-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Manfred Elsig, Gabriele Spilker, Dealing with Clashes of International Law: A Microlevel Study of Climate and Trade, International Studies Quarterly, Volume 68, Issue 4, December 2024, sqae136, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqae136

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

For years, scholars in international relations have addressed questions related to regime complexity and its effects. However, there is a lack of understanding of how individuals react to clashes of international law obligations when assessing domestic policies. In this article, we study the extent to which citizens are concerned with compliance and noncompliance with international law when their governments design domestic laws to implement international obligations. We are, in particular, interested in whether citizens’ reactions to clashes of international obligations are driven by concerns about being exposed internationally for breaching international law or concerns about tangible material costs. Our empirical analysis is based on an experiment embedded in a survey of Swiss citizens’ attitudes toward environmental issues. The experiment first shows that individuals react to both information about compliance as well as noncompliance, whereas the shifts are more notable in the case of negative information about noncompliance. Second, we find that information about the country being subject to international adjudication (what we call exposure costs) in case of noncompliance is more consequential than information about material costs (facing retaliation).

Durante años, los académicos del campo de las relaciones internacionales han abordado cuestiones relacionadas con la complejidad de los regímenes y sus efectos. Sin embargo, existe una falta de comprensión con respecto a cómo reaccionan las personas ante los conflictos con las obligaciones del derecho internacional a la hora de evaluar las políticas nacionales. En este artículo, estudiamos hasta qué punto los ciudadanos se preocupan por el cumplimiento y el incumplimiento del derecho internacional cuando sus Gobiernos diseñan leyes nacionales que tienen el fin de implementar obligaciones internacionales. En particular, nos interesa saber si las reacciones por parte de los ciudadanos a estos conflictos de intereses con las obligaciones internacionales están impulsadas por una preocupación con respecto a ser expuestos internacionalmente por violar el derecho internacional o por una preocupación con relación a los costes materiales tangibles. Nuestro análisis empírico se basa en un experimento integrado dentro de una encuesta sobre las actitudes de los ciudadanos suizos en materia de cuestiones medioambientales. Nuestro experimento muestra, en primer lugar, que los individuos reaccionan tanto a la información sobre el cumplimiento como a la información sobre el incumplimiento, mientras que los cambios son más notables en el caso de la información negativa sobre el incumplimiento. En segundo lugar, concluimos que la información sobre el país que está sujeto a escrutinio internacional (lo que llamamos costes de exposición) en caso de incumplimiento es más importante que la información sobre los costes materiales (frente a represalias). Por último, destacamos algunas características específicas a nivel individual que se desvían de los patrones observados, incluyendo las actitudes relacionadas con el régimen, las opiniones generales sobre la globalización y los factores relativos a la ubicación.

Des années durant, les chercheurs en relations internationales ont traité des questions liées à la complexité des régimes et ses effets. Cependant, nous comprenons encore mal la réaction des personnes aux conflits avec des obligations du droit international lors de l’évaluation de politiques nationales. Dans cet article, nous étudions la mesure dans laquelle les citoyens se préoccupent de la conformité et de la non-conformité au droit international quand leur gouvernement conçoit des lois nationales pour mettre en œuvre des obligations internationales. Nous nous intéressons plus particulièrement au fondement de la réaction des citoyens aux conflits avec des obligations internationales : par souci d'exposition sur le plan international pour violation du droit international ou pour des préoccupations relatives aux coûts matériels tangibles ? Notre analyse empirique se fonde sur une expérience intégrée dans un sondage sur les attitudes des citoyens suisses à l’égard de problématiques environnementales. L'expérience montre d'abord que les personnes réagissent tant aux informations relatives à la conformité qu’à celles portant sur la non-conformité, tandis que les changements sont plus notables dans le cas d'informations négatives concernant la non-conformité. Ensuite, nous remarquons que les informations relatives à un pays soumis à une décision internationale (les « coûts d'exposition ») dans le cas d'une non-conformité sont plus importantes que celles portant sur les coûts matériels (risque de représailles). Enfin, l'on souligne certaines caractéristiques au niveau individuel qui dévient des schémas observés, y compris les attitudes relatives au régime, l'avis général quant à la mondialisation et les facteurs locaux.

Introduction

There is a burgeoning literature on regime overlap and regime complexity, but we know little about how citizens deal with information about domestic policies being consistent or inconsistent with international obligations agreed upon in different treaties or even different regimes. How do citizens rate domestic policies that might be in line with principles laid out in one international treaty but are in contradiction with commitments agreed on in another treaty? Our research note is one of the first attempts to test how citizens deal with conflicting information about international law and how this influences their perceptions.

We investigate these clashes of international law in the context of the climate regime. Not only is climate change one of the most pressing international issues of our times (IPCC 2022), but the climate regime complex, by intruding into various other international issues, is also a prime example of regime complexity (Keohane and Victor 2011). Key among the international issues with which climate change overlaps is the international trade regime (Kono 2019). One reason for this strong overlap is that among the different available policy instruments for governments to meet their (self-)defined objectives as part of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the so-called nationally determined contributions, are trade measures. Some of these measures are unilateral in nature and can, therefore, potentially create breaches of international trade law commitments as defined in the World Trade Organization (WTO). As past jurisprudence shows, some policy instruments, such as tariffs to protect domestic producers or subsidies only provided to domestic firms, are often designed in a way that is in contradiction to key WTO principles. For instance, these are the national treatment (NT) principle that foreign and domestic producers shall be treated equally, the most-favorite nation (MFN) principle that policies cannot discriminate among exporters from different countries, and that trade barriers based on domestic product processes and production methods (PPM) need to be designed in a proportional and least-restrictive way.1 Hence, a country’s effort to tackle climate change can be in conflict with its international trade obligations.2 We, therefore, argue that understanding how citizens react to information suggesting compliance and noncompliance with international law should allow policymakers to navigate better and address dilemmas of regime complexity.

Focusing on the microlevel foundations, the research note explores the relative impact of positive information related to the notion of compatibility with different international obligations versus negative information equated with incompatibility with such obligations. Building on behavioral studies in psychology, we expect that signals of some form of cost or loss for a country (and its citizens) may lead to greater shifts in public opinion than positive cues. The research note further unpacks whether citizens’ reactions to clashes of international obligations are driven by concerns about being exposed internationally for breaching international law or, in addition, by concerns about tangible material costs. Some citizens might believe noncompliance is inconsequential if international treaties resemble cheap talk and are not backed with credible compliance instruments. Other citizens, however, might trust their governments and expect signing international treaties to be self-enforcing. Therefore, revealing information regarding costs in case of noncompliance also provides context about how citizens view the authority of international law. In this research note, we aim to take a closer look at some of the underlying mechanisms that explain the key concerns citizens might have.

Relying on original survey experimental data of 2,945 individuals residing in Switzerland, our empirical analysis shows that while, in general, individuals react to cues about the state of compliance, information about noncompliance matters more than information about compliance. Furthermore, focusing on two types of informational cues, we can show that it is not so much the prospect of facing material costs of noncompliance but rather the fact of being publicly exposed in front of an international tribunal, something we call exposure costs, that matters most for affecting public support.

Literature

Three different strands of literature inspire our research note. First, we engage with the literature on regime complexity and the potential costs that can be a result of overlapping regimes. Whereas regime complexity and overlap can be observed across many fields of international relations, the literature has focused substantially on "trade and" questions (Alter and Meunier 2009; Alter and Raustiala 2018).3 While the literature discusses both the costs and benefits of regime complexity (Hofmann 2019; Henning and Pratt 2023), our research note particularly addresses the cost side of regime overlap. One special concern has been how states navigate increasingly complex legal commitments (Drezner 2009; Eilstrup‐Sangiovanni and Hofmann 2024) and whether states engage in forum shopping (Busch 2007; Panke and Stapel 2023), which tends to favor more powerful states. While more recent studies on regime complexity in trade commitments suggest that costs arising from regime complexity might be overstated (Allee, Elsig, and Lugg 2017), the evidence on the degree to which states factor in costs and benefits remains mixed.

When turning from state behavior to the microlevel, we know little about how citizens react when confronted with information about regime complexities, in particular in situations when international law obligations clash and costs might arise. This particular lack of attention to microfoundations is surprising, given that public opinion plays an important role in democracies when it comes to formulating policies and how these are situated within the realm of overlapping international law instruments. In addition, public opinion research is increasingly focusing on individual perceptions vis-à-vis international law and courts to understand the factors shaping citizens’ support in terms of authority and legitimacy of international law (Voeten 2013). Citizens might have different views when confronted with regime complexity questions that tend to produce costs. They might prefer governments to exploit regime overlap and prioritize certain legal instruments (conflictual approach), or they might opt for more cooperative approaches by supporting compliance-seeking domestic policies. Finally, citizens might observe how international courts deal with compliance across regimes while courts themselves factor in citizens’ preferences when adjudicating, showing the importance of public opinion (e.g., Harsch and Maksimov 2019).

The second strand of literature to which this research note connects relates to questions of compliance with international law more generally and what factors drive states’ propensity to comply with international law. Some of the earlier compliance studies pictured high levels of compliance as a positive development (Chayes and Chayes 1995). More recent work found that compliance with international law to be overrated as enforcement mechanisms are generally weak and because states self-select into international agreements (von Stein 2005; Spilker and Böhmelt 2013), as states often sign agreements that they are able to comply with ex ante anyhow (Downs, Rocke, and Barsoom 1996). Much of the literature has taken a state-centric approach where compliance is about the reputation of being a reliable long-term partner in cooperation (Downs and Jones 2002). Guzman (2008), for his part, has conceptualized reputation costs explicitly alongside concerns about reciprocity or retaliation as factors influencing compliance, both of which may discourage the violation of international law. Turning to domestic-level explanations, Simmons (2009) has contributed in her work to our understanding of compliance with international law by pointing to the importance of domestic institutions. She, in particular, singles out social mobilization as a major factor. More recent work has further shown that compliance can mobilize groups with different interests (Pelc 2013; Chaudoin 2014a). Our work speaks to this literature by investigating how domestic audiences value different consequences of noncompliance with international law: Is the mere fact of seeing one’s own government being labeled as noncompliant enough for citizens to perceive this negatively, or do individuals rather react to material retaliation costs? A better understanding of this question seems crucial, as mobilizing domestic audiences should at least partially depend on how citizens evaluate compliance with international commitments and which factors matter for these preferences.

Third, the research note speaks to the microlevel support for international law more broadly defined. There is emerging work striving to better understand which segments of society support international law and, therefore, the compliance with commitments entered into. One of the first sets of survey experiments studying how citizens react to (non)compliance was conducted by Tomz (2008). In his study on US citizens’ support for an import ban on products from Burma, he compared the relative effects of different moral, economic, and compliance-with-international-law-related arguments. He found substantial support for international law to matter and to shift citizens’ perspectives. Some recent work, also relying on survey experiments, has focused on how citizens assess the reputational costs of government decisions. Brutger and Kertzer (2018), for example, study the US public’s reading of US foreign policy decisions. They find that citizens have a “taste” for reputation but that the support diverges when analyzing whether individuals are more in favor of a hawkish or dovish foreign policy. They assume that the way individuals think about reputation is either top-down (through elite cues) or based on existing preconceptions. Testing both elite cues and messages about domestic policies contravening international law, Strezhnev, Simmons, and Kim (2019) find that the effect of information about international refugee law was modest in the three countries studied, but counter-endorsement by elites for the need for restrictive refugee laws could not wash out these effects either.

Our work builds on the above literature by addressing the microlevel of support for international commitments in situations where these are found to be in violation of another set of commitments. How do citizens deal with such information, i.e., how much do cues about domestic measures being in compliance with one legal instrument but not with another affect citizens’ attitudes?

Argument

How do individuals react to domestic laws’ compatibility with international law (or lack thereof) in areas where regimes overlap? Our theoretical argument is based on the assumption that citizens generally expect governments to value the international commitments they enter into. The idea that the general public assumes the government to be in compliance with international law has been strongly promoted in audience cost theories (Fearon 1994; Smith 1998). This should apply, in particular, to treaties that states have voluntarily signed. Therefore, information about compliance with international treaties should be in line with the baseline expectation most citizens hold with respect to their government’s foreign policy behavior. Or formulated differently, we assume that citizens generally expect their governments to honor their international obligations most of the time.4 Providing further attention to this aspect, though, could increase support for domestic measures as it gives a policy instrument further credibility and is a signal of a potentially successful policy.5

The flip side of this argument, however, is that citizens who are exposed to information about noncompliance should be lowering support for the respective policy instruments. Especially so, since this information should be against the expectation of most citizens, as they should assume their governments to comply in the first place. This should also shift the burden on governments to legitimize measures that clash with international law commitments. Taking a recent example, we observe the UK government in great need to legitimize its actions after having introduced a bill that did not comply with the international commitments stipulated in a treaty with the EU (Northern Ireland Protocol).6

But which information should matter more? Information on compliance or noncompliance? We expect negative information about noncompliance to shift positions relatively more than positive information, i.e., highlighting that a government is in compliance. Based on the seminal work by Kahneman and Tversky (1979), a plethora of studies have shown that individuals assign more weight to negative information than to equivalent positive information (e.g., Fridkin and Kenney 2004; Soroka 2006). The reason being that most individuals try to avoid potential losses when making decisions. In the context of international trade, this argument is in line with Pelc’s (2013) work on trade disputes, in which he shows that US citizens get mobilized when their own government is accused of trade violations, i.e., in a situation when potential losses of trade might occur. This mobilization is much stronger than in a case where a government challenges other governments regarding violations of international trade law, i.e., in a situation when potential gains from trade disputes might arise. Therefore, the first general hypothesis addresses the (relative) reactions when citizens are confronted with conflicting information about compliance with international law as a potential dilemma in situations of overlapping regimes (Alter and Meunier 2009).

Information about a policy measure to be in compliance (noncompliance) with international law increases (decreases) the support of individuals for this measure. However, the relative shift is greater for information on noncompliance than for information on compliance.

Building on the above, we now delve into more detail with respect to the precise mechanisms by which negative information about domestic policies clashing with other international obligations concluded by a government affects citizens’ evaluation. In particular, we elaborate on the question of which concerns could drive the reaction when learning about one’s own government being in noncompliance with international law. The literature has offered various explanations with different underlying assumptions as to why noncompliance might matter for individual citizens.7

If a person learns about a government measure being in noncompliance with international law, it could trigger several reactions: moral concerns, concerns about losing standing as a trusted member of the world community, fears about the future prospects of cooperation, or general disappointment that the government does not fulfill an obligation it voluntarily accepted. In their work on asylum policy, Sheppard and von Stein (2022) explicitly differentiate concerns about breaking international law, reputation concerns, and moral concerns.8 They show that information about a general breach of international law is more important than either information about losing international reputation when sidestepping international obligations or moral concerns about domestic policies in this particular area. This suggests that the news of breaking international law in itself seems more impactful than information highlighting international reputation or moral concerns. In other words, their work shows that a more generic framing of breaking international law matters more than any other specific concerns. This might not be so surprising, as the broad signal of noncompliance might already capture a number of multiple concerns, including reputational and/or moral concerns. Yet, also, regime-specificity should matter. While moral concerns for breaching international humanitarian law might be important, they probably do not exist to the same degree if states breach international trade law where other concerns might be more dominant, such as effects on future cooperation.

In line with Sheppard and von Stein (2022), we posit that general mechanisms, such as a preference for compliance with international law, might be more consequential than more specific ones, e.g., reputational costs or moral costs, for triggering citizens to negatively evaluate noncompliance. We suggest that two specific concerns could be of particular importance for citizens when confronted with information about noncompliance. We discuss each of these mechanisms in turn and formulate a corresponding hypothesis.

First, we introduce a concept that encompasses a set of nonmaterial concerns that we label “exposure costs.” These are costs that occur when countries are called out for allegedly breaking international law. In this case, credible negative news will spread pushed by international organizations’ institutionalized processes that emphasize the lack of compliance. Such specific information about being exposed as a wrongdoer might push some citizens to exhibit concerns about loss of reputation as a trustworthy member of the international community. It may also come as new information, i.e., a surprise, to citizens and lead to dissatisfaction that their own government would break international law seen as a moral duty or raise broader concerns about the credibility of international law being undermined.

But how can international institutions provide credible information that can trigger such exposure costs? This calling out or exposure can take different forms of information in view of supporting the implementation of international treaty commitments. These may range from instruments based on reporting and monitoring systems (independent evaluations, league tables, and rankings) to various forms of dispute mediation and resolution. The different tools are mainly used for shaming and exposing some form of wrongdoing. In the following, we concentrate on what is potentially the strongest form of exposure, namely when countries face public proceedings through international courts or tribunals. Being publicly singled out as breaking international law in front of an international court or tribunal is, in our view, the most extreme case that could lead to significant exposure costs and should, therefore, constitute the most likely case for citizens to react to exposure costs. We, therefore, expect information about a government being accused of noncompliance and potentially facing a public hearing in front of an international tribunal to lead to a particular negative assessment by ordinary citizens. From above, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Support for a policy measure decreases when individuals learn that noncompliance is likely to result in international court proceedings (exposure costs).

A second concern citizens might have, especially with regard to international treaties where reciprocity is an important feature, is the possibility of other treaty partners not just appealing to an international court but actually engaging in retaliation, leading to some (diffuse) forms of costs or negative material effects. The information of being party to a dispute at the international level does, in our view, not yet signal actual material costs for states.9 Yet, noncompliance could lead to a breakdown of cooperation, with negatively affected countries deciding to retaliate in some form against the state that is in noncompliance. Moving from cooperation to noncooperation usually entails welfare losses of some form. This is clearly the case in the trade regime, where retaliation is the last resort if a country refuses to take back its protectionist trade measures despite being requested by the dispute settlement body to do so. In the WTO, it happens in less than 9 percent of the cases.10

Yet, the possibility exists. Therefore, we argue that specific cues about material costs, in addition to mere information about noncompliance with the potential to face international scrutiny through courts, should, therefore, additionally decrease support for these domestic measures. The reason being that in such a situation citizens should not only take into account exposure costs as argued above but should, in addition, also negatively reward the economic costs of noncompliance.

Support for a policy measure should further decrease when individuals learn that noncompliance results in material costs due to retaliation in addition to international court proceedings (exposure costs).

Finally, we are aware that individual characteristics may condition how cues about inconsistency with international law are perceived. Chaudoin (2014b) shows in a survey experiment in the area of trade cooperation that audience costs, defined as the wider public penalizing governments for actions inconsistent with international law obligations, are conditioned by previously held beliefs by individuals about the trade policy direction. He argues that, in particular, respondents with less firm opinions are reacting to prompts about international law since respondents with strongly held opinions are less likely to change their minds in light of new information. In other words, audience costs are mainly observable among largely undecided voters but may have less impact among those with strong beliefs concerning the respective subject. Chilton and Versteeg (2016) show in their study on torture that cues about international law seem not to matter for US citizens in general but only for the subgroup of democrats. Based on these contributions, we would expect that the initial preferences of individuals in the clashing policy areas that we study should impact the magnitude of effects for both concerns about exposure as well as material costs.

Information about the lack of compliance with international law will be of higher concern for those who believe strongly in the underlying norms in the affected policy area.

Empirical Analysis

In order to test our hypotheses, we rely on an original survey experiment answered by 2,945 individuals residing in Switzerland. The survey experiment was part of the 2020 Swiss FORS MOSAiCH survey.11 We decided to rely on a survey experiment since an experimental approach allows us to causally investigate whether individuals respond differently to policy measures that are in compliance or noncompliance with international law. By randomly providing individuals with information on whether specific policy measures to implement existing obligations defined in one regime, in our case the climate regime, are or are not in line with international law obligations from another regime, in our case the trade regime, we can estimate how much individuals react to clashes of international obligations, how they are overall concerned with compliance with international law, and where these concerns are coming from.

We chose to conduct our experiment in Switzerland because we consider Switzerland to be a particularly illustrative case for a variety of reasons. First, the Swiss government, over many years, has actively supported both the trading and climate regimes. The country is highly dependent on frictionless trade as it is a small, open economy. Also, citizens have a high degree of awareness about the contribution of international trade to overall GDP, as this is a constant topic in political debates and in the media. Importantly, in contrast to other countries in Europe that are part of the European Union, the Swiss government is solely responsible for its trade policy and thus can be sued as a single actor via the WTO dispute settlement system. This is important in order for our treatment scenarios to be realistic. Furthermore, as a high-income country, its citizens also show high levels of support for climate concerns. So, both regimes seem highly important. Second and related, Swiss foreign policy builds substantially on multilateralism and international law. Both international trade law and climate law are seen as important, and the official policy has been that Switzerland is a leader and sponsor in both regimes. Switzerland hosts in Geneva the WTO and has been very active in the climate talks. Third, the knowledge of citizens is comparatively high when it comes to foreign policy, as in a system of direct democracy, citizens are periodically asked to form opinions about trade and the climate. For instance, Swiss citizens were asked in 2021 to vote on approving a trade agreement with Indonesia. While the Paris Agreement on Climate Change was not the subject of a people’s vote, a recent referendum on a new package of climate measures (called CO2 law) to implement Swiss pledges made in the Paris Accord was also highly politicized. Therefore, we assume that respondents have an above-average understanding of the questions addressed in the survey and know of the existence of international legal instruments. In summary, Switzerland provides an optimal, i.e., most likely, testing ground to study compliance with and clashes of international law.

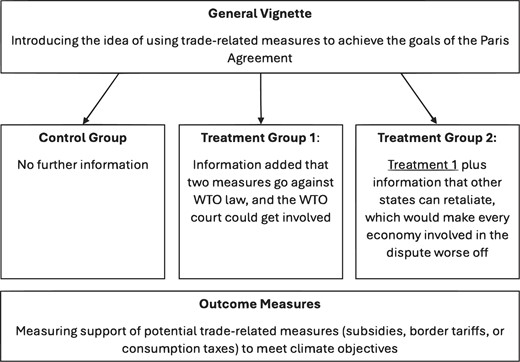

The survey experiment consisted of two parts: First, we provided all respondents with a short piece of information explaining that in order to reach the aim of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, Switzerland needs to enact certain trade-related measures. We listed three specific measures: a border tax on all CO2-intensive imports, a general tax on both CO2-intensive imports but also on domestic CO2-intensive products, and a subsidy on domestic climate-friendly products. We then randomly allocated respondents into a control group, which did not receive any further information, or one of two treatment groups.

The first treatment group received the additional information that two of these three measures, the border tax as well as the subsidy, are incompatible with WTO law as well as the information that this could potentially lead to a legal case launched against Switzerland at the WTO, thus signaling clear exposure costs. The second treatment group received the very same additional information as the first treatment group and, in addition, was told that other WTO members could retaliate economically in case Switzerland opted for either one of the two WTO-incompatible policy measures. This additional signal about clear material costs was designed to capture how much respondents care about material costs in addition to exposure costs (i.e., in addition to making Swiss noncompliance visible through a high-profile dispute).12Figure 1 illustrates the setup of the experiment.13

After reading the information, all respondents were asked to rate the three different measures (border tax, general tax, and subsidy) on a five-point scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. These three outcome measures serve as our three dependent variables in all analyses below. More precisely, we asked respondents how much they agree or disagree with each of the following statements: (i) The government should put extra taxes on products that are climate-damaging, irrespective of their provenance. (ii) The government should subsidize domestic products that are especially climate-friendly. (iii) The government should put extra tariffs at the border on foreign products that are climate-damaging.14

Importantly, both treatment groups thus received compliance and noncompliance information as a bundled package. We combined information about the two WTO noncompatible measures and the one WTO-compatible measure in our treatment texts. While we reminded respondents in the question texts which measures are compatible with WTO law and which are not, we still need to assume that reading about two of the measures being in noncompliance does not carry over to the other measure that is in compliance. Since pretesting showed that respondents can make this distinction, we are confident this assumption holds.

Results

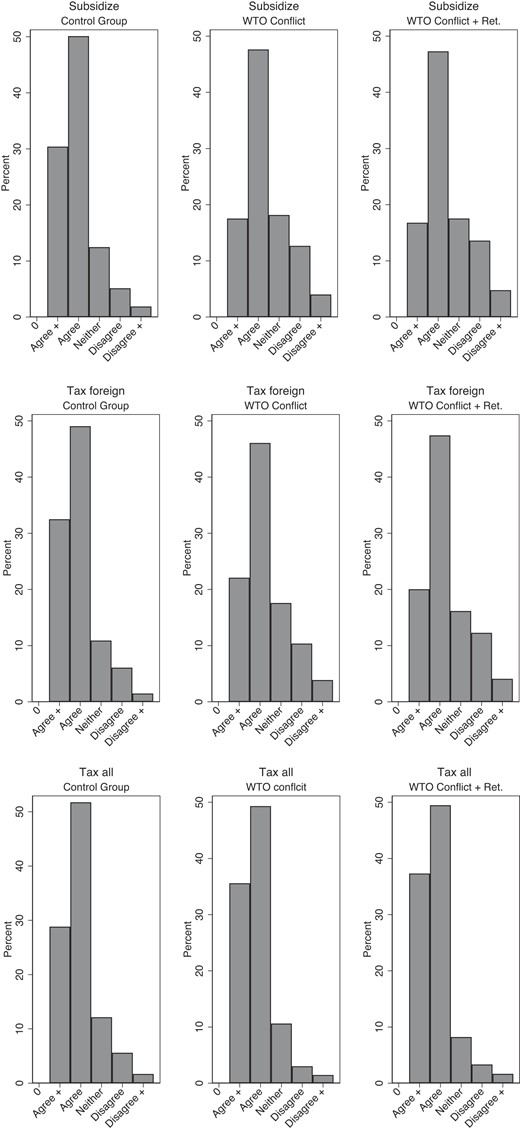

We begin the discussion of our results with a descriptive overview of support levels for the three types of policy instruments. Figure 2 shows a histogram for each policy measure ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree for the control group as well as for the two treatment groups. If we look at the first subfigure in each of the rows, we see the support levels for those individuals who were in the control group, which one can treat as a measure of baseline support/opposition toward the three policy measures since individuals in the control group did not receive any additional information. It becomes apparent that the vast majority of respondents support or even strongly support the three policy measures, and only a tiny minority of less than 10 percent oppose or strongly oppose these policy measures. This implies that any of the three policy measures to implement the obligations of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change enjoys very high levels of support.15

Support levels of different policy measures by treatment group

Furthermore, we can observe from figure 2 that this generally high support somewhat decreases for the two policy measures, for which we tell respondents in our first treatment group that these measures are incompatible with WTO law—border tax and subsidy—but slightly increases for the “tax all” measure, which is WTO compatible (see second subfigure in each row). This is in line with our hypothesis that providing individuals with information that two of these measures are in contradiction with international trade law (i.e., involve exposure costs through a potential international dispute at the WTO) shifts individuals’ support levels for these measures. If we look at the third subfigure in each row, we can further see that respondents also devalue these policy measures if we tell them in addition that trade partners are allowed to retaliate economically if Switzerland uses any of the WTO-incompatible trade measures (highlighting both exposure and material costs).16

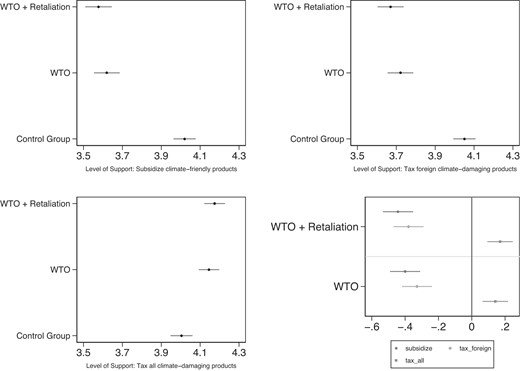

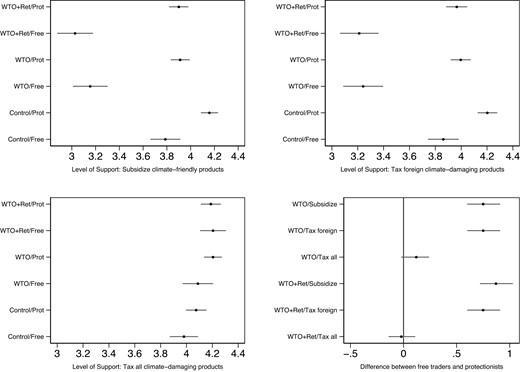

In the next step, figure 3 displays two types of information: Panels 1–3 in figure 3 show the marginal means with the corresponding 95 percent confidence intervals for each treatment group, WTO and WTO + Retaliation (with the latter containing the additional information on retaliation), as well as for the control group for each policy measure (tax on all climate-damaging products, tax on foreign products only, subsidy of climate-friendly products). Panel 4 combines and synthesizes this information and shows for each of the three policy measures the average treatment effect for the two treatment groups, WTO and WTO + Retaliation, in comparison to the control group based on an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, with the control group being the baseline category.

Main treatment effects. Note: Graph displays for panels 1–3 (upper left corner to lower left corner) mean levels of support and 95 percent confidence intervals and for panel 4 (lower right corner) coefficients with 95 percent confidence based on OLS regression with the control group as the baseline category.

Three findings shown in figure 3 seem noteworthy: First, providing individuals with information that a specific policy measure clashes with international law clearly and significantly reduces support for it, as both the reduced mean values and the negative coefficients on both WTO (Exposure) and WTO (Exposure + Retaliation) on the two WTO-incompatible measures (subsidy and border tax) show. When looking at panel 4 in figure 3 in particular, we see that both coefficients are statistically significant and point to a substantial reduction of about 0.4 points on our 1–5 scale.17 Thus, the first part of hypothesis 1, stating that information that a domestic policy measure is (not) in compliance with international law should increase (decrease) the support levels, is clearly confirmed.

Importantly, however, information not only induces individuals to decrease their support for the two WTO-incompatible measures but also induces individuals to significantly, though only marginally, increase their support for the one WTO-compatible measure, which is to tax all climate-damaging products. Therefore, the first part of hypothesis 1, namely that individuals should award policy measures that are in line with international law with higher support levels but reduce support for measures that are in noncompliance, receives support.

Second, and in line with the second part of hypothesis 1, individuals indeed reduce support more when reading about negative information concerning noncompliance (almost twice as much) as compared to how much they increase support when reading about positive information concerning compliance. This phenomenon of individuals reacting more strongly to negative information as compared to positive information (on WTO compliance in our case) is, as discussed in the theory part above, well aligned with existing literature on trade preferences (e.g., Pelc 2013; Spilker, Nguyen, and Bernauer 2020).18

Third, while this negative shift in response to the information on noncompliance is noteworthy, panels 1–3 in figure 3 also clearly show that the overall high degree of support for climate measures stays intact. This means that even if citizens learn about a measure being in conflict with Switzerland’s trade obligations, citizens still support this measure on average (despite less so than had they not known about this clash of international law).

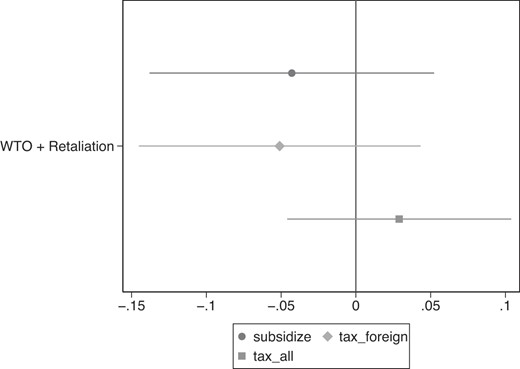

Next, we turn to hypotheses 2 and 3 and thus to the question of whether individuals mainly react to the actual fact of finding out that their government is publicly accused via an international tribunal of noncompliance or whether they put an additional value on retaliation, i.e., the fact that the breach of international law can have material consequences. From figure 3, we can already see that the confidence intervals for both WTO and WTO + Retaliation overlap—a first indication that citizens do not seem to put an additional value on material costs on top of the exposure costs that arise via a WTO dispute anyway. Figure 4 shows this more accurately by plotting the coefficients for the WTO + Retaliation treatment in an OLS regression with the WTO treatment as the baseline category. It becomes apparent that for none of the three policy measures it seems to make a difference whether, in addition to the negative information that a specific measure is in contrast to international law and the attached exposure costs, there might also be economic losses attached to the policy measure.19

Marginal effect of WTO + Retaliation treatment in comparison to WTO treatment. Note: Graph displays coefficients and 95 percent confidence intervals based on linear regression.

Finally, we test hypothesis 4, which states that our treatments should elucidate different reactions if we consider respondents who have strong attitudes vis-à-vis the affected policy areas.20 To this end, we rely on two different questions in our survey: one asking respondents about their support for international trade21 and one asking respondents whether they favor climate action or not.22 This should condition the reaction to information about clashes of norms because we expect that those individuals who hold strong attitudes should be less likely to react to information.

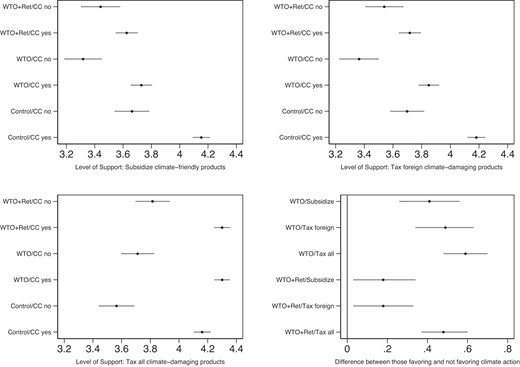

Figures 5 and 6 display the results that differentiate between the respective subgroups. Both figures are composed of four panels each: The first three panels show the mean support levels per policy measure differentiated by both treatment and subgroup (free traders versus protectionists for figure 5 and those favoring and those who are against climate action for figure 6). Panel 4 then shows the difference between the respective subgroups for the two treatments and per policy measure. This last subfigure, thus, allows us to judge whether the two subgroups indeed show significant differences.

Results differentiated by supporting or opposing free trade. Note: Graph displays for panels 1–3 (upper left corner to lower left corner) mean levels of support and 95 percent confidence intervals, and for panel 4 (lower right corner), the respective difference between the two groups of those pro and against free trade for each treatment and outcome measure.

Results differentiated by supporting or opposing further climate change action. Note: Graph displays for panels 1–3 (upper left corner to lower left corner) mean levels of support and 95 percent confidence intervals, and for panel 4 (lower right corner), the respective difference between the two groups of those favoring and not favoring climate action for each treatment and outcome measure.

Overall, the two figures show that results are rather stable in terms of effect direction if we consider different subgroups, but not necessarily in terms of effect size. Beginning with figure 5, we can observe that only one minor aspect differs from the general results discussed above in terms of effect direction. If we consider individuals who favor international trade, the results show that telling them that taxing all climate-damaging products is in line with international law no longer leads to a significantly positive effect. However, if we compare the effect sizes between free traders and protectionists for the two incompatible WTO measures (subsidies and border tax), we see that the reduction in support is significantly more pronounced for the free traders. Thus, it seems that protectionists, while reacting to the information in similar ways to free traders, react less strongly to this information. This is not surprising as protectionists generally like border measures (e.g., tariffs) or subsidies as tools of potential domestic industry protection, whereas free traders are less likely to support such measures to begin with.

Moving to the differentiation between those who favor state action on climate change and those who do not, we see that some differences exist too. While the results for those individuals who favor state action on climate change are identical to those shown above for all respondents, we see some differences for those who do not favor state action on climate change.

For those who do not support state action on climate change, we observe that compliance with WTO rules has a significantly less pronounced effect compared to those individuals who favor state action on climate change (see the second panel in figure 6 in the top right corner). For these individuals, learning that a policy measure that would tax all climate-damaging products would be in line with WTO rules hardly matters. One explanation for this finding might be that these individuals are, in any case, not in favor of using trade measures to reach climate goals (since they do not agree with the overall goals in the first place). Telling these individuals that such measures are not in line with WTO rules and might even result in retaliation might thus have little additional explanatory power.

Robustness Checks

In addition to the analyses presented in the previous section, we tested whether our results differ for various types of subgroups in our sample. Most importantly, we can show that the results are stable across various individual-level characteristics, such as gender and education, that have been shown to matter strongly for both trade and climate attitudes (Nguyen 2017; Nguyen and Spilker 2019; Umit and Schaffer 2020; Schaffer 2024). Another important factor could be how much a person is actually exposed to trade (Schaffer and Spilker 2019; Walter 2021). While our data does not allow us to identify the precise sector in which respondents work, we nevertheless have various other measures—such as whether someone is already retired, works for the public sector, or works for a nonprofit organization, all of which should be shielded from trade exposure—that let us assess this component. Furthermore, our results are robust to differentiating whether respondents hold cosmopolitan attitudes or live in urban versus rural areas (Kenny and Luca 2021). The respective figures are shown in the online appendix.

Conclusion

How do individuals react to information that certain domestic policy measures intended to implement international commitments in one policy regime are or are not in compliance with commitments agreed upon in other regimes? This research note has addressed this question by relying on a survey experiment embedded in a large national survey on attitudes toward the environment in Switzerland. The experiment builds on a realistic clash between climate and trade obligations that many countries currently face. While we in general find that individuals react to cues about (non)compliance, our results clearly show that information about noncompliance matters far more than information about compliance.

Furthermore, the evidence suggests little support for material costs of noncompliance to matter in the context studied. While future research might want to explore in more detail the degree to which respondents integrate future retaliation effects already when confronted with information about courts, we find this result particularly puzzling. A partial explanation for this finding could be that information about countries being worse off because of retaliation might not yet provide a sufficient and clear signal of how the individual respondent, or the groups they care about, are concretely affected. Notwithstanding potential refinements and extensions, the findings provide noteworthy evidence that Swiss citizens consider exposure costs when confronted with a regime-complex dilemma.

The results are instructive, in particular when thinking about a mix of policy instruments governments have at their disposal and trade-offs between the different measures. It might be possible that an argument on the noncompatibility or compatibility of domestic measures with international law could affect the overall support these measures received among voters. Therefore, when a government has to decide on priorities, it might well choose a measure that is both compliant with WTO and climate law (e.g., a general CO2 tax) rather than a measure that leads to a clash of international law (e.g., subsidies).

Going forward, it would be interesting to further unpack the dimensions of “exposure costs,” as being called out by an international body to be in breach of international law can lead to different nonmaterial concerns among individuals. What specific concerns are triggered when citizens hear about their country being in the spotlight as a wrongdoer? How do we differentiate reputation concerns from preestablished beliefs by people to uphold an internationally agreed norm, as people might simply think this is the right thing to do (“pacta sunt servanda”)? Also, weaker forms of exposure instruments (e.g., monitoring) could be directly compared with stronger forms of exposure instruments (e.g., being drawn into litigation) to provide a more nuanced picture of the types of instruments and perceived costs.

Similarly, more attention may be placed on costs to implement trade-related climate measures domestically as these also impact the overall support. In other words, comparing hypothetical international-induced costs (retaliation costs) with more tangible distributional costs at home (e.g., the costs of implementation of the domestic measures at the level of households) can help further improve our understanding of these cost aspects.

Footnotes

On the NT principle, the MFN principle and the PPM rule, see, for instance, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/envir_e/envt_rules_gatt_e.htm.

The conflict could also be going in the other direction. A country’s efforts to increase trade flows through industrial policy could lead to carbon shifting that is in conflict with international climate obligations as stipulated in the climate regime’s overall objectives to reduce CO2 emissions. It might also not adhere to the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities (see also Presberger and Bernauer 2023).

For a recent exception, see the Special Forum on International Regime Complexity in the Review of International Political Economy (Henning and Pratt 2023).

We do not assume “insincere ratification” where governments enter into international agreements with commitments they do not plan to respect, see Chilton and Linos (2021).

On signalling, see Goodman and Jinks (2004), Chilton and Linos (2021).

In order to do so, the government has put forward a principle called “doctrine of necessity,” which, however, was assessed rather critically. Opposition to enact a domestic bill that would not be in compliance with international treaties also has been visible among members of the governing party. MP Stephen Hammond was quoted: “Many colleagues are very concerned that this bill will breach international law and the commitments we have freely entered into.” Similarly, MP Sir Roger Gale stated: “The legislation appears to be in breach of articles 26 and 27 of the Vienna convention on international treaties ratified by the UK in 1971. I don’t see how I or any member of parliament can vote for a breach of international law.” The Guardian, June 15, 2022.

For an overview discussion on explanations applying survey experiments, see Chilton and Linos (2021).

In doing so, they address a gap in the literature, namely to disentangle moral from reputation costs (see Putnam and Shapiro 2017).

An important exception where direct costs may matter significantly are investor-state-arbitration disputes (ISDS) found in international investment treaties. In such proceedings, states that are facing legal complaints from investors run a considerable risk of paying monetary compensations for noncompliance. This, together with the fact that firms can sue other states, has led to ample criticism and reform of the system. In other policy regimes, dispute settlement is usually government-to-government and material costs (beyond legal costs for participation) are limited.

From overall 615 WTO cases (where consultation requests started), 91.7 percent resulted in outcomes that did not include retaliation and therefore no material costs for the defendant party. In the large majority of these cases, the measures were either withdrawn or some settlement was reached. In other words, from the universe of WTO cases starting only 8.3 percent were subject to compliance proceedings where the winning party challenges that the measure is still to some degree in place, which eventually can lead to the WTO compliance panel to authorize suspensions (we have witnessed so far forty such cases, so in total 6.5 percent), see www.wto.org.

The Swiss FORS MOSAiCH surveys allow researchers to apply for survey space. We, therefore, submitted our experimental module in 2019 and got accepted to the survey. Since we had to apply with a precise research question, clearly stated hypotheses, and a corresponding experimental design, this application serves a corresponding purpose as a preregistration. Importantly, while we spelled out the first three mechanisms of how compliance information should affect individuals’ policy support, we did not preregister hypothesis 4. Our application to MOSAiCH is part of the online appendix. The survey was conducted between 04.02.2020 and 01.08.2020 and had an overall number of 4,281 participants. Of these participants, only 3,083 respondents provided valid responses in the second part of the survey, in which our experiment was located. This resulted in a total of 2,945 respondents who fully answered our module.

While we make explicit in the second treatment that material costs can arise in the case of noncompliance, we do not provide a precise estimate of those. This is simply due to the fact that retaliation in the context of the WTO implies governments levying additional border duties to counter the costs that arose from the protectionist behavior of the other country. Yet, these costs (i) vary strongly from dispute to dispute and country to country, and (ii) while in the end borne by consumers, arise mainly at the level of firms and thus are hard to quantify in one exact number for the respective country, as would be needed for our treatment.

We decided not to design separate cues for exposure costs and material costs. In the example chosen closely related to real-world practice, there is no option to have just a court procedure (which would end with mostly reputational costs) and direct application of retaliation measures without going through the court procedure at all. This would have been possible in the GATT era when court decisions could have been simply ignored.

Since pretests showed that some respondents had difficulties remembering which measure is and which is not in line with the WTO, our outcome measures in the two treatment groups stated this again. In particular, the wording of the outcome measures for the treatment groups was as following: The government should subsidize domestic products that are especially climate-friendly, even though this is in conflict with international trade law. The government should put extra tariffs at the border on foreign products that are climate-damaging, even though this is in conflict with international trade law. The government should put extra taxes on products that are climate-damaging irrespective of their origin, which is in accordance with international trade law.

Clearly, these high levels of support could be a function of confirmation or social desirability bias. However, as we are conducting a survey experiment and randomize who receives an additional treatment, we are first and foremost interested in the differential effect of receiving additional information on compliance. Therefore, a potential confirmation bias should not affect the internal validity of our results.

We abstained from working with scenarios to break down material costs further to the level of industries or households. This would be an important further extension to investigate concerns related to direct material costs.

If we dichotomize our dependent variables and code everyone answering agreeing or strongly agreeing as 1 and everyone else as 0, we observe about a 90 percent agreement with all three policy measures in the control group. Our treatments then reduced support by slightly more than 20 percentage points for the two WTO-incompatible policy measures, suggesting a substantive effect.

We thank one reviewer who pointed out that the formulation in our control group suggests a priori that measures are in line with the Paris Agreement. Therefore, respondents in the control group might have already been cued about compliance and thus might react less pronounced to an additional information about (double) compliance, this time with the trade regime, while the cue about noncompliance provides more additional information. This could partially explain the differing effects.

We cannot rule out that some respondents already factor in material costs when they receive information about exposure costs, i.e., in the treatment group without explicit information on retaliation. This could partially explain how little additional references to material costs might matter for individuals. However, we know from the WTO caseload, that disputes lead seldomly to material costs for the noncomplying party. In other words, the material costs are a possible outcome of court proceedings, but the probability is rather low in such disputes.

This hypothesis on heterogenous treatment effects has not been part of the original application for our survey module and thus has not been preregistered.

Switzerland should limit imports of foreign products to protect the national economy.

Addressing climate change requires more state intervention; addressing climate change requires less state intervention; state intervention does not affect the climate.

Author Biography

Manfred Elsig is a Professor of International Relations and Director of Research at the World Trade Institute, University of Bern. He is the co-founder of the Design of Trade Agreements Database.

Gabriele Spilker is a Professor of “International Politics—Global Inequality” at the Department of Politics and Public Administration at the University of Konstanz and co-speaker of the Excellence Cluster “The Politics of Inequality.”

Notes

The data underlying this article are available on the ISQ Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/isq.