-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tara M. Connelly, Walenty Kolcow, Dave Veerasingam, Mark DaCosta, A severe penetrating cardiac injury in the absence of cardiac tamponade, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 24, Issue 2, 1 February 2017, Pages 286–287, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivw342

Close - Share Icon Share

Penetrating cardiac injury is rare and frequently not survivable. Significant haemorrhage resulting in cardiac tamponade commonly ensues. Such cardiac tamponade is a clear clinical, radiological and sonographic indicator of significant underlying injury. In the absence of cardiac tamponade, diagnosis can be more challenging. In this case of a 26-year old sailor stabbed at sea, a significant pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade did not occur despite an injury transversing the pericardium. Instead, the pericardial haemorrhage drained into the left pleural cavity resulting in a haemothorax. This case is notable due to a favourable outcome despite a delay in diagnosis due to a lack of pericardial effusion, a concomitant cerebrovascular event and a long delay from injury to appropriate medical treatment in the presence of a penetrating cardiac wound deep enough to cause a muscular ventricular septal defect and lacerate a primary chordae of the anterior mitral leaflet.

CASE

A 26-year old male sailor was involved in an altercation on board his ship 100 miles offshore. A 3-cm knife entry point was noted in the fourth intercostal space 6–7 cm to the left of the midline. He was transferred by air ambulance to the closest medical facility, a community hospital 45 min away.

INVESTIGATIONS AND MANAGEMENT

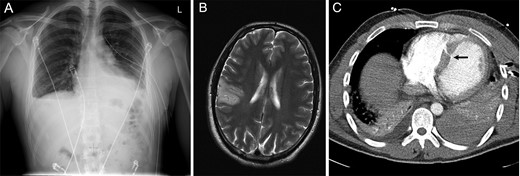

Radiological Imaging. (A) Chest X-ray showing a large left-sided pleural effusion. (B) MRI of the brain demonstrated a large parietal watershed area infarct. (C) CT Thorax demonstrating a moderate left-sided pleural effusion/haemothorax and a VSD (arrow).

Echocardiograms and intraoperative images. (A) Intraoperative image demonstrating the knife entry point in the free wall of the right ventricle; (B) Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrating a VSD in the middle portion of the muscular part of the septum (demonstrated by the blue jet). (C) Transthoracic echocardiogram after VSD occlusion.

Routine cardiopulmonary bypass via a median sternotomy and a transseptal approach was performed with mild hypothermia with cooling to 32°C and routine tubing for ascending aorta arterial and bicaval venous cannulation. Blood and cardioplegia were delivered via the antegrade and retrograde routes. The epicardial entry point was immediately visible on the free RV wall anteriorly (Fig. 2B). This point was already healed, thus suturing was not required. The mitral valve was repaired using a size 22 neochordae loop (W.L. Gore & Associates, AZ, USA). Attempted VSD closure was performed with a pledgeted prolene suture with a transtricuspid valve approach into the right ventricle. Bypass and cross-clamping time were 111 and 79 min, respectively. Postoperative TOE demonstrated a competent mitral valve, mild MR and an unchanged muscular VSD with a severe left to right shunt. His recovery was uneventful with no deterioration in his stroke symptoms. A subsequent percutaneous closure of his significant residual traumatic VSD was performed using an Amplatzer closure device (St. Jude Medical, MN, Fig. 2C). After 3 days in the cardiac intensive care unit, he was transferred to the ward. Upon discharge on postoperative day 21, only subtle residual arm motor impairment remained. He returned to his home country for recovery.

DISCUSSION

This case is notable due to the favourable outcome despite a concomitant CVA, a long delay from injury to appropriate medical treatment and the lack of pericardial tamponade in the presence of a penetrating cardiac wound deep enough to cause a muscular VSD and lacerate an anterior mitral leaflet primary chordae. Initially we thought the CVA was caused by prolonged hypotension on the ship; however, the injury was more focal (rather than in a watershed area as typically seen in cases of prolonged hypotension). Thus, the more likely aetiology was muscle or clot emboli caused by the knife. Data on the optimal timing of bypass surgery after CVA are limited. Thus, a multidisciplinary cooperation was required to determine the ideal time to minimize the risk of bleeding and re-infarction.

Cardiac stab injury is predominantly sustained by males, non-accidental and fatal [1, 2]. Mortality reported in large series approaches 60% [2, 3]. In the absence of pericardial tamponade, fatality rates are higher. In our case, the distances to the nearest hospital and to our trauma centre greatly increased the mortality risk. The pericardial effusion drained into the left pleural space, creating a haemothorax instead of a cardiac tamponade. Hypotension sealed the injured muscle of the right ventricle. Thus, no effusion, VSD or obvious injury was seen on initial echocardiography. The rising troponin levels and a marked systolic murmur indicated a high likelihood of myocardial injury leading to a further echocardiogram and re-evaluation of the CT thorax. This case highlights the importance of a high index of suspicion for cardiac injury based on the mechanism, even in the absence of pericardial tamponade.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Luther Keita, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University College Hospital, Galway Ireland for his assistance with the images in the case report.

Conflict of interest: none declared.