-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Corné Dijkmans, Peter Kerkhof, Asuman Buyukcan-Tetik, Camiel J. Beukeboom, Online Conversation and Corporate Reputation: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study on the Effects of Exposure to the Social Media Activities of a Highly Interactive Company, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 20, Issue 6, 1 November 2015, Pages 632–648, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12132

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In this paper, we investigate whether and to what extent exposure to a company's social media activities over time is beneficial for corporate reputation, and whether conversational human voice mediates this relation. In a two-wave longitudinal survey among 1969 respondents, we assessed consumers' exposure to an international airline's social media activities, perceived level of conversational human voice and perception of corporate reputation. The results show that consumers' level of exposure to company social media activities precedes perceptions of corporate reputation. Also, conversational human voice mediates the relation between consumers' level of exposure to company social media activities and perceptions of corporate reputation. We discuss the implications of the results for the presence of organizations in social media.

Introduction

The availability of social media has changed the way organizations and consumers interact. The presence of organizations on social networking sites such as Facebook or microblogs like Twitter enables publics to complain to, or compliment organizations, to follow their content, or criticize their policies. Simultaneously, social media have provided organizations with a new venue to spread content, provide services, cocreate products or services, and more generally, to build relationships with the public (Hanna, Rohm, & Crittenden, 2011).

According to a 2012 industry study, one third of American consumers with a profile on Twitter and/or Facebook follows at least one brand, mostly on Facebook (Webster, 2012). As a result, for many organizations, a strong presence in social media has become an integral part of their communication strategy: In 2014 80% of Fortune 500 companies maintained a Facebook page, and 83% was active on Twitter at least once a month (Barnes & Lescault, 2014, October). The use of social media by companies is expected to further increase, according to a study among 350 marketing professionals (Moorman, 2014).

As a result of the growing presence of organizations in social media, the impressions people form about organizations may increasingly be based on exposure to this presence in social media. This exposure can either be self-imposed (e.g., by liking a brand page on Facebook or following a brand on Twitter) or involuntary (e.g., through promoted posts on Facebook). The main difference between traditional media (e.g., television, radio, magazines) and social media lies in the interactive and participatory character of social media. Whereas traditional media predominantly utilize one-way communication, social media has more potential to enable two-way communication – receivers are also senders, and can as well initiate contributions themselves as react to the online activities of others. Participatory online media (like social media) are well-suited platforms for what Sundar et al. (2003) defined as contingency interactivity, “a process involving users, media, and messages,” in which “communication roles need to be interchangeable for full interactivity to occur,” (p. 34–35). Kelleher (2009) found that respondents who had experienced contingency interactivity with bloggers of an organization perceived the organization as “communicating with a conversational voice.” (p. 172). The perception of a conversational human voice in turn was related to relationship characteristics such as trust, satisfaction and commitment (Kelleher, 2009). Thus, exposure to the social media activities of companies, particularly when a conversational human voice is perceived, may affect the impressions of organizations or brands, and may be different from the impressions people get from exposure to traditional media.

Exposure to interactive social media activities can be distinguished from involvement in these activities. While the former is mostly passive and related to others' behavior (i.e., watching interactions; reading), the latter also implies active participation (i.e., having interactions; contributing). Although starting to follow a brand on Twitter or Facebook can be seen as an active form of participation, the consequence of following is predominantly passive exposure to the brand's social media activities, rather than active involvement in these activities (e.g., liking, sharing, or commenting on a brand post). That is, the passive consumption of information is still the most frequently employed behavior when using social media (Romero, Galuba, Asur, & Huberman, 2011). In the current study we focus on the effects of such passive exposure to a company's social media activities, which may either result from an active choice to follow a company in social media, or from incidental or involuntary exposure to these activities.

Even while many organizations still use social media to spread traditional one-way messages (e.g., Lovejoy, Waters, & Saxton, 2012), recent findings show that a substantial number of organizations employ two-way communication strategies. These organizations engage in highly interactive conversations with the public and thereby manage to gather large audiences in social media. For example, the average response rate to questions posed on the Facebook pages of worldwide brands is 66.5% (Socialbakers, 2014), with several brands answering virtually every question they receive, often within an hour. The activities of these active brands in social media are typically a mix of customer service, reputation management, marketing, and – to a lesser degree – sales (Stelzner, 2014).

In the current study we seek empirical longitudinal evidence that exposure to a highly interactive company in social media, over time, is related to perceiving the company's communication as more human, which in turn is associated with a more positive perception of corporate reputation. The main questions of the present study are (a) whether exposure to the interactive social media activities of a company over time leads to a more positive corporate reputation and (b) whether this relation is mediated over time by the perceived level of a company's conversational human voice. To this end, we conducted a two-wave longitudinal study among almost 2000 customers and noncustomers of an international airline with a strong and highly interactive presence on both Facebook and Twitter.

In the following, we will first explicate the concepts of corporate reputation and conversational human voice (Kelleher, 2009). After detailing our methods and presenting the results, we will discuss the implications of our findings with regard to the relation over time between exposure to corporate social media activities and corporate reputation, as well as the role of conversational human voice in this relation.

Theoretical Background

Corporate Reputation

Corporate reputation has been defined as “a cognitive representation of a company's actions and results that crystallizes the firm's ability to deliver valued outcomes to its stakeholders.” (Fombrun, Gardberg, & Barnett, 2000, p. 87). According to Fombrun, Gardberg, and Sever (2000), reputation is an attitudinal construct that consists of two components: an emotional (affective) component and a rational (cognitive) component. Corporate reputation is built upon six dimensions (Fombrun & Gardberg, 2000): emotional appeal, products & services, vision & leadership, workplace environment, social & environmental responsibility, and financial performance. With this, corporate reputation is a multidimensional attitudinal outcome, and is different from other, more unidimensional concepts, such as trust or commitment.

In today's complex and highly competitive environment, corporate reputation has grown in importance. A study by Burson-Marsteller (2014) found that 95% of U.S. chief executives considered corporate reputation as important or very important in the achievement of business objectives. A positive reputation plays a role in the selection process by consumers (Walsh, Mitchell, Jackson, & Beatty, 2009) and enables companies to attract better employees, lower marketing expenses, and ask higher prices – thus strengthening the company's position (Fombrun, Gardberg, & Sever, 2000). A favorable corporate reputation can protect a company against crises (Shamma, 2012). A compromised reputation can lead to serious negative consequences, as for instance numerous financial institutions have experienced in the years after the 2007 credit crisis (e.g., Eisenegger & Künstle, 2011).

Mass media play an important role in shaping corporate reputation. Previous studies on traditional news media (e.g., newspapers, television, magazines) showed a relation between media exposure to (positive or negative) information about an organization and corporate reputation. Negative publicity can negatively affect corporate reputation (Renkema & Hoeken, 1998), whereas news about the successes of companies – such as higher profits – can improve reputation (Meijer & Kleinnijenhuis, 2006; Park & Lee, 2007). Exposure to media content thus appears to affect corporate reputation.

With the emergence of social media, the nature of media has changed. The proliferation of social media has given the public new tools to subject companies to greater and faster scrutiny. In social media, consumers not only discuss and disseminate branded content, they also create it (Waters, Burnett, Lamm, & Lucas, 2009). Fournier and Avery (2011) have labeled social media as a venue for “open source branding” in which consumers cocreate the nature and reputation of brands. Companies increasingly try to influence this process of open source branding by establishing a presence in social media. A presence in social media offers various benefits to companies, like the opportunity to communicate directly with customers, to foster relationships, stimulate co-creation, and to assess consumers' brand attitudes (de Vries, Gensler, & Leeflang, 2012; Waters et al., 2009).

The dynamics of exposure to brand information in social media are different from traditional brand exposure (e.g., mass media, advertising). In most social media, people are given the possibility to tailor information and news sources to their personal taste (Hindman, 2012). As a result – except for sponsored tweets or posts – brand exposure in social media is more often self-chosen (e.g., by deciding to follow a brand or company on Facebook or Twitter). In order to persuade people to follow them on social media, companies need to offer content that is relevant in the sense that it offers useful information, entertains, solves problems, offers customer service, or engages consumers with attractive content and conversations (van Noort & Willemsen, 2012).

Several correlational studies have shown positive associations between exposure to social media brand activity and attitudes towards the brand (Dijkmans, Kerkhof, & Beukeboom, 2015; Kim & Ko, 2012; Naylor, Lamberton, & West, 2012; Turri, Smith, & Kemp, 2013). Yet, the fact that exposure to corporate social media activity is, to a large degree, self-chosen raises the question whether these results reflect a positive effect of exposure on brand attitudes, or rather the reverse causal effect – that consumers who already have positive brand attitudes are more likely to choose to expose themselves to selected brand content. Although theoretically there are reasons to assume that exposure to interactive communication by companies helps foster a positive corporate reputation (Guillory & Sundar, 2013; Lee & Park, 2013), to our knowledge no longitudinal studies exist that have studied causal effects of social media brand exposure on corporate reputation over time.

Conversational Human Voice (CHV)

Compared to noninteractive media, a distinctive feature of social media is the opportunity to integrate a “human voice” (Kelleher, 2009) into social media platforms, which plays an important role in social media communications. According to Locke et al. (2001), companies should increasingly treat markets as “conversations” instead of “targets” in adapting to the demands of online consumers, and seeking collaboration with consumers is preferable to targeting them (Grunig, 2000). One way to motivate consumers to seek a continuing relationship with companies, is to exhibit not only competence but also humanness and warmth (Malone & Fiske, 2013), by communicating in a human style and incorporating a conversational human voice (CHV).

Kelleher (2009, p. 177) defined CHV as “an engaging and natural style of organizational communication as perceived by an organization's publics based on interactions between individuals in the organization and individuals in publics.” The concept of CHV was first mentioned by Locke et al. (2001), identifying a human voice as noticeable in online communications between organizations and the public, encouraged by participatory media. CHV stands in contrast to the formal “corporate voice”, where an organization speaks with one voice and with one identity, which is perceived as persuasive and profit-driven (Locke et al., 2001). According to Kelleher (2009), a company demonstrates a high level of CHV in its communications if it is open to dialogue, welcomes conversational communication, and provides prompt feedback, addressing criticism in a direct, but uncritical, manner. Furthermore, human voice characteristics also include communicating with a sense of humor, admitting mistakes, and treating others as human.

Several studies show that utilizing CHV plays an important role in how consumers evaluate companies and brands. Kelleher and Miller (2006) studied the impact of CHV on relational maintenance strategies by varying the style of personal communication in blogs, and then measured the extent to which a message actually conveys human communication attributes. CHV showed to be an important factor in improving relationships, and CHV correlated significantly with trust, satisfaction, control mutuality, and commitment in relationships (Kelleher & Miller, 2006). In a recent experimental study by Park and Lee (2013), the level of CHV was perceived to be higher for organizations' social media pages with a human presence than for those with a corporate presence. In this study, the human presence condition was operationalized by including a list of the first names of the employees on the organization's social networking page, and by exhibiting a personal approach through the use of those employees' names in postings. Moreover, utilizing a personal human voice when communicating online (i.e., evoking the perception that publics are conversing with a real person rather than with an anonymous company) led to higher user satisfaction ratings than impersonal communication. Thus, by employing CHV, a company can demonstrate that it isn't just a remote corporation that only produces and sells, but that there are 'real people' behind the scene that genuinely want to achieve customer satisfaction and meet the needs of the consumer.

Relatedly, in crisis communication, openness to conversations proved to be important in creating public engagement, leading to positive postcrisis perceptions (Sweetser & Metzgar, 2007; Yang, Kang, & Johnson, 2010). Negative brand evaluations caused by negative word of mouth can be attenuated by company webcare interventions, an effect which was mediated by perceptions of CHV (van Noort & Willemsen, 2012). Also, Sung and Kim (2014) showed that when an organization is both highly interactive and posts nonpromotional messages online, consumers report more positive attitudes towards this organization. In all these studies, dialogic communication and conversational human voice positively affected consumer evaluation of a company.

Recent research on parasocial interaction in online environments also points at the importance of communication in a human-like way for establishing a relationship with consumers. Parasocial interaction was described by Horton and Wohl (1956; see also Hartmann & Goldhoorn, 2011) as the experience of being in interaction with a TV performer, even without being in an actual interaction. A study by Colliander and Dahlen (2011) showed that (fashion) blogs – compared to online magazines – generated more positive brand attitudes and higher purchase intentions, because the more personal style of the blog lead readers to experience a higher level of parasocial interaction and to consider the blogger as a “friend” after repeated exposure to the blog. Labrecque (2014) demonstrated that companies can create a sense of parasocial interaction through messages that include elements indicating that the company shows human-like behavior, by listening and responding to consumers.

A crucial question, however, that has hitherto not been studied extensively, is whether consumers' exposure to a company's social media activities is affected by employing CHV as a company, and whether – over time – this results in a beneficial effect on corporate reputation. Based on our literature review, we hypothesize that conversational human voice mediates the effect of exposure to a company's social media activities on consumers' perceived corporate reputation.

Method

A two-wave longitudinal study was conducted among customers and noncustomers of KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, a Netherlands based international airline company. In a recent study of Socialbakers (2014), the airline industry was proclaimed as the most “socially devoted” business sector. Companies in this sector are among the most active in the use of social media (Hvass & Munar, 2012). Within this sector, KLM was the most socially devoted brand worldwide (Socialbakers, 2014). KLM is well-known in The Netherlands with a brand awareness of more than 90% (NBTC-NIPO Research, 2011), and is active “24/7” in 9 different languages on a broad range of online platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Google+, YouTube, Instagram). Every week, KLM has 30,000 social media interactions with consumers (Seel, 2014). KLM targets both customers and noncustomers with its online activities, and is widely recognized for its state-of-the-art social media activities and innovations – like introducing payment via Facebook and Twitter for extra services, and displaying live response times for answering via social media.

Participants

The data collection consisted of a two-wave longitudinal survey, with a one-year interval. In order to ensure a varied sample in terms of general social media usage intensity, exposure to the company's social media activities, and familiarity with KLM and its services, we determined the sample size and composition in advance. The participants – all residing in The Netherlands – were selected in three different ways, resulting in the following subsamples: (a) a sample representative for the (adult) Dutch population from the panel of the market research firm Motivaction (nt1 = 2077; 59% of total Nt1, and nt2 = 1280; 65% of total Nt2), (b) a sample from members of KLM's loyalty program (nt1 = 974; 28% of total Nt1, and nt2 = 532; 27% of total Nt2), (c) a sample recruited through a post on KLM's Facebook and Twitter page (nt1 = 480; 13% of total Nt1, and nt2 = 158; 8% of total Nt2).

One year after the first wave, the 3531 first-wave respondents were invited by e-mail to participate again in the second wave, resulting in a rejoin rate of 56% (Nt2 = 1969). These 1969 two-wave respondents (40% female) are included in the sample used in this longitudinal study, with an age distribution of < 25 years: 6%, 25–35: 12%, 36–45: 20%, 46–55: 25% and > 55: 37%.

Procedure

In the first wave, a hyperlink in the invitation mail (Motivaction panel and KLM loyalty members) or on KLM's Facebook and Twitter page, directed participants to the online questionnaire. In the second wave, all participants received an e-mail with a hyperlink to the questionnaire. After receiving thanks for their interest and cooperation, the participants answered the survey questions, which were equal for the two waves. The questionnaire started with questions about perceived corporate reputation, followed by questions on perceived conversational human voice of the company, and items on level of exposure to the company's social media activities. Subsequently, the survey included measures that were not part of the present study (i.e., about respondent's offline media usage, customer satisfaction and net promoter score). Completion took about 8 to 10 minutes.

Measures

Corporate reputation

Our measure of corporate reputation perception was based upon the “Reputation Quotient” scale (Fombrun, Gardberg, & Sever, 2000) which has 6 dimensions (emotional appeal, products & services, vision & leadership, workplace environment, social & environmental responsibility, and financial performance), each using 3 items. Of the original series of 18 items, we modified 5 items in order to fit the company's specific situation. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the 18 statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”).

For each wave, we averaged the responses of the 18 items to create one index of perceived corporate reputation (t1: Cronbach's α = .94, M = 3.52, SD = .49; t2: Cronbach's α = .94, M = 3.50, SD = .49) with scores ranging from 1 to 5, where higher scores indicate a more positive perceived corporate reputation.

Conversational human voice

To measure the level of perceived conversational human voice, in both waves participants answered six items about (a) the company's willingness to converse, (b) its openness to dialogue, (c) its efforts to communicate in a human voice, (d) its attempts to be interesting in communication, (e) its attempts to be enjoyable in communication, and (f) its promptness of feedback addressing criticism with an open manner. These items were taken from the scale of Kelleher and Miller (2006), which consists of 11 items. Respondents answered on a 5-point scale (ranging from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”). In order to limit the time needed to fill in the questionnaire, we had to reduce the number of questionnaire items for CHV. We selected the four (out of five) items with the highest factor loading on CHV from the study of Kelleher and Miller (2006) (i.e., items (a) to (d)), supplemented with two items that were the most relevant for other purposes of this broader research (i.e., items (e) and (f)). We averaged the six items for each wave separately to calculate a measure for CHV (t1: Cronbach's α = .89, M = 3.29, SD = .56; t2: Cronbach's α = .88, M = 3.31, SD = .55) ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating a higher perceived CHV.

Exposure to company's social media activities

In our structural equation model using latent variables, we determined consumers' exposure to company's social media activities from consumer's familiarity with the company's social media activities, and the online following of these activities on Facebook and/or Twitter. Concerning the familiarity with KLM's social media activities, we asked participants to what extent they were familiar with the company's social media activities on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = “Not familiar” (65% of Nt2), 2 = “Somewhat familiar” (21% of Nt2), 3 = “Familiar” (9% of Nt2), and 4 = “Very familiar” (5% of Nt2). With regard to following KLM on social media sites, we asked respondents who were at least “somewhat familiar” with the company's social media activities “On which social networking sites do you follow KLM?”1, where respondents were assigned a score “0” for following the company neither on Facebook nor on Twitter or for not being familiar with the company's social media activities (84% of Nt2), “1” for following on Facebook or Twitter (12% of Nt2), and “2” for following on Facebook and Twitter (4% of Nt2). Subsequently, familiarity with, and following of the company's social media activities were used – as described above – as estimators of the latent variable “exposure to company's social media activities.”

Results

To test our hypothesis on the mediating role of CHV in the association of consumers' social media exposure and corporate reputation, we conducted a longitudinal mediation analysis using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) on the dataset of the two waves. That is, we investigated whether consumers' social media exposure at the first wave has a longitudinal effect on corporate reputation measured in the second wave, and whether this is mediated by CHV.

Before conducting our main analysis, we first examined means, standard deviations and correlations for social media exposure, CHV and Reputation at t1 and t2 (see Table 1). The correlations between the same variables measured at t1 and t2 were high, as could be expected. CHV and Reputation were strongly positively related within both waves, with rt1 = .70 and rt2 = .69. Social media exposure showed, within both waves, a moderately positive association with CHV (rt1 = .30; rt2 = .33) and with Reputation (rt1 = .26; rt2 = .25). Looking at the correlations across t1 and t2, we found strong correlations between CHV and Reputation. CHVt1 and Reputationt2 showed a correlation of .51, and .53 between CHVt2 and Reputationt1. The correlations across t1 and t2 of Exposure with CHV, and of Exposure with Reputation were consistently found to be moderately positive, between .20 and .30. Overall, within and across waves, the highest correlation coefficients were found between CHV and Reputation of .51 and above, as a first signal for their relatedness.

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson's Correlations Between Observed Variables

| . | Descriptives . | Pearson's Correlations** . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Scale min. . | Scale max. . | Mean . | SD . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

| t1 variables | ||||||||||

| (1) Social media exposure | – | |||||||||

| (2) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.29 | .56 | .30 | – | ||||

| (3) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.52 | .49 | .26 | .70 | – | |||

| t2 variables | ||||||||||

| (4) Social media exposure | .72 | .28 | .25 | – | ||||||

| (5) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.31 | .55 | .28 | .58 | .53 | .33 | – | |

| (6) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.50 | .49 | .21 | .51 | .70 | .25 | .69 | – |

| . | Descriptives . | Pearson's Correlations** . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Scale min. . | Scale max. . | Mean . | SD . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

| t1 variables | ||||||||||

| (1) Social media exposure | – | |||||||||

| (2) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.29 | .56 | .30 | – | ||||

| (3) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.52 | .49 | .26 | .70 | – | |||

| t2 variables | ||||||||||

| (4) Social media exposure | .72 | .28 | .25 | – | ||||||

| (5) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.31 | .55 | .28 | .58 | .53 | .33 | – | |

| (6) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.50 | .49 | .21 | .51 | .70 | .25 | .69 | – |

Note: t1 = time 1; t2 = time 2; time interval is 1 year. N = 1969.

All correlations p < .01

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson's Correlations Between Observed Variables

| . | Descriptives . | Pearson's Correlations** . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Scale min. . | Scale max. . | Mean . | SD . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

| t1 variables | ||||||||||

| (1) Social media exposure | – | |||||||||

| (2) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.29 | .56 | .30 | – | ||||

| (3) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.52 | .49 | .26 | .70 | – | |||

| t2 variables | ||||||||||

| (4) Social media exposure | .72 | .28 | .25 | – | ||||||

| (5) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.31 | .55 | .28 | .58 | .53 | .33 | – | |

| (6) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.50 | .49 | .21 | .51 | .70 | .25 | .69 | – |

| . | Descriptives . | Pearson's Correlations** . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | Scale min. . | Scale max. . | Mean . | SD . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

| t1 variables | ||||||||||

| (1) Social media exposure | – | |||||||||

| (2) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.29 | .56 | .30 | – | ||||

| (3) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.52 | .49 | .26 | .70 | – | |||

| t2 variables | ||||||||||

| (4) Social media exposure | .72 | .28 | .25 | – | ||||||

| (5) Conversational human voice | 1 | 5 | 3.31 | .55 | .28 | .58 | .53 | .33 | – | |

| (6) Corporate reputation | 1 | 5 | 3.50 | .49 | .21 | .51 | .70 | .25 | .69 | – |

Note: t1 = time 1; t2 = time 2; time interval is 1 year. N = 1969.

All correlations p < .01

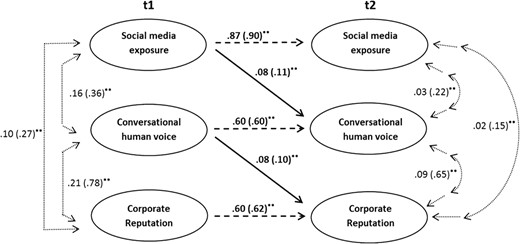

The purpose of our study was to perform a longitudinal test of mediation to determine the relations in our conceptual longitudinal model (Figure 1). We followed Cole and Maxwell's (2003) suggestions for longitudinal mediation with two time points, using structural equation modeling with latent variables. In this analysis, mediation is tested using two-wave longitudinal data while controlling for the initial levels of the constructs over time. This method is considered as an optimal test of mediation with two time points (see e.g., Praskova et al. (2014) for a recent application of this approach).

Conceptual longitudinal model, with relations between social media exposure, conversational human voice (CHV) and corporate reputation Note.**p < .01; t1 = time 1, t2 = time 2. Single-headed arrows in the middle indicate estimates for significant paths (solid arrows for cross-time paths, dashed arrows for autoregressive paths) with standardized results in parentheses. Double-headed dotted arrows on the left indicate correlations between latent variables, and on the right correlations between errors.

An assumption in this procedure is stationarity (Kenny, 1979), which implies that “the degree to which one set of variables produces change in another set remains the same over time.” (Cole & Maxwell, 2003, p. 560). In two-wave longitudinal studies – as compared to three or more waves – the stationarity assumption is necessary to investigate the longitudinal associations. Thus, in the Cole and Maxwell (2003) procedure it is assumed that the effect of CHV on reputation is constant over time, allowing for a test of longitudinal mediation in our two-wave panel data instead of three waves.

In sum, this test allowed us to examine whether (1) Exposuret1 predicted CHVt2, and (2) whether CHVt1 predicted Reputationt2 – above and beyond the autoregressive effects (i.e., paths predicting a latent construct from its prior level). As depicted in Figure 1, included in the longitudinal model were (a) the autoregressive paths (displayed as dashed arrows), (b) the cross-time paths (i.e., from Exposuret1 to CHVt2 and from CHVt1 to Reputationt2 – shown as solid arrows), and (c) correlations among the three latent constructs within t1 and within t2 (dotted arrows). The Mplus statistical software version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) was used to estimate the model.

To conduct the longitudinal mediation analysis using SEM, we created parcels for each of the three concepts to estimate the latent variables (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Parceling is a measurement practice that is often used in multivariate analyses, notably with latent-variable analysis techniques. According to Little et al. (2002, p. 152), a parcel can be defined as “an aggregate-level indicator comprised of the sum (or average) of two or more items, responses, or behaviors.” For perceived corporate reputation we used six parcels (i.e., the six reputation dimensions of the “Reputation Quotient” scale of Fombrun and Gardberg (2000)) of three items each as indicators for the latent variable. To estimate the latent variable social media exposure, we used – as set out in the Measures section – familiarity with the company's social media activities and online following of the company on Facebook and/or Twitter as indicators. For CHV, preliminary factor analyses revealed that the six item scores reflected a single underlying dimension. For both the t1 and the t2 wave, we found one dominant factor with a pre-extraction eigenvalue of 3.85, accounting for 64% of the variance. For parceling, there should be at least two items in a parcel (Little et al., 2002). To effectuate this, we created two parcels of three items each, since this renders a balanced distribution of items across parcels (see e.g., Hoyt et al. (2005) for a similar application of parceling). Based on the equivalence of the factor loadings in our preliminary factor analyses, we decided on which three items would be included in each of the two parcels. Additionally, we also tested four other models with different combinations of three items per parcel. The results in these alternative analyses were identical to the results we report in this paper. All indicators of the three latent variables loaded significantly on their respective constructs (see Table 2).

Estimated Parameters for Social Media Exposure, Conversational Human Voice and Corporate Reputation, for Longitudinal Mediation Model as seen in Figure 1

| . | Unstandardized loading t1 . | SE . | Standardized loading t1/t2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social media exposure | |||

| –Familiarity with company's social media activities | 1.00 | .00 | .95/.88 |

| – Following the company on Facebook and/or Twitter | .57 | .03 | .82/.83 |

| Conversational human voice | |||

| – Parcel 1 | 1.00 | .00 | .93/.94 |

| – Parcel 2 | .88 | .02 | .86/.85 |

| Corporate reputation | |||

| – Vision & leadership | 1.00 | .00 | .84/.84 |

| – Financial performance | .90 | .02 | .74/.72 |

| – Products & services | 1.10 | .03 | .88/.85 |

| – Workplace environment | .91 | .03 | .81/.82 |

| – Corporate social responsibility | 1.00 | .03 | .80/.78 |

| – Emotional appeal | 1.12 | .04 | .78/.76 |

| . | Unstandardized loading t1 . | SE . | Standardized loading t1/t2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social media exposure | |||

| –Familiarity with company's social media activities | 1.00 | .00 | .95/.88 |

| – Following the company on Facebook and/or Twitter | .57 | .03 | .82/.83 |

| Conversational human voice | |||

| – Parcel 1 | 1.00 | .00 | .93/.94 |

| – Parcel 2 | .88 | .02 | .86/.85 |

| Corporate reputation | |||

| – Vision & leadership | 1.00 | .00 | .84/.84 |

| – Financial performance | .90 | .02 | .74/.72 |

| – Products & services | 1.10 | .03 | .88/.85 |

| – Workplace environment | .91 | .03 | .81/.82 |

| – Corporate social responsibility | 1.00 | .03 | .80/.78 |

| – Emotional appeal | 1.12 | .04 | .78/.76 |

Note. t1 = time 1; t2 = time 2. All loadings p < .01

Estimated Parameters for Social Media Exposure, Conversational Human Voice and Corporate Reputation, for Longitudinal Mediation Model as seen in Figure 1

| . | Unstandardized loading t1 . | SE . | Standardized loading t1/t2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social media exposure | |||

| –Familiarity with company's social media activities | 1.00 | .00 | .95/.88 |

| – Following the company on Facebook and/or Twitter | .57 | .03 | .82/.83 |

| Conversational human voice | |||

| – Parcel 1 | 1.00 | .00 | .93/.94 |

| – Parcel 2 | .88 | .02 | .86/.85 |

| Corporate reputation | |||

| – Vision & leadership | 1.00 | .00 | .84/.84 |

| – Financial performance | .90 | .02 | .74/.72 |

| – Products & services | 1.10 | .03 | .88/.85 |

| – Workplace environment | .91 | .03 | .81/.82 |

| – Corporate social responsibility | 1.00 | .03 | .80/.78 |

| – Emotional appeal | 1.12 | .04 | .78/.76 |

| . | Unstandardized loading t1 . | SE . | Standardized loading t1/t2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social media exposure | |||

| –Familiarity with company's social media activities | 1.00 | .00 | .95/.88 |

| – Following the company on Facebook and/or Twitter | .57 | .03 | .82/.83 |

| Conversational human voice | |||

| – Parcel 1 | 1.00 | .00 | .93/.94 |

| – Parcel 2 | .88 | .02 | .86/.85 |

| Corporate reputation | |||

| – Vision & leadership | 1.00 | .00 | .84/.84 |

| – Financial performance | .90 | .02 | .74/.72 |

| – Products & services | 1.10 | .03 | .88/.85 |

| – Workplace environment | .91 | .03 | .81/.82 |

| – Corporate social responsibility | 1.00 | .03 | .80/.78 |

| – Emotional appeal | 1.12 | .04 | .78/.76 |

Note. t1 = time 1; t2 = time 2. All loadings p < .01

We first examined the correlations among the three latent constructs to check whether these correlations were in line with the correlation values for the measured constructs. This proved to be the case. CHV and reputation were positively correlated, rs = .78 and .72 for t1 and t2, respectively. Between CHV and social media exposure we found a moderate association for t1 and t2 of rs = .36 and .37. Lastly, the findings also showed weak positive correlations between social media exposure and reputation, rs = .27 and .23 for t1 and t2, respectively.

Subsequently, we conducted our main analysis – the longitudinal mediation analysis with the latent constructs estimated from the parcels. In our model, the three latent variables were allowed to covary at t1, their error terms were associated to each other at t2, and the error terms of corresponding indicators of the latent variables were allowed to covary across time. The conceptual model (Figure 1) showed good fit with the data, χ2(149; N = 1969) = 1006.32, p < .01; comparative fit index (CFI) = .97, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .054 (90% confidence interval [CI] = .051 – .057). As can be seen in Figure 1, in this model CHVt2 was predicted by Exposuret1, and Reputationt2 was predicted by CHVt1, controlling for the initial level of the constructs. Both of the two cross-time paths as well as the three autoregressive paths were significant and positive. Both the paths from Exposuret1 → CHVt2 (b = .11, p < .01), and CHVt1 → Reputationt2 (b = .10, p < .01) are significant, which indicates partial mediation. In other words, over time, exposure to a company's social media activities affects the perceived level of CHV. Also, CHV affects the perception of corporate reputation. We also examined the total indirect effect (i.e., multiplication of path estimates), and found a significant estimate, b = .01, SE = .003, p < .01. This confirmed our hypothesis that, over time, exposure to a company's social media activities, mediated by CHV, leads to a higher perception of corporate reputation. Overall, our model in Figure 1 explained 50% of the variance (R2) of Reputationt2.

Conclusion and Discussion

In this two-wave study among almost 2000 respondents, we sought empirical longitudinal evidence that consumers' exposure to the social media activities of a company affects the perceived level of CHV of a company, and that this positively influences the perception of a company's reputation. Additional to earlier correlational research (e.g., Dijkmans et al., 2015; Kim & Ko, 2012; Naylor et al., 2012; Turri et al., 2013), the findings of the present study are, to our knowledge, the first to suggest a causal relationship between these concepts. That is, in this study we demonstrate the positive reputational effect of consumers' exposure to a company's social media activities, and the mediating role of CHV in this relation.

With regard to traditional offline media (e.g., television, newspapers), previous research (Meijer & Kleinnijenhuis, 2006) already showed that exposure to news with a positive tone of voice about a company is associated with a more positive perception of corporate reputation. Concerning social media, a distinction can be made between (a) exposure to electronic word of mouth (eWOM) – the online positive and negative statements of consumers about a company (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004) – and (b) exposure to a company's activities via its own social media pages (e.g., on Facebook, Twitter). Relating to exposure to eWOM about a company, this showed to be beneficial for its reputation. Regarding exposure to a company's own social media activities, in the present study we showed the positive effects of exposure to these activities on perception of corporate reputation. This is an important finding, particularly following recent discussions where the added value of organizational social media use was called into question (Valentini, 2015). Corporate reputation plays an important role in the achievement of business objectives (Fombrun, Gardberg, & Sever, 2000). Thus, as a company, being able to improve perception of corporate reputation by employing social media activities and gaining exposure for these activities has scholarly as well as managerial relevance. Moreover, with its social media activities, a company can evoke positive eWOM, which can further strengthen its reputation.

A second main finding of this study was that CHV mediates the relation between consumers' level of exposure to company social media activities and perception of corporate reputation. Although social media are well-suited for online interactions with consumers, it also sets demands for companies. Compared to traditional media, a different kind of communication by companies can be observed on social media. Companies try to “humanize” their brands, and try to create an open perception that will invite consumers to connect and engage (Malone & Fiske, 2013). Earlier research has indicated that higher trustworthiness, commitment and satisfaction are among the consequences of experiencing CHV (Kelleher & Miller, 2006) – concepts that are also related to corporate reputation (Fombrun, Gardberg, & Sever, 2000). This suggests that to enhance perception of corporate reputation, using CHV in online company communication is of growing importance – for a number of reasons.

A first reason may be that a high level of CHV in social media activities fosters dialogic relationships (Kent & Taylor, 1998), which are effective in building dynamic and enduring relations with consumers. These relationships facilitate the exchange of ideas and opinions, and provide an opportunity for open conversations. In today's social media environments, consumers increasingly expect to be able to share their ideas and opinions with a company in human style interactions. The absence of CHV may become more striking to consumers than the presence of it. In that sense, from a satisfier, CHV might transform into a dissatisfier if not present. Companies should take this growing conventionality of CHV into account when addressing the publics on social media.

Second, employing CHV creates interactivity in communications, which may have positive relational consequences. For example, Saffer et al. (2013) showed that an organization's level of interactivity on Twitter positively influenced the company-consumer relationship quality. Furthermore, interactivity was shown to positively influence attitudes toward the company, perceived company credibility, and organization reputation (Guillory & Sundar, 2013; Li & Li, 2014). High-contingent message interactivity (Sundar et al., 2003) predicted a more positive organizational reputation (Lee & Park, 2013) and enhanced attitudinal outcomes (Sundar, Bellur, Oh, Jia, & Kim, 2014) compared to low-contingent message interactivity.

As a third reason, by communicating with CHV, a virtual online company-consumer relation may be evaluated more easily as a “real life” relation by consumers. This builds on the concepts of social presence (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976) and parasocial interaction (Horton & Wohl, 1956). Following studies on these concepts (Colliander & Dahlen, 2011; Labrecque, 2014), the impact of (online) communications depends on the degree to which the counterparty in a mediated communication environment is perceived as a “real” person. Interactivity and openness help to build feelings of parasocial interaction (Labrecque, 2014). Although we did not explicitly test this, our results suggest that actual interaction may not be necessary to develop feelings of parasocial interaction, and that instead passive exposure to a brand interacting with others in social media with a high CHV may be sufficient.

Although the consequences of a CHV are typically positive, recent studies have pointed at possible downsides of “anthropomorphized” brands (Aggarwal & McGill, 2007). When brands that are perceived as human face negative publicity caused by product missteps, this results in stronger negative consumers' brand evaluations than in the case of non-anthropomorphized brands (Puzakova, Kwak, & Rocereto, 2013). Aggarwal and McGill (2012) showed that the effects of brand humanization were also dependent on whether the anthropomorphized brand was perceived as a “partner” (i.e., cooperating with the consumer to reach a common goal) or as a “servant” (i.e., merely serving the consumer to reach his goal). Thus, the type and nature of CHV may affect the perceived character of the brand, resulting in different relational outcomes. We recommend further research to shed light on this issue.

As with all studies, this research also has its limitations. We deliberately chose a brand, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, that is highly active in social media, and is indeed one of the most interactive brands worldwide. In that sense, KLM may not be representative for the average company, especially because this study is mainly based on participants residing in KLM's home market. This limits the generalizability of the results, and we expect to find less pronounced reputation effects of social media exposure for companies that are less (inter)active in social media.

Second, in this study the conceptualization of social media exposure was based on two dimensions: familiarity with a company's social media activities and following those activities on Twitter and/or Facebook. Although these are important dimensions of exposure, measurement of this concept could be more elaborate. In order to more fully investigate the impact of exposure to a company's social media activities on corporate reputation, future research should include a broader range of social media exposure measures, and distinguish between passive exposure (e.g., respondents' visiting frequency of a company's social media pages, the time spent on these pages), and active participation (e.g., respondents' frequency or nature of interaction with the company).

Third, perceived CHV is a general measure, which does not specifically refer to merely social media communications. It is thus possible that the perceived level of the company's CHV was influenced by observed communications in other media, such as traditional media, the company website, or the corporate blog.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to a better understanding of the relationship between consumers' exposure to a company's social media activities, level of perceived CHV and corporate reputation. We showed that, over time, consumers' exposure to company social media activities positively affects perception of corporate reputation. Moreover, we showed that CHV is an important factor in this relation – CHV can reinforce the effects of social media exposure. The findings provide evidence that for companies employing social media activities and optimizing their effectiveness, indeed “human-style conversations lead to better reputations.”

Note

In the first wave of our study, besides asking on which social networking sites participants followed KLM, in the same question participants were asked for their appreciation of KLM's activities on each social network site (following and appreciation were combined in one drop down menu with 1–10 = appreciation low-high, 11 = “I do not follow KLM on this site”). Because of an error in the drop down menu, not all respondents saw the answer option indicating 11 = “I do not follow KLM on this site”. The results show a high percentage with a very negative appreciation of KLM's social media activities (score of 1 – for Facebook: 10%, for Twitter: 20%). Since, as a result, the distribution strongly deviates from the expected normal distribution and from the results in the second wave, we considered it likely that the “1”-option was used to indicate being a non-follower, and we decided to consider respondents in the “1”-category as non-followers. In the second wave, we corrected this item in the questionnaire. Importantly, inclusion or exclusion of the “1”-scores in the first wave as followers did not in any way affect the results we report in this paper.

References

About the Authors

Corné Dijkmans, M.Sc. ([email protected]), is a researcher and senior lecturer of Online Marketing & New Media at NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands, and is currently taking his Ph.D. as an external researcher at the Department of Communication Science at VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands. His research is focused on the effects of social media use of organizations on consumers. Address: NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences, P.O. Box 3917, 4800 DX Breda, The Netherlands.

Peter Kerkhof, Ph.D. ([email protected]), currently holds the chair in social media at the Department of Communication Science, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands. His recent research interests focus on the uses of social media by consumers and companies, and on the conversations that they engage in on social media.

Asuman Büyükcan-Tetik, M.Sc. ([email protected]), is a researcher and Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Clinical Child and Family Studies, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Her research interests are interpersonal relationships, self-control, and trust.

Camiel J. Beukeboom, Ph.D. ([email protected]), is an assistant professor at the Department of Communication Science at VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands. His main interests are in (mediated) Interpersonal Communication. His research focuses on (biased) language use and the use and effects of social media in interpersonal and corporate communication.

Author notes

Correction made after online publication August 18, 2015: The Editorial Record has been updated.