-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Liang Yao, Gordon Guyatt, Zhikang Ye, John P. Bilezikian, Maria Luisa Brandi, Bart L. Clarke, Michael Mannstadt, Aliya A. Khan, Methodology for the Guidelines on Evaluation and Management of Hypoparathyroidism and Primary Hyperparathyroidism, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, Volume 37, Issue 11, 1 November 2022, Pages 2404–2410, https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4687

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

To develop guidelines for hypoparathyroidism and primary hyperparathyroidism, the panel assembled a panel of experts in parathyroid disorders, general endocrinologists, representatives of the Hypoparathyroidism Association, and systematic review and guideline methodologists. The guideline panel referred to a formal process following the Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) methodology to issue GRADEd recommendations. In this approach, panelists and methodologists formatted the questions, conducted systematic reviews, evaluated risk of bias, assessed certainty of evidence, and presented a summary of findings in a transparent fashion. For most recommendations, the task forces used a less structured approach largely based on narrative reviews to issue non‐GRADEd recommendations. The panel issued Eight GRADEd recommendations (seven for hypoparathyroidism and one for hyperparathyroidism). Each GRADEd recommendation is linked to the underlying body of evidence and judgments regarding the certainty of evidence and strength of recommendations, values and preferences, and costs, feasibility, acceptability and equity. This article summarizes the methodology for issuing GRADEd and non‐GRADEd recommendations for patients with hypoparathyroidism or hyperparathyroidism. © 2022 The Authors. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR).

This article describes the methodology used for the development of hypoparathyroidism and primary hyperparathyroidism guidelines. In this series of articles summarizing the efforts of an international group of experts in hypoparathyroidism and primary hyperparathyroidism, the authors conducted systematic reviews of a small number of selected questions and narrative reviews for other questions. Ultimately, the panel produced two types of recommendations, GRADEd (from Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Working Group [GRADE]) and non‐GRADEd, corresponding for the most part to issues for which systematic reviews were or were not undertaken. In this article, we describe the key elements of the methods the task forces used in developing their guidelines for hypoparathyroidism and primary hyperparathyroidism.

Composition, Selection, and Function of Guideline Task Forces

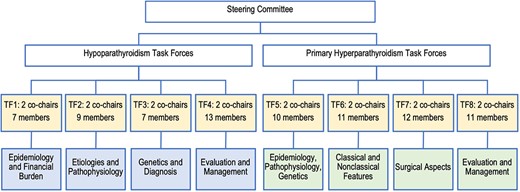

Six endocrinologists (JPB, MB, BLC, AAK, MM, JTP) made up the guideline steering committee. The honorary chair of the steering committee was John T. Potts. The cochairs of the steering committee were John P. Bilezikian and Aliya A. Khan. The steering committee met regularly and oversaw the entire guideline development process. The steering committee invited 11 endocrinologists to join them as cochairs, forming two task force groups, one for hypoparathyroidism (led by AAK) and the other for primary hyperparathyroidism (led by JPB). Each of these two task force groups consisted of four individual task forces (Fig. 1).

The task forces included specialists with expertise in parathyroid disease: endocrinologists, nephrologists, pathologists, epidemiologists, radiologists, pharmacologists, endocrine surgeons, and general endocrinologists. The steering committee selected task force members on the basis of their expertise and publications in the field with consideration given to international geographic representation. The steering committee gave equal preference to men and women. The Hypoparathyroidism Association was represented by two individuals. Fig. 1 describes the structure of the steering committee and the eight task forces.

The steering committee invited participation from methodologists from McMaster University with expertise in developing guidelines using the GRADE approach.(1,2) The full composition of the task forces included 93 experts in parathyroid disorders, four general endocrinologists, three methodologists, and two representatives of the Hypoparathyroidism Association. Seventeen countries and 45 institutions were represented. Industry employees were excluded.

All eight task forces held individual meetings on a regular basis to review the evidence, develop recommendations, and achieve consensus. Separate meetings were held regularly with the task force cochairs to guide and review the progress of the eight teams. The steering committee also met regularly to oversee the entire guideline development process.

Guideline Process

Each of the eight task forces focused on different aspects of the two diseases and developed a review paper. This series includes the four task force reviews on hypoparathyroidism and four task force reviews on primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition to the four reviews, the hypoparathyroidism task forces undertook four systematic reviews along with one survey evaluating monitoring practice for hypoparathyroidism. In addition to the four reviews, the primary hyperparathyroidism task forces undertook one systematic review. In total, five systematic reviews were completed and are published as part of this series. The cumulative repository of information from the aforementioned reviews were consolidated into two summary statement guideline papers: one for hypoparathyroidism and one for primary hyperparathyroidism. Those summary statements are also part of this series.

Recommendations of the Two Summary Statement Guidelines Papers

The guideline panel conducted systematic reviews for selected critical questions on hypoparathyroidism and primary hyperparathyroidism (Table 1) and issued a total of eight GRADEd recommendations (seven for hypoparathyroidism and one for hyperparathyroidism) based on one of the reviews related to primary hyperparathyroidism and four reviews and one survey related to hypoparathyroidism. The guideline panel also issued 59 non‐GRADEd recommendations (20 for hypoparathyroidism and 39 for hyperparathyroidism) based on narrative reviews, which were labeled non‐GRADEd recommendations.

| General questions | PICO/PECO format questions |

| 1. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the symptoms and complications? This question did not directly inform a recommendation. | P: People with and without hypoparathyroidism, including both postsurgical and nonsurgical E (Exposure): Hypoparathyroidism C: People with normal parathyroid function O: Outcome or impact of hypoparathyroidism |

| 2. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of PTH therapy versus conventional therapy? | P: Hypoparathyroidism from any cause (subgroups of postsurgical versus nonsurgical) I: PTH supplement therapy C: Conventional therapy (calcium, calcitriol, or alfa calcidol) O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 3. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of using different monitoring strategies? | P: Patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism I: More frequent monitoring with variety of tests C: Less frequent monitoring, with same or different tests O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 4. In patients undergoing total thyroidectomy, what is the value of measuring PTH or calcium shortly after surgery to predict the development of chronic hypoparathyroidism? | P: Patients that underwent total thyroidectomy I/C: Measuring early PTH or calcium levels within 12 or 24 hours after surgery O: Chronic hypoparathyroidism as defined by investigators 6 months or 1 year after surgery |

| 5. In patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of surgery versus nonsurgical management? | P: Patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism I: Surgery with or without medical therapies C: No surgery with or without medical therapies O: Patient‐important outcomes: Biochemical cure, fracture, kidney stones and renal failure, quality of life, mortality, surgical complications, cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular complications. Surrogate outcomes: Fractures as inferred from bone mineral density, biochemical cure as inferred from serum calcium, serum PTH, 24‐hour urinary calcium excretion, serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate, systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure, left ventricular mass index and ejection fraction. |

| General questions | PICO/PECO format questions |

| 1. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the symptoms and complications? This question did not directly inform a recommendation. | P: People with and without hypoparathyroidism, including both postsurgical and nonsurgical E (Exposure): Hypoparathyroidism C: People with normal parathyroid function O: Outcome or impact of hypoparathyroidism |

| 2. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of PTH therapy versus conventional therapy? | P: Hypoparathyroidism from any cause (subgroups of postsurgical versus nonsurgical) I: PTH supplement therapy C: Conventional therapy (calcium, calcitriol, or alfa calcidol) O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 3. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of using different monitoring strategies? | P: Patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism I: More frequent monitoring with variety of tests C: Less frequent monitoring, with same or different tests O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 4. In patients undergoing total thyroidectomy, what is the value of measuring PTH or calcium shortly after surgery to predict the development of chronic hypoparathyroidism? | P: Patients that underwent total thyroidectomy I/C: Measuring early PTH or calcium levels within 12 or 24 hours after surgery O: Chronic hypoparathyroidism as defined by investigators 6 months or 1 year after surgery |

| 5. In patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of surgery versus nonsurgical management? | P: Patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism I: Surgery with or without medical therapies C: No surgery with or without medical therapies O: Patient‐important outcomes: Biochemical cure, fracture, kidney stones and renal failure, quality of life, mortality, surgical complications, cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular complications. Surrogate outcomes: Fractures as inferred from bone mineral density, biochemical cure as inferred from serum calcium, serum PTH, 24‐hour urinary calcium excretion, serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate, systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure, left ventricular mass index and ejection fraction. |

| General questions | PICO/PECO format questions |

| 1. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the symptoms and complications? This question did not directly inform a recommendation. | P: People with and without hypoparathyroidism, including both postsurgical and nonsurgical E (Exposure): Hypoparathyroidism C: People with normal parathyroid function O: Outcome or impact of hypoparathyroidism |

| 2. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of PTH therapy versus conventional therapy? | P: Hypoparathyroidism from any cause (subgroups of postsurgical versus nonsurgical) I: PTH supplement therapy C: Conventional therapy (calcium, calcitriol, or alfa calcidol) O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 3. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of using different monitoring strategies? | P: Patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism I: More frequent monitoring with variety of tests C: Less frequent monitoring, with same or different tests O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 4. In patients undergoing total thyroidectomy, what is the value of measuring PTH or calcium shortly after surgery to predict the development of chronic hypoparathyroidism? | P: Patients that underwent total thyroidectomy I/C: Measuring early PTH or calcium levels within 12 or 24 hours after surgery O: Chronic hypoparathyroidism as defined by investigators 6 months or 1 year after surgery |

| 5. In patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of surgery versus nonsurgical management? | P: Patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism I: Surgery with or without medical therapies C: No surgery with or without medical therapies O: Patient‐important outcomes: Biochemical cure, fracture, kidney stones and renal failure, quality of life, mortality, surgical complications, cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular complications. Surrogate outcomes: Fractures as inferred from bone mineral density, biochemical cure as inferred from serum calcium, serum PTH, 24‐hour urinary calcium excretion, serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate, systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure, left ventricular mass index and ejection fraction. |

| General questions | PICO/PECO format questions |

| 1. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the symptoms and complications? This question did not directly inform a recommendation. | P: People with and without hypoparathyroidism, including both postsurgical and nonsurgical E (Exposure): Hypoparathyroidism C: People with normal parathyroid function O: Outcome or impact of hypoparathyroidism |

| 2. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of PTH therapy versus conventional therapy? | P: Hypoparathyroidism from any cause (subgroups of postsurgical versus nonsurgical) I: PTH supplement therapy C: Conventional therapy (calcium, calcitriol, or alfa calcidol) O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 3. In patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of using different monitoring strategies? | P: Patients with chronic hypoparathyroidism I: More frequent monitoring with variety of tests C: Less frequent monitoring, with same or different tests O: Patient‐important outcomes: nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, cataract, seizures, arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, depression, infection, mortality, quality of life; surrogate outcomes: serum calcium, urine calcium, phosphate. |

| 4. In patients undergoing total thyroidectomy, what is the value of measuring PTH or calcium shortly after surgery to predict the development of chronic hypoparathyroidism? | P: Patients that underwent total thyroidectomy I/C: Measuring early PTH or calcium levels within 12 or 24 hours after surgery O: Chronic hypoparathyroidism as defined by investigators 6 months or 1 year after surgery |

| 5. In patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism, what are the desirable and undesirable consequences of surgery versus nonsurgical management? | P: Patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism I: Surgery with or without medical therapies C: No surgery with or without medical therapies O: Patient‐important outcomes: Biochemical cure, fracture, kidney stones and renal failure, quality of life, mortality, surgical complications, cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular complications. Surrogate outcomes: Fractures as inferred from bone mineral density, biochemical cure as inferred from serum calcium, serum PTH, 24‐hour urinary calcium excretion, serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate, systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure, left ventricular mass index and ejection fraction. |

GRADEd recommendations

GRADEd recommendations followed a structured process that we will describe in detail.(3,4)

Non‐GRADEd recommendations

Non‐GRADEd recommendations involved less structured approaches without formal specification of PICOs (P: Patient population, I: Intervention, C: Comparator group, O: Outcome), included conduct of traditional expert narrative literature reviews rather than systematic review approaches, and did not include tables summarizing the findings. Readers should interpret these non‐GRADEd recommendations as they would other recommendations based on traditional approaches to guideline development.

Structured Questions—GRADEd Recommendations

Evidence review

A methods team led by GG, LY, and ZY, with substantial input from expert task force members, led the five systematic reviews. The reports of these systematic reviews, included as four separate articles in this series, provide all relevant details.

Defining the clinical questions

The steering committee defined the scope of the guidelines. Each task force took primary responsibility for proposing important clinical questions for systematic review. Five questions, four for hypoparathyroidism and one for primary hyperparathyroidism, were chosen. They were subjected to a structured process that included defining the relevant population, alternative management strategies (intervention/exposure and comparator), and outcomes (i.e., PICO/PECO (P: Patient population, E: Exposure, C: Comparator group, O: Outcome) format) (Table 1). Each clinical question provided the framework for formulating inclusion and exclusion criteria for systematic reviews and guided the search for relevant evidence.

Patient‐important and surrogate outcomes

For GRADEd recommenadtions, the panel focused on outcomes that patients considered important rather than surrogate outcomes (e.g., fractures rather than bone density, renal stones rather than 24‐hour urinary calcium excretion). In the hypoparathyroidism guideline, the panel focused on outcomes suggested, in the relevant systematic review, to be clearly causally related to hypoparathyroidism.

Identifying the literature

For each PICO/PECO question, the methods team searched Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane library. Paired reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts retrieved from databases and further reviewed the full‐text articles for eligibility and resolved conflicts and disagreements by discussion. Searching the reference lists of publications of primary studies and relevant narrative reviews and guidelines provided another strategy for identifying additional references.

Assessing studies, summarizing evidence, and evaluating eligibility and risk of bias

Given the different types of questions addressed in the systematic reviews, eligibility differed: case series and cohort studies for the review of complications, diagnostic accuracy studies for the diagnostic review, and randomized trials for the comparisons between conventional therapy and PTH therapy of hypoparathyroidism, for comparisons between medical therapy and no medical therapy in primary hyperparathyroidism and for comparisons between surgery and no surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism. To assess the risk of bias of the different types of studies, the methodology team used the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for case series studies,(5) a modification of Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies,(6) a modified Cochrane risk‐of‐bias tool for randomized control trials,(7,8) and the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS‐2) for diagnostic accuracy studies.(9) Two reviewers independently rated the risk of bias, and a third senior reviewer resolved disagreements.

Evaluating certainty of bodies of evidence

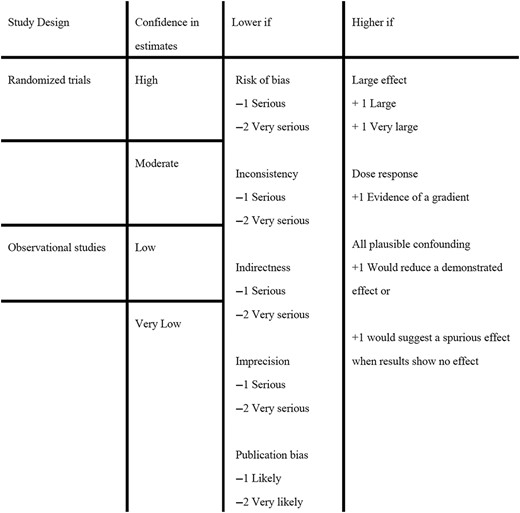

For therapeutic and diagnostic systematic reviews, the methods team rated the certainty of evidence on an outcome‐by‐outcome basis using GRADE Working Group criteria (Fig. 2). When the certainty of evidence differed across outcomes, the methods team made an overall rating as the lowest certainty rating of the outcomes judged as critical.(3)

Defining subgroup analysis and assessing credibility

In each systematic review, the task force members defined possible subgroup analyses, including hypothesized direction of subgroup effects. To assess the credibility of subgroup effects, the methods team used the Credibility of Effect Modification Analyses (ICEMAN) criteria, a structured checklist consisting of nine items addressing design, analysis, and context of subgroup analysis.(10)

Conducting meta‐analyses

We were unable to perform meta‐analyses for two reviews: the complications review (first PICO in Table 1, the extremely diverse studies made it difficult to justify a meta‐analysis to determine prevalence) and the monitoring review (third PICO in Table 1, only two studies described the monitoring frequency).

We performed meta‐analyses for the other three reviews. We used bivariate analysis to calculate the pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity for the predicting review (fourth PICO in Table 1). The other two reviews addressed management issues; the methods team used a random‐effects model for all primary analyses. Chi‐squared tests and I2 statistics provided methods for assessing statistical heterogeneity.

Summary‐of‐findings tables

For GRADEd recommendations addressing therapeutic or diagnostic issues (recommendations based on systematic reviews), we summarized the certainty of evidence and estimates of relative and absolute effects of alternative management strategies in summary‐of‐findings tables.(11,12)

Recommendation direction and strength

GRADEd recommendations followed a structured process to classify recommendations as strong or weak.(11,12) Determinants of the strength and direction of recommendations included the balance between the desirable and undesirable consequences of an intervention, the certainty of evidence, patient values and preferences, and issues of feasibility, acceptability, and equity. The recommendations were graded as strong when desirable effects were much greater than undesirable effects or vice versa. Strong recommendations were worded as “We recommend.” Recommendations were graded as weak either because of low certainty evidence or a close balance between desirable and undesirable outcomes and were worded as “We suggest.”

Conducting a Survey Addressing Monitoring in Hypoparathyroidism

The methods team found very limited discussion in the systematic review addressing monitoring in hypoparathyroidism, so Task Force 4, in consultation with the methods team, designed a survey to evaluate the practice of the international experts who constituted the task forces on hypoparathyroidism. Respondents reported how frequently they assessed a wide variety of variables, including calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium levels. The task force identified a test as useful if a minimum of 70% of respondents used the test in >70% of their patients. Based on the survey, the panel issued three GRADEd recommendations. One of the papers in this series describes in detail the methods and results of the survey.(13)

Values and Preferences

The task force members considered patients' values and preferences in all recommendations. Patient partners provided formal input to two task force cochairs (AAK and LR), who ensured the panel considered their input. Important judgments included (i) patient important outcomes over surrogate outcomes and (ii) a higher value on comprehensive assessment and detecting possible problems than on parsimonious use of tests that might minimize costs, concern, and possibly unnecessary interventions.

Costs, Feasibility, Acceptability, Equity

Because cost issues were unlikely to change the direction or strength of the recommendations, the task forces did not conduct economic evaluations to consider resource use. In making their recommendations, the panel considered feasibility, equity for all patient populations including the pediatric and elderly patient populations, and practical issues.

Finalizing the Recommendations

For both GRADEd and non‐GRADEd recommendations, the intent, successfully implemented, was to achieve consensus on all recommendations. There was no provision for voting. Chairs of each task force formulated the draft recommendations and scheduled discussions with all task force members to reach consensus. For GRADEd recommendations, the task forces reached consensus on the wording of recommendations, the level on the certainty of evidence, and the direction and strength of recommendations; for non‐GRADEd recommendations, the task forces reached agreement on expert practice.

Disclosing and Managing Conflicts of Interest

The individual disclosures of the steering committee and task force members are provided in papers in which they serve as coauthors. All panelists identified industry consultancies and advisory board memberships. Those who disclosed consultancies were not excluded. There was no other management of conflict of interest. The supplementary material includes the conflict‐of‐interest form that task force members completed. The following companies provided unrestricted educational support for the guideline process: Amolyt, Ascendis, Calcilytix, and Takeda. Although the companies were invited to attend the open sessions, they were not invited to make comments. The companies had no input into the design, leadership selection, task force membership, methods group constitution, implementation, conclusions, or the writing or review of manuscripts. The funds received were budgeted for methodology, knowledge translation, publication charges, young fellows' travel grants, meetings, and administrative costs. All members of the steering committee, cochairs, and task force members served on a voluntary basis and did not receive any financial compensation.

Internal and External Presentations

The recommendations were presented to members of all task forces in two separate sessions: one for hypoparathyroidism and one for primary hyperparathyroidism. The steering committee and task force chairs considered all comments offered at the time of the presentations. In addition, all task force members had the opportunity to comment on and edit the draft manuscripts, including systematic reviews, narrative reviews, and guideline documents, in order to provide any clarification required. The recommendations did not require any modification following the presentations and feedback received by the attendees.

The recommendations were also presented to all societies, organizations, and patient advocacy groups that expressed interest in supporting these guidelines. The two summary‐guideline papers were then distributed to all groups with invitation for comment and approval. All comments were considered by the steering committee and task force chairs. The groups that approved the guidelines emanating from this project are listed in the two summary statements. All guideline manuscripts, including this one, were submitted to the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, where they underwent peer review. The peer review process will not result in any modification to the recommendations.

Limitations

The panel commissioned five systematic reviews to address particularly important and potentially controversial questions, two of which directly addressed management issues. Thus, the guidelines included a small number of GRADEd recommendations (one for hyperparathyroidism, seven for hypoparathyroidism). Recommendations regarding monitoring informed by the panel survey are also graded, but all are weak recommendations because they were based on very low‐certainty evidence. For the remaining questions, the task forces issued 59 non‐GRADEd recommendations (20 for hypoparathyroidism and 39 for hyperparathyroidism) based on narrative reviews. Though not graded or formalized by the process of a systematic review, those narrative reviews, nevertheless, were also based upon a careful review of the literature by the task force members.

Management of financial conflict of interest was restricted to exclusion of industry employees, declaration of financial conflicts by panelists, and declaration of funding for the guideline effort from pharmaceutical companies. Neither individual panel declarations nor funding for the guideline provided any indication of the magnitude of support. The panel did not consider nonfinancial conflicts of interest.

Plans for Updating

We plan to update the recommendations when important new data that will impact the recommendations become available.

Disclosures of Interests

AAK—Grants or speaker for Alexion, Amgen, Amolyt, Ascendis, Chugai, Radius, Takeda, Ultragenyx; consultant for Alexion, Amgen, Amolyt, Ascendis, Chugai, Radius, Takeda, Ultragenyx.

JPB—Consultant for Amgen, Radius, Ascendis, Calcilytix, Takeda, Amolyt, Rani Therapeutics, MBX, Novo‐Nordisk, Ipsen.

MLB has received honoraria from Amgen, Bruno Farmaceutici, Calcilytix, Kyowa Kirin, UCB; grants or speaker: Abiogen, Alexion, Amgen, Bruno Farmaceutici, Echolight, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Kirin, SPA, Theramex, UCB; consultant: Alexion, Amolyt, Bruno Farmaceutici, Calcilytix, Kyowa Kirin, UCB.

BLC—Consultant for Takeda/Shire, Amolyt Pharma, Calcilytix; grants from Takeda/Shire, Ascendis.

MM—Consultant for Takeda, Amolyt, and Chugai; grants from Takeda and Chugai.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge unrestricted financial support from Amolyt, Ascendis, Calcilytix, and Takeda. They had no input into the planning or design of the project, the conduct of the reviews, evaluation of the data, writing or review of the manuscript, its content, conclusions, or recommendations contained herein.

Author Contributions

Design/conceptualization of project: AAK, JPB, MM, MLB, BLC, GG. Data acquisition, review, analysis, methodology: LY, ZKY, GG, AAK, JPB. Project administration, including acquisition of funding: AAK, JPB, MM, MLB, BLC. Original drafting and preparation of manuscript: LY, GG. Review/editing of manuscript: LY, GG, AAK.

Ethical Statement

The study described the methods of guideline development and did not require ethics committee approval.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jbmr.4687.

Data Availability Statement

This method study included no data.