-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Wouter van der Schors, Marco Varkevisser, Does Enforcement of the Cartel Prohibition in Healthcare Reflect Public and Political Attitudes Towards Competition? A Longitudinal Study From the Netherlands, Journal of Competition Law & Economics, Volume 19, Issue 2, June 2023, Pages 193–219, https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhad001

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In market-based healthcare systems, due to the high and increasing degree of integration between healthcare providers and purchasers, the enforcement of the cartel prohibition is both important and ever more complex. Competition authorities operate independently, but their approach to enforcement may be influenced by the public and political context. Within the setting of the Dutch healthcare system, we study how the cartel prohibition was enforced between 2004 and 2020 and focus on whether a relationship with public and political attitudes towards competition in healthcare can be observed. Using both qualitative and sentiment analyses, we assessed 38 formal and informal documents issued by the competition authority, 126 written parliamentary questions and almost 1,500 newspaper articles. Our findings reveal that during the first half of the study period (2004–2012), ex-post punitive formal enforcement of violations of the cartel prohibition, such as market-sharing and price-fixing agreements, predominated. During the second half of the study period (2012–2020); however, the competition authority’s focus seems to have shifted toward providing ex-ante informal guidance. We clearly observe negative public and political attitudes towards competition in healthcare as well as a distinct shift in enforcement of the cartel prohibition in Dutch health care. However, we are not able to test for a causal relationship between both observations.

I. INTRODUCTION

Inter-organizational collaboration (IOC) between healthcare providers plays a pivotal and increasingly prominent role in health systems globally (Palumbo et al., 2020). Although the definition of an IOC can vary substantially, they can broadly be described as formal arrangements whereby two or more independent organizations work together by integrating some—but not all—of their activities (Löfström, 2009). These IOCs are established to achieve economies of scale, improve quality of care (Baker et al., 2015), cope with increasing or changing demand (Yarbrough and Powers, 2006), meet budgetary constraints (Mervyn et al., 2019), provide joint service delivery (Bunger et al., 2014) or work towards integrated care delivery (Lyngsø et al., 2016; Valentijn, 2016), to name just a few examples. In general, IOC is regarded as an important route by which to achieve broader healthcare objectives such as accessibility, affordability, and quality. In addition to bottom-up initiatives, IOCs are increasingly being supported by health policy and financed by third-party payers (Field et al., 2020; Pettigrew et al., 2019; VWS, 2018).

However, in systems organized around the market-based allocation of resources in the healthcare system, IOCs may infringe competition legislation if the partners involved are also competitors, and they could lead to exclusion in nonhorizontal relationships between providers from different sectors. In market-based healthcare systems, competition policy and its enforcement by National Competition Authorities (NCAs) can be regarded as a vital precondition for achieving public goals like accessibility, affordability and quality of care (Loozen, 2015). In practice; however, competition enforcement in healthcare often diverges from that in other sectors, particularly due to political sensitivities around solidarity (Guy, 2021). Furthermore, competition in healthcare systems generally lacks widespread public support (Gaynor, 2006; Loozen, 2015). As a result, there is widespread discussion of making changes to the general rules on competition when it comes to healthcare specifically. Competition authorities may also be more susceptible to external public and political pressure (Sauter, 2011) and negative public perceptions around the role of competition in healthcare could also affect the evaluation of evidence by the courts (Gaynor, 2006). Business organizations may also exert pressure on political actors or competition authorities to restrict competition to favour their own interests, or they may exploit prevailing public attitudes to achieve this same goal (Guidi, 2012; Van Damme, 2020). This may have an attenuating effect on competition authority decision-making.

In theory, NCAs are strictly independent and autonomous. However, in practice the competition enforcement is subject to a considerable degree of interpretation, and may be affected by political or public pressure. For instance, during the great financial crisis of 2007–2008, competition authorities were put under pressure by member states to ignore the abuse by dominant firms and take a permissive attitude towards state aid (Reynolds et al., 2009). More recently, corporate lobbies request a less strict competition law enforcement to accommodate potentially anticompetitive agreements aimed at tackling climate change (Schinkel and Treuren, 2021). Several examples suggest that public and political attitudes can affect NCA decision-making in practice (Guidi, 2012; Kovacic, 2014). Most of these examples are in the field of merger control (van de Gronden and de Vries, 2006).1 With regard to cartel prohibition cases, direct interference seems less common and examples are more subtle. In the Netherlands, however, dissatisfaction with competition authority decision-making in the field of healthcare is evident in both public and political attitudes. For instance, the Dutch competition authority’s decision (ACM) in 2011 to fine the national GP association (LHV) for restrictions to entry was fiercely debated and resulted in political opposition, as expressed in parliamentary questions (Schut and Varkevisser, 2017). A few years later, political pressure forced the ACM to allow more leeway for collaboration among GPs (Maarse and Jeurissen, 2019). So it seems that the complex field in which competition authorities operate when it comes to enforcing competition rules in healthcare can have an impact on its interpretation and application of the general competition rules.

In this paper, we will explore the enforcement of competition rules in the context of (changing) public and political attitudes towards competition and collaboration in healthcare. The Dutch healthcare system is particularly suitable for this because it is based on the principles of regulated competition and thus requires strict antitrust enforcement (Loozen, 2015). It can be regarded as a forerunner in the liberalisation of healthcare markets (Sauter, 2010). At the same time, however, the benefits of collaboration among providers are increasingly recognized, which may require less strict competition policy. Here, we will address the ambiguous role of competition enforcement in health care by answering two research questions:

RQ1: How were competition rules around collaboration enforced in the healthcare sector in the Netherlands in the period 2004–2020?

RQ2: To what extent does competition enforcement in Dutch healthcare reflect public and political attitudes towards the role of competition in this sector?

This paper’s intended contribution to the literature is twofold. First, a number of studies have examined the application of the cartel prohibition in Dutch healthcare (Guy, 2019; Loozen, 2015; Sauter, 2014; Schut and Varkevisser, 2017; Van der Schors et al., 2020). Nonetheless, in contrast to merger activities, no studies have investigated both formal and informal competition policy documentation on collaborations in a systematic and integrated manner. Such insight is urgently needed, however, because of the increasing number of IOCs in the current health system. More importantly, collaboration does not require ex-ante approval, and the possibility for an ex-ante exemption by ACM has been abolished (Jansen, 2013). As collaboration includes a wide range of different types of integration that stop short of a merger, insight into the competition authority’s attitude towards various types of integration is of both academic and societal relevance. Both healthcare decision-makers and regulators could benefit from insight into the circumstances under which IOCs and regulated competition are compatible or matters of exclusion. Secondly, although some research has been carried out on attitudes towards competition in healthcare (de Vries et al., 2021; Dijkstra and van Stekelenburg, 2021), the association between these attitudes and the application of cartel prohibition in the healthcare sector has not previously been researched. Since our longitudinal study uses newspaper articles and parliamentary questions that span an eight-year period, it provides a comprehensive insight into the prevailing public and political attitudes on competition in healthcare.

A. Study Setting

The study was conducted in the context of the market-based Dutch healthcare system. The combination of regulated competition and a strong tendency towards more IOCs provides a unique setting in which to explore the challenges of competition enforcement in healthcare (Enthoven and Van De Ven, 2007; Sauter, 2014; Van der Schors et al., 2021). In 2006, a major reform to the Dutch healthcare system took place, which can best be regarded as the endpoint of a series of small and incremental policy and institutional adjustments that included a couple of key moments (Bertens and Vonk, 2020; Helderman et al., 2005). The year 2006 marked the culmination of those reforms in the form of the introduction of two laws. Firstly, the Health Insurance Act (ZVW), which makes it mandatory for all residents of the Netherlands to purchase basic health insurance; secondly, the Health Care Market Regulation Act (WMG), which regulates the development, regulation and supervision of healthcare markets as well as the protection of patients’ interests (Maarse et al., 2016). The market-oriented reform resulted in greater choice both for the competing health insurers, which as purchasers of healthcare are expected to (selectively) contract services from providers, and for patients who are entitled to choose any insurer as well as any healthcare provider that best suits their needs.

In the healthcare sector, as in all other markets featuring competition, responsibility for antitrust enforcement is exercised by the Dutch Authority for Consumers & Markets (ACM).2 Legislation on collaborations is set out in Article 6(1) of the Competition Act, which is based largely on its European counterpart; that is, Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Collaboration between organizations is therefore prohibited if its goal is anticompetitive or if it leads to anticompetitive conduct or outcomes (Loozen, 2015). Examples of (hard-core) anticompetitive conduct include market-sharing, price-setting, boycotts and the exchange of competition-sensitive information with the aim of restricting competition. The cartel prohibition is an ex-post enforcement tool that also applies to healthcare providers. As a result, before establishing an IOC, it is important for the collaborating organizations to check whether their intended collaboration falls under the scope of the cartel prohibition by means of a self-assessment. Where applicable, healthcare organizations need to prove that competition is not unnecessarily restricted by the collaboration, and that the benefits for patients outweigh any anticompetitive effects (Article 6(3)).

The ACM can draw on a broad range of formal and informal instruments. Punitive and nonpunitive formal instruments generally take the form of binding decisions, fines or cease and desist orders, and are aimed both at resolving noncompliance and having a deterrent effect. The ACM can also deploy alternative instruments to increase awareness and understanding of the application of competition law, and facilitate informed decision-making by market parties. A specific form of guidance is an informal opinion, which is a provisional, nonbinding informal assessment on whether a proposed form of collaboration is presumed to be permissible under the Competition Act. In the Netherlands, informal opinions can be issued at the request of the relevant parties when (1) the proposed arrangements have not yet been implemented and concern a new legal question, (2) when the issue is of economic or societal importance (3) and when enough information has been provided by the parties to form an informal opinion, without the need for the ACM to conduct its own in-depth study (ACM, 2019b).3

II. METHODS

A. Design

The aim of our study was to assess the enforcement of competition policy with respect to inter-organizational collaboration in Dutch healthcare in the light of prevailing public and political attitudes, and—perhaps changing—sentiments towards the role of competition in the healthcare system. To this end, we conducted text analyses using both inductive and deductive coding as well as a sentiment analysis. These methods enable many words of text to be condensed into fewer content categories. Our study design was therefore suited to analysing an extensive quantity of nonscientific or ‘grey’ literature in a systematic manner, allowing us to make comparisons over time without the risk of recall bias.

B. Data Sources

The research material consists of four sources (Table 1). Documentation provided by the ACM has been used to shed light on the competition policy perspective on collaborations. Articles from major newspapers and written parliamentary questions were used to develop a sense of the prevailing public and political attitudes towards competition in healthcare. Our study covers the period between 2004 and 2020. In 2004, the Dutch competition authority started antitrust enforcement in Dutch healthcare with the release of two position papers analysing competition in hospital markets and long-term markets. In 2020, we finished the systematic process of gathering data to be included in our research. as this was the last complete year for which data was fully available.

| Perspective . | Type . | Source . | Identified records . | Excluded . | Included in study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competition authority perspective | Formal and informal documentation | ACM.nl | 32 | N/A | 32 |

| Court rulings | Rechtspraak.nl | 6 | N/A | 6 | |

| Public perspective | Newspaper articles | Lexis (NRC Handelsblad, de Volkskrant, Trouw, De Telegraaf, Algemeen Dagblad) | 1715 | 5 (Duplicates) 247 (Not about Dutch healthcare) | 1463 |

| Political perspective | Parliamentary written questions | Officielebekendmakingen.nl | 342 | 127 (Duplicates) 89 (Written answers) | 126 |

| Perspective . | Type . | Source . | Identified records . | Excluded . | Included in study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competition authority perspective | Formal and informal documentation | ACM.nl | 32 | N/A | 32 |

| Court rulings | Rechtspraak.nl | 6 | N/A | 6 | |

| Public perspective | Newspaper articles | Lexis (NRC Handelsblad, de Volkskrant, Trouw, De Telegraaf, Algemeen Dagblad) | 1715 | 5 (Duplicates) 247 (Not about Dutch healthcare) | 1463 |

| Political perspective | Parliamentary written questions | Officielebekendmakingen.nl | 342 | 127 (Duplicates) 89 (Written answers) | 126 |

| Perspective . | Type . | Source . | Identified records . | Excluded . | Included in study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competition authority perspective | Formal and informal documentation | ACM.nl | 32 | N/A | 32 |

| Court rulings | Rechtspraak.nl | 6 | N/A | 6 | |

| Public perspective | Newspaper articles | Lexis (NRC Handelsblad, de Volkskrant, Trouw, De Telegraaf, Algemeen Dagblad) | 1715 | 5 (Duplicates) 247 (Not about Dutch healthcare) | 1463 |

| Political perspective | Parliamentary written questions | Officielebekendmakingen.nl | 342 | 127 (Duplicates) 89 (Written answers) | 126 |

| Perspective . | Type . | Source . | Identified records . | Excluded . | Included in study . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competition authority perspective | Formal and informal documentation | ACM.nl | 32 | N/A | 32 |

| Court rulings | Rechtspraak.nl | 6 | N/A | 6 | |

| Public perspective | Newspaper articles | Lexis (NRC Handelsblad, de Volkskrant, Trouw, De Telegraaf, Algemeen Dagblad) | 1715 | 5 (Duplicates) 247 (Not about Dutch healthcare) | 1463 |

| Political perspective | Parliamentary written questions | Officielebekendmakingen.nl | 342 | 127 (Duplicates) 89 (Written answers) | 126 |

First, the primary source of data is the documentation published about collaboration cases in healthcare on the ACM’s website. Emphasis was placed on documentation specifically focusing on actual cases of collaboration in healthcare. Hence, documentation offering general guidance was excluded, such as the three ACM generic guidelines published in 2003, 2007 and 2010. In total, 32 documents were eligible for inclusion. We distinguished between formal decisions and case law on the one hand (12 documents) and guidance and informal opinions on the other (19 documents). We also added six court rulings pertaining to appeals against formal decisions made by the ACM. These rulings were retrieved from www.rechtspraak.nl, the official website for the Dutch lawcourts where all court decisions can be accessed. In total, 38 documents were therefore included.

Second, Dutch newspaper articles were selected from NexisUni, a database containing all newspaper articles published in the Netherlands. The database was searched using the following search terms: healthcare “Gezondheidszorg” and competition “Marktwerking.” The five largest Dutch newspapers by readership were searched (NRC Handelsblad, de Volkskrant, Trouw, De Telegraaf and Algemeen Dagblad). These newspapers have a joint market share of 90 percent and cover a large share of the political spectrum (Veerbeek et al., 2022). These search results were narrowed down based on the title and abstract. Ultimately, 1,463 newspaper articles were selected for further analysis (Table 1).

Third, to capture (changes in) the prevailing political attitudes to competition in healthcare, parliamentary written questions were extracted from a Dutch government database containing all government publications (www.officielebekendmakingen.nl). These written questions were put to the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS) by members of parliament, and thus reflect the political concerns and considerations around the topic of competition in healthcare. The search string used was similar to the strategy applied to the newspaper articles.

C. Analyses

Our qualitative analyses included both deductive and inductive coding as well as sentiment analysis. The coding was done mainly by a team of two researchers, who independently assessed and analysed informal and formal documentation and parliamentary questions, after which they discussed their findings to limit subjective interpretations as much as possible. The quotations used in the text have been translated from Dutch to English. A specification of analysis method applied for each source has been explained below.

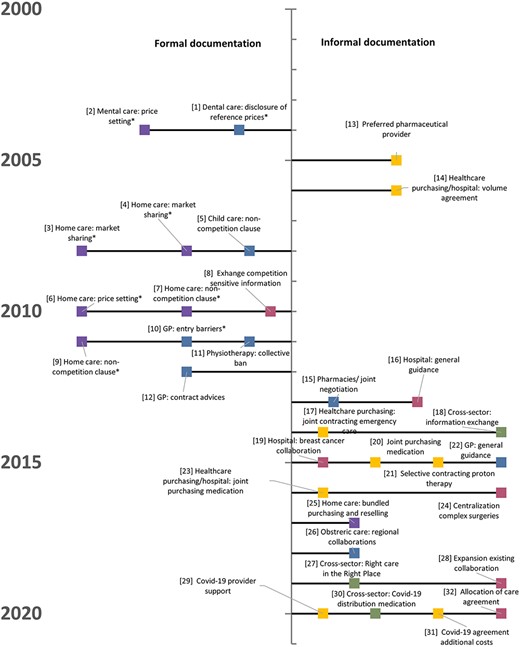

1. Competition Authority Documentation

Formal and informal documentation issued by the ACM was deductively coded. Codes were selected after a scientific and professional literature search on the topic and concerning the research framework. The codes used for the formal documentation included the year of publication, healthcare sectors involved, organizations involved, the conduct involved, the main reason(s) for collaboration by the healthcare organization, the opinion issued by ACM, and the sanction imposed and the appeal (when applicable). The codes for the informal documentation included: the year of publication, healthcare sector, type of collaboration, type of document, efficiencies cited (by the healthcare organization), risk of anticompetitive behaviour, and decision/advice (ACM). The Results section presents these findings in the form of a timeline showing all the documents issued, as well as overview tables for both types of documentation (Tables 2 and 4) and for the six court rulings (Table 3). The data was managed and analysed using Atlas.ti version 9.0.14.

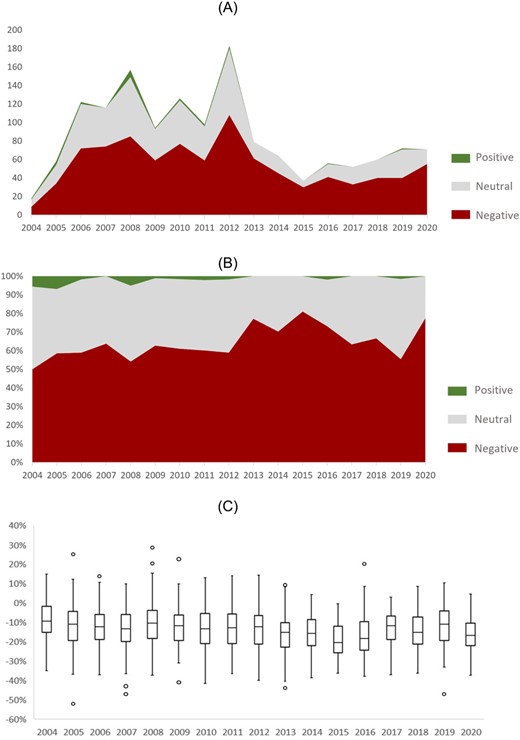

2. Newspaper Articles

The newspaper articles were analysed using SentiStrength, a sentiment analysis (‘opinion mining’) program. We conducted an analysis at the article level. Based on an extensive Dutch lexicon of almost 2,700 words or phrases known to express sentiment, SentiStrength identifies the presence of positive or negative words or combination of words in texts and assesses in which strength this sentiment is expressed (Thelwall et al., 2012). SentiStrength takes account of negating words, idioms and irony. The positive dimension ranges from 1 (neutral) to +5 (strongly positive). The negative dimension ranges from −1 (neutral) to −5 (strongly negative). The overall score for a text is calculated by adding all the sentence scores together and calculating the percentage difference between the negative and positive sentiments relative to the length of the article. These article-level percentages were categorized into a three-point scale: <−10 percent (negative), −10 to 10 percent (neutral), >10 percent (positive). A detailed step-by-step explanation of how these percentages were calculated can be found in Box 1, below.

Sentiment analysis in Sentistrength

1. All the articles were loaded into SentiStrength

2. SentiStrength automatically gave every sentence a score for the strongest positive emotion word and the strongest negative emotion word. The positive score ranged from 1 to 5, with 5 being the strongest positive score. The negative score ranged from −1 to −5, with −5 being the strongest negative score.

3. The strongest negative and positive scores from every sentence were combined and corrected for the absolute difference between two scores, leading to one percentage (left side of the equation below).

4. In SentiStrength, every sentence was also automatically given a score for the average positive sentiment per sentence and the average negative sentiment per sentence. The positive score ranged from 1 to 5, and the negative dimension ranged from −1 to −5.

6. The average negative and positive scores from every sentence were combined and corrected for the absolute difference between two scores, leading to one percentage (right side of the equation below).

7. The strongest and average percentages were combined and divided by 2.

|$\frac{\left(\frac{\left(\mathrm{Positive}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{str}\,+\,\mathrm{negative}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{str}\right)}{\left[\left(\mathrm{positive}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{str}\,-\,\mathrm{negative}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{str}\right)/2\right]}\right)+\left(\frac{\left(\mathrm{Positive}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{avg\,}+\,\mathrm{negative}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{avg}\right)}{\left[\left(\mathrm{positive}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{avg}\,-\,\mathrm{negative}\ \mathrm{dimension}\ \mathrm{avg}\right)/2\right]}\right)}{2}$|

8. This single percentage per article was categorized into a three-point scale: <−10% (negative), −10%; 10% (neutral), >10% (positive).

Example

For one particular article, Sentistrength produced a strongest score on the positive dimension of 26. The strongest score on the negative dimension was −29. When we put these numbers through the formula above, we get a percentage difference of −11% between the negative dimension and positive dimension. Sentistrength produced an average score of 22 for the positive dimension and an average score on the negative dimension of −27. When we put these numbers through the formula above, we get a percentage difference of −20% between the negative dimension and positive dimension. When these figures were combined and divided by two, the article level score was −16%. This number was then categorized into the three-point scale to facilitate interpretation and the article was qualified as negative.

Chronological overview of ACM’s formal (left) and informal documentation (right).

3. Written Parliamentary Questions

The short nature of the sentences, the lack of context and their formulation as questions meant that automated analysis in SentiStrength was not a suitable method for isolating the sentiments and would have led to biased results. Instead, political attitudes towards competition were extracted using manual inductive coding. Of the 342 parliamentary questions included in our analyses, duplicates and written answers were excluded (see Table 1). Subsequently, 126 sentences were inductively coded based on a two-step approach. Twenty randomly selected parliamentary questions were assessed to identify emerging themes and develop an inductive coding framework. Second, all the parliamentary questions were coded by the two researchers based on this framework.4 Missing codes were added to the coding framework during this process. Table 5 shows the inductive codes that emerged from the analysis, as well as the frequency and relative distribution of these codes in the data.

| Case number . | Year . | Healthcare sectors . | Involved organizations . | Conduct . | Main reason(s) for collaboration . | Opinion (ACM) . | Imposed sanction? . | Appeal? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2004 | Dental care | Representative association | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting dentists with price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fine: €400 k, cease and desist | No |

| [2] | 2004 | Mental care | Four representative associations | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting professionals with cost price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fines: €56 k, €70 k, €80 k and €240 k cease and desist | Yes, see [i] in Table 3 |

| [3] | 2008 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in province Noord-Holland | An agreement of geographical division of the market | Improve quality of care and realise neighbourhood-level care | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €800kand €4.003 m | Yes, see [ii] in Table 3 |

| [4] | 2008 | Home care | Three home care provider organizations in Province of Utrecht | Collaboration agreement on client referrals and specialization | Exchange of information, patients retain freedom of choice. | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €1.621 m, €816 k, €611 k | Yes, see [iii] in Table 3 |

| [5] | 2008 | Childcare | Five childcare organizations Amsterdam | Alliance on close collaboration | Organizations can positively differentiate their offering on quality, achieving synergy gains | Market sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: (1) no competition sensitive information to be exchanged and (2) entry plans for each other’s markets not to be shared. | No |

| [6] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Friesland | Collaboration on tender and price agreements | Conduct did not influence the market; patients retained freedom of choice. | Exchange of competition sensitive information the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €2.020 m and €314 k | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [7] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Overijssel | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Create a competitive position vis-à-vis nationwide competitors | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €4.348 m and €1.304 m | Yes, see [v] in Table 3 |

| [8] | 2010 | Hospital care | Ten hospitals in Province Noord-Holland | Exchanging medical registration and production data | Develop regional data collection | Exchange of competition-sensitive information | Binding commitment: (1) no competition-sensitive information to be exchanged (2) and other providers to have insight into information exchanged under the same conditions as partner hospitals | No |

| [9] | 2011 | Home care | Two home care providers in the Randstad region | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Improve negotiation power | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €3 m, €1.343 m | No, fines repealed by ACM after [ii] [iii] |

| [10] | 2011 | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Fine: €7.719 m, cease and desist to remove and withdraw entry recommendations. | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [11] | 2011 | Physiotherapy | Representative organization | Publication of an advice not to sign contracts with health insurers | Dispute between physiotherapists and health insurers | Potential of collective boycott | No, the association promised to comply with the competition act. | No |

| [12] | 2012 (see [10]) | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: The national GP Association and regional subdivisions promised, among other things: (1) not to interfere with contract negotiations (2) not to provide advice concerning contract signing or entry of new GPs. | |

| Case number . | Year . | Healthcare sectors . | Involved organizations . | Conduct . | Main reason(s) for collaboration . | Opinion (ACM) . | Imposed sanction? . | Appeal? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2004 | Dental care | Representative association | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting dentists with price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fine: €400 k, cease and desist | No |

| [2] | 2004 | Mental care | Four representative associations | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting professionals with cost price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fines: €56 k, €70 k, €80 k and €240 k cease and desist | Yes, see [i] in Table 3 |

| [3] | 2008 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in province Noord-Holland | An agreement of geographical division of the market | Improve quality of care and realise neighbourhood-level care | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €800kand €4.003 m | Yes, see [ii] in Table 3 |

| [4] | 2008 | Home care | Three home care provider organizations in Province of Utrecht | Collaboration agreement on client referrals and specialization | Exchange of information, patients retain freedom of choice. | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €1.621 m, €816 k, €611 k | Yes, see [iii] in Table 3 |

| [5] | 2008 | Childcare | Five childcare organizations Amsterdam | Alliance on close collaboration | Organizations can positively differentiate their offering on quality, achieving synergy gains | Market sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: (1) no competition sensitive information to be exchanged and (2) entry plans for each other’s markets not to be shared. | No |

| [6] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Friesland | Collaboration on tender and price agreements | Conduct did not influence the market; patients retained freedom of choice. | Exchange of competition sensitive information the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €2.020 m and €314 k | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [7] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Overijssel | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Create a competitive position vis-à-vis nationwide competitors | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €4.348 m and €1.304 m | Yes, see [v] in Table 3 |

| [8] | 2010 | Hospital care | Ten hospitals in Province Noord-Holland | Exchanging medical registration and production data | Develop regional data collection | Exchange of competition-sensitive information | Binding commitment: (1) no competition-sensitive information to be exchanged (2) and other providers to have insight into information exchanged under the same conditions as partner hospitals | No |

| [9] | 2011 | Home care | Two home care providers in the Randstad region | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Improve negotiation power | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €3 m, €1.343 m | No, fines repealed by ACM after [ii] [iii] |

| [10] | 2011 | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Fine: €7.719 m, cease and desist to remove and withdraw entry recommendations. | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [11] | 2011 | Physiotherapy | Representative organization | Publication of an advice not to sign contracts with health insurers | Dispute between physiotherapists and health insurers | Potential of collective boycott | No, the association promised to comply with the competition act. | No |

| [12] | 2012 (see [10]) | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: The national GP Association and regional subdivisions promised, among other things: (1) not to interfere with contract negotiations (2) not to provide advice concerning contract signing or entry of new GPs. | |

| Case number . | Year . | Healthcare sectors . | Involved organizations . | Conduct . | Main reason(s) for collaboration . | Opinion (ACM) . | Imposed sanction? . | Appeal? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2004 | Dental care | Representative association | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting dentists with price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fine: €400 k, cease and desist | No |

| [2] | 2004 | Mental care | Four representative associations | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting professionals with cost price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fines: €56 k, €70 k, €80 k and €240 k cease and desist | Yes, see [i] in Table 3 |

| [3] | 2008 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in province Noord-Holland | An agreement of geographical division of the market | Improve quality of care and realise neighbourhood-level care | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €800kand €4.003 m | Yes, see [ii] in Table 3 |

| [4] | 2008 | Home care | Three home care provider organizations in Province of Utrecht | Collaboration agreement on client referrals and specialization | Exchange of information, patients retain freedom of choice. | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €1.621 m, €816 k, €611 k | Yes, see [iii] in Table 3 |

| [5] | 2008 | Childcare | Five childcare organizations Amsterdam | Alliance on close collaboration | Organizations can positively differentiate their offering on quality, achieving synergy gains | Market sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: (1) no competition sensitive information to be exchanged and (2) entry plans for each other’s markets not to be shared. | No |

| [6] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Friesland | Collaboration on tender and price agreements | Conduct did not influence the market; patients retained freedom of choice. | Exchange of competition sensitive information the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €2.020 m and €314 k | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [7] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Overijssel | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Create a competitive position vis-à-vis nationwide competitors | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €4.348 m and €1.304 m | Yes, see [v] in Table 3 |

| [8] | 2010 | Hospital care | Ten hospitals in Province Noord-Holland | Exchanging medical registration and production data | Develop regional data collection | Exchange of competition-sensitive information | Binding commitment: (1) no competition-sensitive information to be exchanged (2) and other providers to have insight into information exchanged under the same conditions as partner hospitals | No |

| [9] | 2011 | Home care | Two home care providers in the Randstad region | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Improve negotiation power | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €3 m, €1.343 m | No, fines repealed by ACM after [ii] [iii] |

| [10] | 2011 | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Fine: €7.719 m, cease and desist to remove and withdraw entry recommendations. | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [11] | 2011 | Physiotherapy | Representative organization | Publication of an advice not to sign contracts with health insurers | Dispute between physiotherapists and health insurers | Potential of collective boycott | No, the association promised to comply with the competition act. | No |

| [12] | 2012 (see [10]) | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: The national GP Association and regional subdivisions promised, among other things: (1) not to interfere with contract negotiations (2) not to provide advice concerning contract signing or entry of new GPs. | |

| Case number . | Year . | Healthcare sectors . | Involved organizations . | Conduct . | Main reason(s) for collaboration . | Opinion (ACM) . | Imposed sanction? . | Appeal? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2004 | Dental care | Representative association | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting dentists with price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fine: €400 k, cease and desist | No |

| [2] | 2004 | Mental care | Four representative associations | The disclosure of reference prices on the website | Advisory prices with the aim of assisting professionals with cost price calculation | Anticompetitive restriction of (price) competition | Fines: €56 k, €70 k, €80 k and €240 k cease and desist | Yes, see [i] in Table 3 |

| [3] | 2008 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in province Noord-Holland | An agreement of geographical division of the market | Improve quality of care and realise neighbourhood-level care | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €800kand €4.003 m | Yes, see [ii] in Table 3 |

| [4] | 2008 | Home care | Three home care provider organizations in Province of Utrecht | Collaboration agreement on client referrals and specialization | Exchange of information, patients retain freedom of choice. | Market-sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €1.621 m, €816 k, €611 k | Yes, see [iii] in Table 3 |

| [5] | 2008 | Childcare | Five childcare organizations Amsterdam | Alliance on close collaboration | Organizations can positively differentiate their offering on quality, achieving synergy gains | Market sharing agreement with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: (1) no competition sensitive information to be exchanged and (2) entry plans for each other’s markets not to be shared. | No |

| [6] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Friesland | Collaboration on tender and price agreements | Conduct did not influence the market; patients retained freedom of choice. | Exchange of competition sensitive information the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €2.020 m and €314 k | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [7] | 2010 | Home care | Two home care provider organizations in Province of Overijssel | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Create a competitive position vis-à-vis nationwide competitors | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €4.348 m and €1.304 m | Yes, see [v] in Table 3 |

| [8] | 2010 | Hospital care | Ten hospitals in Province Noord-Holland | Exchanging medical registration and production data | Develop regional data collection | Exchange of competition-sensitive information | Binding commitment: (1) no competition-sensitive information to be exchanged (2) and other providers to have insight into information exchanged under the same conditions as partner hospitals | No |

| [9] | 2011 | Home care | Two home care providers in the Randstad region | An agreement not to work in each other’s catchment area | Improve negotiation power | Noncompetition clause with the aim of restricting competition | Fines: €3 m, €1.343 m | No, fines repealed by ACM after [ii] [iii] |

| [10] | 2011 | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Fine: €7.719 m, cease and desist to remove and withdraw entry recommendations. | Yes, see [iv] in Table 3 |

| [11] | 2011 | Physiotherapy | Representative organization | Publication of an advice not to sign contracts with health insurers | Dispute between physiotherapists and health insurers | Potential of collective boycott | No, the association promised to comply with the competition act. | No |

| [12] | 2012 (see [10]) | GP Care | Representative organization | Publication of a document on a nonpublic part of their website, including recommendations to members to control the entry of GPs | Location policy to balance supply and demand to guarantee high quality GP care | Impose entry barriers for new entrants with the aim of restricting competition | Binding commitment: The national GP Association and regional subdivisions promised, among other things: (1) not to interfere with contract negotiations (2) not to provide advice concerning contract signing or entry of new GPs. | |

| Case number . | Healthcare sectors . | Year . | Argumentation in court decision . | Court ruling . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [i] (following case 2) | Mental care | 2006/ 2008 | Insufficient justification of aim to restrict competition, insufficient research into legal and economic context | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible, and three out of four fines were first lowered and ultimately waived by ACM. One fine (€56 k) was not appealed. |

| [ii] (following case 3) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iii] (following case 4) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers, and insufficient justification whether the agreement could restrict competition | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iv] (following case 6) | Home care | 2015/ 2017 | Confirmation of violation cartel prohibition. | Fine lowered to €767 k through length of procedure and lower severity factor |

| [v] (following case 7) | Home care | 2013 | Insufficient justification of actual noncompetition clause | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fines |

| [vi] (following case 10) | GP care | 2015 | Recommendations on the website, concerning words, economic context and intention, are not an efficient means of restricting competition | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fine |

| Case number . | Healthcare sectors . | Year . | Argumentation in court decision . | Court ruling . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [i] (following case 2) | Mental care | 2006/ 2008 | Insufficient justification of aim to restrict competition, insufficient research into legal and economic context | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible, and three out of four fines were first lowered and ultimately waived by ACM. One fine (€56 k) was not appealed. |

| [ii] (following case 3) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iii] (following case 4) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers, and insufficient justification whether the agreement could restrict competition | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iv] (following case 6) | Home care | 2015/ 2017 | Confirmation of violation cartel prohibition. | Fine lowered to €767 k through length of procedure and lower severity factor |

| [v] (following case 7) | Home care | 2013 | Insufficient justification of actual noncompetition clause | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fines |

| [vi] (following case 10) | GP care | 2015 | Recommendations on the website, concerning words, economic context and intention, are not an efficient means of restricting competition | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fine |

| Case number . | Healthcare sectors . | Year . | Argumentation in court decision . | Court ruling . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [i] (following case 2) | Mental care | 2006/ 2008 | Insufficient justification of aim to restrict competition, insufficient research into legal and economic context | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible, and three out of four fines were first lowered and ultimately waived by ACM. One fine (€56 k) was not appealed. |

| [ii] (following case 3) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iii] (following case 4) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers, and insufficient justification whether the agreement could restrict competition | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iv] (following case 6) | Home care | 2015/ 2017 | Confirmation of violation cartel prohibition. | Fine lowered to €767 k through length of procedure and lower severity factor |

| [v] (following case 7) | Home care | 2013 | Insufficient justification of actual noncompetition clause | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fines |

| [vi] (following case 10) | GP care | 2015 | Recommendations on the website, concerning words, economic context and intention, are not an efficient means of restricting competition | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fine |

| Case number . | Healthcare sectors . | Year . | Argumentation in court decision . | Court ruling . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [i] (following case 2) | Mental care | 2006/ 2008 | Insufficient justification of aim to restrict competition, insufficient research into legal and economic context | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible, and three out of four fines were first lowered and ultimately waived by ACM. One fine (€56 k) was not appealed. |

| [ii] (following case 3) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iii] (following case 4) | Home care | 2012 | Insufficient justification of potential of competition between the providers, and insufficient justification whether the agreement could restrict competition | Order to conduct additional investigation and reconsider decision. Following this, ACM did not consider further investigation feasible. ACM declared the objection admissible and waived the fines. |

| [iv] (following case 6) | Home care | 2015/ 2017 | Confirmation of violation cartel prohibition. | Fine lowered to €767 k through length of procedure and lower severity factor |

| [v] (following case 7) | Home care | 2013 | Insufficient justification of actual noncompetition clause | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fines |

| [vi] (following case 10) | GP care | 2015 | Recommendations on the website, concerning words, economic context and intention, are not an efficient means of restricting competition | Annulment of ACM’s decision and fine |

III. RESULTS

A. Collaborations and Competition Enforcement

1. Formal Decisions (2004–2012)

Since it began to enforce general competition regulations in Dutch healthcare, the ACM has issued a total of twelve decisions involving (alleged) anticompetitive behaviour by healthcare provider organizations or representative bodies. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2 formal enforcement proceedings mainly took place in the first half of the study period (2004–2012). In the description below, the case numbers are shown in square brackets and correspond with those presented in Table 2. Eight cases gave rise to fines, sometimes combined with a cease-and-desist order. In four cases, the organization(s) involved agreed to a binding commitment to discontinue the anticompetitive conduct to remedy the situation. After 2012, no more formal decisions were issued. The majority of the (alleged) violations of cartel regulations took place in the homecare sectors in the years following the 2006 reform. The anticompetitive conduct mainly concerned market-sharing agreements [3, 4], agreements on noncompetition clauses [7, 9] and the exchange of competition-sensitive information [6]. Homecare providers were sanctioned with fines ranging from €314,000 to €4,348,000. Although most of these cases involved individual healthcare providers, in four of the cases the offending parties were representative organizations, which had published online advice to their constituency of healthcare providers that was found to have infringed competition law. In dental care and mental care, the advice concerned the publication of reference prices [1, 2]. In GP care, it concerned the publication of recommendations aimed at controlling the entry of new GPs into existing markets [10]. In the physiotherapy sector, the advice was aimed at delaying the signing of contracts with health insurers, which was viewed as a call for a collective boycott [11]. There was only one case in the hospital sector [8]: ten hospitals agreed on the exchange of production and registration data. After the involvement of the ACM, they made a binding commitment not to exchange competition-sensitive information that could be used for strategic purposes.

Only three fines remained (partly) in place [1, 2, 6]. As the court rulings and argumentations in Table 3 show, many organizations appealed against the decisions issued by the ACM. In summary, these court rulings say much about the functioning of competition policy in several ways. Firstly, appeals and objections by healthcare providers have often been successful. Both the courts and Commission for Appeals for Business and Industry (Cbb) ordered decisions to be reconsidered or annulled. The ACM waived fines or rescinded decisions following these objections. Secondly, the level of proof required by the courts was high. This was particularly true with regard to the justification of whether there was scope for competition in the specific sectors, and the justification of whether the alleged conduct restricted competition and thus constituted an infringement of competition law. In three cases [i, ii, iii, Table 4], the court ordered the ACM to conduct additional research regarding the legal and economic context. The ACM, however, set different priorities and was also suffering from staff shortages, and did not consider the investigation feasible due to the time that had elapsed between the start of the case and the court’s final decision.

| Case number . | Year . | Healthcare sectors . | Type of collaboration . | Type of document . | Efficiencies claimed by collaborating parties . | (Risk of) anticompetitive behaviour . | Decision/advice (ACM) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | 2005 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | More scope for price competitionEstablish balance between supply and demand | Temporary elimination of price competition through preference clause (6 months), reduced ability to differentiate | Limited restriction of competition through the temporary nature |

| [14] | 2006 | Hospitals, healthcare purchasing | Regional consultative body on product and capacity agreements | Informal opinion on request | Improved coordination of price and capacity after expiry of obligation to contract | Agreements may restrict competitionExchange of competition-sensitive information | Competition Act is not applicable as the consultative body is seen as mandatory for the execution of government policy, and power of decision lies with the government |

| [15] | 2013 | Pharmacies, hospitals | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | Improved monitoring of medicationMore efficient prescribingImproved measurement of performance | Cross-market agreement between noncompeting pharmacies | Competition Act is not applicable as the agreement only includes noncompeting pharmaciesCurrent market share of the cooperative association is lower than bagatelle threshold in Article 7 of Competition Act, thus Competition Act does not apply. |

| [16] | 2013 | Hospitals | Collaborations in general | General guidance | N/A | N/A | ACM attaches great importance to a well-executed ex-ante self-assessment which clearly substantiates whether the efficiencies outweigh the drawbacks of competition.Healthcare purchasers and patient associations should be involved |

| [17] | 2014 | Healthcare purchasing | Agreement on centralization of acute care | Informal opinion at ACM’s own initiative | Improved and more efficient acute care | Reduced freedom of choice for patients and insured parties resulting in a potential reduction in quality of care | Intended centralization potentially infringes Competition Act, due to reduced freedom of choiceReduced ability to differentiate and stand out of health insurersEfficiencies do not outweigh drawbacks for competition |

| [18] | 2014 | Healthcare providers, purchasers and municipalities in Long term care | Exchange of information between competing providers | General guidance | Legislative changes demand for exchange of information | Exchange of competition-sensitive information can restrict competition | For municipalities and procurement offices, the Competition Act does not apply and thus no restrictions imposed on the exchange of information.Between healthcare purchasers, exchange of information negotiated tariffs, cost prices, turnovers and strategic plans concerning operating areas is contrary to Competition Act. |

| [19] | 2015 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement with participating hospitals | Informal opinion on request | Lower prices for TNFi medication potentially resulting in lower insurance premiums | Reduced ability to differentiate for participating hospitalsAgreement might impose entry barriers | The purchasing agreement for all insured persons does not appreciably restrict competition on the hospital market |

| [20] | 2015 | Hospitals | Joint negotiation and standardization of breast cancer care | Informal opinion on request | Standardize breast cancer care provision to increase quality and efficiencyJoint negotiation with insurers increases efficiency | Potential expansion of the collaboration agreement by adding new hospitals must be disclosed | Because the six hospitals are located across the Netherlands, they are not considered direct competitors.The agreement does not appreciably restrict competition as the agreement only includes noncompeting hospitals |

| [21] | 2015 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | Risk of overcapacity or delay if all four proton therapy centres are contractedWithout joint purchasing, proton therapy in the Netherlands would not be viable | The joint purchasing agreement concerns almost all insured person in the Netherlands, and therefore reduces freedom of choiceAlso risk of increased travel time and restriction of supply | The purchasing agreement for all insured persons does appreciably restrict competition on the hospital market, and thus infringes the Competition Act.ACM does not informally approves the planJoint purchasing of foreign proton therapy centres is permissible under the Competition Act. |

| [22] | 2015 | GP care | Collaborations in general | Guidance | N/A | Restricting freedom of choice or innovationCollective boycotts or tariff agreements | ACM will only take action if collaboration harms patients or interests of insured persons. |

| [23] | 2016 | Healthcare purchasing/hospitals | Joint purchasing agreement for hospitals and healthcare purchasers | Informal opinion at ACM’ own initiative | Negotiating lower prices, higher discounts and better conditions with pharmaceutical companies | Potential reduction in quality and innovation efforts. | The agreement may be permissible under the Competition Act. To safeguard competition, three conditions apply:Joint purchasing only applies to a part of the total costs.Entry to the purchasing group must be possible.The purchasing group does not impose any obligations such as binding contracts, withdrawal barriers and purchase obligations |

| [24] | 2016 | Hospital | Centralization agreement on complex oncological surgery | Informal opinion on request | Better quality through higher annual volume of surgeryMeet minimum volume thresholds | Reduced freedom of choice for patients and health insurers. | ACM considers the agreement restricting competition to be permissible under the exemption criteria of Article 6(3).The centralization is the least restricting option. Sufficient competition on other domains remains possible. |

| [25] | 2017 | Home care | Regional consultative body on joint purchasing | Informal opinion on request | Stimulating innovation in home careNationwide coverage | The agreement would eliminate alternativesAbility to maintain prices above competitive levels | ACM considers the agreement restricting competition to be permissible under the exemption criteria of Article 6(3). |

| [26] | 2018 | Obstetric care | Regional collaborative agreement on healthcare provision | Guidance | Quality improvements through multidisciplinary consultations, regional investment, professional standards | Price agreements, distribution agreements on clients, entry barriers | Entry to the collaboration by other organizations must be possibleThe entry process must be transparent, objective and nondiscriminating |

| [27] | 2019 | Healthcare purchasing, healthcare provision | Healthcare provision and substation agreements | Guidance | Provide care at the most cost-efficient location, close to patient. | Entry barriers, exchange of competition sensitive information, price increases | ACM will not take action against or fine healthcare providers for these agreements provided all of the following five criteria are satisfied: (1) There is a widely supported and public vision for the region that outlines the allocation of care. (2) Agreements on allocation and intended goals are substantiated. (3) Healthcare providers, health insurers and patient associations are fully involved. (4) The agreements do not focus on restricting or hindering the entry or expansion of the agreement’ activities. (5) The agreements and intended goals and measurability are transparent and public. |

| [28] | 2019 | Hospitals | Expansion of collaboration described under [20] | Re-evaluation | Share best practices to improve quality of careReward quality improvements | Weakened market position of health insurers vis-à-vis the agreementSharing of financial information could push prices upwards | The agreement may restrict competitionHealth insurers should decide whether they will negotiate with independent hospitals or with the group of hospitals |

| [29] | 2020 | Healthcare purchasing | Covid-19: health insurer agreements on compensation of healthcare providers | Guidance | Avoid bankruptcy of healthcare providersMeet duty of continuity in care | N/A | Collaboration between purchasers is necessary to maintain supply of care servicesAn independent organization should assess the amount of compensationThe agreement should be temporary in nature |

| [30] | 2020 | Healthcare provision/manufacturing | Covid-19: agreement on distribution of essential medication | Guidance | Avoid medication shortages | Exchange of capacity information between manufacturers | No risks to competition due to temporary and mandatory nature of agreement |

| [31] | 2020 | Healthcare purchasing | Covid-19: agreement on allocation of additional costs | Guidance | Avoid increase in premiums of some health insurersMaintain level playing field between insurers | Reduced functioning of risk equalizationReduced incentive to purchase cost-efficient care | The functioning of the health system would be jeopardized without allocation of costs.Permissible due to temporary nature of agreement |

| [32] | 2020 | Hospitals | Allocation of care agreement following [26] | Guidance | Improve quality of careContain rising healthcare spending | Reduced freedom of choice for patients and health insurers. | Correct application of the JZOJP conditionsAllocation of care is closely monitored to avoid negative effects on affordability and accessibilityDocuments on underlying argumentation should be published publicly on the hospital’s website |

| Case number . | Year . | Healthcare sectors . | Type of collaboration . | Type of document . | Efficiencies claimed by collaborating parties . | (Risk of) anticompetitive behaviour . | Decision/advice (ACM) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | 2005 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | More scope for price competitionEstablish balance between supply and demand | Temporary elimination of price competition through preference clause (6 months), reduced ability to differentiate | Limited restriction of competition through the temporary nature |

| [14] | 2006 | Hospitals, healthcare purchasing | Regional consultative body on product and capacity agreements | Informal opinion on request | Improved coordination of price and capacity after expiry of obligation to contract | Agreements may restrict competitionExchange of competition-sensitive information | Competition Act is not applicable as the consultative body is seen as mandatory for the execution of government policy, and power of decision lies with the government |

| [15] | 2013 | Pharmacies, hospitals | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | Improved monitoring of medicationMore efficient prescribingImproved measurement of performance | Cross-market agreement between noncompeting pharmacies | Competition Act is not applicable as the agreement only includes noncompeting pharmaciesCurrent market share of the cooperative association is lower than bagatelle threshold in Article 7 of Competition Act, thus Competition Act does not apply. |

| [16] | 2013 | Hospitals | Collaborations in general | General guidance | N/A | N/A | ACM attaches great importance to a well-executed ex-ante self-assessment which clearly substantiates whether the efficiencies outweigh the drawbacks of competition.Healthcare purchasers and patient associations should be involved |

| [17] | 2014 | Healthcare purchasing | Agreement on centralization of acute care | Informal opinion at ACM’s own initiative | Improved and more efficient acute care | Reduced freedom of choice for patients and insured parties resulting in a potential reduction in quality of care | Intended centralization potentially infringes Competition Act, due to reduced freedom of choiceReduced ability to differentiate and stand out of health insurersEfficiencies do not outweigh drawbacks for competition |

| [18] | 2014 | Healthcare providers, purchasers and municipalities in Long term care | Exchange of information between competing providers | General guidance | Legislative changes demand for exchange of information | Exchange of competition-sensitive information can restrict competition | For municipalities and procurement offices, the Competition Act does not apply and thus no restrictions imposed on the exchange of information.Between healthcare purchasers, exchange of information negotiated tariffs, cost prices, turnovers and strategic plans concerning operating areas is contrary to Competition Act. |

| [19] | 2015 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement with participating hospitals | Informal opinion on request | Lower prices for TNFi medication potentially resulting in lower insurance premiums | Reduced ability to differentiate for participating hospitalsAgreement might impose entry barriers | The purchasing agreement for all insured persons does not appreciably restrict competition on the hospital market |

| [20] | 2015 | Hospitals | Joint negotiation and standardization of breast cancer care | Informal opinion on request | Standardize breast cancer care provision to increase quality and efficiencyJoint negotiation with insurers increases efficiency | Potential expansion of the collaboration agreement by adding new hospitals must be disclosed | Because the six hospitals are located across the Netherlands, they are not considered direct competitors.The agreement does not appreciably restrict competition as the agreement only includes noncompeting hospitals |

| [21] | 2015 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | Risk of overcapacity or delay if all four proton therapy centres are contractedWithout joint purchasing, proton therapy in the Netherlands would not be viable | The joint purchasing agreement concerns almost all insured person in the Netherlands, and therefore reduces freedom of choiceAlso risk of increased travel time and restriction of supply | The purchasing agreement for all insured persons does appreciably restrict competition on the hospital market, and thus infringes the Competition Act.ACM does not informally approves the planJoint purchasing of foreign proton therapy centres is permissible under the Competition Act. |

| [22] | 2015 | GP care | Collaborations in general | Guidance | N/A | Restricting freedom of choice or innovationCollective boycotts or tariff agreements | ACM will only take action if collaboration harms patients or interests of insured persons. |

| [23] | 2016 | Healthcare purchasing/hospitals | Joint purchasing agreement for hospitals and healthcare purchasers | Informal opinion at ACM’ own initiative | Negotiating lower prices, higher discounts and better conditions with pharmaceutical companies | Potential reduction in quality and innovation efforts. | The agreement may be permissible under the Competition Act. To safeguard competition, three conditions apply:Joint purchasing only applies to a part of the total costs.Entry to the purchasing group must be possible.The purchasing group does not impose any obligations such as binding contracts, withdrawal barriers and purchase obligations |

| [24] | 2016 | Hospital | Centralization agreement on complex oncological surgery | Informal opinion on request | Better quality through higher annual volume of surgeryMeet minimum volume thresholds | Reduced freedom of choice for patients and health insurers. | ACM considers the agreement restricting competition to be permissible under the exemption criteria of Article 6(3).The centralization is the least restricting option. Sufficient competition on other domains remains possible. |

| [25] | 2017 | Home care | Regional consultative body on joint purchasing | Informal opinion on request | Stimulating innovation in home careNationwide coverage | The agreement would eliminate alternativesAbility to maintain prices above competitive levels | ACM considers the agreement restricting competition to be permissible under the exemption criteria of Article 6(3). |

| [26] | 2018 | Obstetric care | Regional collaborative agreement on healthcare provision | Guidance | Quality improvements through multidisciplinary consultations, regional investment, professional standards | Price agreements, distribution agreements on clients, entry barriers | Entry to the collaboration by other organizations must be possibleThe entry process must be transparent, objective and nondiscriminating |

| [27] | 2019 | Healthcare purchasing, healthcare provision | Healthcare provision and substation agreements | Guidance | Provide care at the most cost-efficient location, close to patient. | Entry barriers, exchange of competition sensitive information, price increases | ACM will not take action against or fine healthcare providers for these agreements provided all of the following five criteria are satisfied: (1) There is a widely supported and public vision for the region that outlines the allocation of care. (2) Agreements on allocation and intended goals are substantiated. (3) Healthcare providers, health insurers and patient associations are fully involved. (4) The agreements do not focus on restricting or hindering the entry or expansion of the agreement’ activities. (5) The agreements and intended goals and measurability are transparent and public. |

| [28] | 2019 | Hospitals | Expansion of collaboration described under [20] | Re-evaluation | Share best practices to improve quality of careReward quality improvements | Weakened market position of health insurers vis-à-vis the agreementSharing of financial information could push prices upwards | The agreement may restrict competitionHealth insurers should decide whether they will negotiate with independent hospitals or with the group of hospitals |

| [29] | 2020 | Healthcare purchasing | Covid-19: health insurer agreements on compensation of healthcare providers | Guidance | Avoid bankruptcy of healthcare providersMeet duty of continuity in care | N/A | Collaboration between purchasers is necessary to maintain supply of care servicesAn independent organization should assess the amount of compensationThe agreement should be temporary in nature |

| [30] | 2020 | Healthcare provision/manufacturing | Covid-19: agreement on distribution of essential medication | Guidance | Avoid medication shortages | Exchange of capacity information between manufacturers | No risks to competition due to temporary and mandatory nature of agreement |

| [31] | 2020 | Healthcare purchasing | Covid-19: agreement on allocation of additional costs | Guidance | Avoid increase in premiums of some health insurersMaintain level playing field between insurers | Reduced functioning of risk equalizationReduced incentive to purchase cost-efficient care | The functioning of the health system would be jeopardized without allocation of costs.Permissible due to temporary nature of agreement |

| [32] | 2020 | Hospitals | Allocation of care agreement following [26] | Guidance | Improve quality of careContain rising healthcare spending | Reduced freedom of choice for patients and health insurers. | Correct application of the JZOJP conditionsAllocation of care is closely monitored to avoid negative effects on affordability and accessibilityDocuments on underlying argumentation should be published publicly on the hospital’s website |

| Case number . | Year . | Healthcare sectors . | Type of collaboration . | Type of document . | Efficiencies claimed by collaborating parties . | (Risk of) anticompetitive behaviour . | Decision/advice (ACM) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | 2005 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | More scope for price competitionEstablish balance between supply and demand | Temporary elimination of price competition through preference clause (6 months), reduced ability to differentiate | Limited restriction of competition through the temporary nature |

| [14] | 2006 | Hospitals, healthcare purchasing | Regional consultative body on product and capacity agreements | Informal opinion on request | Improved coordination of price and capacity after expiry of obligation to contract | Agreements may restrict competitionExchange of competition-sensitive information | Competition Act is not applicable as the consultative body is seen as mandatory for the execution of government policy, and power of decision lies with the government |

| [15] | 2013 | Pharmacies, hospitals | Joint purchasing agreement | Informal opinion on request | Improved monitoring of medicationMore efficient prescribingImproved measurement of performance | Cross-market agreement between noncompeting pharmacies | Competition Act is not applicable as the agreement only includes noncompeting pharmaciesCurrent market share of the cooperative association is lower than bagatelle threshold in Article 7 of Competition Act, thus Competition Act does not apply. |

| [16] | 2013 | Hospitals | Collaborations in general | General guidance | N/A | N/A | ACM attaches great importance to a well-executed ex-ante self-assessment which clearly substantiates whether the efficiencies outweigh the drawbacks of competition.Healthcare purchasers and patient associations should be involved |

| [17] | 2014 | Healthcare purchasing | Agreement on centralization of acute care | Informal opinion at ACM’s own initiative | Improved and more efficient acute care | Reduced freedom of choice for patients and insured parties resulting in a potential reduction in quality of care | Intended centralization potentially infringes Competition Act, due to reduced freedom of choiceReduced ability to differentiate and stand out of health insurersEfficiencies do not outweigh drawbacks for competition |

| [18] | 2014 | Healthcare providers, purchasers and municipalities in Long term care | Exchange of information between competing providers | General guidance | Legislative changes demand for exchange of information | Exchange of competition-sensitive information can restrict competition | For municipalities and procurement offices, the Competition Act does not apply and thus no restrictions imposed on the exchange of information.Between healthcare purchasers, exchange of information negotiated tariffs, cost prices, turnovers and strategic plans concerning operating areas is contrary to Competition Act. |

| [19] | 2015 | Healthcare purchasing | Joint purchasing agreement with participating hospitals | Informal opinion on request | Lower prices for TNFi medication potentially resulting in lower insurance premiums | Reduced ability to differentiate for participating hospitalsAgreement might impose entry barriers | The purchasing agreement for all insured persons does not appreciably restrict competition on the hospital market |

| [20] | 2015 | Hospitals | Joint negotiation and standardization of breast cancer care | Informal opinion on request | Standardize breast cancer care provision to increase quality and efficiencyJoint negotiation with insurers increases efficiency | Potential expansion of the collaboration agreement by adding new hospitals must be disclosed | Because the six hospitals are located across the Netherlands, they are not considered direct competitors.The agreement does not appreciably restrict competition as the agreement only includes noncompeting hospitals |