-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Melissa Chan, Moses Fung, Kevin Chin Koon Siw, Reena Khanna, Anthony de Buck van Overstraeten, Elham Sabri, Jeffrey D McCurdy, Examination Under Anesthesia May Not Be Universally Required Prior to Anti-TNF Therapy in Perianal Crohn’s Disease: A Comparative Cohort Study, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 29, Issue 5, May 2023, Pages 763–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac143

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Multidisciplinary care involving exam under anesthesia (EUA) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors is recommended for perianal Crohn’s disease. However, the impact of this combined approach is not well established.

We performed a comparative cohort study between 2009 and 2019. Patients with perianal Crohn’s disease treated with EUA before anti-TNF therapy (combined modality therapy) were compared with anti-TNF alone. The primary outcome was fistula closure assessed clinically. Secondary outcomes included subsequent local surgery and fecal diversion. Multivariable analysis adjusted for abscesses, concomitant immunomodulators, and time to anti-TNF initiation was performed.

Anti-TNF treatment was initiated 188 times in 155 distinct patients: 66 (35%) after EUA. Abscesses (50% vs 15%; P < .001) and concomitant immunomodulators (64% vs 50%; P = .07) were more common in the combined modality group, while age, smoking status, disease duration, and intestinal disease location were not significantly different. Combined modality therapy was not associated with higher rates of fistula closure at 3 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.3-1.8), 6 (aOR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4-2.0) and 12 (aOR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.4-2.2) months. After a median follow-up of 4.6 (interquartile range, 5.95; 2.23-8.18) years, combined therapy was associated with subsequent local surgical intervention (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.6) but not with fecal diversion (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.45-3.9). Results remained consistent when excluding patients with abscesses and prior biologic failure.

EUA before anti-TNF therapy was not associated with improved clinical outcomes compared with anti-TNF therapy alone, suggesting that EUA may not be universally required. Future prospective studies controlling for fistula severity are warranted.

Lay Summary

This comparative cohort study found that an exam under anesthesia before initiation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in perianal Crohn’s disease was not associated with higher rates of fistula closure, suggesting that an exam under anesthesia may not be universally required in patients with perianal Crohn’s disease.

Current guidelines recommend a combined approach of an exam under anesthesia and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy for treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease.

This is the largest retrospective study to date showing that perianal Crohn’s disease patients who underwent an exam under anesthesia prior to anti-TNF therapy did not have improved clinical outcomes compared with those who underwent anti-TNF therapy alone.

Patients presenting with perianal Crohn’s disease may not universally require an exam under anesthesia prior to biologic therapy.

Introduction

Perianal fistulizing disease is one of the most common and difficult to treat phenotypes of Crohn’s disease. Historically, it has been reported in up to 30% of patients with luminal Crohn’s disease,1-4 although recent studies suggest that the rates may be declining, potentially owing to advances in medical therapy.5 It often follows a relapsing remitting course that can result in frequent episodes of fistula drainage and recurrent episodes of perianal pain, particularly when abscesses are present.6,7 This has far reaching impacts on physical, psychological, and psychosocial health.8-12

International guidelines recommend a multidisciplinary approach for treatment, with an emphasis on fistula drainage by an exam under anesthesia (EUA) followed by medical treatment with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor.13-15 An EUA allows for drainage of abscess and fluid-filled tracts, along with insertion of loose-fitting setons to prevent abscess recurrence. This strategy not only is believed to be an important component of the initial management of perianal Crohn’s disease, but also may augment the effectiveness of anti-TNF therapy.16 The latter is particularly important because only a minority of patients achieve long-term healing of perianal fistulas. In a meta-analysis of 6 controlled studies assessing the efficacy of anti-TNF therapy, as few as 34% of patients who initially responded to therapy maintained long-term healing.16

Recommendations for a combined medical–surgical approach for management of perianal fistulas are based largely on expert opinion. To date, only 4 studies, with conflicting findings, directly compared an EUA–anti-TNF treatment approach with anti-TNF treatment alone.17-20 These studies contained small sample sizes and did not control for potential confounding variables, which prevents strong conclusions from being drawn from this work. As a result, the overarching aim of our study was to compare the effectiveness of a combined EUA–anti-TNF treatment approach with anti-TNF therapy alone for perianal Crohn’s disease. We hypothesized that EUA before anti-TNF therapy would improve fistula closure and prevent the requirement for subsequent surgical intervention compared with anti-TNF therapy alone.

Methods

Study Design and Cohort Generation

We performed a retrospective observational study between January 2009 and December 2019 using data from the Ottawa Hospital, one of the largest tertiary care centers in Canada, with a catchment area that serves approximately 12 000 patients with IBD. Our hospital network consists of 3 campuses with 1200 inpatient beds and 60 000 admissions per year.

Patients were identified by a search of our institutional discharge records database using International Statistical Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision coding: K50* for Crohn’s disease, K51*, along with codes associated with perianal fistulas, including K60.3, and the Canadian Classification of Health Intervention procedural codes for EUA. A manual chart review was conducted to confirm the diagnosis of perianal Crohn’s disease and to assess study eligibility. We included adults (>17 years of age) with complex perianal fistulas, defined according to established criteria by the American Gastroenterological Association,21 who received at least 3 induction doses of anti-TNF therapy (infliximab, adalimumab, or golimumab) for active perianal Crohn’s disease. We excluded patients with perianal fistulas related to alternate identifiable causes, patients with an ileal pouch–anal anastomosis or a diverting ostomy, patients who initiated anti-TNF therapy without active perianal disease, and patients with inadequate records to determine clinical outcomes.

Outcomes and Definitions

Eligible patients were stratified into 2 groups: EUA before anti-TNF therapy for patients who underwent an EUA within 1 year of initiating anti-TNF therapy and anti-TNF therapy alone. The decision to perform an EUA was left to the discretion of the treating gastroenterologist and surgeon. Patients who were treated with more than 1 anti-TNF therapy were counted as separate encounters for each anti-TNF therapy. The presence of an abscess was determined by pelvic magnetic resonance imaging studies, defined as a fluid collection >2 cm, and by reviewing surgical reports or clinical records.

The primary outcome was fistula closure, defined clinically as an absence of spontaneous drainage, and, if performed, an absence of exudate by finger compression test. Secondary outcomes included requirement for a subsequent local surgical intervention and requirement for fecal diversion. Local surgical interventions were defined as any of the following: incision and drainage, EUA, fistulotomy, advancement flap, ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract, or fistula plug or glue.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, comorbidities, and medication exposure. Categorical variables were presented as proportions and continuous variables as mean ± SD for normally distributed data or median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data.

The rates of fistula closure were compared between groups at 3, 6, and 12 months by univariable logistic regression and summarized as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Multivariable logistic regression was performed to control for potential confounding variables (abscesses, concomitant immunomodulators, and time to anti-TNF start). These variables were selected a priori based on literature review and consensus among authors. Time-to-event analyses were assessed using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared between groups by Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for abscesses, concomitant immunomodulators, and time to anti-TNF start.

To explore for potential sources of heterogeneity, we performed multiple subgroup analyses based on (1) prior anti-TNF therapy exposure (naïve vs experienced) and (2) anti-TNF type (infliximab vs adalimumab). As an initial measure to control for fistula severity, we performed a sensitivity analysis that included only patients without an abscess. To account for potentially changes in fistula anatomy or severity over time, a sensitivity analysis was performed assessing the impact of time since EUA (>4 months or <4 months) on fistula healing. Finally, to assess for the potential impact of setons, we compared patients who had a seton with those who did not.

For all analyses, significance was considered positive when P values were <.05.

Results

Patient Population

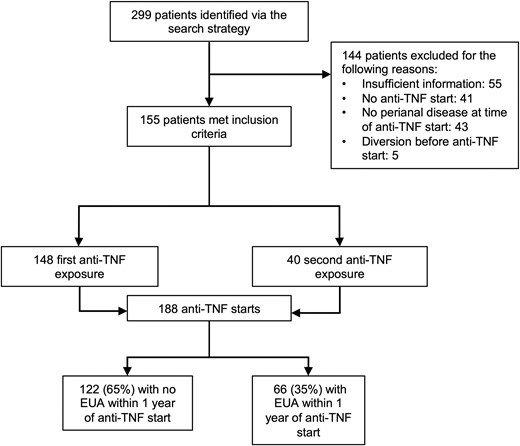

A total of 299 patients with perianal Crohn’s disease were treated in our center during the study period. A total of 155 (52%) patients met our study criteria. Reasons for exclusion are listed in Figure 1. Among these patients, there were a total of 188 distinct anti-TNF treatments inductions (Figure 1). Overall, 66 (35%) EUA procedures were performed prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy. The median time from EUA to anti-TNF therapy was 4 (interquartile range, 7.75) months.

Flow diagram of included and excluded cases. EUA, exam under anesthesia; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics are reported in Table 1. There were no differences in age, smoking status, disease duration, location of luminal disease, type of anti-TNF treatment, and use of concomitant antibiotics between cohorts. The mean duration of anti-TNF therapy was 4.9 ± 3.8 years for patients with an EUA and 5.6 ± 3.8 years for patients without an EUA. More patients had concomitant immunomodulators in the EUA + anti-TNF group, but this did not reach statistical significance (64% vs 50%; P = .07). There was a greater proportion of male patients (67% vs 46%; P = .007) and patients with an abscess (50% vs 15%; P < .001) who underwent an EUA prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy. The mean serum concentrations of infliximab (8.1 ± 5.9 mg/mL vs 5.1 ± 4.3 mg/mL; P = .23) and adalimumab (13.4 ± 7.6 µg/mL vs 10.8 ± 5.9 µg/mL; P = .36) were similar between patients with and without an EUA, respectively.

| . | No EUA (n = 122) . | EUA (n = 66) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 56 (45.9) | 44 (66.7) | .007 |

| Age, ya | 34.6 ± 13.6 | 34.9 ± 11.4 | .91 |

| Duration, mob | 47.2 ± 76.7 | 45.8 ± 56.8 | .90 |

| Smoking history | .10 | ||

| Yes | 54 (44.3) | 32 (48.5) | |

| No | 42 (34.4) | 28 (42.4) | |

| Unknown | 26 (21.3) | 6 (4.9) | |

| Intestinal location | .21 | ||

| Ileum (L1) | 37 (30.3) | 19 (28.8) | |

| Colonic (L2) | 43 (35.2) | 22 (33.3) | |

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 22 (18.0) | 15 (22.7) | |

| Isolated perianal disease | 7 (5.7) | 8 (12.1) | |

| Rectal inflammation | 58 (47.5) | 27 (40.9) | .38 |

| Fistula characteristics by MRI | |||

| Tractsc | <.001 | ||

| 1 | 35 (27.9) | 21 (31.8) | |

| 2 | 16 (13.1) | 20 (30.3) | |

| 3 or more | 5 (4.1) | 11 (16.7) | |

| Abscess | 18 (14.8) | 33 (50.0) | <.001 |

| Anti-TNF | .33 | ||

| Infliximab | 69 (56.6) | 40 (60.6) | |

| Adalimumab | 53 (43.4) | 25 (37.9) | |

| Golimumab | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Concomitant treatments | |||

| Antibiotics | 32 (26.2) | 18 (27.3) | .88 |

| Immunomodulators | 61 (50.0) | 42 (63.6) | .07 |

| . | No EUA (n = 122) . | EUA (n = 66) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 56 (45.9) | 44 (66.7) | .007 |

| Age, ya | 34.6 ± 13.6 | 34.9 ± 11.4 | .91 |

| Duration, mob | 47.2 ± 76.7 | 45.8 ± 56.8 | .90 |

| Smoking history | .10 | ||

| Yes | 54 (44.3) | 32 (48.5) | |

| No | 42 (34.4) | 28 (42.4) | |

| Unknown | 26 (21.3) | 6 (4.9) | |

| Intestinal location | .21 | ||

| Ileum (L1) | 37 (30.3) | 19 (28.8) | |

| Colonic (L2) | 43 (35.2) | 22 (33.3) | |

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 22 (18.0) | 15 (22.7) | |

| Isolated perianal disease | 7 (5.7) | 8 (12.1) | |

| Rectal inflammation | 58 (47.5) | 27 (40.9) | .38 |

| Fistula characteristics by MRI | |||

| Tractsc | <.001 | ||

| 1 | 35 (27.9) | 21 (31.8) | |

| 2 | 16 (13.1) | 20 (30.3) | |

| 3 or more | 5 (4.1) | 11 (16.7) | |

| Abscess | 18 (14.8) | 33 (50.0) | <.001 |

| Anti-TNF | .33 | ||

| Infliximab | 69 (56.6) | 40 (60.6) | |

| Adalimumab | 53 (43.4) | 25 (37.9) | |

| Golimumab | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Concomitant treatments | |||

| Antibiotics | 32 (26.2) | 18 (27.3) | .88 |

| Immunomodulators | 61 (50.0) | 42 (63.6) | .07 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: EUA, exam under anesthesia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

aAt diagnosis of perianal disease.

bFrom time of diagnosis to initiation of TNF inhibitor.

cAggregate number of primary and secondary fistula tracts.

| . | No EUA (n = 122) . | EUA (n = 66) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 56 (45.9) | 44 (66.7) | .007 |

| Age, ya | 34.6 ± 13.6 | 34.9 ± 11.4 | .91 |

| Duration, mob | 47.2 ± 76.7 | 45.8 ± 56.8 | .90 |

| Smoking history | .10 | ||

| Yes | 54 (44.3) | 32 (48.5) | |

| No | 42 (34.4) | 28 (42.4) | |

| Unknown | 26 (21.3) | 6 (4.9) | |

| Intestinal location | .21 | ||

| Ileum (L1) | 37 (30.3) | 19 (28.8) | |

| Colonic (L2) | 43 (35.2) | 22 (33.3) | |

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 22 (18.0) | 15 (22.7) | |

| Isolated perianal disease | 7 (5.7) | 8 (12.1) | |

| Rectal inflammation | 58 (47.5) | 27 (40.9) | .38 |

| Fistula characteristics by MRI | |||

| Tractsc | <.001 | ||

| 1 | 35 (27.9) | 21 (31.8) | |

| 2 | 16 (13.1) | 20 (30.3) | |

| 3 or more | 5 (4.1) | 11 (16.7) | |

| Abscess | 18 (14.8) | 33 (50.0) | <.001 |

| Anti-TNF | .33 | ||

| Infliximab | 69 (56.6) | 40 (60.6) | |

| Adalimumab | 53 (43.4) | 25 (37.9) | |

| Golimumab | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Concomitant treatments | |||

| Antibiotics | 32 (26.2) | 18 (27.3) | .88 |

| Immunomodulators | 61 (50.0) | 42 (63.6) | .07 |

| . | No EUA (n = 122) . | EUA (n = 66) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 56 (45.9) | 44 (66.7) | .007 |

| Age, ya | 34.6 ± 13.6 | 34.9 ± 11.4 | .91 |

| Duration, mob | 47.2 ± 76.7 | 45.8 ± 56.8 | .90 |

| Smoking history | .10 | ||

| Yes | 54 (44.3) | 32 (48.5) | |

| No | 42 (34.4) | 28 (42.4) | |

| Unknown | 26 (21.3) | 6 (4.9) | |

| Intestinal location | .21 | ||

| Ileum (L1) | 37 (30.3) | 19 (28.8) | |

| Colonic (L2) | 43 (35.2) | 22 (33.3) | |

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 22 (18.0) | 15 (22.7) | |

| Isolated perianal disease | 7 (5.7) | 8 (12.1) | |

| Rectal inflammation | 58 (47.5) | 27 (40.9) | .38 |

| Fistula characteristics by MRI | |||

| Tractsc | <.001 | ||

| 1 | 35 (27.9) | 21 (31.8) | |

| 2 | 16 (13.1) | 20 (30.3) | |

| 3 or more | 5 (4.1) | 11 (16.7) | |

| Abscess | 18 (14.8) | 33 (50.0) | <.001 |

| Anti-TNF | .33 | ||

| Infliximab | 69 (56.6) | 40 (60.6) | |

| Adalimumab | 53 (43.4) | 25 (37.9) | |

| Golimumab | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Concomitant treatments | |||

| Antibiotics | 32 (26.2) | 18 (27.3) | .88 |

| Immunomodulators | 61 (50.0) | 42 (63.6) | .07 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: EUA, exam under anesthesia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

aAt diagnosis of perianal disease.

bFrom time of diagnosis to initiation of TNF inhibitor.

cAggregate number of primary and secondary fistula tracts.

Fistula Closure

Fistula closure occurred in 29% of patients at 3 months, 35% of patients at 6 months, and 39% of patients at 12 months. There were no significant differences in the rates of fistula closure, at each time point, between patients with and without an EUA prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy (Table 2). After adjusting for abscesses, exposure to immunomodulators, and time to anti-TNF start, there were no significant differences between cohorts in the rates of fistula closure (Table 3). The results remained unchanged when limiting the analysis to patients who did not have an abscess prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy and patients treated with their first anti-TNF therapy (Table 2). When patients were stratified by anti-TNF type, there were no major differences in fistula closure between cohorts (Supplementary Table 1). Finally, there were no differences between cohorts in fistula healing at 3 (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.3-1.8; P = .49), 6 (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.3-1.5; P = .33), and 12 (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.3-1.6; P = .61) months when EUA exposure was defined as an EUA performed within 4 months of initiating anti-TNF therapy (Table 2).

Rates of Fistula Closure After Anti-TNF Therapy Comparing Patients With and Without an EUA

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure at 3 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 40/122 (32.8) | 15/66 (22.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | .15 |

| First anti-TNFb | 25/92 (27.2) | 13/56 (23.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.8) | .59 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0.3 (0.1-1.4) | .11 |

| No abscessd | 15/40 (37.5) | 6/22 (27.3) | 0.6 (0.2-2.0) | .42 |

| Recent EUAe | 47/155 (30.3) | 8/33 (24.2) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .49 |

| Fistula closure at 6 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 45/122 (36.9) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | .37 |

| First anti-TNFb | 30/92 (32.6) | 17/56 (30.6) | 0.9 (0.4-1.9) | .78 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 3/10 (30.0) | 0.4 (0.1-2.0) | .28 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 8/22 (36.4) | 0.6 (0.2-1.8) | .40 |

| Recent EUAe | 56/155 (36.1) | 9/33 (27.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.5) | .33 |

| Fistula closure at 12 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 50/122 (41.0) | 24/66 (36.4) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .54 |

| First anti-TNFb | 36/92 (39.1) | 20/56 (36.4) | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | .68 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 14/30 (46.6) | 4/10 (40.0) | 0.8 (0.2-3.3) | .71 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 9/22 (40.1) | 0.8 (0.3-2.2) | .62 |

| Recent EUAe | 63/155 (40.6) | 11/33 (33.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | .61 |

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure at 3 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 40/122 (32.8) | 15/66 (22.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | .15 |

| First anti-TNFb | 25/92 (27.2) | 13/56 (23.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.8) | .59 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0.3 (0.1-1.4) | .11 |

| No abscessd | 15/40 (37.5) | 6/22 (27.3) | 0.6 (0.2-2.0) | .42 |

| Recent EUAe | 47/155 (30.3) | 8/33 (24.2) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .49 |

| Fistula closure at 6 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 45/122 (36.9) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | .37 |

| First anti-TNFb | 30/92 (32.6) | 17/56 (30.6) | 0.9 (0.4-1.9) | .78 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 3/10 (30.0) | 0.4 (0.1-2.0) | .28 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 8/22 (36.4) | 0.6 (0.2-1.8) | .40 |

| Recent EUAe | 56/155 (36.1) | 9/33 (27.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.5) | .33 |

| Fistula closure at 12 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 50/122 (41.0) | 24/66 (36.4) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .54 |

| First anti-TNFb | 36/92 (39.1) | 20/56 (36.4) | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | .68 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 14/30 (46.6) | 4/10 (40.0) | 0.8 (0.2-3.3) | .71 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 9/22 (40.1) | 0.8 (0.3-2.2) | .62 |

| Recent EUAe | 63/155 (40.6) | 11/33 (33.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | .61 |

Values are n/n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EUA, exam under anesthesia; OR, odds ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

aPerformed within 1 year before starting anti-TNF therapy.

bSensitivity analysis of patients treated with their first anti-TNF.

cSensitivity analysis of patients treated with their second anti-TNF.

dSensitivity analysis of patients who did not have an abscess clinically or radiographically.

eEUA performed within 4 months before starting anti-TNF therapy.

Rates of Fistula Closure After Anti-TNF Therapy Comparing Patients With and Without an EUA

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure at 3 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 40/122 (32.8) | 15/66 (22.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | .15 |

| First anti-TNFb | 25/92 (27.2) | 13/56 (23.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.8) | .59 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0.3 (0.1-1.4) | .11 |

| No abscessd | 15/40 (37.5) | 6/22 (27.3) | 0.6 (0.2-2.0) | .42 |

| Recent EUAe | 47/155 (30.3) | 8/33 (24.2) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .49 |

| Fistula closure at 6 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 45/122 (36.9) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | .37 |

| First anti-TNFb | 30/92 (32.6) | 17/56 (30.6) | 0.9 (0.4-1.9) | .78 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 3/10 (30.0) | 0.4 (0.1-2.0) | .28 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 8/22 (36.4) | 0.6 (0.2-1.8) | .40 |

| Recent EUAe | 56/155 (36.1) | 9/33 (27.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.5) | .33 |

| Fistula closure at 12 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 50/122 (41.0) | 24/66 (36.4) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .54 |

| First anti-TNFb | 36/92 (39.1) | 20/56 (36.4) | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | .68 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 14/30 (46.6) | 4/10 (40.0) | 0.8 (0.2-3.3) | .71 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 9/22 (40.1) | 0.8 (0.3-2.2) | .62 |

| Recent EUAe | 63/155 (40.6) | 11/33 (33.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | .61 |

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure at 3 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 40/122 (32.8) | 15/66 (22.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | .15 |

| First anti-TNFb | 25/92 (27.2) | 13/56 (23.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.8) | .59 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0.3 (0.1-1.4) | .11 |

| No abscessd | 15/40 (37.5) | 6/22 (27.3) | 0.6 (0.2-2.0) | .42 |

| Recent EUAe | 47/155 (30.3) | 8/33 (24.2) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .49 |

| Fistula closure at 6 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 45/122 (36.9) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | .37 |

| First anti-TNFb | 30/92 (32.6) | 17/56 (30.6) | 0.9 (0.4-1.9) | .78 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 15/30 (50.0) | 3/10 (30.0) | 0.4 (0.1-2.0) | .28 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 8/22 (36.4) | 0.6 (0.2-1.8) | .40 |

| Recent EUAe | 56/155 (36.1) | 9/33 (27.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.5) | .33 |

| Fistula closure at 12 mo | ||||

| Overall cohorta | 50/122 (41.0) | 24/66 (36.4) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .54 |

| First anti-TNFb | 36/92 (39.1) | 20/56 (36.4) | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | .68 |

| Second anti-TNFc | 14/30 (46.6) | 4/10 (40.0) | 0.8 (0.2-3.3) | .71 |

| No abscessd | 19/40 (47.5) | 9/22 (40.1) | 0.8 (0.3-2.2) | .62 |

| Recent EUAe | 63/155 (40.6) | 11/33 (33.3) | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | .61 |

Values are n/n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EUA, exam under anesthesia; OR, odds ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

aPerformed within 1 year before starting anti-TNF therapy.

bSensitivity analysis of patients treated with their first anti-TNF.

cSensitivity analysis of patients treated with their second anti-TNF.

dSensitivity analysis of patients who did not have an abscess clinically or radiographically.

eEUA performed within 4 months before starting anti-TNF therapy.

Rates of Fistula Closure Adjusted for Abscess, Exposure to Immunomodulator and Time to Anti-TNF Comparing Patients With and Without an EUA

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure | ||||

| 3 mo | 40/119 (33.6) | 15/65 (23.1) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .50 |

| 6 mo | 45/114 (39.5) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.8 (0.4-2.0) | .70 |

| 12 mo | 50/114 (43.9) | 24/63 (38.1) | 1.0 (0.4-2.2) | .92 |

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure | ||||

| 3 mo | 40/119 (33.6) | 15/65 (23.1) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .50 |

| 6 mo | 45/114 (39.5) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.8 (0.4-2.0) | .70 |

| 12 mo | 50/114 (43.9) | 24/63 (38.1) | 1.0 (0.4-2.2) | .92 |

Values are n/n (%), unless otherwise indicated. Analysis adjusted for abscess, number of fistula tracts, concomitant immunomodulator, sex and time to anti-TNF start.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EUA, exam under anesthesia; OR, odds ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Rates of Fistula Closure Adjusted for Abscess, Exposure to Immunomodulator and Time to Anti-TNF Comparing Patients With and Without an EUA

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure | ||||

| 3 mo | 40/119 (33.6) | 15/65 (23.1) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .50 |

| 6 mo | 45/114 (39.5) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.8 (0.4-2.0) | .70 |

| 12 mo | 50/114 (43.9) | 24/63 (38.1) | 1.0 (0.4-2.2) | .92 |

| . | No EUA . | EUA . | Adjusted OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fistula closure | ||||

| 3 mo | 40/119 (33.6) | 15/65 (23.1) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | .50 |

| 6 mo | 45/114 (39.5) | 20/66 (30.3) | 0.8 (0.4-2.0) | .70 |

| 12 mo | 50/114 (43.9) | 24/63 (38.1) | 1.0 (0.4-2.2) | .92 |

Values are n/n (%), unless otherwise indicated. Analysis adjusted for abscess, number of fistula tracts, concomitant immunomodulator, sex and time to anti-TNF start.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EUA, exam under anesthesia; OR, odds ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

A total of 47 anti-TNF inductions were performed in patients who had seton(s), and 141 anti-TNF inductions were performed in patients without setons (20 encounters who underwent an EUA and 121 encounters who did not undergo an EUA) (Table 4). Among patients with setons, the seton(s) remained present in 30 (64%) patients at 3 months, 29 (61%) patients at 6 months, and 27 (57%) patients at 12 months. Fewer patients who underwent seton insertion achieved fistula closure at 3 months (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2-1.0; P = .03) but not at 6 months (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4-1.5; P = .43) or 12 months (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4-1.5; P = .39). Among patients who underwent an EUA (47 with seton[s] and 19 without a seton), there were no significant differences in the rates of fistula closure (P > .05 for all time points) (Table 4).

Rates of Fistula Closure After Anti-TNF Therapy Comparing Patients With and Without a Seton

| . | Seton . | No Seton . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 47/141 (33.3) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) | .03 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 51/141 (36.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .43 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 58/141 (41.1) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .39 |

| Only patients who underwent an EUA | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.5 (0.2-1.7) | .28 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.9 (0.3-2.9) | .89 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 8/19 (42.1) | 0.7 (0.2-2.1) | .54 |

| . | Seton . | No Seton . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 47/141 (33.3) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) | .03 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 51/141 (36.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .43 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 58/141 (41.1) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .39 |

| Only patients who underwent an EUA | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.5 (0.2-1.7) | .28 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.9 (0.3-2.9) | .89 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 8/19 (42.1) | 0.7 (0.2-2.1) | .54 |

Values are n/n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EUA, exam under anesthesia; OR, odds ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor α.

Rates of Fistula Closure After Anti-TNF Therapy Comparing Patients With and Without a Seton

| . | Seton . | No Seton . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 47/141 (33.3) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) | .03 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 51/141 (36.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .43 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 58/141 (41.1) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .39 |

| Only patients who underwent an EUA | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.5 (0.2-1.7) | .28 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.9 (0.3-2.9) | .89 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 8/19 (42.1) | 0.7 (0.2-2.1) | .54 |

| . | Seton . | No Seton . | OR (95% CI) . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 47/141 (33.3) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) | .03 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 51/141 (36.2) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .43 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 58/141 (41.1) | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) | .39 |

| Only patients who underwent an EUA | ||||

| 3 mo | 9/47 (19.1) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.5 (0.2-1.7) | .28 |

| 6 mo | 14/47 (29.8) | 6/19 (31.6) | 0.9 (0.3-2.9) | .89 |

| 12 mo | 16/47 (34.0) | 8/19 (42.1) | 0.7 (0.2-2.1) | .54 |

Values are n/n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EUA, exam under anesthesia; OR, odds ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor α.

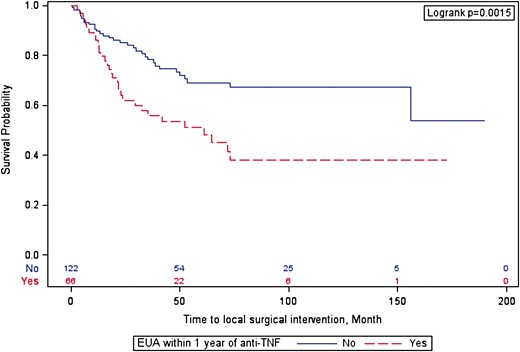

Requirement for Surgical Intervention

The median follow-up after initiating anti-TNF therapy was 4.58 (interquartile range, 5.94) years. There were no differences in the time to anti-TNF therapy discontinuation between cohorts (log-rank P = .35). Patients who underwent an EUA prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy were more likely to require a subsequent local surgery than patients who did not undergo an EUA (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.6) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The majority of local surgeries involved incision and drainage or EUA with or without seton placement (89%). Only 7 (11%) patients underwent a fistulotomy, and no patients underwent a ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract , advancement flap, or fistula plug or glue procedures (Supplementary Table 3). Similar findings occurred when limiting the analysis to patients who did not have an abscess prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy and patients who were treated with their first anti-TNF therapy (Supplementary Table 4).

Surgical intervention–free survival after initiating anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. EUA, exam under anesthesia.

A total of 34 (18%) patients underwent a fecal diversion surgery: 25 (74%) patients (7 patients with an EUA and 18 patients without an EUA) primarily to manage uncontrolled perianal disease and 9 (26%) patients (4 patients with an EUA and 5 patients without an EUA) primarily to manage uncontrolled luminal disease. There were no differences in the time to fecal diversion (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.45-3.9) between cohorts (Supplementary Table 2). Similar findings also occurred when limiting the analysis to patients who did not have an abscess prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy and patients who were treated with their first anti-TNF therapy (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

In this retrospective observational study, EUA prior to anti-TNF therapy was not associated with improved clinical outcomes compared with anti-TNF therapy alone. There was no difference in the rates of fistula closure or requirement for fecal diversion; however, patients who underwent an EUA prior to anti-TNF therapy were twice as likely to require subsequent local surgical intervention (EUA with or without setons). These findings remained unchanged in patients without an abscess and irrespective of the use of setons.

To date, only 4 comparative cohort studies have directly assessed the benefit of EUA prior to anti-TNF therapy compared with anti-TNF therapy alone.17-20 All studies were retrospective and contained a limited number of patients (15-32 patients per study). Although combined therapy was not significantly associated with clinical healing of fistula tracts in any of these studies, there were numerically higher rates of fistula healing in 3 of 4 studies.16 Furthermore, in the study by Regueiro and Mardini,17 patients who underwent an EUA prior to anti-TNF therapy were less likely to have recurrent fistula drainage (44% vs 79%; P = .001). In contrast to these studies, combined EUA and anti-TNF therapy compared with EUA alone is associated with significantly higher rates of fistula healing.22 Additionally, in the Multimodal treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: Seton versus anti-TNF versus advancement plasty (PISA) trial, a prospective randomized controlled trial that compared various treatment option for perianal Crohn’s disease, patients who were treated with combined EUA were less likely to require further surgical intervention (n = 6 [42%]) than patients treated with chronic setons alone (n = 10 [74%]).23

There are several potential explanations why the combined surgical and medical treatment approach did not universally improve fistula healing in the aforementioned studies. First, all studies were retrospective. Therefore, they had an inherent risk of confounding by indication, whereby patients with more severe fistulizing disease may have been more likely to undergo an EUA prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy. Second, these studies did not control for potential confounding variables. Although our study was the only dedicated comparative cohort study to control for confounding variables (abscesses, concomitant immunomodulators, and time to initiation of anti-TNF), we were not able to control for fistula severity. Finally, these studies were small, which may have resulted in type II error. It is also possible that in some clinical scenarios combined surgical and medical treatment does not improve fistula outcomes, as setons may impair long-term healing by promoting tract epithelization. In keeping with this hypothesis, reduced fistula healing was demonstrated when setons were left in situ for longer than 2 months.24 In our study, seton(s) remained present for over a year in more than half of the patients who underwent seton insertion. To date, no studies have evaluated the optimal timing of seton removal.

Several studies indirectly suggest a potential benefit of a combined treatment approach. A retrospective multicenter study from Europe and Israel found that multimodality therapy defined as medical treatments (biologics ± immunomodulators ± antibiotics) along with local surgical intervention (EUA ± seton drainage) resulted in higher rates of complete fistula healing (52% vs 42%; P = .04) and lower rates of repeat surgical intervention (25% vs 59%; P = .001) compared with single-modality therapy.25 However, this study did not specifically compare multimodality therapy with anti-TNF therapy alone. Similarly, a population-based study using administrative health data from the Truven Health MarketScan Database in the United States found that patients who had setons prior to treatment with biologics incurred lower healthcare costs and required fewer hospitalizations.26 However, this study was not able to assess fistula healing directly, nor did it use validated methods to identify perianal Crohn’s disease. Finally, the high rates of fistula healing in the control arm of the Adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells for induction of remission in perianal fistulizing Crohn's Disease (ADMIRE-I) clinical trial suggested that an EUA with meticulous curettage of the fistula tracts and ligation of the internal opening may improve fistula healing in patients treated with immunosuppressive therapies.27

Our study had several notable strengths. To our knowledge, it is the largest dataset formally comparing the combination of EUA and anti-TNF therapy with anti-TNF therapy alone. Additionally, of the studies that directly compared these treatment approaches, it is the only one that controlled for multiple confounding variables. Finally, in addition to assessing fistula closure, we also assessed the requirement for local surgical intervention and fecal diversion to obtain a more complete picture of the impact of multimodality therapy on fistula outcomes.

Our study also had a number of important limitations. The retrospective design and our inability to control for fistula severity may have introduced bias and impacted our findings. Despite adjusting for a variety of confounders such as abscess, immunomodulator use, and time to anti-TNF, we were not able to fully control for fistula complexity. Owing to our sample size, we were also limited in the number of variables that could be chosen for our multivariable model. Although we did not include rectal inflammation and anti-TNF trough concentrations in our final model, both of which have been shown to impact fistula outcomes,16,28 there were no differences for these variables between cohorts when assessed in our univariable analysis.

Another limitation was that treatment success was determined clinically rather than radiographically. Therefore, we were not able to determine the extent of fistula healing. Although multiple magnetic resonance imaging–based scoring indexes (Van Assche score and MAGNIFI-CD index) have been developed, there has yet to be a widely accepted definition for fistula healing.27,29 Finally, the median time from EUA to anti-TNF therapy was 4 months, suggesting that there were delays in initiating therapy for some patients. This was likely related to delays in obtaining drug coverage or access to a gastroenterologist, or patient preference. However, this did not appear to impact outcomes, as our results remained stable in a sensitivity analysis in which EUA exposure was considered positive when performed within 4 months of initiating anti-TNF therapy.

Given these limitations, caution is required when interpreting the results of our study. Our findings do not imply that anti-TNF therapy alone is sufficient to treat all patients with perianal fistulas. Until dedicated prospective trials are conducted, we believe that source control, with a dedicated EUA, is a critical step in managing perianal fistulizing disease when abscesses are present. However, what remains unclear is if anti-TNF therapy alone is sufficient to treat perianal fistulas in the absence of abscesses. Therefore, further prospective studies, that control for fistula severity are required to fully elucidate the role of EUA in management of perianal Crohn’s disease and to determine if a multidisciplinary approach should be universally considered for managing perianal fistulizing disease, as is recommended by current consensus guidelines.13,15

Conclusions

Our single-center retrospective study found that EUA before anti-TNF therapy was not associated with improved fistula outcomes. These results suggest that an EUA may not be universally required prior to initiation anti-TNF therapy for perianal fistulizing study. Future prospective studies that control for fistula severity are required to confirm these findings.

Acknowledgments

The study protocol was approved by the Ottawa Health Sciences Network Research Ethics Board.

Author Contributions

M.C. and J.D.M. were involved in the conception and design of the study. M.C., M.F., and K.C.K.S. acquired the data. M.C., M.F., E.S., and J.D.M. performed the analysis of the data. M.C., M.F., and J.D.M. wrote the article. All authors critically revised the article and approved the final version submitted.

Funding

This work was supported by an institutional grant from the University of Ottawa Department of Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest

J.D.M. has received consultancy fees and/or honoraria from Janssen, AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer. R.K. has received consultancy fees or honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Encycle, Innomar, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Pendopharm, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Alimentiv (formerly Robarts Clinical Trials), Shire, and Takeda Canada outside the submitted work; and has also received research fees from Roche/Genentech. A.D. has received consultancy fees and/or honoraria from AbbVie and Takeda. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on request to the corresponding author.

References

Author notes

These authors contributed equally to the manuscript.