-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ludovic Melly, Brigitta Gahl, Ruth Meinke, Florian Rueter, Peter Matt, Oliver Reuthebuch, Friedrich S. Eckstein, Martin T.R. Grapow, A new cable-tie-based sternal closure device: infectious considerations, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 17, Issue 2, August 2013, Pages 219–224, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivt183

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To determine the difference in sternal infection and other infectious events between conventional wire and cable-tie-based closure techniques post-sternotomy in a collective of patients after cardiac surgery.

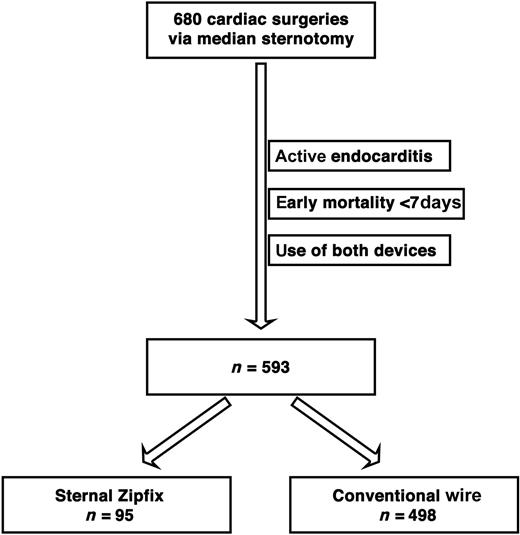

The sternal ZipFix™ (ZF) system consists of a biocompatible poly-ether-ether-ketone (PEEK) cable-tie that surrounds the sternum through the intercostal space and provides a large implant-to-bone contact. Between 1 February 2011 and 31 January 2012, 680 cardiac operations were performed via sternotomy at our institution. After the exclusion of operations for active endocarditis and early mortality within 7 days, 95 patients were exclusively closed with ZF and could be compared with 498 who were closed with conventional wires (CWs) during the same period. A multivariable logistic regression analysis, including body mass index, renal impairment and emergency as suspected confounders and inverse propensity weights was performed on the infection rate.

Total infection rate was 6.1%, with a total of 36 diagnosed sternal infections (5 in ZF and 31 in CW). Comparing ZF with CW with regard to sternal infection, there is no statistically significant difference related to the device (odds ratio: 0.067, confidence interval: 0.04–9.16, P = 0.72). The propensity modelling provided excellent overlap and the mean propensity was almost the same in both groups. Thus, we have observed no difference in receiving either ZF or CW. No sternal instability was observed with the ZF device, unlike 4/31 patients in the CW group. The overall operation time is reduced by 11 min in the ZF group with identical perfusion and clamping times.

Our study underlines a neutral effect of the sternal ZipFix™ system in patients regarding sternal infection. Postoperative complications are similar in both sternal closure methods. The cable-tie-based system is fast, easy to use, reliable and safe.

INTRODUCTION

The median sternotomy approach became popular in the early 1960s thanks to Julian et al. [1] and still remains the gold standard approach for cardiac procedures. Although many different sternal closing strategies after conventional cardiac surgery have been presented in the last decades, wire closure still remains the preferred technique despite expected disadvantages such as instability resulting in delayed sternal healing and increased risk of post-sternotomy mediastinitis [2, 3]. Sternal Zipfix™ (ZF) (Synthes GmbH, Oberdorf, Switzerland), a biocompatible poly-ether-ether-ketone (PEEK) cable-tie-based sternal closure device, was brought on the market in 2010. Reports on its impact on infection after cardiac surgery are still lacking. Nosocomial wound infections after sternotomy are a multifactorial and complex problem, and risk factors for the development of infections have been emphasized by several authors [4, 5]. Sternal dehiscence has been discussed for years to be a reason for infection [6] that can be potentially prevented using sternal ZF that surrounds the sternum through the intercostal space, providing a larger implant-to-bone contact and avoiding bone cut-through especially in patients at risk [7]. We report our clinical experience and the possible related infectious considerations of the cable-tie-based device.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective descriptive and comparative study at the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland with the objective of assessing the frequency of wound infection and sternal dehiscence post-sternotomy with regard to the closure technique itself. At our institution, sternotomies are usually closed with five stainless steel wires placed trans-sternally in a figure-of-eight interrupted transverse fashion [6]. Two senior surgeons started to use the sternal ZF closing device in February 2011. Here, we compare the conventional closure with stainless steel wires USP 7 (Fumedica, Reichshof, Germany) with the PEEK-based sternal ZF device with regard to sternal infections. We collected all cardiac operations performed via sternotomy between 1 February 2011 and 31 January 2012. Since the main objective was to assess the incidence of infectious events related to the newly introduced device, we excluded operations for active endocarditis. According to Risnes et al. [8], sternal infections are usually diagnosed 1 week after operation (between Days 9 and 19) at the earliest, therefore we intentionally decided to exclude patients with an early mortality within 7 days. The sternal ZF system was used at the discretion of the surgeons. Because of anatomical reasons, some patients in the ZF group have received, in addition, one or two wires cranially or/and caudally as previously described [9]. Thirty-nine patients did not match one of the study groups because of the presence of both closure methods and have therefore been excluded (Fig. 1). Infections are recorded up to 12 months after the initial cardiac operation for the national surgical site infection surveillance system Swiss Noso by a dedicated study-nurse of the division for infectious diseases and hospital epidemiology who periodically reported to the cardiac surgery team. Sternal infections are then classified into three categories according to the criteria of Swiss Noso [10]. Due to comparability to international data, we merged deep and organ/space infections into two types of sternal infections:

superficial wound infection,

deep sternal infection including organ/space.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), categories as absolute numbers and percentage. To minimize bias, continuous variables were generally assumed as non-parametric and compared using Mann–Whitney U-test. Proportions were compared using Fisher's exact test. We used a logistic regression model to predict infection crudely and made adjustments with the inverse probability of treatment (IPT) as weight. The IPT is based on propensity scores derived with the following variables: body mass index (BMI), diabetes, smoking, pulmonary disease, renal impairment, ejection fraction, emergency and type of procedure. To avoid overfit, we included BMI, renal impairment and emergency as suspected confounders into the effect model [11, 12]. We performed a receiver operator characteristics diagram with area-under-the-curve (AUC) analysis to assess overall model fit of the multivariate logistic regression. All P-values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are two-sided. The statistical analysis has been conducted on Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 680 patients underwent cardiac surgery via sternotomy at our institution during the defined 1-year period. Ultimately, according to our exclusion criteria, we could compare 95 patients whose sternum was exclusively closed with sternal ZF with 498 patients who were closed with conventional wires (CWs). The mean age of the whole population was 66 years, with 76% of males. A total of 36 patients developed a sternal infection in a same gender proportion as the overall proportion, with 27 males and 9 females.

Concerning preoperative demographics, no major differences were found with regard to the cardiovascular risk factors and the typical influencing factors for sternal infection [13] with the exception of pulmonary disease (Table 1).

| Preoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, SD | 67 ± 11 | 66 ± 10 | 0.10 |

| BMI, kg/m2, SD | 27 ± 4 | 28 ± 5 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 40 (38) | 44 (217) | 0.57 |

| Dyslipidemia, % (n) | 70 (66) | 68 (340) | 0.15 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 81 (77) | 83 (416) | 0.13 |

| Smoking, % (n) | 56 (53) | 65 (325) | 0.08 |

| Reoperation, % (n) | 2 (2) | 7 (35) | 0.10 |

| CAD, % (n) | 64 (61) | 75 (374) | 0.12 |

| Pulmonary disease, % (n) | 14 (13) | 230 (116) | 0.04 |

| Renal impairment, % (n) | 7 (7) | 80 (41) | 0.99 |

| Neurovascular disease, % (n) | 10 (10) | 60 (30) | 0.08 |

| Preoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, SD | 67 ± 11 | 66 ± 10 | 0.10 |

| BMI, kg/m2, SD | 27 ± 4 | 28 ± 5 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 40 (38) | 44 (217) | 0.57 |

| Dyslipidemia, % (n) | 70 (66) | 68 (340) | 0.15 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 81 (77) | 83 (416) | 0.13 |

| Smoking, % (n) | 56 (53) | 65 (325) | 0.08 |

| Reoperation, % (n) | 2 (2) | 7 (35) | 0.10 |

| CAD, % (n) | 64 (61) | 75 (374) | 0.12 |

| Pulmonary disease, % (n) | 14 (13) | 230 (116) | 0.04 |

| Renal impairment, % (n) | 7 (7) | 80 (41) | 0.99 |

| Neurovascular disease, % (n) | 10 (10) | 60 (30) | 0.08 |

Renal impairment defined as a serum creatinin level >150 μmol/l.

BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease.

| Preoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, SD | 67 ± 11 | 66 ± 10 | 0.10 |

| BMI, kg/m2, SD | 27 ± 4 | 28 ± 5 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 40 (38) | 44 (217) | 0.57 |

| Dyslipidemia, % (n) | 70 (66) | 68 (340) | 0.15 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 81 (77) | 83 (416) | 0.13 |

| Smoking, % (n) | 56 (53) | 65 (325) | 0.08 |

| Reoperation, % (n) | 2 (2) | 7 (35) | 0.10 |

| CAD, % (n) | 64 (61) | 75 (374) | 0.12 |

| Pulmonary disease, % (n) | 14 (13) | 230 (116) | 0.04 |

| Renal impairment, % (n) | 7 (7) | 80 (41) | 0.99 |

| Neurovascular disease, % (n) | 10 (10) | 60 (30) | 0.08 |

| Preoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, SD | 67 ± 11 | 66 ± 10 | 0.10 |

| BMI, kg/m2, SD | 27 ± 4 | 28 ± 5 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 40 (38) | 44 (217) | 0.57 |

| Dyslipidemia, % (n) | 70 (66) | 68 (340) | 0.15 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 81 (77) | 83 (416) | 0.13 |

| Smoking, % (n) | 56 (53) | 65 (325) | 0.08 |

| Reoperation, % (n) | 2 (2) | 7 (35) | 0.10 |

| CAD, % (n) | 64 (61) | 75 (374) | 0.12 |

| Pulmonary disease, % (n) | 14 (13) | 230 (116) | 0.04 |

| Renal impairment, % (n) | 7 (7) | 80 (41) | 0.99 |

| Neurovascular disease, % (n) | 10 (10) | 60 (30) | 0.08 |

Renal impairment defined as a serum creatinin level >150 μmol/l.

BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease.

The perioperative data showed that similar procedures were performed in both groups. Although the CW group had more coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) the ZF group included more combined procedures including CABG. In total, 73 patients underwent a partial/total replacement of the aortic arch in deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) with no difference between groups. Total operation time (skin to skin) was 11 min shorter in the ZF group with otherwise identical perfusion and clamping times on average. The difference of 2% in the intraoperative ejection fraction is statistically significant but clinically irrelevant and can therefore be considered equal (Table 2).

| Intraoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic EuroSCORE, %, SD | 12 ± 15 | 12 ± 15 | 0.53 |

| EF, %, SD | 53 ± 11 | 51 ± 12 | 0.02 |

| Emergency, % (n) | 20 (19) | 23 (115) | 0.59 |

| Procedures, % (n) | 0.21 | ||

| CABG only | 33 (31) | 47 (232) | |

| Valve only | 17 (16) | 16 (80) | |

| Combined procedure | 51 (48) | 37 (186) | |

| DHCA, % (n) | 15 (14) | 12 (59) | 0.33 |

| Double IMA grafts, % (n) | 6 (6) | 5 (26) | 0.91 |

| With CPB, % (n) | 91 (86) | 91 (454) | 0.31 |

| Operation time, min, SD | 192 ± 48 | 203 ± 59 | 0.16 |

| Perfusion time, min, SD | 115 ± 43 | 113 ± 44 | 0.43 |

| Clamping time, min, SD | 78 ± 31 | 76 ± 37 | 0.54 |

| Intraoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic EuroSCORE, %, SD | 12 ± 15 | 12 ± 15 | 0.53 |

| EF, %, SD | 53 ± 11 | 51 ± 12 | 0.02 |

| Emergency, % (n) | 20 (19) | 23 (115) | 0.59 |

| Procedures, % (n) | 0.21 | ||

| CABG only | 33 (31) | 47 (232) | |

| Valve only | 17 (16) | 16 (80) | |

| Combined procedure | 51 (48) | 37 (186) | |

| DHCA, % (n) | 15 (14) | 12 (59) | 0.33 |

| Double IMA grafts, % (n) | 6 (6) | 5 (26) | 0.91 |

| With CPB, % (n) | 91 (86) | 91 (454) | 0.31 |

| Operation time, min, SD | 192 ± 48 | 203 ± 59 | 0.16 |

| Perfusion time, min, SD | 115 ± 43 | 113 ± 44 | 0.43 |

| Clamping time, min, SD | 78 ± 31 | 76 ± 37 | 0.54 |

EF: ejection fraction as assessed by transoesophageal echocardiography by the anaesthesiologist in the operation theatre; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; DHCA: deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, 26°C by elective surgeries and 20°C in the case of emergencies; CPB: cardiopulmonal bypass; IMA: internal mammary artery.

| Intraoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic EuroSCORE, %, SD | 12 ± 15 | 12 ± 15 | 0.53 |

| EF, %, SD | 53 ± 11 | 51 ± 12 | 0.02 |

| Emergency, % (n) | 20 (19) | 23 (115) | 0.59 |

| Procedures, % (n) | 0.21 | ||

| CABG only | 33 (31) | 47 (232) | |

| Valve only | 17 (16) | 16 (80) | |

| Combined procedure | 51 (48) | 37 (186) | |

| DHCA, % (n) | 15 (14) | 12 (59) | 0.33 |

| Double IMA grafts, % (n) | 6 (6) | 5 (26) | 0.91 |

| With CPB, % (n) | 91 (86) | 91 (454) | 0.31 |

| Operation time, min, SD | 192 ± 48 | 203 ± 59 | 0.16 |

| Perfusion time, min, SD | 115 ± 43 | 113 ± 44 | 0.43 |

| Clamping time, min, SD | 78 ± 31 | 76 ± 37 | 0.54 |

| Intraoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic EuroSCORE, %, SD | 12 ± 15 | 12 ± 15 | 0.53 |

| EF, %, SD | 53 ± 11 | 51 ± 12 | 0.02 |

| Emergency, % (n) | 20 (19) | 23 (115) | 0.59 |

| Procedures, % (n) | 0.21 | ||

| CABG only | 33 (31) | 47 (232) | |

| Valve only | 17 (16) | 16 (80) | |

| Combined procedure | 51 (48) | 37 (186) | |

| DHCA, % (n) | 15 (14) | 12 (59) | 0.33 |

| Double IMA grafts, % (n) | 6 (6) | 5 (26) | 0.91 |

| With CPB, % (n) | 91 (86) | 91 (454) | 0.31 |

| Operation time, min, SD | 192 ± 48 | 203 ± 59 | 0.16 |

| Perfusion time, min, SD | 115 ± 43 | 113 ± 44 | 0.43 |

| Clamping time, min, SD | 78 ± 31 | 76 ± 37 | 0.54 |

EF: ejection fraction as assessed by transoesophageal echocardiography by the anaesthesiologist in the operation theatre; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; DHCA: deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, 26°C by elective surgeries and 20°C in the case of emergencies; CPB: cardiopulmonal bypass; IMA: internal mammary artery.

Postoperative complications as listed in Table 3 were reasonable and definitely similar in both groups with no influence on the intensive care unit (ICU) or the total hospital stay. Of the 2 patients who died within 30 days in the ZF group, only 1 had developed a sternal infection earlier; the other died from a sepsis of abdominal origin and the sternum was never reopened. In the CW group, 6 of 7 patients had their sternum reopened because of infection at the time of death. A trend was observed with less blood products (fresh frozen plasma, thrombocytes and erythrocytes concentrates) given postoperatively (ZF 22%, CW 29%, P = 0.11) and in particular, the need for transfusion was reduced in the ZF group.

| Postoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| All blood products | 22 (21) | 29 (145) | 0.13 |

| Only red blood cells concentrates, % (n) | 19 (18) | 27 (135) | 0.79 |

| 1 concentrate | 8 (8) | 8 (42) | |

| 2–5 concentrates | 8 (8) | 15 (75) | |

| >5 concentrates | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | |

| Re-exploration for bleeding, % (n) | 1 (1) | 2 (11) | 0.87 |

| Myocardial infarction, % (n) | 1 (1) | 1 (6) | 0.99 |

| Pneumothorax, % (n) | 2 (2) | 4 (18) | 0.53 |

| Postoperative delirium, % (n) | 13 (12) | 13 (65) | 0.59 |

| Renal function, % (n) | 21 (20) | 21 (104) | 0.58 |

| Overall mortality at 30 days, % (n) | 3 (3) | 1 (7) | 0.20 |

| ICU stay, days, SD | 3 ± 4 | 3 ± 4 | 0.75 |

| Hospital stay, days, SD | 10 ± 7 | 11 ± 13 | 0.39 |

| Postoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| All blood products | 22 (21) | 29 (145) | 0.13 |

| Only red blood cells concentrates, % (n) | 19 (18) | 27 (135) | 0.79 |

| 1 concentrate | 8 (8) | 8 (42) | |

| 2–5 concentrates | 8 (8) | 15 (75) | |

| >5 concentrates | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | |

| Re-exploration for bleeding, % (n) | 1 (1) | 2 (11) | 0.87 |

| Myocardial infarction, % (n) | 1 (1) | 1 (6) | 0.99 |

| Pneumothorax, % (n) | 2 (2) | 4 (18) | 0.53 |

| Postoperative delirium, % (n) | 13 (12) | 13 (65) | 0.59 |

| Renal function, % (n) | 21 (20) | 21 (104) | 0.58 |

| Overall mortality at 30 days, % (n) | 3 (3) | 1 (7) | 0.20 |

| ICU stay, days, SD | 3 ± 4 | 3 ± 4 | 0.75 |

| Hospital stay, days, SD | 10 ± 7 | 11 ± 13 | 0.39 |

All blood products include fresh frozen plasma, thrombocyte concentrates, erythrocyte concentrates and others (fibrinogene, coagulation factors, etc.). The overall hospital stay is from the entry date to the discharge date. ICU: intensive care unit, the stay is measured in days and not in hours.

| Postoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| All blood products | 22 (21) | 29 (145) | 0.13 |

| Only red blood cells concentrates, % (n) | 19 (18) | 27 (135) | 0.79 |

| 1 concentrate | 8 (8) | 8 (42) | |

| 2–5 concentrates | 8 (8) | 15 (75) | |

| >5 concentrates | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | |

| Re-exploration for bleeding, % (n) | 1 (1) | 2 (11) | 0.87 |

| Myocardial infarction, % (n) | 1 (1) | 1 (6) | 0.99 |

| Pneumothorax, % (n) | 2 (2) | 4 (18) | 0.53 |

| Postoperative delirium, % (n) | 13 (12) | 13 (65) | 0.59 |

| Renal function, % (n) | 21 (20) | 21 (104) | 0.58 |

| Overall mortality at 30 days, % (n) | 3 (3) | 1 (7) | 0.20 |

| ICU stay, days, SD | 3 ± 4 | 3 ± 4 | 0.75 |

| Hospital stay, days, SD | 10 ± 7 | 11 ± 13 | 0.39 |

| Postoperative . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| All blood products | 22 (21) | 29 (145) | 0.13 |

| Only red blood cells concentrates, % (n) | 19 (18) | 27 (135) | 0.79 |

| 1 concentrate | 8 (8) | 8 (42) | |

| 2–5 concentrates | 8 (8) | 15 (75) | |

| >5 concentrates | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | |

| Re-exploration for bleeding, % (n) | 1 (1) | 2 (11) | 0.87 |

| Myocardial infarction, % (n) | 1 (1) | 1 (6) | 0.99 |

| Pneumothorax, % (n) | 2 (2) | 4 (18) | 0.53 |

| Postoperative delirium, % (n) | 13 (12) | 13 (65) | 0.59 |

| Renal function, % (n) | 21 (20) | 21 (104) | 0.58 |

| Overall mortality at 30 days, % (n) | 3 (3) | 1 (7) | 0.20 |

| ICU stay, days, SD | 3 ± 4 | 3 ± 4 | 0.75 |

| Hospital stay, days, SD | 10 ± 7 | 11 ± 13 | 0.39 |

All blood products include fresh frozen plasma, thrombocyte concentrates, erythrocyte concentrates and others (fibrinogene, coagulation factors, etc.). The overall hospital stay is from the entry date to the discharge date. ICU: intensive care unit, the stay is measured in days and not in hours.

The propensity modelling provided excellent overlap and the mean propensity was almost the same in both groups, and the probability intervals for both groups ranged from 0.04 to 0.4, median 0.15 or 0.18, respectively. Thus, we have observed no difference in receiving either ZF or CW. Total infection rate was 6.1% over the 12 months including both superficial wound infections and deep sternal infections, with a total of 36 diagnosed sternal infections (5 in SZ and 31 in CW). The use of ZF did not show significant influence on ‘overall’ infection (univariable odds ratio [OR]: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.32–2.21, P = 0.72, multivariable OR: 0.067, 95% CI: 0.04–9.162, P = 0.72). The c-statistic indicated that the model fit was compatible with the random one (AUC = 0.685), but as it corresponds very well to the crude OR, we feel safe to interpret this as an evidence against any influence of ZF. In fact, we received the same result for different models, including all independent variables from the propensity model as well as just the treatment and the inverse propensity weights. We ran the same analysis with ‘deep’ sternal infection as the dependent variable and observed no influence in the analysis (univariable OR: 1.33, 95% CI 0.49–3.63, P = 0.58, multivariable OR: 0.928, 95% CI 0.056–15.25, P = 0.96). Interestingly, of the 5 patients in the ZF group who developed an infection, 2 could keep their sternal closure device in place and only a subcutaneous debridement was performed with successful clinical course afterwards, 2 could be closed later after a vacuum-assisted therapy with either CW or new ZF and only 1 needed a complex closure with a plate osteosynthesis. If the CW patients developed a sternal infection, they remained slightly longer hospitalized (23 ± 28 vs 19 ± 8 days for the ZF group, P = 0.76). No sternal instability was observed with the ZF device, unlike 4/31 patients in the CW group who needed the CW to be tightened up. Further infectious events such as pneumonia, sepsis and other treated infections are depicted in the descriptive statistics in the tables below with regard to the treatment groups (ZF vs CW; Table 4) or to the sternal infections (Table 5).

| Infectious considerations . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sternal infections | 5 (5) | 6 (31) | 0.99 |

| Superficial, % (n) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | |

| Deep, % (n) | 5 (5) | 4 (20) | 0.58 |

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 11 (11) | 7 (36) | 0.21 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 4 (4) | 2 (9) | 0.13 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 18 (17) | 14 (72) | 0.81 |

| Infectious considerations . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sternal infections | 5 (5) | 6 (31) | 0.99 |

| Superficial, % (n) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | |

| Deep, % (n) | 5 (5) | 4 (20) | 0.58 |

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 11 (11) | 7 (36) | 0.21 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 4 (4) | 2 (9) | 0.13 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 18 (17) | 14 (72) | 0.81 |

| Infectious considerations . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sternal infections | 5 (5) | 6 (31) | 0.99 |

| Superficial, % (n) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | |

| Deep, % (n) | 5 (5) | 4 (20) | 0.58 |

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 11 (11) | 7 (36) | 0.21 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 4 (4) | 2 (9) | 0.13 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 18 (17) | 14 (72) | 0.81 |

| Infectious considerations . | ZF (N = 95) . | CW (N = 498) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sternal infections | 5 (5) | 6 (31) | 0.99 |

| Superficial, % (n) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | |

| Deep, % (n) | 5 (5) | 4 (20) | 0.58 |

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 11 (11) | 7 (36) | 0.21 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 4 (4) | 2 (9) | 0.13 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 18 (17) | 14 (72) | 0.81 |

Postoperative infectious events according to the development of a sternal infection

| Infectious considerations . | Sternal infection (N = 36) . | Control group (N = 562) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 17 (6) | 7 (41) | 0.06 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 8 (3) | 2 (10) | 0.04 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 100 (36) | 12 (68) | 0.00 |

| Infectious considerations . | Sternal infection (N = 36) . | Control group (N = 562) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 17 (6) | 7 (41) | 0.06 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 8 (3) | 2 (10) | 0.04 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 100 (36) | 12 (68) | 0.00 |

Postoperative infectious events according to the development of a sternal infection

| Infectious considerations . | Sternal infection (N = 36) . | Control group (N = 562) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 17 (6) | 7 (41) | 0.06 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 8 (3) | 2 (10) | 0.04 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 100 (36) | 12 (68) | 0.00 |

| Infectious considerations . | Sternal infection (N = 36) . | Control group (N = 562) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia, % (n) | 17 (6) | 7 (41) | 0.06 |

| Sepsis, % (n) | 8 (3) | 2 (10) | 0.04 |

| Treated infections, % (n) | 100 (36) | 12 (68) | 0.00 |

DISCUSSION

At the time we introduced the new device at our institution, we observed an increase in the infection rate, which made us consider infections potentially related to the device. Before introducing ZF into standard clinical procedures, we conducted this retrospective study to determine the difference in sternal and other infections between CW and cable-tie-based closure techniques post-sternotomy in our collective of patients after cardiac surgery. Our main result shows no influence according to our effect model with regard to the ‘overall’ sternal infection for the biocompatible PEEK sternal closure device. With a total of 36 diagnosed sternal infections, a separate statistical analysis of either superficial or deep infection alone between both treatment groups is difficult and not reasonable due to the small sample size. From the same perspective, as there was no superficial infection diagnosed in the ZF group, we would be reluctant to state that ZF is protective against superficial infection; hence, we consider the non-significant OR towards ‘deep’ sternal infection in the ZF group as being due to the relatively small size of our sample.

Nevertheless, we did not succeed in presenting a significant reduction in postoperative sternal infection, which theoretically should be expected by reducing the number of patients with sternal dehiscence followed by secondary infection. Recently, Shaikhrezai et al. [14] described that deep sternal infection may be prevented by using nine or more paired fixation points when closing with standard peristernal wires, which was mostly the case in our CW control group since usually five-steel wires were placed in a figure-of-eight. Even if by ZF only five paired fixation points were anchored for technical reasons (no figure-of-eight possible), we did not observe any sternal instability at the time of diagnosis. In addition, in the 4 cases of the ZF group where mechanical re-animation was required, none developed a sternal instability. Even if this trend of anticipated superiority in terms of complete mechanical stability with potential saving on secondary infections may be stated [15], as only four dehiscent sterna were observed in ∼500 CW patients which corresponds to the incidence described by Sharma et al. [16]. A much larger cohort needs to be examined in order to confirm this preliminary result.

One difference observed between the two treatment groups preoperatively was the significantly higher proportion of pulmonary disease in the CW group. On the one hand, data on pulmonary disease are very heterogenous including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the presence or not of a steroid therapy. Indeed, subgroups should be recorded with regard to immunosuppression before drawing a conclusion on such a diversified pathology. On the other hand, 25% (n = 9) of the patients infected had a pulmonary disease vs 22% (n = 120) in the rest of the population, showing that in our cohort, the presence of a pulmonary disease does not influence significantly the development of infection (data not shown). With regard to other infectious events such as pneumonia, sepsis and other nosocomial infections, we did not find any statistical difference between both treatment groups. We confirm that sepsis and the overall rate of treated infections are quite relevant and highly correlate with the sternal infections in our cohort as sepsis and other infections are statistically significant when put in relation to sternal infections. On the contrary, pneumonia and pulmonary disease in general did not statistically influence the development of sternal infection in our collective. Possibly an explanation could be found in the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia, which correlates with the administration of blood products in a dose-dependent manner [17].

The use of the sternal ZF device is safe. First, with only around 6% of bilateral internal mammary arteries (IMAs) used similarly in both groups, neither the number of re-exploration for bleeding nor the number of patients needing blood products postoperatively was significantly increased in one group even though the placement of the device peristernally could have theoretically more often injured the remaining IMA. Second, pulmonary complications such as a pneumothorax, typically on the right side, as the pleura remains closed for most procedures, were again similar in both groups. Almost identical ICU and overall hospital lengths of stay confirm that patients of both groups did have similar postoperative clinical courses. We could therefore introduce the use of this newly developed device at our institution without increasing the risk of device-related complications when compared with the literature [14, 18]. Concerning the length of stay after sternal infection diagnosis, further information (such as the number of reoperation for instance for the vacuum-assisted therapy, the secondary closing technique, etc.) is needed to analyse the economical implication, which was beyond the scope of our study, but several other groups had already underlined the major impact of sternal wound infections on the economical outcome for hospitals [19] and for the whole care system decades before the introduction of new hospital financing systems [20, 21] such as the diagnosis-related groups policy in several countries [22].

Although perfusion and clamping time corresponded closely between both groups, the overall operation time was longer in the CW group by more than 10 min, confirming a faster closing technique as postulated in our first work [9]. Indeed, we hypothesized that the time before the CPB is the same in both groups since no differences were observed either in the types of procedures or in the number of patients operated off-pump in both groups. The difference in total operation time is therefore presumably between the end of the CPB and the skin suture. If more time had been spent in homeostasis in one or the other groups, this would have been reflected in the reoperation rate for bleeding or in the number of blood products given on the ICU, which is not the case, as already discussed above. We can therefore assume that the cable-tie-based sternal device allows a non-negligible time saving towards the end of the intervention.

LIMITATIONS

A first limitation lies in the nature of the retrospective study design. Although we have shown non-inferiority of ZF compared with CW in terms of safety issues, the low number of ZF patients hampered the desired proof of generating potentially higher mechanical stability with reduction of secondary infection. The use of the device at the discretion of the surgeons is a second limitation. At the same time, a personal learning curve could have been taken into consideration, particularly in order to better appreciate the postulated time gain [23]. A randomized controlled trial should now be started, preferably multicentric, in order to confirm these results by reducing potential selection bias. Third, the follow-up on infections, was at the time of gathering the data, not yet completed for all patients for 1 year, but for a minimum of 6 months.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study underlines the safety of the sternal ZF system in a cohort of patients undergoing cardiac surgery with regard to sternal infections. Sternal closure with this biocompatible PEEK cable-tie-based closure device is fast, easy to use, reliable and safe.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all members of the clinics for Cardiac Surgery at our institution for their great work and their accurate documentation as well as Andreas Widmer from the division for infectious diseases and hospital epidemiology for his insights and support.

REFERENCES

APPENDIX. CONFERENCE DISCUSSION

Dr T. Elenbaas(Eindhoven, Netherlands): I am also trying to prove the benefit of this new cable-based system, and I know how difficult it is to provide solid scientific evidence about this subject. Because you showed us the data as they came out, and I agree that it shows a relatively high percentage of sternal wound complications. But let us be honest, in every institution we see fluctuations in these complications from time to time.

I noticed in the patient characteristics that you have a relatively high number of patients having aortic surgery where you used deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, about 12%, which I think is relatively high, do you think that this subgroup is to be considered as a high-risk group?

Dr Melly: If I can answer now? No, it is not. We do a lot of circulatory arrest in deep hypothermia for a total or partial aortic root replacement. About 1/8th of our patients received this procedure, and we did not see any increase in the infection rate in that subgroup. Of course, the subgroup is too small, but there is no difference between the treatment groups. It was just to show the complexity of operations.

Dr Elenbaas: And the second question is, if I look at your standard steel wire technique, which consists of five figure-of-eight wires, which I think is a very good way of closing because it is more or less similar to ten single wires and, as we all know, extra wires, especially in the distal part, will provide better stability. Do you think you could show the difference between those groups better if you were to move to a more high-risk group of patients?

Dr Melly: Probably you are right. The thing is we do not want to change our standards, and most of our surgeons close the sternum with that figure-of-eight shape wiring with five USP 7 steel wires. The reason why we did that study is because we had an increase in the infection rate, since we began to use that device. Many people in the hospital started to think that it was because of the device itself. So the purpose of that study was just to see if indeed the increased infection at that time in our institution was caused by the introduction of the device or whether it was related to some other factors.

Dr Elenbaas: And just one last remark to encourage you with this system, we have so far implanted 160 patients in a more or less normal population and we have had only one patient with a mediastinitis but also a stable sternum. And from this 160, two patients with an instability where the sternum was not opened in the midline and was not well closed.

So we all know even with this system you can have technical problems, but as far as our study goes, we are so far enthusiastic. And we agree with you, the solution would be a multicentre prospective study.

Dr Melly: Just to add one comment on that, we had four patients that we had to resuscitate mechanically, and the four patients who had ZipFix did not need rewiring or refixation of the sternum. It remains stable for those patients.

Dr R. Deac(Targu-Mures, Romania): Did you mention anything about the cost?

Dr Melly: The cost at our institution at the moment is five to eight times more than conventional wires. We think that the more we use it, the greater the decrease will be in the price. But, of course, it was beyond the scope of the study to assess the real cost. But probably there are two factors. First, if you can reduce the primary instability that would lead to a secondary infection, then you would gain something. Second, if you can prove that you indeed gain on the operation time, it is ten minutes that do cost something to the institution also.

Dr A. Moritz(Frankfurt, Germany): Did I get it right that the ratchet you are using to finally close the band and cut, bears a load of 200 Newtons?

Dr Melly: Yes.

Dr Moritz: So with five of these straps, you create one ton of pretension load on the sternum. Do you know why this is necessary? One ton, that is quite a lot of load.

Dr Melly: I showed the physiological coughing.

Dr Moritz: Yes, I know, that is different. You get up to one and a half tons of load when you are coughing. That is correct. But you are pretensioning or pre-pressing the sternum by one ton.

Dr Melly: No. It is still 200 Newtons because it…

Dr Moritz: Yes, for one. If you have five?

Dr Melly: They are not in series. They are in parallel.

Dr Moritz: Yes. The total load on the sternum is one ton, the total: 5 times 200 is 1 ton.

Dr Melly: Well, it is not five times.

Dr Moritz: It is not on one point, I agree. But the total sternum load that you show during an aggressive cough is 1.5 tons on the whole sternum, correct?

Dr Melly: Yes, that is an aggressive cough, but that is not the…

Dr Moritz: One is tension and one is pressure. So I still do not understand why this high a pressure is necessary to adapt the sternum.

Dr Melly: as I said, this is given by the company. You cannot choose the 200 Newtons. This has been tested.

Dr Moritz: This is my question. Do you know why this is necessary?

Dr Melly: they have been testing that in different models. I just showed one, the dynamic loading. But there are some others, such as fatigue strength and some static loading that showed the load that you need to resist. You know, the one million cycles is the six weeks that you would need for the sternum to build bone and to be stable again. So I cannot change what the company decided.

Dr S. Borovic(Belgrade, Serbia): I have one question. We are talking about physics, stability. I am interested in another thing. How do the patients react? Do they have any complaints? Do they feel something strange with those bands, plastic and knots in comparison to the usual twisting wires?

Dr Melly: No. They really like the idea of the new device.

Dr Borovic: Especially cachectic or with less subcutaneous fat?

Dr Melly: That is what I mentioned in my presentation. I mean, for people who are cachectic or where you do not have any or much subcutaneous tissue, we do not use it because the locking head is a bit wider and higher than normal wiring. But the patient likes the idea. Up to now, we have not had any patients in whom we had to remove the device because of discomfort.

Mr J. ten Hoeve(Groningen, Netherlands): I have a practical question. The device, the tie rips I call them, are not radiolucent. Is that a problem for reoperations? For example, the patient is operated in your hospital, and is on vacation and has to have a resternotomy in another hospital, and it is not radiolucent. And the other problem can be if you remove those devices, you might lose pieces of it, and you cannot recover them. Is this a problem?

Dr Melly: To remove it in case of emergency, it is really easy. You take a big scissor and you cut them, so this is good. You cannot reuse them afterwards because you have to cut them. It is like a cable tie you use behind your TV at home, so you cannot reuse them either.

Mr ten Hoeve: Okay. But you have had no problems with other surgeons who had to perform a resternotomy, and they expect to see metal on the X-ray, but they do not at this moment? You cannot see them on an X-ray?

Dr Melly: I will tell you maybe in five or ten years when we have seen some of them, but this device was only introduced in 2010, so we have not had the opportunity to see how they might look after five years. But we describe in our operation protocol how many there are, and they are always in the intercostal space, so it is quite easy to find them.

Author notes

Presented at the 26th Annual Meeting of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Barcelona, Spain, 27–31 October 2012.

Comments

Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery

© The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. All rights reserved

The importance of sternal infection in postoperative infections is of course of great concern to all cardiac surgeons. As such this paper by Melly et al. [1] is both likely to be read with interest by many. Their primary objectives here were to determine the difference in sternal infection and other infectious events between conventional wire and cable-tie-based closure techniques post-sternotomy.

We do of course have to comment on the study limitations; they were limited by sample size, particularly their ZipFix™ cohort and is somewhat confounded by its retrospective design. There is further concern over the generalizability over the devices chosen, as the authors themselves state surgeons discretion in this area was a potential limiting factor.

A further randomized trial would be of immense clinical importance and interest and should of course be encouraged.

We thank Melly et al. for this insightful and interesting paper, on a universally important topic.

Reference

[1] Melly L, Gahl B, Meinke R, Rueter F, Matt P, Reuthebuch O et al. A new cable-tie-based sternal closure device: infectious considerations. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg 2013;17:219-224.

Conflict of interest:

none declared