-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jon C W Pevehouse, Felicity Vabulas, Nudging the Needle: Foreign Lobbies and US Human Rights Ratings, International Studies Quarterly, Volume 63, Issue 1, March 2019, Pages 85–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqy052

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Newspapers print alarming headlines when foreign governments hire U.S.-based lobbyists to promote their interests in Washington D.C. But does foreign lobbying systematically affect U.S. foreign policy? We provide an analysis of the influence of foreign lobbying on one important component of U.S. foreign policy: the evaluation of human rights practices abroad. U.S. human rights ratings can have a large impact on American foreign policy. They affect foreign aid, sanctions, and trade. Thus, we expect that many countries seek to tilt State Department Country Reports on Human Rights in their favor through information they provide to U.S.-based lobbyists. Our statistical analysis of these State Department reports and lobbying data from the Foreign Agent Registration Act between 1976‒2012 shows that, holding other factors equal, more foreign lobbying leads to more favorable U.S. human rights reports—when compared to both previous reports and Amnesty International reports. Furthermore, our findings contribute to the growing literature on performance indicators like human rights ratings by highlighting the politics of how those ratings are generated.

For many years, observers have worried about the role of foreign governments in shaping US foreign policy (Bogardus 2011; Narayanswamy, LaFleur, and Rosiak 2009; Newhouse 2009; Stern 2011). During World War II, American officials feared that Nazi Germany was paying public relations firms to propagandize American journalists. Half a century later, the 1996 Clinton campaign faced widespread criticism after reporters uncovered that the Chinese government had directed donations to the Democratic National Committee (DNC) (Miller 1996; Woodward and Duffy 1997).

Recent scandals in Washington, DC, reflect such concerns about the connections between foreign lobbying and US foreign policy. Former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn received more than |${\$}$|500,000 during the fall of 2016 to help the Turkish government discredit an exiled cleric living in the United States (Wilkie and Blumenthal 2017); between 2012 and 2014, President Donald Trump's former campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, lobbied for a Brussels-based think tank that supported Ukraine's Russia-linked Party of Regions (Arnsdorf 2017); and one of Trump's newest appointees to the Commission on White House Fellowships, Richard Holt, was paid |${\$}$|430,000 by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in exchange for “advice on legislative and public affairs strategies” (Kreig 2017).

But does the influence of foreign lobbying on US foreign policy go beyond this handful of stories? Previous academic research provides some evidence that foreign lobbying can have a significant effect on US foreign policy. For example, recent studies demonstrate that foreign countries can influence both the amount and terms of their foreign aid by lobbying the US government (Licht 2010; Montes-Rojas 2013). Furthermore, scholars also show that foreign lobbying affects important trade relationships: It can not only help foreign governments obtain favorable quotas (Berman and Heineman 1963) but can also influence the effective tariff rates levied on industrial products and textiles (Gawande, Krishna, and Robbins 2006; Grossman and Helpman 1992; Hafner-Burton 2013; Kee, Olarreaga, and Silva 2007).

We contribute to this research by looking at the effect of foreign lobbying on a different dimension of US foreign policy: US ratings of human rights abroad. The State Department makes no secret about the importance of its human rights reports: “We use the reports to shape American foreign policy, including our determination and allocation of foreign aid and security sector assistance” (State Department 2015). Unfavorable reports can mean the difference between receiving and not receiving millions of dollars of aid, (Cingranelli and Pasquarello 1985, 560; Demirel-Pegg and Moskowitz 2009; Lebovic and Voeten 2009); can play a role in the imposition of sanctions (Kritz 1996; Stirling 1996); and may strongly affect the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) to a country (Richards, Gelleny and Sacko 2001; Blanton and Blanton 2007; Barry, Clay, and Flynn 2013). Given the stakes, it should not surprise anyone that many foreign governments go to great lengths to ensure favorable reports.

We examine one of the ways that foreign governments try to affect the naming and shaming campaigns towards them—by hiring lobbyists to frame information to nudge reports in a more favorable direction. We use an original compilation of data from the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA)—which requires foreign governments to disclose lobbying activities to the Department of Justice—to show that many foreign governments routinely hire US-based lobbyists to provide information to influence how the legislative and executive branch view, and report on, their human rights practices. Indeed, both journalists and academics have referred to this group as “the torturers lobby” (Brogan 1992). We also provide evidence that this foreign lobbying influences human rights reports: according to our estimates, increases in lobbying efforts by a foreign government increase the probability of a more favorable human rights report by as much as 25 percent.

We evaluate the potential effect of foreign lobbying on human rights reports in two ways. First, we compare the annual State Department Country Reports on Human Rights to Amnesty International's (Amnesty) human rights reports from 1976 to 2012. Second, we look for changes over time in the annual State Department Country Reports that foreign lobbying might explain. In other words, we demonstrate that foreign governments can influence the change in State Department reports from one year to the next. In both cases, we show that the bias in reports persists even after accounting for a number of factors that could confound the relationship between human rights reports and lobbying.

We are not the first to argue that US human rights reporting may be biased (Innes 1992; Cohen 1996; Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001; Goodman and Jinks 2003; Qian and Yanagizawa-Drott 2009; Clark and Sikkink 2013; Hafner-Burton and Ron 2013; Fariss 2014). However, previous scholarship focuses on the difficulty of measuring concepts like human rights or the role of strategic factors, such as trade and security relationships, in tilting these reports. We are, to our knowledge, the first to show that foreign governments can actively manipulate these reports through lobbying.

The Creation and Use of Human Rights Ratings

The State Department annually submits to Congress a set of Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for all United Nations member states.1 These reports originated during the Nixon administration when various members of Congress wanted to more tightly tie American foreign policy to human rights (Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001). The Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) of 1961 (sections 116(d) and 502B (b)) and section 504 of the Trade Act of 1974 specify that the Secretary of State shall submit to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate, "a full and complete report regarding the status of internationally recognized human rights, within the meaning of subsection (A) in countries that receive assistance under this part, and (B) in all other foreign countries which are members of the United Nations and which are not otherwise the subject of a human rights report under this Act." Together, these reports describe foreign governments’ adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, outlining their performance in civil, political, individual, and workers’ rights. Evidence within the reports includes the source, location, timing, and severity of abuses.

Amnesty International—a London-based nongovernme-ntal organization with members around the globe—also issues annual human rights reports to draw attention to human rights practices in nearly every country in the world.2 Their reports focus on similar rights and institutions to the State Department reports (Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001, 656). Amnesty's methodology for generating these reports is very similar to that used by the State Department, although they rely more on non-state sources. The sections in each report are tailored to the relevant evidence but may include such topics as enforced killings, violence against women, freedom of assembly, refugees’ and migrants’ rights, and torture.

Today, a widely used data set known as the Political Terror Scale (PTS) quantifies these two data sources into two numerical measures of a state's respect for the human rights of its citizens (Gibney and Dalton 1996; Wood and Gibney 2010).3 To construct the data, two senior coders score each report on a five-point index (0–5) for each country in each year and record them separately.4 Higher scores represent higher levels of repression. The State Department and Amnesty International human rights ratings are widely used in policy making,5 the field of human rights research (Cingranelli and Pasquarello 1985; Green 2001; Neumayer 2005; Vreeland 2008; Murdie and Davis 2012; Clark and Sikkink 2013; Fariss 2014) and increasingly in international relations more generally (Nanda, Scarritt, and Shepherd 1981).

Why should state leaders care about these reports? By publishing its human rights reports, the State Department seeks to use this tool of soft power to shape the preferences of myriad actors throughout the world. While there could be reputational consequences of being perceived as a human rights violator in the eyes of the American public (see, for example, Tomz and Weeks 2018), there are also direct policy implications that flow from the State Department reports. Existing scholarship suggests that the United States uses the reports as intended: to punish (or reward) states with poor (or laudable) human rights records. A poor report from the State Department can cost countries valuable aid dollars (Cingranelli and Pasquarello 1985; Lebovic and Voeten 2009).6 Moreover, research ties trade preferences to human rights records (Hafner-Burton 2005; 2013). Poor human rights reports can also detrimentally affect foreign direct investment (FDI) (Richards, Gelleny, and Sacko 2001; Blanton and Blanton 2007; Barry, Clay, and Flynn 2013) and bring sanctions (Kritz 1996; Stirling 1996). Thus, countries have a strong incentive for the State Department to report them as being respectful of human rights. Indeed, there is an increasing use of human rights reports to assess and influence policy abroad. In general, scholars argue that states increasingly use comparative performance indicators based on systematic monitoring to influence important policy outputs worldwide (Kelley and Simmons 2015).

While the State Department reports have been widely used since their first publication in the mid-1970s, they have also been controversial (Carleton and Stohl 1987; Innes 1992; Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001). During the mid-1990s, for example, the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights (1993),7 a US-based NGO, issued a 400 + page annual critique of the reports, mostly claiming that they were highly speculative and not uniform in style or content across countries.

Scholars also criticize the reports for maintaining biased ratings towards countries that are geo-strategically important for the United States. This systematic bias is shown through various statistical analyses that compare the US Country Reports to Amnesty International reports. These analyses reveal that Cold War era reports described human rights as more repressive in countries that were ideologically opposed to the United States and slanted more favorably in countries where the United States had strategic interests (Poe and Tate 1994; Qian and Yanagizawa-Drott 2009). Even beyond the Cold War era, Poe, Carey, and Vazquez (2001) show that the US reports favor US allies and trading partners while discriminating against rivals. Research also shows that the US reports are less harsh than Amnesty International in evaluating the human rights practices of other governments (Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001; Nieman and Ring 2015).8

Why Foreign Principals Hire Lobbyists to Affect Human Rights Reports

States are aware that their human rights record could influence US foreign policies including foreign aid allocation, trade policy, the imposition of sanctions, and FDI. We therefore argue that foreign governments hire lobbyists to promote their human rights policies with US legislators, executive branch officials, and the US public at large. A review of our foreign lobbying data (discussed below) reveals many attempts along these lines. For example, in the beginning of 2012, Algeria hired Foley Hoag, LLP to “contact US Government officials and congressional staffers to promote Algerian-US relations and respect for human rights” (FARA 2012, 3). Foley Hoag reported receiving over |${\$}$|200,000 for six months of work on this project. In another recent example, Morocco hired Vision Americas, LLC to “communicate with members of Congress and congressional staffs on issues related to US-Morocco relations including human rights developments in the region, Morocco's role in the Middle East Peace Process, and the Western Sahara issue” (FARA 2012, 154).

It is not just a recent trend for foreign governments to hire lobbyists to influence human rights perceptions. For example, in 1978, the government of Nicaragua hired MacKenzie McCheyne, Inc., for |${\$}$|281,500 to “counter the attacks on Nicaragua which appear in the press charging human rights violations and political corruption…. And to present a favorable image” (FARA 1978, 359). These examples demonstrate one part of our argument: While foreign governments can directly lobby the State Department, a key tool in nudging the needle of human rights reports is hiring outside lobbyists to influence a broader perception of human rights abuses in a country. The State Department's own description of the Country Report generation process allows for any of these possibilities:

The annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices are based on information available from a wide variety of sources, including US and foreign government officials; victims of human rights abuse; academic and congressional studies; and reports from the press, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) concerned with human rights.9

This underscores an important part of our argument: Many hands touch these State Department reports, and thus entry points for lobbyists are diffuse rather than through a single channel. The State Department human rights reports begin with data and write-ups supplied by embassy staff overseas. They then transmit this information to State Department officials at Foggy Bottom who process them by consulting US and foreign government officials and other sources.

There are many points of contact between Congress and State too as State edits the reports. For instance, members of Congress regularly send letters to the State Department—referred to as “Congressionals”—with the hopes of influencing these reports. Moreover, there is a lot of give and take between these offices in the final product as State routinely meets with staffers on the Hill: "The different bureaus continue to have tremendous controversies over how to characterize human rights situations in different countries, " said Roberta Cohen, a former deputy assistant secretary in the Carter administration's human rights bureau. "That indicates these reports matter and have influence” (McMahon 2009).

We lean on the rich American politics literature on the role of information in lobbying (for example, Wright 1990; Hansen and Mitchell 2000; Hall and Deardorff 2006), to build our theory. We argue that foreign governments try to influence State Department reports by hiring US-based lobbyists who provide information to the parties that shape these reports. American politics scholars (Austen-Smith 1993; Austen-Smith and Wright 1994, 1995; Bauer, Pool, and Dexter 1963; Wright 1990; Hansen 1991,Milbrath 1960; Hall and Deardorff 2006) emphasize that information from lobbyists is influential because members of Congress face powerful time constraints. Lobbyists can affect policy, then, by helping to conduct the background work or provide congressional committees information to sponsor or draft time-consuming bills.

In the case of lobbying to affect human rights reports, two kinds of information are present: direct and indirect. First, lobbyists could provide direct informational input. In this scenario, foreign nationals hire US-based lobbyists to relay information about human rights practices or reforms abroad to State Department officials and congressional staffers. For example, in 1985, Haiti hired Garrett & Company at a cost of |${\$}$|65,000 for a six-month period to “meet with members of Congress to discuss Haiti's need for foreign aid and its compliance with US human rights policy”(FARA 1985, 246). Furthermore, lobbyists arrange travel to countries so that members of Congress and staffers may witness “facts on the ground” related to human rights practices. As noted by one Washington-based journalist, foreign travel remains a significant loophole for lobbyists to attempt to influence Congress (Goldmacher 2014).

This information from foreign lobbyists might alter the political context in which US policy makers make choices. Indeed, there is a particular need for information from overseas-based actors because the public is relatively uninformed about foreign affairs (Goldsen and Almond 1950; Jacobs and Page 2005), but so are many members of Congress (Kull and Ramsay 2000). For example, Milner (1997) shows that the role of endorsers providing information is key for legislative movement on international issues (see also Wright 1990; Austen-Smith and Wright 1994; Hojnacki and Kimball 1998). Lobbyists can highlight nuanced circumstances like civil conflict, natural disasters, or health care epidemics that require situational and contextual information. This could affect perceptions of the foreign country and therefore the American evaluation of human rights.

We argue that this information is particularly useful to congressional staffers who work in a low-incentive and low-knowledge environment concerning human rights abroad. First, unless a detailed accounting of human rights abroad favors their district, they are unlikely to learn about human rights on their own, instead erring on the side of accepting information from US-based lobbyists or other sources. Moreover, as Cutrone and Fordham (2010) point out, members of Congress may also overlook the egregious human rights actions of countries with which their constituents have harmonious economic relations. This highlights several roles for lobbyists: to provide information where it is not otherwise high priority and to underscore the economic congruence of the country in question.

Second, consolidated information about human rights abroad may be useful to staffers because of the highly decentralized network of human rights-related civil society actors abroad. Amidst what might otherwise be perceived as lots of noise, Congress may rely on lobbyists for cohesive information that still displays nuanced local information.

The historically Western orientation of human rights evaluations may also contribute to a low-knowledge environment. National governments sometimes resist adhering to international norms they perceive as contradicting local cultural or social values—and countries may feel that these divergences require culturally sensitive explanations to push members of Congress (or congressional staffers) to better understand the subtleties. These challenges present foreign lobbyists with a unique possibility to frame information for US government officials. Scholars of American politics (for example, McGrath 2007, 269), argue that framing is an important tool of lobbyists. Besides the cultural context, lobbyists and their clients attempt to provide political context around reported human rights issues. For example, representatives of a state can argue that a government's behavior may not be perfect, but difficult local conditions (for example, terrorist threats, low state capacity, and rogue security officials) help explain what might appear to be human rights abuses. This framing may go a long way in nudging the needle in human rights reports.

One question that arises is why foreign principals rely on US lobbyists to make these connections rather than leaning on their own official diplomatic corps? On the one hand, American embassies are in regular communication with government officials of host states. On the other hand, State Department officials tend to formally meet with foreign officials only under specific conditions, and it can be less sensitive to work through a third party on issues such as human rights. While human rights may get attention from senior State officials on special global platforms (like the United Nations General Assembly, for example), it is often also necessary or more efficient to conduct discussions at lower levels where schedules are less demanding and conversations do not risk the pressure of a global audience. Lobbyists can help foreign governments achieve particular objectives or press their cases in ways that an embassy official or ambassador might shy away from. Moreover, unfiltered, undiplomatic communication can be particularly valuable when Americans (lobbyists) talk to other Americans (government officials).

In addition, lobbyists who have served in either State or on a congressional staff may have information regarding who the key players are in generating these human rights reports. This gives them access to the “right” people (Hansen 1991). The 2015 allegations concerning the Clinton Foundation's acceptance of contributions from foreign entities indeed centers on lobbyists facilitating meetings between official diplomats and influential bureaucrats. In that case, Algeria raised both its donations to the Foundation and its hiring of foreign lobbyists once the Obama administration announced Hillary Clinton as the incoming secretary of state (Helderman and Hamburger 2015). Our own lobbying data show Algeria's lobbying increasing at that time. There were self-reported meetings between members of the Algerian delegation to the United States and both the Algerian desk officer and a human rights officer at State—all facilitated by an American lobbying firm. Last, there is evidence that human rights reports can be “sticky;” that is, they may be slow to change after past periods of severe abuse (Clark and Sikkink 2013). Foreign lobbyists may be particularly advantageous in supplying direct information to help break a state out of a historical pattern. Instead of allowing reporters to assume path dependence, lobbyists can highlight recent institutional changes in the foreign country.

The second kind of information that lobbyists may supply to State Department officials and Congressional staffers may be indirect. Foreign governments may hire lobbyists as part of an extensive public relations scheme to improve the overall impression of the country in the United States. Lobbyists might not directly target their efforts at human rights reports, per se, but instead may center their efforts on broad-scale image polishing of the country. In these instances, lobbyists have wide-ranging goals that might spill over to nudge the needle on human rights reports. For example, when asked to explain Saudi Arabia's recent all-encompassing foreign lobbying efforts, a government watchdog group said that “having an array of people representing the country in Washington helps Saudi Arabia keep the focus on what a great ally it is in the Middle East, not on issues like what women are and aren't allowed to do there” (Ho 2016). This kind of foreign lobbying might be less direct but no less important.

This phenomenon of indirect information is not exclusive to Saudi Arabia. Many records in the FARA data suggest that governments hire PR firms for millions of dollars to conduct large-scale PR campaigns. Here, rather than focusing framing efforts on individual members of Congress or State Department officials, firms and their clients try to reach the general public in hopes of creating positive images of their state and government. Studies show that international public relations campaigns can change the prominence and valence of that country's media coverage and public opinion in the United States (Zhang and Cameron 2003; Lee 2007). Positive views from these transnational PR campaigns could provide a positive context that might shape State Department reports. These predictions again align with studies on domestic lobbying where lobbyists attempt to focus attention on issues, facts, and appeals that will lead to acceptance of their client's point of view. The 2014 lobbying by Nigeria in the context of the Boko Haram kidnappings is an example of these dynamics. After Boko Haram's kidnapping of 200 schoolgirls, Nigeria and the Goodluck Jonathan administration immediately hired the public relations firm Levick to help change the “international and local media narrative” for N195 million (|${\$}$|1.2 million).

This direct and indirect information-based story makes foreign lobbying stand out. In contrast, domestic-based lobbying may also play an electoral pressure role that foreign lobbying cannot play (Milner 1997). Federal regulations prohibit foreign principals from making campaign contributions in US elections, so foreign lobbying does not closely connect with voting.10 However, while the tools of lobbyists working for foreign nationals might differ from those pursuing domestic agendas, they share a similar goal of extracting resources for their clients.

An important mechanism in our theory concerns bias: Why would executive or legislative branch officials or staffers believe lobbyists’ direct or indirect information regarding human rights and let it subsequently influence their input into Country Reports, knowing it might be from a biased source? To be sure, one might suppose that the foreign principal's act of hiring a lobbyist may inadvertently signal its human rights “type”: There may be no reason to hire a lobbyist unless there is potential ambiguity in a state's human rights record. Yet, research on lobbying in American politics shows the predominance of “defensive” lobbying so that an interest group may simply lobby to “keep up with the Joneses”. This means that lobbying does not signal a “bad type” (Austen-Smith and Wright 1994; Richter, Samphantharak and Timmons 2009) and that US government officials do not just dismiss the information outright.

Research also shows that continued exposure to information, even when there is knowledge that it might be biased, can lead to updated beliefs (Bullock 2009). We argue this is especially true against a counterfactual of no lobbying. For example, US government officials will surely perceive a Moroccan lobbyist as taking the party line and casting the best light possible on human rights in Morocco. While that might only change beliefs of a recipient at the margins, it would certainly change their beliefs more than for a country that does not lobby at all. Moreover, the science of implicit cognition suggests that even when staffers try to sift out bad information, they may not realize how or when a lobbyist's information may be influencing their reports. This research shows that actors do not always have conscious, intentional control over their processes of social perception, impression formation, and judgment (Greenwald and Krieger 2006, 946).

Whether the mechanism is direct or indirect exposure to information (or both), the end result is that State Department reports are likely to be less harsh in the presence of lobbying than in cases where no lobbying takes place. Indeed, previous research shows that almost all the bias in all sources of human rights reporting is underreporting of violations (Hill, Moore, and Mukherjee 2013; Conrad, Haglund, and Moore 2014). We contend that foreign lobbying of US government officials will tend to exacerbate this “biased undercount” of abuse on US State Department reports.

In sum, foreign governments hire US-based lobbyists to supply both direct and indirect information to a wide range of actors that influence US State Department human rights reports. These actors range from members of Congress and their staff to State Department officials—as well as to the wider public through general PR campaigns. That foreign governments lobby on human rights is strong evidence that there is at least a perceived upside of having more favorable human rights reports from the State Department.

Quantitative Analysis

In order to move beyond anecdotal evidence regarding the connection between foreign lobbying and human rights reports, we quantitatively evaluate the effects of these lobbying activities. To do so, we turn to the data from the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA). Since 1938, FARA has governed the behavior of foreign actors lobbying US officials. FARA requires that any domestic lobbying firm (referred to as the “foreign agent”) hired by a foreign actor such as a government, corporation, industry group, or individual (referred to as the “foreign principal”) register with the Department of Justice (DOJ). The lobbyists must also disclose the purpose for which they were hired, and how they spent money documented in the lobbying contract. The DOJ is then required to disclose these amounts in an annual report to Congress (since the mid-1990s in semi-annual reports). This holistic data source provides a unique opportunity to understand the bigger picture of foreign lobbying rather than focusing on one-off cases (Baumgartner and Leech 1998).

Our research team coded the semi-annual FARA reports back to 1942.11 For each report, we classified the foreign principal (for example, government, corporation, individual, etc.); the purpose for which they were hired; and where available, the dollar value of the lobbying contract. The records in FARA are very clear as to the identity of the foreign principal. In our analysis, we focus only on government lobbying efforts, since governments are incentivized to garner a more favorable human rights report.

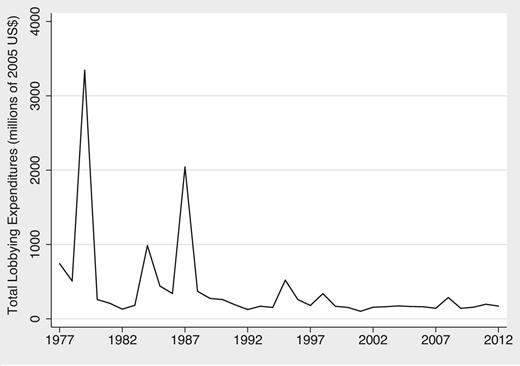

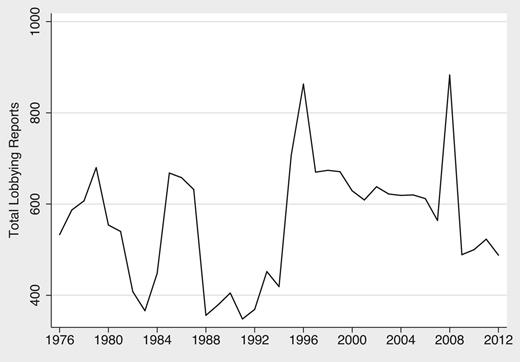

Figures 1 and 2 show foreign lobbying dollars (adjusted for inflation) and lobbying filings between 1976 and 2012.12 We note that despite a couple of larger years of lobbying expenditures, the overall level of foreign lobbying dollars spent has been relatively constant since 1976.13 The number of lobbying filings has increased since the end of the Cold War, but has tapered off in recent years. This means that while dollars spent remain even, foreign governments might be spreading their money across more contractors or through an increased array of projects.

Yearly Totals of Lobbying Expenditures Reported in FARA Documents

Yearly Totals of Lobbying Contracts Reported in FARA Documents

It is important to recognize that FARA has no jurisdiction over US-based ethnic lobby groups (for example, The American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the Cuban-American National Foundation (CANF), or the Armenian Assembly of America (AAA)). Many ethnic lobbies form domestic-based PACs or similar institutions, and thus they remain outside the boundaries of FARA. We do not assess the influence of domestic lobby groups (that is, Diasporas or interest groups in the United States) who may advocate for their former state. By focusing on foreign lobbies only, however, we can hone in on the informational role of lobbying.

Related to this point is an important question: Who, exactly, is lobbying from abroad? While others address this question in a general matter (see Pevehouse and Vabulas 2015), below we analyze what factors are correlated with foreign governments hiring American lobbyists. A small literature exists analyzing this question, but our short answer is: nearly everyone. Of the 132 countries analyzed in our baseline model, only 9 did not hire any lobbying firms over the period of observation. As we discuss below, a variety of factors correlate both positively and negatively with the propensity of foreign governments to hire lobbying firms. Again, although it is beyond the scope of this paper to fully analyze which states lobby, we show that controlling for who lobbies does not influence our core results concerning lobbying and human rights.

We approach the question of measuring bias in two ways. The first is to use the Amnesty International country reports as a baseline. Our theory predicts that lobbying will cause the US evaluation of human rights conditions to diverge from those of trusted human rights NGOs. Our second approach is to model whether the State Department ratings change over time, using the Amnesty ratings as a control variable (although our results are robust to their exclusion as well). These latter estimates clearly indicate that lobbying influences the State Department reports irrespective of the judgments of Amnesty.

Why should we regard Amnesty International reports as a “baseline”? A recent study by Hill, Moore, and Mukherjee (2013, 12) underscores that Amnesty country reports are indeed reliable. It concludes that “[Amnesty International] largely maintains its credibility standard, responding infrequently to organizational incentives to exaggerate allegations.” Amnesty goes to great lengths to ensure that lobbyists do not influence them. This independent finding gives us confidence in using the Amnesty reports as a baseline for assessing bias in the State Department country reports.

Moreover, Amnesty not only has a strong incentive to issue credible and unbiased reports because it is interested in distinguishing the quality of its products from those of other human rights NGOs and state research services, but also because it is less reliant on potentially biased information from foreign governments. Nonetheless, we take into account research showing that geopolitical factors play a role in attracting Amnesty attention (Hendrix and Wong 2014). We therefore incorporate these geopolitical variables—including aid, alliance, and trade ties—in the set of control variables explained below.14

We initially operationalize our dependent variable, which we label StateHighit+1, as an indicator variable, coded 1 if the State Department Human Rights Report for state i in year t + 1 is coded more favorably than the equivalent report by Amnesty International in that year. We lead this variable to year t + 1 as a hedge against reverse causality.15 As indicated earlier, our measures come from the PTS data, which maintains the separate coding for State Department and Amnesty International Reports (descriptive statistics for all data are in appendix Table 8).

The second operationalization of our dependent variable, Stateit+1, is the State Department rating itself. Because our different dependent variables have different properties, we use two estimation methods. For our initial dependent variable, StateHigh, we use logistic regression with country fixed effects. For our other dependent variable, we use OLS regression with country fixed effects.16 We note that for the State Department and Amnesty ratings, higher values indicate worse human rights reports. Thus, for our independent variables of interest, we expect higher levels of lobbying to correlate with lower values of our second outcome measure.

To measure the influence of foreign lobbies, we alternate between two measures for our key independent variable. The first is the log of the total number of yearly lobbying records for each government, whether or not those records disclosed the amount of expenditures by each agent (Number of Lobbying Reports). The second measure is the log of the total value of all contracts signed by lobbyists representing the government as reported in FARA (Lobbying |${\$}$|). Again, for both of these measures we include only those records linked to government principals—excluding individuals not affiliated with the government, as well as corporations.

For control variables, we draw on existing quantitative studies of bias in State Department human rights reports as discussed above (Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001; Qian and Yanagizawa-Drott 2009; Nieman and Ring 2015). We also include other variables that we hypothesize may influence both the level of foreign lobbying and the State Department's potential political incentives to report human rights abuses.

First, we are concerned that a significant human rights violation could itself lead to more lobbying (as our anecdotes suggest) and lead to increasingly negative human rights ratings (potentially by both Amnesty and the State Department). Even holding constant other factors that could drive any divergence between the two reports, we do not want abuses themselves to give rise to a spurious correlation between lobbying and our outcome of interest. Thus, we include the value of the Amnesty rating of country i in year t (Amnesty) as a control in the model (Hendrix and Wong 2014).

Second, we control for the regime type of state i by including its Polity IV regime type score (Regime Type), which ranges from −10 to + 10 (Marshall and Jaggers 2002). Democracies typically promote better human rights (Poe and Tate 1994; Davenport 1999; Poe, Tate, and Keith 1999; Apodaca 2001). Moreover, as indicated above, one of the criticisms of human rights reporting practices is a bias towards those with alliances, aid, and trade links to the United States (Ron, Ramos, and Rodgers 2005; Hendrix and Wong 2014). Given that many of the states fitting that description for the United States are generally democracies, it is important to control for the independent influence of democracy.

Third, we include an indicator variable (Alliance) for whether state i is allied with the United States in year t.17 As our previous discussion indicated, critics of State Department reports argue that allies receive particularly mild treatments over time (Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001, 670). Furthermore, Hendrix and Wong (2014) show that countries with strong security alliances with the United States are disproportionately targeted in Amnesty's press releases and urgent action reports. Moreover, it is possible that allies will more frequently lobby the United States for policy changes (Paul and Paul 2009).

Fourth, we include a Cold War dummy variable (Cold War) coded as 1 during Cold War years to control for the fact that foreign lobbying for human rights reports might be structurally different during this time frame. Many of the critiques of the State Department reports note that pressures of the Cold War led to a bias against states allied with or sympathetic with the Soviet Union (Mitchell and McCormick 1988; Poe and Tate 1994). Thus, we might expect the underlying data-generating process to shift after the end of the Cold War.

Fifth, we include a measure of foreign assistance received by state i in year t. This variable (Foreign Aid) takes from the US Overseas Loans and Grants (Greenbook) data (2016) and includes all non-military foreign aid provided to the recipient. The presence of high levels of foreign aid would indicate that the recipient state is important to the United States and thus more likely to experience a positive bias in reporting from the State Department (Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001).

Sixth, we control for two economic factors that should measure respect for human rights and the underlying ability of states to lobby the US government (Hafner-Burton 2005; Neumayer 2005). We control for logged per capita GDP (pcGDP) because the wealth of a country might correlate with both lobbying and HR reports. We also control for logged GDP (GDP), measured for each state i in year t, because the size of the country might correlate with both lobbying and HR reports.18

Results

The estimates of our initial model are in Table 1, Column 1. Our independent variable of interest, Number of Lobbying Reports, is positive and statistically significant, indicating that an increase in lobbying reports by a government increases the probability of a more positive (than Amnesty) State Department report. Column 2 reports the equivalent estimate for Lobbying |${\$}$|, which is also positive and statistically significant. Thus, in the absence of any covariates, there is a clear correlation between lobbying and higher State Department human rights ratings.19

Determinants of Higher State Department Country Report Scores Compared to Amnesty International Country Report Scores

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||

| (2.05) | (3.37) | (2.98) | (3.14) | |||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| (2.29) | (2.45) | |||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.23 | ||

| (3.60) | (3.38) | (2.40) | (3.73) | |||

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| (2.92) | (2.87) | (2.38) | (2.82) | |||

| Regime type | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| (2.35) | (2.32) | (2.09) | (2.38) | |||

| GDP (log) | −2.40 | −2.31 | −3.02 | −2.43 | ||

| (−7.31) | (−6.98) | (−7.01) | (−7.33) | |||

| Per capita GDP (log) | 2.41 | 2.38 | 3.31 | 2.42 | ||

| (6.40) | (6.22) | (7.11) | (6.38) | |||

| Alliance with US | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.07 | ||

| (0.36) | (0.44) | (0.85) | (0.11) | |||

| Cold War | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.50 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.38) | (1.94) | (3.50) | |||

| Trade with US (log) | −0.10 | |||||

| (−2.08) | ||||||

| Diplomatic representation in US | 0.13 | |||||

| (1.62) | ||||||

| Observations | 4,418 | 4,279 | 3,503 | 3,429 | 2,878 | 3,476 |

| Number of countries | 158 | 158 | 133 | 132 | 131 | 133 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||

| (2.05) | (3.37) | (2.98) | (3.14) | |||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| (2.29) | (2.45) | |||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.23 | ||

| (3.60) | (3.38) | (2.40) | (3.73) | |||

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| (2.92) | (2.87) | (2.38) | (2.82) | |||

| Regime type | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| (2.35) | (2.32) | (2.09) | (2.38) | |||

| GDP (log) | −2.40 | −2.31 | −3.02 | −2.43 | ||

| (−7.31) | (−6.98) | (−7.01) | (−7.33) | |||

| Per capita GDP (log) | 2.41 | 2.38 | 3.31 | 2.42 | ||

| (6.40) | (6.22) | (7.11) | (6.38) | |||

| Alliance with US | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.07 | ||

| (0.36) | (0.44) | (0.85) | (0.11) | |||

| Cold War | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.50 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.38) | (1.94) | (3.50) | |||

| Trade with US (log) | −0.10 | |||||

| (−2.08) | ||||||

| Diplomatic representation in US | 0.13 | |||||

| (1.62) | ||||||

| Observations | 4,418 | 4,279 | 3,503 | 3,429 | 2,878 | 3,476 |

| Number of countries | 158 | 158 | 133 | 132 | 131 | 133 |

Note: z-statistics in parentheses. Each model estimated using logistic regression with country fixed-effects.

Determinants of Higher State Department Country Report Scores Compared to Amnesty International Country Report Scores

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||

| (2.05) | (3.37) | (2.98) | (3.14) | |||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| (2.29) | (2.45) | |||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.23 | ||

| (3.60) | (3.38) | (2.40) | (3.73) | |||

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| (2.92) | (2.87) | (2.38) | (2.82) | |||

| Regime type | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| (2.35) | (2.32) | (2.09) | (2.38) | |||

| GDP (log) | −2.40 | −2.31 | −3.02 | −2.43 | ||

| (−7.31) | (−6.98) | (−7.01) | (−7.33) | |||

| Per capita GDP (log) | 2.41 | 2.38 | 3.31 | 2.42 | ||

| (6.40) | (6.22) | (7.11) | (6.38) | |||

| Alliance with US | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.07 | ||

| (0.36) | (0.44) | (0.85) | (0.11) | |||

| Cold War | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.50 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.38) | (1.94) | (3.50) | |||

| Trade with US (log) | −0.10 | |||||

| (−2.08) | ||||||

| Diplomatic representation in US | 0.13 | |||||

| (1.62) | ||||||

| Observations | 4,418 | 4,279 | 3,503 | 3,429 | 2,878 | 3,476 |

| Number of countries | 158 | 158 | 133 | 132 | 131 | 133 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||

| (2.05) | (3.37) | (2.98) | (3.14) | |||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| (2.29) | (2.45) | |||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.23 | ||

| (3.60) | (3.38) | (2.40) | (3.73) | |||

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| (2.92) | (2.87) | (2.38) | (2.82) | |||

| Regime type | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| (2.35) | (2.32) | (2.09) | (2.38) | |||

| GDP (log) | −2.40 | −2.31 | −3.02 | −2.43 | ||

| (−7.31) | (−6.98) | (−7.01) | (−7.33) | |||

| Per capita GDP (log) | 2.41 | 2.38 | 3.31 | 2.42 | ||

| (6.40) | (6.22) | (7.11) | (6.38) | |||

| Alliance with US | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.07 | ||

| (0.36) | (0.44) | (0.85) | (0.11) | |||

| Cold War | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.50 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.38) | (1.94) | (3.50) | |||

| Trade with US (log) | −0.10 | |||||

| (−2.08) | ||||||

| Diplomatic representation in US | 0.13 | |||||

| (1.62) | ||||||

| Observations | 4,418 | 4,279 | 3,503 | 3,429 | 2,878 | 3,476 |

| Number of countries | 158 | 158 | 133 | 132 | 131 | 133 |

Note: z-statistics in parentheses. Each model estimated using logistic regression with country fixed-effects.

Columns 3 and 4 of Table 1 add the rest of our independent variables. Our two theoretical variables of interests remain positive and statistically significant. The effect of lobbying is substantively significant as well—an increase of one standard deviation of the number of lobbying contracts yields a predicted increase of almost 25 percent in the probability of the State report being more favorable than the Amnesty report. The impact of the estimate of lobbying expenditures is significant as well—with predicted changes in predicted probabilities approximately 15 percent for a one standard-deviation increase in expenditures.

Most of the control variables take on the predicted sign too: More democratic and wealthier (on a per capita basis) states, and those receiving more US aid are more likely to receive more favorable ratings. The Cold War strongly influences ratings as suggested by previous studies (see Qian and Yanagizawa-Drott 2009). The same is true of economically larger countries who are less likely to receive a more favorable treatment. Finally, the presence of a formal military alliance seems to have little influence on our outcome of interest.20

To assess further the robustness of these results, we re-estimate the model from Column 1, but add two additional controls in turn. First, we include a measure of (logged) trade flows between the United States and the recipient country to measure their economic importance, but also to control for the demand for additional lobbying that might relate to trade policy.21 On the first issue, past work finds that trade leads to a bias of State Department reports (Poe, Carey, and Vazquez 2001) and Amnesty “Urgent Action” reports (Hendrix and Wong 2014). On the second issue, it is widely recognized that lobbying is an important determinant of trade policy (see among others Gawande, Krishna, and Olarreaga 2012). As shown in column 5, this new variable, Trade with US, achieves statistical significance, but the addition of this variable does not attenuate the effects of Number of Lobbying Reports.22

Column 6 adds a different covariate, Diplomatic Representation, which measures the level of diplomatic representation between the United States and other countries (Bayer 2006). Mistry (2013) argues that foreign lobbying may actually be a substitute for a weak ambassador in the foreign country or weak embassy and/or consular presence in the United States. When ambassadors and embassy staff are not accomplishing what foreign nationals’ desire in US foreign policy (or when their strategies need further bolstering), they may instead create information networks with US politicians and agencies through lobbyists. We find that the estimate of this variable is not statistically significant. Yet, we note that our main finding for Number of Lobbying Reports remains positive and statistically significant. Clearly, diplomacy and lobbying are both at play in shaping these reports.23

Our next set of models, shown in Table 2, utilizes our other dependent variable, NetStateit+1. This variable measures whether the State Department rating improves (or worsens) for a country in a given year. Much like our previous estimates, these models show consistent correlations between lobbying and more favorable State Department reports. Both of our key independent variables of are of the correct sign (more lobbying leads to better—that is, lower—ratings) and are statistically significant. In these final models, with the exception of Alliance, all of the variables are of the predicted sign and all are statistically significant.

| . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . | (10) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| (−2.57) | (−2.56) | (−1.99) | ||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | −0.005 | |||

| (−3.19) | ||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| (30.42) | (30.05) | (26.90) | (29.35) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (−2.94) | (−3.27) | (−1.56) | (−2.49) | |

| Regime type | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| (−8.29) | (−7.98) | (−7.75) | (−8.13) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.83 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| (11.90) | (11.38) | (10.55) | (12.34) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −1.00 | −0.98 | −1.21 | −1.04 |

| (−12.49) | (−11.92) | (−12.01) | (−12.88) | |

| Alliance with US | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.38 |

| (2.63) | (2.99) | (1.35) | (3.05) | |

| Cold War | −0.23 | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.23 |

| (−6.96) | (−6.70) | (−4.86) | (−6.99) | |

| Trade with US (log) | 0.01 | |||

| (1.47) | ||||

| Diplomatic representation in USA | −0.09 | |||

| (−4.86) | ||||

| Constant | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.12 |

| (3.20) | (3.36) | (1.88) | (3.81) | |

| Observations | 3,788 | 3,718 | 3,136 | 3,747 |

| R-squared | 0.306 | 0.298 | 0.305 | 0.304 |

| Number of countries | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 |

| . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . | (10) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| (−2.57) | (−2.56) | (−1.99) | ||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | −0.005 | |||

| (−3.19) | ||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| (30.42) | (30.05) | (26.90) | (29.35) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (−2.94) | (−3.27) | (−1.56) | (−2.49) | |

| Regime type | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| (−8.29) | (−7.98) | (−7.75) | (−8.13) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.83 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| (11.90) | (11.38) | (10.55) | (12.34) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −1.00 | −0.98 | −1.21 | −1.04 |

| (−12.49) | (−11.92) | (−12.01) | (−12.88) | |

| Alliance with US | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.38 |

| (2.63) | (2.99) | (1.35) | (3.05) | |

| Cold War | −0.23 | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.23 |

| (−6.96) | (−6.70) | (−4.86) | (−6.99) | |

| Trade with US (log) | 0.01 | |||

| (1.47) | ||||

| Diplomatic representation in USA | −0.09 | |||

| (−4.86) | ||||

| Constant | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.12 |

| (3.20) | (3.36) | (1.88) | (3.81) | |

| Observations | 3,788 | 3,718 | 3,136 | 3,747 |

| R-squared | 0.306 | 0.298 | 0.305 | 0.304 |

| Number of countries | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 |

Note: z-statistics in parentheses. Each model estimated using logistic regression with country fixed-effects.

| . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . | (10) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| (−2.57) | (−2.56) | (−1.99) | ||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | −0.005 | |||

| (−3.19) | ||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| (30.42) | (30.05) | (26.90) | (29.35) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (−2.94) | (−3.27) | (−1.56) | (−2.49) | |

| Regime type | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| (−8.29) | (−7.98) | (−7.75) | (−8.13) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.83 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| (11.90) | (11.38) | (10.55) | (12.34) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −1.00 | −0.98 | −1.21 | −1.04 |

| (−12.49) | (−11.92) | (−12.01) | (−12.88) | |

| Alliance with US | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.38 |

| (2.63) | (2.99) | (1.35) | (3.05) | |

| Cold War | −0.23 | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.23 |

| (−6.96) | (−6.70) | (−4.86) | (−6.99) | |

| Trade with US (log) | 0.01 | |||

| (1.47) | ||||

| Diplomatic representation in USA | −0.09 | |||

| (−4.86) | ||||

| Constant | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.12 |

| (3.20) | (3.36) | (1.88) | (3.81) | |

| Observations | 3,788 | 3,718 | 3,136 | 3,747 |

| R-squared | 0.306 | 0.298 | 0.305 | 0.304 |

| Number of countries | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 |

| . | (7) . | (8) . | (9) . | (10) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| (−2.57) | (−2.56) | (−1.99) | ||

| Lobbying |${\$}$| (log) | −0.005 | |||

| (−3.19) | ||||

| Amnesty rating | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| (30.42) | (30.05) | (26.90) | (29.35) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (−2.94) | (−3.27) | (−1.56) | (−2.49) | |

| Regime type | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| (−8.29) | (−7.98) | (−7.75) | (−8.13) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.83 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| (11.90) | (11.38) | (10.55) | (12.34) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −1.00 | −0.98 | −1.21 | −1.04 |

| (−12.49) | (−11.92) | (−12.01) | (−12.88) | |

| Alliance with US | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.38 |

| (2.63) | (2.99) | (1.35) | (3.05) | |

| Cold War | −0.23 | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.23 |

| (−6.96) | (−6.70) | (−4.86) | (−6.99) | |

| Trade with US (log) | 0.01 | |||

| (1.47) | ||||

| Diplomatic representation in USA | −0.09 | |||

| (−4.86) | ||||

| Constant | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.12 |

| (3.20) | (3.36) | (1.88) | (3.81) | |

| Observations | 3,788 | 3,718 | 3,136 | 3,747 |

| R-squared | 0.306 | 0.298 | 0.305 | 0.304 |

| Number of countries | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 |

Note: z-statistics in parentheses. Each model estimated using logistic regression with country fixed-effects.

We regard these findings as particularly important given that they do not rely on a comparison between the Amnesty reports and State reports. Rather, these models show that an increase in foreign lobbying appears to correlate with an improvement over time in State Department reports. As with our previous models, the substantive effects are noteworthy, but more modest in these models. A one standard deviation increase in the number of lobbying contracts yields a predicted shift of around 5 percent in the ratings measure, with a similar increase in lobbying expenditures yielding a similar prediction.

Our appendix contains a number of additional robustness checks, including substituting a measure of military aid for economic aid. We also, following Nieman and Ring (2015), eliminate all observations prior to 1980 because not all countries received annual reports before this year. We also estimate a series of models using Fariss's (2014) data on the status of human rights to control for actual violations of human rights (we replace our Amnesty score with this new measure). Using Fariss's latent variable data accounts for temporal trends in the human rights reports and lobbying behavior. Moreover, using the Fariss data as a control allows us to use a fuller set of observations since there are fewer Amnesty reports than State Department reports over our period of observation. Next, we control for the post-1993 period, when it appears there is more of a convergence of the reports. We also control for the 1992–1994 period where our data collection differed from the rest of the period of observation (see our data appendix for more description). Finally, we add, as an additional control, a measure of media coverage of human rights taken from Hendrix and Wong (2014).24 Since media attention could possibly drive differences between Amnesty and State Department reports, it may relate to lobbying attempts, too. As we discuss in the appendix, none of these substitutions or additions have any significant bearings on our previous findings.

Who Lobbies?

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to analyze fully the question of who chooses to lobby in the United States, as a robustness check, we re-analyze our initial model while controlling for a state's propensity to lobby. This helps us ensure that the process of deciding whether to lobby does not correlate with the probability that lobbying influences human rights reports. We do so by returning to our initial dependent variable (StateHighit+1), but use a bivariate probit model with unit fixed-effects to simultaneously estimate the probability that the country under observation hired a lobbyist in year t + 1 (we label this variable HireLobbyit+1). The bivariate probit model allows for correlated disturbances between these two equations.

Although the bivariate probit model does not have strong requirements for causal identification, we estimate two variants of the model out of an abundance of caution.25 Our first estimates, found in columns 11 and 12 of Table 3, include Cold War and Number of Lobbying Reports in our StateHighit+1 equation, but not in the HireLobbyit+1 equation. The HireLobbyit+1 model, on the other hand, includes two unique variables: our measure of Strategic Distance26 and a measure of the number of lobbyists hired by state i's enduring rival (labeled Rival Government Lobbies).27 We include the former, since it is likely that states who perceive they are less important to the United States should have a stronger incentive to lobby, yet our earlier statistical tests showed this variable is not correlated with the State Department ratings. We include the latter since our past work shows this variable to correlate with the choice to lobby and we have no reason to believe this variable will influence the State Department ratings for a country.

Bivariate Probit Estimates of Higher State Department Country Reports and Lobbyist Hiring

| . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (11) . | (12) . | (13) . | (14) . |

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.31) | |||

| Rival government lobbies | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| (1.94) | (1.25) | |||

| Amnesty rating | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| (0.42) | (2.68) | (1.23) | (3.85) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.59 | −1.80 | 0.77 | −1.33 |

| (1.81) | (−5.63) | (4.41) | (−6.73) | |

| Alliance with US | −0.15 | 1.10 | −1.05 | 0.25 |

| (−0.20) | (1.56) | (−2.02) | (0.65) | |

| Regime type | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| (−2.90) | (2.53) | (−3.21) | (2.27) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −0.28 | 1.99 | −0.73 | 1.34 |

| (−0.72) | (5.62) | (−3.43) | (5.93) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| (−1.25) | (1.84) | (−2.00) | (2.63) | |

| Strategic distance | 0.0001 | |||

| (4.34) | ||||

| Cold War | 0.19 | 0.37 | ||

| (1.77) | (4.10) | |||

| Constant | 1.81 | 0.98 | 4.70 | 2.38 |

| (0.00) | (0.56) | (0.00) | (2.00) | |

| (rho) | −0.123 | −0.055 | ||

| (−1.77) | (−0.986) | |||

| Observations | 2,405 | 2,405 | 3,303 | 3,303 |

| . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (11) . | (12) . | (13) . | (14) . |

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.31) | |||

| Rival government lobbies | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| (1.94) | (1.25) | |||

| Amnesty rating | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| (0.42) | (2.68) | (1.23) | (3.85) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.59 | −1.80 | 0.77 | −1.33 |

| (1.81) | (−5.63) | (4.41) | (−6.73) | |

| Alliance with US | −0.15 | 1.10 | −1.05 | 0.25 |

| (−0.20) | (1.56) | (−2.02) | (0.65) | |

| Regime type | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| (−2.90) | (2.53) | (−3.21) | (2.27) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −0.28 | 1.99 | −0.73 | 1.34 |

| (−0.72) | (5.62) | (−3.43) | (5.93) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| (−1.25) | (1.84) | (−2.00) | (2.63) | |

| Strategic distance | 0.0001 | |||

| (4.34) | ||||

| Cold War | 0.19 | 0.37 | ||

| (1.77) | (4.10) | |||

| Constant | 1.81 | 0.98 | 4.70 | 2.38 |

| (0.00) | (0.56) | (0.00) | (2.00) | |

| (rho) | −0.123 | −0.055 | ||

| (−1.77) | (−0.986) | |||

| Observations | 2,405 | 2,405 | 3,303 | 3,303 |

Note: z-statistics in parentheses. Each model estimated using bivariate probit with country fixed-effects.

Bivariate Probit Estimates of Higher State Department Country Reports and Lobbyist Hiring

| . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (11) . | (12) . | (13) . | (14) . |

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.31) | |||

| Rival government lobbies | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| (1.94) | (1.25) | |||

| Amnesty rating | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| (0.42) | (2.68) | (1.23) | (3.85) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.59 | −1.80 | 0.77 | −1.33 |

| (1.81) | (−5.63) | (4.41) | (−6.73) | |

| Alliance with US | −0.15 | 1.10 | −1.05 | 0.25 |

| (−0.20) | (1.56) | (−2.02) | (0.65) | |

| Regime type | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| (−2.90) | (2.53) | (−3.21) | (2.27) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −0.28 | 1.99 | −0.73 | 1.34 |

| (−0.72) | (5.62) | (−3.43) | (5.93) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| (−1.25) | (1.84) | (−2.00) | (2.63) | |

| Strategic distance | 0.0001 | |||

| (4.34) | ||||

| Cold War | 0.19 | 0.37 | ||

| (1.77) | (4.10) | |||

| Constant | 1.81 | 0.98 | 4.70 | 2.38 |

| (0.00) | (0.56) | (0.00) | (2.00) | |

| (rho) | −0.123 | −0.055 | ||

| (−1.77) | (−0.986) | |||

| Observations | 2,405 | 2,405 | 3,303 | 3,303 |

| . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . | HireLobbyit+1 . | StateHighit+1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | (11) . | (12) . | (13) . | (14) . |

| Number of lobbying reports (log) | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||

| (3.50) | (3.31) | |||

| Rival government lobbies | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| (1.94) | (1.25) | |||

| Amnesty rating | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| (0.42) | (2.68) | (1.23) | (3.85) | |

| GDP (log) | 0.59 | −1.80 | 0.77 | −1.33 |

| (1.81) | (−5.63) | (4.41) | (−6.73) | |

| Alliance with US | −0.15 | 1.10 | −1.05 | 0.25 |

| (−0.20) | (1.56) | (−2.02) | (0.65) | |

| Regime type | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| (−2.90) | (2.53) | (−3.21) | (2.27) | |

| Per capita GDP (log) | −0.28 | 1.99 | −0.73 | 1.34 |

| (−0.72) | (5.62) | (−3.43) | (5.93) | |

| Bilateral US economic aid (log) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| (−1.25) | (1.84) | (−2.00) | (2.63) | |

| Strategic distance | 0.0001 | |||

| (4.34) | ||||

| Cold War | 0.19 | 0.37 | ||

| (1.77) | (4.10) | |||

| Constant | 1.81 | 0.98 | 4.70 | 2.38 |

| (0.00) | (0.56) | (0.00) | (2.00) | |

| (rho) | −0.123 | −0.055 | ||

| (−1.77) | (−0.986) | |||

| Observations | 2,405 | 2,405 | 3,303 | 3,303 |

Note: z-statistics in parentheses. Each model estimated using bivariate probit with country fixed-effects.

The results are in Table 3. Column 11 shows the estimates of the correlates of hiring a lobbyist. As in our previous investigations, the more lobbyists working for a rival state, the greater propensity for a government to hire their own lobbyists. States with higher values of Strategic Distance are more likely to hire lobbyists, as are wealthier states (the estimate of GDP is positive and statistically significant). Conversely, states that are more democratic are less likely to employ lobbyists. Importantly, we note that the estimate of Amnesty is not statistically significant, suggesting no correlation between a state's human rights performance and the hiring of lobbyists the following year. Column 12 estimates a model identical to our initial baseline model, but controls for the correlation between the process of hiring a lobby and the State Department rating. These results are identical to the estimates presented in Table 1.

Columns 13 and 14 of Table 3 show the model re-estimated but without the Strategic Distance variable, since this variable is missing for about a third of our sample. As in our previous estimates, GDP is correlated with the hiring of lobbyists, while Rival Government Lobbies falls below traditional levels of statistical significance. In addition, GDP and Regime Type remain statistically significant, while Alliance, per capita GDP, and Economic Aid are each negatively correlated with hiring lobbyists. Also note in these results, the measure of human rights practice, as captured by the Amnesty variable, is not statistically significant. Finally, we also note that in neither of these models is the correlation between the error terms (rho) statistically significant, suggesting that we can model the processes as independent of one another. In sum, these bivariate probit models suggest that, even when controlling for who hires lobbyists, a strong correlation still exists between hiring those lobbyists and changing the nature of human rights reports over time.

Case Example: Chad

To illustrate the correlations in our large-N analysis, we examine efforts by the Republic of Chad to influence the perception of their human rights record in 1995 through lobbying. We examine Chad because it contains significant variation over time on our dependent variables and our key independent variable of interest. Chad hired Hayward International to perform “public relations” for |${\$}$|95,976.13 (FARA 1995, 125). According to the 1995 FARA report, “The registrant assisted the foreign principal with its visit to the 50th anniversary of the United Nations during the period of October 21 to October 29, 1995. The registrant liaised with United Nations professionals, arranged transportation for the President's entourage, set up meetings with business leaders, humanitarian and human rights organizations, the press and government officials.”

The lobbying firm's reported actions were indirect, that is, they were part of a larger public relations campaign rather than singularly focused towards human rights promotion. As previously suggested, lobbying firms may be incentivized to downplay the role they played in lobbying for human rights perceptions in formal FARA reports, knowing that they are often working for less than salubrious clients. In these cases, lobbying firms may instead note that they are working toward a more general campaign of public relations or image building. To see potential effects of this lobbying, we examine the 1996 (year t + 1) State Department and Amnesty reports for Chad.

Consistent with our statistical estimates, we find human rights more favorably treated in the State Department reports, but no similar treatment in the Amnesty International reports when there is lobbying. The PTS data shows that the State Department reports on Chad were assigned a score of “4” for many years leading up to this lobbying effort. However, in 1996, after the increase in lobbying efforts, the State Department reports are coded as a more favorable “2” for Chad, whereas Amnesty International continued to score the country “4.” The two-point difference in scale greatly reduces the chance that the difference in metrics could be solely attributable to measurement error (as one could argue with a one-point difference). It is worth noting that prior to 1995, there are no other recorded efforts of Chad hiring lobbyists. It is particularly noteworthy, then, that in the year after their lobbying efforts, we see a significant change in the interpretation of human rights in Chad.

When examining the State Department and Amnesty reports concerning Chad, there are clear differences highlighted in each report. The rosier State Department report emphasizes government behavior to reduce and eliminate torture (emphasis added):

The Constitution specifically prohibits torture and degrading or humiliating treatment; however, members of the security forces continued to commit some abuses. The Government took steps to halt acts of brutality by its security forces when President Deby appointed former Justice Minister Youssouf Togoimi Minister of the Armies in December 1995 in an effort to reform the military services. Deby and Togoimi made significant efforts to end military corruption and abuse. Human rights advocacy groups reported only scattered abuses by the military in 1996, and credit Togoimi's reform actions.

We include the bolded terms to emphasize how the State Department's report might be more favorable when it comes to torture. The report emphasizes effort and potential change from previously egregious torture records, and irregular rather than systematic reports of torture. In addition, the State Department report pays particular attention to the institutions in place to prevent human rights abuses.

On the other hand, the Amnesty report emphasizes myriad specific cases of torture and does not begin with a positive frame for otherwise egregious acts. The summary of the report states:

Dozens of suspected opponents and critics of the government. Some of the prisoners of conscience were detained without charge or trial. One prisoner of conscience was convicted after an unfair trial. Torture, including rape, and ill treatment were widespread; several people may have died under torture. One person died in custody apparently as a result of harsh prison conditions. Four members of an armed opposition group arrested in Sudan "disappeared" after being forcibly returned to Chad. Scores of people were extra-judicially executed. Armed opposition groups were reportedly responsible for grave abuses.

Thus, despite drawing on similar data and common knowledge about constitutional reforms (which occurred in early-to-mid 1996), Amnesty and the State Department describe very different situations with respect to torture. The State Department's report emphasizes government actions and attempts to contextualize remaining torture. While there is no “smoking gun” showing that the lobbyist-facilitated meetings between Chadian officials and US government officials led directly to this outcome, the changed emphasis in the State Department reports on government efforts to improve human rights is a clear observable implication of such meetings.

Conclusions

We examined whether lobbying by foreign governments can affect US foreign policy via US State Department human rights reports. These reports matter a great deal, as they are used to inform the allocation of foreign aid, sanctions policy, and conditions on trade policy. Moreover, these human rights reports profoundly shape academic findings about the determinants of respect for human rights; alongside ratings from Amnesty International, they serve as a basis for key datasets used by scholars, such as the Political Terror Scale and Fariss’ (2014) more recent measures.

Our findings demonstrate that foreign governments work hard to alter the information that feeds the creation of human rights reports. They hire US-based lobbyists to provide information to the many groups that can influence these reports. Specifically, they provide direct information to US government officials—including members of Congress, their staffers, and US State Department officials—to contextualize human rights practices in their countries. Foreign lobbyists also supply indirect information—to audiences such as journalists and the wider public—to influence a country's public relations image. This broader information can even create implicit bias in favor of the foreign government; in other words, we find strong evidence that the information supplied by lobbyists shapes reports even when officials try to ignore it.

Our research contributes to growing scholarship on who influences US foreign policy (Jacobs and Page 2005). This emerging research acknowledges the importance of looking at how non-state actors—such as think tanks (Stone 1996; Abelson 2006) and NGOs (Slaughter 1997; Risse 2007)—affect American policy abroad. We show that this list of key non-state foreign policy influencers should also include foreign lobbyists.

Our findings also speak to the burgeoning new literature on the interdependence approach (Farrell and Newman 2014) that focuses on the shifting boundaries of political contestation between domestic and international institutions. Our results suggest an endogenous process in which foreign governments attempt to influence US human rights reports, which the United States then uses to judge those very same foreign governments, and which then shape the next round of lobbying.

Moreover, this article speaks to the wider pattern of performance indicators in ranking and rewarding governments abroad (Kelley and Simmons 2015). The formation of these metrics can affect key conclusions and decisions in international relations (Kerner, Jerven, and Beatty 2017). We provide further evidence that the construction of these reports is a political process and that governments can manipulate their ratings. This tracks with Clark and Sikkink's (2013, 540) reminder that “researchers should beware of possible ‘information effects’: patterns in the data stemming from the process of information collection and interpretation, rather than the process that actually gives rise to human rights violations or their mitigation.” Moreover, much of the existing work on country rankings focuses on evaluating the effects of global assessment tools, but the literature thus far says less about the politics of generating those rankings by countries or international organizations. And while some scholars argue that lobbying could be a factor in those politics (Cooley and Snyder 2015, 5, 31), we are the first to examine this mechanism empirically.

Despite all of this, we caution against interpreting our findings to mean that human rights ratings are completely unreliable. Some of the problems that arise in human rights reporting can be resolved by using multiple sources (see Fariss 2014). Indeed, we identify a way to assess the extent of the “gaming” that exists in creating measurements of international human rights, at least in the case of State Department reports.28 Perhaps counterintuitively, our research thus serves as a nice rejoinder to the claim that manipulation by foreign governments makes quantitative indicators useless for assessing human rights practices or foreign policy more generally.

Future research should evaluate the impact of foreign lobbying on other country-level rankings that shape US foreign policy. Since the mid-1990s, scholars and organizations have developed indicators for a wide range of phenomena, including human trafficking, failed states, transparency, corruption, and poverty levels (Davis 2012; Cooley and Snyder 2015). Commentators sometimes question the objectivity of many of these measures,29 and thus scholars should examine whether, and when, foreign lobbying plays a role in influencing these other metrics.

Notes

Author’s note: We thank Amanda Murdie, Courtney Hillebrecht, Jessica L.P. Weeks, Eleanor Powell, and attendees at the University of Chicago Program on International Politics and Economics (PIPES) workshop, the University of Wisconsin–Madison International Relations (IRC) Colloquium, the Kansas State University IR workshop, the Stanford University IR workshop, the University of Texas IR workshop, the American Political Science Association (APSA) annual meetings, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. For valuable research assistance, we thank Fay Booker, Roberta Braga, Claire Champion, Alexander Holland, Jonathan Padway, and Rachel Sobotka. This work was supported by NSF Grant 1023967. All errors remain our own.

Author Biographical

Jon Pevehouse is the Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests are in the field of international political economy, American foreign policy, international organizations, and political methodology.

Felicity Vabulas is an assistant professor of international studies at Pepperdine University. Her research focuses on the political economy of international organizations and US foreign policy, and highlights the changing ways that states cooperate, negotiate, and influence world affairs.

Footnotes

http://www.cfr.org/human-rights/department-state-country-reports-human-rights-practices/p10115, accessed 14 August 2014. Throughout the years, State also added reports for Western Sahara, Taiwan (even after it was dismissed from the UNGA), Hong Kong, and Macau.

https://www.amnesty.org/en/who-we-are/, accessed 26 June 2017.