-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andriani Kalintiri, Analytical Shortcuts in EU Competition Enforcement: Proxies, Premises, and Presumptions, Journal of Competition Law & Economics, Volume 16, Issue 3, September 2020, Pages 392–433, https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhaa013

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Analytical shortcuts lie at the heart of competition enforcement and have crucial implications for both substance and procedure. Nevertheless, not all of them are created equal. This point has been rather missed in competition scholarship due to the tendency to use the term ‘presumption’ in an overly expansive and ultimately inaccurate manner. Aspiring to inject some conceptual clarity in the discussion, this work proposes a taxonomy for distinguishing common analytical shortcuts in law enforcement comprising proxies, premises, and presumptions in the technical sense. With this taxonomy in mind, it then takes a closer look at their operation in EU competition enforcement in particular. As the article demonstrates, proxies, premises, and presumptions play an intricate and multilayered role in the interpretation and application of the EU antitrust and merger rules that the generic use of the term ‘presumption’ fails to adequately capture. Given their significance for the effectiveness, efficiency, and accuracy of enforcement, competition authorities and courts should be conscious of their function and of their substantive and procedural implications and should use them appropriately and wisely.

I. INTRODUCTION

One of the core challenges the law is faced with is how to manage uncertainty, difficulty, and complexity. Indeed, policymakers and adjudicators are regularly confronted with the exacting task of making sound and efficient choices about the meaning of the legal rules and their application. Often, these choices not only have far-reaching implications for economy and society, but they are also made in the light of limited information and subject to time and resource constraints. Against this backdrop, it is vital for the legal system to identify ways to cope with these challenges. In this regard, shortcuts may be employed to provide partial relief. A shortcut may be loosely defined as ‘an accelerated way of doing or achieving something’.1 Given its breadth, a diverse array of procedures, tools, and mental processes may come within the scope of the notion—from summary judgments to fast-track proceedings to heuristics and so forth. Irrespective of their precise form, however, shortcuts generally share a common feature: they have the capacity to simplify and rationalize law enforcement. In this sense, they constitute an intrinsic feature of most, if not all, legal systems.

Competition regimes are not an exception. The use of negotiated procedures in many jurisdictions, such as the cartel settlement procedure in the European Union (EU), is an obvious example of a shortcut aimed at maximizing administrative efficiency.2 Beyond such mechanisms, however, the discipline is rife with shortcuts engaged—whether consciously or not—in the construction and application of the competition rules, which one might call ‘analytical’. For example, the wisdom that certain arrangements—such as cartels—are inherently bad for competition and lack an efficiency justification underpins their prohibition as prima facie unlawful without it being necessary to demonstrate actual or likely anticompetitive effects on an ad hoc basis. On the other hand, practices that satisfy certain conditions and fall within pre-identified ‘safe harbours’ are deemed to be lawful. Moreover, it is often said that dominance may be inferred where the market share of the undertaking in question exceeds 50% or that parent companies which wholly own a subsidiary may be considered to have actually exercised decisive influence over its conduct and so forth.

In competition scholarship, these analytical shortcuts are often indistinctly referred to as ‘presumptions’.3 This tendency is certainly understandable to some extent. Generally, to presume means ‘to accept something in the absence of the further relevant information that would ordinarily be deemed necessary to establish it’.4 Contrary to pure assumptions, such acceptance is not without foundation. Rather, presumptions are predicated on a preliminary issue and invariably take the form of a statement that ‘if A, then B’. However, the ‘if A, then B’ format is typical of logical reasoning in general and of legal reasoning in particular. Therefore, relying on it as a compass for the detection of presumptions may lead to the inaccurate classification of different tools and processes as such. The issue is not purely terminological though. While their precise function has been vigorously contested in evidence literature,5 there is consensus that presumptions have a specific procedural consequence: they automatically shift the burden of proof onto the party against whom they operate with respect to the presumed issue. The same, however, is not true of other analytical shortcuts, such as proxies and premises. Although the latter may also be described in a ‘if A, then B’ manner, as will be explained shortly, their operation in the enforcement system differs.

In this light, the aim of this article is to examine the role of analytical shortcuts—specifically of proxies, premises, and presumptions—in competition enforcement with a focus on the regime of the EU, as well as their substantive and procedural implications. This inquiry is significant, if anything, for two reasons. First, the indiscriminate use of the term ‘presumptions’ in competition scholarship has created considerable confusion about the actual role and implications of proxies, premises, and presumptions in antitrust and merger enforcement. Their systematic exploration will not only introduce much-needed conceptual clarity, but it will also allow for the debunking of some common misconceptions. Second, many of the debates, which resurface every now and then in the discipline—for instance, about the goals of competition law or the role of economics—trigger the same fundamental question, that is, how new thinking and knowledge may become embedded in the enforcement system. Recognizing the existence of different analytical shortcuts and understanding their function is crucial to answering this question, insofar as it may enable us, on the one hand, to better frame the various discussions and, on the other hand, to critically evaluate the merits of the different ‘options’ for accommodating new ideas and insights in the application of the antitrust and merger provisions.

The main contribution of this article consists in the development of a taxonomy of analytical shortcuts in competition enforcement, comprising proxies, premises, and presumptions. With this conceptual framework as its starting point, the analysis demonstrates that proxies, premises, and presumptions play an intricate and multilayered role in the interpretation and application of the EU antitrust and merger rules that the generic use of the term ‘presumption’ fails to adequately capture. In discussing the function of these shortcuts in EU competition enforcement, the article addresses, among others, two highly important issues. First, it considers the proper use of presumptions, advancing the view that, from a fairness perspective, presumptions should only shift the evidential burden—that is, the burden of producing evidence—on the party against whom they operate. Second, it contemplates whether economic premises should be elevated to ‘presumptions of anticompetitiveness’ as per recent calls to this effect in the light of the challenges of the digital economy, ultimately cautioning against such measures. Irrespective of whether one agrees with these specific normative claims or not though, the central message of this article remains unaffected: considering that analytical shortcuts, such as proxies, premises, and presumptions, can make a real difference in how the competition provisions are enforced, agencies and courts must use them appropriately and wisely.

The analysis is structured as follows. Section II proposes a taxonomy of analytical shortcuts in law enforcement comprising proxies, premises, and presumptions with a view to introducing conceptual clarity in scholarly discussions and to showing why the indistinct use of the term ‘presumption’ is incorrect. With this taxonomy in mind, the rest of the article considers the operation of proxies, premises, and presumptions in EU competition enforcement in particular. Section III begins with proxies and highlights their significance for assessing relevant issues by enabling decision-makers to draw inferences from the evidence and for developing filters and screens, while also drawing attention to their possible limitations. Section IV is dedicated to premises: identifying normative assertions and economic propositions as the main types of generalized statements underpinning EU competition enforcement, it explains their function in the construction of the competition rules, the design of policy, and the assessment of the evidence. With this in mind, it also draws attention to their evolution over time and contemplates the extent to which economic premises in particular may be subject to the evidence rules. Last but not least, Section V examines presumptions in EU competition enforcement; offering first a brief account thereof, it critically assesses their function. Then, it considers whether economic premises should be elevated to presumptions of anticompetitiveness, as per recent proposals in the digital economy, and it highlights how blurred the line between presumptions and substantive law may be, noting, among others, the ensuing implications for national procedural autonomy. Section VI concludes.

II. A TAXONOMY OF ANALYTICAL SHORTCUTS IN LAW ENFORCEMENT: PROXIES, PREMISES, AND PRESUMPTIONS

While analytical shortcuts abound in law enforcement, a comprehensive account thereof has yet to be articulated.6 In the absence of a clear conceptual framework, however, confusion about their operation and implications for substance and procedure is only natural to ensue. With a view to laying the groundwork for the subsequent discussion, this section proposes a taxonomy of analytical shortcuts commonly employed in law enforcement in general and in competition enforcement in particular comprising the following three categories: proxies, premises, and presumptions, in the technical sense. Although this taxonomy is not claimed to be exhaustive, it is still valuable, insofar as it provides the necessary language for classifying different analytical shortcuts and for exposing their operation in the enforcement system.

Starting with proxies, these may be broadly defined as a substitute for determining something that one may not assess directly, whether at all or easily so.7 In this sense, proxies are metrics that provide indirect and imperfect approximations of the issues one attempts to estimate.8 For example, in combination with other indicators, student evaluations are traditionally employed as a proxy for assessing teaching excellence in higher education. Unsurprisingly, proxies play an important role in law enforcement, too; the application of many legal concepts becomes possible only through the identification and use of suitable metrics and benchmarks that decision-makers can refer to when assessing relevant factors. In tax law, for instance, proxies such as rates and book-tax differences have been employed to determine corporate tax avoidance.9 Generally, proxies have two important functions in law enforcement: on the one hand, they enable adjudicators to draw inferences from the available evidence about the facts of a case, and, on the other hand, they provide the foundation for developing filters and screens with a view to demarcating lawful from unlawful behaviour. The selection of appropriate metrics typically rests on common sense and experience, and thus the proxies in use may evolve. Once identified though, they serve to forego some analysis—that is, of how best to measure the issue in question, hence their qualification as ‘analytical shortcuts’.

Continuing with premises, these can be defined as generalized assertions or propositions that form the basis for making a choice.10 Such generalizations may be either normative or positive in nature and encapsulate past experience, existing knowledge, and divergent socio-political values. Generally, premises may shape law enforcement in three ways. First, they inform the design and interpretation of the law in two respects: on the one hand, they epitomize what the legal rules aim or should aim to protect, and, on the other hand, they enable enforcers to devise legal tests, which are both accurate and efficient.11 Second, the dominant premises steer administrative action and help authorities develop policy priorities and nonpriorities. Third, generalized assertions and propositions weave the backdrop against which evidence is assessed in adjudication, thereby equipping fact-finders with a barometer of normality as well as practical rules of thumb for making sense of the available information.12 Premises qualify as ‘analytical shortcuts’, insofar as their ‘validity’ or ‘truth’ need not be verified whenever the law is interpreted or enforced—in fact, policymakers and adjudicators often employ premises subconsciously when making choices about the construction and application of the legal rules. Nevertheless, such generalizations are not immune to challenges and may well be replaced over time in line with developments in knowledge and shifts in the contextual environment within which the law is enforced.

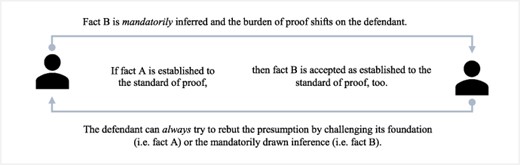

Finally, proxies and premises must be distinguished from a third type of analytical shortcut—that is, presumptions. The latter allow for an unknown fact to be deemed as established based on proof of another fact. In law enforcement, presumptions play an important role in the following sense. Decision-makers are often required to ascertain the ‘truth’ of the relevant facts in the absence of perfect information. In these circumstances, the risk of a mistaken ruling cannot be eliminated and is assigned between the parties through two linked rules: the legal burden (or burden of persuasion) and the standard of proof. The legal burden indicates who will be forced by law to take the risk of an error in case of a fact-finding failure, while the standard of proof indicates the level of probability or belief—depending on its conceptualization in the legal system at hand—that must be attained for the fact-finder to accept the evidence as proof. To successfully discharge their legal burden, the party carrying it must satisfy the standard of proof with respect to each constituent element of the substantive rule.13 Presumptions are a powerful mechanism in this regard, because they enable the person with the burden of persuasion regarding an issue to provisionally discharge it by proving another issue to the standard of proof (Figure 1).

Although scholarly attempts at a clear definition have not been entirely successful,14 presumptions differ from nonpresumptions in two respects: on the one hand, they require—rather than simply entitle—decision-makers to draw the entailed inference and to accept the presumed issue as ‘true’, and, on the other hand, ‘true’ presumptions are always rebuttable, that is, the party against whom they operate may in principle reverse them by producing evidence to the contrary.15

These characteristics can help us to tell presumptions apart from nonpresumptions and to take a critical look at the various ‘typologies’ occasionally put forward in the literature.16 For example, a distinction is commonly drawn between ‘presumptions of law’, understood as mandatorily drawn inferences, and ‘presumptions of fact’, understood as optional inferences that the decision-maker may draw at discretion. This language, however, is inapt. For one, the so-called presumptions of fact differ in no way from any other factual inference that a factfinder may—but is not required to—deduce based on the evidence.17 Furthermore, the term ‘presumptions of law’ can be confusing, if it is taken to mean that only the legislature can ever develop presumptions, to the exclusion of judges. Equally misguided is the categorization of presumptions into ‘substantive’ and ‘procedural’. ‘Substantive presumptions’ (sometimes called ‘presumptions of illegality’) are essentially a misnomer for substantive rules prohibiting certain types of behaviour, while ‘procedural presumptions’ are typically provisions aimed at regulating the enforcement procedure so as to ensure it will not come to a standstill—for example, provisions specifying the consequences of inaction after the expiration of a deadline.18 None of these are ‘true’ presumptions in that the ‘presumed’ issue is not a fact but rather a legal assessment or outcome. For similar reasons, the classification of presumptions into ‘provisional’ and ‘compelling’ or ‘conclusive’, depending on whether they can be reversed or not, is of doubtful value, too.19 The common rule, for instance, that, if a minor is of less than 8 years of age, they are incapable of criminal liability is sometimes described as a ‘compelling presumption’, but in reality it should be more accurately classified as a provision of substantive law.

These remarks reveal that the word ‘presumption’ has been used liberally to describe not only mandatory inferences about a fact but also optional inferences, as well as legal assessments and outcomes. To speak, however, of different ‘types’ of presumptions is inaccurate, if not potentially misleading—especially insofar as this language may create confusion about the way in which one may challenge a finding of legal liability and a presumption. Indeed, arguments against a provisional finding of liability are intended to establish that the person in question should not be held responsible and may take the form either of a justification showing that they did not act wrongfully or of an excuse showing that, although they did act wrongfully, they should nevertheless escape liability.20 By contrast, challenges to a presumption are directed against the ‘truth’ of the provisional or of the presumed fact. For example, the common presumption in many jurisdictions that a person is dead if they have been absent for 7 years or more may be overturned by showing either that the required number of years for the activation of this presumption has not been satisfied or that the person is still alive. While presumptions may be employed to establish that the conditions of the substantive rules are met on the facts of a specific case, the two are not the same and should not be conflated.

That said, a few additional clarifications are in order. First of all, while proxies, premises, and presumptions are conceptually and functionally distinct, they are used in parallel as well as in combination. For example, a proxy may be employed to formulate premises about, say, tax evasion. Likewise, to the extent that presumptions effectively entail a ‘decision’ to accept a fact B as ‘true’—absent evidence to the contrary—where a preliminary fact A has been established, they rest on premises. Nevertheless, not all premises are based on proxies nor do they always justify, or lead to, the emergence of a presumption. This latter remark is further important because only presumptions formally transfer the burden of proof with respect to the presumed issue onto the other party. By contrast, proxies simply entitle fact-finders to draw an inference about the issue in question, of which the metric is an approximation, while premises enable them to ‘connect the dots’ and make sense of the available evidence.

Decision-theoretic considerations may shed light on the choice to establish a presumption or not.21 Roughly speaking, the rationality of the decision to automatically shift or not the burden of proof with respect to a fact B upon proof of a preliminary fact A will depend on the probability of B being ‘true’ when A is ‘true’ and on the expected utility of the outcome under each act (i.e. automatic shift or not based on proof of A) and state (i.e. B as true versus B as not true) in terms of error minimization, given the implications for the accuracy, efficiency, and effectiveness of the fact-finding process. This remark may help explain why not every premise warrants the adoption of a presumption, as noted above. The latter may improve the efficiency and effectiveness of adjudication by expediting the proof process and by enabling fact-finders to overcome practical challenges without compromising on accuracy, only when it is grounded on generalizations that encapsulate common knowledge and/or strong consensus views.22 The corollary of this is that, while many premises may—and do—evolve over time, once adopted with good reason, presumptions are typically long-lasting and seldom revoked.

With these thoughts in mind, the following sections explore the operation of proxies, premises, and presumptions in EU competition enforcement.

III. PROXIES AS ANALYTICAL SHORTCUTS IN EU COMPETITION ENFORCEMENT

Proxies play a key role in EU competition enforcement. Indeed, the antitrust and merger provisions consist of indeterminate concepts—such as ‘dominance’ or ‘competition’ or ‘restriction’ or ‘abuse’—that are difficult, if not impossible, to establish directly. Because of this, the ability of competition authorities and courts to enforce the legal rules depends on the identification and use of suitable metrics and benchmarks for assessing the relevant issues and conducting the analysis.

Unsurprisingly, one may think of several examples of proxies in EU competition enforcement. Market shares, for instance, are commonly used as a detector of market power. In AKZO, the Court of Justice confirmed the earlier position in Hoffmann-La Roche that ‘very large shares are in themselves and save in exceptional circumstances, evidence of the existence of a dominant position’ and clarified that ‘that is the situation where there is a market share of 50%’.23 Similarly, the Commission has recognized that market shares provide a ‘useful first indication’ of the existence of market power.24 In the same vein, the authority has also acknowledged the usefulness of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) for gauging the levels of market concentration.25 Beyond market shares and concentration indexes, prices and cost measures are popular proxies for establishing harm to competition and consumers. In AKZO, for instance, the Court of Justice identified different cost benchmarks for determining when low pricing becomes predatory in violation of Article 102 TFEU.26 Last but not least, nonnumerical proxies are equally important. In tying cases, for example, the ‘separate products’ requirement arguably operates as a rough indicator of potentially harmful instances of tying.27 Likewise, in refusal to deal cases, the ‘indispensability’ requirement offers a proxy for detecting those situations where firms’ incentives to invest and innovate may be undermined.28

Naturally, proxies may be employed by competition authorities to formulate filters and screens. The various ‘safe harbours’, for instance, delineated by the Commission typically consist of market share and/or concentration thresholds, below which concerns are unlikely to arise.29 On the other hand, their use to develop presumptions should be treated with caution, since proxies offer approximations and are thus imperfect indicators of what is being estimated. Again, market shares are a good example in this regard. The statements in AKZO and Hoffmann-La Roche have been occasionally interpreted as establishing a ‘presumption of dominance’, where the market share of the undertaking exceeds 50%. While this claim is not unreasonable though, a closer look at the case law casts doubt on its merits. Indeed, the word ‘presumption’ has not been explicitly employed by the EU Courts. Furthermore, later judgments in particular feature the more nuanced term ‘indication’, which falls short of a presumption.30 Moreover, in all the cases where the finding of dominance has been challenged, including AKZO or cases of ‘superdominance’, it is clear that the Commission and the EU Courts took additional factors into account to verify the existence of a dominant position.31 Indeed, simply showing the existence of a market share of over 50% did not and does not enable the authority to automatically discharge its burden of proving dominance—and with good reason. While market shares may well offer a ‘useful first indication’, they are an imperfect indicator of an undertaking’s economic strength.32 As a result, any inferences drawn from them must be calibrated against other parameters before a finding of dominance is reached and the Commission’s burden of proof in this regard is deemed discharged.33 Consequently, while the temptation to develop presumptions on the basis of proxies may be strong, one should not succumb to it too readily.

That said, ‘one proxy does not fit all’ in competition enforcement. The choice of appropriate metric may depend on several factors—such as the degree of its accuracy, the features of the market, and the conduct in question—and thus it is important that the selected proxy be fit for purpose. Market shares, for example, might be a reliable indicator of economic power in conventional product markets but not in industries driven by innovation. This point was rightly emphasized in Cisco; agreeing with the Commission that ‘the consumer communications sector is a recent and fast-growing sector which is characterised by short innovation cycles in which large market shares may turn out to be ephemeral’, the Court acknowledged that ‘in such a dynamic context, high market shares are not necessarily indicative of market power (…)’.34 Similarly, a certain concentration index might be more or less precise in oligopolistic markets than in nonoligopolistic ones.35 In this regard, developments in economics may be valuable, to the extent that the proxies used in the application of the competition rules are inspired from this field. Recently, for instance, attention has been brought to profit margins as indicator of pricing power, sparking a debate on the extent to which they should be taken into account in merger policy and analysis.36

In this light, competition authorities and courts should be mindful of the proxies that they use and should regularly check whether there are better or new metrics and benchmarks to replace or complement the ones currently in use. Such conscious awareness and proactive attitude are crucial for a further reason: because proxies are sometimes the only way for estimating relevant considerations, the use of inappropriate metrics or the absence of suitable indicators may lead enforcers to conclusions that are inaccurate and short-sighted. Indeed, it is not sufficient to identify relevant factors, based on the law; decision-makers must be able to assess them in practice—otherwise, there is a potentially high chance these may be unduly disregarded or discounted. This challenge has been highlighted in recent years—especially with respect to market power in digital economy contexts and nonprice competition, in particular, innovation. As noted earlier, in fast-growing and dynamic markets, shares of supply may not be a reliable indicator of the competitive constraints faced by the parties. With this in mind, in recent merger cases, the Competition and Markets Authority in the United Kingdom has made an effort to identify and use more forward-looking measures—such as new user acquisitions based on app downloads or subscription numbers.37 Furthermore, while it is acknowledged that innovation is a crucial dimension of competition, it is not entirely clear how one may meaningfully measure innovation effects38—let alone balance them against ‘traditional’ price effects.39 In this respect, the Dow/DuPont merger decision constitutes a positive development. Regardless of whether one agrees with the outcome, the effort of the Commission to analyse innovation competition by reference to a variety of proxies, such as the parties’ expertise and assets, their R&D expenditure, and the strength of their patent portfolios, should be commended.40

IV. PREMISES AS ANALYTICAL SHORTCUTS IN EU COMPETITION ENFORCEMENT

A. The Function of Premises in EU Competition Enforcement

When applying the antitrust and merger rules, competition enforcers have to make a multitude of choices—from the goals that the discipline should aspire to attain to the type of cases that will provide the best use of the existing resources, the meaning to be given to the competition provisions, their accurate application to specific practices in view of the available information, and so forth. The motivation behind these choices is often communicated in a simplified form through premises—that is, generalized assertions or propositions that epitomize enforcers’ thinking. Naturally, premises of all sorts permeate competition enforcement, so much so that they are nearly impossible to document in an exhaustive manner. Nevertheless, two broad types of statements stand out and are worth highlighting: first, assertions about the goals of the discipline and, second, propositions about the impact of various practices on competition, the function of markets, and the behaviour of different stakeholders.

Indeed, the aims that competition law should pursue have been extensively debated on both sides of the Atlantic.41 On the one hand, the notions of efficiency and of consumer welfare, which are commonly identified as its optimal goals, lack a universal meaning.42 On the other hand, the political and societal context within which the competition rules are implemented may vary from place to place and from time to time.43 These variances have led to the emergence of divergent views about the role of competition law in the market and in society, which are typically summarized in the form of differing normative statements about the goals that the discipline should be concerned with. That said, a second type of propositions is equally common in competition enforcement—that is, economic premises. These are statements encapsulating knowledge derived from economics about the procompetitive and anticompetitive effects of a conduct, the circumstances in which competition may be harmed or the way in which rivals and consumers behave. Such premises sometimes sum up consensus positions in economics—one may think, for instance, of the economic insight that cartel conduct harms competition. Other times, however, they reflect divergent or even opposing views among economists—as, for example, the debate over what fosters innovation, that is, competitive markets or monopolies, illustrates.44

Normative and economic premises provide policymakers and adjudicators with valuable analytical shortcuts, insofar as they relieve them of the need to establish the merits of the entailed generalizations every single time they interpret and apply the competition rules. This is important in view of the far-reaching implications that the employed premises may have for competition enforcement.

Firstly, normative assertions and economic propositions are what gives shape to the otherwise vague letter of the antitrust and merger provisions. Arguably, those provisions do not immediately reveal what is prohibited and are in need of elaboration to become operational. In this process, varying perceptions about the goals of the discipline may completely shift the focus of the analysis.45 For example, if competition law is to be enforced with a view to protecting small- and medium-sized enterprises or employment—as opposed or in addition to, say, promoting consumer welfare—then different effects in the market may become relevant.46 On the other hand, economic premises about the procompetitive or anticompetitive nature of the conduct at hand typically inform the choice between the application of a ‘rule’ or a ‘standard’.47 The prohibition, for instance, of cartels as ‘by object’ violations of antitrust law rests on the economic premise that conduct of this kind lacks any efficiency justification and thus a rule of prima facie illegality is not liable to chill procompetitive behaviour.48 Conversely, the treatment of quantity rebates as prima facie lawful is grounded in the idea that this type of discount reflects the cost savings achieved by the undertaking in question.49 In the same vein, the ‘by effect’ analysis of exclusive dealing under Article 101(1) TFEU is explained by the economic insight that behaviour of this kind may entail efficiencies.50 Accordingly, normative and economic premises are instrumental in the construction of competition law.

It is worth noting at this point that in the EU the ‘by object’ test has been occasionally portrayed as a presumption of actual or likely anticompetitive effects. Arguably, the language employed by the EU Courts is partly to blame for this.51 In Cartes Bancaires, for instance, the Court of Justice explained that ‘certain collusive behaviour, such as that leading to horizontal price-fixing by cartels, may be considered so likely to have negative effects (…), that it may be considered redundant (…) to prove that they have actual effects on the market’, since ‘experience shows that such behaviour leads to falls in production and price increases, resulting in poor allocation of resources to the detriment, in particular, of consumers’.52 This wording though is confusing, insofar as it may create the misimpression that a finding of ‘by object’ violation rests on a presumption—in the technical sense of the word—of the existence of actual or likely anticompetitive effects in the circumstances at hand. Considering that presumptions shift the burden of proof, in this case it should be open to undertakings to challenge such a finding by showing that their cartel agreement, for instance, was never implemented or that the presumed negative effects are unlikely to occur. Nevertheless, the EU Courts’ jurisprudence demonstrates that such arguments may not reverse a finding of ‘by object’ liability.53 Consequently, to speak of a presumption of actual or likely anticompetitive effects is incorrect.

Secondly, premises also play a fundamental role in the design of administrative priorities—that is, the identification of cases on which the authority will choose to expend its limited resources to maximize the return on taxpayers’ money. For instance, if the goal is to promote consumer welfare, then it of course makes sense to prioritize investigations into practices which may have a bigger impact on it. Economic premises are critical in this screening exercise, since they can guide administrative agencies in detecting the most but also least ‘problematic’ types of behaviour in view of the pursued objective. For example, the prioritization of cartel enforcement worldwide rests on the economic insight that cartel conduct is among the most harmful for competition and consumers. Conversely, the development of ‘safe harbours’ setting out the circumstances where an authority is unlikely to intervene is grounded in the idea that competition is not liable to be impaired in the absence of a degree of market power. The Commission Guidelines on agreements of minor importance, for instance, explain that arrangements entered into between parties whose market shares do not exceed certain thresholds will be considered not to appreciably restrict competition in the meaning of Article 101(1) TFEU.54 Similar pronouncements may be located in the Commission Guidelines on horizontal cooperation agreements or in the Commission Guidelines on horizontal and nonhorizontal mergers.55 While these ‘safe harbours’ are often presented as ‘presumptions of lawfulness’, strictly speaking they are simply illustrations of the authority’s policy and understanding of the law.56

Last but not least, premises have a third important function in competition enforcement—they form part of the backdrop against which the standard of proof inquiry is conducted. The reason for this is that the process of determining whether the available evidence is sufficient to surpass the requisite level of conviction or probability for a decision to be lawfully adopted is informed—among others—by normality considerations, which allow us to make sense of the evidence and to ‘connect the dots’. Generally, our perception of ‘usual’ and ‘unusual’ is shaped by past experience and common sense.57 In competition enforcement though, economic premises may also determine what is ‘normal’ and what is not.58 For instance, because cartels are deemed to harm competition, claims and evidence of plausible explanations and efficiencies will be evaluated against this default idea. Likewise, the insight that ‘the effects of a conglomerate-type merger are generally considered to be neutral, or even beneficial, for competition’ led the General Court to emphasize in Tetra Laval that ‘the proof of anticompetitive conglomerate effects of such a merger calls for a precise examination, supported by convincing evidence, of the circumstances which allegedly produce those effects’.59 Therefore, premises inform not only the construction of the law and the design of policy but also fact-finding, insofar as they provide ‘rules of thumb’ and baselines for drawing inferences from the evidence.60

B. The Construction and Deconstruction of Normative and Economic Premises

Premises are not set in stone though. Because they embody contemporary norms and values as well as current knowledge, they may—and do—evolve over time. Societal and political shifts and advances in economics may lead to the emergence of new premises or the critical revisiting of old ones. The construction and deconstruction of normative and economic premises in competition enforcement occur in an incremental and cumulative manner predominantly outside but also within the legal system.

Outside the legal system, scholarly works exposing the thinking underlying competition enforcement and challenging its theoretical and empirical foundations, as well as its consistency, play a pivotal role in this regard. This is hardly surprising—by promoting evidence-based dialogue and allowing for the fermentation of ideas, academic debates may result in the elimination of weak propositions, the emergence of consensus positions, and the creation of new knowledge. This process though is a constant work in progress, which partly explains why many of the disputes concerning competition enforcement resurface now and again. The recently reignited conversation about the goals of the discipline is a good example of this—after the espousal by many of efficiency and consumer welfare as the main aims of competition law, the issue has again been brought into the spotlight by commentators advocating for the pursuit of broader social and political objectives.61 Economic premises are not immune to challenges either. As the currently ongoing discussion around the low levels of vertical merger enforcement illustrates, even well-established propositions—such as the idea that nonhorizontal concentrations generally benefit competition and generate efficiencies—may be questioned and potentially overturned.62 Finally, academic works exposing inconsistencies in the legal treatment of various categories of conduct may also cast doubt on the convincingness of the premises underlying the applicable tests.63

Within the legal system, the construction and deconstruction of premises naturally occur during the development of policy and in the context of specific cases. Indeed, on several occasions the emergence of new knowledge or changes in the prevailing circumstances have prompted competition authorities to reflect on—and update, where necessary—the premises driving their enforcement activities. In the EU, for instance, the heavy criticisms against the Commission’s early formalistic approach to the legal treatment of various practices led the authority to rethink its policy in different areas—from vertical agreements to horizontal arrangements to mergers and unilateral conduct. The replacement of old premises with new ones culminated in the publication of several soft law documents, which were seen as signalling a ‘more economic’ approach to EU competition enforcement.64 More recently, the challenges of the digital economy have impelled several authorities to commission expert reports and to launch task forces or strategies with a view to ascertaining what normative and economic premises should drive antitrust and merger policy in that context.65

By contrast, courts are naturally more cautious against regular or radical changes in the law as a result of contemporary developments due to the need to preserve legal certainty and stability.66 Nevertheless, the normative and economic propositions underpinning competition enforcement may be exposed or challenged in the context of judicial proceedings, too. Leegin is probably among the best examples of a drastic overhaul of the law in judicial acknowledgment of an evolution in current thinking. Noting that ‘economics literature is replete with procompetitive justifications for a manufacturer’s use of resale price maintenance’, the US Supreme Court overturned Dr Miles and dismissed the per se illegality test in favour of a rule of reason analysis.67 In the EU, the Courts have frequently spelt out the premises behind their interpretation of the law. While many have survived the passage of time relatively unscathed, for example, the idea that pricing below average variable costs is generally irrational for an undertaking or the insight that certain restraints are necessary in selective distribution or franchising,68 others have been tested—for instance, the idea that exclusivity rebates offered by a dominant firm are inherently harmful for competition and consumers.69 Over the years, such challenges have provided EU judges with the opportunity to incrementally clarify and elaborate on the main ideas driving the enforcement of the antitrust and merger rules.70

C. Economic Premises and Evidence Rules

Most, if not all, premises, in particular economic ones, have at least some empirical grounding, and their ‘truth’ or ‘validity’ may thus be contested, as just noted. To the extent that they underpin the construction of the competition provisions and their application to specific practices and may be challenged in the context of judicial proceedings, it is necessary to briefly consider whether they are subject to the evidence rules. Are economic propositions to be established to the standard of proof before being endorsed by the court? If there is disagreement between the parties about the ‘correct’ premise, say, for instance, regarding the competitive effects of exclusive dealing by dominant firms or the relationship between market structure and innovation, is this to be resolved in accordance with the rules on the burden of proof? And are judges exclusively dependent on parties to produce the relevant information, or can they engage in independent research?

These queries go to the heart of a rather old, yet highly important problem—that of the integration of social science in law.71 To the extent that the construction and the application of the legal rules hinge on ‘knowledge’ derived from social science, including economics, is this to be treated as ‘fact’ or as ‘law’ or perhaps as something else? Scholars have approached this question in different, albeit not fundamentally conflicting, ways. On the one hand, it has been suggested that so-called legislative facts—that is, facts that ‘inform (…) a court’s legislative judgment on questions of law and policy’—must be distinguished from adjudicative facts, that is, facts about ‘what the parties did, what the circumstances were, what the background conditions were’, and that the evidence rules apply only to the latter.72 On the other hand, it has been argued that social science may be treated both as ‘law’ and as a ‘fact depending on its use: it is akin to ‘law’ when it provides the basis for law-making or is employed to establish background knowledge and general methodology, while it is akin to ‘fact’, when it is applied to case-specific issues or to produce case-specific research findings.73

| Basis . | If A… . | …B . |

|---|---|---|

| Akzo | If the parent company wholly owns a subsidiary… | …it exercises decisive influence over its commercial conduct. |

| Anic | If undertakings have communicated with each other and have subsequently remained active in the market… | …their market conduct has been informed by the content of their communications. |

| Aalborg Portland | If an undertaking has attended a meeting (whose object is anticompetitive) … | …its will concurs with that of the other attendants (and it has thus participated in the agreement) |

| Dunlop | If there is evidence of anticompetitive instances sufficiently proximate in time… | …the infringement has continued uninterrupted in the period between. |

| T-Mobile, Murphy, Intel | If the conduct at hand lacks any plausible explanation… | …it is intrinsically capable of harming competition. |

| Basis . | If A… . | …B . |

|---|---|---|

| Akzo | If the parent company wholly owns a subsidiary… | …it exercises decisive influence over its commercial conduct. |

| Anic | If undertakings have communicated with each other and have subsequently remained active in the market… | …their market conduct has been informed by the content of their communications. |

| Aalborg Portland | If an undertaking has attended a meeting (whose object is anticompetitive) … | …its will concurs with that of the other attendants (and it has thus participated in the agreement) |

| Dunlop | If there is evidence of anticompetitive instances sufficiently proximate in time… | …the infringement has continued uninterrupted in the period between. |

| T-Mobile, Murphy, Intel | If the conduct at hand lacks any plausible explanation… | …it is intrinsically capable of harming competition. |

| Basis . | If A… . | …B . |

|---|---|---|

| Akzo | If the parent company wholly owns a subsidiary… | …it exercises decisive influence over its commercial conduct. |

| Anic | If undertakings have communicated with each other and have subsequently remained active in the market… | …their market conduct has been informed by the content of their communications. |

| Aalborg Portland | If an undertaking has attended a meeting (whose object is anticompetitive) … | …its will concurs with that of the other attendants (and it has thus participated in the agreement) |

| Dunlop | If there is evidence of anticompetitive instances sufficiently proximate in time… | …the infringement has continued uninterrupted in the period between. |

| T-Mobile, Murphy, Intel | If the conduct at hand lacks any plausible explanation… | …it is intrinsically capable of harming competition. |

| Basis . | If A… . | …B . |

|---|---|---|

| Akzo | If the parent company wholly owns a subsidiary… | …it exercises decisive influence over its commercial conduct. |

| Anic | If undertakings have communicated with each other and have subsequently remained active in the market… | …their market conduct has been informed by the content of their communications. |

| Aalborg Portland | If an undertaking has attended a meeting (whose object is anticompetitive) … | …its will concurs with that of the other attendants (and it has thus participated in the agreement) |

| Dunlop | If there is evidence of anticompetitive instances sufficiently proximate in time… | …the infringement has continued uninterrupted in the period between. |

| T-Mobile, Murphy, Intel | If the conduct at hand lacks any plausible explanation… | …it is intrinsically capable of harming competition. |

With these remarks in mind, when economic premises are employed for the purpose of determining the optimal legal test—that is, whether a conduct should be subject to a rule or a standard (in EU terminology, the ‘by object’ or the ‘by effect’ test)—they arguably escape the application of the evidence rules. In the EU this conclusion is further reinforced by the exclusive competence of the EU Courts to provide authoritative guidance on the meaning of EU law.74 Accordingly, conduct-specific economic premises, that is, generalized propositions pertaining to the economics of different practices—say, tying or price discrimination or refusal to supply—need not be established to the standard of proof to be accepted by EU judges as the motivation behind their choice of legal test. By contrast, where economic premises are employed as ‘background knowledge’ or even ‘rules of thumb’ for the purpose of making sense of the evidence, the answer is not as straightforward. As noted earlier, in this context economic premises may enable judges to draw inferences from the available pieces of information. Inevitably though, the strength of the inference is partly correlated with the strength or relevance of the economic premise. If either is prima facie challenged, then in principle the party with the burden of persuasion should explain why the inference should still be drawn.

V. PRESUMPTIONS AS ANALYTICAL SHORTCUTS IN EU COMPETITION ENFORCEMENT

A. A Brief Account of the Existing Presumptions

Somewhat ironically, considering the popularity of the term in competition scholarship, there are not many presumptions in the technical sense in EU competition law. Indeed, the examination of the EU Courts’ jurisprudence reveals the existence of only five (Table 1).75 These effectively correspond to different elements of the antitrust rules that the Commission must prove to adopt a prohibition decision.

The first presumption pertains to the notion of ‘undertaking’ against which Articles 101 and 102 TFEU are addressed.76 As explained in Höfner and Elser, the concept comprises ‘any entity engaged in an economic activity, regardless of the legal status of that entity and the way in which it is financed’.77 Further elaborating on this in Hydrotherm, the Court stressed that the term ‘undertaking’ must be understood as designating an economic—rather than a legal—unit.78 In this regard, the existence of distinct legal entities is immaterial; what matters is—as elucidated in Shell—that there is a ‘unitary organisation of personal, tangible and intangible elements which pursues a specific economic aim on a long-term basis and can contribute to the commission of an infringement’.79 In the case of parent companies and subsidiaries in particular, such an economic unit will exist where ‘the subsidiary does not decide independently upon its own conduct on the market, but carries out, in all material respects, the instructions given to it by the parent company’; according to settled jurisprudence, in these circumstances the anticompetitive conduct of the subsidiary may be imputed to the parent company.80 In Akzo the Court of Justice confirmed that ‘where a parent company has a 100% shareholding in a subsidiary (…) there is a rebuttable presumption that the parent company does in fact exercise decisive influence over the conduct of its subsidiary’.81 Ever since its first affirmation, the Akzo presumption has been reiterated multiple times and is now solidly rooted in the Courts’ jurisprudence.

In any event, to find a violation of Article 101(1) TFEU in particular, the Commission must also demonstrate that the undertaking participated in a collusive arrangement—be it a concerted practice or an agreement.82 Showing the existence of a concerted practice in principle entails proving three elements: concertation, subsequent market conduct, and causal connection between the two. In Hüls and in Commission v Anic Partecipazioni, however, the Court clarified that ‘subject to proof to the contrary, which it is for the economic operators concerned to adduce, there must be a presumption that the undertakings participating in concerting arrangements and remaining active on the market take account of the information exchanged with their competitors when determining their conduct on that market’.83 Ever since, the Anic presumption—as is often called—has become firmly embedded in the Courts’ case law.84 While it was initially developed in connection with concerted practices—that is, collusive arrangements falling short of an agreement—this presumption soon provided the basis for the emergence of another one, that of participation in a cartel upon evidence that the undertaking has attended a meeting with an anticompetitive object. Indeed, as confirmed for the first time in Aalborg Portland, ‘it is sufficient for the Commission to show that the undertaking concerned participated in meetings at which anticompetitive agreements were concluded, without manifestly opposing them, to prove to the requisite standard that the undertaking participated in a cartel’, the presumption being that its will concurs with that of the other attendants.85

At any rate, to adopt a prohibition decision, the Commission must also establish the duration of the antitrust violation and of the undertaking’s involvement in it. This can be a daunting task—especially in complex infringements extending over longer periods of time. In recognition of this challenge, the EU Courts have eased the authority’s burden of proof in two ways. Firstly, they have developed the doctrine of single, continuous or repeated infringement, according to which there is one infringement—rather than several—where a series of acts form part of an unlawful ‘overall plan’.86 The latter may be deduced ‘from the identical nature of the objectives of the practices at issue, of the goods concerned, of the undertakings which participated in the collusion, of the main rules for its implementation, of the natural persons involved on behalf of the undertakings, and lastly, of the geographical scope of those practices’.87 Secondly—and most importantly, for the purposes of this work, the EU Courts have adopted a presumption of continuity, whose foundations originate in Dunlop. According to the latter, ‘if there is no evidence directly establishing the duration of an infringement, the Commission should adduce at least evidence of facts sufficiently proximate in time for it to be reasonable to accept that that infringement continued uninterruptedly between two specific dates’.88

Finally, the case law arguably points at the existence of one more presumption—that is, if a conduct lacks any plausible explanation, it is intrinsically capable of harming competition.89 Premises about the economics of the practice at hand and any ‘objective justifications’ raised by the parties will be crucial to ascertaining whether, on the facts, there is no legitimate ground for it.90 In this case, the anticompetitive potential of the practice is automatically inferred and needs not be proved ad hoc, unless the undertaking concerned produces evidence to the contrary, and a ‘by object’ violation will be considered established, provided that the other elements of Article 101 TFEU or Article 102 TFEU have been sufficiently demonstrated. In the context of Article 101 TFEU, the Court of Justice explained in T-Mobile that ‘the distinction between “infringements by object” and “infringements by effect” arises from the fact that certain forms of collusion between undertakings can be regarded, by their very nature, as being injurious to the proper functioning of normal competition’.91 As the Court elaborated, ‘in order for a concerted practice to be regarded as having an anticompetitive object, it is sufficient that it has the potential to have a negative impact on competition’; in this case, there is no need for the Commission to consider its effects.92 Nevertheless, Football Association Premier League clarifies that undertakings may ‘put forward any circumstance within the economic and legal context’ of the arrangement in question, which would justify the finding that it is ‘not liable to impair competition’.93 A similar presumption is visible in the context of Article 102 TFEU, as well. Indeed, the judgment of the Court of Justice in Intel implies that practices, which lack a plausible explanation, are presumed to be capable of harming competition, unless the dominant undertaking challenges this conclusion ‘on the basis of supporting evidence’.94

B. The Function of the Existing Presumptions in EU Competition Enforcement

In EU competition law, the legal burden to demonstrate the existence of a violation of the antitrust rules rests with the Commission, in accordance with Article 2 of Regulation 1/2003 and the presumption of innocence that applies to competition proceedings and dictates that defendants cannot be required to prove their innocence.95 While undertakings generally bear an obligation to produce evidence in support of their claims, when disputing the authority’s arguments and adduced information, the burden of persuasion remains with the Commission, who must meet the standard of proof with respect to each constituent element of an antitrust violation to discharge it. As the case law of the EU Courts suggests, the applicable standard of proof in EU competition enforcement is ‘firm conviction’,96 and, to satisfy this, the Commission can rely on the five presumptions identified above. In this sense, the latter recalibrate the default allocation of the burden of proof in EU competition law by shifting part thereof onto undertakings. It is thus necessary to carefully examine the considerations underpinning the adoption of the five presumptions currently in existence and their precise operation.

Indeed, a closer look at the presumptions identified above reveals that all of them rest on solid positive premises. The Akzo presumption, for instance, reflects the reality that parent companies invariably determine the way in which their wholly owned subsidiaries conduct themselves in the market due to the existence of strong links of property and control between them. Moreover, as AK Kokott explained in her Opinion in T-Mobile, the presumed causal connection in Anic constitutes ‘nothing other than a legitimate conclusion drawn on the basis of common experience’; if the existence of a concertation among two or more undertakings has been established, it is only ‘natural to presume a relation of cause and effect’ between the concertation and the undertakings’ subsequent market behaviour.97 Likewise, the Aalborg Portland presumption rests on the idea that, where an undertaking participates in an anticompetitive meeting without objecting to it, it is only reasonable that the other participants will believe that it subscribes to what was decided and that it will comply with it. Furthermore, as far as the presumption of continuity is concerned, experience suggests that in offences that are committed over longer periods, there is typically a causal link between acts which are temporally proximate. Last but not least, the presumption of capability is grounded in past experience, common sense, and economic insights suggesting that conduct which lacks any plausible explanation has the intrinsic capacity to harm competition in the market concerned. In this light, it is unsurprising that occasional attacks against the accuracy of the existing presumptions have been unsuccessful.98

At the same time, the five presumptions currently in existence have played an important role in the efficiency and effectiveness of EU antitrust enforcement. Indeed, it is no coincidence that most were developed by the EU Courts in fact-intensive proceedings—invariably cartels. The main challenge of these cases lies in establishing the underlying facts: undertakings are typically aware of the unlawfulness of their conduct and thus strive to minimize or destroy any incriminating evidence. Since the burden of persuasion is borne by the Commission, its ability to enforce the antitrust rules in these circumstances would be compromised, were the authority expected to produce evidence of every aspect and detail of the infringement—firstly, because such evidence may not be available and, secondly, because even if it is available, its discovery may be too expensive to justify the benefit. In recognition of these practical difficulties, the Anic, the Aalborg Portland, the Dunlop, and the Akzo presumptions have shifted part of the evidentiary responsibility on defendant undertakings, thereby easing the Commission’s burden of proof. Remarkably, these presumptions are sometimes employed cumulatively—especially in cases involving complex infringements. For instance, the Anic presumption may be used in conjunction with the Aalborg Portland presumption and the presumption of continuity to establish an undertaking’s participation in an illegal arrangement, while the Akzo presumption may be engaged to facilitate the imputation to parent companies of liability for the antitrust transgressions of their subsidiaries.

These remarks confirm that the judicial choice to introduce the presumptions identified above was indeed sensible and in line with broader decision-theoretic considerations informing the adoption of presumptions, as briefly set out earlier. For one, their underpinning premises are so robust that the odds of the presumed fact not being ‘true’, once the basis of the presumption has been established to a ‘firm conviction’ threshold, are arguably very small, as is the risk of an inaccurate factual finding with the presumption—compared to without the presumption, which is further diminished in view of the ability to produce evidence to the contrary. At the same time, the benefits in terms of improved efficiency and effectiveness of EU antitrust enforcement are obvious: the existing presumptions allow for the more fruitful use of the Commission’s and the EU Courts’ limited time and resources, while, where evidence of the presumed issue is unavailable, they provide the only means for the authority to satisfy the standard of proof. Accordingly, the desirability of the five presumptions in existence in EU competition enforcement is difficult to challenge.

It is worth noting at this point that presumptions may promote concrete policy goals, too, and this is also true of the presumptions identified above, which are arguably grounded in widely endorsed normative premises, as well. For example, the Akzo presumption invigorates the idea that those with powers of supervision should be keeping an eye on the activities of their hierarchical subordinates to ensure that their behaviour remains compliant with the law.99 Likewise, the Anic presumption reinforces the well-established principle that ‘each economic operator must determine independently the policy which he intends to adopt on the common market’.100 Along similar lines, the Aalborg Portland presumption is intended to discourage passive modes of anticompetitive behaviour; as the Court of Justice has explained, ‘a party which tacitly approves of an unlawful initiative, without publicly distancing itself from its content or reporting it to the administrative authorities, effectively encourages the continuation of the infringement and compromises its discovery’.101 Furthermore, the presumption of continuity aims to promote the deterrent effect of enforcement by enabling the Commission to establish the duration of competition infringements in situations where there is no evidence of its existence for some periods of time. Finally, the presumption of capability conveys that undertakings should steer clear of practices that are inherently incompatible with competition on the merits, while it also communicates that Articles 101 and 102 TFEU should be concerned only with behaviour that may affect competition, other types of conduct falling outside their purview.

Nevertheless, the presumptions currently in existence in EU competition enforcement have not escaped criticism. Inasmuch as they shift the burden of proof onto undertakings, their operation has been denounced as incompatible with the principle of effective judicial protection and the right to a fair trial, as enshrined in Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (CFR) and Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), respectively. In this respect, it should be emphasized that presumptions are not automatically at odds with either as a matter of doctrine. Drawing on the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), the EU Courts have underlined that ‘a presumption, even where it is difficult to rebut, remains within acceptable limits so long as it is proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued, it is possible to adduce evidence to the contrary and the rights of the defence are safeguarded’.102 Accordingly, the fairness of the presumptions in operation in EU competition enforcement seems to be contingent on three elements: the strength of their underpinning premises; their rebuttability; and on the undertakings’ rights of defence being respected. The first and the third requirements are rather uncontroversial. As just explained, the five presumptions in existence rest on solid positive and normative premises, while the significance of the rights of defence in competition proceedings has been consistently reaffirmed by EU judges. By contrast, the requirement for ‘rebuttability’ calls for further examination: while there is no doubt that undertakings are allowed to produce evidence with a view to reversing a presumption, the level of evidence, which is necessary for a presumption to disappear is unclear.

In this regard, the critical question is what burden of proof presumptions shift—the burden of production or the burden of persuasion?103 This issue has been long yet inconclusively debated in evidence scholarship—so much so that some commentators have advocated forsaking the concept of presumptions altogether.104 According to one theory—principally defended by Thayer and Wigmore—presumptions merely shift the burden of producing evidence.105 If the party who bears the burden of persuasion with respect to fact ‘B’ demonstrates ‘A’, they are deemed to have satisfied the standard of proof in respect of ‘B’, unless their opponent produces evidence, which calls ‘B’ into question, in which case the presumption disappears. According to a second view, known as the ‘Morgan-McCormick’ theory, presumptions have the effect of transferring not only the burden of production but also the burden of persuasion.106 In this case, the party against whom the presumption operates has to disprove ‘B’ to the standard of proof to make it vanish, any doubt operating at their expense. The academic divide over the precise consequences of presumptions is not a purely theoretical matter; indeed, ‘persuasive’ presumptions function akin to defences, and thus their use may have a profound impact on the distribution of the legal burden between the parties.107

In EU competition enforcement, the jurisprudence of the EU Courts fails to provide a straightforward answer to this question. For example, the judicial clarification in Elf Aquitaine that evidence of the lack of actual exercise of decisive influence may be found within the sphere of operations of the parent company and the subsidiary possibly suggests that the Akzo presumption shifts only the burden of production.108 Nevertheless, the prevalent impression among undertakings and commentators is that parent companies are burdened with much more than merely an obligation to produce evidence capable of calling the existence of a single economic unit into question.109 On the other hand, the phrase ‘subject to proof to the contrary’ in Anic110 and the Courts’ perception of ‘public distancing’ as ‘a means of excluding liability’111 with respect to the Aalborg Portland presumption arguably connote a shift of the burden of persuasion, rather than the burden of production. Then again, the presumption of continuity seems to entail only a transfer of the evidential burden on defendant undertakings, given the importance attached by the EU Courts to the duration of the conduct at hand as one of the constituent elements of an antitrust violation.112 Last but not least, the procedural consequences of the presumption of capability are equally ambiguous.113 The wording of Intel indicates that it is sufficient for undertakings to challenge the presumption ‘on the basis of supporting evidence’, in which case the authority has to positively establish that the conduct is capable of harming competition.114 Commission officials, however, have seemingly interpreted the judgment to impose a much heavier, persuasive burden on firms.115

Against this backdrop, it is submitted that presumptions should only shift the burden of production. In other words, the undertaking against whom they operate should be able to reverse them by producing evidence capable of calling the ‘truth’ of the presumed fact into question. A key reason for this is that, albeit mandatorily drawn, presumptions remain at heart factual inferences, as any other factual inference that a decision-maker draws based on the evidence. Accordingly, it is not obvious why undertakings should be required to disprove them, rather than simply cast doubt on their ‘truth’.116 The mere fact that a presumption is difficult to reverse in practice does not automatically mean that it shifts the burden of persuasion. Considering the strength of their underpinning premises, it is only natural that instances of a successful reversal of the five presumptions in existence will be few and far between. Indeed, were a presumption easily reversed, this would suggest that its adoption in the first place might not have been sound. Assuming, however, that a presumption is well-justified—as is the case with all the five presumptions in existence in EU competition enforcement—and an undertaking has exceptionally succeeded in questioning the ‘truth’ of the presumed issue, this would be all the more reason for the party with the legal burden—here the Commission, to explain why the factual inference still holds true.

This approach is arguably mandated by the principle of effective judicial protection and the right to a fair trial, too. Generally, the allocation of the legal burden and the setting of the standard of proof embed specific fairness choices, which in EU competition enforcement reflect the application of the presumption of innocence. The decision whether to adopt a presumption or not embraces—rather than modifies—these default choices; as explained, presumptions simply provide the means for the party with the burden of persuasion with respect to the relevant fact at hand to satisfy the applicable standard of proof. Were presumptions to shift the burden of persuasion, this would modify the default allocation of the legal burden between the authority and undertakings, insofar as it would require undertakings to disprove—rather than call into question—the presumed fact, thereby turning them into defences. Since all five presumptions in existence are linked to different core elements composing an antitrust violation—for instance, the existence of an undertaking, the duration of the unlawful conduct, or the defendant’s participation in it—their operation would contravene the fundamental principle that it is for the Commission to establish the existence of an infringement and not for the defendants to prove their innocence, for example, by positively showing that they do not constitute an undertaking or that the duration of the agreement was not the presumed one or that they did not participate in the unlawful conduct. This problem would be further exacerbated in cases where the authority cumulatively relies on multiple presumptions.

Therefore, the EU Courts should clarify that, where a presumption is engaged, only the evidential burden is transferred on undertakings, as with factual inferences in general. Given the robustness of the premises underpinning the five presumptions in existence in EU competition enforcement, undertakings will be able to reverse them only in exceptional circumstances. As long as producing evidence capable of calling their ‘truth’ into question is sufficient though, this does not mean that they are ‘unfair’.

C. Should Economic Premises Be Elevated to ‘Presumptions of Anticompetitiveness’ in the EU?

Keeping in mind the above remarks about the function of presumptions, an important question begs consideration: should economic premises concerning specific types of behaviour and/or sets of market conditions be elevated to ‘presumptions of anticompetitiveness’, as is occasionally suggested?

Indeed, the argument has been advanced in the United States for the development of presumptions about the anti- or pro-competitive impact of various practices on competition based on their economics and the structure of the market with a view to clarifying what ‘an enquiry meet for the case’ requires.117 Furthermore, as noted earlier, the low levels of vertical merger enforcement have recently prompted scholars to question the empirical foundations of the economic premises guiding it and have led to proposals for the introduction of presumptions of harm, where certain conditions are satisfied.118 Last but not least, various reports published on antitrust and/or merger policy in the digital economy—most notably, the Expert Report on Competition Policy for the Digital Era in the EU (‘Digital Competition Policy Report’), the Expert Report on Unlocking Digital Competition in the United Kingdom (‘Furman Report’), and the Stigler Draft Report on Digital Platforms and Market Structure in the United States (‘Stigler Report’)—have contemplated and, on some occasions, recommended the adoption of ‘presumptions of anticompetitiveness’ as a means of remedying a perceived imbalance between under- and over-enforcement in the light of the risk of significant consumer harm in the absence of timely and sufficient intervention against problematic practices.119

By means of preliminary remark, it should be stressed, first of all, that US calls for the development of presumptions of pro- and anticompetitiveness build on the specifics of the US per se test of illegality and ‘rule of reason’ analysis. While these concepts bear similarities to the EU notions of ‘by object’ and ‘by effect’, they are not identical. Most notably, a finding of per se illegality is not open to challenge, contrary to ‘by object’ liability which undertakings are free to contest, while the ‘rule of reason’ analysis entails a balancing of the anticompetitive and procompetitive effects of the conduct in the context of a structured exercise based on burden-shifting, which is different from the ‘by effect’ test, which is focused on the actual or likely harm caused by the practice at hand. Since the conceptual and analytical differences between the US and the EU regimes have not been sufficiently exposed yet,120 one must be very cautious before drawing any parallels, given also the polar opposite ratios between private and public enforcement in each jurisdiction.

With this in mind, it is submitted that elevating economic premises about specific practices and market conditions to presumptions of anticompetitiveness may not be appropriate in the EU system. Recent proposals for the adoption of presumptions of harm—and for the transfer of the burden of proof on undertakings, more generally—are arguably aimed to strike a better balance between over- and under-enforcement in the digital era. In the face of uncertainty about the probability and cost of false convictions and false acquittals and in the light of the difficulties in assessing consumer harm, it was suggested in the Digital Competition Policy Report that ‘even where consumer harm cannot be precisely measured, strategies employed by dominant platforms aimed at reducing the competitive pressure they face should be forbidden in the absence of clearly documented consumer welfare gains’ and that ‘one may want to err on the side of disallowing potentially anticompetitive conducts, and impose on the incumbent the burden of proof for showing the pro-competitiveness of its conduct’.121

However legitimate though, the end does not automatically justify the means. If understood in the technical sense as mandatory factual inferences, it is difficult to see how such presumptions may be compatible with Article 2 of Regulation 1/2003 and with the presumption of innocence. Procedurally speaking, the practical difference of elevating economic premises to presumptions of anticompetitiveness is that the entailed inference of harm is to be obligatorily drawn, once the foundation of the presumption has been established.122 In this case, the burden of proof shifts on the defendant undertaking to oppose the factual finding that their conduct restricts competition. As explained though, for presumptions to be compatible with the principle of effective judicial protection and the right to a fair trial, they must be ‘proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued, it is possible to adduce evidence to the contrary and the rights of the defence are safeguarded’.123 Presumptions whose underpinning premises are not sufficiently strong to ensure that the entailed factual inference will be almost always accurate and which operate akin to defences by shifting the burden of persuasion—rather than merely the burden of production—on defendant undertakings fail to satisfy these requirements. Both remarks are crucial with respect to presumptions of anticompetitiveness. For one, it is not always obvious that the economic premises underpinning such proposed presumptions reflect common knowledge and consensus views. Moreover, while they are invariably presented as ‘rebuttable’, the intention behind calls for their adoption is often to relieve the Commission of its legal onus to demonstrate why a practice harms competition and to transfer to undertakings the burden of persuasion as to the procompetitiveness—and thus lawfulness—of their conduct.