-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elsa Hedling, Hedvig Ördén, Disinformation, deterrence and the politics of attribution, International Affairs, Volume 101, Issue 3, May 2025, Pages 967–986, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaf012

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article unpacks the politics of disinformation attribution as deterrence. Research and policy on disinformation deterrence commonly draw on frameworks inspired by cyber deterrence to address the ‘attribution problem’, thereby overlooking the political aspects underpinning attribution strategies in liberal democracies. Addressing this gap and bringing together disinformation studies and the fourth wave of deterrence theory, the article examines how acts of attribution serve liberal states' attempts at deterring foreign influence operations. In liberal states, disinformation as an external threat intersects with essential processes of public deliberation, and acts of attribution are charged with political risk. Introducing the concept of the ‘uncertainty loop’, the article demonstrates how the flow of uncertainty charges the decision-making situation in disinformation attribution. Drawing on three contemporary empirical cases—interference in the US presidential election of 2016, the Bundestag election in Germany in 2021 and the EU response to the COVID-19 ‘infodemic’ which erupted in 2020, the article illustrates how diverse strategies of attribution, non-attribution and diffused attribution have been navigated by governments. By laying bare the politics of disinformation attribution and advancing a conceptual apparatus for understanding its variations, the article expands current knowledge on disinformation deterrence and speaks to a broader International Relations literature on how deterrence strategies are mediated through political contexts.

How do acts of attribution serve liberal states' attempts at deterring foreign influence operations in their public spheres, and why are they enacted so unevenly? This article nuances the sensitive relationship between domestic politics, the narrow framing of disinformation attribution as a technical question of pinpointing attackers' identities, and the role of disinformation as a security threat to be deterred. As foreign influence operations have (re-)emerged as a critical threat to liberal democracy, efforts to assess and effectively counter their effects have risen on the political agenda. The increase in disinformation campaigns as hostile acts in the context of geopolitical tensions also means that defensive measures serve as deterrence strategies. Like the cybersphere, the information sphere is seen as an extension of physical territory needing credible defence and deterrence.1 Foreign interference in key political processes such as elections poses an existential risk to democratic states. At the same time, addressing the problem of weaponized disinformation pushes government interventions into the public sphere. Therefore, publicly exposing foreign influence campaigns risks interference with deliberation processes and attracting international attention to a ‘structural vulnerability’ within democracies.2 Decisions by governments to attribute campaigns to state or state-like actors are therefore sensitive and charged with uncertainty. The politics surrounding acts of attribution illustrates why deterring disinformation is a challenge, influenced as much by domestic political considerations as by a need to balance geopolitical interests.

Over the past two decades, deterrence theory has undergone a significant expansion. While the fundamental principle of deterrence—influencing an opponent's strategic actions through the perception of cost, benefits and risks—remains consistent, strategies and scenarios have widened to achieve this influence. This expansion reflects geopolitical developments—the shift from American supremacy and East–West bipolarity through nuclear balancing and the gradual inclusion of analytical perspectives outside the traditional domains of rationalist International Relations theory.3 Moreover, emerging technologies and the speed and scope in which they change have been firmly integrated into deterrence scholarship as factors influencing the security dilemma—the risk of misinterpretation in situations of uncertainty.4

In this context of fear over escalation—whether from unchecked provocations or efforts at deterrence—the literature has actively engaged with the cybersphere.5 Cyber deterrence poses many additional challenges to the traditional interaction dynamics between the deterrent and the deterred, conceptualized in the central ‘attribution problem’.6 In the cyber domain, the challenge of identifying a threat actor increases the uncertainty in the deterrence situation.7 The ambiguity surrounding the identities of threat actors also exacerbates the disinformation threat, prompting analysts to classify foreign influence campaigns as a subset of cyber attacks.8 Consequently, the literature on cyber deterrence and attribution offers a technological solution to identifying the sources of disinformation attacks. The potential to counter the skills and low costs of foreign actors' influence campaigns with an international regime for standardized attribution suggests a reduced advantage for attackers, thereby enhancing deterrence. Although the challenges associated with cyber deterrence offer valuable perspectives on how to address the technical uncertainties of disinformation attacks, this literature obscures the political uncertainties shaping decision-making on attribution in the context of disinformation. The problem of disinformation attribution extends beyond identifying who is responsible and includes the politicization of questions of when and how to attribute.

By bringing what we call the ‘uncertainty loop’ into focus, this article shows how attribution intersects with deterrence in the disinformation context and offers new opportunities to study, analyse and assess empirical variations in attribution strategies pursued by governments. Over the past decade there has been a marked increase in disinformation attribution efforts, driven by initiatives to enhance resilience and deterrence. This has been especially evident in intensified efforts on the part of western governments following Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Although the ‘proof’ underlying attribution is seldom disclosed, the inconsistent application of attribution measures and retrospective criticism of failures to attribute reveal the complex and politically charged nature of these decisions. Showing how the uncertainty loop is at play in different strategies for attribution, and how the interaction between capabilities and timing dictates which sources of uncertainty take precedence when actors assess costs, the article highlights the domestic dynamic of deterrence and answers recent calls for an expansion of the contextual circumstances which condition the use of attribution as deterrence.9

The aim of this article is threefold. It seeks to: 1) bring together research strands in disinformation studies and the fourth wave of deterrence theory; 2) advance a conceptual framework for attribution as deterrence in the context of disinformation, by introducing the uncertainty loop and laying bare the politics of alternative attribution strategies; and 3) illustrate variations of attribution as deterrence through established empirical cases of foreign interference. Our analysis should not be read as a structured comparison, but as an analysis of how factors related to timing and political context can explain variation in attribution acts. We begin by outlining the state of the art in deterrence theory, the attribution problem and how the latter speaks to the disinformation domain. We then show how uncertainty flows differently when the domestic information sphere is the battlefield. We discuss how and why the uncertainty loop matters in decision-making by disentangling forms of attribution from non-attribution. We conclude by calling for studies that can advance our knowledge about how the pursuit of deterrence is shaped by present-day disinformation, its propagation, and the surrounding domestic and geopolitical contexts.

Deterrence and the attribution problem

Deterrence is a tool of statecraft used to prevent an adversary from taking an undesirable course of action. The traditional deterrence theory was developed in a Cold War context of nuclear threats and builds heavily on rationalist assumptions. As Miller underlines, deterrence ‘relies on leaders who are rational enough, informed enough, and value their lives and positions of power’.10 Deterrence involves cost–benefit calculations which ‘necessarily presume a high order of rationality and calculability’.11 While any cost–benefit calculation suffers from uncertainty in trying to ‘anticipate what the other will do’,12 the kinetic weaponry upon which deterrence theory was originally moulded allows actors to estimate the threat and the vulnerability of an adversary to an attack.13 Taking such assumptions as a point of departure, an adversary's desired response can be instigated by raising the (perception of) costs involved in pursuing a particular path of action. This can be achieved by signalling a potential punishment or denying an adversary the necessary capabilities to act. Credible retaliation threats are crucial, signalling ‘meaningful pain’14 to deter actors from harmful behaviour. Effective attribution capabilities furthermore play a central part as adversaries must weigh the likelihood of being caught. Thus, attribution is critical to the cost–benefit analysis central to deterrence logic.

As deterrence logic is applied to a novel range of threats—some non-kinetic and asymmetric—the question of attribution emerges as an intricate and pervasive ‘problem’. The cybersecurity literature on deterrence has seen longstanding discussions about the ‘attribution problem’. Cyber attacks are cheaper than kinetic threats, enabling state and non-state actors to interact more equally. The vast number of potential cyber threat actors complicates attribution. Accentuating this problem, threat actors actively exploit the opportunities to obfuscate their identities due to technical issues with traceability in multi-stage attacks.15 Even if the technological devices employed in an attack can be pinpointed, tracing attacks back to individuals or groups and, in a further step, establishing credible links to state threat actors presents a challenge.16 Additionally, assessing damage in the cyber domain is more complex than in the kinetic domain. The early cyber deterrence literature therefore emphasizes ‘perfect technical attribution’ as essential for effective deterrence by punishment.17 At the same time, sometimes even the ‘nature’ of a cyber attack cannot be fully established,18 causing some scholars to ask whether there could even be ‘such a thing’19 as a solid case of cyber attribution.

The cybersecurity literature has produced various technological and methodological solutions to address the attribution problem. Researchers and practitioners have developed advanced tools and techniques to enhance attribution capabilities, improve threat detection and strengthen defences. Many analyses support a two-pronged approach, involving technical expertise in ‘threat intelligence and digital forensics experts advising decision-makers’ in combination with international agreements on a common forensic standard.20 This approach depends on the collection of ‘observable data artifacts’21 and information on threat actors' behaviours—their ‘tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs)’22—to build a credible case for attribution. Such methods address the uncertainties of cyber attacks through predictive modelling, enabling actors to estimate the likelihood of an attack by a specific actor. Technical advancements have significantly improved the potential for identifying threat actors in the cyber domain.23 When technical capabilities are credibly communicated, they also generate a potential for ‘deterrence by detection’,24 discouraging potential attackers by signalling a high likelihood of detection and punishment.

Disinformation, like cyber attacks, stems from the digital age, and both are sometimes referred to as ‘hybrid threats’ or tools of ‘hybrid warfare’.25 Still, they differ significantly in their methods and objectives, as well as their impacts on individuals, organizations and societies. Cyber attacks target technological systems and infrastructure directly, whereas disinformation targets human perception and information environments.26 Nonetheless they are frequently linked, as threat actors often use them together. A cyber attack may precede or follow a foreign influence campaign with the goal of undermining a society or disrupting a political process. For instance, the hacked emails of political candidates can be used to diffuse a disinformation campaign by introducing fake documents among authentic content. Like cyber attacks, a disinformation attack introduces difficulties with ‘attribution of who, what, and potentially why an attack occurred’,27 leaving state actors ‘with questions about who to hold accountable’.28 Nevertheless, establishing intent is necessary in a context where ‘many different actors spread false and misleading information constantly and without necessarily pursuing distinct or readily identifiable aims’,29 and framing the problem of disinformation deterrence in technological terms paves the way for technological solutions.30 Inspired by cybersecurity, disinformation studies have developed complex methods to identify threat actors and disinformation traits.31 Solutions include behaviour taxonomies, forensic analysis techniques,32 tools for detecting deepfakes33 and frameworks for identifying social bots.34 As with ‘deterrence by detection’ within cybersecurity, this forensic monitoring enables punishment of malicious actors and signals deterrence capabilities to potential offenders.35

Technological solutions to the attribution problem also underpin contemporary policy practices on foreign information influence. Concerns with identifying behaviours are embedded in the widely used DISARM framework outlining the TTPs of disinformation perpetrators.36 An overarching focus on identifying ‘foreign’ threat actors in the information environment has similarly contributed to international agreements and cooperation on information-sharing between allies, such as the G7 Rapid Response Mechanism37 and the European Union-wide Rapid Alert System.38 The promise of establishing such recognized attribution frameworks is to put in place a standardized and transparent approach, thereby increasing the legitimacy of attribution statements.

While improving the understanding of threat actor behaviours, the cybersecurity approach to disinformation attribution overlooks a key point from constructivist deterrence scholars: deterrence is also influenced by the political stakes involved.39 Scholars spearheading the ‘fourth wave of deterrence theory’ note that technical attribution only addresses part of the problem with cyber deterrence. Various social and contextual factors feed into the cost–benefit calculation underpinning attribution practices40 and attribution goes beyond identifying a perpetrator.41 In a context of actor and threat complexity, leveraging reputation through attribution has, for instance, emerged as a tool for ‘deterrence by delegitimization’.42 Rather than being a means to an end, using naming and shaming as deterrence tactics43 makes attribution into a ‘distinct form of punishment’.44 Its effectiveness is dependent on social norms and actors' sensitivity to ‘public opinion costs’.45 Yet, it is still unclear ‘whether, how, and under what conditions public attribution—and the threat of shaming’46 functions as a means for deterrence. Calculating the potential effects of deterrence measures is always difficult, but using attribution to delegitimize actors presents a novel problem of calculability, since it serves both domestic and foreign aims.47

Perhaps more than any other threat, foreign influence campaigns demonstrate that the question of a perpetrator's identity is not the only concern of state actors involved in deterrence. Decisions on disinformation attribution are often related to a perceived political need for attribution (or for non-attribution).48 This consideration of political factors echoes arguments from the fourth wave of deterrence theory: deterrence is determined by political processes that are mediated through social context(s) and norms.49 To adequately address the disinformation attribution problem, we must recognize that foreign influence campaigns differ from both kinetic threats and pure cyber threats. Disinformation unsettles the foundations of liberal democracy. It is the very fact that values and opinions can be contested that weaponizes disinformation.50 Disinformation campaigns are known to exploit socio-political cleavages and are most effective when resonating with existing domestic polarization.51 Disinformation as an external threat thereby intersects with essential processes of political deliberation.52 The impact of disinformation is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from ‘authentic’ contestation in public opinion. In some cases, campaigns involve domestic actors,53 or actors from several states working in concert.54 For these reasons, impact assessments of disinformation campaigns are scarce, and questions concerning harmful effects are not yet settled.55 Attribution in a highly polarized domestic context might even generate contrary results, since ‘overstating the power of propaganda risks amplifying not only the original falsehood but also an even more corrosive and polarizing narrative’.56

A diverse body of critical and constructivist scholarship has emphasized the politics involved in attributing disinformation. For instance, attribution theory highlights how people perceive behaviour and assign responsibility based on causal information.57 This lens helps explain how public attribution involves blaming an actor for spreading disinformation, particularly in politicized, polarized or populist contexts.58 In an ideologically charged environment, citizens concerned with disinformation as a threat may display an ‘attribution bias’59 and ‘selectively attribute blame to politicians and media from the opposite side’.60 The inherent link between attribution and blame also allows politicians61 to use attribution as a political tool to ‘delegitimise or attack political opponents’.62 By emphasizing these potentially harmful implications of attribution, this research brings attention to the precarious politics of attributing disinformation to citizens or political opponents in a democratic context.

Critical security scholars focus instead on the perils of attributing disinformation to foreign adversaries, but highlight similar risks to democratic debate.63 While the foreign/domestic distinction is often mobilized to separate illegitimate disinformation from legitimate public debate,64 attributing disinformation to foreign adversaries might raise the political stakes domestically. Attribution in a context of national security not only allows actors to ‘denounce certain opinions’,65 but also to describe citizens or particular communities as ‘useful idiots’66 or potential ‘fifth columns’.67 The blame relayed through attribution is then associated with acting for the benefit of a foreign adversary.

These insights in disinformation studies show how attribution is productive of political risk. The risk tied to attribution arises from a web of uncertainties that need to be factored into the deterrence strategies used against foreign influence operations. Aligned with the fourth wave of deterrence theory, a thorough understanding of deterrence must encompass the material capabilities and technological aspects of attribution and the intersubjective social context in which deterrence is enacted.

The politics of attribution

Building on these arguments, we conceptualize the politics of attribution as the interaction between sources of uncertainty and risk that are related to the capability to attribute and the timing of the political decision to attribute. While technical attribution capabilities can be purposefully developed to strengthen ‘deterrence by detection’, other sources of uncertainty arise from both domestic and international politics. The presence of such uncertainties compels governments to carefully navigate different deterrence scenarios and can explain variations in attribution strategies. Unpacking the politics of disinformation attribution destabilizes the traditional interactional dynamics of deterrence (between the deterrer and the deterred) and demonstrates why foreign information influence is ‘a unique vulnerability’.68

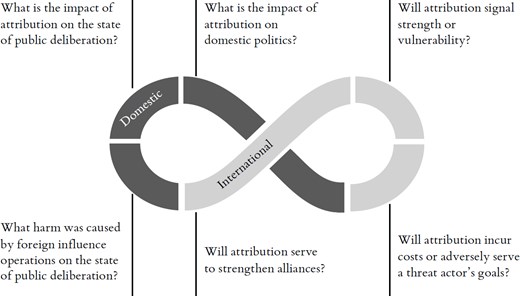

In figure 1, below, we envision decision-making processes in relation to the attribution of disinformation as an ‘uncertainty loop’ where timing dictates which sources of uncertainty and risk take precedence when government actors assess costs at a given moment. The loop thereby adds a layer of complexity to the interactional dynamics of deterrence, where timing is seen as relative to the undesirable actions of an adversary,69 and brings a domestic component into deterrence theory.

In the uncertainty loop, a continuous flow of uncertainty charges the decision-making situation. Decisions to attribute disinformation (or refrain from attribution) are based on actors' cost–benefit calculations at any given time. Once a decision has been made, however, the timing of that decision may align with a new set of costs entering the equation. This temporal complexity springs from the specific political-contextual uncertainties affecting cost–benefit calculations in relation to disinformation attribution. Uncertainties spring from: 1) the nature of foreign information influence as an external threat intersecting with domestic processes of political deliberation and 2) the act of public attribution as potentially productive of political risk. On the domestic side of the loop, states can assess neither the harmful impact of influence operations in their own ‘territory’ nor the impact that attribution of foreign interference may have on inter-party relations, the state of public deliberation or levels of public trust. On the international side of the loop, there is uncertainty about whether attribution signals vulnerability or strength to the outside world, whether it would strengthen alliances, and whether it would incur costs to the perpetrator or, in fact, adversely serve their goal. Due to the inherent difficulty of separating domestic politics from the external threat, domestic political risk can also persist even after an attribution decision is made. Because uncertainties continuously generate novel conditions for attribution, it is not the mere accumulation of uncertainty that complicates decision-making, but the unpredictable changes themselves.

Alongside technical attribution capabilities, the dynamic sources of political uncertainty outlined in the loop throw some much-needed70 light upon the conditions that governments need to consider when navigating public attribution of disinformation. Further grasping the politics of attribution requires that we distinguish between a set of attribution strategies available to governments, and how these strategies relate to deterrence.

Public attribution refers to instances where governments publicly identify and respond to interference using measures such as sanctions, indictments, media regulations, bans, official statements or counter-operations. In the disinformation context, acts of public attribution serve deterrence by imposing costs on foreign actors who seek to undermine democratic processes. They do so by exposing attackers' identities, laying bare the tactics and strategies they use and condemning them by reference to international law. By holding state actors, groups or individuals publicly accountable for their efforts to interfere in democratic politics, they are ‘named and shamed’. At the same time, governments signal capability and resolve when calling them out.71 In the logic of ‘deterrence by delegitimization’, public attribution thereby works by imposing social costs while denying the attacker political victories.72 The decision to pursue this strategy will, however, depend on the conditions of uncertainty charging the situation at that point in time. The likelihood of attribution around an upcoming election can either increase or decrease based on the policy agenda and the ‘public mood’,73 including perceived levels of resilience.74 If the public is polarized on key policy issues, attribution might be seen as further politicizing the situation. Additionally, if the public shows ideological sympathy with the attackers' regime, attribution could be rejected.75 In cases where societal resilience is high and disinformation is unlikely to cause significant harm, governments might strategically choose to withhold attribution.

Non-attribution is not merely the absence of attribution or a misdirection of blame, but a deliberate choice to refrain from publicly assigning blame despite having evidence. This approach is therefore distinct from an inability to attribute due to underdeveloped capabilities for ‘deterrence by detection’, and centres on the strategic political implications of attribution. Non-attribution can act as a deterrent by preserving ambiguity about the nature of threats across different audiences. Decisions to pursue non-attribution are influenced by assessments of domestic resilience capabilities and the potential costs both to the perpetrator and in the domestic sphere. Unlike ‘deterrence by denial’, which focuses on building societal resilience, non-attribution weighs the risks of backlash and other domestic consequences. It involves a calculated judgement rather than ignoring the perpetrator outright, and considers how attribution might have unintended negative effects. Timing and capabilities remain crucial, as non-attribution can precede eventual attribution, with strategies evolving based on situational factors and accumulating forensic evidence to reduce uncertainty in the domestic context.

Finally, diffused attribution involves managing the balance between being transparent and maintaining discretion in public discourse. By allowing or informally encouraging credible non-state actors or international organizations to publicly assign blame and suggest consequences, governments can support attribution without directly intervening. This method is akin to ‘deterrence by detection’, in that it publicly demonstrates a technical ability to identify threat actors, but crucially enables shared responsibility for public attribution. Diffused attribution—for instance EU member states collectively imposing sanctions76—thereby effectively manages the domestic political impact while signalling international determination. A case in point is the EU's suspension of the activities of the Russian state-owned broadcasters Russia Today (now RT) and Sputnik, both within and directed at EU member states, due to the broadcasters' spread of disinformation.77 This approach helps manage uncertainty and reduce vulnerabilities by carefully balancing domestic and geopolitical risks while avoiding publicly assigning blame to citizens. It also strengthens deterrence by fostering credible alliances against threat actors while avoiding direct government intervention in the public sphere.

Public attribution and its alternatives

To further explore the politics of attribution, we will illustrate how the uncertainty loop drives variation in attribution acts by examining three recent cases of foreign interference involving disinformation: the 2016 presidential election in the United States; the 2021 federal election in Germany; and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–21. The cases were selected because all three involved reports that there was substantial evidence of disinformation, yet governments adopted distinct approaches to attribution. We argue that these diverging responses are driven by the specific uncertainties permeating the political situation at any given time. The cases differ in their liberal democratic contexts (for instance in terms of levels of cohesion and polarization) and in the range of disclosed sources that determine the strength of evidence available to governments. Our analysis is not focused on evaluating the robustness or effectiveness of attribution, but on exploring how the timing of political circumstances feed into attribution decisions. We cannot determine causal effects, but rather offer a deeper understanding of the political-contextual factors that shape and drive these choices. The logic of inquiry is inductive, and our method of analysis serves to trace political decisions on attribution through a triangulation of publicly available documents, reports and news media reporting. While the lack of public attribution naturally results in a sparser paper trail, the timing of political events and eventual acts of attribution have nevertheless provided us with enough empirical material for our illustrative analysis.

Public attribution

Since 2016, the US government has publicly attributed both disinformation and cyber offences with great frequency, but attention to the timing of attribution statements suggests that a degree of political risk and uncertainty is at play as actors assess attribution costs. The US intelligence community notably exposed Russia's disinformation activities during the 2016 presidential election. This disclosure prompted four investigations assessing the potential electoral harm of the threat and the responses of the government and the Federal Bureau of Intelligence (FBI).78 The reports, totalling 2,500 pages of evidence and testimonies, illustrate how Russia's targeted election interference intersected with domestic political polarization, complicating efforts to investigate and attribute foreign interference. Despite possessing the technical capabilities for attribution, these political factors constrained the US strategy of ‘deterrence by detection’.

President Barack Obama first issued sanctions against Russia on 29 December 2016 for ‘aggressive harassment of U.S. officials and cyber operations aimed at the U.S. election’.79 Just over a week afterwards, on 6 January 2017, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released its initial report stating that Russian President Vladimir Putin had orchestrated a campaign to undermine confidence in the US democratic process and to harm Hillary Clinton's candidacy.80 The Obama administration refrained from attributing these actions during the campaigning that had begun after Clinton and Donald Trump accepted their party nominations for the presidency in July 2016, leading up to the election on 8 November. The timing of attributing statements and the subsequent report findings shed light on the persistent flow of uncertainty over how attribution would affect the election outcome. The report by special counsel Robert S. Mueller III in April 2019 confirmed that despite warnings to the Russian regime, and even though the FBI had initiated an investigation as early as July,81 the Obama administration had intentionally delayed public attribution.

The report that was released by special counsel John Durham in 2023 further revealed that uncertainty about how the investigations would be framed in public narratives and the risk of a backlash against politically motivated attribution were involved in the assessment. Most notably, it was perceived that attribution would have benefited the Clinton campaign, which actively sought to highlight the alleged ties between the Russian government and the Trump campaign in the latter months of 2016.82 Meanwhile, the Trump campaign capitalized on anti-establishment sentiments and warnings of a ‘rigged election’. The risk was thus that a backlash following a perceived ‘attribution bias’ would negatively influence the legitimacy of the election. Delaying attribution was a way of demonstrating detection capabilities to Russia while not risking the domestic costs of meddling in a polarized electorate. However, Republicans—not least President Trump—immediately used the findings of the Mueller report (e.g. the criticism of delayed attribution) to direct blame at the Obama administration, deflecting discussions on the impact on the election outcome.83 Criticism of the Obama administration increased when the bipartisan Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released its multi-volume report. Volume 3, published in February 2020, suggested that

The Obama administration … tempered its response over concerns about appearing to act politically on behalf of one candidate, undermining public confidence in the election, and provoking additional Russian actions. Further, administration officials' options were limited by incomplete information about the threat and having a narrow slate of response options from which to draw.84

While the report was more vocal in directing blame at Obama, it also went further than the Mueller report in detailing the links between the Trump campaign and the Russian state. In addition to the uncertainty about how the calling out of Clinton's unfavourable conditions would be received by the electorate, and about what measures to use in a new situation, the Obama administration was criticized—at least by its opponents—for being lenient with Russia to secure the legacy of the Iran nuclear deal framework.85 Hence, there was also geopolitical uncertainty about how an adversary (and its allies) would respond to a deterring move and the potential cost of retaliation.

When Trump assumed office in January 2017, the question of Russian interference was undoubtedly sensitive. The Trump administration opted to continue to downplay the results of investigations while echoing the failure of the Obama administration to protect the election. The Office of Foreign Assets Control of the US Department of the Treasury did not issue sanctions against Russia for its 2016 election interference until 2018.86 Still, Trump made headlines in July 2018 when, after his Helsinki summit meeting with Putin, he publicly sided with the Russian president over the FBI's allegations (by then proven) of interference, stating ‘President Putin says it's not Russia. I don't see any reason why it would be.’87 Thus Trump again mobilized the flow of uncertainty to his own advantage by pointing fingers at Obama's lack of resolve while simultaneously avoiding costs to his own administration.88

By contrast, the Biden administration swiftly addressed Russia's ‘harmful foreign activities’ following the 2020 election through executive orders, economic sanctions and expulsions of diplomats.89 The attribution efforts bolstered renewed commitment to multilateralism amid strong domestic and international signals, including expanded sanctions in 2021 targeting Russia-sponsored influence operations and safeguarding US national security.90 The flow of uncertainty had shifted, however, and the timing of the Biden administration's decision to attribute was most likely also influenced by other calculations of costs, such as trade-offs in the US debate on privacy rights and the booming digital economy. Big tech, the largest IT companies and dominant owners of social media platforms, represents a growing portion of the US economy. Whereas the EU has leaned towards increasing the accountability of social media platforms that enable and diffuse disinformation (along with other harmful content), the US electorate is divided over the issue of regulation.91 At the same time, the Biden administration has been criticized for its inability to act on the ‘misinformation plague’ and its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.92 In the US context, public attribution of Russian interference thereby also reassured the public of capable deterrence of ‘a foreign threat’ in the absence of regulatory reform.

Non-attribution

In the case of Germany's 2021 Bundestag election, despite reported disinformation campaigns targeting Annalena Baerbock, the co-leader of Alliance 90/The Greens, officials chose not to publicly attribute the interference to foreign actors. In this example of ‘non-attribution’, the flow of uncertainty led to a distinct pattern of balancing domestic risks and calculating the costs of deterrence. Despite Germany being a prime target for Russian disinformation efforts among EU member states since 2015,93 successive coalition governments had been hesitant in risking the country's stability and reform efforts by reversing Germany's rapprochement with Russia.94 In the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Germany aimed to reconcile economic relations—notably in energy and joint ventures like the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project—with the EU's stance against Russia's breaches of international law. Germany's balancing strategy and stance on the disinformation threat therefore centred on ‘deterrence by denial’ and bolstering resilience to prevent harm on the state of public deliberation. Anticipating disinformation and cyber threats during the 2021 federal election, precautionary measures were implemented that included cybersecurity measures, public education initiatives and proactive collaborations with social media platforms.95 However, the distinctively gendered disinformation campaigns targeting Annalena Baerbock, the sole female candidate for the chancellorship, were unexpectedly impactful.96 Baerbock faced disproportionate attacks, including misogynistic narratives and doctored nude images portraying her as a former sex worker.97 Baerbock's criticism of Nord Stream 2 further fuelled these attacks, which were linked to Russian state actors and media.98 In fact, since 2021 Russian state media have continued to circulate the false claims of Baerbock's past along with the images.99 Although the origin of this campaign and its online amplification was linked to Russia, German media also engaged in sexist rhetoric questioning of Baerbock's ability to balance leadership with motherhood.100 The sensitive nature of gender-based attacks thus intersected with value conservatism and ‘home-grown misogyny’, complicating the assessment of interference as well as introducing risks of domestic backlash resulting from attribution. Threat actors—in this context most notably Russia—certainly fuelled negative campaigning in Germany, but the resonance of narratives reflected a polarization over both foreign policy (and the stance on Russia) and gender norms. Amid high stakes and Germany's political transition away from Angela Merkel's leadership, public attribution of interference was likely avoided to prevent further polarization and preserve stability, highlighting the complexity of addressing both deterrence interests and domestic risks to electoral integrity. Moreover, the combination of non-attribution and prevailing uncertainty could act as a deterrent by preserving ambiguity about the disinformation threat among the German public.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022 marked the end of Germany's policy of rapprochement101 and produced a new context for the politics of attribution. Since 2022, actions by Germany further signal deterrence-seeking and a shift from its choice of non-attribution during the 2021 federal elections. The German government has made a series of accusations of Russian disinformation,102 including digital forensic proof of a large-scale disinformation campaign aimed at discouraging public support for German aid to Ukraine.103

In May 2024 Germany went so far as to temporarily recall its ambassador from Moscow, following which then-foreign minister Baerbock publicly attributed interference in German politics to Russian military cyber operators, specifically the advanced persistent threat group APT28 (also known as Fancy Bear or Pawn Storm).104 The cyber attack was specifically framed as a threat to the integrity of upcoming European Parliament elections, as well as regional elections in Germany and those in neighbouring states. This strategic move positioned Germany's evolving stance in preparation for the 2025 Bundestag election by providing clear ‘deterrence by detection’ signals to Russia while mitigating the uncertainties that had charged the 2021 election. The emphasis on the European Parliament elections was not just an opportunity to combat disinformation while keeping a safe distance from the upcoming federal election: it was also a pivotal moment to expose Russia's geopolitical interests and the stakes of the war in Ukraine to the German public, as well as to emphasize Germany's commitment to its international allies through collective deterrence by both punishment (sanctions and public attribution) and denial (resilience-building).

Diffused attribution

During the COVID-19 pandemic, European governments leveraged EU frameworks to balance the protection of domestic accountability with deterrence interests. The European Commission initially aimed to combat harmful COVID-related misinformation by using the Code of Practice on Disinformation, a voluntary self-regulation initiative for online platforms.105 Despite this existing measure, European governments also pursued EU-level attribution amid significant domestic political risks.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a challenge for democratic governments. The uncertainties related to the origins of the virus, its transmission and, later, the safety of the newly developed vaccines were accompanied by an ‘infodemic’106 involving the spread of false and misleading information. The World Health Organization concluded that the spread of disinformation posed ‘profound health and public safety risks’.107 This was especially true for the vaccine-related disinformation, which threatened to reduce the uptake of vaccines. Much COVID-related disinformation—according to some, the bulk of dis- and misinformation108—was disseminated by domestic or intra-EU actors for financial or political gain,109 or spread by citizens experiencing uncertainty and fear. A set of coordinated foreign influence campaigns was, however, linked to threat actors, notably Russia and China. China focused on deflecting blame for the spread of the virus by spreading narratives on western failures and enhancing its position on the world stage,110 and Russia aimed to weaken public trust in European governments' responses to the pandemic.111 In-depth studies show how ‘French and German-language reporting from Russian state media highlighted acts of civil disobedience, and tensions with public authorities amid the pandemic’, and thereby tried to fuel existing domestic divisiveness.112

Throughout the pandemic, European populations held deeply divided views on the stringent government measures employed to tackle the virus, such as lockdowns and, in some states, compulsory vaccination schemes. In many EU states trust in government was low and resilience to disinformation sometimes poor; groups of citizens engaged in public protests.113 In countries like Germany and Austria, government responses to the pandemic were politicized by domestic actors. Opposition actors saw an opportunity to gather support for their causes,114 while extremists exploited growing anti-lockdown sentiments within parts of the population.115 These aspects charged the uncertainty loop with a complex set of domestic political risks. Any form of public distribution of blame or social punishment risked being used by domestic political actors to mobilize more support. Attribution of disinformation—even disinformation by foreign adversaries—thereby risked feeding into existing polarized narratives on government overreach and vaccine safety while generating increased support for actors in the opposition.

Rather than pursuing a strict strategy of non-attribution, however, European governments navigated the flow of uncertainty by shifting attribution to the EU level. Beginning in 2020, the European External Action Service (EEAS) published a series of special reports116 on the COVID-19 infodemic, attributing coordinated disinformation campaigns to Russia and China (and, to a certain extent, to Iran).117 The EEAS argued that these threat actors were striving to ‘undermine trust in western-made vaccines, EU institutions and western/European vaccination strategies’ and to fuel ‘anti-vaccination movements within the EU’.118 Following an update in April 2020,119 in an opening statement in the European Parliament, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, reiterated the attributional intent by underlining that the report ‘very clearly points out state-sponsored disinformation campaigns and very specifically names the actors behind them—including China’.120 This last comment was made following criticism that the EEAS tried to avoid attributing disinformation to Chinese state actors,121 and Borrell underlined that ‘[t]here was no “watering down” of our findings, however uncomfortable they could be’ and indicated the potential use of additional diplomatic measures.122 By attributing coordinated campaigns to adversary states, the EU aimed to signal resolve internationally through a collective demonstration of capabilities for deterrence by detection, while allowing individual member states to manage domestic political risk. By moving attribution to the EU level, governments could avoid unfavourable political outcomes generated through public attribution and the overt blaming of citizens, such as enhanced polarization and a display of domestic societal vulnerabilities to COVID-19 disinformation. Furthermore, signalling resolve towards Russia and Iran bolstered the EU's broader geopolitical deterrence stance while navigating uncertainties amid US–China tensions during Trump's presidency.123 Additionally, the diffused attribution strategy potentially enhanced domestic resilience by attributing COVID-19 disinformation to foreign adversaries, thereby discouraging acceptance of similar narratives among EU citizens.

Even with these efforts to mitigate multiple uncertainties, attribution was not without criticism. Following the release of the EEAS special reports, the EU DisinfoLab, an independent non-profit organization producing knowledge on disinformation, published a statement calling for EU institutions to be ‘cautious with attribution’ of foreign influence operations to Russia.124 Arguing that ‘there is absolutely no evidence that these [pro-Kremlin media] outlets are the “architects” of the massive disinformation around the coronavirus’, the statement underscored that ‘an overwhelming majority of the disinformation and misinformation’ was internal to the EU and required a different toolbox.125

Conclusion

This article has argued that attribution must be seen as a political challenge, and that variations in governments' pursuit of deterrence through disinformation attribution can be better understood through attention to the complex and dynamic flow of political uncertainties conditioning the decision-making situation. By attending to the politics of attribution, and introducing the ‘uncertainty loop’, the article makes several contributions to current discussions on disinformation deterrence.

First, emphasizing timing as a key aspect alongside attribution capabilities highlighted in the cyber deterrence literature, we show how deterrence in the information sphere necessitates attention to a set of highly dynamic political uncertainties in addition to technical attribution models. While the capability to attribute is crucial for deterrence, the absence of attribution does not necessarily mean the absence of such capabilities. Instead, governments might refrain from attribution due to perceived political costs. Second, by also taking seriously the domestic factors at play in disinformation deterrence, the ‘uncertainty loop’ adds to broader discussions within deterrence theory. Crucially, our model challenges the traditional interactional dynamic of deterrence and shows how political costs might also mean domestic political costs. Third, by conceptualizing three different variations of attribution and empirically illustrating how the uncertainty loop allows for different attribution strategies, the article speaks to current debates about the circumstances conditioning the use of ‘naming and shaming’, and appeals to social punishment as a deterrency strategy. Taken together, these novel insights could potentially be applied to better understand deterrence strategies employed in relation to a broader range of non-kinetic threats which interact with domestic factors, and in contexts where actors draw on social norms and the threat of social punishment.

Footnotes

Randolph H. Pherson, Penelope Mort Ranta and Casey Cannon, ‘Strategies for combating the scourge of digital disinformation’, International Journal of Intelligence and Counter Intelligence 34: 2, 2021, pp. 316–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2020.1789425.

Spencer McKay and Chris Tenove, ‘Disinformation as a threat to deliberative democracy’, Political Research Quarterly 74: 3, 2020, pp. 703–17, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912920938143.

Amir Lupovici, ‘The emerging fourth wave of deterrence theory—toward a new research agenda’, International Studies Quarterly 54: 3, 2010, pp. 705–32, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00606.x; Alex Wilner, ‘Deterrence by de-legitimisation in the information environment: concept, theory, and practice’, in Eric Ouellet, Madeleine D'Agata and Keith Stewart, eds, Deterrence in the 21st century: statecraft in the information age (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2024).

Amir Lupovici, ‘Ontological security, cyber technology, and states' responses’, European Journal of International Relations 29: 1, 2023, pp. 153–78, https://doi.org/10.1177/13540661221130958.

Myriam Dunn Cavelty, ‘Breaking the cyber-security dilemma: aligning security needs and removing vulnerabilities’, Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 20, 2014, pp. 701–15, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-014-9551-y; Carly E. Beckerman, ‘Is there a cyber security dilemma?’, Journal of Cybersecurity 8: 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyac012.

Jon R. Lindsay, ‘Tipping the scales: the attribution problem and the feasibility of deterrence against cyberattack’, Journal of Cybersecurity 1: 1, 2015, pp. 53–67, https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyv003.

Florian Skopik and Timea Pahi, ‘Under false flag: using technical artifacts for cyber attack attribution’, Cybersecurity 3: 8, 2020, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42400-020-00048-4.

Cyber attacks target information security through malware, viruses and trojans. Disinformation spreads misappropriated information, manipulated data or deepfakes to sow discord in the public sphere. However, cyber attacks and disinformation campaigns are often pursued in tandem by diffusing leaks manipulated by false information. An example is the case of the ‘Macron leaks’ in 2017. See for instance: Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, The ‘Macron leaks’ operation: a post-mortem (Washington DC: Atlantic Council, 2019), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The_Macron_Leaks_Operation-A_Post-Mortem.pdf. (Unless otherwise noted at point of citation, all URLs cited in this article were accessible on 14 Feb. 2025.).

Alex S. Wilner, ‘US cyber deterrence: practice guiding theory’, Journal of Strategic Studies 43: 2, 2020, pp. 245–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2018.1563779.

Michael Miller, ‘Nuclear attribution as deterrence’, The Nonproliferation Review 14: 1, 2007, pp. 33–60 at p. 43, https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700601178465.

Martin C. Libicki, ‘Expectations of cyber deterrence’, Strategic Studies Quarterly 12: 4, 2018, pp. 44–57 at p. 47.

Robert Jervis, ‘Some thoughts on deterrence in the cyber era’, Journal of Information Warfare 15: 2, 2016, pp. 66–73 at p. 68.

Libicki, ‘Expectations of cyber deterrence’, p. 51.

Ben Buchanan, ‘Cyber deterrence isn't MAD; it's mosaic’, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 4, 2014, pp. 130–40.

Richard Clayton, Anonymity and traceability in cyberspace (Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge, Computer Laboratory, 2005), https://doi.org/10.48456/tr-653; National Research Council, Proceedings of a workshop on deterring cyberattacks: informing strategies and developing options for US policy (Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2010); Herbert Lin, ‘Attribution of malicious cyber incidents: from soup to nuts’, Journal of International Affairs 70: 1, 2016, pp. 75–137.

Ronald J. Deibert, Rafal Rohozinski and Masashi Crete-Nishihata, ‘Cyclones in cyberspace: information shaping and denial in the 2008 Russia–Georgia war’, Security Dialogue 43: 1, 2012, pp. 3–24, https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010611431079.

W. Earl Boebert, ‘A survey of challenges in attribution’, in National Research Council, Proceedings of a workshop, p. 51.

Susan W. Brenner, ‘At light speed: attribution and response to cybercrime/terrorism/warfare’, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 97: 2, 2007, pp. 379–475.

Brian Bartholomew and Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade, Wave your false flags! Deception tactics muddying attribution in targeted attacks, paper presented at Virus Bulletin Conference, Denver, CO, 5–7 Oct. 2016, p. ix, available at https://media.kasperskycontenthub.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2017/10/20114955/Bartholomew-GuerreroSaade-VB2016.pdf.

Milton Mueller, Karl Grindal, Brenden Kuerbis and Farzaneh Badiei, ‘Cyber attribution: can a new institution achieve transnational credibility?’, The Cyber Defense Review 4: 1, 2019, pp. 107–24 at p. 108, https://cyberdefensereview.army.mil/Portals/6/9_mueller_cdr_V4N1.pdf.

Brenden Kuerbis, Farzaneh Badiei, Karl Grindal and Milton Mueller, ‘Understanding transnational cyber attribution: moving from “whodunit” to who did it’, in Myriam Dunn Cavelty and Andreas Wenger, eds, Cyber security politics: socio-technological transformations and political fragmentation (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2022), p. 227.

Kuerbis et al., ‘Understanding transnational cyber attribution’, p. 222.

Mueller et al., ‘Cyber attribution’.

Jon Lindsay and Erik Gartzke, ‘Coercion through cyberspace: the stability–instability paradox revisited’, in Kelly M. Greenhill and Peter Krause, eds, Coercion: the power to hurt in international politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 192.

Mikael Wigell, ‘Hybrid interference as a wedge strategy: a theory of external interference in liberal democracy’, International Affairs 95: 2, 2019, pp. 255–75, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz096; Elsa Hedling, ‘Transforming practices of diplomacy: the European External Action Service and digital disinformation’, International Affairs 97: 3, 2021, pp. 841–59, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab035.

James H. Fetzer, ‘Information: does it have to be true?’, Minds and Machines, vol. 14, 2004, pp. 223–9, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MIND.0000021682.61365.56.

Aaron F. Brantly, ‘The cyber deterrence problem’, in Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CyCon), 2018, p. 45, https://doi.org/10.23919/CYCON.2018.8405009.

Garry S. Floyd, Jr, ‘Attribution and operational art: implications for competing in time’, Strategic Studies Quarterly 12: 2, 2018, pp. 17–55, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-12_Issue-2/Floyd.pdf.

Henning Lahmann, ‘Infecting the mind: establishing responsibility for transboundary disinformation’, European Journal of International Law 33: 2, 2022, pp. 411–40, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chac023.

Anke Sophia Obendiek and Timo Seidl, ‘The (false) promise of solutionism: ideational business power and the construction of epistemic authority in digital security governance’, Journal of European Public Policy 30: 7, 2023, pp. 1305–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2172060.

Tom Robertson and Teah Pelechaty, Addressing attribution: theorising a model to identify Russian disinformation campaigns online (Calgary: Canadian Global Affairs Institute, 2022), https://www.cgai.ca/addressing_attribution_theorizing_a_model_to_identify_russian_disinformation_campaigns_online.

Andrew Dawson and Martin Innes, ‘How Russia's internet research agency built its disinformation campaign’, Political Quarterly 90: 2, 2019, pp. 245–56 at p. 253, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12690.

Samuel Henrique Silva et al., ‘Deepfake forensics analysis: an explainable hierarchical ensemble of weakly supervised models’, Forensic Science International: Synergy, vol. 4, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsisyn.2022.100217.

Sanjay Goel and Brian Nussbaum, ‘Attribution across cyber attack types: network intrusions and information operations’, IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society, vol. 2, 2021, pp. 1082–93, https://doi.org/10.1109/OJCOMS.2021.3074591.

H. Akin Unver and Arhan S. Ertan, ‘The strategic logic of digital disinformation: offence, defence and deterrence in information warfare’, in Rubén Arcos, Irena Chiru and Cristina Ivan, eds, Routledge handbook of disinformation and national security (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2024), pp. 192–207.

S. J. Terp and Pablo Breuer, ‘DISARM: a framework for analysis of disinformation campaigns’, in 2022 IEEE Conference on Cognitive and Computational Aspects of Situation Management (CogSIMA), 2022, pp. 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/CogSIMA54611.2022.9830669.

Nicole J. Jackson, ‘The Canadian government's response to foreign disinformation: rhetoric, stated policy intentions, and practices’, International Journal 76: 4, 2021, pp. 544–63 at p. 560, https://doi.org/10.1177/00207020221076402.

European External Action Service, ‘Tackling disinformation, foreign information manipulation & interference, updated 14 Nov. 2024, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/tackling-disinformation-foreign-information-manipulation-interference.

Thomas Rid and Ben Buchanan, ‘Attributing cyber attacks’, Journal of Strategic Studies 38: 1–2, 2015, pp. 4–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2014.977382.

Amir Lupovici, ‘The “attribution problem” and the social construction of “violence”: taking cyber deterrence literature a step forward’, International Studies Perspectives 17: 3, 2016, pp. 322–42, https://doi.org/10.1111/insp.12082.

Jeffrey W. Knopf, ‘The fourth wave in deterrence research’, Contemporary Security Policy 31: 1, 2010, pp. 1–33 at p. 25, https://doi.org/10.1080/13523261003640819.

J. Marshall Palmer and Alex Wilner, ‘Deterrence and foreign election intervention: securing democracy through punishment, denial, and delegitimization’, Journal of Global Security Studies 9: 2, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogae011.

Marshall Palmer and Wilner, ‘Deterrence and foreign election intervention’.

Wilner, ‘US cyber deterrence’, pp. 270–1.

Amir Lupovici, ‘Deterrence through inflicting costs: between deterrence by punishment and deterrence by denial’, International Studies Review 25: 3, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viad036.

Wilner, ‘US cyber deterrence’, p. 171.

Marshall Palmer and Wilner, ‘Deterrence and foreign election intervention’.

Lupovici, ‘The “attribution problem” and the social construction of “violence”’.

Lupovici, ‘The “attribution problem” and the social construction of “violence”’, p. 322.

Henry Farrell and Bruce Schneier, Common-knowledge attacks on democracy (Cambridge, MA: Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, 2018), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3273111.

Vincent Charles Keating and Olivier Schmitt, ‘Ideology and influence in the debate over Russian election interference’, International Politics, vol. 58, 2021, pp. 757–71, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-020-00270-4.

Thomas Rid and Ben Buchanan, ‘Hacking democracy’, SAIS Review of International Affairs 38: 1, 2018, pp. 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2018.0001.

Sophie Vériter, ‘European democracy and counter-disinformation: toward a new paradigm?’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 14 Dec. 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/12/european-democracy-and-counter-disinformation-toward-a-new-paradigm.

Vilmer, The ‘Macron leaks’ operation: a post-mortem.

Wolf J. Schünemann, ‘A threat to democracies? An overview of theoretical approaches and empirical measurements for studying the effects of disinformation’, in Dunn Cavelty and Wenger, Cyber security politics, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003110224-4.

Olga Belogolova, Lee Foster, Thomas Rid and Gavin Wilde, ‘Don't hype the disinformation threat: downplaying the risk helps foreign propagandists—but so does exaggerating it’, Foreign Affairs, 3 May 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/dont-hype-disinformation-threat.

Brian H. Spitzberg and Valerie Manusov, ‘Attribution theory: finding good cause in the search for theory’, in Dawn O. Braithwaite and Paul Schrodt, eds, Engaging theories in interpersonal communication (New York and Abingdon: Routledge, 2022), pp. 39–51.

Michael Hameleers, ‘Populist disinformation: exploring intersections between online populism and disinformation in the US and the Netherlands’, Politics and Governance 8: 1, 2020, pp. 146–57, https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i1.2478.

Michael Hameleers and Anna Brosius, ‘You are wrong because I am right! The perceived causes and ideological biases of misinformation beliefs’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 34: 1, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edab028.

Jianing Li and Min-Hsin Su, ‘Real talk about fake news: identity language and disconnected networks of the US public's “fake news” discourse on Twitter’, Social Media + Society 6: 2, 2020, p. 3, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120916841.

Michael Hameleers and Sophie Minihold, ‘Constructing discourses on (un)truthfulness: attributions of reality, misinformation, and disinformation by politicians in a comparative social media setting’, Communication Research 49: 8, 2022, pp. 1176–99, https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220982762.

Hameleers and Minihold, ‘Constructing discourses on (un)truthfulness’, p. 1177.

Linda Monsees, ‘Information disorder, fake news and the future of democracy’, Globalizations 20: 1, 2023, pp. 153–68 at p. 161, https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2021.1927470. See also, for instance: Jakub Eberle and Jan Daniel, Politics of hybrid warfare: the remaking of security in Czechia after 2014 (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-32703-2.

Hedvig Ördén and James Pamment, What is so foreign about foreign influence operations? (Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2022), https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/01/what-is-so-foreign-about-foreign-influence-operations.

Monsees, ‘Information disorder’, p. 153.

Jan Daniel and Jakub Eberle, ‘Speaking of hybrid warfare: multiple narratives and differing expertise in the “hybrid warfare” debate in Czechia’, Cooperation and Conflict 56: 4, 2021, pp. 432–53 at p. 443, https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367211000799.

Eberle and Daniel, Politics of hybrid warfare, p. 12. See also Hedvig Ördén, ‘The neuropolitical imaginaries of cognitive warfare’, Security Dialogue 55: 6, 2024, pp. 607–24, https://doi.org/10.1177/09670106241253527.

James Pamment and Björn Palmertz, ‘Deterrence by denial and resilience building’, in Arcos, Chiru and Ivan, eds, Routledge handbook of disinformation and national security, p. 25.

Lupovici, ‘Deterrence through inflicting costs’.

Wilner, ‘US cyber deterrence’, p. 171.

Jon R. Lindsay, ‘Tipping the scales: the attribution problem and the feasibility of deterrence against cyberattack’, Journal of Cybersecurity 1: 1, 2015, pp. 53–67, https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyv003.

Lupovici, ‘Deterrence through inflicting costs’, p. 11.

Mitchell Dean, ‘Political acclamation, social media and the public mood’, European Journal of Social Theory 20: 3, 2017, pp. 417–34, https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431016645589.

Edda Humprecht et al., ‘The sharing of disinformation in cross-national comparison: analysing patterns of resilience’, Information, Communication & Society 26: 7, 2023, pp. 1342–62, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.2006744.

Keating and Schmitt, ‘Ideology and influence in the debate over Russian election interference’.

Francesco Giumelli, Fabian Hoffmann and Anna Książczaková, ‘The when, what, where and why of European Union sanctions’, European Security 30: 1, 2021, pp. 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1797685.

Council of the EU, ‘EU imposes sanctions on state-owned outlets RT/Russia Today and Sputnik's broadcasting in the EU’, 2 March 2022, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/03/02/eu-imposes-sanctions-on-state-owned-outlets-rtrussia-today-and-sputnik-s-broadcasting-in-the-eu.

These investigations resulted in the 2019 report released by special counsel Robert S. Mueller, III, the 2019 Justice Department inspector general report, a bipartisan report by the Senate Intelligence Committee issued in 2020 by a Republican-controlled Senate, and the 2023 report released by special counsel John Durham.

The White House, ‘Statement by the president on actions in response to Russian malicious cyber activity and harassment’, 29 Dec. 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/12/29/statement-president-actions-response-russian-malicious-cyber-activity.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Background to ‘Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections’: the analytic process and cyber incident attribution (Washington DC: Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2016), https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/ICA_2017_01.pdf.

Robert S. Mueller, III, Report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election, vol. I (Washington DC: US Department of Justice, 2019), pp. 1–5, https://www.justice.gov/archives/sco/file/1373816/dl.

John H. Durham, Report on matters related to intelligence activities and investigations arising out of the 2016 presidential campaigns (Washington DC: US Department of Justice, 2023), p. 252, https://www.justice.gov/storage/durhamreport.pdf.

Scott Jennings, ‘Mueller's report looks bad for Obama’, CNN Opinion, 23 April 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/04/19/opinions/mueller-report-obama-jennings/index.html.

United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Report on Russian active measures campaigns and interference in the 2016 U.S. election, vol. 3: U.S. government response to Russian activities (Washington DC: Select Committee on Intelligence, 2020), https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report_Volume3.pdf.

Philip Ewing, ‘Fact check: why didn't Obama stop Russia's election interference in 2016?’, NPR, 21 Feb. 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/02/21/587614043/fact-check-why-didnt-obama-stop-russia-s-election-interference-in-2016.

US Department of the Treasury, ‘Treasury sanctions Russian cyber actors for interference with the 2016 U.S. elections and malicious cyber-attacks’, 15 March 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0312.

‘Trump sides with Russia against FBI at Helsinki summit’, BBC News, 16 July 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-44852812.

Emma Ashford, ‘Strategies of restraint: remaking America's broken foreign policy’, Foreign Affairs, 24 Aug. 2021. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-08-24/strategies-restraint.

The White House, ‘Fact sheet: imposing costs for harmful foreign activities by the Russian government’, 15 April 2021, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/15/fact-sheet-imposing-costs-for-harmful-foreign-activities-by-the-russian-government; The White House, Executive Order 14024 of April 15, 2021. Blocking property with respect to specified harmful foreign activities of the government of the Russian Federation, 2021, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/19/2021-08098/blocking-property-with-respect-to-specified-harmful-foreign-activities-of-the-government-of-the.

The White House, Executive Order 14114 of December 22, 2023. Taking additional steps with respect to the Russian Federation's harmful activities, 2023, https://ofac.treasury.gov/media/932441/download?inline. Executive orders related to Russia's unprovoked war on Ukraine are a separate matter.

Emiliana De Blasio and Donatella Selva, ‘Who is responsible for disinformation? European approaches to social platforms' accountability in the post-truth era’, American Behavioral Scientist 65: 6, 2021, pp. 825–46, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221989784.

RonNell Andersen Jones and Lisa Grow Sun, ‘Repairing the damage: President Biden and the press’, University of Illinois Law Review, 30 April 2021, pp. 111–20, https://illinoislawreview.org/symposium/first-100-days-biden/repairing-the-damage.

Kate Martyr, ‘Russian disinformation mainly targets Germany: report’, Deutsche Welle, 3 Sept. 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/russian-disinformation-mainly-targets-germany-eu-report/a-56812164.

Bernhard Blumenau, ‘Breaking with convention? Zeitenwende and the traditional pillars of German foreign policy’, International Affairs 98: 6, 2022, pp. 1895–913, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiac166.

German Federal Returning Officer, ‘Bundestagswahl 2021: Erkennen und Bekämpfen von Desinformation’, 2021, https://www.bundeswahlleiterin.de/bundestagswahlen/2021/fakten-fakenews.html.

Julia Smirnova et al., Digitale Gewalt und Desinformation gegen Spitzenkandidat: innen vor der Bundestagswahl 2021 (Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2021), https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/digitale-gewalt-und-desinformation-gegen-spitzenkandidatinnen-vor-der-bundestagswahl-2021; Elsa Hedling ‘Gendered disinformation’, in Karin Aggestam and Jacqui True, eds, Feminist foreign policy analysis (Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2024).

Kate Brady, ‘Online trolls direct sexist hatred at Annalena Baerbock’, Deutsche Welle, 5 Oct. 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-annalena-baerbock-becomes-prime-target-of-sexist-hate-speech/a-57484498.

Mark Scott, ‘Russia sows distrust on social media ahead of German election’, Politico, 3 Sept. 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-russia-social-media-distrust-election-vladimir-putin.

Salome Giunashvili, ‘Who does the photo depict?—German foreign minister or Russian porn model?’, Myth Detector, 28 March 2023, https://mythdetector.com/en/who-does-the-photo-depict-german-foreign-minister-or-russian-porn-model/.

Thorsten Faas and Tristan Klingelhöfer, ‘German politics at the traffic light: new beginnings in the election of 2021’, West European Politics 45: 7, 2022, pp. 1506–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2045783.

Blumenau, ‘Breaking with convention?’.

Federal Government of Germany, ‘Russische Desinformationskampagnen: Wie aus Narrativen eine Desinformation wird’, 30 Aug. 2022, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/schwerpunkte/umgang-mit-desinformation/aus-narrativen-desinformation-2080112.

Kate Connelly, ‘Germany unearths pro-Russia disinformation campaign on X’, Guardian, 26 Jan. 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/26/germany-unearths-pro-russia-disinformation-campaign-on-x.

Euro News, ‘Germany recalls ambassador to Russia over hacker attack’, 7 May 2024, https://www.euronews.com/next/2024/05/07/germany-recalls-ambassador-to-russia-over-hacker-attack.

EU Commission, ‘Tackling coronavirus disinformation’, undated, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/coronavirus-response/fighting-disinformation/tackling-coronavirus-disinformation_en.

World Health Organization, ‘Infodemic’, undated, https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic.

James Pamment, The EU's role in fighting disinformation: taking back the initiative (Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020), https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2020/07/the-eus-role-in-fighting-disinformation-taking-back-the-initiative.

Gary Machado, Being cautious with attribution: foreign interference & COVID-19 disinformation (Brussels: EU DisinfoLab, 2020), https://www.disinfo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/20200414_foreignintereferencecovid19-1.pdf.

Pamment, The EU's role in fighting disinformation.

Ben Dubow, Edward Lucas and Jake Morris, ‘Jabbed in the back: mapping Russian and Chinese information operations during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Center for European Policy Analysis, 2 Dec. 2021, https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/jabbed-in-the-back-mapping-russian-and-chinese-information-operations-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.

‘The Kremlin and disinformation about coronavirus’, EUvsDisinfo, 16 March 2020, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/the-kremlin-and-disinformation-about-coronavirus.

Katarina Rebello et al., Covid-19 news and information from state-backed outlets targeting French, German and Spanish-speaking social media users (Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute, 2020), https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2020/06/Covid-19-Misinfo-Targeting-French-German-and-Spanish-Social-Media-Users-Final.pdf.

Rachel Schraer, ‘Covid: conspiracy and untruths drive Europe's Covid protests’, BBC News, 27 Nov. 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/59390968; ‘Vaccine fears spark conspiracy theories’, Deutsche Welle, 5 Dec. 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/in-germany-vaccine-fears-spark-conspiracy-theories/a-53419073.

‘Verordnungen zu neuen Corona-Regeln fehlen noch’, Nön, 30 April 2020, https://www.noen.at/in-ausland/fpoe-kritik-verordnungen-zu-neuen-corona-regeln-fehlen-noch-oesterreich-epidemie-verordnung-viruserkrankung-203510962; Maria Fiedler, ‘Mit voller Kraft gegen den Lockdown: wie die AfD versucht, aus dem Corona-Tief zu kommen’, Tagesspiegel, 8 May 2020, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/wie-die-afd-versucht-aus-dem-corona-tief-zu-kommen-6865738.html.

Ben Knight, ‘“Extremists and terrorists don't go into lockdown”’, Deutsche Welle, 15 June 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/pandemic-spurred-extremism-says-german-domestic-intelligence/a-57906728.

EUvsDisinfo, ‘EEAS special reports’, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/eeas-special-reports.

EUvsDisinfo, EEAS special report update: short assessment of narratives and disinformation around the COVID-19 pandemic (EUvsDisinfo, 2021), https://euvsdisinfo.eu/eeas-special-report-update-short-assessment-of-narratives-and-disinformation-around-the-covid-19-pandemic-update-december-2020-april-2021.

EUvsDisinfo, EEAS special report update.

EUvsDisinfo, EEAS special report update.

Josep Borrell, ‘Disinformation around the coronavirus pandemic’, opening statement at the European Parliament, 30 April 2020, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/disinformation-around-coronavirus-pandemic-opening-statement-hrvp-josep-borrell-european-parliament.

‘EU pressured to give results of leak probe into China disinformation’, Financial Times, 20 July 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/5a323cec-82a6-4e64-9bbb-27e8de7b9929.

Borrell, ‘Disinformation around the coronavirus pandemic’.

Mario Esteban et al., eds, Europe in the face of US–China rivalry (Madrid: European Think-tank Network on China, 2020), p. 179.

Machado, Being cautious with attribution.

Machado, Being cautious with attribution.

Author notes

The authors are listed in alphabetical order and contributed equally to this article. An earlier version of this article was presented at a research seminar at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs, and we thank the participants for their feedback. We would also like to thank the International Affairs editorial team and the anonymous reviewers. This research was supported by the Psychological Defence Research Institute at Lund University. Elsa Hedling's research was also supported by the Swedish Research Council-funded project ‘Postdigital propaganda’ (2022-05414) and Hedvig Ördén's research by IntelHub—a project funded by the Carlsberg foundation.