-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Njuguna Ndung'u, Abebe Shimeles, Dianah Ngui, The Old Tale of the Manufacturing Sector in Africa: The Story Should Change, Journal of African Economies, Volume 31, Issue Supplement_1, September 2022, Pages i3–i9, https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejac016

Close - Share Icon Share

1. Introduction

Despite some recent signs of resurgence, the manufacturing sector in Africa had stagnated and has been performing poorly, lagging all other regions of the world—a trend reflecting several factors and a weak competitiveness. The share of manufacturing value added in Growth Domestic Product (GDP) declined from 16% in 1980 to less than 10% in 2016 in Africa. Similarly, Africa's global share of manufacturing value added declined from 1.6% to 0.7% in the same period. The low performance has been attributed to a range of factors including high cost of doing business, unstable political and regulatory environment, lack of long-term policy clarity, lack of infrastructure and undue dependence on natural resources as a source of growth.

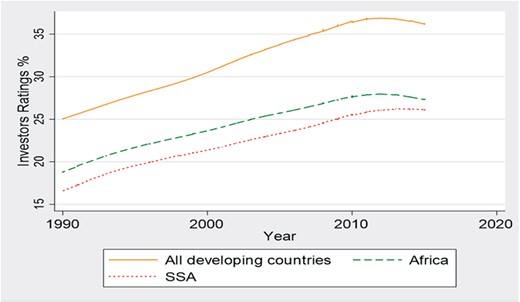

The weakness in basic institutional and economic fundamentals is evident from the perceptions of rating agencies that have graded Africa consistently below all developing countries (Figure 1). The situation is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic that exposed further the structural and institutional vulnerabilities that African economies faced for much of the past four to five decades.

Investors' Ratings of Three Different Economies: Developing Countries, Africa and SSA

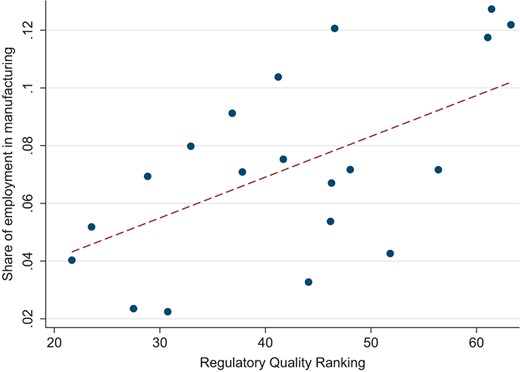

Despite the structural weaknesses, many African countries in recent years have taken several reforms to build a strong manufacturing sector, mainly learning from the experiences of China that benefitted from the establishment of industrial zones. Getting the ‘basics’ right still resonates well for Africa. Figure 2 shows that countries with better quality of the regulatory bodies tend to have strong manufacturing sector presence after controlling for differences in initial per capita GDP, human capital stock and inequality. Such strong correlation suggests the strength of quality of institutions in advancing the manufacturing sector in Africa. For the African scene, this is a powerful set of results. We need strong institutions to regulate, protect and guide the market to the optimal development path by applying the legal framework and defining appropriate incentives.

Share of Manufacturing Employment and Regulatory Quality in Africa

The traditional concerns such as infrastructure, skills, appropriate definition of property rights and regulations are still critically important. However, as noted by Newman et al. (2016), they alone will not be sufficient for Africa to industrialise. The challenges presented by the region's growing resource abundance calls for the industrialisation strategies to adapt accordingly (see Page, 2018; Page and Tarp, 2020). Thus, Africa requires diverse instruments notably industrial policies, including for agriculture and services, and a focus on learning industrial and technology [LIT] policies for developmental transformation. Africa also needs greater participation, involving a balance between markets, government and society, in addition to getting a comprehensive package of development interventions and policies including infrastructure and institutions right. These are typical issues in policy papers by governments; the risk is how they are or they are not implemented. Most firms in Africa will point out issues on tax policy design and implementation and changing or inconsistent products and input classifications. It means that these diverse policy instruments require to be opened to understand their incentive or disincentive value in their application and design.

This special issue combines three papers presented virtually during the June 2020 Plenary Session of the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) bi-annual research workshop, on the theme ‘Business Environment, Competitiveness and Economic Growth in Africa’. The objective of these papers was to unpack why Africa continues to be less competitive despite progress in the areas of doing business, investment climate and infrastructure. The focus is on how misalignments in economic policy management create distortions that impede the performance of firms, thereby reducing the growth of decent jobs. The three papers focus on two challenges of advancing manufacturing sector in Africa. The first challenge, which applies to all sectors of the economy is to get the ‘basics’ right, which emphasises the role of regulatory and institutional quality on competitiveness. The second challenge is the sector-specific policies that either favour or impede manufacturing activities. The papers by Cust et al. and Aryeetey and Twumasi Baffour focus on the first aspect of the challenge, while Gebrewolde et al. discuss a case of specific macroeconomic distortions that impeded manufacturing activities in Africa.

The first paper by Cust et al. on ‘Dutch disease and the public sector: how natural resources can undermine competitiveness in Africa’ explores the relationship between low competitiveness and high natural-resource dependence in Africa. They argue that lack of accountability by the government on the resource revenues might result in inefficient and distortionary spending ways, thereby undermining competitiveness. They observed that improved accountability could enhance the effectiveness of the public sector and hence the competitiveness of the private sector.

The second paper by Aryeetey and Twumasi Baffour on ‘African competitiveness and the business environment: does manufacturing still have a role to play?’ uses annual data over the period 2003–2018 for 41 African countries to investigate the drivers of manufacturing competitiveness in Africa. They propose enhancement of regulatory environment and infrastructure development to make the sector globally competitive with the government purposely identifying the challenges working against manufacturing competitiveness on the continent.

The third paper by Gebrewolde et al. on ‘Currency shocks and firm behaviour in Ethiopia and Uganda’ construct measures of currency shocks using matched customs and firm-level data, based on both the actual currency of invoicing and bilateral exchange rates. The paper finds that currency depreciations based on the currency of invoicing to importers in Ethiopia lower not only the likelihood of using imported inputs and the share of imported inputs for firms, but also productivity—outcomes not evident in Uganda.

2. Dutch disease and the public sector: how natural resources can undermine competitiveness in Africa

The paper by Cust et al. focuses on the relationship between low competitiveness and high natural-resource dependence in Africa. The paper begins by taking note of the long-term structural decline in the share of manufacturing value added in GDP at the regional level, which is a trend reflecting a weak competitiveness of African manufacturing relative to other regions. While taking into consideration that higher labour costs, lower population density, more costly capital, riskier political and regulatory environment, lack of infrastructure and the presence of natural resources as some of the factors that have been attributed to the weak competitiveness. The paper observes that natural resource exports are a driver of weaker competitiveness through the Dutch disease, which refers to the economy's response to a booming sector that raises consumption and attracts activities to itself at the expense of the other sectors. Dutch disease affects the relative price (appreciates the nominal exchange rate) and dwarfs the other sectors resulting to deindustrialization. This affects the resource allocation and its deleterious impact on the competitiveness of tradable sectors in the economy. The authors highlight the fact that Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries are in the bottom ranks of the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI 4.0) and have, on average, low levels of regulatory effectiveness (reflecting weak institutions), compared with other regions, according to the annual Doing Business ranking produced by the World Bank.

The authors argue that a sudden increase in public spending following a windfall of natural resource rents can distort public sector actions. They further note that the way in which governments use these additional expenditures may undermine economy-wide competitiveness captured successively with (i) exports outcomes, (ii) change of value added in agricultural and industrial sectors over time and (iii) change of GCI 4.0 score over time. Cust et al. suggest transferring a portion of resource revenues to the citizens, and then tax them to finance public expenditures—oil to cash (see Moss et al., 2010), which might lead to a better understanding of the size of government revenues and, secondly, higher scrutiny of public spending from citizens, since it is financed out of their tax payments.

The authors note potential challenges associated with the proposed ‘oil to cash’ solution, which include the following: (i) its feasibility, making transfers to a dispersed population that they argue is now subject to a technological solution. For instance, Kenyan M-Pesa, which started from a real time retail electronic payments system, has led to mobile banking enabling hundreds of millions of people to undertake financial transactions with their cell phone. (ii) The potential misuse of cash money by citizens, i.e. spending by households on alcohol, tobacco and other ‘temptation goods’—although not empirically supported. (iii) Lastly, the potential resistance by governments to the loss of discretion in spending resource revenues, a bottleneck that could be solved by the government transferring resources to the citizens and inviting them to contribute to the project's financing, with the conditions that include citizens receiving a return on their investment if the project is successful or the citizens keeping the transfer but receiving no return on the investment if the project is unsuccessful.

3. African competitiveness and the business environment: does manufacturing still have a role to play?

The paper by Aryeetey and Twumasi Baffour investigates the determinants of manufacturing competitiveness proxied by manufacturing value added as a percentage of GDP in Africa using annual data from 2003 to 2018 for 41 countries. The authors acknowledge that the manufacturing sector in Africa has been lagging all other sectors on the continent despite the fact that manufacturing transformation has been the most important source of economic growth and development in economic history. The authors further recognise that that growth in manufacturing output has been slow leading to growing skepticism about the future of manufacturing-led transformation in the region.

The paper shows that SSA lags all regions of the world: from its lowest value of about $90 million between 1995 and 2000, the value of manufacturing value added has risen marginally in the sub-region to about $166 million between 2013 and 2018. This is even though manufacturing plays a strategic role in the process of economic development including (i) being the main source of innovation in modern economies, (ii) research and development activities of manufacturing firms being an important source of technological development and (iii) offering more opportunities for employment creation being a critical demand side stimulus for the agricultural sector.

The authors argue that with enabling factors such as low cost of labour, raw materials, abundant natural resources and recent improvements in the region's infrastructure base, manufacturing-led industrialisation can still be achieved by increasing the global competitiveness of manufacturing in the region. Aryeetey and Twumasi Baffour, however, observed that Africa has substantial gaps in port, road and power infrastructure, in addition to restrictive bureaucratic processes and high levels of corruption (reflects institutional failure problems), which act to increase the cost of doing business in the continent, hence constraining growth in manufacturing for all firms especially small- and medium-sized enterprises. Despite the substantial gaps, the authors note that competitiveness in manufacturing can be boosted on various fronts including labour productivity, electric power, industrial land, movement of goods, business environment, financial systems and tariffs.

Aryeetey and Twumasi Baffour argue that the ineffectiveness of the manufacturing sector to date can be attributed to the governments not making the necessary governance and institutional adjustments. The authors find that (1) good governance is vital for manufacturing development; (2) improvement in the provision of electricity, water and sanitation, good road network and good communication technology should be considered as precondition in developing the manufacturing base and improving the competitiveness of manufacturing in Africa; (3) an appropriate exchange rate management, aimed at maintaining a competitive exchange rate, is necessary for the development of manufacturing competitiveness in Africa; (4) the importance of domestic market size and agglomeration in positively determining manufacturing development in Africa re-emphasises the need for African governments to intensify efforts of regional integration towards the creation of larger domestic markets and reduce the challenge of market fragmentation on the continent; and (5) in Africa, increase in income does not generate growth in manufactured output due to increased demand for manufactures as implied by the U-shaped relationship between GDP per capita and manufacturing share of GDP.

4. Currency shocks and firm behaviour in Ethiopia and Uganda

This paper uses data from a detailed survey of firms in Ethiopia (2012–2017) and the Corporate Income Tax Data from Uganda and PAYE data (2010–2017), together with administrative data from the Customs and Revenue Authorities in both countries, to examine the impact of firm-specific currency shocks on import behaviour and firm productivity. The authors observed that although the two countries have different exchange rate regimes, the firms are exposed to the same degree of exchange rate shocks since, on average, they use imported materials at similar intensity.

In assessing the impact of the currency shocks on firm behaviour, the authors look at three outcomes: (1) the (change in) importer status between years; (2) the change in the share of imported inputs used; and (3) whether these fluctuations have an impact on labour productivity. Gebrewolde et al. argue that currency shocks will affect firms differently depending on the currencies that their imports and exports are invoiced in and their exposure to traded inputs and outputs. Therefore, the competitive pressures induced are likely to affect firm productivity with potentially ambiguous effects.

The paper constructs firm-level measures of real effective currency shocks using data on the currency of invoicing at the firm level, which allows the authors to construct the exact impact on importers and exporters of fluctuations in exchange rates. This is contrary to most studies that use either data on currency shocks at the aggregate level or use more refined measures, combining data on trade flows to construct shocks based on bilateral exchange rates, which according to the paper remains a proxy since it does not capture the actual rate used in contracting trades. The authors observe that both countries experienced nominal depreciation in their currencies against the US$ and the Euro over the period between 2010 and 2017, noting a substantial time-series variation in the dollar exchange rate of the Birr (Ethiopia) and Shilling (Uganda), but also cross-sectional variation in exchange rates against different major currencies of invoicing.

The authors find that the exchange rate regime in Ethiopia imposes sharp costs on both the intensive and extensive margins for importers and on labour productivity, while for Uganda the floating regime allows firms to smooth the effect of such fluctuations, as there are no effects of currency shocks on either importing or labour productivity. Using measures of shocks based on the currency of invoicing, the paper finds strong effects of exchange rate shocks on importers and productivity in Ethiopia and no effects on firm-level outcomes in Uganda. For Ethiopia, the paper finds that increases in currency shocks based on the currency of invoicing lowers both the extensive and intensive margins on imports, as well as labour productivity growth. The paper concludes that Ugandan firms seem to be able to weather their currency shocks while Ethiopian firms are more constrained and must bear the burden of such fluctuations.

5. Conclusions of the papers

The three papers presented at the AERC June 2020 Plenary Session have tackled several issues relating to the theme of the plenary—‘Business Environment, Competitiveness and Economic Growth in Africa’. The studies show that the manufacturing sector in the African region has experienced slow growth due to low competitiveness that can be enhanced from different fronts, but more importantly the institutional weaknesses that induce policy failure.

Some of the key findings of the studies are as follows: first, a boom in government spending has a negative and significant correlation with export performance, agricultural value added per worker and industrial output, but it is compounded by lack of accountability. While this is evident, the quality of public spending should determine the quantity of public spending. Therefore, Governments should have effective systems to prioritise and select investment projects and adequately provide for the recurrent costs of maintenance. This would require improving the quality of project appraisal and establishing a medium-term expenditure framework that incorporates multi-year maintenance plans.

Secondly, to make the manufacturing sector globally competitive, it would be appropriate to enhance regulatory environment and infrastructure development with the Government deliberately identifying the challenges working against manufacturing competitiveness on the continent. However, it should be noted that in as far as industrial policy is concerned, each moment of time and each country is different—so policies must be adapted to the circumstances and the ever-changing times, taking due account of the history of each case.

Thirdly, the effect of the currency shocks on import behaviour and firm productivity varies with the exchange rate regime. Thus, firms operating in countries under floating regime like Uganda seem to be able to weather their currency shocks compared with those operating under weak exchange rate regime (for instance Ethiopian firms) that are more constrained and must bear the burden of such fluctuations.

The studies recommend improvement of the business and regulatory environment for enhancement of manufacturing competitiveness. As indicated by Page and Tarp (2017), for sustained success in structural transformation, there is a need for new policies and new approaches to government–business coordination, with the private sector, not the public sector, holding much of the information relevant to policy formulation for industrial development.

Funding

AERC, ME Bank Tower, 3rd Floor, Jakaya Kikwete Road, Nairobi, Kenya.