-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tatsuya Tarui, Norihiko Ishikawa, Hiroshi Ohtake, Go Watanabe, Totally endoscopic robotic resection of left atrial myxoma with persistent left superior vena cava, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 23, Issue 1, July 2016, Pages 174–175, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivw059

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 68-year old man with a cardiac tumour was admitted for robotic tumour resection using the da Vinci S Surgical System. While undergoing preoperative examination, he was found to have a persistent left superior vena cava. After general anaesthesia and single-lung ventilation, cardiopulmonary bypass was established, with venous drainage through bilateral internal jugular and right femoral veins and arterial return through the right femoral artery. Robotic tumour resection was performed by four ports in the right chest. There were no difficulties during the operation, and successful tumour resection was achieved with satisfactory margins. He was discharged without complications. Persistent left superior vena cava is very rare, but if diagnosed preoperatively and an appropriate operative plan is made, robotic cardiac surgery can be performed safely. With robotic surgery, cardiac tumour resection can be feasibly performed, with cosmetic benefits.

CASE REPORT

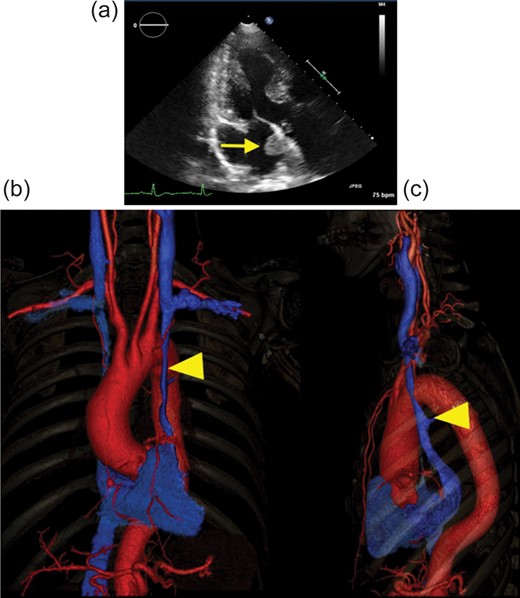

A 68-year old asymptomatic man was referred to our institution for suspicion of a cardiac tumour measuring 19×15×17 mm in the left atrium (Fig. 1a). Robot-assisted tumour resection using da Vinci S Surgical System (da Vinci) was scheduled. However, preoperative computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC) (Fig. 1b and c). There was no communication between the left and the right SVCs.

(a) Preoperative echocardiograph in three-chamber view. Arrow shows the cardiac tumour in the left atrium. (b and c) 3D vascular image of preoperative CT scan: (b) front view and (c) left lateral view. The red vessel shows the artery, and the blue vessel shows the vein. Arrow head points to the PLSVC. There was no major communication between the left and the right SVCs. CT: computed tomographic; PLSVC: persistent left superior vena cava.

Tumour resection was performed using da Vinci, with approval from the Institutional Review Board of NewHeart Watanabe Institution and informed consent. The patient was placed in supine position. Under general anaesthesia with double-lumen endotracheal intubation, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was established, with venous drainage (PCKC-V-14D; Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) through bilateral internal jugular and right femoral veins and arterial return (FEMII 020A; Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) through the right femoral artery. Four ports were placed in the right chest of the patient. The left arm of the robot was inserted through the fourth intercostal space (ICS) in the anterior axillary line (AAL) and the right arm was inserted through the sixth ICS in the AAL. A service port was placed in the fourth ICS in the AAL. The camera port was inserted through the fourth ICS in the midclavicular line.

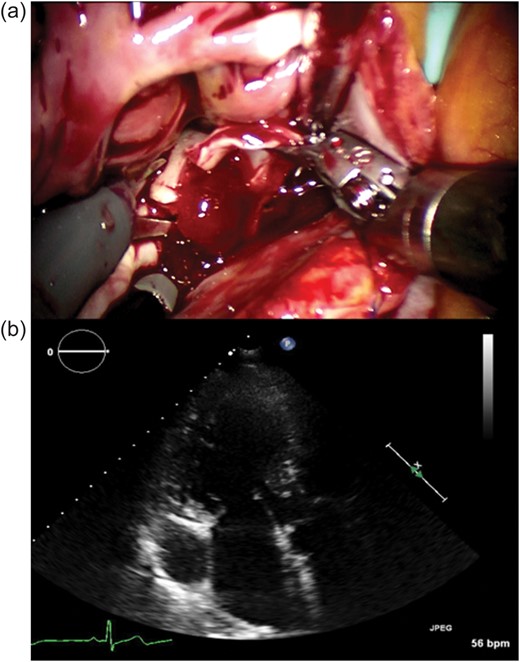

CPB was initiated, and the right superior vena cava was occluded with a small clamp. The persistent SVC was not occluded. Ventricular fibrillation was induced using a combined method of electrical fibrillator, injection of potassium and hypothermia of 32°C, without cross-clamping. After the right atriotomy, the incision of the atrial septum was made under transoesophageal echocardiographic (TOE) guidance, with a 1 cm margin from the stalk of the tumour. The tumour was found to be 20 mm in diameter (Fig. 2a) and was suspected to originate from the atrial septum, to which it was connected to via a stalk. The tumour was resected with its attachment to the atrial septum. The atrial septum was then closed with a 4-0 polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex suture; W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) running suture. The right atriotomy was likewise closed with a 4-0 polytetrafluoroethylene running suture. Weaning from the CPB was performed smoothly, without any problems. Total operative time was 152 min, CPB time was 66 min and ventricular fibrillation time was 10 min. He was discharged on the seventh postoperative day without complications. On histological examination, the tumour was diagnosed to be a benign cardiac myxoma. Echocardiography after 6 months revealed no recurrence (Fig. 2b).

(a) Intraoperative image. Robotic tumour resection was performed by da Vinci. The arrow shows the tumour, which was found to be 20 mm in diameter, and was resected with its attachment to the atrial septum. (b) Preoperative echocardiograph in three-chamber view. There is no recurrence of the cardiac tumour.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, robotic cardiac surgery in a patient with PLSVC is rare [1], and certain technique is required for safe surgery and CPB. Our technique of venous drainage from bilateral internal jugular and right femoral veins enabled successful tumour resection with no complications and no surgical difficulties during CPB.

PLSVC is a very rare venous malformation, occurring in 0.3–0.5% of the general population [2]. Performing cardiac surgery for patients with PLSVC, single drainage from the jugular vein is not sufficient to establish safe CPB and drainage. There are few reports of CPB in patients with PLSVC, and patients with PLSVC tend to have thicker coronary sinuses. If the drainage from the jugular vein is not adequate, surgical vision may be obstructed and congestion of the cerebral circulation can occur, which can lead to cerebral infarction. For this case, we obtained sufficient drainage and good surgical vision by accessing bilateral jugular and the right femoral veins. Thus, we recommend insertion of bilateral jugular venous drainage for cases of PLSVC. This allowed excision of the tumour with satisfactory margins.

Cardiac tumour resection by da Vinci has been reported to be a safe method by previous reports [3]. However, to perform the operation safely, a good operative field is inevitable. When PVLSC was not found preoperatively, the operator can manage the CPB during the operation in conventional surgery. However, it is very difficult for the operator to manage intraoperatively in robotic surgery, and can lead to discontinuation of the surgery. In the present report, the diagnosis was capable of detecting PLSVC by preoperative CT scan. This led us to insert bilateral jugular veins for venous drainage and to obtain a good operative field. Therefore, preoperative CT scan is very important in robotic surgery.

Previous reports were performed by either intraluminal balloon aortic occlusion or Chitwood's aortic clamp technique. However, for our patient, we opted to perform a cardiac surgery under ventricular fibrillation, for several reasons. Ventricular fibrillation is fast, can be performed without touching the aorta, and has the added advantage of avoiding postoperative bleeding and complications such as cerebral infarction. In our institution, we have established a safe technique of robotic cardiac surgery under ventricular fibrillation in closure of atrial septal defects [4].

In conclusion, bilateral jugular venous drainage is useful in a patient with PLSVC. Our report and technique can lead to the extended utilization of robotic cardiac surgery, with safe and feasible outcomes.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- heart neoplasms

- cardiopulmonary bypass

- persistent left superior vena cava

- endoscopy

- anesthesia, general

- femoral artery

- femoral vein

- surgical procedures, operative

- chest

- preoperative medical evaluation

- left atrial myxoma

- one lung ventilation

- robotic surgery

- robotic cardiac surgery

- blood outflow

- tumor excision