-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sarit Navon, Chaim Noy, Like, share, and remember: Facebook memorial Pages as social capital resources, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 28, Issue 1, January 2023, zmac021, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac021

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study focuses on users’ practices involved in creating and maintaining Facebook memorial Pages by adapting the theoretical perspective of the social capital approach. It examines 18 Pages in Israel, which are dedicated to ordinary people who died in nonordinary circumstances. We employ qualitative analysis based on a digital ethnography conducted between 2018 and 2021. Our findings show how memorial Pages serve as social capital resources for admin users. Admins negotiate Facebook affordances when creating, designing, and maintaining such Pages. They discursively position the deceased as a respectable public figure worth remembering and their followers, who are otherwise strangers, as vital partners in this process. The resources followers provide range from economic capital and practical support to solidarity and emotional support. Finally, we point at the perceived connection users make between visible/measurable online engagement (Like, Share, Follow), and cognitive or emotive implications—public memory, recognition, and esteem.

Lay Summary

Pages is one of the communication channels that Facebook offers for businesses and public figures who seek to increase their digital presence. However, some users creatively adapt Pages to their needs, one of which is to memorialize and publicize ordinary people. In this study, we closely examine 18 memorial Pages, which were created in memory of ordinary people who died in nonordinary circumstances. Yet despite the anonymity of the deceased, these Pages reach a vast number of followers, and generate and display extensive activity both online and offline. Our findings depict how users lead this process, from the early stages of creating and naming the Page—against Facebook's official policy—to the maintenance of the Page activity and their relationship with followers. These users, who become administrators (admins), use their network of followers to accumulate various resources: money donations, physical attendance in memorial events, emotional support, and more. These resources amount to the social capital that admins generate. Admins portray the deceased as a respectable person, whose story carries special social significance and collective moral value. They then establish a link between digital engagement metrics (Likes, Shares), and cognitive or emotive implications—public memory, recognition, and esteem.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, online practices of death, mourning, and memorialization have grown into a vibrant field of interest and research. Studying the intersection of death and digital media sheds light on novel commemorative practices, affective performances, and oscillations between personal and public spheres. As such, it contributes to our understanding of social practices of remembrance, underlined by the questions: Who is worthy of remembrance, and why and how are they remembered?

A major site of online mourning and memorialization is the social networking site Facebook. The oscillations between personal and public spheres are integrated into Facebook’s internal logic and infrastructure. As a multifunctional platform, Facebook brings together several distinct communication channels, also known as “subplatforms” (Navon & Noy, 2021). Facebook’s three main subplatforms are Profiles, Groups, and Pages. Profiles are personal accounts that represent the user as an individual; Groups allow interaction of several users, usually around a specific shared interest; and Pages serve as public channels, allowing a more unidirectional communication with broad audiences.

The official aim of Pages is to serve businesses, communities, organizations, and public figures who seek to increase their digital presence and connect with audiences and fans. It is an essentially public subplatform that is visible to anyone on Facebook by default (as opposed to Profiles or Groups) and may have an unlimited number of followers. Pages’ administrators (admins) manage the interaction with the followers and the content on the Page. Interestingly, users commonly employ Pages in a memorial capacity and create Pages to memorialize and publicize ordinary people.

In this article, we look at memorial Pages that are dedicated to ordinary people who died in nonordinary circumstances (terror attacks, murder, suicide, etc.). Our data consist of 18 cases, all of whom are Israeli. The aim of this study is to examine the practices involved in creating and maintaining memorial Pages from the theoretical perspective of the social capital approach. We explore how creators of memorial Pages view the role of the Page, their motivations, and their relations with different audiences, such as strangers (Marwick & Ellison, 2012). We further analyze how admins interact with their network of followers and the various resources they accumulate through this process—from economic capital and practical support to solidarity and emotional support.

Literature review

Online mourning and memorialization

Online practices of remembrance and memorialization emerged in the mid-1990s, initially in the form of virtual cemeteries and private Web memorials (Roberts, 1999). This “first generation” of digital practices, as Walter (2015) terms it, “changed surprisingly little” compared to earlier offline practices (p. 10). It was only in the early to mid-2000s, with the rise of social media, that things have significantly changed.

Social media, and social network sites (SNSs) in particular, afford new means for grieving and commemorating, and influence the experience of death both online and offline. Brubaker et al. (2013) identified three expansions of death and mourning that SNSs afford and facilitate: a spatial expansion in which physical barriers to participation are dissolved; a temporal expansion that refers to the immediacy of information enabled by SNSs; and a social expansion that results in a context collapse and the inclusion of the deceased within the social space of mourning (see also Marwick & Ellison, 2012).

The intense social nature of social media is shaped by its inherent features of sharing, performance, and interaction. Sharing can be appreciated through different logics, while on SNSs the primary logic is communicative and not distributive (when someone shares her feelings or belief, she is not left with less). On SNSs, sharing is telling, where “fuzzy objects of sharing” are nonetheless associated with giving and caring (John, 2013). These sharing–telling practices involve multiple modes and strategies of self-presentation, identity negotiation, and performance (Papacharissi, 2010), which inevitably lead to intensified engagement and participation.

This is true also of mourning and memorialization contexts, where engagement and participation can be viewed as a demonstration of communality and social support (Döveling, 2015; Walter, 2015). Alternatively, engagement and participation may also indicate social pressure and competition over who has the most significant contributions or the right to portray the deceased (Carroll & Landry, 2010; Marwick & Ellison, 2012; Walter, 2015). Social dynamics and engagements are complex, determined in part by the specific media (sub)platform and its affordances.

Studies of mourning and memorialization examine various social media platforms, including MySpace (Carroll & Landry, 2010), YouTube (Harju, 2015), Instagram (Gibbs et al., 2015), Twitter (Cesare & Branstad, 2018), and TikTok (Eriksson Krutrök, 2021). However, the most dominant platform, both in terms of research and of user practices, is Facebook. The vast number of dead users along with the various practices and rituals that living users perform qualifies Facebook as a “current center of gravity” for the discussion of online mourning and memorialization (Moreman & Lewis, 2014, p. 4).

Mourning and memorialization on Facebook

Studies of mourning and memorialization on Facebook point at multiple practices and uses. Such practices may chronologically commence with death announcements and the posting of information about memorial services (Babis, 2021; Carroll & Landry, 2010, respectively), to subsequent and more continuous practices, such as visiting the deceased’s Profile and posting messages as a way to commemorate, express emotion, and remember special occasions (Pennington, 2013; Moyer & Enck, 2020, respectively).

An additional common practice, which lies at the heart of our current study, is the creation of memorial Pages. These Pages may be dedicated to individual subjects, groups of people, animals, and things such as places (Forman et al., 2012; Kern et al., 2013). They enable “para-social copresence” and continuing bonds (Irwin, 2015), as well as public presence of the deceased and engagement with strangers (Kern et al., 2013; Kern & Gil-Egui, 2017).

Rossetto et al. (2015) point to three themes or functions that mourning and memorialization on Facebook possess: news dissemination, preservation, and community. News dissemination describes sharing or learning information about a death through Facebook. Preservation refers to the continued presence of the deceased and maintaining communication and connection with them. Lastly, the community theme refers to the connection and communication with people other than the dead. It includes connecting with other mourners, seeking and offering social support, and expressing one’s feelings and thoughts, while at the same time facing a challenge to privacy.

One way to face this privacy challenge and negotiate boundaries is through Facebook subplatforms. In a study of mourning and memorialization practices across Facebook’s subplatforms, Navon and Noy (2021) outline a spectrum that ranges from private to public and accordingly from a more personal sphere of mourning to a larger and more institutional sphere of memorialization. Located on one side of the spectrum, Profiles are characterized by expressive and emotive communication, hence turning with time into personal mourning logs on the bereaved’s Profile and online mourning guestbooks on the deceased’s Profile.

Located on the spectrum’s other side, Pages possess a distinctly public quality and serve as online memorialization centers where the deceased becomes an icon and is portrayed in one dominant way. Finally, Groups are positioned in-between, possess a hybrid nature, and combine self-expression and emotional sharing along with more public aspects. This results in Groups affording the revival of once-prevalent bereaved communities (Navon & Noy, 2021).

The triadic spectrum we outlined corresponds with the three levels of social death that Refslund and Gotved (2015) have put together. First, the individual level focuses on the personal loss (Profiles); second, the community level revolves around an extended network: relatives, neighbors, colleagues, and other acquaintances of the deceased (Groups); and third, the cultural or public level (Pages), refers to the death of people not personally known. According to the authors, this level “generates memorial practices that relate to the way of death (e.g., murder and traffic) or how they were appreciated in life (e.g., celebrities)” (p. 5). Similarly, Walter (2015) suggests the concept of public mourning, pertaining to either high-status figures or to ordinary people who die in tragic circumstances. In this study, we examine the latter. We look at public memorial Pages created in memory of ordinary people that nonetheless generate public mourning.

Analyzing Facebook memorial Pages, Marwick and Ellison (2012) discuss the publicizing of the deceased in terms of impression management strategies and conflicts among users. They focus on context collapse, negotiation of visibility, and the four characteristics of social media: persistence, replicability, scalability, and searchability (see boyd, 2010). They conclude with a recommendation for future research that will employ qualitative methods to explore how creators of memorial Pages view the role of the Page, their motivations, and their view of different audiences, such as strangers (p. 398). Our current research does precisely that and seeks to provide answers to these questions. However, while Marwick and Ellison (2012; also Sabra, 2017) frame their investigation in terms of context collapse, we suggest viewing Facebook memorial Pages via the social capital approach. We focus on admins’ (Page creators’) practices, which result in the accumulation of social capital.

Social capital and social media

Defining the term social capital is challenging, in part because it has received multiple definitions during the last few decades. Kritsotakis and Gamarnikow (2004) observe that “defining social capital is rather problematic” (p. 43); Williams (2006) adds that it is a “contentious and slippery term” (p. 594), and Xu et al. (2021) conclude that it is an “encompassing yet elusive construct” (p. 362).

One of the influential formulations of social capital was proposed by Bourdieu (1986), as part of his conceptualization of different types of capital and related systems of exchange. For Bourdieu (1986), “the distribution of the different types and subtypes of capital at a given moment in time represents the immanent structure of the social world” (p. 242). In line with his practice-centered approach and his dialectic view of the structure–agency relations (like Giddens, 1984), Bourdieu puts much emphasis on the role of constant social interaction (micro) in maintaining social structures (macro). He accordingly sees social capital as “potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships” (Bourdieu, 1986, p. 248).

Another oft-cited and productive definition emerges from Putnam’s (2000) view of social networks from the perspective of political science and civic engagement. Putnam (2000) draws a distinction between two main types of social capital: “bridging” and “bonding.” The first describes broader, more diverse, and inclusive relations, which are often more tentative, while the latter concerns more exclusive relations, which are less diverse and more cohesive. The two concepts echo Granovetter’s famous (1973) observation concerning “weak ties” versus “strong ties” (which, again, are wittingly or not, goal-oriented).

In a related manner, Williams (2006) notes that strong ties supply a “getting by” type of network (e.g., family and close friends), while weak ties supply a “getting ahead” social environment (e.g., distant acquaintances, social movements). He further suggests that different types of social networks can predict different types of social capital. More recently, Xu et al. (2021) conclude that “social capital consists of both social networks and resources derived from social networks” (p. 363, emphasis in original). Hence, we now turn from describing network characteristics to describing measurements of their outcomes or resources.

Williams (2006) operationalizes measures of assessing social capital outcomes by addressing the two types of social capital Putnam (2000) discerned. As per bridging social capital, he developed a questionnaire based on several criteria, one of which is contact with a broad range of people; as per bonding social capital, he builds on several dimensions, including emotional support and the ability to mobilize solidarity. Xu et al. (2021) found that network features, specifically tie strength and communication diversity, result in different levels of emotional, practical, and informational support.

Theories of social capital have been studied extensively in relation to social media, so much so that they are recognized as a leading area of interest in the field (Stoycheff et al., 2017). One stream of scholarship has explored the effect of social media affordances on social capital outcomes. The term “socio-technical capital” (Resnick, 2002), captures these relations, arguing that individual users enjoy a greater ability to accrue social capital in the age of social media, as it becomes easier to maintain and create new connections.

Indeed, studies have found a positive association between the usage of SNSs and perceived access to social capital resources (Ellison & Vitak, 2015). Ellison and Vitak (2015) observe that recent studies further examined the “specific kinds of activities that are predictive of social capital” (p. 210, emphasis added) and not only general measures of use. They point to two main factors that appear to be most significant to social capital gain: the size and composition of the network and how users communicate with that network, that is, patterns of interaction. They stress that, “social capital is derived from interactions with one’s network” (p. 210, emphasis in original).

In this article, we view social capital as potential resources that are produced through interactions in a structured social network. These resources may possess bonding or bridging social capital qualities, including emotional, practical, and informational support (Bourdieu, 1986; Putnam 2000; Xu et al., 2021). Rather than looking separately at resources or network characteristics, our focus is on social capital processes, that is the relations between the social network and the outcomes or resources that emerge from it. While some existing literature examines these relations and processes, we add a third element, namely the social network platform. This concerns how specific affordances enable and motivate social capital processes, and how users utilize affordances to position themselves and others in ways that encourage accumulation. Positioning is constitutive of social capital processes (Basu et al., 2017), and in line with our platform-centered approach, we take it to include users’ practices of discursive positioning and the positioning that the platform itself performs. Within this framework we look at Pages’ affordances (Page category, About, followers’ count, etc.) as well as users’ practices and activities, discourse, and patterns of interaction. Together, the findings provide fruitful insights into social capital processes, memorialization practices, and public remembrance on SNSs.

Method

Sampling

The research sample includes 18 Facebook Pages, which we observed during three years.1 All the Pages were created in memory of ordinary people who died in nonordinary circumstances. Typical examples include a woman who was murdered by her male partner, a high-school student who committed suicide as a result of cyberbullying, a female backpacker who died in a bus accident during a trip to Nepal, victims of terrorist attacks, and fallen soldiers (males and females). Table 1 presents key details of all the cases, including the cause of death. To stress, none of these commemorated individuals were public figures or known publicly. The cases include 12 men and 7 women (one case refers to the death of female and male spouses), ranging in age between 15 and 55, with an average of 25.6 (Table 2). The Pages were created between January 2011 and October 2016, and are all in Hebrew. All the translations are ours.

| Page name . | Followers’ count . | Category . | Cause of death . | Age . | Gender . | Date of Page creation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Memory of Yoram Samson RIP | 19K | Community | Under investigation—accident, suicide, or murder | 23 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of ACOP Eytan Bar | 7.7K | Government official | Suicide | 55 | Male | July 5, 2015 |

| In Memory of Shelly David RIP | 10.5K | Community | Murder | 20 | Female | May 2, 2014 |

| Remembering Talya Nadav with a smile | 4K | Community | Car accident | 21 | Female | May 24, 2015 |

| Osnat Shemesh—The sun will never set | 10.6K | Community | Bus crash in Nepal | 22 | Female | November 6, 2014 |

| David Mishori RIP | 40.3K | Interest | Suicide after cyberbullying | 15 | Male | January 5, 2011 |

| Remembering Or—In Memory of Or Michaelovich | 40.3K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | August 12, 2014 |

| In the Memory of Zinedine Salman | 5.5K | Community | Officer/policeman, killed in line of duty | 30 | Male | November 19, 2014 |

| Eli and Nurit Harari H.Y.D. (God will avenge their blood) | 3.4K | Community | A drive-by shooting on the road in Samaria | 30 | Female and male spouse | October 1, 2015 |

| In Memory of Cpl. Hodaya Cohen RIP | 12K | Community | Terror attack in Jerusalem | 19 | Female | February 3, 2016 |

| Avi Baruch—we will remember you forever | 26.5K | Community | Shooting terror attack in Tel Aviv | 26 | Male | January 4, 2016 |

| In the way of Gal—In Memory of 1SG Gal Levi RIP | 4K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 19, 2015 |

| In Memory of Beni Ram RIP | 18K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of Naveh Goldstein RIP | 3.8K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 23 | Male | November 22, 2014 |

| A Page In Memory of Ofek Noy H.Y.D (God will avenge his blood) | 8.1K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 22, 2014 |

| Always remembering Yoni Kedem H.Y.D. (God will avenge his blood) | 13K | Public Figure | Yasam officer (Police Special Patrol Unit), died in line of duty | 29 | Male | October 16, 2016 |

| Sapira Sandler RIP—the official Page | 3.2K | Interest | Murder | 37 | Female | June 3, 2012 |

| Remembering Kate Tomer | 1.2K | Public Figure | 2006 Lebanon War | 26 | Female | July 7, 2012 |

| Page name . | Followers’ count . | Category . | Cause of death . | Age . | Gender . | Date of Page creation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Memory of Yoram Samson RIP | 19K | Community | Under investigation—accident, suicide, or murder | 23 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of ACOP Eytan Bar | 7.7K | Government official | Suicide | 55 | Male | July 5, 2015 |

| In Memory of Shelly David RIP | 10.5K | Community | Murder | 20 | Female | May 2, 2014 |

| Remembering Talya Nadav with a smile | 4K | Community | Car accident | 21 | Female | May 24, 2015 |

| Osnat Shemesh—The sun will never set | 10.6K | Community | Bus crash in Nepal | 22 | Female | November 6, 2014 |

| David Mishori RIP | 40.3K | Interest | Suicide after cyberbullying | 15 | Male | January 5, 2011 |

| Remembering Or—In Memory of Or Michaelovich | 40.3K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | August 12, 2014 |

| In the Memory of Zinedine Salman | 5.5K | Community | Officer/policeman, killed in line of duty | 30 | Male | November 19, 2014 |

| Eli and Nurit Harari H.Y.D. (God will avenge their blood) | 3.4K | Community | A drive-by shooting on the road in Samaria | 30 | Female and male spouse | October 1, 2015 |

| In Memory of Cpl. Hodaya Cohen RIP | 12K | Community | Terror attack in Jerusalem | 19 | Female | February 3, 2016 |

| Avi Baruch—we will remember you forever | 26.5K | Community | Shooting terror attack in Tel Aviv | 26 | Male | January 4, 2016 |

| In the way of Gal—In Memory of 1SG Gal Levi RIP | 4K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 19, 2015 |

| In Memory of Beni Ram RIP | 18K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of Naveh Goldstein RIP | 3.8K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 23 | Male | November 22, 2014 |

| A Page In Memory of Ofek Noy H.Y.D (God will avenge his blood) | 8.1K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 22, 2014 |

| Always remembering Yoni Kedem H.Y.D. (God will avenge his blood) | 13K | Public Figure | Yasam officer (Police Special Patrol Unit), died in line of duty | 29 | Male | October 16, 2016 |

| Sapira Sandler RIP—the official Page | 3.2K | Interest | Murder | 37 | Female | June 3, 2012 |

| Remembering Kate Tomer | 1.2K | Public Figure | 2006 Lebanon War | 26 | Female | July 7, 2012 |

| Page name . | Followers’ count . | Category . | Cause of death . | Age . | Gender . | Date of Page creation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Memory of Yoram Samson RIP | 19K | Community | Under investigation—accident, suicide, or murder | 23 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of ACOP Eytan Bar | 7.7K | Government official | Suicide | 55 | Male | July 5, 2015 |

| In Memory of Shelly David RIP | 10.5K | Community | Murder | 20 | Female | May 2, 2014 |

| Remembering Talya Nadav with a smile | 4K | Community | Car accident | 21 | Female | May 24, 2015 |

| Osnat Shemesh—The sun will never set | 10.6K | Community | Bus crash in Nepal | 22 | Female | November 6, 2014 |

| David Mishori RIP | 40.3K | Interest | Suicide after cyberbullying | 15 | Male | January 5, 2011 |

| Remembering Or—In Memory of Or Michaelovich | 40.3K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | August 12, 2014 |

| In the Memory of Zinedine Salman | 5.5K | Community | Officer/policeman, killed in line of duty | 30 | Male | November 19, 2014 |

| Eli and Nurit Harari H.Y.D. (God will avenge their blood) | 3.4K | Community | A drive-by shooting on the road in Samaria | 30 | Female and male spouse | October 1, 2015 |

| In Memory of Cpl. Hodaya Cohen RIP | 12K | Community | Terror attack in Jerusalem | 19 | Female | February 3, 2016 |

| Avi Baruch—we will remember you forever | 26.5K | Community | Shooting terror attack in Tel Aviv | 26 | Male | January 4, 2016 |

| In the way of Gal—In Memory of 1SG Gal Levi RIP | 4K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 19, 2015 |

| In Memory of Beni Ram RIP | 18K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of Naveh Goldstein RIP | 3.8K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 23 | Male | November 22, 2014 |

| A Page In Memory of Ofek Noy H.Y.D (God will avenge his blood) | 8.1K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 22, 2014 |

| Always remembering Yoni Kedem H.Y.D. (God will avenge his blood) | 13K | Public Figure | Yasam officer (Police Special Patrol Unit), died in line of duty | 29 | Male | October 16, 2016 |

| Sapira Sandler RIP—the official Page | 3.2K | Interest | Murder | 37 | Female | June 3, 2012 |

| Remembering Kate Tomer | 1.2K | Public Figure | 2006 Lebanon War | 26 | Female | July 7, 2012 |

| Page name . | Followers’ count . | Category . | Cause of death . | Age . | Gender . | Date of Page creation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Memory of Yoram Samson RIP | 19K | Community | Under investigation—accident, suicide, or murder | 23 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of ACOP Eytan Bar | 7.7K | Government official | Suicide | 55 | Male | July 5, 2015 |

| In Memory of Shelly David RIP | 10.5K | Community | Murder | 20 | Female | May 2, 2014 |

| Remembering Talya Nadav with a smile | 4K | Community | Car accident | 21 | Female | May 24, 2015 |

| Osnat Shemesh—The sun will never set | 10.6K | Community | Bus crash in Nepal | 22 | Female | November 6, 2014 |

| David Mishori RIP | 40.3K | Interest | Suicide after cyberbullying | 15 | Male | January 5, 2011 |

| Remembering Or—In Memory of Or Michaelovich | 40.3K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | August 12, 2014 |

| In the Memory of Zinedine Salman | 5.5K | Community | Officer/policeman, killed in line of duty | 30 | Male | November 19, 2014 |

| Eli and Nurit Harari H.Y.D. (God will avenge their blood) | 3.4K | Community | A drive-by shooting on the road in Samaria | 30 | Female and male spouse | October 1, 2015 |

| In Memory of Cpl. Hodaya Cohen RIP | 12K | Community | Terror attack in Jerusalem | 19 | Female | February 3, 2016 |

| Avi Baruch—we will remember you forever | 26.5K | Community | Shooting terror attack in Tel Aviv | 26 | Male | January 4, 2016 |

| In the way of Gal—In Memory of 1SG Gal Levi RIP | 4K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 19, 2015 |

| In Memory of Beni Ram RIP | 18K | Interest | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 21 | Male | July 20, 2014 |

| In Memory of Naveh Goldstein RIP | 3.8K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 23 | Male | November 22, 2014 |

| A Page In Memory of Ofek Noy H.Y.D (God will avenge his blood) | 8.1K | Public Figure | The 2014 Gaza War—Operation Protective Edge | 22 | Male | July 22, 2014 |

| Always remembering Yoni Kedem H.Y.D. (God will avenge his blood) | 13K | Public Figure | Yasam officer (Police Special Patrol Unit), died in line of duty | 29 | Male | October 16, 2016 |

| Sapira Sandler RIP—the official Page | 3.2K | Interest | Murder | 37 | Female | June 3, 2012 |

| Remembering Kate Tomer | 1.2K | Public Figure | 2006 Lebanon War | 26 | Female | July 7, 2012 |

| Age group . | Teen/pre-military (15–18) . | Military age (18–21) . | Twenties . | Thirties . | Older (40–55) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 1 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| Age group . | Teen/pre-military (15–18) . | Military age (18–21) . | Twenties . | Thirties . | Older (40–55) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 1 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| Age group . | Teen/pre-military (15–18) . | Military age (18–21) . | Twenties . | Thirties . | Older (40–55) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 1 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| Age group . | Teen/pre-military (15–18) . | Military age (18–21) . | Twenties . | Thirties . | Older (40–55) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 1 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

Data collection procedures employed Facebook’s search bar (Marwick & Ellison, 2012; Navon & Noy, 2021). We looked for keywords and phrases related to death and memorialization while using Facebook’s filter to specifically reach Pages (and not Groups or Profiles). Because the display of Facebook’s search results is managed by unclear criteria (alphabetical order, date of creation, followers count, etc., see Kern et al., 2013; Kern & Gil-Egui, 2017; Navon & Noy, 2021), we conducted multiple searches, which led us to different lists of Pages. To further offset Facebook’s unknown algorithmic preferences, we did not always sample the Pages from the top of the result list.

After collecting the data, we selected Pages for analysis based on the “intensity sampling” method. Intensity sampling focuses on the relevance of specific cases, their expected contribution to the research, and the extent to which they offer insights into our field of research (Suri, 2011). In order to strengthen the data’s heterogeneity, we selected diverse cases in terms of age, gender, cause of death, socio-cultural background, etc.

As indicated earlier, Pages are visible and available to anyone on Facebook, which made the work of accessing all the contents, posts, and comments on each Page relatively easy. Since we are particularly interested in the admins’ roles and communicative practices, our analysis focuses on posts and not on comments. Still, the comments provided complementary material that enabled a better understanding of the larger picture, including the dynamics among users and between the users and the admins.

Analysis

Between June 2018 and March 2021, following the data collection phase, we conducted ethnographic fieldwork based on the principles of digital ethnography (Varis, 2016). Siding with Varis, we see ethnography not primarily as a data collection practice and not so much as a set of methods and techniques, but as an approach that “is methodologically flexible and adaptive: it does not confine itself to following specific procedures, but rather remains open to issues arising from the field” (Varis, 2016, p. 61). As such, we do not employ a prestructured qualitative analysis procedure (such as content analysis), but address discursive concepts such as positioning and participatory dynamics (Giaxoglou, 2015; Harré, 2015; Navon & Noy, 2021). Following Romakkaniemi et al. (2021), we link the frames of positioning and social capital, taking positioning as both a theoretical and methodological framework (p. 5). We identified and analyzed positioning levels (for instance, positioning of the deceased, of the Page, of the admins, and of the followers) and positioning strategies, which we refer to as techno-discursive practices (from choosing the most beneficial Page category to describing the deceased and the death story in a collective/heroic manner). We were sensitive to relations between actors as established through positioning, keeping in mind that the “way individuals are positioned in social structure can be an asset in itself, and social capital is conceptualized as that asset” (Basu et al., 2017, p. 782). Examining positions and positioning, we highlighted different roles, different acts of participation, and levels of engagement and commitment, which together amount to participatory dynamics between the network members (Navon & Noy, 2021). We applied these discursive concepts more closely to several dozen posts from each Page, from which the examples below are taken.

In terms of research ethics, we now turn to address the processes of accessing, analyzing, and representing data from these memorial Pages. In a scoping review of 40 empirical papers, Myles et al. (2019) aimed to situate ethics in online mourning research. They suggest that “terrain accessibility constitutes a determining factor” (p. 293) in ethical decision-making, including data anonymization. They further refer to the difference between a Facebook Page and a Facebook Profile in terms of “the nature of the online setting” (p. 292). Yet, they emphasize that ethical decisions should not rely on technological arguments and affordances, but rather on an actual ethical reflection. In line with Markham (2015), they invite researchers to think contextually about ethics and conclude that ethical judgments could only be made in context. In the context of the current study, we believe that the activity on the memorial Pages in our sample possesses a distinct public quality. Nevertheless, to ensure anonymity, we changed the names of the deceased/the memorial Pages, and since we translated all the quotes from Hebrew, they could not be located via search.

Varis (2016) highlights the difference between early research of technologically mediated communication that centered around “things” or “texts” (collected randomly, detached from their social context) and later research that examined “actions” and situated practices. This shift builds on a new understanding of discourse as a socially contextualized activity. In this perspective, context and contextualization are critical issues that “should be investigated rather than assumed” (p. 57).

Varis suggests two contextual layers that digital ethnographies of communication need to investigate. The first is media affordances and the second is online–offline dynamics. We implemented these two layers as part of our analysis. As for the first layer, we pursued an ethnography of affordances, identifying and investigating different affordances that admins use when creating and maintaining a Page, and how features such as Likes, Shares, and Following shape discourse and dynamics on the Page. In line with Klastrup’s (2015) and Kern and Gil-Egui’s (2017) study of Facebook memorial Pages, we also examined the About section of each Page and analyzed the textual data therein.

The About section serves as the Page’s visiting card. It displays its basic information, in part provided by Facebook and in part by the admins. This includes the current number of people who like and follow the Page, its category, contact info, and a short introductory text. Up to May 2020, during our data mining stage, the About section also included the Page creation date and, in most cases, a “Team Members” title which shows the admins. In the updated version, this information was removed. A new section called “Page Transparency” was added “in an effort to increase accountability and transparency of Pages” (Facebook Help Center, n.d.). Yet, the information provided in this new section is actually more limited when compared to the previous version. A “Page History” title presents the creation date; however, a new title “People Who Manage This Page” does not reveal names and Profiles as it used to in the past, but rather only the primary country location of the admins. This update reinforces previous observations about the vagueness and anonymity of Pages’ administrators (Grömping & Sinpeng, 2018; Kern et al., 2013; Kern & Gil-Egui, 2017; Poell et al., 2016), and puts into question Facebook’s declared efforts to increase transparency. Specifically examining memorial Pages, Marwick and Ellison (2012) likewise observed the difficulty “to ascertain who created the page and their motivations for doing so” (p. 388). In the current study, we try to answer these questions based on the Team Members data we collected before the Facebook update, a textual analysis of the About texts, and the ethnography we conducted.

As for the second layer, online–offline dynamics indeed turned out to be an important part of our analysis. The memorial Pages in our sample are all created in memory of actual people and the life they lived offline or their offline death story, as opposed to studies of memorial Pages that included Pages dedicated to fictional characters, places, or things (Forman et al., 2012; Kern et al., 2013). Moreover, the activity on these memorial Pages involves production, promotion, and documentation of a rich variety of offline events, as will be discussed shortly in the findings section. Below we discuss the Pages’ names, their categories, About texts, admins, and followers’ count along with the analysis of admins-followers interaction and the activity on the Pages.

Findings and discussion

Page name

The first finding we discuss corresponds with the first step of creating a Page: supplying the Page name. Typically (72% of the cases), the Page name consists of two verbal elements. The first element concerns one of the following phrases: “In memory of …” or “Remembering …,” which is formative because it designates the meaning of the Page as a memorial site. The second element is the deceased’s full name, which appears in all the cases. Supplying the deceased’s full name contributes to a more formal and respectful tone. It accords well with cases in which the dead have served in the military or in a police unit, where their rank appears next to their name as part of the Page title (“In memory of ACOP Eytan Bar,” or “In memory of Cpl. Hodaya Cohen”). In this vein, several titles include an English translation or the ending “the official Page of …,” serving to establish a sense of formality, authority, and recognition of the Page and of the deceased. Supplying the deceased’s full name may also suggest that Page creators do not expect or assume that all visitors know the deceased personally or beforehand. One way or another, a norm seems to be emerging in regard to naming memorial Pages, which is based on the evocation of one of the two phrases together with the deceased’s full name.

Page category: community, public figure, interest

Right below the Page name, the Page category appears in grey and in smaller letters. A Page category “describes what type of business, organization or topic the Page represents” (Facebook help text). When creating a Page, Facebook affordances allow users to type freely in the Page category text box while receiving “help” from Facebook in the shape of prompting or introducing to the user existing categories according to the letters she types. These potential categories may seem like helpful suggestions, but in fact, the user must choose one of these pre-existing options. In other words, defining a category is a necessary step in creating a Page on Facebook, which can be done only according to a pregiven list that the platform provides.

The list of available categories that Facebook offers (as of July 2021) comprises over 1,500 possibilities, which include, for example, 12 types of Tour Agencies, 15 subcategories of Pet Services, 28 different types of Chinese Restaurants, and a similar number of Beverage shops (from Sake Bar to Tiki Bar). However, none of the categories or subcategories offered in the detailed list relates to memorialization, nor to synonyms or related terms (commemoration, remembrance, death, dying, mourning, grief, etc.). This raises interesting questions: How carefully does Facebook select, form, and shape Pages’ categories and uses? How do users act within this framework of affordances? And more practically, which categories do users employ in memorial Pages when such elementary categories are missing altogether?

Our findings point to three main categories of memorial Pages: Community (44.4%), PublicFigure (27.7%), and Interest (22.2%). Based on Facebook’s official list, the Public Figure category refers to an actor, author, scientist, etc., and the Interest category includes Sports, Visual Arts, and the like. In the context of memorial Pages, however, the meaning of these categories is negotiated. They do not reflect the meaning Facebook provides, but instead the interpretations that users/admins ascribe in line with their goals: to engage interest in the Page, to create a large community that recognizes and remembers the deceased, and to turn her/him into a public figure. This finding demonstrates an interactional view of affordances as a relationship and negotiation between the interface and the user, rather than merely a property, or a feature, of the interface itself—an “entanglement of policy and practice,” in the words of Arnold et al. (2018, p. 52). Users take the freedom to interpret Facebook categories creatively in order to contend with restrictions put forth by the platform. They might not have absolute freedom to choose the Page category, but they enjoy the freedom, which they exercise, to choose how to interpret and use it.

This finding also reveals an emerging norm concerning the socially accepted way of naming and categorizing memorial Pages. This norm hints at admins’ underlying motivations for creating and maintaining a memorial Page (more on this below).

Admins’ concealed identity

Four cases in our sample (22%) appeared with users (linked Profiles) as Team Members. In three of these four cases, the surname of the admin user was identical to that of the deceased, yet the specific kinship was unspecified. This relation has not been revealed in the About text as well, but a review of the posts along the Pages tells us that two are mothers of the deceased, one is a sister, and one is a cousin (hence the different surname). In two other cases (11%), the introductory text in the About section refers to the Page admins, though in an unspecified way: “The Page is moderated by the loving family,” and “The Page is moderated by friends from Na’ariah [city] and by Nurit’s brothers.” Finally, in three additional cases (16.6%), we were able to deduce who runs the Page by looking at the posts over time, as the information was not provided in the About section (neither as Team Members nor in the introductory text). In one case, the admin is the deceased’s daughter who often signs posts as “daddy’s girl”; in a second case, it is the sister who frequently mentions her name, uploads photos of herself, and shares posts from her personal Profile on the Page. In the third case, family pictures appear frequently, and most of the posts end with the designation “the family,” but no further information is provided about the specific admins. Overall, in all the nine cases we detailed above (50% of our sample), the admins are self-identified as relatives of the deceased, and in the rest of the cases (50%), it is unclear who created or manages the Page. In other words, in most cases it is difficult to determine who the admins are (again, cf. Marwick and Ellison, 2012).

Admins’ motivations and collective discursive positioning of the deceased

In more than half of the cases (61%), admins describe in the About section the reason(s) for which they have created the Page. The accounts they supply share similar motifs: “We opened this Page to keep the spirit of … alive,” “This Page was created for the memory of …,” and “This Page is in his memory and to inspire his legacy.” In other words, the goal of the Page, as stated by the admins, is to have the deceased remembered publicly. More precisely, it is to make the deceased remembered and recognized by as many people as possible, beyond the circles of relatives and acquaintances who knew her when she was alive. In most of the cases (83%), admins use the About text as a space to write about the deceased and provide basic information that should presumably be known to acquaintances. For example, age at death, date and cause of death, a list of family members who are left behind, or a short biography. In line with the formal register, these brief biographies are often written in an informative and factual manner. Consider the following example:

Beni was born on the date of 26/6/1993 in Ramat Yishai … In his adult life he played water polo … on Israel’s national team … While he could have served [in the army] in a non-combative position as an “Outstanding Athlete,” in March 2012 he chose to enlist into the Combat Engineering Corps. Beni completed basic training with distinction … On the afternoon of 19/7/14, Beni was fatally wounded from a missile … Beni was buried on 20/7/2014 in the Kiryat Tivon military cemetery. 3500 people attended his funeral. Beni left behind parents, three brothers, maternal and paternal grandparents, uncles, and aunts. A large family in pain and in tears. [About text, the Page In Memory of Beni Ram RIP, n.d.]

Such texts supply a brief overview of the deceased’s life story, highlighting his exemplary military service and heroic death. The death story is charged with a deeper meaning relating to honor, sacrifice, patriotism, and recognition, that aims at transforming it from a personal death story to one that is collective and anchored in the public sphere. Hence the detailing of the (large) number of people who attended the funeral. Stressing the deceased’s contribution to the state or society adds both moral and collective values to the act of remembrance, to those publicly and collectively engaging it, and thereby also to the memorial Page itself. This finding echoes Harju’s (2015) observation of “a stance of moral superiority” (p. 130) that users construct in relation to public mourning of a celebrity on YouTube (Steve Jobs). The question at heart is a moral and sociocultural one, namely who is worthy of public remembrance?

According to Harré (2015), moral questions are integral to discursive positioning. The positioning theory claims that every thought, expression, and social action in and among groups “take place within shared systems of belief about moral standards,” and about the distribution of roles, rights, and duties (p. 266). Similarly, Giaxoglou (2015) describes affective positioning as “semiotic and discursive practices whereby selves are located as participants … producing one another in terms of roles.” (p. 56). Our findings point at heroic and sacrificial discursive positioning in all the cases in which the deceased served in the military or the police. For example: “Her death saved many lives,” and “…Taking the shot in his own body, Yoni prevented multiple deaths.” These and similar texts portray the ultimate sacrifice paid by the deceased, evoking a sense of patriotic gratitude (Noy, 2015).

In one case, in a Page dedicated to the memory of Shlomo Levi, the About text opens with this brief introduction: “Gal Levi—a son, brother, friend, worrier.” Here the discursive positioning reflects a scale that ranges from the personal, through the familial (first “son,” then “brother”), to the social and the institutional. In another case, even though the deceased’s cause of death was suicide and he did not fall in the line of duty, his rank plays a salient role. On the About it says: “This Page intends to commemorate the legacy of the officer, the policeman, and the beloved person, Major General Eytan Bar.” The admin of the Page is self-identified as the deceased’s daughter, who regularly signs her posts with the words “daddy’s girl,” yet the focus lies with his public role and contribution. The goal is to form his memory as a respectable individual who has served the country and the society well.

Collective and often heroic discursive positioning also appears when the deceased was not a soldier nor held a formal institutional role. In these cases as well, admins highlight the social importance of the deceased or the death story and the collective values it embodies. Such is the case in the Page in memory of Talya Nadav. Talya died in a car accident abroad involving negligent DUI by two Israelis who avoided prosecution. The admin stresses the relevance of the tragic death story to the general public.

We need your support: after a year and ten months they [the perpetrators] are still walking free … They deserted Talya who died and fled Mexico. We begin a struggle to bring them to justice. Enter the link and donate for “Justice for Talya Nadav.” For us. For everyone. Because we all travel abroad. Us, our children, our friends. We might all find ourselves in a similar situation. [The Page Remembering Talya Nadav with a smile, March 9, 2017]

This example demonstrates how the admin discursively positions the deceased and the death story as a matter of collective interest. She builds on the shared value of justice to mobilize social engagement and support in the form of crowdfunding. The deceased becomes a symbol, yet this is achieved not by appealing to themes associated with national sacrifice and gratitude, as in the case of the soldiers, but by appealing to a sense of social responsibility. These dynamics resonate with Walter’s (2015) observation, that in “contemporary culture’s celebration of vulnerability … victims are now as or more likely to be commemorated as heroes” (p. 13).

Furthermore, even when death is not framed in terms of victimhood, admins still position the deceased as a valuable collective symbol. They do so by portraying her special virtues and unique character. In the case of Osnat Shemesh, a backpacker who died in a weather related bus crash in Nepal, the admins state: “We’ve chosen to take ‘the life according to Osnat’ and turn it into legacy, into a will.” Here, too, the deceased is elevated, as her life is presented in hindsight, as embodying shared values with which the audience can identify. Themes concerning national sacrifice and collective gratitude are altogether absent, yet the deceased is framed as a collective symbol. Admins supply quotes by the deceased, which they frame as a motto or a legacy (a practice employed in the mourning of celebrities. See Harju, 2015, p. 137), and share stories about her life and highlight her virtues. These acts of discursive positioning serve to supply an account for the reason that that specific person is worth remembering.

The page followers’ count: admins’ efforts to increase the network

If someone is worth remembering, her/his memorial Page should be worth following. The followers count shows how many users are following a Page. In quantitative terms, this index measures circulation and exposure, i.e., the size of the network (Ellison & Vitak, 2015). In qualitative terms, the followers’ index helps assess the Page’s popularity and social impact, and the social capital that Page admins have come to possess.

The average number of followers on the Pages we sampled is 13K, ranging between 1.2K to 40.3K. Explicit efforts to gain followers, Likes, and Shares appear in all 18 cases, pursued through repeated and explicit requests by the admins (“Please share the Page with your friends. Thank you”). In one case, admin offers a small token in the shape of bracelets to new followers:

Enter the “Osnat’s Butterflies” Facebook Page, Like the Page, and you can get free bracelets … [We] warmly ask that you “Like” the Page “Osnat’s Butterflies,” and request that the bracelets will be sent to you. [The Page Osnat Shemesh – The sun will never set, July 11, 2015]

The butterfly bracelets are part of a social initiative propelled by this Page’s admins for promoting good deeds and giving, in the spirit of “Pay it Forward.” This initiative was established in memory of Osnat Shemesh, the backpacker who died in Nepal, and had a butterfly tattoo on her shoulder. Osnat’s Butterflies Page has over 33K followers, and the social initiative it promotes has reached over 40 countries worldwide. The goal of the Page is to increase public awareness and support for the project by documenting and posting butterflies’ paintings and bracelets around the world, alongside moving stories about Osnat Shemesh (the deceased). In this way, the Page accomplishes the goals of memorial Pages, as implied in the categories we discussed above: building a community, engaging interest, and turning the deceased into a public figure.

The idea of publicizing the deceased is exemplified quite clearly also in the following post, taken from a Page in the memory of Police Assistant Commissioner Eytan Bar. As indicated earlier, Bar ended his own life in the wake of an investigation he was under. The admin of the Page is his daughter (“daddy’s girl”):

You’re all invited to Like and Share the Page in memory of our father, so no one will forget this angel who wholeheartedly gave his life to the country. [The Page In Memory of ACOP Eytan Bar, July 26, 2015]

This short message performs the transition from a personal loss (“our father”) to one that is collective and public (“gave his life to the country”). Such texts hint at the perceived connection that users make between online participatory acts, such as Follow, Like, and Share, and participatory acts of a cognitive or emotive nature like memory, recognition, and esteem. The admin uses the conjunction word “so” (“so no one will forget”) to form a causal connection between Like/Share and a public memory, between visible online engagement and cognitive or emotive implications.

Offline page activity: initiatives and events

The Page Likes that we examined offer only a “glimpse” (Bernstein et al., 2013, p. 21) of how admins can evaluate the activity of their audience. In the case of Facebook memorial Pages, the activity extends beyond the online sphere and involves production, promotion, and documentation (uploading and posting pictures) of offline initiatives and events. The initiatives vary, reflecting the sociocultural differences found in our sample, which, in turn, reflect pre-existing memorial practices in Israeli society. Some cases have a more spiritual or religious orientation—inauguration of a Torah scroll and other Jewish rituals; in other cases, there are sporting events—racings, soccer tournaments, mass Zumba workouts; and yet, others take the shape of intellectual or educational activities—talks at schools, Mind Sports Olympiad, etc. We can therefore see that, in most cases, the admins promote multiple events and initiatives throughout the year, which make the Page active constantly, rather than only around a single, annual memorial event. The frequent activity on the Page serves to maintain an ongoing interaction with the network and to establish the Page as an appealing and vibrant site.

Despite the differences in terms of content, we found several similarities in the ways admins communicate and promote these initiatives. First, the format: In 89% of the cases, event announcements (information about an event) take the shape of a photo—a professionally designed flyer—and not a textual post. The flyers are visually stylized and convey an impression of a formal invitation. The second similarity concerns addressivity, or who the posts address. These invitation posts are directed at the general public, calling for as many people as possible to join the community-turned-network and partake in its activities. Third, in most of these posts, similar keywords are used, evoking themes that concern respect, recognition, and togetherness. Consider these examples:

Join [pl.] us for an inauguration of a Torah scroll

In honor and in loving memory of the combatant Cpl. Hodaya Cohen

… The general public is welcome to pay respect. [The Page In Memory of Cpl. Hodaya Cohen RIP, March 27, 2017]

We invite you all to come, watch and participate in the heritage of our father. It is important for us that a large crowd will show up, so that it will be respectable. The tournament will take place in Modi’in, and silicone bracelets will be sold for 10 shekels [3 USD] with the inscription “Love thy friend as thyself – in the spirit of Eytan Bar’s path.” We will donate the money to the same places that our father used to support. We are looking forward to seeing you. Spread the word! [The Page In Memory of ACOP Eytan Bar, June 12, 2017]

Both examples include the words “honor” and “respect” (which in Hebrew are the same word, kavod). The notion of respect is significant, and the crowd plays an important role in its amassment. Indeed, the presence of a large crowd is the very mechanism through which respect and honor are generated and publicly assessed. Hence the address is directed at “the general public” and “you all.” Moreover, the second example ends with the directive “Spread the word!,” explicitly seeking to reach beyond the Page followers. The Admin makes use of the network (followers) alongside the platform affordances in order to reach as many people as possible, to generate large attendance, and to amass respect.

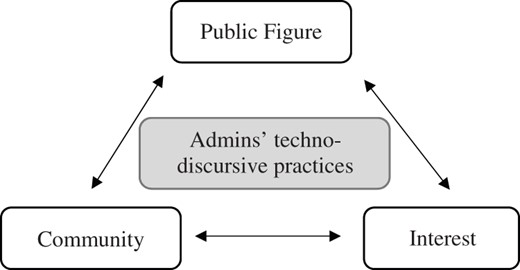

As part of the production of multiple memorial events and initiatives, admins often address the followers with various requests for resources and participatory actions. These actions range from physical attendance, through volunteering and contributing one’s skills and knowledge (video editing or teaching Zumba), to purchasing memorial merchandise and donating money. Requests for resources include, as we can see, economic capital (Bourdieu, 1986), but also practical support, which is appreciated as a form of social capital resources (Xu et al., 2021). The extensive memorial activity and the involvement or harnessing of wide crowds (representing “the public”) in its production, fulfill the three goals of memorial Pages we detailed earlier: Community, Interest, and Public Figure.

These three common categories of memorial Pages can be seen as reflecting three aspects or dimensions of the same process. In this process, users create and maintain memorial Pages, which come to serve as mechanisms for the accumulation of social capital resources. These categories are interrelated and represent different aspects or stages of the same process. This process entails the assumption that at stake here is a collective interest, which results in attempts at creating a community, and establishing the deceased as a public figure.In fact, turning the deceased into a public figure builds on the size of the community and the degree of its members’ engagement and interest.

The ongoing activity on memorial Pages, including the positioning of the deceased and the various online and offline events, are all put in the service of the same three goals or stages in this process: building a community (with high levels of involvement and commitment), engaging interest, and ultimately positioning the deceased as a matter of public interest, in other words, as a public figure worth remembering (Figure 1).

Memorial Pages’ categories as interrelated means in social capital processes.

Memorial merchandise: economic and social support

The second example above draws attention to another widespread practice we observe in our data, namely selling merchandise in memory of the deceased (in this case silicone bracelets). In 61% of the cases in our sample, this practice appears to be popular and in some cases, several types of merchandise are sold through the Page. The examples vary: T-shirts, baseball hats, bumper stickers, memorial candles, and recently also face masks (due to Covid-19). All the products are imprinted with the full name of the deceased alongside an image, a slogan, or a quote that is made to be associated with her/him. Wearing this memorial merchandise means carrying the deceased’s memory offline in an embodied fashion, continuing and honoring his legacy. As Harju (2015) puts it, apropos her discussion of celebrity commemoration on YouTube, “materiality anchors meanings” (p. 136).

This finding is significant because branded merchandise is generally associated with celebrities and not with ordinary people. Designing and selling merchandise in memory of an individual, therefore, convey a message that he/she was a famous person or should be famous posthumously. Furthermore, since nearly all sold merchandise are wearable, they promote offline public display of the deceased and enhance her status as a public figure. This closely relates to our earlier finding about the frequent employment of the Public Figure category and confirms our argument about the underlying motives and goals of admins of memorial Pages.

The admins use the memorial Page to promote, distribute, and sell this merchandise, and in line with the moral discursive positioning on the Page, they add a moral value to those products and to the act of buying and using them. Consider these two examples: “Wearing the bracelet commits the wearer to maintain the values you [the deceased] represents and in this way to become a better person,” and “10 Shekels for your contribution and involvement in the Observatory project in memory of Ofek. So friends, share and get yourself a new bracelet for a worthy cause.”2

The purchase of memorial merchandise emerges as a value laden moral action because (1) the deceased is consistently portrayed as a special person whose story carries social meaning and significance and bears moral value; (2) the money that is collected is directed to worthy and charitable causes, such as donations; and (3) participatory actions such as buying memorial merchandise supports the (often bereaved) admins. The support that admins receive is twofold: it is financial (economic capital, Bourdieu, 1986), but also social and emotional (social capital, Williams, 2006). The action of purchasing a memorial merchandise reflects both interest and involvement, and enhances the sense of recognition with regards to the social significance of the deceased. The admins are well aware of these meanings and in response, express their gratitude readily and frequently as we show below.

Expressing gratitude: from followers to partners

Alongside the multiple repeated requests and invitations that Page admins direct at the Page followers, they also make sure to thank them devotedly. In doing so, the admins’ tone is rather informal, personal, friendly, and enthused. They routinely express gratitude and show their appreciation to followers and their engagement. Every action counts. From Like and Share, through money donations, to physically attending events—admins show that no activity goes unnoticed. They highlight the importance of these actions as not merely helpful, but truly vital for the memorial Page and its moral goal. Followers thus become an integral part of the Page and its activity, or in other words, they are repositioned as partners. Indeed, sometimes admins note this explicitly: “We are grateful for having such partners as yourselves.”

At stake here is a significant “status promotion” for the followers, which is pursued vis-à-vis Facebook’s affordances and hierarchical terminology: Admins, who manage, approve, curate, edit and produce content, and followers, who consume it. By symbolically “upgrading” the followers to the status of partners, admins imbue the followers with a sense of importance and enhance their commitment and engagement with the Page. In this way, they encourage the followers to contribute more: more Likes, content, resources, and engagement.

The following example nicely captures this circle of encouragement-engagement here in relation to the inauguration of a Torah book.

Wow, how exciting…. Thanks to you we achieved the goal!!! … with every passing day, the hug we received grew greater and greater. Thanks to you… to your shares… to your devotion … more than 100,000 shekels were raised in the last couple of days for the commemoration of Ofek!! [The Page In the Memory of Ofek Noy H.Y.D, September 8, 2016]

Communication here seems spontaneous and informal, and while the accomplishment is framed as mutually achieved (“we achieved the goal!!!”), gratitude is clearly expressed and extended to the followers (“Thanks to you” and “to your shares”). Followers’ engagement is described as a “hug,” a nonverbal act that indexes affection, support, and closeness. Thus, admins discursively position the followers, who are otherwise strangers, as helpful in extending love and support. This finding resonates with Stage and Hougaard’s (2018) discussion about “caring crowds” (p. 79), in which love and care are not only expressed through words but also through “material practices” (p. 94). In the cases they observe—two public Facebook Groups that were created for two children diagnosed with cancer—crowdfunding was a dominant practice that was motivated and energized by sharing the personal stories of illness and suffering, alongside gratitude expressions by the parents who run these Groups.

In the following example, the mother of Osnat Shemesh (mentioned earlier) nicely illustrates how to direct attention to the followers.

When you experience the most excruciating pain possible, you hold on to any bit of light, like a wounded animal. It seems like this is the only way to survive. In the last couple of months, family and friends have completely embraced us, and I will forever owe them my life and my sanity. I want now to talk about the people we don’t know; about bits of light that radiate from people who never knew us or Osnat. These people, who send us comforting messages, strangers who took time off their everyday routine … to all these beautiful souls … we wish to say thank you. Thanks for seeing us. Thanks for taking time off for us. Thanks for helping us regain our faith in goodness. [The Page Osnat Shemesh—The sun will never set, December 25, 2014]

Emphasizing the pain this admin is experiencing (“most excruciating pain possible”), enhances the moral value of the followers’ benevolent participatory actions. The admin, a bereaved mother, mentions and thanks family and friends,then directs special attention to other people. She pursues this by the meta-discursive statement “I want now to talk about…,” through which she signals a thematic shift to what will be the focus of her message, namely to those who deserve the utmost gratitude. These are “strangers” — users with whom she is not familiar, who showed showed interest and “took time off,” and who served as an audience (“Thanks for seeing us”) and a network. The admin describes the visitors and the followers of the Page as radiating “bits of light” and as “beautiful souls” who help restore faith in goodness.

Posts of this type (re)confirm the moral value that engaging the Page carries, framing it as a socially valued action. This is a result of the social solidarity and support that followers direct at the admins, often bereaved users in pain, and of the fact that memorialization is generally held as a socio-moral project (Noy, 2015, p. 39) — more so when the deceased is consistently portrayed as a hero, a special person, a respectable public figure worth remembering.

Such expressions point at how admins acknowledge having received emotional support from their network of followers. Recall that Putnam (2000) and Williams (2006) associated emotional support and mobilization of solidarity to bonding social capital, that is, to interactions that are typical of strong ties and closer relationships. Interestingly, our findings suggest that such resources may also be obtained through what we can call “bridging relations” and interactions with a broad network of mostly strangers. Admins explicitly and repeatedly link emotional support to such parameters as engagement with the Page, the economic capital gained through the network, and the practical support followers provide.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored Facebook Pages created in memory of ordinary people with the aim of raising social awareness and public remembrance of their death. We offered a new perspective on these memorial Pages and suggested viewing them through the scope of the social capital approach. In line with existing literature (Ellison & Vitak, 2015), our findings demonstrate that the most significant factors of social capital processes are the size and composition of one’s network and the patterns of interaction.

We identified different communicative practices that admins pursue in the aim of reaching an audience, increasing the size of their network (i.e., followers count), and enhancing its activity and engagement. In addition, we analyzed how admins interact with their network—a multi-layered communication that serves the multiple functions they seek to accomplish. On the one hand, admins use a formal register, and the notion of respect is salient as they try to establish a sense of formality, authority, and recognition towards the deceased and the Page. On the other hand, they use a highly personal, enthused, and emotional register partly because of the engaging effect of affective performances, and partly because of the affect-laden quality of digital mourning practices (Giaxoglou & Döveling, 2018). When a user performs an increased emotional sharing, it activates reactions of the networked audience in the shape of an exchange of emotional and support resources (Baym, 2010, in Giaxoglou et al., 2017), which have been shown to reinforce tie strength (Xu et al., 2021). In a discussion on networked emotions and sharing loss online (Special Issue of Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 2017), Giaxoglou et al. (2017) observe the “increasing mobilization of emotion as a commodity” (p. 7), and Sabra (2017) further notes that the potential for economic and emotional capitalization is integrated into the Facebook platform (p. 31).

Our findings flesh out these observations by showing how admins carefully and strategically select where and when to use a formal and factual register (e.g., the About section, biographical and informative posts), and when to use a more personal and friendly emotional tone (e.g., posts extending gratitude and appreciation that yield an encouragement-engagement circle).

The expected engagement, and with it requests for resources that admins post, range from online participatory acts to purchasing memorial merchandise, donating money, physically attending events, contributing one’s skills to the production of initiatives, and so on. The accumulation of resources through the Page is a social capital process par excellence, a process in which ordinary users become admins and create their own network, gradually expand it, and harness it by employing platform affordances to achieve their goals.

Network members are mostly strangers. While previous studies note that strangers are unwelcomed on Facebook memorial spaces (Rossetto et al., 2015; Walter, 2015), our study suggests that strangers are more than welcome and are deeply appreciated. In an effort to portray the deceased as a public figure and to establish a state of public remembrance, admins address the largest audience possible. Pages, as opposed to other Facebook subplatforms, afford this publicity and capitalization, which users acknowledge and take advantage of from the very early stages of creating and naming the Page. This complements studies that have examined social capital processes on Facebook and relationship maintenance behaviors of existing connections (i.e., Facebook friends). Here, we examined the creation, maintenance, and strengthening of new connections with strangers (i.e., Facebook followers), or parasocial relations, corroborating previous observations of memorial Pages, which “gather strangers rather than friends” (Klastrup, 2015, p. 147).

However, despite existing literature that links between strangers and “weak ties,” and bridging social capital outcomes (Putnam, 2000; Williams, 2006), in the case of the memorial Pages we studied, broad networks of followers that consist mostly of strangers, in fact, facilitate bonding social capital outcomes, such as solidarity and emotional support. Admins recognize this support and pursue a circle of encouragement-engagement that motivates participatory activities.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that future studies can address. First, due to the relatively small sample size, we could not draw conclusions relating to the connections or correlations between the cause of death and the activity or dynamics on the Page. Second, future studies may examine the collectivization of personal mourning and related social capital processes on other platforms with different affordances and dynamics (such as visual versus textual platforms). We believe that much of the transferability of these insights rests on platforms’ public quality or publicity. Finally, while we focused on memorial Pages, future research can explore social capital processes on Pages in different contexts and themes. Future research may also focus on social capital in relation to “special users,” such as admins (rather than ordinary users), who employ special affordances and pursue special practices.

Data Availability

The data underlying this study will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgment

We would like to wholeheartedly thank Sam Lehman-wilzig for reading and productively commenting on an earlier version of this paper. We are also deeply grateful to the JCMC's three anonymous Reviewers, Associate Editor Katy Pearce, and Editor Nicole Ellison for supplying helpful and encouraging comments, which made the review process constructive and enjoyable.

Notes

Our data collection process builds on the notion of “saturation,” or when the researchers estimate that new data have little more to offer, which is typical of qualitative research.

Memorial practices involving money donations and the purchasing of objects for charity purposes have existed in Israeli society and beyond before Facebook.