-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andreas Jungherr, Harald Schoen, Pascal Jürgens, The Mediation of Politics through Twitter: an Analysis of Messages posted during the Campaign for the German Federal Election 2013, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 21, Issue 1, 1 January 2016, Pages 50–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12143

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patterns found in digital trace data are increasingly used as evidence of social phenomena. Still, the role of digital services not as mirrors but instead as mediators of social reality has been neglected. We identify characteristics of this mediation process by analyzing Twitter messages referring to politics during the campaign for the German federal election 2013 and comparing the thus emerging image of political reality with established measurements of political reality. We focus on the relationship between temporal dynamics in politically relevant Twitter messages and crucial campaign events, comparing dominant topics in politically relevant tweets with topics prominent in surveys and in television news, and by comparing mention shares of political actors with their election results.

Digital services—such as Twitter, Facebook, and Google—have become common elements of political communication. Tweets, Facebook posts, and Google queries referring to politics accompany and react to political events, political coverage in traditional media, or campaign activities of political elites. Political events, controversies, campaign activities, and public sentiment thereby potentially leave traces in the logs of digital services. These digital trace data (Howison et al., 2011), and the image of political reality they offer, have become central to the performance, coverage, and analysis of politics (Chadwick 2013). Especially, the microblogging service Twitter has been on the forefront of this process, not necessarily due to its far from universal adoption but instead based on the comparatively easy access the service provides to its data. This has led politicians and journalists to use trends in Twitter messages as ad hoc polls promising real-time glimpses at public opinion (e.g. Anstead & O'Loughlin, 2015). Also, researchers increasingly turn to Twitter as a cheap substitute for traditional opinion polls or other more labor-intensive data collection efforts (e.g. Barberá, 2015; Tumasjan et al., 2010).

Thus, digital trace data are increasingly used as information source on political reality. They are thereby joining other media traditionally used in the public construction of social and political reality (e.g. Berger & Luckman, 1966; Couldry, 2012; Edelman, 1988). Both, sociology and communication research have shown that different media do not present a true reflection of social or political life but instead one mediated by various factors inherent to each specific media type. Identifying and assessing the potentially distorting influences of these mediating factors has for long been a highly productive research area in communication research (cf. Shoemaker & Reese, 2014). In the debate about public or scientific uses of digital trace data this perspective, as up until now, has largely been absent. This lack is all the more troubling, as here we appear to witness the reemergence of the mirror-hypothesis, expecting media to reflect political reality without distortion. While this thesis has become all but discredited in mass-communication research (cf. Shoemaker & Reese, 2014), it seems implicitly built into most arguments advocating the analysis of political phenomena based on data collected on digital services. However, it is important to realize that the reflection of politics in Twitter messages is not unfiltered but, like the reflection of politics in other media, the result of a mediation process.1 In order to leave traces in Twitter messages, political phenomena have to arouse the interest of Twitter users and be in line with users' political or personal motivations. Then, the reactions to political phenomena have to be encoded in 140 characters or less. Accordingly, the mediation process comprises at least three sets of factors: characteristics of phenomena in political reality at large, characteristics of Twitter users, and the technological design of the digital service.

Both developments—the increasing use of data provided by digital services to analyze the public's reaction to politics by political actors (e.g. Anstead & O'Loughlin, 2015; Kreiss 2014), and the growing use of digital trace data by researchers to draw inferences on political phenomena (e.g. Barberá, 2015; Tumasjan et al., 2010)—illustrate the increasing role of these data in the public construction of social and political reality. This underscores the relevance of understanding the mediation process of politics through digital services. In this analysis, we focus on the microblogging service Twitter and address the guiding question of whether reflections of political reality emerging from aggregates of Twitter messages provide a true mirror of political reality. More specifically, we examine where Twitter-based metrics concur or diverge from traditional metrics of political reality—such as surveys—and what mediating factors are likely to drive these differences. To examine this question, we analyze a data set of Twitter messages referring to politics posted during the campaign for the 2013 German federal election. We examine which political events drove spikes in the relative volume of Twitter messages referring to politics; we compare dominant topics of politically relevant messages with topics raised by respondents of a representative survey and a content analysis of important television news programs; finally, we test if mention shares of political actors on Twitter reflected their relative political importance as measured by their vote share.

The mediation of political reality through Twitter

The use of digital trace data in the analysis of social phenomena requires a close examination of the data generating processes of each service of interest. Only by understanding these data generating processes—the factors and processes influencing the mediation of reality through the usage patterns and technological design and affordances of a service—, scholars may assess how patterns found in digital trace data relate to social phenomena (cf. Howison et al., 2011; Jungherr, 2015). In general, this mediation process comprises several steps, resembling the macro–micro-macro linkage as discussed by Coleman (1990).

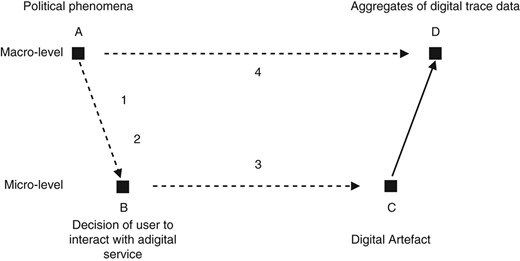

Figure 1 illustrates the process necessary for political or social phenomena to create identifiable traces in aggregates of digital trace data. Based on an underlying political phenomenon (A), a stimulus emerges which has to grab the attention of a Twitter user for her to consider referring to politics in a tweet (B). Then, users have to encode their initial responses to elements of political reality within the technological limitations of the microblogging service to create a digital artifact (C). The results of these individual-level decisions and behavior (i.e. tweets) can in turn be aggregated (D). Based on these aggregates, various metrics can be calculated (e.g. mention counts of political actors), potentially allowing inferences on the political phenomena giving rise to the data (4).

As the dashed lines in Figure 1 suggest, however, the relationship between tweets and political reality at large is filtered by various mediating steps, potentially introducing various biases, leading the picture of political reality emerging from aggregates of tweets to be blurred or skewed. Building on Shoemaker and Reese's (2014) classic hierarchy-of-influences model, we suggest three types of influences that may affect this mediation process. Some are based on characteristics of political reality (1), some on user characteristics (2), and some on the specific technological design of Twitter and respective usage conventions (3). Taking a closer look at them is useful in understanding the dynamics of this process and in forming conjectures on which parts of reality this process is likely to highlight and which it may downplay.

Influences of political reality

At the start of the mediation process, stimuli arise from political reality at large that might lead Twitter users to post messages referring to politics. Various types of stimuli might lead users to refer to politics in their messages. Users might react to personal experiences of politics—be they problems attributed to politics (e.g., unemployment), campaign contacts, participation in campaign events, or meetings with politicians. Alternatively, users might react to indirect experiences of politics—be they media events, like televised debates, election night coverage, or other high-profile political programs on television. Finally, they might also react to content on the web referring to politics, tweets posted by other users, or content prominently displayed on Twitter based on the service's algorithmic relevance-assessment.

Generally speaking, stimuli experienced by many Twitter users may lead more users to refer to them in more messages—and thus leading to detectable shifts in Twitter metrics—than stimuli shared by fewer users. Concerning direct experience, local stimuli are less likely to be represented in Twitter metrics than events or problems that affect people at many places. Also, most people experience politics indirectly through mass media coverage, leading political events and topics covered by mass media to have better chances to catch the attention of many users simultaneously than potentially important political events ignored by mass media. In effect, political events with high levels of coverage will be more likely reflected in pattern shifts in the aggregates of Twitter messages (see, e.g., Jungherr, 2015; Lin et al., 2014).

Influences based on individual characteristics of users

When looking at the aggregates of tweets referring to politics, it is easy to forget that each message—leaving aside those posted automatically—is based on the decision of an individual Twitter user to post a tweet mentioning political actors, events, or topics. As with any decision, to post a tweet referring to politics is subject to a host of individual-level influences.

Conversing about politics on Twitter requires that a political topic has caught the user's interest. Accordingly, users with high levels of political interest are more likely to refer to political events, actors, or topics in their messages than other users. For them, it is intrinsically rewarding to search for and share political information as well as to try to affect politics, be it offline or online. The strong connection between political interest and Internet use has been repeatedly shown (e.g., Bimber, 2001; Boulianne, 2009). It therefore comes as no surprise to find political Twitter use also to be strongly connected with high levels of political interests (e.g., Gainous & Wagner, 2014; Rainie et al., 2012; Vaccari et al., 2013). When the costs of gathering political information diminish, even politically less interested users might converse about politics. So, mediated political events and topics might be likely to catch the attention of users beyond the circle of the politically attentive. This qualification notwithstanding, political interest is correlated with comparatively strong political preferences, including partisan attachments (e.g., Lodge & Taber, 2013). Thus, most political commentary on Twitter likely stems from partisans (e.g., Barberá and Rivero, 2014; Bekafigo and McBride, 2013; Huberty, 2015).

In addition to the intensity of political interest and political preferences, Twitter users might differ from the general public also in the fields of substantive interest and political leanings. To begin with, Twitter users are Internet savvy and, therefore, are likely to pay more attention to political issues concerning the Internet than the general public. So, these issues are likely overrepresented in online communication as compared to their prominence with the population at large (e.g. Olmstead et al., 2014). When it comes to party preferences, some mechanisms suggest that the composition of Twitter users differs from a random sample from the general public. First, their interest in Internet politics suggests that supporters of parties with this issue focus will be overrepresented on Twitter. Second, given differences in the age and education distributions of the various parties' supporters, Twitter users are likely to comprise an above-average proportion of supporters of parties that are preferred by young and highly educated voters (e.g. Mitchell & Guskin, 2013). Depending on the nature of party systems, supporters of certain parties, e.g. liberals or libertarians, might be overrepresented. Third, supporters of parties who find the position of their party to be underrepresented in the media or in public discourse might rely disproportionally on digital services to voice their opinions and link to supporting coverage on the web than supporters of parties well represented in the media.

In summary, we cannot take it for granted that Twitter users referring to politics resemble the general public in terms of the intensity of political interest and preferences as well as fields of substantive interest and partisan preferences. Accordingly, the political topics, actors, and events prominent on Twitter are not likely to resemble those prominent in politics at large.

Influences based on technology

Twitter forces its users to express themselves in text messages of 140 characters or less. This limitation influences the kind of political comments likely to be found on Twitter. 140 characters are well suited for short statements of affirmation or critique, pithy one-liners, or links to content on the web. This element of Twitter's design makes it an unlikely space for extended analyses, commentary, or deliberative exchanges. This technological limitation has also led to the emergence of a series of usage conventions, short sets of characters with which users are able to anchor their messages in a greater thematic context (i.e. hashtags), interact with each other (i.e. @messages or @mentions), link to content on the web (i.e. link shorteners) and to alert their followers to interesting content posted by other users (i.e. retweets). While these conventions help users to express themselves more fully in the limit of 140 characters they also influence the mediation of politics. Also, Twitter increasingly introduces algorithms based on user behavior and paid content in decisions to prominently display content. These practices might also influence reflections of social reality found in digital trace data (e.g. Strohmaier & Wagner, 2014).

Testing the model

We can test this model by comparing measurements of political reality emerging from digital trace data collected on Twitter with more traditional measurements of political reality.2 To be sure, this comparison does not represent a formal test of the mediation model, but it enables us to assess if it is reasonable to think of Twitter data as a mirror to political life or a skewed reflection. For this, we focus on three patterns found in aggregates of Twitter messages referring to politics: spikes in the daily volume of Twitter messages referring to politics and their relationship to political events during the campaign; prominent topics in Twitter messages compared to prominent topics in surveys and in television news programs; and, mention shares of parties and candidates compared to their relative performance on election night.

Methods

The backbone of this analysis is a collection of Twitter messages referring to politics posted between 1 July and 22 September 2013, the run-up to the German federal election. We queried the Historical Powertrack of Twitter's official data vendor Gnip for messages containing the names of political parties, candidates, campaign-related phrases, and keywords related to campaign-related media events.3 This initial dataset covering all public Twitter messages using the queried character strings as keywords or hashtags includes 6,677,795 messages posted by 1,248,667 users. To ensure that the messages included in the analysis were actually referring to German politics and the campaign, we filtered these messages based on their propensity to refer to German politics. Lacking an exact technique to identify the language of a tweet or the nationality of a user, we included all messages posted by users who had chosen German as interface language in interacting with Twitter. This resulted in a total of 1,391,187 messages posted by 98,166 users. This subset of the original dataset serves as basis for the analysis of Twitter-based metrics.

The first step of our analysis examines whether spikes in the daily volume of Twitter messages referring to politics coincided with important events during the campaigns. We aggregated all messages using one of the terms listed in Endnote 3 either as keyword or as hashtag in daily sums. The term “keywords” refers to the use of selected character strings as words in a tweet. This is different from the use of the selected character strings preceded by a hashtag sign, since these “hashtags” are a Twitter convention used to anchor a tweet in a given context. The use of hashtags might be more prevalent with experienced Twitter users than with novices and thus follow different dynamics than the use of keywords. To create a baseline of key events during the campaign, we used the extensive campaign-event calendar provided by the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES) (Rattinger et al., 2015). Following Jungherr (2015), we coded the listed events as independent events, controversies, campaign-initiated, media-initiated (cf. Molotch & Lester 1974), and media events (cf. Dayan & Katz, 1992). This strategy enables us to examine which event type creates spikes in political Twitter activity.

Analyzing prominent topics on Twitter and comparing them with dominant political topics during the campaign raises a series of issues. First, we have to decide on how to measure dominant topics on Twitter. While traditional surveys can directly query respondents for the topics they deem most important, analyzing Twitter data requires the detection of common topics in aggregate collections of Twitter messages. On Twitter, hashtags are used to explicitly contextualize messages. We, therefore, use hashtags as an indicator of topics addressed by users in their tweets. Here we focus on the 100 most often used hashtags in messages posted between 8 July and 21 September 2013 containing one of the character strings listed in Endnote 3. This enables us to identify the most prominent topics in politically relevant messages posted during the run of the campaign. We coded the hashtags according to the political context they refer to (i.e. aspects of the campaign, political issues, political television programs, or other topics). We then aggregated the usage count for the hashtags in each category and calculated the mention share each category had on all mentions of the 100 hashtags used most often. This enables an assessment of their relative prominence. To examine which topics were most prominent in the public's mind, we used the GLES Rolling Cross Section (RCS). This CATI survey queried 7,882 randomly chosen respondents from 8 July to 21 September 2013 (for details on the data set see Rattinger et al., 2014). Respondents were asked to identify the two most pressing political problems in Germany. We aggregated the weighted mentions of the most and the second most important topics and ranked them according to their shares of the total count of all topic mentions.4 For the identification of prominent topics in TV news programs, we relied on the GLES Campaign Content Analysis, Television, providing a hand-coded account of the content of the major news programs of Germany's four major TV stations (ARD, ZDF, RTL, Sat.1) (Rattinger et al., 2015). From 8 July to 21 September 2013 the dataset contains 1,017 program items relevant to German politics, of these, 712 items refer to policy issues, 321 to the campaign, and 162 to specific controversies. We grouped these items according to the policy issues, element of the campaign, or controversy they refer to. This enables a comparison of the topics prominent in the voters' mind, television news, and on Twitter from 8 July to 21 September.

In the final step of the analysis, we compare the relative attention paid to parties and leading candidates with their vote share on election night. To this end, we aggregated all mentions of political parties and leading candidates by keywords or hashtags in Twitter messages posted between 1 July and 22 September 2013. To identify respective mentions, we used the character strings listed in Endnote 3. We then calculated the mention share each party received of all party mentions and the share each candidate received of all candidate mentions. Finally, we compared these mention shares with the vote share of the respective actors.

Results

In our attempt to examine the relationship between political reality at large and the reflection of politics visible in Twitter messages posted during the German federal election campaign in 2013, we focus on three patterns found in aggregates of messages referring to politics: spikes in the daily volume of Twitter messages referring to politics and their relationship to political events during the campaign; prominent topics in Twitter messages compared to prominent topics in surveys and in television news programs; and mention shares of parties and candidates compared to their relative performance on election night. By identifying specific deviations between political reality at large and political reality as represented in Twitter messages, we will explore the mediating influences discussed above.

Political events

The clearest view of which events create traces in Twitter data emerges once we examine the daily fluctuations in the volume of Twitter messages referring to politics. Figure 2 shows the daily fluctuations in the volume of Twitter messages referring to politics by keyword or hashtag. Both time series have a stable baseline of less than 10,000 politically relevant messages per day up until the day of the televised leaders' debate. On that day—1 September—the volume of messages using politically relevant keywords or hashtags spikes at just under 60,000 messages. Following that date, the number of relevant messages drops back to nearly its former daily level. The daily use of politically relevant hashtags then follows a slight upward trend, only to spike strongly on Election Day—22 September—at above 130,000 messages. The daily use of politically relevant keywords follows a similar but less pronounced pattern, with Election Day being an exception, when messages using politically relevant hashtags dwarfed the number of messages containing political keywords. Accordingly, we can largely dismiss the possibility that the use of hashtags by a more Twitter-savvy population introduces diverging temporal patterns.

Counts of Twitter messages containing either politically relevant keywords or hashtags5

These patterns are repeatedly broken on days during which the volume of relevant Twitter messages reaches a local maximum only to fall back to its former level a few days later. The most profound of these relative volume spikes are listed in Table 1 together with the political events or topics that were driving this increased volume. The first relative spike falls on 19 July. Examining the content of tweets posted on that day showed that messages were referring to Chancellor Merkel's comments on the ongoing NSA surveillance controversy in a press conference. The spike on August 26 was produced by multithreaded conversations on Twitter and not by reactions to a single event or topic. The massive spike on 1 September was produced by messages referring to the televised leaders' debate between Chancellor Merkel (CDU) and her challenger Peer Steinbrück (SPD). On 9 and 11 September 2013 the spikes reacted to appearances of Merkel and Steinbrück on the political TV-show “Wahlarena.” On 15 September, messages increased in reaction to the state election in Bavaria while the final spike on 22 September was due to the federal election. This pattern suggests that Twitter users reacted most heavily to political media events—such as a televised leaders' debate and election night coverage—, a selection of prominent events initiated by the media, such as the program “Wahlarena,” and events related to internet-related controversies, such as the NSA surveillance controversy.

Events in focus of Twitter messages posted during days of exceptionally high activity

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-19 | Merkel comments in press conference on NSA controversy | controversy |

| 2013-08-26 | Various topics, no clear focus | - |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate | media event |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Angela Merkel | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Peer Steinbrück | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State election, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-22 | Federal election / State elections, Hessen | media event |

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-19 | Merkel comments in press conference on NSA controversy | controversy |

| 2013-08-26 | Various topics, no clear focus | - |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate | media event |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Angela Merkel | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Peer Steinbrück | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State election, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-22 | Federal election / State elections, Hessen | media event |

Events in focus of Twitter messages posted during days of exceptionally high activity

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-19 | Merkel comments in press conference on NSA controversy | controversy |

| 2013-08-26 | Various topics, no clear focus | - |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate | media event |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Angela Merkel | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Peer Steinbrück | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State election, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-22 | Federal election / State elections, Hessen | media event |

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-19 | Merkel comments in press conference on NSA controversy | controversy |

| 2013-08-26 | Various topics, no clear focus | - |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate | media event |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Angela Merkel | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Peer Steinbrück | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State election, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-22 | Federal election / State elections, Hessen | media event |

Although relative spikes in the volume of politically relevant tweets are connected with political events, they provide a far from comprehensive picture of events relevant to the campaign. Table 2 lists key-events during the 2013 election campaign as provided by the GLES campaign-event calendar (Rattinger et al., 2015). A comparison between Table 1 and Table 2 shows that relying on spikes in Twitter volume to identify important key events leads researchers to miss all campaign-initiated events (such as campaign trips or party conventions), most media-initiated events (such as high-profile interviews with leading candidates and the televised debate of leading candidates of smaller parties), most controversies during the campaign (such as the controversy about the role of pedophiles in the founding of Germany's Green Party or a controversial magazine cover showing the leading candidate, Steinbrück (SPD), giving the finger), and also important independent events (e.g. the resignation of Brandenburg's prime minister).

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-07 | ARD-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-14 | ARD-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Trittin (Die Grünen) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-19 | Party convention CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-20 | Summer campaign trips by leading candidates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-21 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-28 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-29 | Platzeck (SPD) prime minister of Brandenburg announces resignation | independent |

| 2013-07-30 | Official start of campaign, Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-04 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-10 | Start of controversy about support of pedophiles in founding phase of Germany's FDP and Die Grünen | controversy |

| 2013-08-11 | ARD-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-17 | Deutschlandfest, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-18 | ARD-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-24 | Attack on Lucke (AfD) during campaign event | independent |

| 2013-08-25 | ARD-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-28 | Woidke (SPD) is sworn in as new Governor of Brandenburg | independent |

| 2013-08-29 | Steinbrück (SPD) presents campaign program | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate (Merkel, Steinbrück) | media event |

| 2013-09-02 - 2013-09-06 | G20-Summit St. Petersburg | independent |

| 2013-09-02 | Televised leaders' debate, opposition parties | media event |

| 2013-09-05 | Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-08 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, Die Grünen | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Party convention, Die LINKE | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-12 | Party convention, CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-13 | Publication of controversial photograph of Steinbrück (SPD) | controversy |

| 2013-09-14 | Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State elections, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-16 | Trittin (Die Grünen) is involved in the pedophilia scandal of his party | controversy |

| 2013-09-19 | Party convention, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-19 | TV total, election special | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 - 2013-09-21 | Party convention (online), Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 | Party convention, Die LINKE / Party convention, Die Grünen / Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-21 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-22 | State elections, Hessen / Federal election | media event |

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-07 | ARD-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-14 | ARD-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Trittin (Die Grünen) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-19 | Party convention CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-20 | Summer campaign trips by leading candidates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-21 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-28 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-29 | Platzeck (SPD) prime minister of Brandenburg announces resignation | independent |

| 2013-07-30 | Official start of campaign, Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-04 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-10 | Start of controversy about support of pedophiles in founding phase of Germany's FDP and Die Grünen | controversy |

| 2013-08-11 | ARD-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-17 | Deutschlandfest, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-18 | ARD-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-24 | Attack on Lucke (AfD) during campaign event | independent |

| 2013-08-25 | ARD-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-28 | Woidke (SPD) is sworn in as new Governor of Brandenburg | independent |

| 2013-08-29 | Steinbrück (SPD) presents campaign program | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate (Merkel, Steinbrück) | media event |

| 2013-09-02 - 2013-09-06 | G20-Summit St. Petersburg | independent |

| 2013-09-02 | Televised leaders' debate, opposition parties | media event |

| 2013-09-05 | Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-08 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, Die Grünen | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Party convention, Die LINKE | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-12 | Party convention, CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-13 | Publication of controversial photograph of Steinbrück (SPD) | controversy |

| 2013-09-14 | Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State elections, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-16 | Trittin (Die Grünen) is involved in the pedophilia scandal of his party | controversy |

| 2013-09-19 | Party convention, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-19 | TV total, election special | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 - 2013-09-21 | Party convention (online), Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 | Party convention, Die LINKE / Party convention, Die Grünen / Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-21 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-22 | State elections, Hessen / Federal election | media event |

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-07 | ARD-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-14 | ARD-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Trittin (Die Grünen) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-19 | Party convention CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-20 | Summer campaign trips by leading candidates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-21 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-28 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-29 | Platzeck (SPD) prime minister of Brandenburg announces resignation | independent |

| 2013-07-30 | Official start of campaign, Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-04 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-10 | Start of controversy about support of pedophiles in founding phase of Germany's FDP and Die Grünen | controversy |

| 2013-08-11 | ARD-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-17 | Deutschlandfest, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-18 | ARD-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-24 | Attack on Lucke (AfD) during campaign event | independent |

| 2013-08-25 | ARD-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-28 | Woidke (SPD) is sworn in as new Governor of Brandenburg | independent |

| 2013-08-29 | Steinbrück (SPD) presents campaign program | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate (Merkel, Steinbrück) | media event |

| 2013-09-02 - 2013-09-06 | G20-Summit St. Petersburg | independent |

| 2013-09-02 | Televised leaders' debate, opposition parties | media event |

| 2013-09-05 | Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-08 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, Die Grünen | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Party convention, Die LINKE | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-12 | Party convention, CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-13 | Publication of controversial photograph of Steinbrück (SPD) | controversy |

| 2013-09-14 | Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State elections, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-16 | Trittin (Die Grünen) is involved in the pedophilia scandal of his party | controversy |

| 2013-09-19 | Party convention, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-19 | TV total, election special | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 - 2013-09-21 | Party convention (online), Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 | Party convention, Die LINKE / Party convention, Die Grünen / Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-21 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-22 | State elections, Hessen / Federal election | media event |

| Date . | Event . | Type . |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-07-07 | ARD-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-14 | ARD-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Trittin (Die Grünen) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-19 | Party convention CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-18 - 2013-07-20 | Summer campaign trips by leading candidates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-07-21 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Brüderle (FDP) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-28 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) | media-initiated |

| 2013-07-29 | Platzeck (SPD) prime minister of Brandenburg announces resignation | independent |

| 2013-07-30 | Official start of campaign, Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-04 | ZDF-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-10 | Start of controversy about support of pedophiles in founding phase of Germany's FDP and Die Grünen | controversy |

| 2013-08-11 | ARD-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-17 | Deutschlandfest, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-08-18 | ARD-Summer Interview, Gysi (Die LINKE) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-24 | Attack on Lucke (AfD) during campaign event | independent |

| 2013-08-25 | ARD-Summer Interview, Steinbrück (SPD) / ZDF-Summer Interview, Seehofer (CSU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-08-28 | Woidke (SPD) is sworn in as new Governor of Brandenburg | independent |

| 2013-08-29 | Steinbrück (SPD) presents campaign program | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-01 | Televised leaders' debate (Merkel, Steinbrück) | media event |

| 2013-09-02 - 2013-09-06 | G20-Summit St. Petersburg | independent |

| 2013-09-02 | Televised leaders' debate, opposition parties | media event |

| 2013-09-05 | Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-08 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, Die Grünen | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Party convention, Die LINKE | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-09 | Wahlarena, Merkel (CDU) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-11 | Wahlarena, Steinbrück (SPD) | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-12 | Party convention, CSU | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-13 | Publication of controversial photograph of Steinbrück (SPD) | controversy |

| 2013-09-14 | Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-15 | State elections, Bayern | media event |

| 2013-09-16 | Trittin (Die Grünen) is involved in the pedophilia scandal of his party | controversy |

| 2013-09-19 | Party convention, SPD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-19 | TV total, election special | media-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 - 2013-09-21 | Party convention (online), Pirates | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-20 | Party convention, Die LINKE / Party convention, Die Grünen / Party convention, AfD | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-21 | Party convention, CDU / Party convention, FDP | campaign-initiated |

| 2013-09-22 | State elections, Hessen / Federal election | media event |

The empirical patterns support, rather than disconfirm, our model. Twitter users reacted to specific political events by posting more tweets referring to politics than on normal days. This influence of political reality on Twitter activity is mediated by interests and attention towards politics by Twitter users. Still, the selection of events that led to these increases in tweets offered only a view of political events filtered by the interests of Twitter users (such as the controversy regarding NSA surveillance) and attention (such as media events and a selection of high-profile political TV programs). Accordingly, influences at the level of social and political reality and individual interests and behavior of Twitter users appear to lead political reality as found on Twitter to deviate from political reality at large.

Dominant topics

Comparing prominent topics in the public's mind, in television news programs, and in politically relevant Twitter messages also supports the view of Twitter offering a mediated image of political reality. Table 3 shows the 10 most pressing political topics as given by RCS respondents (Rattinger et al., 2014). Accordingly, the financial crisis, unemployment, education and labor policy dominated the public's mind during the campaign.6

| Rank . | Topics, GLES RCS . | Share of mentions . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 11.7 |

| 2 | Unemployment | 10.7 |

| 3 | Education | 6.7 |

| 4 | Labor Policy | 6.2 |

| 5 | Retirement benefits | 6.1 |

| 6 | Wealth distribution, justice of | 5.2 |

| 7 | Economy | 4.4 |

| 8 | Family policy | 4.3 |

| 9 | Migration | 4.3 |

| 10 | Energy policy | 4.2 |

| Rank . | Topics, GLES RCS . | Share of mentions . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 11.7 |

| 2 | Unemployment | 10.7 |

| 3 | Education | 6.7 |

| 4 | Labor Policy | 6.2 |

| 5 | Retirement benefits | 6.1 |

| 6 | Wealth distribution, justice of | 5.2 |

| 7 | Economy | 4.4 |

| 8 | Family policy | 4.3 |

| 9 | Migration | 4.3 |

| 10 | Energy policy | 4.2 |

| Rank . | Topics, GLES RCS . | Share of mentions . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 11.7 |

| 2 | Unemployment | 10.7 |

| 3 | Education | 6.7 |

| 4 | Labor Policy | 6.2 |

| 5 | Retirement benefits | 6.1 |

| 6 | Wealth distribution, justice of | 5.2 |

| 7 | Economy | 4.4 |

| 8 | Family policy | 4.3 |

| 9 | Migration | 4.3 |

| 10 | Energy policy | 4.2 |

| Rank . | Topics, GLES RCS . | Share of mentions . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 11.7 |

| 2 | Unemployment | 10.7 |

| 3 | Education | 6.7 |

| 4 | Labor Policy | 6.2 |

| 5 | Retirement benefits | 6.1 |

| 6 | Wealth distribution, justice of | 5.2 |

| 7 | Economy | 4.4 |

| 8 | Family policy | 4.3 |

| 9 | Migration | 4.3 |

| 10 | Energy policy | 4.2 |

Table 4 reports the political topics most prominent in Germany's major news programs as measured by the GLES Campaign Content Analysis, Television (Rattinger et al., 2015). The evidence shows that 70.0% of the relevant items refer to policy issues, 31.6% to the campaign, and 15.9% to specific controversies. Among the 10 most referred to policy issues, international crises, transportation policy, defense, and family policy dominate. Of the 10 topics most prominent among RCS respondents, only the financial crisis appears.

Dominant topics in television news coverage during the campaign (July 8 to September 21, 2013)

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of all relevant news items . | Share of all items in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy issues | 70.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.4 | ||

| Transportation policy | 8.9 | ||

| Defense | 6.6 | ||

| Family policy | 5.8 | ||

| Health policy | 5.3 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 5.2 | ||

| Energy policy | 4.5 | ||

| Homeland security | 4.5 | ||

| Foreign policy | 3.8 | ||

| Europe | 3.5 | ||

| Campaign | 31.6 | ||

| General | 60.1 | ||

| State elections | 13.7 | ||

| Poll results | 9.7 | ||

| Televised leaders' debate | 9.4 | ||

| Party platforms | 7.27 | ||

| Controversies | 15.9 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 82.7 | ||

| Steinbrück magazine cover | 10.5 | ||

| Resignation of Brandenburg's prime minister | 4.3 | ||

| Plagiarism by politicians | 2.5 |

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of all relevant news items . | Share of all items in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy issues | 70.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.4 | ||

| Transportation policy | 8.9 | ||

| Defense | 6.6 | ||

| Family policy | 5.8 | ||

| Health policy | 5.3 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 5.2 | ||

| Energy policy | 4.5 | ||

| Homeland security | 4.5 | ||

| Foreign policy | 3.8 | ||

| Europe | 3.5 | ||

| Campaign | 31.6 | ||

| General | 60.1 | ||

| State elections | 13.7 | ||

| Poll results | 9.7 | ||

| Televised leaders' debate | 9.4 | ||

| Party platforms | 7.27 | ||

| Controversies | 15.9 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 82.7 | ||

| Steinbrück magazine cover | 10.5 | ||

| Resignation of Brandenburg's prime minister | 4.3 | ||

| Plagiarism by politicians | 2.5 |

Shares of topics do not add up to 100 as various items were coded as referring to more than one topic. Of the policy issues covered by television news, we list the ten most prominent. For the share of policy issues in news items we included all topics.

Dominant topics in television news coverage during the campaign (July 8 to September 21, 2013)

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of all relevant news items . | Share of all items in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy issues | 70.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.4 | ||

| Transportation policy | 8.9 | ||

| Defense | 6.6 | ||

| Family policy | 5.8 | ||

| Health policy | 5.3 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 5.2 | ||

| Energy policy | 4.5 | ||

| Homeland security | 4.5 | ||

| Foreign policy | 3.8 | ||

| Europe | 3.5 | ||

| Campaign | 31.6 | ||

| General | 60.1 | ||

| State elections | 13.7 | ||

| Poll results | 9.7 | ||

| Televised leaders' debate | 9.4 | ||

| Party platforms | 7.27 | ||

| Controversies | 15.9 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 82.7 | ||

| Steinbrück magazine cover | 10.5 | ||

| Resignation of Brandenburg's prime minister | 4.3 | ||

| Plagiarism by politicians | 2.5 |

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of all relevant news items . | Share of all items in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy issues | 70.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.4 | ||

| Transportation policy | 8.9 | ||

| Defense | 6.6 | ||

| Family policy | 5.8 | ||

| Health policy | 5.3 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 5.2 | ||

| Energy policy | 4.5 | ||

| Homeland security | 4.5 | ||

| Foreign policy | 3.8 | ||

| Europe | 3.5 | ||

| Campaign | 31.6 | ||

| General | 60.1 | ||

| State elections | 13.7 | ||

| Poll results | 9.7 | ||

| Televised leaders' debate | 9.4 | ||

| Party platforms | 7.27 | ||

| Controversies | 15.9 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 82.7 | ||

| Steinbrück magazine cover | 10.5 | ||

| Resignation of Brandenburg's prime minister | 4.3 | ||

| Plagiarism by politicians | 2.5 |

Shares of topics do not add up to 100 as various items were coded as referring to more than one topic. Of the policy issues covered by television news, we list the ten most prominent. For the share of policy issues in news items we included all topics.

The evidence on the dominant topics in the 100 hashtags most often used in politically relevant messages gives rise to a different conclusion (Table 5). Most hashtags refer to the campaign, accounting for 71.4% of all mentions. The second most prominent hashtag group concerns political television programs (such as the televised leaders' debate), accounting for 17.2% of all mentions, thereby suggesting that Twitter as a communication environment is highly interconnected with traditional media (cf. Jungherr, 2014). The third most prominent group comprises hashtags addressing political controversies, accounting for 5.0% of all mentions. Hashtags related to political issues rank last with only 1.6%. Most politically relevant messages, therefore, concern the campaign and coverage by traditional media. Only a small minority of messages appears to react to political topics. Moreover, the issues mentioned in tweets—the controversy about NSA surveillance and internet policy—conform to the specific interests of Twitter's user base. These findings again support our model, as the image of political reality arising from Twitter messages appears to be mediated by interests and attention of its users.

Dominant topics in the top 100 ranked hashtags used in politically relevant messages (July 8 to September 21, 2013)

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of top 100 hashtag mentions . | Share of hashtag mentions in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campaign | 71.4 | ||

| Party | 57.1 | ||

| General | 23.0 | ||

| Politician | 15.3 | ||

| State elections | 3.8 | ||

| Activism | 0.6 | ||

| Satire | 0.3 | ||

| Television | 17.2 | ||

| Leaders' debate | 71.4 | ||

| Various political programs | 23.1 | ||

| General | 5.4 | ||

| Controversies | 5.0 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 93.5 | ||

| Role of pedophiles in founding period of Germany's Green party | 3.4 | ||

| Steinbrück (SPD) flips finger on magazine cover | 3.4 | ||

| Other | 4.9 | ||

| Issues | 1.6 | ||

| Internet policy | 29.7 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 29.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.8 | ||

| Energy | 16.4 | ||

| Labor policy | 8.1 |

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of top 100 hashtag mentions . | Share of hashtag mentions in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campaign | 71.4 | ||

| Party | 57.1 | ||

| General | 23.0 | ||

| Politician | 15.3 | ||

| State elections | 3.8 | ||

| Activism | 0.6 | ||

| Satire | 0.3 | ||

| Television | 17.2 | ||

| Leaders' debate | 71.4 | ||

| Various political programs | 23.1 | ||

| General | 5.4 | ||

| Controversies | 5.0 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 93.5 | ||

| Role of pedophiles in founding period of Germany's Green party | 3.4 | ||

| Steinbrück (SPD) flips finger on magazine cover | 3.4 | ||

| Other | 4.9 | ||

| Issues | 1.6 | ||

| Internet policy | 29.7 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 29.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.8 | ||

| Energy | 16.4 | ||

| Labor policy | 8.1 |

Dominant topics in the top 100 ranked hashtags used in politically relevant messages (July 8 to September 21, 2013)

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of top 100 hashtag mentions . | Share of hashtag mentions in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campaign | 71.4 | ||

| Party | 57.1 | ||

| General | 23.0 | ||

| Politician | 15.3 | ||

| State elections | 3.8 | ||

| Activism | 0.6 | ||

| Satire | 0.3 | ||

| Television | 17.2 | ||

| Leaders' debate | 71.4 | ||

| Various political programs | 23.1 | ||

| General | 5.4 | ||

| Controversies | 5.0 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 93.5 | ||

| Role of pedophiles in founding period of Germany's Green party | 3.4 | ||

| Steinbrück (SPD) flips finger on magazine cover | 3.4 | ||

| Other | 4.9 | ||

| Issues | 1.6 | ||

| Internet policy | 29.7 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 29.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.8 | ||

| Energy | 16.4 | ||

| Labor policy | 8.1 |

| Topic . | Subtopic . | Share of top 100 hashtag mentions . | Share of hashtag mentions in category . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campaign | 71.4 | ||

| Party | 57.1 | ||

| General | 23.0 | ||

| Politician | 15.3 | ||

| State elections | 3.8 | ||

| Activism | 0.6 | ||

| Satire | 0.3 | ||

| Television | 17.2 | ||

| Leaders' debate | 71.4 | ||

| Various political programs | 23.1 | ||

| General | 5.4 | ||

| Controversies | 5.0 | ||

| NSA surveillance | 93.5 | ||

| Role of pedophiles in founding period of Germany's Green party | 3.4 | ||

| Steinbrück (SPD) flips finger on magazine cover | 3.4 | ||

| Other | 4.9 | ||

| Issues | 1.6 | ||

| Internet policy | 29.7 | ||

| Financial Crisis/Euro Crisis | 29.0 | ||

| International crises | 16.8 | ||

| Energy | 16.4 | ||

| Labor policy | 8.1 |

Mentions of parties and candidates

In a final step, we compare mentions of parties, and candidates on Twitter and their relative importance indicated by election results. Although Twitter mentions of political actors and their subsequent electoral fortunes are unlikely to be causally linked, both metrics may provide insights into what drives mentions of political actors.

From July 1 to September 22, 2013, parties were mentioned in 300,808 Twitter messages by keywords included in our analysis. 542,594 messages contained party mentions by hashtag. Table 6 reports mention shares of parties and their vote shares on Election Day in 2013. The evidence suggests that new parties—such as the Pirate Party and the Alternative for Germany (AfD)—were very prominent according to their share of party mentions while receiving comparatively small vote shares. Traditional parties—such as CDU/CSU and SPD—were mentioned on par—when counting keyword mentions—or even less than the AfD or the Pirates—when focusing on hashtag mentions—while still receiving a majority of the votes. Thus, Twitter appears to be a nonnormalized communication environment (cf. Schweitzer, 2011). Relying on Twitter to draw inferences about public opinion toward political parties thus leads to ill-founded conclusions.

| Party . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . | 2013, election results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | 17.7 | 19.8 | 42.5 |

| SPD | 18.4 | 12.5 | 25.7 |

| Die LINKE | 12.0 | 5.5 | 8.6 |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | 8.6 | 6.5 | 8.4 |

| FDP | 17.7 | 12.3 | 4.8 |

| AfD | 10.8 | 17.3 | 4.7 |

| Piratenpartei | 15.0 | 26.2 | 2.2 |

| Party . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . | 2013, election results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | 17.7 | 19.8 | 42.5 |

| SPD | 18.4 | 12.5 | 25.7 |

| Die LINKE | 12.0 | 5.5 | 8.6 |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | 8.6 | 6.5 | 8.4 |

| FDP | 17.7 | 12.3 | 4.8 |

| AfD | 10.8 | 17.3 | 4.7 |

| Piratenpartei | 15.0 | 26.2 | 2.2 |

| Party . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . | 2013, election results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | 17.7 | 19.8 | 42.5 |

| SPD | 18.4 | 12.5 | 25.7 |

| Die LINKE | 12.0 | 5.5 | 8.6 |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | 8.6 | 6.5 | 8.4 |

| FDP | 17.7 | 12.3 | 4.8 |

| AfD | 10.8 | 17.3 | 4.7 |

| Piratenpartei | 15.0 | 26.2 | 2.2 |

| Party . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . | 2013, election results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | 17.7 | 19.8 | 42.5 |

| SPD | 18.4 | 12.5 | 25.7 |

| Die LINKE | 12.0 | 5.5 | 8.6 |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | 8.6 | 6.5 | 8.4 |

| FDP | 17.7 | 12.3 | 4.8 |

| AfD | 10.8 | 17.3 | 4.7 |

| Piratenpartei | 15.0 | 26.2 | 2.2 |

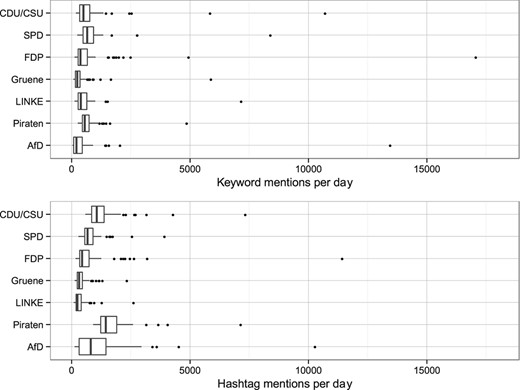

As suggested above, in general, spikes in the volume of politically relevant Twitter messages can be conceived of as reactions to political events grabbing the attention of Twitter users. This notion also fits nicely with the evidence concerning the mentions of political parties. Figure 3 shows boxplots documenting the distribution of daily mentions of political parties in the campaign. The dots in the plot mark outliers—daily mention counts, lying far beyond the usual fluctuations of daily mentions of a party. Examining the data providing the basis for these boxplots shows that nearly all outliers fall on days on which specific events connected with the respective political party happened—such as election days or the televised leaders' debate.

While most outliers in the daily volume of party mentions on Twitter appear to be driven by the attention of Twitter users to specific political events, the total volume of a party's mentions appears to be driven by the level of its mentions on days without specific events. The boxplots identify the median value of daily party mentions on Twitter by a black vertical line. On half of the days in the analysis, the parties received fewer mentions than this value while on the other half they received more. The median value of daily party mentions on Twitter is, therefore, a good indicator for the level of mentions parties achieved without exceptional events focusing the attention of Twitter users. Comparatively high median values might thus indicate a steady interest in a party, be it positive or negative. This activity stems probably from political partisans, either in support for or opposition to a given party. This reading is supported by an examination of the parties showing rather high median mention levels, i.e. CDU/CSU, the Pirate Party, and the AfD. The Pirates and the AfD were controversial and had strong supporter bases online, while the CDU/CSU was likely to win the election and thereby object of discussion online.

This example suggests that political interests and attention toward selected political actors influenced the mediation of politics through Twitter. The mention counts of political parties did not reflect their relative importance during the campaign or their electoral chances. Instead, mention counts reflect the steady attention paid to a selection of political parties based on the political interests and partisan leanings of Twitter users. This conclusion is additionally bolstered by evidence on the daily mention counts of popular political candidates.

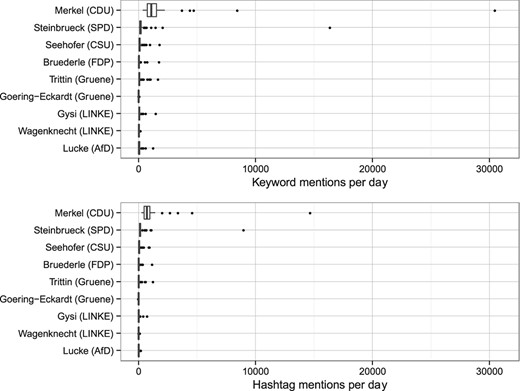

In general, political candidates were mentioned much less frequently in hashtags than parties. From 1 July to 22 September, we counted 203,170 messages with keyword and 130,350 messages with hashtag mentions of leading candidates. Table 7 shows that the leading candidates of CDU and SPD dominated in hashtag mentions of candidates by far—with the incumbent Chancellor Merkel dominating candidate mentions with a share of 62.2% of all keyword and 64.6% of all hashtag mentions. The references to candidates in Twitter messages focused almost exclusively on the two candidates for chancellor. In this regard, Twitter is a normalized communication space, dominated by political actors of focal interest in the electoral process. These actors appear to elicit a steady stream of mentions, independent of specific events.

| Party . | Candidate . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | Angela Merkel | 62.2 | 64.6 |

| Horst Seehofer | 5.7 | 6.5 | |

| SPD | Peer Steinbrück | 15.7 | 17.1 |

| Die LINKE | Gregor Gysi | 3.9 | 2.8 |

| Sahra Wagenknecht | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | Katrin Göring-Eckardt | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Jürgen Trittin | 4.7 | 4.0 | |

| FDP | Rainer Brüderle | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| AfD | Bernd Lucke | 3.6 | 1.7 |

| Party . | Candidate . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | Angela Merkel | 62.2 | 64.6 |

| Horst Seehofer | 5.7 | 6.5 | |

| SPD | Peer Steinbrück | 15.7 | 17.1 |

| Die LINKE | Gregor Gysi | 3.9 | 2.8 |

| Sahra Wagenknecht | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | Katrin Göring-Eckardt | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Jürgen Trittin | 4.7 | 4.0 | |

| FDP | Rainer Brüderle | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| AfD | Bernd Lucke | 3.6 | 1.7 |

| Party . | Candidate . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | Angela Merkel | 62.2 | 64.6 |

| Horst Seehofer | 5.7 | 6.5 | |

| SPD | Peer Steinbrück | 15.7 | 17.1 |

| Die LINKE | Gregor Gysi | 3.9 | 2.8 |

| Sahra Wagenknecht | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | Katrin Göring-Eckardt | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Jürgen Trittin | 4.7 | 4.0 | |

| FDP | Rainer Brüderle | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| AfD | Bernd Lucke | 3.6 | 1.7 |

| Party . | Candidate . | Keyword share . | Hashtag share . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDU/CSU | Angela Merkel | 62.2 | 64.6 |

| Horst Seehofer | 5.7 | 6.5 | |

| SPD | Peer Steinbrück | 15.7 | 17.1 |

| Die LINKE | Gregor Gysi | 3.9 | 2.8 |

| Sahra Wagenknecht | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | Katrin Göring-Eckardt | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Jürgen Trittin | 4.7 | 4.0 | |

| FDP | Rainer Brüderle | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| AfD | Bernd Lucke | 3.6 | 1.7 |

Figure 4 shows that the distributions of candidate mentions are again dominated by a mix of event-based influences, as seen in the outliers present for every candidate, and the influence of political interests and attention, as seen in the varying median mention levels for each candidate. Angela Merkel dominates again the daily mention counts of candidates. This suggests that mention counts of political actors are dominated by symbolic figures constantly attracting the attention of politically interested Twitter users. The mentions of other political actors are more event-dependent. Political reality, as mirrored by Twitter data, therefore, nearly exclusively accounts for few political actors either binding the attention of Twitter users by their symbolic competition for the Chancellorship or by the controversies they elicit. Candidates of smaller parties are all but invisible in the messages posted by politically vocal Twitter users. These findings again support our model.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate that political reality as found in aggregates of Twitter messages diverges from political reality as measured by traditional metrics and thereby probably also from political reality at large. This is true for political events, popular topics of discussion, and attention towards political actors. The divergence between political reality and the parts of it mirrored in Twitter messages suggests some caution expecting Twitter data to provide a true image of political reality. Instead, the evidence is in line with a model suggesting that this divergence results from the interplay of factors influencing the mediation of political reality through Twitter. To be sure, the evidence did not permit to scrutinize microlevel processes in depth. But the analysis suggests that this model is fruitful in analyzing the relationship between political reality and Twitter communication.

These findings have clear implications for researchers and the public in interpreting patterns found in digital trace data. As the importance of digital services in the public construction of social and political reality grows, researchers and the public have to start focusing on the mediating factors of digital services that might lead to systematic distortions of reality reflected through digital trace data. Here, researchers have to start incorporating and adapting the rich literature on the mediation of reality through traditional media in their work.

Building on the model presented here, tracing macrolevel phenomena back to microlevel processes, scholars might be well-advised to consider some refocusing in the research on digital trace data. Aggregate statistics on Twitter communication result from data-generating processes comprising decisions of a host of users. Following this, case studies identifying aggregate correlations between Twitter metrics and real-world phenomena might bear not as many insights as hoped for or even fall victim to an ecological fallacy. The framework described above also suggests more comparative research. By comparing the fit of Twitter communication and real-world phenomena at different points in time (e.g., campaigns and noncampaign periods), on different topics (e.g., political vs. nonpolitical), in different societies, and different channels (e.g., Twitter vs. Facebook vs. Google), scholars might improve our understanding of the processes leading to the emergences of specific patterns in aggregated digital trace data and their relationship to social and political phenomena. Any such endeavor also has to systematically address the choice of appropriate comparisons between traditional metrics of political reality and digital trace data. Digital trace data are found data (cf. Howison et al., 2011), therefore, researchers have to theorize links between signals contained in digital trace data and social or political phenomena of interest (cf. Rogers, 2013). Similar attention has to be paid on justifying the choice of comparative measurements. For example, identifying topics mentioned by Twitter users in tweets might document a different type of salient topics, than those identified by surveys in response to an explicit question for the most important political topic at the time. This suggests testing a variety of measures of various aspects of political reality on their links and divergences to various metrics based on digital trace data collected on various services, to gain a more general understanding of the underlying mediation processes. Finally, individual-level analysis might tackle users' decisions to post messages on Twitter in a fine-grained way. One outcome of this research might be a refinement of our simple model. Put differently, to advance the effort to understand social and political reality through digital trace data, it is important to systematically analyze the various stimulus-based, user-based, and technological mediation processes involved in creating the data traces in the first place.

For long, communication research has focused on identifying factors influencing the mediation of reality through traditional media. Finding similar processes at work in reactions to politics on digital services comes as no surprise. Still, researchers have not paid much attention to these processes. This analysis is a first attempt to fill this gap. It suggests that identifying and analyzing mediating processes of reality through digital services is mandatory to understand whether and when digital trace data are useful in the analysis of social and political phenomena and how reconstructions of social and political reality based on digital trace data might be systematically distorted.

Notes

We use the term “mediation” or “mediated communication” in the sense of Shoemaker & Reese (2014), meaning communication filtered through medium-specific processes and practices with Twitter being the medium in question. It is important to distinguish this concept from ‘mediatization’, meaning social and political changes in reaction to media logics (e.g. Hepp & Krotz, 2014).

One could argue that although we are interested in the comparison of true reality with reality emerging from digital traces, we only show that digital trace data diverge from reality as measured by traditional metrics. While it is certainly true that any measurement of social reality diverges from true reality (e.g. Hand, 2004; Herbst, 1993), these measurements come with theories connecting them with reality. Theories, we do not have with regard to digital trace data. Finding patterns in digital trace data to diverge from these traditional measurements, therefore, is the best test we have to check their accuracy with regard to reality at large.

We queried the API of Gnip's Historical Powertrack (http://support.gnip.com/apis/historical_api) for all messages containing the following character substrings irrespective of capitalization. This collection thereby contains all mentions of these strings either in keywords or hashtags and covers mentions of political parties in Germany, prominent candidates, campaign related keywords, and important campaign related media events in various spelling variations: CDU: cdu, cducsu; SPD: spd; Die LINKE: die_linke, dielinke, linke, linken, linkspartei; Bündnis 90/Die Grünen: buendnis90, bündnis90, bündnis90diegrünen, bündnis90grüne, bündnisgrüne, bündnisgrünen, die_gruenen, die_grünen, diegrünen, gruene, grüne, grünen, gruenen; CSU: csu; FDP: fdp; AfD: afd; Piratenpartei: piraten, piratenpartei. Angela Merkel: merkel, angie_merkel, angelamerkel, angela_merkel; Horst Seehofer: seehofer, horstseehofer, horst_seehofer; Peer Steinbrück steinbrück, steinbrueck, peer_steinbrück, peer_steinbrueck; Gregor Gysi: gysi, gregorgysi, gregor_gysi; Sahra Wagenknecht: wagenknecht, sahrawagenknecht, sahra_wagenknecht; Katrin Göring-Eckhardt: göring-eckardt, goering-eckardt, göringeckardt, goeringeckardt, katringöring-eckardt, katringöringeckardt, katringoering-eckardt, katringoeringeckardt, katrin_göring-eckardt, katrin_goering-eckardt, katrin_göringeckardt, katrin_goeringeckardt, katrin_göringeckardt, katrin_goeringeckardt, katrin_göring_eckardt, katrin_goering_eckardt, katringoering_eckardt, katringöring_eckardt, göring_eckardt, goering_eckardt; Jürgen Trittin: trittin, jürgentrittin, juergentrittin, jürgen_trittin, juergen_trittin; Rainer Brüderle: brüderle, bruederle, rainerbrüderle, rainerbruederle, rainer_brüderle, rainer_bruederle; Bernd Lucke: lucke, berndlucke, bernd_lucke; Campaign in general: btw13, bundestagswahl, wahlkampf, btw2013, wahl13; Important media-iniated events: tv-duell, wahlarena, dreikampf, kanzlerduell.

In addition to design weights, we employed redressment weights adjusting age, gender, education, region, and size of the place of residence, provided in the GLES RCS data set. Weighting the data does not alter the substantive conclusions of the analysis.

This and the following diagrams were produced using R (R Core Team, 2014) and ggplot2 (Wickham, 2009).

We also calculated the most prominent topics among subgroups of respondents that might resemble more closely Twitter's user base. We, therefore, specifically focused on issues mentioned by respondents who identified themselves as being very strongly or strongly interested in politics and respondents between the ages of 18 and 39. While there was some variation in the ranking of their responses, there were no large deviations from the issues given by all respondents.

References

About the Authors

Andreas Jungherr ([email protected]) is a research fellow at the chair for Political Psychology at the University of Mannheim, Germany. His research focuses on the mediation of political life online, effects of the internet on political communication, and the use of digital trace data in the social sciences.

Harald Schoen ([email protected]) holds the chair for Political Psychology at the University of Mannheim, Germany. His research areas are political psychology, political behavior, public opinion research, political online communication, and social science research methods.

Pascal Jürgens ([email protected]) is a research associate in the Department of Mass Communication at the University of Mainz, Germany. His research focuses on the diffusion of information, the fragmentation of media usage, political communication, online participation and protests, as well as computational and quantitative research methods.