-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Soo Yun Shin, Ezgi Ulusoy, Kelsey Earle, Gary Bente, Brandon Van Der Heide, The effects of self-viewing in video chat during interpersonal work conversations, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 28, Issue 1, January 2023, zmac028, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac028

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

With the growing use of video chat in daily life, it is critical to understand how visual communication channels affect interpersonal relationships. A potentially important feature that distinguishes video chats from face-to-face interactions is the communicators’ ability to see themselves during the interaction. Our purpose was to determine the effects of self-viewing on the process and outcome of a workplace confrontation. A dyadic experiment with two (self-viewing vs. no self-viewing) conditions was conducted using multi-instruments (self-report, physiological arousal, eye-tracking). Results showed that self-viewing reduced self-evaluation, which subsequently reduced solution satisfaction. Self-viewing also impaired one’s ability to assess their partner’s attitude and lowered partner evaluation. Although self-viewing decreased negative emotional expressions, the effect on conversation tone varied depending on the role an individual played. The overall negative impacts of self-viewing ability have significant implications for the appropriate implementation of a computer-mediated channel for enhancing one’s experience when having a difficult conversation.

Lay Summary

We now use video chat such as Zoom and Facetime to maintain our relationships in private life as well as in the workplace. The current study investigated the effects of a special feature of a video chat, which is viewing one's own face and behaviors in real-time during a conversation, on people’s workplace confrontation experience. We conducted an experiment where two people who played either a role of a boss or an employee at a workplace had a conversation to resolve their workplace issue via a video chat either with or without a self-viewing window. Results showed that people who had a self-viewing window in a video chat more negatively evaluated their own performance, which also led to more negative conversation result satisfaction. In addition, they were less likely to accurately assess their partner’s liking toward them and evaluated their partner’s ability more negatively. Lastly, when self-viewing, employees changed their conversation tone to be more positive whereas bosses’ conversation tone remained the same. Overall, this study provides evidence of the negative effects of self-viewing in a video chat, suggesting turning the self-view option off to optimize the usage of a video chat when people expect to have a difficult conversation.

Many aspects of human social life have been enmeshed with computer-mediated channels in recent decades. In particular, video chats have become a widely used communication channel with technological advancements that provide a similar number of nonverbal and verbal cues to face-to-face conversations. People now frequently use video chat channels for various interpersonal purposes and to collaborate with other people (Alcántara, 2020), even for situations when individuals used to expect or prefer in-person conversations, such as settling issues among colleagues (Markman, 2019).

Albeit being heralded as the alternative to face-to-face, video chats differ from face-to-face talks in significant ways. One of the most visible contrasts between video chat and face-to-face discussion is the presence of a self-viewing screen in video chat. In a typical face-to-face conversation, people cannot see their facial expressions, gestures, or mannerisms. However, in a video chat, the ability to monitor one’s own conversation behavior is provided by default. Furthermore, the opportunity for self-reflection does not appear to go unnoticed. Not only do many video chat users testify that they cannot stop staring at themselves (O’Gieblyn, 2021), previous research on self-related stimuli such as self-name and self-face photo suggests that people automatically pay more attention to self-related stimuli than other-related stimuli (Alexopoulos et al., 2012; Tacikowski & Nowicka, 2010).

Indeed, scholarly debate on the potential effects of self-viewing in a video chat, such as increased appearance concern, is growing (Pfund et al., 2020; Pikoos et al., 2021). However, there is a scarcity of experimental evidence testing the causal effect of self-viewing in a conversation. A few exceptions provide experimental evidence of self-viewing effects, such as increased use of socially focused words in a getting-to-know conversation (Miller et al., 2017) and decreased team performance and satisfaction in a virtual group collaboration (Hassell & Cotton, 2017). However, it is yet unclear how self-viewing in a video chat will affect interpersonal disputes when two people have different aims and perceptions of a situation. The ability to view oneself may be even more impactful in such a situation considering that to handle a difficult conversation in a productive, peaceful manner, one would need the ability to accurately assess the self’s and others’ states and attitudes and adjust their behaviors accordingly. For example, one may calm down when the self looks too upset in the chat window; or, one may change the conversation tone to be more positive when the partner seems to dislike the self, and so forth. In fact, the capabilities to assess and accommodate more appropriately are deemed important for productive conflict resolution in the existing literature (Bates & Samp, 2011; Kilpatrick et al., 2002). Given the rapid rise in the use of video chat for relationship maintenance (Wen, 2020), which is often accompanied by the task of handling conflicting issues (Braiker & Kelley, 1979), this knowledge gap regarding the potential impacts of the self-viewing feature in video chat on the experience of having a difficult conversation requires more attention.

Hence, the current study attempted to fill a gap in the literature by conducting a lab-based experiment that investigated the influence of self-viewing in a video chat when having a difficult workplace conversation. Original hypotheses and research questions regarding the diagnostic ability about the self and the partner, self-evaluation, partner evaluation, solution satisfaction, and conversation behaviors were developed based on self-perception theory (Bem, 1972) and objective self-awareness theory (Duval & Wicklund, 1972). Each prediction is discussed in greater depth below, along with relevant literature.

The effects of self-viewing in video chat

Diagnostic ability for self and partner

According to the self-perception theory (Bem, 1972), people tend to infer their internal attitudes and beliefs from their overt actions. With the unprecedented amount of observability of one’s own communication behaviors offered by computer-mediated communication (CMC), researchers have used self-perception theory to study how such observation affects one’s impression and attitudes about themselves and others. For example, Gonzales and Hancock (2008) showed that people who wrote about themselves online internalized their self-descriptions more compared to those who wrote about themselves in a private text file. Public online statements were viewed as an act of public commitment to the person’s identity. Therefore, people were motivated to see themselves more in line with their online descriptions. In an online chat study (Walther et al., 2018), people who were able to see both their own as well as their partner’s reciprocated self-disclosure reported liking their partner more than those who were not able to see the traces of their self-disclosure. Given that the act of self-disclosure is viewed as an attempt for more intimacy, people were influenced by looking at their own self-disclosure in determining their attitudes toward a conversation partner.

In a video chat, the self-view screen can also provide plenty of opportunities for a user to observe their own communication behaviors. It can give both verbal and nonverbal clues regarding a person’s communication state in real time, such as their facial expressions and gestures, and the words and sentences they use. Given that people tend to pay more attention to their own faces than the faces of others (Tacikowski & Nowicka, 2010), even a small self-view window in a video chat is likely to cause people to focus more on the self-view window on the computer screen. The ability to diagnose one's own state more effectively is expected to improve with such increased attention to and ample cues concerning self-viewing behaviors.

As such, individuals who have the ability to self-monitor during communication likely have different assessments of themselves and of their communication partners when compared to those who cannot self-monitor. Then, how do people assess their emotions and arousal state, particularly when they can self-monitor during their communication? Arousal levels rise when people are involved in interpersonal confrontations (Levenson et al., 1994). When people expect a conflict situation, their brain sends out signals to “fight” or “flee,” which are accompanied by physiological arousal such as a quicker heart rate (Gottman & Levenson, 1988). Knowing one’s arousal level during a conversation is important since it can either drive one to calm down for better conversation outcome or cause people to infer their opinions toward the issue and partner based on their arousal level. Thus, we investigated with H1 whether self-diagnostic ability for arousal, which is one’s ability to accurately assess their own physiological arousal level, would differ based on the presence of a self-view screen during a video chat.

H1. Having a self-view leads to a higher self-diagnostic ability for arousal than not having a self-view.

Although self-viewing may raise awareness of one’s arousal level, the self-view screen may also serve as a distraction from reading the emotional state of the partner. According to previous studies on interpersonal disputes, the capacity to effectively analyze a partner’s feelings is beneficial to finding resolutions (Bates & Samp, 2011; Gottman et al., 1977). Accurate assessments of another’s feelings can encourage an individual to modify their actions so that their difficult interpersonal conversation can reach a resolution more quickly (Kilpatrick et al., 2002). This process, however, can be hindered by the presence of a self-view screen due to the following reason.

According to research on human cognition, attention is a limited resource. The amount of attention given to a particular piece of information can influence how well it is encoded, retained, and utilized later (Lang, 2006). Given the instinctive focus given to one’s own face (Tacikowski & Nowicka, 2010), it is probable that self-viewing reduces the amount of attention given to the discussion partner’s face. This biased distribution of attention between self-face and partner-face, then, could reduce one’s capacity to accurately estimate the partner’s state. Relatedly, a previous study demonstrated that people who paid less attention to a target person showed a lower accuracy in assessing the person’s personality (Capozzi et al., 2020). Thus, we put forward H2 to investigate the effect of self-viewing ability on diagnostic ability in terms of assessing their partner’s actual liking toward them.

H2. Having a self-view leads to a lower diagnostic ability for partner’s liking than not having a self-view.

Self-evaluation, partner evaluation, and solution satisfaction

If the self-view screen draws one's attention away from the discussion partner and toward oneself, this divergence in attention may also alter other judgments about the self and the other. Regarding the potential impacts on self-evaluation, the objective self-awareness theory (Duval & Wicklund, 1972) suggests that self-viewing may reduce self-evaluation. According to the theory, when circumstances cause people to focus on themselves and perceive themselves as a more distinct entity, they begin to make internal comparisons between their overt actions and their ideal standards. When individuals’ current behaviors do not appear to meet their ideal standards, they are likely to experience negative affect.

Given that it is typically difficult to meet one’s ideal standards, previous studies revealed that persons who saw themselves in the mirror or listened to their own voice recordings were more self-critical than those who did not (Heine et al., 2008; Ickes et al., 1973). A meta-analysis also found that self-focus is generally related to an increase in negative affect (Mor & Winquist, 2002). According to a recent survey of video chat users, the longer people look at their own camera view, the more comparisons and self-objectification they engage in (Pfund et al., 2020). These findings corroborate the adverse effects of self-awareness. Thus, the current study posits that self-viewing in a video chat is likely to reduce the evaluation of one’s own performance in handling a difficult interpersonal issue.

H3. Having a self-view leads to lower self-evaluation than not having a self-view.

Unlike the potential consequences for self-evaluation, theories and previous research do not provide a specific direction for the impacts on partner evaluation. Rather, they provide competing predictions. On one hand, a reduction in self-evaluation can be accompanied by an increase in partner evaluation. The social comparison theory suggests that people innately compare themselves to others (Festinger, 1954). Thus, one may engage in social comparison in such a way that their partner appears more competent when contrasted to their own performance in handling tough communication, especially when people are more geared toward more critical self-evaluation. Previous research demonstrating a significant relationship between self-focus and greater social comparison (Duval et al., 1992) appears consistent with this possibility.

On the other hand, based on self-perception theory (Bem, 1972), it is possible that individuals infer their own negative views toward their partner during a dispute through self-observation. Because a difficult interpersonal conversation typically involve a higher level of physiological arousal and potentially negative messages (Zillman, 1990), individuals who can observe their anxious, stressed appearance and behaviors through a self-view screen are more likely to infer their own negative attitudes toward the partner than those who cannot observe their own negative appearance and behaviors. In other words, individuals may link the conversation's negativity to the partner and hence have a lower opinion of their partner. Due to the competing possibilities, RQ1 is offered instead of a directed hypothesis.

RQ1. How does having a self-view influence partner evaluation?

Along with self- and partner-evaluation, the influence of self-viewing can be extended to satisfaction with the outcome of the dispute dialogue. It has been observed that people have an innate urge to preserve their self-worth (Sherman & Cohen, 2006). Thus, individuals may be less happy with results that do not appear to reflect the best version of themselves. Previous research demonstrating a positive relationship between self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997) and contentment with performance, employment, and relationships (Chang & Edwards, 2015; Shih, 2006; Weiser & Weigel, 2016) indicate that how one evaluates oneself can be a critical predictor of eventual satisfaction. Hence, it is likely that when individuals believe they did not contribute sufficiently to reaching a solution, their diminished sense of self-contribution results in dissatisfaction with the resulting solution. In conjunction with H2, which anticipated that self-view in video chat has a negative effect on self-evaluation, the following mediation hypothesis is offered.

H4. Having a self-view decreases solution satisfaction via lowering self-evaluation compared to not having a self-view.

Conversation tone

Lastly, this study examined whether and how a self-view screen affects people’s communication behaviors when having a workplace dispute. Earlier research has demonstrated that people’s communication behaviors tend to change with a self-view in a casual conversation. For instance, when people can observe themselves in a getting-acquainted video chat, for example, they employ more socially oriented terms (e.g., “mate”) and fewer certainty words (Miller et al., 2017). This finding could be viewed as an attempt to conform their overt behaviors to ideal standards (Duval & Wicklund, 1972) or as a response to their increasing anxiety about their self-presentation to their conversation partner (Fenigstein, 1979).

Given that the emotional climate of a conversation has been shown to influence dispute resolution (Ferrar et al., 2020), the current study focused on the conversation’s emotional tone. On one hand, based on a previous video chat study (Miller et al., 2017), it is probable that people with a self-view will communicate more pro-socially—for example, by using more positive emotional expression and less negative emotional expression—in order to meet their ideal standards and project a positive image to their conversation partner compared to those without a self-view. On the other hand, when in a disagreement, seeing oneself could motivate people to infer their negative attitudes toward their partner and thus show even more negative communication behaviors in part by attributing their discomfort to their partner. Considering the competing possibilities, the following research question is presented to examine the overall effect of a self-view on verbal emotionality, including emotional tone and positive/negative emotional expressions.

RQ2. How does having a self-view affect emotionality of conversation behaviors?

Method

Research design

This study conducted a lab-based experiment with two conditions (self-view vs. no self-view) between-subjects design. Two participants were paired and asked to have a conversation via a video chat program equipped with or without a self-view window. Following the methodology of previous studies that used scenario-based role-playing to make participants experience interpersonal disputes (Cropanzano et al., 1999; Stern et al., 1975), we asked participants to role-play either as a boss or an employee at an insurance company. By using a scenario-based approach, we were able to control for the content and duration of the conversation, allowing us to examine the pure effect of self-viewing ability differences on people’s reactions and communication outcomes. Three types of data were gathered throughout the research process. To begin, we recorded participants' physiological arousal and eye movement (gaze) data in real-time during the conversation. Second, following the conversation, self-report data were gathered, including evaluations of the self, partner, and solution. Third, all video chat conversations were transcribed for text analysis.

Participants

The study’s information was sent through an online paid participant pool affiliated with a Midwestern university in the United States. Because this pool was open to both university students and the general public, it contained a relatively diverse population. Eighty-eight participants took part in the research. Participants received $15 upon completion. Eight participants were excluded because they did not correctly answer the attention check question or did not follow the experiment instructions. The final N was 80 (40 dyads). The final sample had an average age of 32.56 (SD = 13.61; range = 19–69) and 67.5% of them were female. Participants identified themselves as Caucasian (71.3%), followed by Asian (12.5%), African American (5%), Middle Eastern (2.5%), and Hispanic (1.3%).

Procedure

For each dyad, each participant was directed to separate rooms upon their arrival at the lab. Following the informed consent procedure, participants were informed that they would participate in a role-play as either a boss or an employee at a workplace. The role was randomly assigned. Each participant was then given a one-page scenario describing a situation from either the boss’ or employee's perspective, adapted from a previous study (Shin et al., 2017). The boss scenario stated that as a division manager in an insurance company, the boss wants to discipline an employee who is the top salesperson but has attitude issues (e.g., being late to meetings, arrogance toward the manager). The employee scenario stated that the employee feels confident in their abilities as a top salesperson, that their actions are justified given their successful performance, and that increased work-related freedom is deserved. As the boss did not want to risk losing the employee to a competitor company and the employee did not want to risk missing out on a promotion opportunity at the current company, there was no simple solution for both, which made this scenario a difficult workplace conversation that could potentially turn into a conflict. Participants were given five minutes to read their own scenario and consider how to approach the conversation. The lab assistants entered each participant's room after five minutes to set up the measurement devices. The participants' non-dominant hand was equipped with finger sensors, and an eye tracker was calibrated to their gaze. On-screen videos were captured using screen recording software, and a Zoom video chat was launched.

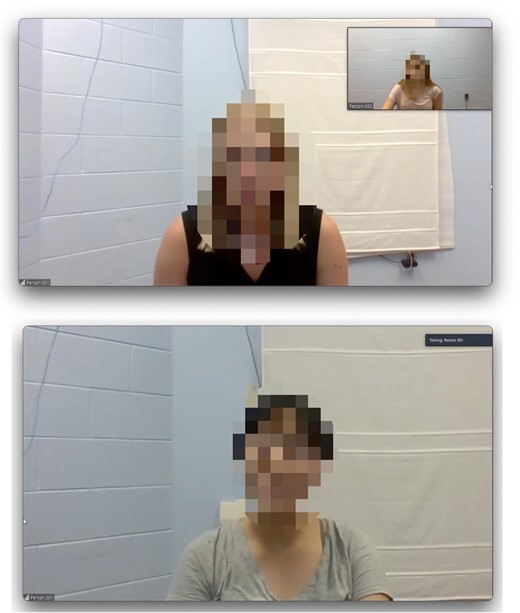

The video chat settings for dyads varied according to their experimental condition. For the self-view condition, a small self-view window was opened in the top right corner which took up approximately 1/9 of the screen (Figure 1), allowing both participants to view themselves during the video chat. The self-view window was presized to be consistent across all dyads. For the no self-view condition, this small self-view window was closed, and so participants in the no self-view condition were unable to watch themselves throughout the video chat. This configuration was completed prior to participants' arrival at the lab, and participants were instructed not to alter the video chat interface.

Screenshots of Video Chat with a Self-view (top) and without a Self-view (bottom).

Note. Faces were blurred for publication purpose.

After the lab assistants left the rooms, each dyad had approximately six minutes for conversation. Participants were also given the option of notifying lab assistants if their conversation lasted shorter than the six-minute time limit. After the conversation concluded, the eye-tracking and physiological arousal devices were disconnected, the screen-recording software was terminated, Zoom was closed, and each participant was asked to complete an online questionnaire. Following completion of the questionnaire, participants were informed about the study and compensated for their time.

Measures

Self-diagnostic ability for arousal

We measured (a) perceived arousal and (b) physiological arousal to see how accurately a person perceives one’s own physiological arousal state. Perceived arousal was measured by asking participants to indicate how they felt during the conversation on a 7-item, 7-point Likert scale (Matthews et al., 1990; 1 = Not all; 7 = Extremely). Examples of the items were: stirred up, anxious, tense, stressed, and nervous. The scores were averaged with higher scores meaning higher perceived arousal (α = .91, M = 2.95, SD = 1.33). Physiological arousal was measured by using a low-cost device offered on the market for biofeedback (IOM device). Specifically, the device measured interbeat interval (IBI), which is the time interval between the individual beat of the heart. The more aroused a person is, the shorter IBI in general. For the data analysis, we computed the mean of the IBI during the conversation (M = 709.65 milliseconds, SD = 114.18, range = 442.27–1067.91).

Diagnostic ability for partner’s liking

We measured (a) perceived liking from the conversation partner and (b) actual liking from the partner to see how accurately a person can perceive their partner’s liking toward them. Perceived liking was measured by asking participants to predict how their partner would think of them on a 3-item, 7-point semantic differential scale (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., 2002). The items included: negative (1) – positive (7), unfavorable—favorable, unlikable—likable. The scores were averaged with higher scores meaning higher perceived liking from the partner (α = .97, M = 5.00, SD = 1.45). Actual liking was measured by asking participants to rate their liking toward their partner on the same 3-item scale. Then, each participant’s averaged liking score was entered into their partner’s dataset as the actual liking from the partner (α = .96, M = 6.10, SD = 1.07).

Self-evaluation

Participants evaluated their own performance in the discussion on a 4-item, 7-point semantic differential scale originally developed for this study. The items were: communicated ineffectively (1) /effectively (7), handled the overall situation poorly/well, managed and expressed emotion poorly/well, and produced a bad/excellent solution to the problem. Because a factor analysis yielded a single-factor solution (Eigenvalue = 2.77, percentage of variance accounted for = 69.12%), the scores were averaged with higher scores meaning higher self-evaluation (α = .85, M = 5.31, SD = 1.10).

Partner evaluation

Participants rated their conversation partner on the task attraction scale (McCroskey & McCain, 1974; 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) that had 4 items on a 7-point Likert scale. The items included: “I have confidence in his/her ability to get the job done,” and “If I wanted to get things done, I could probably depend on him/her.” The scores were averaged with higher scores meaning higher partner evaluation (α = .77, M = 5.75, SD = 0.91).

Solution satisfaction

Participants rated the solution they reached in their video chat on a 4-item, 7-point Likert-type scale (adapted from Green & Taber, 1980). The items included: “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the quality of you and your partner’s solution?” (1 = extremely dissatisfied; 7 = extremely satisfied), “To what extent do you feel committed to you and your partner’s solution?” (1 = to an extremely small extent; 7 = to an extremely large extent). The scores were averaged with higher scores meaning higher solution satisfaction (α = .79, M = 5.08, SD = 1.15).

Emotionality of conversation

Conversations were transcribed and analyzed with the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count 2015 (LIWC). The LIWC results indicate the percentage of words that correspond to certain psychological characteristics such as emotionality, personality, and attentional focus (Tausczik & Pennebaker, 2010). The current study focused on the emotionality and thus used the following categories: positive emotion expression (e.g., great, thankful; M = 4.93, SD = 1.73) and negative emotion expression (e.g., unfortunately, wrong; M = 0.69, SD = 0.53). A summary measure of conversation tone that the LIWC provided was also used. According to the LIWC, the conversation tone was calculated by subtracting the LIWC score of negative emotion expressions from the LIWC score of positive emotion expressions and transforming the difference into a 0–100 scale, with higher scores meaning a more positive tone (M = 85.95, SD = 14.78). Given the nature of the scenario used, we also specifically looked at anxiety expression (e.g., unsure, struggles; M = 0.04, SD = 0.11) and anger expression (e.g., bothering, frustrating; M = 0.13, SD = 0.22).

Eye movement

Participants’ gaze during the conversation was measured by using The EyeTribe eye tracker device with a sampling rate of 30 Hz and an accuracy between 0.5° and 1°. The EyeTribe device was connected to the main computer with a USB and located underneath the computer screen in order not to disturb participants’ range of vision. The image frame of the video was divided into two parts (self-view window vs. rest of the screen). The frequency of entering the self-view area was counted (M = 21.05 times, SD = 13.49) and the average duration of staying in the self-view area for each time entering was computed for further analysis (M = 8.53 seconds, SD = 4.49). The frequency and duration of self-gaze were used to complement the hypothesis testing based on self-reports and conversation data.

Results

Covariate Check and Analysis Method

For analyses which use eye gaze data and physiological arousal data, we excluded 20 additional participants due to equipment measurement errors. Thus, the N used for testing H1 and supplemental analyses for each hypothesis and research question was 60 (30 dyads).1 All the other main analyses (H2, H3, H4, RQ1, RQ2) were conducted using self-report data and conversation data which were unaffected by the equipment measurement errors and thus the N was 80 (40 dyads) for these analyses. The decision for the different number of observations was made to avoid losing statistical power for each test. The means, standard deviations, and ranges of each variable for each condition are reported in Table 1.

| Dependent variable . | No self-viewing . | Self-viewing . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | Range . | M . | SD . | Range . | ||

| Perceived arousal | 2.89 | 1.26 | 1–5.71 | 3.03 | 1.43 | 1–5.86 | |

| Physiological arousal | 719.10 | 122.40 | 488.08–1067.91 | 695.48 | 101.48 | 442.27–897.38 | |

| Perceived liking | 4.90 | 1.45 | 1–7 | 5.11 | 1.45 | 2–7 | |

| Actual liking | 6.04 | 1.15 | 2–7 | 6.18 | 0.97 | 4–7 | |

| Self-evaluation | 5.57 | 0.95 | 2.75–7 | 4.99 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | |

| Partner evaluation | 5.94 | 0.93 | 2.75–7 | 5.51 | 0.84 | 4–7 | |

| Solution satisfaction | 5.18 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | 4.97 | 1.08 | 2.25–7 | |

| Positive emotion expression | 4.84 | 1.95 | 1.79–11.2 | 5.05 | 1.43 | 2.6–7.65 | |

| Negative emotion expression | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0–1.95 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0–1.79 | |

| Conversation tone | 83.11 | 16.62 | 42.9–99 | 89.42 | 11.45 | 48.8–99 | |

| Anxiety expression | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.65 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0–0.27 | |

| Anger expression | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0–0.99 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.62 | |

| Self-gaze frequency | 18.92 | 12.79 | 0–55 | 24.25 | 14.14 | 3–58 | |

| Self-gaze average duration | 7.26 | 3.89 | 0–15.2 | 10.44 | 4.73 | 4.64–23.2 | |

| Dependent variable . | No self-viewing . | Self-viewing . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | Range . | M . | SD . | Range . | ||

| Perceived arousal | 2.89 | 1.26 | 1–5.71 | 3.03 | 1.43 | 1–5.86 | |

| Physiological arousal | 719.10 | 122.40 | 488.08–1067.91 | 695.48 | 101.48 | 442.27–897.38 | |

| Perceived liking | 4.90 | 1.45 | 1–7 | 5.11 | 1.45 | 2–7 | |

| Actual liking | 6.04 | 1.15 | 2–7 | 6.18 | 0.97 | 4–7 | |

| Self-evaluation | 5.57 | 0.95 | 2.75–7 | 4.99 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | |

| Partner evaluation | 5.94 | 0.93 | 2.75–7 | 5.51 | 0.84 | 4–7 | |

| Solution satisfaction | 5.18 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | 4.97 | 1.08 | 2.25–7 | |

| Positive emotion expression | 4.84 | 1.95 | 1.79–11.2 | 5.05 | 1.43 | 2.6–7.65 | |

| Negative emotion expression | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0–1.95 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0–1.79 | |

| Conversation tone | 83.11 | 16.62 | 42.9–99 | 89.42 | 11.45 | 48.8–99 | |

| Anxiety expression | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.65 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0–0.27 | |

| Anger expression | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0–0.99 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.62 | |

| Self-gaze frequency | 18.92 | 12.79 | 0–55 | 24.25 | 14.14 | 3–58 | |

| Self-gaze average duration | 7.26 | 3.89 | 0–15.2 | 10.44 | 4.73 | 4.64–23.2 | |

Notes. The descriptive statistics for physiological arousal (interbeat interval) and self-gaze measures are based on the n = 60 dataset. All the other descriptive statistics are based on the n = 80 dataset.

| Dependent variable . | No self-viewing . | Self-viewing . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | Range . | M . | SD . | Range . | ||

| Perceived arousal | 2.89 | 1.26 | 1–5.71 | 3.03 | 1.43 | 1–5.86 | |

| Physiological arousal | 719.10 | 122.40 | 488.08–1067.91 | 695.48 | 101.48 | 442.27–897.38 | |

| Perceived liking | 4.90 | 1.45 | 1–7 | 5.11 | 1.45 | 2–7 | |

| Actual liking | 6.04 | 1.15 | 2–7 | 6.18 | 0.97 | 4–7 | |

| Self-evaluation | 5.57 | 0.95 | 2.75–7 | 4.99 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | |

| Partner evaluation | 5.94 | 0.93 | 2.75–7 | 5.51 | 0.84 | 4–7 | |

| Solution satisfaction | 5.18 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | 4.97 | 1.08 | 2.25–7 | |

| Positive emotion expression | 4.84 | 1.95 | 1.79–11.2 | 5.05 | 1.43 | 2.6–7.65 | |

| Negative emotion expression | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0–1.95 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0–1.79 | |

| Conversation tone | 83.11 | 16.62 | 42.9–99 | 89.42 | 11.45 | 48.8–99 | |

| Anxiety expression | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.65 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0–0.27 | |

| Anger expression | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0–0.99 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.62 | |

| Self-gaze frequency | 18.92 | 12.79 | 0–55 | 24.25 | 14.14 | 3–58 | |

| Self-gaze average duration | 7.26 | 3.89 | 0–15.2 | 10.44 | 4.73 | 4.64–23.2 | |

| Dependent variable . | No self-viewing . | Self-viewing . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | Range . | M . | SD . | Range . | ||

| Perceived arousal | 2.89 | 1.26 | 1–5.71 | 3.03 | 1.43 | 1–5.86 | |

| Physiological arousal | 719.10 | 122.40 | 488.08–1067.91 | 695.48 | 101.48 | 442.27–897.38 | |

| Perceived liking | 4.90 | 1.45 | 1–7 | 5.11 | 1.45 | 2–7 | |

| Actual liking | 6.04 | 1.15 | 2–7 | 6.18 | 0.97 | 4–7 | |

| Self-evaluation | 5.57 | 0.95 | 2.75–7 | 4.99 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | |

| Partner evaluation | 5.94 | 0.93 | 2.75–7 | 5.51 | 0.84 | 4–7 | |

| Solution satisfaction | 5.18 | 1.20 | 2.25–7 | 4.97 | 1.08 | 2.25–7 | |

| Positive emotion expression | 4.84 | 1.95 | 1.79–11.2 | 5.05 | 1.43 | 2.6–7.65 | |

| Negative emotion expression | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0–1.95 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0–1.79 | |

| Conversation tone | 83.11 | 16.62 | 42.9–99 | 89.42 | 11.45 | 48.8–99 | |

| Anxiety expression | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.65 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0–0.27 | |

| Anger expression | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0–0.99 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0–0.62 | |

| Self-gaze frequency | 18.92 | 12.79 | 0–55 | 24.25 | 14.14 | 3–58 | |

| Self-gaze average duration | 7.26 | 3.89 | 0–15.2 | 10.44 | 4.73 | 4.64–23.2 | |

Notes. The descriptive statistics for physiological arousal (interbeat interval) and self-gaze measures are based on the n = 60 dataset. All the other descriptive statistics are based on the n = 80 dataset.

Before the main analysis, we also checked whether the basic demographic variables (age, sex) as well as the duration of the discussion were needed to be included as covariates for hypothesis testing. Results showed that there was no significant difference between self-view and no self-view condition on participants’ age (t(77) = –0.41, p = .68), sex (χ2(1) = 1.22, p = .27), and the discussion duration in seconds (t(78) = –1.37, p = .18). Thus, these variables were not used as covariates in the main analysis.

Given the dyadic nature of the experiment, we first used a R package “lmerTest” (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) and a SPSS macro “MLmed” (Hayes & Rockwood, 2020) and ran mixed-effects models including dyad as a random-effects factor. However, results showed that dyadic influence was not a significant factor for most of the analyses. The only exceptions were for self-diagnostic ability and a conversation data variable (expressing positive emotion). Therefore, mixed-effects models were only used for self-diagnostic ability and conversation variables. In addition, investigations for the potential interaction with role showed participants’ role did not interact with self-view conditions on the dependent variables except conversation tone. Hence, the role was included as a moderator variable only for the analysis of conversation tone as a post-hoc analysis.2

Hypothesis test

Hypothesis 1 predicted that self-viewing would lead to higher self-diagnostic ability for arousal than no self-viewing. A mixed-effects model was performed by allowing random intercepts for dyad and using the REML method for fitting the model as the inclusion of the random-effects factor increased the model fit. The model had perceived arousal as a fixed-effects predictor and their IBI level as the outcome variable and was performed separately for each self-view condition. Results showed that for both self-view and no self-view condition, perceived arousal significantly predicted IBI (b = −30.37, SE = 11.43, t = −2.66, p = .02 for self-view; b = −37.44, SE = 16.24, t = −2.31, p = .03 for no self-view). Although the size of the standardized coefficients was greater for self-view (β = −.43, 95% CI −0.74, −0.11) than for no self-view (β = −.37, 95% CI −0.68, −0.06), 95% CIs largely overlapped. The marginal R2 which considers the variance explained by the fixed effects was only slightly greater for self-view (marginal R2 = .14) than no self-view condition (marginal R2 = .13). Thus, data was not supportive of H1. To further investigate whether self-gaze frequency and duration affected the relationship between perceived arousal and IBI, we looked at the interaction between perceived arousal and self-gaze frequency or duration on IBI for self-view condition. Results did not reveal any significant interaction.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that self-viewing would lower diagnostic ability for partner’s liking compared to no self-viewing. To test the hypothesis, a linear regression was conducted with predicted liking as a predictor and partner’s actual liking as an outcome variable, separately for self-view conditions. Results showed that for no self-view condition, predicted liking was significantly associated with actual liking, b = 0.24, SE = 0.11, t = 2.57, p = .01, R2 = .14. In contrast, for the self-view condition, there was no significant relationship between predicted liking and actual liking, b = 0.08, SE = 0.11, t = 0.67, p = .51, R2 = .01. Therefore, H2 was supported. In addition, when we looked at the interaction between predicted liking and self-gaze frequency or duration on actual liking for the self-view condition, results did not reveal any significant interaction.

Hypothesis 3 predicted that self-viewing would decrease self-evaluation compared to no self-viewing. An independent t-test result showed that people with a self-view (M = 4.99, SD = 1.20) had lower self-evaluation than those without a self-view (M = 5.57, SD = 0.95), t(78) = 2.42, p = .02, Cohen’s d = 0.54. Therefore, H3 was supported. We further investigated whether the gaze data was related to self-evaluation. A multiple regression analysis was conducted on self-viewing participants to investigate how the frequency of entering the self-view area and the average duration of staying in the self-view area predicted self-evaluation. Results showed that the regression model was not statistically significant, F(2, 21) = 0.88, p = .43, R2 = .08. The frequency of self-view gaze (b = 0.01, SE = 0.02, t = 0.49, p = .63) and the average duration of self-view gaze (b =–0.07, SE = 0.05, t = −1.23, p = .23) were not significant predictors for self-evaluation. This result suggested that self-evaluation is affected not by the frequency or duration of self-view gaze, but rather by the presence (vs. absence) of the self-view screen.

Research question 1 investigated whether self-viewing affected partner evaluation. An independent t-test was conducted to compare the self-view condition and the no self-view condition on partner evaluation. Results showed that self-viewing (M = 5.51, SD = 0.84) decreased partner evaluation compared to no self-viewing (M = 5.94, SD = 0.93), t(78) = 2.17, p = .03, Cohen’s d = 0.49. In addition, a multiple regression on the self-view condition with the self-gaze frequency and duration as predictors was performed to investigate the influence of self-gaze on partner evaluation. The regression model was not statistically significant, F(2, 21) = 0.01, p = .99, R2 = .001. The self-gaze frequency (b = -0.002, SE = 0.01, t = –0.14, p = .89) and the average duration of self-gaze duration (b = 0.004, SE = 0.04, t = 0.09, p = .93) were not significant predictors for partner evaluation. In sum, partner evaluation was negatively affected by the presence of a self-view screen, but not by the frequency or duration of self-gaze.

Hypothesis 4 predicted that self-viewing would lower solution satisfaction via lowering self-evaluation. A mediation analysis was conducted by using Hayes’ PROCESS (Hayes, 2017) Model 4 with dummy-coded self-view condition (0 = no self-view; 1 = self-view) as the independent variable, self-evaluation as the mediator, and solution satisfaction as the dependent variable. Results showed that the indirect effect of self-viewing on solution satisfaction via self-evaluation was significant, b = −0.31, SE = 0.14, 95% 5000 bootstrap CI (−0.61, −0.05). Specifically, self-viewing decreased self-evaluation compared to no self-viewing, b = −0.58, SE = 0.24, t = −2.42, p = .02, and self-evaluation positively predicted solution satisfaction, b = 0.53, SE = 0.11, t = 4.97, p < .001. Thus, H4 was supported. The total effect of self-viewing on solution satisfaction was not significant, b = –0.22, SE = 0.26, t =–0.84, p = .40 and the direct effect was not significant, b = 0.09, SE = 0.23, t = 0.39, p = .70. In addition, using either self-gaze frequency or duration as an independent variable, the same mediation analysis was conducted. Self-gaze frequency and duration did not have a significant total effect and indirect effect through self-evaluation on solution satisfaction.

Research question 2 investigated whether self-viewing would affect emotionality of conversation. A mixed-effects model was performed by allowing random intercepts for dyad and using the REML method for fitting the model as the inclusion of the random-effects factor increased the model fit. The dummy-coded self-view condition (0 = no self-view; 1 = self-view) was entered as a predictor and each indicator for conversation behavior was an outcome variable. Results showed that there was no significant difference between self-view conditions on the overall conversation tone (b = 6.30, SE = 3.68, t = 1.71, p = .09), the expression of positive emotion (b = 0.21, SE = 0.46, t = 0.46, p = .65), and anxiety expression (b = −0.03, SE = 0.02, t = −1.31, p = .19). However, self-viewing decreased the expression of negative emotions (b = −0.28, SE = 0.13, t = −2.09, p = .04) and anger expressions (b = −0.15, SE = 0.05, t = −2.80, p = .008). When self-gaze frequency and duration were entered as predictors, results showed no significant effects on conversation behaviors.

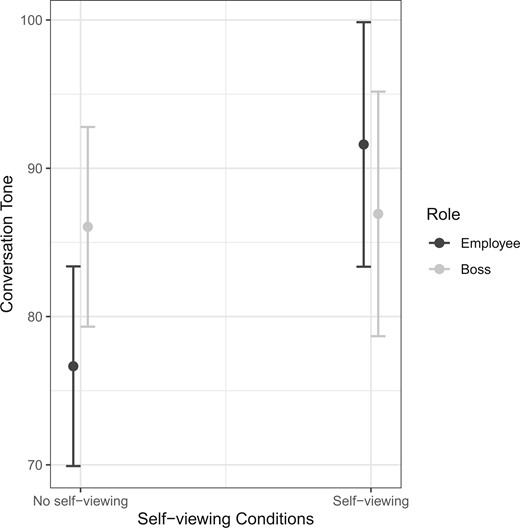

In a post-hoc analysis including participants’ role (0 = employee; 1 = boss) as another predictor, we also found that the role interacted with self-view conditions on conversation tone, b = –13.27, SE = 5.31, t = –2.50, p = .02. Simple-effects analysis probing the interaction pattern showed that, for employees, those with a self-view used more positive conversation tone (M = 91.99, SE = 3.37) than those without a self-view (M = 79.06, SE = 3.04), t(69.1) = 2.85, p = .006, whereas there was no significant effect of a self-view on conversation tone for bosses (M = 86.84, SE = 3.37 for self-view; M = 87.17, SE = 3.04 for no self-view), t(69.1) = −0.07, p = .94 (see Figure 2 for interaction plot).

Interaction Plot for Conversation Tone.

Note. The error bars represent 95% CI. The higher the value on the Y-axis, the more positive the conversation tone is.

Discussion

The current study examined the effects of self-viewing in a workplace interpersonal conversation via video chat. The findings indicated that self-viewing in general had negative impacts on perceptions of self and others. Individuals who had a self-view in video chat had a lower diagnostic ability for partner's liking, a lower self-evaluation, and a lower partner evaluation than those who did not have a self-view. Additionally, self-view decreased solution satisfaction by lowering self-evaluation. In conversation data, we discovered the positive effects of self-viewing in video chat. Self-viewing reduced negative emotional expressions, particularly anger expressions. However, further interaction analysis of conversation tone indicated that this beneficial effect varied according to a person's role.

Theoretical and practical implications

To begin, the current study discovered that the ability to view one's own performance via video chat influences how positively one evaluates one's own performance. This finding accords with the premise of objective self-awareness (Duval & Wicklund, 1972). Our findings imply that when people are involved in unfavorable interpersonal confrontations, their self-awareness is more likely to have a negative effect on self-evaluation. People with self-view are better able to observe their performance in handling a difficult conversation and thus have a greater chance of detecting any incapacity or errors that are not up to par, leading to a decrease in self-evaluation. Our result on self-evaluation also suggests a contextual effect of self-viewing in video chat. In a previous study that involved a getting-to-know conversation (Miller et al., 2017), participants with a self-view rated their own performance higher in terms of delivering affection and having a deeper conversation than participants without a self-view, which is the opposite of what we found in the current study. This distinction suggests that the effects of self-viewing are likely to vary according to the type of conversation (e.g., casual vs. formal) or the topic of the conversation (e.g., topic difficulty).

Second, this study discovered that self-viewing indirectly decreased solution satisfaction via lowering self-evaluation. This indicates that when people believed they performed worse due to watching their own behaviors, they were less satisfied with the discussion outcome. This finding is consistent with prior research demonstrating positive associations between self-esteem or self-efficacy and job or relationship satisfaction (Chang & Edwards, 2015). The mediating effect via self-evaluation is particularly intriguing given that neither the total effect nor direct effect of self-viewing on solution satisfaction was significant. On one hand, it implies that self-viewing in video chat does not affect people to experience a reduction in self-evaluation to the same degree. That is, those who are more sensitive to self-viewing could be more disadvantaged by being more critical toward themselves and hence be less satisfied with the result. Future research is thus needed to clarify factors that either promote or reduce the sensitivity toward self-viewing or the moderators for the linkage between self-viewing and self-evaluation, such as various individual differences (e.g., interpersonal anxiety) or situational factors (e.g., intercultural encounter). On the other hand, the result also suggests a possibility for another route through which self-viewing affects solution satisfaction, but in the opposite direction to that of self-evaluation. For example, by being able to see two people together simultaneously, a self-viewing screen may have enhanced the feeling of co-presence with the partner, which is known to enhance communication satisfaction (Nowak et al., 2009). Exploring the alternative path through which a self-viewing screen positively affects result satisfaction may be a worthwhile future direction for research.

Third, this study established that self-viewing impairs people's ability to diagnose their partner's attitude. In other words, when a self-view was present in a video chat, people appeared to lose their ability to accurately perceive their partner's liking for themselves, which supports the concept of limited attention capacity (Lang, 2006) and automatic attention to self-relevant stimuli (Tacikowski & Nowicka, 2010). When people are concentrating on a single stimulus, they are frequently unaware of other events occurring concurrently in their environment and misreport the occurrence of other events (Most et al., 2001). Thus, in a video chat, the self-view may have captured the user's attention, reducing their ability to interpret their partner's words and behaviors as intended. The inability to infer a partner's attitudes may impede dispute resolution by reducing the likelihood of perspective-taking which is known to promote more effective resolution with more joint gains (Galinsky et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2019). This lower partner-diagnostic ability may also partially explain why people with a self-view had a lower partner evaluation, as they could have projected their own discomfort from the difficult conversation onto their partners when they become unclear about their partner's actual thoughts, which accords well with self-perception theory (Bem, 1972). Meanwhile, self-viewing did not affect people’s ability to diagnose their own physiological arousal level. Regardless of the presence (vs. absence) of a self-viewing screen, perceived arousal significantly predicted the physiological arousal. This indicates a possibility that a video chat (or maybe any other mediated communication setting) provides an environment where one can quite accurately predict their own physiological arousal level due to the comfort physical distance provides. If so, additional information such as a self-view would not increase the accuracy to a significant degree, as was the case for the current study. Previous research showing that people were less likely to overestimate their physiological arousal when in a video chat compared to face-to-face conversation seems to support this possibility (Shin et al., 2017).

Fourth, this study discovered that self-viewing has positive effects on conversation behaviors, such as decreased negative emotion expressions, particularly anger expressions. On the surface, the positive effect on conversation behaviors may seem inconsistent with the overall negative effects on perceptual outcomes. However, this difference in communication behaviors can be interpreted as an attempt to conform to ideal internal standards, which is consistent with the objective self-awareness theory’s argument that self-awareness leads to behaviors to reduce the misfit between the ideal self and the observed self (Duval & Wicklund, 1972). In other words, the negative self-perceptions derived from self-viewing could have motivated people to reduce negative expressions as a means to restore their self-image. Interestingly, our post-hoc analysis also revealed that this potentially beneficial effect of self-viewing can be somewhat limited by the role that each individual plays. In fact, the effects of self-viewing were not varied by the role, except for the conversation tone, which may indicate that overt behaviors are more susceptible to the influence of the role than inner perceptions. Specifically, when a self-view was provided, whereas employees altered their tone to be more positive, bosses did not alter their conversational tone. Compared to bosses, employees could have felt more need for impression management when there was a self-view. This role-dependent interaction effect suggests that when there is a power differential in a relationship, such as at work or in a personal setting, individuals with a lower power status are more likely to be influenced by a self-view and thus manage and control their behaviors to a greater extent than individuals with a higher power status. It also implies that the ideal standards people strive to achieve during periods of increased self-awareness may reflect social norms such as ‘this is how an employee or a boss should behave’ rather than personal desires. If this is the case, a media environment that constantly raises people's awareness of themselves may disproportionately favor those who can voice their opinions with less concern for impression management. Our study thus calls for more research for unknown consequences of apparently benign or taken-for-granted features of communication channels.

Fifth, it is worthwhile to mention that our study did not reveal any differential effects of self-viewing frequency and duration for any of the outcome variables. In other words, all the largely negative effects found for self-viewing in the current study can be attributed to the availability of a self-view screen in a video chat rather than how frequently or how long on average one looks at the self-view screen. This result implies that the mere presence of a self-view screen could put people in a different frame of mind at the outset to focus more on themselves internally rather than others. At the same time, it may indicate the effect of a self-viewing screen has a rather low threshold to exert, which accentuates the need for extra care of designing a virtual communication channel like a video chat.

In sum, the current study contributes to the theoretical understanding of the effect of self-viewing in video chat and provides practical implications as well. Theoretically, objective self-awareness theory and self-perception theory received support. Corresponding well with the claims of objective self-awareness theory, self-viewing in video chat seemed to have led people to be more self-aware and become more critical toward themselves, which is reflected in lower self-evaluation. Self-viewers also decreased negative emotional expressions more, supporting the theory’s argument that restorative behavior change would ensue following the critical assessment toward themselves. In addition, self-perception theory’s claim that people infer their attitudes toward others based on their self-observation was supported by our finding that self-viewers evaluated their partner more negatively.

The effects of self-viewing a video chat could also be understood in relation to a theory of communication visibility (Treem et al., 2020). The theory posits that CMC channels make communication behaviors that were previously invisible and thus the ability to manage such visibility can be important. While the theory mainly talks about the potential visibility of one's actions to others, the present study extends the theory by recognizing an additional visibility affordance CMC brings—that is, the possibility of viewing self-action. The immediate audience of communication in CMC can include the self, which apparently leads to various perceptions including the performance of the self, others, and the task at hand. Our study also demonstrates that the self-communication visibility triggered impression management as shown in the difference in conversation behaviors depending on the role. In sum, our study emphasizes the importance of communication visibility in CMC by evidencing the effects of self-communication visibility.

Practically, the current study presents significant implications for interpersonal communication through visually mediated channels. Our findings suggest that when individuals anticipate a difficult conversation that may trigger interpersonal conflicts or anxiety-provoking topics, it is preferable to disable the self-view screen in a video chat. Lack of a self-viewing opportunity can increase one's confidence in one's performance, resulting in a more satisfactory outcome. Additionally, it can improve an individual's ability to accurately gauge their conversation partner's attitude and foster a more positive attitude toward the partner. In some ways, disabling the self-view function in a video chat removes an artificial barrier erected by technology and reintroduces people to the sensation of in-person communication while still allowing for remote human relationships to be maintained.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Some limitations of the current study should be noted. To begin, the current study did not directly assess and test potential mediating variables, such as objective self-awareness, for the effect of self-viewing. The purpose of this study was to determine the existence of self-viewing effects, not to elucidate their mechanism. Measuring psychological mediators as a next step will be beneficial in clarifying the mechanism of the effects observed in this study.

Second, several experimental design decisions could be improved in future research to raise the generalizability of the current findings. The current research design enabled us to control for potential confounding variables such as the conversation topic, pre-existing relationships, and conversation length. However, it certainly has the disadvantage of the artificial nature of role-playing scenario which could have created a ceiling effect when compared to more intense real-life workplace disputes. Relatedly, our workplace scenario could have been more engaging and felt more realistic for the participants who had workplace experience before and thus affected their outcomes more strongly. Although we excluded participants whose conversation transcripts showed evidence of low engagement (e.g., discussing what they would do in the situation rather than role-playing; n = 6), it would be beneficial for future research to measure and control for the previous experience related to a conversation scenario.

Third, our sample size was small which could have increased the Type II error, being less prone to detect subtler true differences. Although it also suggests some level of robustness against the possibility of Type I error, a future study with a greater sample size would be helpful to re-test the non-significant findings in this study such as the effects of self-gaze frequency and duration, especially given the challenges we had with the measuring equipment.

Fourth, despite our effort to collect a diverse sample by opening the recruitment to the public rather than only college students, our sample is still U.S.-based and a majority of them (71.3%) are Caucasians. Replications and extensions of the current findings in different countries would be beneficial to increase external validity.

Fifth, potential moderators such as the general level of experience with video chat or a self-view should be measured and investigated in future research. Although our participants did not express any difficulty in using a video chat to communicate with their partner, it is still possible that their differential familiarity with the technology had impacted their experience.

Lastly, we hope our research will spark more focused research on the differential effects of self-viewing depending on the role one plays in the context given our unexpected finding regarding the role.

Conclusion

Video chats have evolved into an indispensable mode of communication for people managing various aspects of their relationships remotely. This study provides the first experimental evidence that self-viewing capability in a video chat, which is a standard feature of most video chat programs, can have some detrimental effects on the process and outcome of interpersonal conversation. The ostensibly convenient media capability of monitoring one's appearance and actions in real time resulted in more unsatisfactory outcomes. Indeed, although computer-mediated communication provides a new way to make communication activities visible that were previously hard to observe (Treem et al., 2020), we need more nuanced, systematic investigations to know and appropriately use such visibility for achieving desired relational outcomes.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by University of Hawaii at Manoa and the Institute of Communication Research at Seoul National University.

Notes

The descriptive statistics for physiological arousal and eye gaze data reported in the Measurement section were also based on the n = 60 dataset.

We also checked statistical assumptions for ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions such as normal distribution of residuals (kernel density plot, Q-Q plot, P-P plot, Shapiro-Wilk test), homoscedasticity (residual-versus-fitted plot), linearity (scatter plot), and multicollinearity (VIF) when applicable. We did not find strong evidence of violations of the assumptions except for the normal distribution of residuals. However, transformations of the data using log or square root did not improve the normality or did not change the hypothesis testing results even when they improved the normality. Thus, for easier interpretation of the results, we presented the analysis results based on non-transformed data.