-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Emma van der Weijde, Michiel Kuijpers, Wobbe Bouma, Massimo A Mariani, Theo J Klinkenberg, Staged single-port thoracoscopic R2 sympathicotomy as a reproducible, safe and effective treatment option for debilitating severe facial blushing, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 35, Issue 5, November 2022, ivac257, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivac257

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Our goal was to investigate the safety, feasibility, success rate, complication rate and side effects of staged single-port thoracoscopic R2 sympathicotomy in the treatment of severe facial blushing. Facial blushing is considered a benign condition; however, severe facial blushing can have a major impact on quality of life. When nonsurgical options such as medication and psychological treatments offer no or insufficient relief, surgical treatment with thoracoscopic sympathicotomy should be considered.

All patients who underwent a staged thoracoscopic sympathicotomy at level R2 for severe facial blushing between January 2016 and September 2021 were included. Clinical and surgical data were prospectively collected and analysed.

A total of 16 patients with low operative risk (American Society of Anesthesiologists class 1) were treated. No major perioperative complications were encountered. One patient experienced postoperative unilateral Horner’s syndrome that resolved completely after 1 week. Two patients experienced compensatory hyperhidrosis. The success rate was 100%. One patient experienced a slight recurrence of blushing symptoms after 3 years that did not interfere with their quality of life. All patients were satisfied with the results and had no regrets of having undergone the procedure.

Staged single-port thoracoscopic R2 sympathicotomy is a reproducible, safe and highly effective surgical treatment option with low compensatory hyperhidrosis rates and the potential to significantly improve quality of life in carefully selected patients suffering from severe facial blushing. We would like to increase awareness among healthcare professionals for debilitating facial blushing and suggest timely referral for surgical treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Facial blushing is an expression of emotion caused by the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. It has been defined as uncontrollable reddening of the face, neck and upper chest that is experienced in reaction to real or perceived social attention [1]. The exact prevalence or incidence rates of facial blushing are unknown; however, Nicolaou et al. have shown that 75% of all enquiries on a generalized hyperhidrosis, blushing and sympathectomy information website came from patients suffering from facial blushing and only 25% came from patients with primary hyperhidrosis [2].

Facial blushing in its physiological form is often perceived as a symptom of social phobias or anxiety disorders. The latter are found in around 10% of the general population; of these patients, 50% report facial blushing as a prominent symptom [3, 4]. Severe facial blushing may, however, not be the result but the cause of social phobias or anxiety by creating avoidance behaviours. It can have a profound influence on a patient’s social, relational and professional life, resulting in severe impairment of quality of life and social isolation. The general practitioner is often the first medical professional who encounters these patients. It is important to realize that for strictly selected cases, in whom no underlying medical condition is evident [5, 6] and for whom psychoeducation, cognitive behavioural therapy or medication has offered no or insufficient improvement, there is a surgical treatment option in the form of thoracoscopic sympathicotomy.

Thoracoscopic sympathicotomy for treatment of palmar and axillary hyperhidrosis has proven to be a reproducible, safe and effective treatment modality [7–9]. However, the literature on thoracoscopic sympathicotomy for facial blushing is limited. The first publications on the treatment of facial blushing involved patients with craniofacial hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating of the entire face or forehead) and showed that these patients were also relieved from attacks of facial blushing as a side effect [10, 11].

The current study was performed to investigate the success rate, perioperative complications and side effects of staged thoracoscopic R2 sympathicotomy in the treatment of severe facial blushing.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

All patients referred to us with complaints of severe facial blushing between 2016 and 2021 were considered for treatment. The following criteria were required to qualify for surgery: (i) Facial blushing on a daily basis; (ii) a strong negative influence on self-image, social life and professional life; (iii) unsuccessful treatment results of non-surgical options, such as medication or cognitive (behavioural) therapies. Patients underwent preoperative counselling, were thoroughly informed about the procedure and its possible side effects and complications and were given a 1-day reflection period. Patients received oral pain medication for a week postoperatively and were instructed to leave the airtight bandage on for 3 days. After 2 weeks, a standardized telephone consultation was scheduled. If the procedure was successful and no or transient Horner’s syndrome was present, the patient was scheduled for a contralateral procedure with a minimal interval of 4–6 weeks. All patients were followed up again in October 2021 by the same standardized telephone interview to evaluate their current status.

Surgical technique

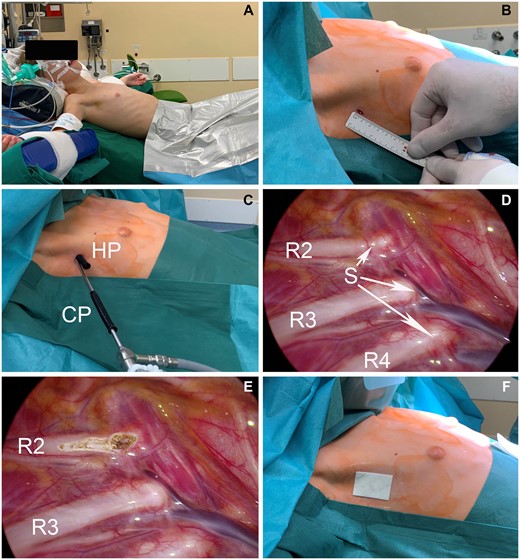

All procedures were performed by 2 surgeons with extensive experience in thoracoscopic sympathicotomy for a broad spectrum of indications (over 1500 procedures) [9, 12–14]. Procedures were performed with the patients under general anaesthesia and with single-lumen intubation. Patients were positioned in the beach-chair or semi-Fowler position (Fig. 1A), and the axillary thoracic entry side was infiltrated locally with bupivacaine with adrenalin. A small (1 cm) skin incision was made just posterior to the axillary fold (Fig. 1B). A stump trocar was introduced under apnoea in order to gain intrathoracic access. A ribbed hard-plastic work port was used to introduce the camera (Fig. 1C). After the lung was collapsed and the camera was introduced, the ribs and the sympathetic nerve were identified (Fig. 1D). The camera working port was pulled back over the camera shaft, and a new cautery hook working port was inserted directly adjacent to the camera shaft (Fig. 1C). The sympathetic nerve was transected at the level of R2. This transection was then widened for 2 cm lateral to the nerve to include accessory fibers (Fig. 1D, E). A drain was introduced; after recruitment of the lung, the drain was removed under positive end-expiratory pressure of 30 cm H2O. The skin was closed with Monocryl 3.0 suture and taped airtight with a double plastic-coated sticker (Fig. 1F). A postoperative chest X-ray was performed for all patients. Because patients were referred to us from the entire country, they were observed overnight to monitor pain, dyspnoea or other postoperative problems. If Horner’s syndrome was present, an evaluation was performed after 4–6 weeks to see if this condition was permanent or transient. Patients in whom there was no or transient Horner’s syndrome were scheduled to receive the same treatment on the contralateral side.

Surgical technique of staged single-port thoracoscopic R2 sympathicotomy for facial blushing. (A) Patient positioned in the beach-chair position or semi-Fowler position, seated at a 45° angle, with both arms spread out. (B) Marked incision just posterior to the axillary/mammary fold. (C) The positioning of the camera port and the cautery hook port through the same incision. (D) Thoracoscopic view of the right superior mediastinum with identification of the sympathetic nerve running along the neck of the ribs (R2–R4). (E) Thoracoscopic view after R2 sympathicotomy. (F) Double plastic-coated sticker placed over the incision site to prevent air re-entry. CP: camera port; HP: hook port; S: sympathetic nerve.

Ethical statement

The Dutch Medical Ethics Review Board (METC UMCG 2021) waived the need for informed consent.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are reported as the standard mean with standard deviation (SD).

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 29 patients were seen in our outpatient clinic for screening. Sixteen patients qualified for staged single-port thoracoscopic R2 sympathicotomy. Half of the patients were male (50%); the mean age was 33 years (range, 21–52 years). All patients were discharged the day after the intervention.

Clinical outcomes

Full relief of symptoms was obtained in all patients. The mean time between the first and second procedure was 83 days (SD 46.3 days).

One patient had an asymptomatic apical postoperative pneumothorax, which was treated conservatively. One patient had transient unilateral Horner’s syndrome; the patient fully recovered within 1 week. Patients experienced minimal postoperative pain, with a mean visual analogue scale of 1.4 (SD 2.1). The mean hospital stay was 1.2 days (SD 0.4).

The mean follow-up time was 23 months (SD 2.9). During follow-up, 2 patients experienced compensatory hyperhidrosis (CH). One patient described the CH as severe and was successfully started on oral oxybutynin. One patient reported recurrent symptoms of facial blushing after 3 years; however, symptoms were less severe than before the initial surgery. All patients were fully satisfied with the obtained result and did not regret having undergone the procedure.

DISCUSSION

Facial blushing, defined as the reflection of vasodilatation of cutaneous blood vessels elicited by emotional stimuli, is mostly considered a physiological and benign condition. However, severe facial blushing can have a detrimental effect on a patient’s quality of life. Nonsurgical treatment options such as medication and/or psychological treatment are still considered as a first-line treatment option. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or beta blockers are used in the treatment of facial blushing. Sparse literature describes some reduction of blushing obtained with medication, although the side effects are considerable [15]. A prospective study comparing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and thoracic sympathectomy showed that surgery was associated with a greater reduction of blushing and greater patient satisfaction compared to medication [16]. Cognitive behavioral treatment and group therapy are the most commonly applied psychological treatments for social phobias, a psychological disorder often associated with facial blushing. However, therapy is time-consuming and focuses mostly on complicated phobias. Only a few studies have investigated the treatment effect on the specific fear of blushing [17–19]. Percutaneous phenol blocks of the sympathetic nerve have traditionally been used to treat pain syndromes of the upper extremities. In some cases these injections were also used to treat hyperhidrosis, Raynaud syndrome or arrhythmias, with either computed tomography or ultrasound guidance. The injections were successful in small cohorts. However, the effects are temporary and have complication risks similar to those of surgery [20–21].

Thoracic sympathicotomy is a well-established treatment modality for severe focal palmar, axillary and craniofacial hyperhidrosis [7–9]. During the treatment of craniofacial hyperhidrosis, it was noted that patients were simultaneously relieved from attacks of facial blushing [11]. In all patients with severe facial blushing who experience no or insufficient symptom relief with medication or cognitive behavioral treatment, R2 sympathicotomy should be considered. Underlying medical conditions causing facial blushing should be ruled out. Successful surgical treatment allows patients to resume their lives unhindered by the social, relational and professional impacts of the disorder. Results seem most promising in patients suffering from rapid-onset facial blushing [22]. In our cohort, we have an initial success rate of 100%, with 1 patient reporting recurrence of less severe symptoms after 3 years. Similar success rates have been reported in the literature, with rates of 78–90% [23–25]. Our success rate of 100% might be caused by our strict patient selection criteria and the small number of patients treated.

No perioperative complications, such as pneumothorax requiring a chest drain, were seen in our study. Transient unilateral Horner’s syndrome did occur in 1 patient. In the literature, Horner’s syndrome occurs in about 0–4% of patients having R2 and R2-3 sympathicotomies [23–25].

The most commonly reported side effect of this procedure is CH, with a varying incidence of 30–70% [23–26]. This variation in reported incidence of CH strongly depends on the definition used. Whereas some studies report all findings of CH, others only report CH when patients experience severe symptoms that require a change of clothes multiple times a day [24, 25]. In our cohort, 2 patients (12.5%) reported CH. One patient reported mild CH and 1 patient reported severe CH, requiring treatment with oxybutynin.

Even in series in which the CH rate was high, patients did not regret having undergone the procedure [24, 25]. In our cohort, 2 patients experienced CH; neither patient regretted having the treatment. However, long-term studies have shown that a patient’s satisfaction with the surgical results may decrease over time [22]. It is believed this fading satisfaction is caused by the persisting symptoms of CH, whereas the memories regarding the suffering from the severe blushing fade over time [22].

To improve long-term results, the risk of developing CH after thoracoscopic sympathicotomy should be minimized. Three recommendations can be made to minimize the risk of developing CH. (i) Perform an isolated R2 sympathicotomy. Licht et al. noted a significantly higher incidence of CH in the group in which the sympathetic nerve was cut at the R2 and R3 levels compared to the group in which it was cut only at the R2 level (95% vs 83%, P = 0.02) [23]. (ii) Perform a sympathicotomy instead of a historically true sympathectomy, removing a segment of the sympathetic chain including 1 or more ganglia [27–29]. It is hypothesized that severing sympathetic reflex arcs that run through the ganglia to the hypothalamus leads to CH through dysfunctional sweat regulation in the affected body parts [30]. This finding is corroborated by earlier studies that show higher rates of dissatisfaction and severe CH in patients treated for axillary primary focal hyperhidrosis compared to patients treated for palmar primary focal hyperhidrosis [12, 31] and adds to the understanding that the ganglia should be left untouched. (iii) CH is probably less common in patients treated with a two-stage procedure compared to a one-stage procedure, in which both sides are treated during the same operation [32].

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that staged single-port thoracoscopic R2 sympathicotomy is a reproducible, safe, highly effective surgical treatment option with low rates of CH in carefully selected low-risk patients suffering from severe facial blushing. When non-surgical treatment options have failed, referral to a centre with extensive experience in thoracoscopic sympathicotomy is warranted. General practitioners should be aware that R2 sympathicotomy is a realistic treatment option in this group, in which the burden of debilitating facial blushing has been overlooked long enough.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Massimo A. Mariani is a consultant for Artivion, Atricure, CorCym and Medtronic. He has received grants from Abbott, Atricure, Getinge, Edwards and St. Beatrixoord. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.