-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mbakise Pula Matebele, Paul Peters, Julie Mundy, Pallav Shah, Cardiac tumors in adults: surgical management and follow-up of 19 patients in an Australian tertiary hospital, Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 10, Issue 6, June 2010, Pages 892–895, https://doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2009.230029

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The objective of this report is to share our experience with the different types of cardiac tumors, surgical management, postoperative complications and mid-term outcome of patients in an Australian tertiary hospital. Nineteen patients underwent cardiac surgery for tumors between 2001 and 2008. Their data was prospectively collected and retrospectively analyzed. The mean follow-up was 17 months. The follow-up was 100% through telephone interviews. There were multiple presenting symptoms with shortness of breath (7/19) as the most common. The tumors were atrial myxoma (14/19), fibroelastoma (2/19), angiosarcoma (1/19) and intravascular leiomyomatosis (1/19). A calcified thrombus (1/19) was misdiagnosed as a tumor. The fibroelastomas were shaved preserving valvular function. The angiosarcoma was incompletely resected with palliation intent. The leiomyomatosis and atrial myxoma were completely resected with satisfactory outcome. There was no in-hospital mortality. All patients were alive and were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I, except for the patient with a high-grade angiosarcoma who died eight months postoperatively. There was no evidence of recurrence in follow-up echocardiograms. Our experience and outcome is consistent with current literature. Atrial myxoma is the most common cardiac tumor and is curable with complete surgical resection. Fibroelastomas can be shaved off with low-risk of recurrence. Surgical management of angiosarcoma is palliative.

1. Introduction

Primary tumors of the heart are uncommon but not rare. The incidence of primary cardiac neoplasm ranges between 0.017% and 0.19% in various autopsy series [1, 2]. The variety of cardiac tumors range from non-neoplastic lesions to high-grade malignancies which occur over a wide range of ages. The most common tumor is atrial myxoma, which is reported to account for about 40%–90% of all primary cardiac tumors [3]. This is a retrospective study which aims to describe our experience with the different types of cardiac tumors, their modes of presentations, surgical management, complications and short-term follow-up results in an Australian tertiary hospital.

2. Materials and methods

The data on 19 patients operated between January 2001 and December 2008 was prospectively collected in a systematized database and retrospectively analyzed. This institution only treats adult patients. The mean age of the patients was 62 years (age range 28–82 years) and 58% were male (males 11; females 8).

We reviewed their presenting symptoms, modality of diagnosis, location of lesions, approach to surgery and surgical outcome through medical records, operative notes, pathology reports and echocardiogram. Patients underwent clinic follow-up and telephone interviews to confirm their current functional status. The consent was conducted by telephone. The study was exempted from ethics application because it was categorized as a low-risk audit.

3. Surgical management

The operative approach for all cases was through a median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass.

Right atriotomy was used in 85% (12/14) of the patients with atrial myxomas. The other two cases with atrial myxomas were accessed through a biatrial approach because of suboptimal exposure from an initial right atrial attempt. The mitral valve and ventricular cavities were assessed for multiple myxomas. The myxomas were resected with full thickness excision of the septum with 0.5–1 cm margin around the stalk. The repair was done with primary suturing in 9/14 cases whilst the rest were either reconstructed using autologous pericardium (4/14) or bovine pericardium (1/14).

Two patients had papillary fibroelastomas. One was attached to the non-coronary cusp of the aortic valve and the other one to the anterior papillary muscle of the mitral valve. They were both accessed through a transverse aortotomy and were shaved off without causing damage to underlying structures.

In the case involving an angiosarcoma, the venous cannulation involved the innominate vein and inferior vena cava. The tumor was approached via a right atriotomy and it was found attached to the superior part of the right atrial septum. It extended down through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle and up into the superior vena cava causing obstruction. The atrial septum was excised superiorly to leave a small cuff of tissue adjacent to the mitral annulus and aorta with further excision of some of the roof of the left atrium as well as the free right atrial wall. This excision was extended over to the superior vena cava. Most of the macroscopic tumor was excised, though there was some doubt of the margin over the mitral valve. Tumour extension across the tricuspid valve was removed piecemeal without damage to the valve or right ventricle. The atrial septum and the free right atrial wall between the superior vena cava and aorta were reconstructed with bovine pericardium as two separate pieces.

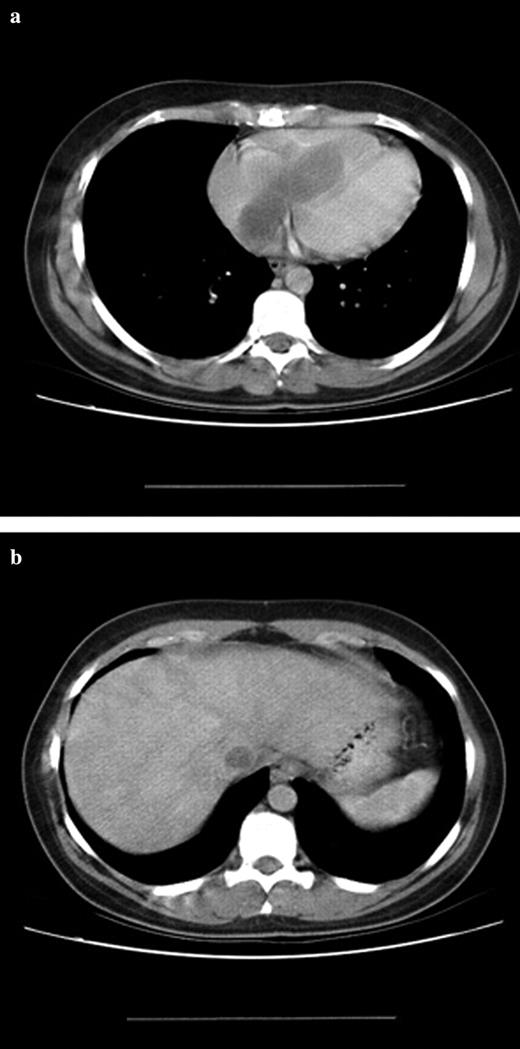

The intravascular leiomyomatosis originated in the uterus, extended through the right common iliac vein into the inferior vena cava all the way into the right atrium (Fig. 1a,b ). The patient had a combined surgical team involving cardiothoracic, vascular and gynecology. Through a right atriotomy, the tumor was excised from the right atrium and the proximal inferior vena cava. Whilst on bypass, the vascular surgeon excised the rest of the tumor involving the inferior vena cava and the right common iliac vein. The gynecologist performed a total hysterectomy after separation from the bypass and protamine administration.

(a) CT-scan of a leiomyomatosis in the right atrium. (b) CT-scan of a leiomyomatosis in the inferior vena cava.

4. Results

Nineteen patients underwent surgical resection for cardiac tumors. The most common tumor was atrial myxoma (14/19). The other tumors found in the study included fibroelastoma (2/19), intravascular leiomyomatosis (1/19) and angiosarcoma (1/19). A calcified thrombus (1/19) which was preoperatively misdiagnosed as a tumor was found attached to the septum in right atrium. This case has been included in the count of the tumors because it is a differential diagnoses (see Table 1 ). All atrial myxoma were left-sided. The different locations of the myxomas in the left atrium are shown in Table 2 . The patients had a wide range of symptoms/complaints (Table 3 ).

| Tumour type | Location | Size (cm×cm) | Number of |

| patients | |||

| Atrial myxoma | Left atrium | 1.5×2.0–7.5×6.5 | 14 |

| Fibroelastoma | Left ventricle+aortic valve | 0.3×0.3–1.5×0.8 | 2 |

| Calcified thrombus | Left atrium | 0.5×0.5 | 1 |

| High grade angiosarcoma | Right atrium | 10×10 | 1 |

| Intravascular leiomyomatosis | Right atrium | 10×3.5 | 1 |

| Tumour type | Location | Size (cm×cm) | Number of |

| patients | |||

| Atrial myxoma | Left atrium | 1.5×2.0–7.5×6.5 | 14 |

| Fibroelastoma | Left ventricle+aortic valve | 0.3×0.3–1.5×0.8 | 2 |

| Calcified thrombus | Left atrium | 0.5×0.5 | 1 |

| High grade angiosarcoma | Right atrium | 10×10 | 1 |

| Intravascular leiomyomatosis | Right atrium | 10×3.5 | 1 |

| Tumour type | Location | Size (cm×cm) | Number of |

| patients | |||

| Atrial myxoma | Left atrium | 1.5×2.0–7.5×6.5 | 14 |

| Fibroelastoma | Left ventricle+aortic valve | 0.3×0.3–1.5×0.8 | 2 |

| Calcified thrombus | Left atrium | 0.5×0.5 | 1 |

| High grade angiosarcoma | Right atrium | 10×10 | 1 |

| Intravascular leiomyomatosis | Right atrium | 10×3.5 | 1 |

| Tumour type | Location | Size (cm×cm) | Number of |

| patients | |||

| Atrial myxoma | Left atrium | 1.5×2.0–7.5×6.5 | 14 |

| Fibroelastoma | Left ventricle+aortic valve | 0.3×0.3–1.5×0.8 | 2 |

| Calcified thrombus | Left atrium | 0.5×0.5 | 1 |

| High grade angiosarcoma | Right atrium | 10×10 | 1 |

| Intravascular leiomyomatosis | Right atrium | 10×3.5 | 1 |

| Location | Number |

| Fossa ovalis/interatrial wall | 11 |

| Posterior mitral leaflet | 1 |

| Right infra lateral atrial wall | 1 |

| Roof of left atrium | 1 |

| Location | Number |

| Fossa ovalis/interatrial wall | 11 |

| Posterior mitral leaflet | 1 |

| Right infra lateral atrial wall | 1 |

| Roof of left atrium | 1 |

| Location | Number |

| Fossa ovalis/interatrial wall | 11 |

| Posterior mitral leaflet | 1 |

| Right infra lateral atrial wall | 1 |

| Roof of left atrium | 1 |

| Location | Number |

| Fossa ovalis/interatrial wall | 11 |

| Posterior mitral leaflet | 1 |

| Right infra lateral atrial wall | 1 |

| Roof of left atrium | 1 |

| Symptom | Number of |

| patients | |

| Incidental finding | 6 |

| Shortness of breath | 7 |

| Chest pain | 2 |

| Right heart failure | 1 |

| Left heart failure | 1 |

| Stroke | 4 |

| Syncope | 3 |

| Palpitations | 1 |

| Symptom | Number of |

| patients | |

| Incidental finding | 6 |

| Shortness of breath | 7 |

| Chest pain | 2 |

| Right heart failure | 1 |

| Left heart failure | 1 |

| Stroke | 4 |

| Syncope | 3 |

| Palpitations | 1 |

| Symptom | Number of |

| patients | |

| Incidental finding | 6 |

| Shortness of breath | 7 |

| Chest pain | 2 |

| Right heart failure | 1 |

| Left heart failure | 1 |

| Stroke | 4 |

| Syncope | 3 |

| Palpitations | 1 |

| Symptom | Number of |

| patients | |

| Incidental finding | 6 |

| Shortness of breath | 7 |

| Chest pain | 2 |

| Right heart failure | 1 |

| Left heart failure | 1 |

| Stroke | 4 |

| Syncope | 3 |

| Palpitations | 1 |

There was no in-hospital 30-day mortality. All the patients had an overnight ICU stay of <24 h. Arrhythmias were the most common morbidity. Atrial fibrillation and flutter were reported in 8/19 patients. The length of postoperative hospital stay ranged from four to 18 days (median 5 days). Hospital stay of a maximum of five days was achieved in 89% of patients. A 35-year-old patient with an atrial myxoma had a permanent pacemaker inserted for atrial flutter and complete heart block postoperatively. He stayed in hospital for a total of 15 days. A 54-year-old male with a myxoma who had suffered a preoperative stroke stayed in hospital for eight days postoperatively whilst awaiting inpatient rehabilitation.

The mean follow-up of the study was 17 months. All the patients except for one had a cardiothoracic outpatient review at six weeks and a cardiology outpatient follow-up at 12 weeks. In total 18/19 patients underwent a telephone interview recently and were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) I class. They all had a transthoracic echocardiogram at one year following surgery with no evidence of tumor recurrence. The only exception was the patient who had angiosarcoma, who then went back to New Zealand during the follow-up. That patient had marked symptomatic relief postoperatively and also had chemotherapy but died eight months later succumbing to the disease.

5. Discussion

In our study, benign primary cardiac tumors accounted for 89% (16/19) with left atrial myxoma being the most common for 74% (14/19) of the cases. Right-sided atrial myxoma have been reported in multiple case studies and account for ∼25% of cases [4] and biatrial myxoma have been reported in ∼2.5% of cases [4–6]. Myxomas are routinely found incidentally, or may present with embolic symptoms to the brain and limbs or with symptoms similar to mitral stenosis due to obstruction of flow across the mitral valve [7]. In our series, shortness of breath was the most common symptom followed by incidental findings during a routine work-up. Cerebrovascular accidents were reported in 3/14 of patients with atrial myxoma. The treatment option for atrial myxomas is surgical resection with curative intent. The controversy as to what margin of the septum should be excised to be considered safe remains. In our practice, we allow a 0.5-cm margin around the stalk and always do full thickness excision of the septum. The partial thickness excision technique has not been reported to be associated with increased recurrence [8]. Depending on the size, the defect may be primarily closed with a suture or patched with either an autologous or bovine pericardium as we did.

We have reported two cases of fibroelastomas (10%). Other series have reported a finding in the order of 0.9% [6]. These tumors arise characteristically from the cardiac valves or adjacent endocardium. The atrioventricular and semilunar valves are reported to be affected with equal frequency and if they involve the cardiac valve, they should be resected because of their known tendency to produce life-threatening complications [7]. Even though it was previously thought that they were innocuous findings during autopsies [7], it is now known that they are capable of producing obstruction of flow, particularly coronary ostial flow, and may embolize to the brain [8, 9]. In our series, one patient presented with a neurological event whilst the other presented with features of myocardial ischemia. The resection of these slow growing tumors is inarguable in view of these life-threatening complications. Valve repair rather than replacement should follow the resection whenever technically feasible, using conservative margins of resection [10]. We performed successful valve repair in both our patients.

The only single case of a malignant cardiac tumor in our experience was a high-grade angiosarcoma. The patient presented with syncopal episodes due to superior vena cava obstruction. Sarcomas are reported to account for 95% of malignant cardiac tumors [11]. These tumors display a wide variety of morphologies owing to their mesenchymal origin and their clinical course is usually rapidly progressive with death occurring as a result of wide spread metastasis. The varieties are angiosarcoma, rhadomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma.

Echocardiography is now the principle method for the diagnosis of cardiac tumors and for follow-up. It has the best spatial and temporal resolution of the cardiac imaging modalities, providing excellent anatomic and functional information [12]. It is sufficient to provide enough information to diagnose an intracardiac lesion, however, it cannot be used accurately to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions. In our practice, we use transesophageal echocardiogram perioperatively. Thrombus may mimic tumors, therefore, it is imperative to do a transesophageal echocardiogram during induction in case the thrombus has mobilized. We have had a case of a patient who had a left atrial mass incidentally found on a CT of the chest. This was confirmed by a transthoracic echocardiogram as a polypoid left atrial lesion resembling a myxoma. A month later, a perioperative transesophageal echocardiogram did not demonstrate an intracardiac lesion during induction and the surgery was cancelled. This saved the patient an unwarranted surgery. The patient was referred to the vascular medicine discipline for further investigation of thrombotic syndromes.

Other modalities, such as MRI and CT are being used and are particularly useful to detect primary and secondary cardiac malignant tumors. They can detect tumors 0.5–1 cm in size. They are particularly helpful in staging these lesions; to assess mural infiltration, to detect pericardial involvement, to determine tumor extension and to uncover metastatic disease [13]. Other authors argue the superiority of the use of contrast enhanced dynamic MRI for evaluation of cardiac tumors to gain further information about vascularization of tumor tissue. This is used to differentiate between tumors and thrombi.

The need for coronary angiography is mainly needed to exclude coronary artery disease in adult patients. Coronary angiograms were performed in 16/19 of our patients. They were omitted in two patients who were both 28 years of age and had no risk factors or complaints suggestive of coronary heart disease and in the patient with angiosarcoma who presented as an emergency.

The role of cardiac transplantation for cardiac tumors remains controversial. It may be considered for patients with malignant cardiac tumors without metastasis or unresectable benign tumors.

Even though we did not experience any 30-day in-hospital mortality, other series have reported figures ranging between 3% and 8.2% [14, 15] for myxoma patients. These deaths were in high-risk operative patients associated with late presentations and concomitant coronary artery or valvular heart disease.

Our study sample was very small and could have been improved by collaborating with other Australian institutions. Our results are consistent with current literature in regards to the incidence and postoperative outcome of cardiac tumors. Complete surgical resection of myxoma and shaving off of the fibroelastoma is the treatment of choice with low morbidity, mortality and recurrence rate. Surgical management of angiosarcoma is associated with good local control and palliation but with very poor prognosis. Complete excision of an intravascular leiomyomatosis has good outcome.

Presented at the 57th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, Sydney, Australia, August 13–16, 2009.

We acknowledge the assistance of John Fraser of the Prince Charles Critical Research Group and Fiona Canavan for proof reading of the manuscript.

References

- hemangiosarcoma

- heart neoplasms

- echocardiography

- cardiac surgery procedures

- atrial myxoma

- dyspnea

- postoperative complications

- adult

- follow-up

- hospital mortality

- leiomyomatosis

- surgical procedures, operative

- telephone

- heart

- neoplasms

- palliative care

- thrombus

- misdiagnosis

- excision

- new york heart association classification