kerala belong to this category. These women and their families left behind in Kerala experience problems such as loneliness, frustration, alcoholism, and delinquency of their children. They face many hardships and problems, since they have to struggle alone with tasks such as managing their households and finances (Gulati 1993).

Moreover, poor migrants feel stigmatized and discriminated against while in the Gulf. Stigmatization based on religion appeared to be more prevalent in Saudi Arabia, and less so in the UAE. Aji, who returned from Saudi Arabia, told us:

If they (the authorities) catch non-Muslims (who are not praying) during the sala (prayer) time, they make them pray. Then, if you are a Christian or Hindu, there is some threat. There is definitely that small threat every day. That applies to all Arab countries… If you say you are a Hindu, they will call you ‘kalb!’Kalb means ‘donkey.’

The reference to Hindus as “donkeys” indicates the prevalence of a religious prejudice, with religions other than Islam being assigned lower positions in a hierarchy. Saudi Arabia has a constitution that declares it to be an Arab Islamic State, and the rules and laws of the country closely follow Islamic sharia guidelines (http://www.the-saudi.net/saudi-arabia/saudi-constitution.htm, last accessed February 10, 2022). Such religious zealotry confines Indian migrants, especially non-Muslims, to subordinate positions. Puritanical interpretations of Islam mandate regular prayers during the day, and overzealous police officials occasionally apply these religious injunctions to non-Muslims as well. The most visible manifestation of stigmatization based on religion is work permit (called akamah) of different colors for Muslims and non-Muslims in Saudi Arabia. Muslim workers are issued green colored permits while non-Muslims carry brown permits. Green is a favored color in Islam, and hence serves to differentiate Muslims from followers of other faiths. Migrants are required to carry their akamah at all times, ensuring that the state authorities can easily identify them by religion, which also serves the purpose of keeping non-Muslims out of restricted areas such as Mecca.

The “marking” of specific categories of migrants in this manner illustrates Goffman’s (1963/1986, 1) description of stigma as a visible sign “designed to expose something unusual and bad about the moral status of the signifier.” Here, the permit serves to visibly mark out undesirable and inferior outsiders. As Meillassoux (1975, 121) observes, in addition to inculcating a sense of local superiority, the function of such stigmatization, “is to keep this over-exploited section of the proletariat, who would have every reason to rebel and turn to violence, in a state of fear.” The stigma reminds the immigrants of their inferior status and diminishes their abilities to protest oppression and exploitation. Our participants adopt attitudes of indifference and resignation as strategies to cope with stigmatization. To survive for years in unfriendly conditions and to accumulate sacrificial money successfully, migrants start by accepting the unfairness in their lives and by rationalizing it as an inevitable part of living abroad.

To summarize, our participants undergo various forms of hardships that include physical ordeals, emotional trauma, and stigmatization to accumulate sacrificial money. Our participants rationalize these hardships as the price to be paid for accumulating sacrificial money in the Gulf.

Self-Abnegation

We find self-abnegation as another constituting element of hardship in the accumulation of sacrificial money. Our participants engage in considerable self-abnegation by suppressing prosaic earmarking, and spending minimal money on individual consumption in the Gulf. There are three key features of self-abnegation. First, the migrants restrict expenditure to bare necessities such as food, basic accommodation, and minimal travel. Even for these expenses, the migrant employs various earmarking strategies such as shared cooking and housing, pooled travel in taxis, and choosing low-cost entertainment options such as visiting (but not buying at) malls on weekends. Consider Karim’s emphasis on not spending money on even personal consumption of food or water:

Those who are poor will not spend. If people think that I have a wife and children back at home, they would not even have a glass of water outside. People try to control their food expenses and send whatever money they can home.

Karim’s self-abnegation and suppression of prosaic earmarking enable him to enhance indexical earmarking to bolster his family’s living standards. Studies in Kerala show that migrant households have better amenities than nonmigrants (Zachariah et al. 2001). In order to provide such amenities to their families, migrants like Karim have to lead frugal lives in the Gulf. These men believe that it is their moral responsibility to accumulate money by making sacrifices as providers and heads of their households. Such self-abnegation acts as an essential element of sacrifice.

Another feature of self-abnegation and suppression of prosaic earmarking is the minimization of expenses on healthcare in the Gulf. In an example of self-abnegation taken to the extreme, participants claim not to seek medical help in cases of illnesses. Aji self-medicates when he perceives a minor illness:

If I get a fever, I avoid going to the hospital because I will need to spend 10 riyals there. So, if I get a fever, somehow in one week I will try to get rid of it, by working, or doing something else. In good companies there are doctors. If we approach them, they will treat us and provide medicines. In other companies, we manage (illnesses) on our own. Even if there is a fever, we act as if there is nothing wrong and go to work. The fever eventually disappears. Otherwise, I will, on my own, take a pill and cure it. One tries to save those 10 riyals.

Most of these poor migrants to the Gulf do not have any health insurance and rely on personal funds for healthcare. Aji claims that he does not visit doctors to save the “10 riyals” that the visit would entail. However, these savings and suppression of prosaic earmarking come at a cost, and as indicated by medical research on migrants in Kerala (Hameed et al. 2013), many develop several long-term ailments due to such neglect. This self-abnegation of our participants is a nuanced phenomenon. While there is self-interest involved in this accumulation process, it is clear that a large part of such accumulated sacrificial money is indexically directed toward the well-being of others. Moreover, it is crucial to remember that the migrant’s self-interest cannot be reduced to the economic self-interest posited by neoclassical theorists (Becker 1981/1991). Along the same lines as Bradford (2009), our context helps us understand how money contributes to the welfare of important others. Here, even a critical need such as healthcare is ignored to further the indexical purpose of allotting money for home consumption. Further, unlike Hamilton and Catterall (2006), we do not find a short-term perspective among participants. On the contrary, self-abnegation reveals a high ability to defer gratification and a focus on long-term, often essential goals such as housing, and providing funds for the family’s future.

Third, self-abnegation is marked by a clear focus on the hardship of working extra hours and days to minimize opportunities for personal consumption. Scholars have critiqued the dominant view of the poor as irresponsible consumers, who themselves are the cause of their poverty (Baker, Gentry, and Rittenburg 2005; Crockett 2017). Through their self-abnegation and thrift, our participants reveal a clear sense of priorities and responsibility toward family, community, and oneself. The money the poor make in the Gulf is needed for the social reproduction of labor in Kerala. This money is used to feed their families and invest in the education of children so that they can become trained to offer their labor power. Away from home, our participants do not feel the need to engage in any form of status-enhancing or self-indulgent consumption. Participants sense an absence of community and kinship networks. They cut back on almost all expenses. They do not feel the need to dress well, eat expensive food, or spend money on leisure in the Gulf. Consider the experience of Chandradas:

There (in the Gulf) we do whatever it takes to make some money. If we leave home at 6 in the morning, sometimes till 12 midnight, even 1 am, we have work. After 8 hours whatever we get is overtime payment. For money, we work overtime. Then we get paid for that too. We don’t have any homes, any relatives to visit there. So, we don’t feel like going to those places. We don’t feel like taking a day off and just lazing around. We don’t feel like being in the room.

Our participants highlighted their desire to work long hours and extra days to earn more money. Zelizer (2011), writing about remittances observes that sending money is part of being a good son, husband, or brother for men such as these. The money accumulated as a result of sacrifice is particularly precious, and migrants carefully accumulate it by working long hours. Our participants erect protective indexical earmarks around sacrificial money by avoiding personal consumption to minimize its dissipation.

In summary, poor migrants from Kerala undergo hardships in terms of suffering and self-abnegation to accumulate sacrificial money in the Gulf. Moreover, migrants engage in considerable self-abnegation during their Gulf stints and place a premium on earning sacrificial money with indexical earmarking. The migrants do not engage in abstinence as an end in itself; rather, self-abnegation is directed toward achieving the concrete and expressed goal of caring for families back home in Kerala. We provide further illustrative data for each of these tropes of hardships and the making of sacrificial money in table 3 in the web appendix.

The Earmarking and Consumption of Sacrificial Money

Given that the Gulf stay imposes substantial, often unbearable physical and emotional costs on our participants, they harbor specific attitudes toward money. They divide sacrificial money into three different categories. A large part of sacrificial money is reserved as caring money through indexical earmarking for the family, and migrants view such earmarking as a sacred duty. The second category is of the money used to meet social expectations with the indexical earmarking of communal money. The communal money is reluctantly shared with the broader community in Kerala. Finally, there is transformative money or the sacrificial money accumulated by the migrant that is indexically earmarked to overcome their subordinate status in Kerala. While we describe indexical and prosaic earmarks based on the initial distribution by migrant workers, subsequent usage of money by families, community actors, and the poor themselves may create overlaps between the two categories of earmarking. Similarly, the distribution across caring, communal, and transformative monies has categorical overlaps, as when caring money is used for a family wedding, which is also used to signal the transformation of a subordinate status. In a similar vein, family members can use caring money for communal purposes such as religious or political donations. In subsequent sections of the article, we describe how the distribution of sacrificial money affects behavior.

Caring Money

Caring for their families is a key feature of the lives of poor migrants and the most important reason for the accumulation of sacrificial money. Thompson (1996) identifies three key features of care: responsibility for enhancing the well-being of the cared for, maintenance of relationships, and anticipation of future consequences. These aspects of care are evident in the indexical earmarking of caring money by the poor as they set aside fixed amounts for their families. This earmarking constitutes a significant part of the salary, usually excluding only the money for the migrant’s living expenses in the Gulf. Sacrificial money is transferred home every month, in what can be viewed as a ritualistic process of outflow from the migrant to the family. For example, Anil told us, “I won’t have any money with me…When I get paid monthly, I immediately send the money home. The money that we send home, whether it is rupees 10000 or 20000, there is an account for that.” Anil retains around 10–20% of money with prosaic earmarking while working in the Gulf and sends the rest of the indexically earmarked money to his family in Kerala. Many of our participants have credit accounts at nearby stores, often run by Malayalis, where they procure provisions and groceries. On receipt of salary, the migrant usually settles the bill at the store, and sends home the rest of the money, retaining a small amount for personal expenses. Elaborating on the process, Joseph explained,

The exchange rate appears every day in the newspaper and TV. It is available on the internet too. So, on the day of the salary, everyone will calculate, how much will one riyal be, now it is 12 rupees 35 paise. From which bank will you get a higher (exchange) rate, so they send it to that bank. They will send the money (to Kerala).

Such money transfers play a critical role in enhancing the well-being of those cared for. As Zelizer (2005, 162) notes, “Caring relationships feature sustained and/or intense personal attention that enhances the welfare of its recipients.” Here, the money used for caring is indexically earmarked as special, and in order to suppress prosaic money, the migrants immediately transfer it to their families. Apart from the monthly electronic transfer, for ad hoc family expenses, the migrant leaves signed checkbooks at home. Vincy, a domestic worker in Dubai told us, “my husband (also a migrant) has left his checkbook at home. So, people [family] withdraw money from his account. If the requirement is urgent, he will make a money transfer.” Their younger daughter is facing financial difficulties in Kerala, and Vincy and her husband have left signed checks so that she can use the money for her expenses. As Joy (2001, 246) suggests about familial love, care, and sacrifice, these signed checks and electronic remittances create a system of asymmetrical giving of their monies by migrants to their families. The caring money helps the families sustain themselves and meet their living expenses. It is also used to pay for children’s tuition fees, purchase of land, and construction of houses. Possessing a house is seen as an important marker of stability, and providing for one’s family.

Scholars have suggested that caring for dependent family members becomes the “ultimate gift,” which helps both the giver and the recipient (the giver gains in self-esteem and benefits others) (Ruth, Otnes, and Brunel 1999). Our participants engage in acts of ultimate giving as their top priority when they provide most of their sacrificial earnings as caring money to their family members. As Tommy explained, “Even if we don’t get salary here on time, we borrow from someone and send money home. The bottom-line is, we don’t live for ourselves. We live for the people back home. Even when coming back (to the Gulf) from home, we won’t have anything of our own.” While we will see that this is an exaggeration, our participants’ actions reveal that caring is action oriented and not simply ideational. The acts they perform out of caring vary by situation and type of relationship (Noddings 2013). Further, as Noddings (2013, 17) remarks, “At bottom, all caring involves engrossment. The engrossment need not be intense nor need it be pervasive in the life of the one-caring, but it must occur.” Here, as Noddings (2013) points out, engrossment need not entail being fixated on the one being cared for. However, it does require the carer to understand the situation of the one cared for, and act in a way that benefits them. Our participants reveal this form of engrossment in their preoccupation with their family members, and their needs, in their everyday attempts at putting aside money with indexical earmarking for family needs.

Apart from ensuring the well-being of the cared for, caring money is deployed by the migrant to maintain relationships, and to plan for future contingencies and expenses (Thompson 1996). Our participants often face pressure to spend money to help the family save face, and keep up with normative expectations of family members. For example, Vincy regularly transfers money to her younger daughter, since her son-in-law is not in a financially sound position. Vincy uses her hard-earned money to engage in this caring act of protecting her daughter’s marital relationship. Further, our male participants face the financial stress of arranging the weddings of their sisters and daughters. This expense is critical to maintaining a harmonious family life. Consider the case of Tommy, for whom wedding expenses (dowry, gifts, gowns, food, festivities) for female family members constitute one of the key reasons for working in the Gulf:

We will have so many plans in mind when we come from there (Kerala). We need to clear off those debts (accumulated in Kerala). So, if you ask me if you have achieved anything, yes, I have achieved. Prior to coming here (Gulf), I did not own anything. After coming here, I have purchased 2 or 3 cents (about 1,500 square feet) of land and put up a small house (in Kerala). Then my daughter got married, and I had to come here (to the Gulf) and clear off those debts. I had to sell off my land and buy another place. By the time I could clear off those debts, the next daughter had to get married. So, these things I managed to do.

Tommy credits his stay abroad as having helped him to achieve the objective of arranging for his daughters’ wedding expenses. The cost of the weddings placed a considerable burden on Tommy, who had to return to the Gulf to repay his debts. Assuring the weddings of female family members is seen as a sacred duty of male family members in India (Osella and Osella 2000), and many migrants feel strongly committed to spending large amounts of money on these weddings in the form of dowry and wedding arrangements. For instance, Karim, a security guard in Dubai had to arrange the weddings of five of his six sisters, a considerable expense which he managed to meet by staying in the Gulf for 10 years. The combined expenses of arranging his sisters’ weddings depleted most of the sacrificial money he had accumulated.

In addition to the attempt to maintain relationships and satisfy family norms, Tommy’s narrative reveals caring as planning for future expenses (“we have so many plans in mind”), as suggested by Thompson (1996). Such anticipation of future expenses is also shown in Aji’s concerns about his two daughters, when he is aggrieved that potential bridegrooms or their families demanded “one kilogram or even two kilograms” of gold. Aji further told us, “if we need a (good) groom, we have to gift this gold,” indicating that providing large dowries is an important way in which families ensure a woman’s wedding with a man of good social standing (Sood 2021). Moreover, in many weddings, the display of bridal adornments in the form of gold jewelry also serves as a means of status signaling by the bride’s family (Kodoth 2008). Ironically, despite its relatively progressive social indicators and left-leaning politics, a recent study showed Kerala as the Indian state with the highest levels of dowry inflation (Nair 2021).

In expending caring money, the migrant both furthers and has to suffer the consequences of patriarchal institutions such as dowry. The sacrifices that go into caring money also reinforce the local relations of patriarchy with men as protectors and providers of dowry for women, and also limit the agency of women (Devika 2009; Osella and Osella 2000). For instance, it is often difficult for the wives and children of migrants to live in Kerala without the physical presence of male extended family members. When Shantamma goes away on her Gulf stints, she has to leave her daughter-in-law at her parental home. It is uncommon to find women, even older women living alone in Cherukara. Thus, caring money reinforces relations of domination and dependence. As Meillassoux (1975, 75) insightfully notes, “men thus are led to protect and then to dominate women … women are forced into dependent relations which leads on to their time-honored submission.” Transferred from the Gulf as a site of production of labor, caring money translates into means of social reproduction of families and labor in Kerala. Thus, sacrificial money that gets indexically earmarked and spent as caring money has a clear relational property in it (Dodd 2014; Zelizer 1994/2017). Here, as Hubert and Mauss (1898/1964) suggest, sacrifice unleashes powerful forces, in our case, it provides migrants with power in the form of importance within the family by acquiring the ability to financially provide for its members.

To summarize, poor migrants use sacrificial money as caring monies for their families. These indexically earmarked caring monies are employed to ensure the well-being of family members, maintain relationships, especially relationships acquired through marriage, and plan for future expenses such as college education and wedding dowries. Caring money helps participant families to escape poverty and material deprivation, albeit reinforcing relations of domination and dependence within families.

Communal Money

While earmarking funds for caring money, the migrant has to indexically set aside part of the accumulated sacrificial money for communal objectives. However, unlike in the case of caring money, the indexical earmarking of communal money is an ambivalent activity, often tinged with resentment. We broadly describe two types of outflows of communal money. First, the migrant must engage in normatively expected contributions, such as donating to local Hindu temples, and gifting for weddings and rituals. Although these contributions are expected from all community members, expectations from Gulf migrants are higher. Second, the migrant feels pressured to contribute to ad hoc requests for financial assistance from other community members, often acquaintances or distant relatives. We describe these two forms of indexical earmarking of communal money below.

Gulf migrants generally live in small communities with certain expectations of them to share their wealth (Osella and Osella 2000). One such expectation is from the local Hindu temples in Kerala that usually have committees comprised of interested members, that are in charge of organizing celebrations and events. These celebrations that are funded by donations help to maintain the local social ties (Fernandez, Veer, and Lastovicka 2011). Political parties in Kerala also have similar committees and local office bearers. Committee members and volunteers pressure households to donate, and refusal to donate leads to a strained relationship with the committee, and by extension the temple or political party. Most consumers prefer to avoid this outcome. Moreover, living in a village community means getting unavoidable invitations to rituals and celebrations that involve relatives, acquaintances, neighbors, and friends. Attending these events involves expenses in the form of travel and gifts, which usually amount to at least 1,000 rupees for each such event. For someone with limited resources, this becomes a significant financial strain. Shantamma claimed to have spent 20,000 rupees, a fairly large sum for these poor consumers, on such occasions and gatherings in just one month. Shantamma further told us,

If a person who lives here (in Kerala) pays 100 rupees, we (migrants) will have to shell out at least 250 rupees. That is the most significant expense here. Money on donations. Similarly, for the temple festivals, for anything, you have to contribute more. They tell me directly, that they want so much money. I spend very little on food and related expenses. These contributions, those are the major expenses. Even people I don’t know at all might invite me to a wedding. Last month I incurred close to twenty thousand rupees on contributing to weddings. Just in this locality!

As Shantamma reveals, there are numerous socially sanctioned expectations of monetary contributions from poor migrants. Such expectations add up to considerable outflows of money, depleting the migrant’s hard-earned sacrificial money. As Bloch and Parry (1989) suggest, money is not necessarily atomizing and antagonistic to community; rather, it serves as a vehicle for expressing other-directed behavior, albeit undergirded by resentment. Here migrant behavior has parallels with that of peasant communities who believe that good things are in limited supply (Foster 1965). Akin to the societal mechanisms in these communities, our participants experience social pressure to share their wealth with the community. The migrant is often torn between the need to limit the outflow of precious sacrificial money, and the need to keep up good relations with the community. A caveat to this is that, as pointed out by Kennedy (1966), peasant societies need not be closed systems. The same holds true for village communities in Kerala; as suggested by Kennedy (1966), these are very much part of the larger culture of Kerala, and even India as a whole. It is likely that, rather than just harboring a notion of limited good, migrant gifting of goods to the community is also in line with Foster’s (1972) characterization of the use of sops for envy reduction and avoidance.

Apart from normative pressures to donate their sacrificial wealth, migrants also face ad hoc requests for financial help from community members. Aji describes the plight of the return migrant, in this somewhat exaggerated narrative:

I don’t know what the secret behind it is, but if someone goes to the Gulf and comes back, even a beggar will be able to recognize him from a distance (laughing). I don’t know what the trick is, maybe it is written on my face (smiling). Most of the time, after coming home from the Gulf, I move around in a lungi (inexpensive casual use garment). Even then, if someone asks me for something (money) and I don’t give it, the reaction is, “Why did this man go to the Gulf?”

It is easy to recognize a Gulf migrant because they are not seen in the area for long periods. Aji’s narrative has to be understood in the context of a life of impoverishment and self-abnegation in the Gulf. Despite his somewhat precarious financial situation, the community expects him to lend money to those in need.

Similarly, Shantamma finds that even distant relatives approach her for financial help. We observed one such relative of Shantamma pressuring her to lend him some funds to start a business venture.

This man wants to buy a footwear shop and a bakery at (a nearby place) … . He is a relative of ours. It will cost 200,000 rupees. He wants to borrow some money. He sees me wearing this gold now (points to the jewelry on her hands and neck—a few gold bangles and a thin gold necklace). So, he was asking for that. He wants 60,000 rupees right now.

Shantamma is middle aged and after years of financial struggle as a domestic worker had started a successful restaurant in Bahrain, and had later decided to return home. She is considered locally to be a moderately successful Gulf migrant. This leads her relatives to approach her for funds. Apart from financial contributions, community members often ask the migrant explicitly for specific foreign-made items. Shantamma’s relatives and friends had requested that she bring home back-up flashlights (popular in India because of frequent power disruptions). Even when these requests are not made explicitly, there are expectations that the migrant should bring back sought-after objects. Not meeting such expectations leads to resentment, and occasional contempt from the community. In an attempt to avoid these tiresome obligations, Shantamma even expressed her wish to go back to the anonymity of the Gulf, where she does not have to deal with community expectations. As Zelizer (2011, 350) observes, “those who fail to meet their obligations first feel sanctions and the exclusion.” A refusal to part with one’s wealth is greeted with contempt (“Why did this man go to the Gulf?”). Many in the community perceive Gulf migrants as those who have accumulated more wealth than the average resident, and thus expect them to share such wealth. Moreover, those who expect the sharing of wealth can believe that money is earned more easily in a foreign location, whereas the migrant knows that the reality is otherwise (Cabraal and Singh 2013).

Our participants feel considerable resentment because they see excessive conversion of their sacrificial money into communal money. The resentment felt by our participants adds nuance to Simmel’s (1907/1978) notion of money as a means of escape from burdensome aspects of community. The expectation placed on communal money, far from allowing such escape, further enmeshes the migrant in communitarian obligations, leading to the migrant feeling trapped. As another participant Joseph aptly put it, the money he earned in the Gulf was like ennayil chutta appam (pancakes fried in oil), comparing it to a tasty and rare delicacy made in Kerala. Such sacrificial money was precious, highly desirable, and limited. When forced to give to the community, indexical earmarking of communal money becomes a source of resentment for the poor. An important caveat here is that these resource-constrained migrants often depend on acquaintances, distant relatives, and friends to obtain jobs in the Gulf, and to take care of the needs of their families that get left behind. For example, Rajmohan and Shantamma obtained jobs in the Gulf because of useful tips and contacts that local well-wishers passed on (Kurien 2002; Osella and Osella 2000). Therefore, it is understandable that these well-wishers and others in the community expect gratitude in the form of communal money from the migrant. Given the tangible help rendered to the migrant by the community, such resentment and refusal to part with the obligatory transfer of money to the community can lead to the migrant being viewed as an opportunist or kallan (Osella and Osella 2000).

Summing up, communal money gets indexically earmarked through normative expectations from the community and ad hoc requests. Our participants are acutely conscious of the preciousness of their sacrificial money, and therefore perceive the continual demands placed on it by the community as exploitative. Thus, the migrant earmarks a part of sacrificial money as communal money for spending on the community, albeit reluctantly.

Transformative Money

Eagleton (2018) suggests that a compelling aspect of sacrifice concerns the flourishing of self. Sacrifice is expected to empower and transform the self. As a third part of the distribution, our participants deploy sacrificial money as transformative money to help them transcend their subordinate status. Unlike caring money that is essential for everyday maintenance of families, and communal money, which becomes an obligatory form of transfer, transformative money is the most discretionary. A large part of transformative money is visible, often conspicuously so, and is indexically earmarked as belonging to the migrant. Unlike a donation to a temple, which by and large goes unnoticed, an ostentatious house stands out, and serves as a concrete symbol of the migrant’s success. Moreover, the status of the migrant prior to migration has to be understood in order to situate their poverty, subordination, and the transformative property of sacrificial money. The aspiring Gulf migrant is typically young, unemployed, in many cases lower caste, and often bears financial debt. In the capitalist milieu in which our participants are situated, an inability to consume results in feelings of inadequacy and stigmatization (Hamilton and Catterall 2006; Üstüner and Holt 2007). The migrant seeks to transcend such an underclass/caste status through sacrifice (Sreekumar and Varman 2019). Migration is seen as the route to accumulating transformative money, escaping from unemployment and poverty, and achieving upward social mobility. Migration transforms the unemployed youth into the Gulfukaran, or the return migrant, who is often seen as embodying material prosperity.

Apart from getting houses built, migrants flaunt their success by arranging weddings with appropriate lavishness, and displaying accouterments of modern lifestyles, including computers, TVs, motorbikes, cars, gold jewelry, and stylish clothing for self and family members. This personal consumption can be considered a form of self-gifting (Mick and Demoss 1990) and compensatory consumption for the hardships endured (Koles, Wells, and Tadajewski 2018). Miller (1998) also observes compensatory self-gifts, finding that female shoppers in London often buy themselves and accompanying children small treats like chocolates that are secretly consumed on the shopping trip so the rest of the family is unaware of them, while the shopper uses her thrift as a justification for such self-gifting. In Kerala, by contrast, returning migrants spend indexically earmarked transformative monies on visible luxuries that are able to amend their status deficiencies (Zachariah et al. 2001). Outlining this feature Sunil, who worked in the UAE, told us:

If you are a donkey there, you become a horse here … . Let me tell you, over there (Gulf) this person will not be using good clothes, good perfume, or skin cream. Only when he comes here (Kerala), he will use it. The stuff that he won’t even dream of there, he will buy when he goes shopping, and come back here and use it when he is here for two months.

Sunil disparagingly says that the migrant, who is a “donkey there” (in the Gulf), becomes a “horse” when at home. The migrant uses consumption as a vehicle to escape from their stigmatized identity, and assume a more successful, happier persona in the home culture. As Douglas (1967) observes, money that is used for amending status is sacred. Migrants’ profligate spending at home points to the potentially cathartic release that certain forms of consumption can provide (Kozinets 2002). Our participants use the Malayalam word adichupoli (literally meaning to break up, or destroy), to refer to this form of extravagant consumption, indicating the parallels that this kind of spending has with the potlatches described by Mauss (1950/2000). While their conspicuous consumption results in the destruction of financial resources, migrants derive cathartic release and enjoyment from such consumption. The profligate spending of migrants also reminds us of Bataille’s (1989) observation that ostentatious squander not only served as a means to channel excess resources, but also served to bolster social status and improve one’s rank in society. Our participants’ conspicuous consumption closely resembles this latter form of consumption, that is, improving standing through a potlatch-like expenditure. In doing so, the migrant diminishes hard-acquired sacrificial monies, and diverts them to a project of self-transformation.

Such conspicuous consumption is enacted in a theatrical space, with the audience comprised of the migrant’s kin, friends, and local acquaintances. The sacrificial money accumulated in the Gulf helps maintain a “front” (Goffman 1959) in Kerala. Consider Sreejith who prior to migration was considered to be an immature, unemployed youth. People treated him with contempt since he lacked a productive occupation. However, after returning from the Gulf, Sreejith has set up a large retail store in Cherukara. He plans to acquire a car, and other consumer durables. The Gulf stint also helped him to get married. Sreejith is now well-respected by his relatives, and even those who earlier dismissed him as a failure now consider him to be a productive member of the community because of his visible material prosperity.

To effectively engage in self-transformation, the migrant has to indexically earmark and expend sacrificial money in visible ways. These include wearing expensive clothes and items of personal consumption, and engaging in other visible forms of consumption such as ostentatious housing. As one of our participants Sarish pointed out, “even if you have not eaten, you have to dress up. If you have not eaten, other people will not know that. But if you don’t dress well, people can see it.” Thus, we see a continued suppression of prosaic earmarking and inflation of indexical earmarking in the lives of the poor. In addition to self-transformation, such visible consumption also serves the pragmatic purpose of enabling better matrimonial alliances and receiving higher amounts of dowry and other monetary benefits associated with weddings in Kerala. For example, Sarish himself spent a large amount of money on refurnishing his house for the explicit purpose of getting married into a family of good financial standing (see also our earlier discussion on dowry in caring money).

The spending of the Gulfukaran can also signify a desire to transcend lower caste status. As Osella and Osella (1999) observe, lower Hindu castes in Kerala, such as the Ezhavas, use migration to transcend their lower caste status and achieve upward social mobility. Consider Jayan who worked as a foreman in the UAE, commenting on the display of wealth by low caste migrants who come home on vacation:

Let me tell you something, even sweepers (usually outcaste Dalits) will come back with 20,000 or 25,000 rupees in hand. They have to come back that way. So, people will see him [return migrant] when he lands and say, oh, this person looks good. So, when they ask him how things were over there, he will say, it was initially a bit difficult but later on there were no problems. But this man would have struggled there. He will take his friends, go to a restaurant or bar, and treat them.

Money becomes a vital resource to overcome generations of caste-based subordination (Vikas, Varman, and Belk 2015). Transformative money acquired through migration can enable one to transcend lower caste status, and buy one’s way into middle or upper caste dominated settings. Strategically deployed, such transformative money can on occasion even serve pragmatic purposes, such as helping the migrant’s business venture. Rajan, for example, uses his car whenever he visits prospective clients to signal to them that he is a reliable businessman. More commonly, transformative money is a signaling mechanism to the community as a whole, that the migrant is now a puthan panakkaran (nouveau riche). The migrant uses the middle-class members of the local community, rather than their specific caste, as references for status consumption. In line with these class-based norms, migrants attempt to self-transform in ways that are beyond caste markers, by deploying commonly accepted status markers such as jewelry and consumer durables (see Osella and Osella 1999). Here, as Simmel (1907/1978) observes, money allows subordinate groups to gain freedom from past ties, and be part of middle-class groups.

However, the migrant’s project of attempted self-transformation does not always succeed. While some poor can acquire transformative money and successfully challenge their earlier subordination, many are unable to do so. We came across some migrants who moved to the Gulf but could not accumulate sufficient money there. Consider the case of Joy, who had worked as a laborer in the Gulf. Joy lives in a small, sparsely furnished house, with a roof made of metal sheets. The house is not plastered or painted on the outside. By local standards in Cherukara, the house is very small and unfinished. Joy was hesitant and somewhat uncomfortable interacting with us and talking about his Gulf stint. He and his family have joined a local Christian order, which believes in austerity and frugality. Joy uses this particular form of religious belief to justify his limited consumption. Moreover, Joy does not have comfortable relationships with his siblings who live near his house. He was reluctant to even introduce us to his elder brother, who is a successful Gulf migrant. His bitterness and regret at his poverty and failure in the Gulf is evident, when he told us, “Because of the Gulf trip, I got no benefit at all. No benefit at all! I don’t even have 5 naya paisa (a naya paisa is one hundredth of an Indian Rupee) to call my deposit.” Joy’s behavior, house, and relationships with the community mirror his failure.

We observed similar behaviors in the cases of other unsuccessful migrants such as Titus and Soman. In our time in Cherukara, we never observed anyone talking to Titus or spending time with him. Titus asked us not to visit his home because his “condition was not alright.” Soman lived a materially better, less deprived life, thanks to his son and daughter, who were helpful to him. However, accepting his children’s help made him uncomfortable, and he voiced anxiety over his future. He also said that he had lost the goodwill of some of his relatives because of his Gulf failure and his inability to share wealth with them. Migrants experience failure for two reasons. In some cases, migrants such as Titus, in their desperation to accumulate money, try to visit the Gulf on short-term visas, and find employment during these visits. While on these visits, migrants can make money on odd jobs (which is against the rules). However, in the case of Titus, and another participant, Radhakrishnan, these sojourns did not result in long-term employment, and the migrant consequently experienced failure. On the other hand, participants such as Soman experienced failure due to reasons beyond their control, such as the shutting down of the firms employing them. Such failed migration parallels the phenomenon of the pavam, described by Osella and Osella (2000) as an innocent do-gooder migrant who ends up becoming an economic failure. When the Gulf migrant experiences such failure for reasons beyond their control, their predicament becomes similar to the “shattered identity projects” described by Üstüner and Holt (2007, 51). Here, the migrant’s aspirations to transform themselves get thwarted, resulting in a feeling of failure. The luckier of our participants such as Soman can fall back on their families, but many of these “failed” migrants, such as Titus and Joy have to bear the brunt of their inabilities to accumulate money in the Gulf.

To summarize, consumers indexically earmark sacrificial money in three different ways. First, they set aside a substantial part of sacrificial money to care for family members, who experience a better lifestyle through such money. Second, with some reluctance and resentment, they earmark money for spending on community. Finally, consumers use sacrificial money for transformation, wherein migrants engage in various forms of consumption, many of which are conspicuous, and seek to overcome their erstwhile subordinate status (see table 3 in the web appendix for more illustrative data).

DISCUSSION