-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Birgitta Niklasson, Katarzyna Jezierska, The politicization of diplomacy: a comparative study of ambassador appointments, International Affairs, Volume 100, Issue 4, July 2024, Pages 1653–1673, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiae116

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A politicization of diplomacy weakens the professionalism of the foreign service and arguably endangers the external relations of states. Yet, this phenomenon has largely escaped scholarly scrutiny. Public administration research on politicization usually overlooks the foreign service, whereas diplomacy scholars have focused almost exclusively on the United States. Our exploratory study of ambassador appointments compares the levels and modes of politicization (through politically connected professionals, or political appointees) of 669 ambassadors in 2019, across seven countries and three administrative traditions. The analysis is guided by three expectations: 1) countries that are more politicized overall appoint more non-career ambassadors; 2) patronage recruitment of political appointees focuses on low-hardship postings; and 3) politically connected professionals are used to control politically important foreign missions. We find that states politicize their foreign services to a varied degree and in different ways. Appointing politically connected professionals instead of political appointees is the most common way of politicization among our cases. In this regard, the US is an outlier, which also points to the need of studying politicization of diplomacy comparatively. This article thus makes an important contribution by setting the agenda for future research on this hitherto underexplored topic.

Joe Biden is sticking to tradition as he slowly fills the vacancies in the ranks of ambassadors across the world, focussing on mixing longtime career diplomatic officials with figures with strong ties to himself and the Democratic party. Among Biden's expected picks is Caroline Kennedy, former US ambassador to Japan, daughter of the former president, and longtime Biden friend, ally and donor, to be ambassador to Australia.

—Daniel Strauss, the Guardian1

Daniel Strauss, the above-quoted political reporter for the Guardian, shows no surprise that ambassadors are appointed on the basis of such merits as being a ‘friend’ or a ‘donor’. Such practices are framed as ‘tradition’ despite an undertone of disappointment: ‘Progressives had hoped for fewer Biden allies, more foreign service professionals’, as his article's lead paragraph runs. Indeed, concerns about the growing politicization of prestigious diplomatic positions in both strong and faltering democracies are a recurring theme in public debates2 as well as in research publications.3 Press articles reporting misconduct and a lack of competence among politically appointed diplomats abound. For instance, David Cornstein, who served as a Donald Trump-nominated ambassador to Hungary, was criticized for being ‘dangerously unprepared for the job’4 and for expressing positions contrary to US policy, thus undermining the work of other diplomats. Given the wide and critical attention given to the politicization of diplomacy, it is surprising that few scholars have systematically studied this phenomenon.

The aim of this article is to fill this gap. We bring together the scarce diplomacy literature on the politicization of recruitment, which has focused almost exclusively on the US, and the public administration literature, which has a long tradition of studying politicization but has omitted ministries of foreign affairs (MFAs). Our article systematically and comparatively studies the appointments of ambassadors as a case of politico-administrative relations. More specifically, we investigate the patterns of recruitment of ambassadors based on political rather than professional merits. We explore how and to what extent diplomatic appointments are politicized across countries with different administrative traditions.

Although the appointments and careers of the great majority of diplomats in liberal democracies are not politicized,5 we need more knowledge about how and where diplomacy is politicized.6 Public administration scholars have long argued that politicized recruitment of civil servants poses a threat to the quality, stability and legitimacy of government.7 This kind of recruitment also sidelines the profession, contributing to its devaluation and disincentivizing the development of expertise through a civil service career.8

Ambassadors are elite government actors9 who are highly visible in their representative role as heads of missions abroad, i.e. embassies.10 These missions are a central institution of MFAs, which are among the oldest, largest and most prestigious of ministries worldwide.11 Embassies and ambassadors address high-profile policy issues such as security, trade and aid. Evidence has shown that the sheer presence of a diplomatic mission in a country increases exports12 and trade flows,13 and reduces trade volatility.14 Furthermore, diplomacy is commonly considered a tool for avoiding or limiting the use of force and warfare in international relations.15 Ambassadors thus play a pivotal role in the external relations and foreign policies of states. Studies in international relations in general, even beyond diplomatic studies, would therefore benefit from paying greater attention to ambassadors. Who these people are and how they are recruited are politically as well as symbolically important questions to pursue.

Our comparative investigation of the politicization of MFAs in different country contexts is the first study of this sort. The focus is mainly on data generation and exploratory analysis of variations among countries rather than on hypothesis confirmation, even though our empirical exploration is guided by expectations derived from previous research. The data consisted of the professional backgrounds of 669 ambassadors representing seven countries (Denmark, Iceland, Mexico, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States) in 2019. We study the extent to which ambassadorial appointments are made on political rather than meritocratic criteria and assess where different kinds of ambassadors are posted. In conversation with prior research on diplomacy and public administration, we formulate three expectations for which countries are the most likely to politicize and what kinds of postings are made. Determining causality and identifying specific causal mechanisms are beyond the scope of this article, due to our limited empirical data. Rather, we view this study as setting the agenda for future research in the field of diplomacy politicization. We observe interesting patterns in the way in which different states politicize ambassador appointments that call for further comparisons across time and space. In the following sections, we provide a short overview of politicization in diplomatic studies and prior public administration scholarship. Based on these strands of research, in the subsequent sections we distinguish three types of diplomatic recruitment and formulate three expectations of the politicization of diplomacy that guide our empirical analysis.

Diplomatic studies and politicization

Historically, as MFAs were professionalized in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, states developed permanent diplomatic corps, limiting nominations made on other grounds such as wealth and family connections.16 This was motivated by a move from amateurism to professionalism in foreign service. Highly competitive entry exams for foreign service were introduced, fostering the diplomatic profession and a strong esprit de corps among diplomats. Today's career diplomats are subject to separate recruitment, training, and career structures, setting them apart from the rest of the civil service.17

The reason for this training is that the work of an ambassador—the highest-ranking diplomat—is quite demanding. The primary responsibilities of diplomats are representing and protecting the interests and citizens of their home state abroad, initiating and facilitating strategic agreements, negotiating treaties and conventions, exchanging information, fostering trade and commerce, and pursuing friendly international relations.18 To succeed in these tasks, ambassadors build relationships with a broad range of actors, such as diplomats from other states; political, economic and cultural elites of the host state; and local civil society actors. Networking is a crucial tool in the diplomatic repertoire.19

Ambassadors are also expected to have a specific set of competencies and skills, such as expertise in languages, countries or regions and functional expertise in areas such as economics and international law.20 During professional diplomatic training, they gain knowledge about diplomatic norms such as etiquette, dress codes and order of precedence. Diplomats must showcase a high degree of flexibility and an intuitive sensitivity for the social game of the varied contexts in which they appear, knowing the rules as well as when to break them.21

Given that such skills and competences take years to develop, it follows that most MFAs are dominated by career ambassadors who have gone through the MFA ranks and/or are diplomatic academy graduates. Nevertheless, most countries apply a mixed system of appointing ambassadors, leaving political principals the possibility of appointing some non-career ambassadors.22 These ambassadors belong to the diplomatic corps of a state, similar to career diplomats;23 they serve the same functions and enjoy the same diplomatic immunity under international law, but they have been shown to possess lower qualifications and perform less highly than career diplomats.24 On average, the performance score of political appointees is 10 per cent lower, as measured by the quality of political reporting.25

Indeed, one might wonder why non-career diplomats are appointed at all. One reason, based on the US example, is patronage, i.e. as a reward for party loyalty. Major presidential campaign donors and other actors politically connected to newly elected presidents are rewarded with diplomatic positions.26 These prestigious posts can also be used to control foreign policy implementation.27 Diplomacy is nearly always conducted by relatively autonomous agents. ‘Ambassadors operate far from home with inherently limited oversight’,28 which may increase the propensity of political leaders to try to control foreign policy implementation through the appointment of loyal people.29

The number of ambassadors appointed politically is regulated by legislation and praxis and is likely to differ among countries. Previous research has focused on the US, perhaps because of the blatant politicization of ambassadorial postings in this context, illustrated by the opening quotation. Since the second half of the twentieth century, the proportion of US ambassadorial appointments has fluctuated around a ratio of 70 per cent career diplomats to 30 per cent political appointments.30 Reportedly, the rates of political appointments are relatively high for foreign services compared to other US government agencies. However, we know little about the politicization of diplomacy beyond the US case. The studies by Rolando Stein31 and Matthias Erlandsen et al.32 indicate that there is considerable variation regarding this phenomenon that remains to be mapped and accounted for.

Politicization in public administration scholarship

Although the politicization of MFAs has largely been overlooked in diplomatic studies, the politicization of civil servants has been widely studied in other areas of government,33 for example in ministries,34 local city management,35 regulatory agencies36 and other types of government agency.37 Politicization is a major theme in public administration scholarship. The term ‘politicization’ refers to a variety of practices that seek to favourably influence different arenas of decision-making to steer the final outcome towards a political objective.38 Politicization is usually contrasted with the Weberian ideal of modern bureaucracy and is seen as devaluing the professional competences of civil servants and the overall quality of public administration and democracy.39

Scholars have striven to tease out the contexts in which public agencies are more likely to become politicized and why. The relevance of administrative traditions in western democracies is sometimes mentioned.40 Made up of enduring informal and formal institutions based on values and structures, these traditions frame the relationship between the political elite and the civil service.41 Administrative traditions are often categorized as Anglo-American, Napoleonic, German, Scandinavian and sometimes Asian.42

While helpful in estimating the overall level of politicization of different countries' public services, administrative traditions cannot be expected to capture the full variation in specific parts of administrative systems. Prior research has demonstrated that public agencies vary greatly in terms of tasks, political salience and policy/management/implementation autonomy,43 and that such variations influence politicians' wishes to control the appointments of agency heads.44 MFAs are public agencies, but differ significantly in some respects from other branches of the civil service. Distinctive MFA traits, such as a high degree of autonomy and professionalism, warrant caution in assuming that previous general knowledge about public administrations writ large automatically applies to this particular branch of government.

However, foreign services are usually not within the purview of public administration scholars. Our study therefore provides important theoretical and empirical insights into politico-administrative relations by exploring how the politicization of diplomacy varies among countries and whether the pattern follows or diverges from what we know about different administrative systems in general. These insights also contribute to an understanding of how politicization plays into, and may be driven by, interstate relations.

Three types of recruitment

While public administration scholars have developed several subtypes of politicization practices, a common conceptualization outlines the systems and criteria under which officials, particularly senior officials, are recruited. Such formal or direct politicization is the focus of this study. It amounts to political control over the selection of civil servants45 and hence indicates a departure from the application of merit criteria in recruitment.46

The binary distinction between politicized and merit-based appointments can be blurred, however. As the introductory quotation demonstrated, politically motivated appointments do not necessarily result in the selection of individuals who lack relevant competences. Caroline Kennedy was not only a ‘longtime Biden friend, ally and donor’, but also a ‘former US ambassador to Japan’.47 Moreover, qualifications other than diplomatic training, such as political experience48 or an NGO background,49 are arguably useful for ambassadors. Indeed, in the public administration literature, a trend of appointing ‘politically connected professionals’50 has been noted. These nominees are often recruited from outside the party and are qualified enough to justify their appointment on merit; however, they are also ideologically like-minded, possessing ‘the right sorts of sensitivities for those jobs to be done well’.51

Hence, in addition to singling out career diplomats and those who are politically appointed, which is the standard approach in diplomatic studies, we also distinguish politically connected professionals in our analysis. We interpret appointments of politically connected professionals as a less overt kind of politicization—that recognizes the particular competences associated with the diplomatic profession—contrary to political appointments of people with no diplomatic background. This tripartite categorization allows us to nuance the discussion on politicization in diplomacy.

Expectations of politicization in diplomacy

Tradition: The first expectation is that countries in which public administration systems are more politicized overall will also have a greater share of non-career ambassadors (politically appointed or politically connected professionals).

As discussed previously, scholars use administrative traditions as explanations for overall levels of politicization in the bureaucracies of states. The German and Napoleonic traditions are generally described as more politicized than the Anglo-American and Scandinavian traditions. However, there is plenty of variation between countries that follow the same administrative tradition. For instance, the public administration of Iceland is characterized by clientelism and patronage to a greater degree than that of other Scandinavian countries,52 such as Denmark.53 In the Anglo-American tradition, on the other hand, US public administration is more politicized than the British model,54 and in the Napoleonic tradition, that of Mexico is more politicized than that of Spain.55

Since MFAs have largely been omitted from politicization studies and diplomacy scholars have focused almost exclusively on the politicization of US ambassadorial appointments, we explore whether MFAs follow the pattern indicated by administrative traditions. The answer is not given. As noted above, the autonomy and high prestige of MFAs may supersede these traditions, but for want of better options, we argue that administrative traditions provide a reasonable guess.

Patronage: The second expectation is that political appointees are more frequently sent to desirable posts characterized by a low level of hardship.

The second expectation is related to ambassadorships as a means of rewarding party loyalty. The prospect of leading a glamorous life as a high-status figure in a fashionable metropolitan city may induce considerable campaign funding.56 However, not all foreign missions are likely to have the same appeal as rewards. The level of hardship associated with a mission is sometimes high, particularly in places with challenging local conditions of safety and security, health care, education and climate. Previous studies of US postings have revealed that political appointees are more likely to be sent to countries with a low level of hardship, e.g. high-income, high-tourism western European capitals.57

Control: The third expectation is that politically connected professionals are more often appointed to capitals of great political importance (indicated by the presence of many foreign missions or by being located in the same region as the sending state).

Another reason for choosing non-career diplomats is to control foreign policy implementation. If political principals are interested in results, however, it would make sense to appoint somebody who is not just loyal but who also possesses the right kind of competence for the job, i.e., a politically connected professional, particularly with respect to appointments to important foreign missions. While the number of foreign missions varies depending on the resources of the sending state, all sending states prioritize where they will establish embassies based on their assessment of the relevance of diplomatic relations with the receiving state.

For instance, in 2019 Washington DC hosted 181 ambassadors and Reykjavik hosted 14. The number of foreign missions can be used as an indicator of the political importance of a state.58 We contend that politically important postings are more frequently assigned to politically connected professionals, particularly since these foreign missions are also likely to have more resources.59 If the mission is large, the appointment of a non-career diplomat may be less risky, because there is a professional deputy head of mission and several diplomats who can assist the inexperienced ambassador.60

The total number of foreign missions in a state captures its importance only in a general sense. Another way of apprehending the political importance of a receiving state is through the political, economic and cultural proximity between the two. Countries usually emphasize diplomatic relations with their regional neighbours more strongly than they do relations with geographically distant states.61

Methodology

Case selection and data

Our sample spans three different administrative traditions: the Scandinavian (Denmark, Iceland and Sweden), the Anglo-American (the UK and US) and the Napoleonic (Mexico and Spain).62 The selection of countries was guided by their relatively low/high ranking on the professionalization scale within their specific administrative tradition.63 We selected countries with a parliamentary and a presidential system in each tradition, since previous research has found that presidential systems are more politicized.64 Ideally, we would have liked to cover all administrative traditions and a greater number of cases from each, but the demanding data collection processes—involving manual coding of ambassadors' professional backgrounds in five different languages—did not allow for this. We therefore aimed to include a broad span of politicization levels within the selected administrative traditions; the cases are thus intended not to be representative, but rather to capture variation in the politicization of diplomacy within the different administrative traditions. As this is the first attempt to systematically compare the level of politicization of diplomacy among administrative traditions, we believe that insights from this limited sample can still make a substantial research contribution.

While we acknowledge that politicization can occur at all levels of the civil service, we focus on the top echelons of diplomacy, i.e., ambassadors. Previous research has identified ambassador postings as particularly susceptible to politicization,65 and these are the appointments over which politicians might have some discretionary power.66 We relied on the GenDip dataset67 for the full list of ambassadors in our selected cases in 2019. We considered only the main posting of each ambassador, disregarding side accreditations, which means that each ambassador was counted only once. Based on this list, we searched for information about the professional backgrounds of these 669 ambassadors,68 resorting to the respective MFA websites, local online news articles, and the ambassadors' CVs. The majority of our data were cross-coded by two different coders to increase reliability.

Operationalizations

In this section, we describe the variables included in our analyses. More details can be found in the online appendix.69

Professional background The diplomat's professional background was coded based primarily on their position immediately before their appointment to the ambassadorship in 2019. This experience determined whether an ambassador was coded as a career diplomat or a non-career diplomat (politically connected professional or political appointee). Career diplomats are those who are recruited directly from the relevant country's foreign service. The great majority of these ambassadors have a professional background within the MFA; they have followed a particular diplomatic training programme and/or pursued an official career trajectory within the diplomatic profession.70

In the case of non-career diplomats, we also searched for relevant diplomatic experiences earlier in their career to decide whether an ambassador should be coded as a politically connected professional or a political appointee. Political appointees are ambassadors who are recruited from a position external to the MFA and who lack previous diplomatic experience and training. They may receive a diplomatic ‘crash course’ after being appointed, but that kind of post-recruitment training is not considered here. Politically connected professionals, on the other hand, combine the characteristics of career diplomats and political appointees; they are recruited externally, e.g., from politics, other ministries, business or civil society, but have prior relevant diplomatic experience and/or training.

Hardship postings Hardship is associated with difficult living conditions, unhealthy environments and the prevalence of political violence. Although MFAs may assess the hardship level of a particular posting differently, we have no reason to believe that these assessments vary greatly. We therefore used the hardship codes of the US State Department, since the US is one of the countries with the largest number of diplomatic representations abroad, and its codes are easily accessible and relatively detailed. The hardship variable is normalized in our analyses so that 0 signifies no hardship and 1 signifies the highest level of hardship.

Politically important postings We formed our assessment of the political importance of a particular posting to the sending state in two distinct ways. First, we calculated the number of foreign ambassadors in the capital of the receiving state. The higher the number was, the higher the ranking given, which implies high diplomatic and political clout.71 The highest ranked posting is coded 1, the second highest 2, etc. The receiving states were also grouped into quintiles based on the share of ambassadors received. Those who received the lowest share of ambassadors were placed in group 5, and those with the highest share were placed in group 1. Second, we treated shared regional location as another indication of political importance to the sending state.72

Analysing patterns in the politicization of diplomacy

Below, we analyse the extent and ways of politicizing ambassador appointments in our sample. We systematically trace the prevalence of non-career ambassadors (political appointees and politically connected professionals) and where they were posted. This empirical exploration is guided by the three expectations presented above.

Politicization in different administrative traditions

Most (82%) of the ambassadors included in this study were career diplomats (see table 1), which confirms observations from previous studies.73 Politicized recruits (politically connected professionals and political appointees) usually came from other parts of the public service (8%), politics (4%), or private and voluntary sectors (6%), for a total of 18 per cent. The appointment of civil servants from outside the MFAs was the most common type of recruitment in all countries except Sweden and the US. In Sweden, the share of ambassadors recruited from the political sphere was equally large (5%), whereas the most common kind of politicized recruitment in the US was from the private and voluntary spheres (22%).

| Sender . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | Total, all groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | 95 | 5 | 0 | 100 (21) |

| Denmark | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (66) |

| Spain | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (115) |

| Sweden | 87 | 10 | 3 | 100 (96) |

| UK | 86 | 10 | 4 | 100 (157) |

| Mexico | 83 | 8 | 9 | 100 (76) |

| US | 65 | 2 | 33 | 100 (138) |

| All countries | 82 (549) | 8 (55) | 10 (65) | 100 (669) |

| Sender . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | Total, all groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | 95 | 5 | 0 | 100 (21) |

| Denmark | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (66) |

| Spain | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (115) |

| Sweden | 87 | 10 | 3 | 100 (96) |

| UK | 86 | 10 | 4 | 100 (157) |

| Mexico | 83 | 8 | 9 | 100 (76) |

| US | 65 | 2 | 33 | 100 (138) |

| All countries | 82 (549) | 8 (55) | 10 (65) | 100 (669) |

Source: Authors’ research

Note: Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies.

| Sender . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | Total, all groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | 95 | 5 | 0 | 100 (21) |

| Denmark | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (66) |

| Spain | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (115) |

| Sweden | 87 | 10 | 3 | 100 (96) |

| UK | 86 | 10 | 4 | 100 (157) |

| Mexico | 83 | 8 | 9 | 100 (76) |

| US | 65 | 2 | 33 | 100 (138) |

| All countries | 82 (549) | 8 (55) | 10 (65) | 100 (669) |

| Sender . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | Total, all groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | 95 | 5 | 0 | 100 (21) |

| Denmark | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (66) |

| Spain | 88 | 11 | 1 | 100 (115) |

| Sweden | 87 | 10 | 3 | 100 (96) |

| UK | 86 | 10 | 4 | 100 (157) |

| Mexico | 83 | 8 | 9 | 100 (76) |

| US | 65 | 2 | 33 | 100 (138) |

| All countries | 82 (549) | 8 (55) | 10 (65) | 100 (669) |

Source: Authors’ research

Note: Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies.

Our first expectation was that countries with more politicized civil services in general would appoint greater shares of political appointees and politically connected professionals. We know from previous studies that the US central government is more politicized than the governments of other states of the Anglo-American administrative tradition,74 with approximately 30 per cent of US ambassadors being recruited from outside the US Foreign Service.75 As table 1 shows, our study confirmed this pattern, which also serves as a reliability check of our results.

Among our cases, the US clearly stands out for appointing only 65 per cent of career diplomats. The next lowest share in career diplomat appointments (83%), is that of Mexico, which does not differ greatly from the shares of the UK, Sweden, Spain or Denmark (86–88%). However, nearly all of Iceland's ambassadors (95%) were career diplomats. Thus, we observed that the politicization of diplomacy did not clearly follow the traditional pattern of these public administrations. Contrary to our expectation, there were only small differences between cases representing different administrative traditions—and between cases within the same tradition.

First, we expected Mexico and Spain, which represent the Napoleonic administrative tradition, to stand out as the most politicized cases. While Mexico had the second most politicized diplomatic corps in our sample, it came nowhere near the US on this measure. On the other hand, the Scandinavian countries received, on average, a higher score for career recruitment than did the two Napoleonic countries, which was in line with our expectations, but the differences were small.

Second, the variation within the three traditions did not consistently follow our expectations. The difference between the UK and the US within the Anglo-American tradition was as expected. US ambassadors were clearly more politicized than British ambassadors. Not only did US presidents recruit a greater share of ambassadors from outside the MFA, but almost all non-career US ambassadors came directly from other areas and had no diplomatic experience (33% out of 35%). Additionally, there was a slightly lower share of career diplomats among Mexican ambassadors than among Spanish ambassadors, in line with the expectation of variation in the Napoleonic tradition. Among the Scandinavian states, however, Iceland had the highest share of career diplomats, even though it had been identified as having the most politicized public administration among the Scandinavian countries.76 Admittedly, Iceland has a small foreign service, so just one or two external recruits would bring the share of non-career ambassadors to the same level as that of the two Scandinavian neighbours. However, based on our data, there were no signs that Icelandic ambassadors were more politicized than other ambassadors from the same administrative tradition. Moreover, none of the politicized ambassadors of Iceland were political appointees; they were all politically connected professionals, which means that in 2019, no Icelandic ambassador completely lacked relevant diplomatic experience.

In summary, the patterns we observed were partly in line with our expectation that administrative traditions matter. The comparisons between and within traditions were ambiguous. However, our results clearly highlight the importance of the category of politically connected professionals in studies of diplomacy. Recruiting external ambassadors with relevant diplomatic experience appears to be the most common way of politicizing ambassador appointments in all states included in our sample, except the US and Mexico.

Politicization as patronage

We now trace where the different categories of ambassadors were posted to determine whether the politicization of diplomacy might be motivated by patronage. Our second expectation was that political appointees would more frequently be appointed to desirable postings characterized by a low level of hardship, i.e., comfortable and safe living conditions.77 The assumption was that when party supporters with no previous diplomatic experience are granted ambassadorships as an expression of patronage, they are likely to be sent to plum postings, i.e., desirable places with good conditions (otherwise, the appointment might not be perceived as a reward).

Table 2 compares the average hardship level at the postings of different kinds of ambassadors. Overall, career diplomats scored higher on hardship (0.404) than the other two ambassador categories. This difference was statistically significant, indicating that career diplomats were more frequently sent to countries where living conditions are harsh because of poverty, military conflict, extreme climate and so on. The pattern for political appointees was the opposite—their average hardship score was only 0.225. This score was significantly lower than that of the other two categories of ambassador (0.399).78

Average hardship level of the postings to which ambassadors of different professional backgrounds are sent

| Professional background . | Average hardship level . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 0.404 (538) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.276 (112) | +0.128** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 0.341 (49) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 0.385 (601) | −0.044 |

| Political appointees (a) | 0.225 (63) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.399 (587) | −0.174** |

| Professional background . | Average hardship level . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 0.404 (538) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.276 (112) | +0.128** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 0.341 (49) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 0.385 (601) | −0.044 |

| Political appointees (a) | 0.225 (63) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.399 (587) | −0.174** |

Source: Authors’ research

Note: The minimum level of hardship is 0, and the maximum level is 1.

**p<.001.79 Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies. N=650, as hardship level is missing for 19 cases.

Average hardship level of the postings to which ambassadors of different professional backgrounds are sent

| Professional background . | Average hardship level . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 0.404 (538) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.276 (112) | +0.128** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 0.341 (49) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 0.385 (601) | −0.044 |

| Political appointees (a) | 0.225 (63) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.399 (587) | −0.174** |

| Professional background . | Average hardship level . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 0.404 (538) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.276 (112) | +0.128** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 0.341 (49) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 0.385 (601) | −0.044 |

| Political appointees (a) | 0.225 (63) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 0.399 (587) | −0.174** |

Source: Authors’ research

Note: The minimum level of hardship is 0, and the maximum level is 1.

**p<.001.79 Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies. N=650, as hardship level is missing for 19 cases.

Since the absolute number of politically connected professionals and political appointees from each individual sending state was low, it is difficult to determine the extent to which differences in hardship level applied within each country context. For instance, five of seven Mexican political appointees were posted in Latin American countries with fairly high levels of hardship (0.43–1.00), and the only Danish political appointee was stationed in Burkina Faso (hardship level 0.71). However, none of the three Swedish political appointees were sent to a country with a hardship level higher than 0.14 (Canada, Chile and Iceland), and both the UK and the US appeared reluctant to post political appointees to hardship countries.

Thus, our second expectation about the politicization of ambassador appointments as an expression of patronage received some support. Overall, our results indicate that ambassador appointments are used as a reward primarily in the two Anglo-American countries and perhaps in Sweden. In the other countries, political appointees appeared to be sent to hardship postings to the same extent as career diplomats and politically connected professionals.

Politicization as control

The third expectation concerned the recruitment of politically connected professionals as a means of increasing political control over particularly important diplomatic missions. To determine whether this was the case, we first considered the overall political importance of the states to which different categories of ambassadors were sent.

The ten highest-ranked countries according to the number of embassies hosted in their capitals in 2019 were the US, Belgium (the administrative centre of the European Union), the UK, Germany, India, Italy, Switzerland, Brazil, China and France. It is therefore not surprising that the results in table 3 resemble those in table 2, since the hardship levels and rankings of receiving countries overlapped somewhat.81

Average ranking of the receiving states to which ambassadors of different professional backgrounds are sent

| Professional background . | Average ranking of receiving state . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 70.56 (549) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 60.03 (129) | +10.53** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 62.38 (55) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 69.23 (614) | -6.85 |

| Political appointees (a) | 58.03 (65) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 69.81 (604) | −11.78* |

| Professional background . | Average ranking of receiving state . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 70.56 (549) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 60.03 (129) | +10.53** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 62.38 (55) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 69.23 (614) | -6.85 |

| Political appointees (a) | 58.03 (65) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 69.81 (604) | −11.78* |

Source: Authors’ research

Note: *p<.1, **p<.05.80 N=669. Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies. Low figures imply high rank, i.e. the highest-ranked country (US) is ranked 1, the second highest-ranked country (Belgium) is 2, and the lowest-ranked country (Palau) is ranked 195.

Average ranking of the receiving states to which ambassadors of different professional backgrounds are sent

| Professional background . | Average ranking of receiving state . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 70.56 (549) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 60.03 (129) | +10.53** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 62.38 (55) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 69.23 (614) | -6.85 |

| Political appointees (a) | 58.03 (65) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 69.81 (604) | −11.78* |

| Professional background . | Average ranking of receiving state . | Difference (a-b) . |

|---|---|---|

| Career diplomats (a) | 70.56 (549) | |

| Political appointees and politically connected professionals (b) | 60.03 (129) | +10.53** |

| Politically connected professionals (a) | 62.38 (55) | |

| Career diplomats and political appointees (b) | 69.23 (614) | -6.85 |

| Political appointees (a) | 58.03 (65) | |

| Career diplomats and politically connected professionals (b) | 69.81 (604) | −11.78* |

Source: Authors’ research

Note: *p<.1, **p<.05.80 N=669. Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies. Low figures imply high rank, i.e. the highest-ranked country (US) is ranked 1, the second highest-ranked country (Belgium) is 2, and the lowest-ranked country (Palau) is ranked 195.

Our expectation that politically significant postings would tend to be politicized by the appointment of politically connected professionals received only partial support. Politically connected professionals were indeed posted to countries of greater political importance; the average rank of their postings was 62.38, compared to 69.23 for ambassadors from other categories, but the difference was not statistically significant. We did observe a statistically significant difference between political appointees and other kinds of ambassadors, however; political appointees were also posted in relatively highly-ranked states. Their rank average was 58.03, compared to 69.81 for the others, but this difference was driven by the Anglo-American states. In all other countries, political appointees were actually more likely to be sent to lower-ranked states.

We also divided the receiving countries into quintiles based on the number of ambassadors received (table 4). Group 1 included the top 23 receiving countries. These were the countries that hosted the greatest number of foreign missions in 2019, and we assumed that they were the most important to the political leaders of the sending states. The expected pattern was the clearest in the extreme categories: groups 1 and 5. It was more common for politically connected professionals (26%) and political appointees (29%) than for career diplomats (19%) to be appointed to countries in group 1. In contrast, career diplomats were more likely to be sent to countries in group 5 (22%), which was also the least likely type of posting for non-career ambassadors.

Share (percentage) of ambassadors of different professional backgrounds in receiving states of various ranks

| Groups of receiving states . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | All groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: ranks 1–23 | 19 | 26 | 29 | 21 (137) |

| Group 2: ranks 24–46 | 19 | 18 | 23 | 20 (131) |

| Group 3: ranks 47–76 | 21 | 24 | 15 | 21 (137) |

| Group 4: ranks 77–113 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 20 (132) |

| Group 5: ranks 114–195 | 22 | 11 | 12 | 20 (132) |

| All countries | 100 (549) | 100 (55) | 100 (65) | 100 (669) |

| Groups of receiving states . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | All groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: ranks 1–23 | 19 | 26 | 29 | 21 (137) |

| Group 2: ranks 24–46 | 19 | 18 | 23 | 20 (131) |

| Group 3: ranks 47–76 | 21 | 24 | 15 | 21 (137) |

| Group 4: ranks 77–113 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 20 (132) |

| Group 5: ranks 114–195 | 22 | 11 | 12 | 20 (132) |

| All countries | 100 (549) | 100 (55) | 100 (65) | 100 (669) |

Source: Authors’ research.

Note: p=0.00882 (Kendall's tau-c). Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies. The fact that the colums do not add up to 100% is due to rounding errors.

Share (percentage) of ambassadors of different professional backgrounds in receiving states of various ranks

| Groups of receiving states . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | All groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: ranks 1–23 | 19 | 26 | 29 | 21 (137) |

| Group 2: ranks 24–46 | 19 | 18 | 23 | 20 (131) |

| Group 3: ranks 47–76 | 21 | 24 | 15 | 21 (137) |

| Group 4: ranks 77–113 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 20 (132) |

| Group 5: ranks 114–195 | 22 | 11 | 12 | 20 (132) |

| All countries | 100 (549) | 100 (55) | 100 (65) | 100 (669) |

| Groups of receiving states . | Career diplomats . | Politically connected professionals . | Political appointees . | All groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: ranks 1–23 | 19 | 26 | 29 | 21 (137) |

| Group 2: ranks 24–46 | 19 | 18 | 23 | 20 (131) |

| Group 3: ranks 47–76 | 21 | 24 | 15 | 21 (137) |

| Group 4: ranks 77–113 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 20 (132) |

| Group 5: ranks 114–195 | 22 | 11 | 12 | 20 (132) |

| All countries | 100 (549) | 100 (55) | 100 (65) | 100 (669) |

Source: Authors’ research.

Note: p=0.00882 (Kendall's tau-c). Numbers in parentheses represent frequencies. The fact that the colums do not add up to 100% is due to rounding errors.

Moving beyond the general political rank of receiving states, the perceived importance of receiving states is likely to differ among sending states depending on their geographical placement, cultural heritage and trade flows.83 Hence, we also checked whether politically connected professionals were more frequently posted to regions close to home, which were assumed to be generally more politically important to the sending state.

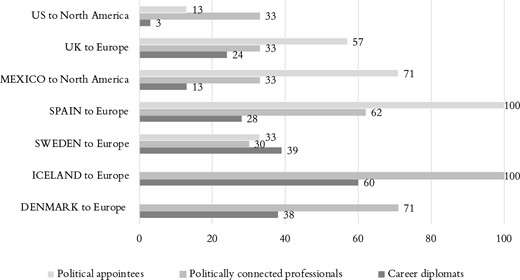

The number of cases in figure 1 is so low that we cannot say for certain, but the figures imply that politically connected professionals were largely posted to states in the region close to home. All countries included in our sample sent their politically connected professionals to their home region to a greater extent than to any other region in the world. Mexico, which is a part of North America, sent an equally large share to the neighbouring region of South America (33%), which can also be claimed to be politically, economically, and culturally close to Mexico. One of the politically connected US professionals (33%) was posted to Turkey, a geographically distant military ally. Sweden's appointment of three (30%) of its politically connected professionals to Africa perhaps made less sense in light of our theoretical expectation, but the same share of Swedish politically connected professionals was sent to Europe.

Share (percentage) of ambassadors of different professional backgrounds whom sending states (in caps) post in their home region

The overall picture was the same for political appointees; the political appointees of all countries, except Denmark and the US, were the most likely to be posted to the home region. The only Danish political appointee was posted to Burkina Faso, and the majority of American political appointees were sent to Europe. The latter exception can be interpreted as being in line with the control expectation, since the US has vital political, military, economic and cultural bonds to many European states. However, this may also be an expression of patronage, as the level of hardship in these European countries is low.

In summary, the results indicate that the third expectation regarding the appointment of politically connected professionals to important postings may be correct. This group of ambassadors in the sample was so small that it was difficult to determine the stability of the observed pattern. Furthermore, political appointees also appeared to be sent to postings with political clout, which implies that governments, particularly Anglo-American ones, may try to control the work of foreign missions at these postings without believing that the diplomatic experience of the ambassador is relevant to the successful implementation of foreign policy.

Concluding discussion

The primary aim of this study was to map how and to what extent ambassador appointments are politicized across seven countries belonging to three administrative traditions. In conducting the study, we bring together diplomacy scholarship and the public administration literature in a novel comparative exploration of the politicization of diplomacy. We hope that it will launch a conversation between these two scholarly fields. MFAs as institutions have recently attracted renewed interest,84 but surprisingly, these studies have not approached MFAs from a public administration perspective, leaving issues such as politicization, bureaucratic accountability85 and diplomatic discretion largely unexplored. We believe that cross-fertilization would benefit both fields.

While the distinction between meritocratic and politicized recruitment has already been discussed in diplomacy scholarship and among practitioners, we claim that this binary distinction should be nuanced. Inspired by the public administration literature, we introduce a third category, ‘politically connected professionals’, which combines party loyalty with diplomatic competence. This kind of external recruitment seems to be the dominant way in which most of the countries in our sample politicize ambassadors, although not in the US. The US almost exclusively selects political appointees when recruiting non-career ambassadors. The results highlight the importance of more comparative diplomatic studies, since countries politicize ambassador appointments to different degrees and by various methods.

Our study also contributes to public administration scholarship, which, despite its longstanding interest in the issue of politicization, habitually omits MFAs. We provide insights into this specific type of public agency, which, as our data show, diverges to some extent from the overall politicization patterns of public administration. Of particular interest to public administration scholars might be the observed inclination to appoint ‘politically connected professionals’ to postings of major political importance, implying that these appointments may be driven by a wish for greater political control. These findings illustrate how politicization plays into, and may be driven by, international relations.

Despite these contributions, our limited empirical sample does not allow for more sophisticated analyses. We thus hope that our study will inspire further research on the important topic of the politicization of diplomacy. For instance, it would be interesting to study the stability of our results across time and space, including more administrative traditions and a greater number of country contexts. Except Mexico, our cases are selected from the global North. How well our findings travel to other parts of the world remains to be explored. We therefore encourage scholars with expertise in other country contexts to address the question of politicization in diplomacy.

Moreover, our limited data did not allow for an exploration of the whole range of possible reasons for the political appointments of diplomats. For instance, in addition to control and patronage, appointing a politician to a diplomatic position might be a political punishment—eliminating individuals from the domestic political scene by sending them to far-off locations.86 In these cases, what we interpret as a reward may in practice be a ‘golden cage’. Such nuances require careful qualitative work in future research.

The kinds of diplomatic positions that are politicized pose another set of interesting questions. Ambassadorships constitute the pinnacle of the diplomatic career, and a politicization of these positions may weaken the esprit de corps and disincentivize competent people from pursuing such a career. Nevertheless, as long as there are enough professional diplomats assisting ambassadors in their tasks as heads of mission, these lower-rank embassy staff may be able to cover up embarrassing mistakes and compensate for a lack of professional skills in the ambassador. However, what if politicization reaches lower ranks of diplomats? How does that affect bilateral diplomatic relations? The fact that politicization does not always stop at the level of agency heads is well known in the public administration literature,87 and there are examples of states that have attempted to thoroughly politicize foreign services. For instance, in the making of the new diplomatic elite after the revolution of 1979, the Iranian regime replaced almost all career diplomats by loyal political supporters who acted as ‘apostles of the revolution’88 abroad. It soon became clear, though, that Iranian diplomats’ lack of professional skills and their refusal to adapt to international diplomatic norms endangered the stability of the state they served. This case testifies to the pivotal role of diplomats; their professionalism, skills and interactions constitute a significant part of international relations.

A fourth promising avenue for future research is gender patterns in the politicization of diplomacy. There are many ways in which gender and politicization may be interrelated, yet few of them have been explored. Several of the early American and Swedish female trailblazers in diplomacy were recruited from politics,89 indicating that the ‘glass ceilings’ of the MFAs could sometimes be cracked from the outside. The extent to which these politically appointed ambassadors shattered those ceilings and paved the way for female career diplomats—or just landed on top of the hierarchy in their own separate space—is not clear. A comparative study of Latin American states by Matthias Erlandsen et al.90 shows, however, that under specific conditions, politicians use their discretionary power to make appointments to decrease the gender gap in ambassadorial postings.91 Expanding on what these specific conditions might be and how they may differ between states and parties would bring valuable insights to scholarship on women's representation in diplomacy. We are only beginning to understand the politicization of diplomacy and its role in international relations.

Footnotes

Daniel Strauss, ‘Biden's political appointments for ambassador posts rile career diplomats’, Guardian, 31 July 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jul/31/biden-political-appointments-ambassador-posts. (Unless otherwise noted at point of citation, all URLs cited in this article were accessible on 16 May 2024.)

For example Maria Schottenius, ‘Avdankade politiker bör inte få åtråvärda poster som ambassadörer’ [Retired politicians should not get sought-after appointments as ambassadors], Dagens Nyheter, 21 Sept. 2021, https://www.dn.se/kultur/maria-schottenius-avdankade-politiker-bor-inte-fa-atravarda-poster-som-ambassadorer; P. Michael McKinley, ‘The politicization of the state department is almost complete’, The Atlantic, 23 Oct. 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/10/state-departments-politicization-almost-complete/616795.

For example Ryan M. Scoville, ‘Unqualified ambassadors’, Duke Law Journal 69: 1, 2019, pp. 71–195; Christian Lequesne, ‘Ministries of foreign affairs: a crucial institution revisited’, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 15: 1–2, 2020, pp. 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-BJA10003.

Matt Apuzzo and Benjamin Novak, ‘In Hungary, a freewheeling Trump ambassador undermines U.S. diplomats’, New York Times, 22 Oct. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/22/world/europe/david-cornstein-hungary-trump-orban.html.

Geoffrey Wiseman, ‘Expertise and politics in ministries of foreign affairs: the politician–diplomat nexus’, in Christian Lequesne, ed., Ministries of foreign affairs in the world: actors of state diplomacy (Boston, MA: Brill Online Books, 2022), pp. 119–49.

Christian Lequesne, ‘Populist governments and career diplomats in the EU: the challenge of political capture’, Comparative European Politics, vol. 19, 2021, pp. 779–95, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00261-6.

James E. Rauch and Peter B. Evans, ‘Bureaucratic structure and bureaucratic performance in less developed countries’, Journal of Public Economics 75: 1, 2000, pp. 49–71, http://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00044-4; David E. Lewis, The politics of presidential appointments: political control and bureaucratic performance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008); Bo Rothstein and Jan Teorell, ‘What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions’, Governance 21: 2, 2008, pp. 165–90, http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00391.x; Carl Dahlström, Victor Lapuente and Jan Teorell, ‘Public administration around the world’, in Sören Holmberg and Bo Rothstein, eds, Good government: the relevance of political science (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2012), pp. 40–67; Agnes Cornell and Victor Lapuente, ‘Meritocratic administration and democratic stability’, Democratization 21: 7, 2014, pp. 1286–304, https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.960205; Marina Nistotskaya and Luciana Cingolani, ‘Bureaucratic structure, regulatory quality, and entrepreneurship in a comparative perspective: cross-sectional and panel data evidence’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26: 3, 2016, pp. 519–34, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv026; Birgitta Niklasson, Peter Munk Christiansen and Patrik Öhberg, ‘Speaking truth to power: political advisers’ and civil servants’ responses to perceived harmful policy proposals’, Journal of Public Policy 40: 3, 2020, pp. 492–512, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000508.

See Sean Gailmard and John W. Patty, Learning while governing: expertise and accountability in the executive branch (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2013); Embassy Networking for Diplomats, ‘In general, do political appointees or career diplomats make the best ambassadors?’, https://embassymagazine.com/in-general-do-political-appointees-or-career-diplomats-make-the-best-ambassadors.

Patrick Porter, ‘Why America's grand strategy has not changed: power, habit, and the U.S. foreign policy establishment’, International Security 42: 4, 2018, pp. 9–46, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00311; Matt Malis, ‘Conflict, cooperation, and delegated diplomacy’, International Organization 75: 4, 2021, pp. 1018–57, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000102; Elizabeth N. Saunders, ‘Elites in the making and breaking of foreign policy’, Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 25, 2022, pp. 219–40, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-103330.

A smaller number of ambassadors might be placed in the capital of the sending state. These include ambassadors-at-large responsible for an issue area such as gender equality or the environment.

Brian Hocking, Foreign ministries: change and adaptation (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999); Brian Hocking, ‘Ministries of foreign affairs’, in Knud Erik Jorgensen et al., eds, The SAGE handbook of European foreign policy (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2015), pp. 331–43; Lequesne, Ministries of foreign affairs, pp. 15–38.

Andrew K. Rose, ‘The foreign service and foreign trade: embassies as export promotion’, World Economy 30: 1, 2007, pp. 22–38, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00870.x.

Brian M. Pollins, ‘Does trade still follow the flag?’, The American Political Science Review 83: 2, 1989, pp. 465–80, https://doi.org/10.2307/1962400; Peter A. G. van Bergeijk, Mina Yakop and Henri L. F. de Groot, ‘The economic effectiveness of diplomatic representation: an economic analysis of its contribution to bilateral trade’, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 6: 1–2, 2011, pp. 101–20, https://doi.org/10.1163/187119111X566751.

Benjamin E. Bagozzi and Steven T. Landis, ‘The stabilizing effects of international politics on bilateral trade flows’, Foreign Policy Analysis 11: 2, 2015, pp. 151–71, https://doi.org/10.1111/fpa.12034.

Christer Jönsson and Karin Aggestam, ‘Diplomacy and conflict resolution’, in Jacob Bercovitch, Victor Kremenyuk and I. William Zartman, eds, The SAGE handbook of conflict resolution (United Kingdom: SAGE, 2008), pp. 33–51.

Keith Hamilton and Richard Langhorne, The practice of diplomacy: its evolution, theory and administration (London: Routledge, 1995).

Rolando Stein, ‘Diplomatic training around the world’, in Kishan S. Rana and Jovan Kurbalija, eds, Foreign ministries: managing diplomatic networks and optimizing value (Malta and Geneva: DiploFoundation, 2007), pp. 235–64.

United Nations, Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961, adopted 18 April 1961; entered into force 24 April 1964, https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/9_1_1961.pdf.

Deepak Nair, ‘Sociability in international politics: golf and ASEAN's Cold War Diplomacy’, International Political Sociology 14: 2, 2020, pp. 196–214, http://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olz024; Birgitta Niklasson, ‘The gendered networking of diplomats’, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 15: 1–2, 2020, pp. 13–42, http://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-BJA10005; Katarzyna Jezierska, ‘Maternalism. Care and control in diplomatic engagements with civil society’, Review of International Studies, publ. online 22 March 2024, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000238.

Wiseman, ‘Expertise and politics’.

Merje Kuus, ‘Transnational bureaucracies: how do we know what they know?’, Progress in Human Geography 39: 4, 2015, pp. 432–48, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514535285; Jérémie Cornut, ‘Diplomacy, agency, and the logic of improvisation and virtuosity in practice’, European Journal of International Relations 24: 3, 2018, pp. 712–36, http://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117725156.

Lequesne, ‘Populist governments and career diplomats’.

Paul Sharp and Geoffrey Wiseman, ‘The diplomatic corps’, in Costas M. Constantinou, Pauline Kerr and Paul Sharp, eds, The SAGE handbook of diplomacy (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2016), pp. 171–84.

Lewis, The politics of presidential appointments; Evan T. Haglund, ‘Striped pants versus fat cats: ambassadorial performance of career diplomats and political appointees’, Presidential Studies Quarterly 45: 4, 2015, pp. 653–78, https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12223; Scoville, ‘Unqualified ambassadors’; Dennis C. Jett, American ambassadors: a guide for aspiring diplomats and foreign service officers (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022).

Haglund, ‘Striped pants versus fat cats’; Jett, American ambassadors.

Gary E. Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants of ambassadorial appointments’, Presidential Studies Quarterly 45: 3, 2015, pp. 445–66, https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12205; Eric Arias and Alastair Smith, ‘Tenure, promotion and performance: the career path of US ambassadors’, Review of International Organizations, vol. 13, 2018, pp. 77–103, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-017-9277-0; Johannes Fedderke and Dennis Jett, ‘What price the court of St. James? Political influences on ambassadorial postings of the United States of America’, Governance 30: 3, 2017, pp. 483–515, https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12254; Octavio Amorim Neto and Andrés Malamud, ‘The policy-making capacity of foreign ministries in presidential regimes: a study of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, 1946–2015’, Latin American Research Review 54: 4, 2019, pp. 812–34 at p. 818, https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.273.

Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’; George A. Krause and Anne Joseph O’Connell, ‘Experiential learning and presidential management of the U.S. federal bureaucracy: logic and evidence from agency leadership appointments’, American Journal of Political Science 60: 4, 2016, pp. 914–31, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12232; Fedderke and Jett, ‘What price the court of St. James?’.

David Lindsey, ‘Diplomacy through agents’, International Studies Quarterly 61: 3, 2017, pp. 544–56 at p. 545, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx037.

See Lewis, The politics of presidential appointments; Arias and Smith, ‘Tenure, promotion and performance’.

For example Haglund, ‘Striped pants versus fat cats’; Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’.

Stein, ‘Diplomatic training’.

Matthias Erlandsen, María Fernanda Hernández-Garza and Carsten-Andreas Schulz, ‘Madame President, Madame Ambassador? Women presidents and gender parity in Latin America's diplomatic services’, Political Research Quarterly 75: 2, 2022, pp. 425–440, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912921997922.

B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre, The politicization of the civil service in a comparative perspective: the quest for control (London and New York: Routledge, 2004); Luc Rouban, ‘Politicization of the civil service’, in B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre, eds, The SAGE handbook of public administration (London: SAGE, 2012), pp. 380–91; Tobias Bach and Kai Wegrich, ‘Politicians and bureaucrats in executive government’, in Rudy B. Andeweg et al., eds, The Oxford handbook of political executives (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 525–46.

Jørgen Gronnegaard Christensen, Robert Klemmensen and Niels Opstrup, ‘Politicization and the replacement of top civil servants in Denmark’, Governance 27: 2, 2014, pp. 215–41, https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12036; Thurid Hustedt and Heidi Houlberg Salomonsen, ‘Ensuring political responsiveness: politicization mechanisms in ministerial bureaucracies’, International Review of Administrative Sciences 80: 4, 2014, pp. 746–65, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314533449.

Christensen, Klemmensen and Opstrup, ‘Politicization and the replacement of top civil servants in Denmark’.

Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, ‘The politicization of regulatory agencies: between partisan influence and formal independence’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26: 3, 2016, pp. 507–18, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv022.

Carl Dahlström and Birgitta Niklasson, ‘The politics of politicization in Sweden’, Public Administration 91: 4, 2013, pp. 891–907, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02113.x; Petr Kopecký and Peter Mair, ‘Conclusion: party patronage in contemporary Europe’, in Petr Kopecký, Peter Mair and Maria Spirova, eds, Party patronage and party government in European democracies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 357–74; Petr Kopecký et al., ‘Party patronage in contemporary democracies: results from an expert survey in 22 countries from five regions’, European Journal of Political Research 55: 2, 2016, pp. 416–31, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12135. These two latter studies are rare examples of politicization scholarship that include the foreign service, although in a cursory fashion.

Renate Mayntz and Hans-Ulrich Derlien, ‘Party patronage and politicization of the West German administrative elite 1970–1987—toward hybridization?’, Governance 2: 4, 1989, pp. 384–404 at p. 401, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.1989.tb00099.x.

Rauch and Evans, ‘Bureaucratic structure’; Lewis, The politics of presidential appointments; Rothstein and Teorell, ‘What is quality of government?’; Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, ‘Public administration’.

Peters and Pierre, Politicization of the civil service; Christopher Hood and Martin Lodge, The politics of public service bargains: reward, competency, loyalty—and blame (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Christensen, Klemmensen and Opstrup, ‘Politicization and the replacement of top civil servants in Denmark’; Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, ‘Public administration’; Rouban, ‘Politicization of the civil service’, p. 381; Richard Shaw and Chris Eichbaum, ‘Ministers, minders and the core executive: why ministers appoint political advisers in Westminster contexts’, Parliamentary Affairs 67: 3, 2014, pp. 584–616, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gss080.

B. Guy Peters, Administrative traditions: understanding the roots of contemporary administrative behavior (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), pp. 23–5.

Peters and Pierre, The politicization of the civil service; Peters, Administrative traditions, p. 162; Christopher A. Cooper, ‘Politicization of the bureaucracy across and within administrative traditions’, International Journal of Public Administration 44: 7, 2021, pp. 564–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1739074.

Sandra Van Thiel, ‘Comparing agencies across countries’, in Koen Verhoest, Sandra Van Thiel, Geert Bouckaert and Per Lægreid, eds, Government agencies: public sector organizations (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 18–26.

Kopecký et al., ‘Party patronage in contemporary democracies’.

Joel D. Aberbach, Robert D. Putnam and Bert A. Rockman, Bureaucrats and politicians in western democracies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981); B. Guy Peters, Comparing public bureaucracies: problems of theory and method (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1988); Jon Pierre, Bureaucracy in the modern state: an introduction to comparative public administration (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1995).

Mayntz and Derlien, ‘Party patronage and politicization’; Peters and Pierre, The politicization of the civil service; Lewis, The politics of presidential appointments; Rouban, ‘Politicization of the civil service’.

Strauss, ‘Biden's political appointments’.

Elin Haugsgjerd Allern, ‘Appointments to public administration in Norway: no room for political parties?’, in Kopecký, Mair and Spirova, eds, Party patronage and party government in European democracies, pp. 272–93.

Carol Lancaster, Foreign aid: diplomacy, development, domestic politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Kopecký and Mair, ‘Conclusion’, p. 362.

Matthew Flinders, ‘Party patronage in the United Kingdom: a pendulum of public appointments’, in Kopecký, Mair and Spirova, eds, Party patronage and party government in European democracies, pp. 335–54 at p. 348. See also Peters and Pierre, The politicization of the civil service; Rouban, ‘Politicization of the civil service’; Jan-Hinrik Meyer-Sahling, ‘The institutionalization of political discretion in post-communist civil service systems: the case of Hungary’, Public Administration 84: 3, 2006, pp. 693–715, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00608.x.

Peters, Administrative traditions, p. 104.

Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, ‘Public administration’; Kopecký and Mair, ‘Conclusion’; Kopecký et al., ‘Party patronage in contemporary democracies’.

Terry M. Moe and Michael Caldwell, ‘The institutional foundations of democratic government: a comparison of presidential and parliamentary systems’, Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 150: 1, 1994, pp. 171–95.

Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, ‘Public administration’.

Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’; Arias and Smith, ‘Tenure, promotion and performance’; Fedderke and Jett, ‘What price the court of St. James?’.

Haglund, ‘Striped pants versus fat cats’; Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’.

Melvin Small and J. David Singer, ‘The diplomatic importance of states, 1816–1970: an extension and refinement of the indicator’, World Politics 25: 4, 1973, pp. 577–99, https://doi.org/10.2307/2009953.

Small and Singer, ‘The diplomatic importance’.

Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’, p. 462.

Small and Singer, ‘The diplomatic importance’; Rose, ‘The foreign service and foreign trade’.

See online appendix for rules of appointment: https://www.gu.se/en/gendip/gendip-publications.

Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, ‘Public administration’.

Moe and Caldwell, ‘The institutional foundations of democratic government’.

Philip Kelly, ‘Recent United States ambassadors to the Caribbean: an appraisal’, Caribbean Studies 17: 1/2, 1977, pp. 123–33; Stein, ‘Diplomatic training’; Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’.

Erlandsen, Hernández-Garza and Schulz, ‘Madame President, Madame Ambassador?’.

Birgitta Niklasson and Ann E. Towns, ‘Diplomatic gender patterns and symbolic status signaling: introducing the GenDip dataset on gender and diplomatic representation’, International Studies Quarterly 67: 4, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqad089.

We deal only with bilateral postings, i.e., embassies placed in a foreign capital. Multilateral postings—accreditations to international organizations—are omitted.

See online appendix: https://www.gu.se/en/gendip/gendip-publications.

See Costas M. Constantinou, Noé Cornago and Fiona McConnell, ‘Transprofessional diplomacy’, Brill Research Perspectives in Diplomacy and Foreign Policy 1: 4, 2016, pp. 1–66, https://doi.org/10.1163/24056006-12340005; Wiseman, ‘Expertise and politics’.

Small and Singer, ‘The diplomatic importance’.

Small and Singer, ‘The diplomatic importance’.

Wiseman, ‘Expertise and politics’.

Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, ‘Public administration’.

Haglund, ‘Striped pants versus fat cats’; Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’.

Peters, Administrative traditions.

Hollibaugh Jr, ‘The political determinants’.

To ensure that the US did not skew the results, we also performed calculations excluding US appointments. The overall result remained the same, but there was no longer a significant difference between political appointees and other groups.

This means that in a random sample, there is only a 0.1% risk that this difference is caused by chance. Our sample is not random, but we still use a t-test as an indication of which results are particularly interesting.

This means that in a random sample, there is only a 10% (∗) risk, or a 5% (**) risk that this difference is caused by chance. Our sample is not random, but we still use a t-test as an indication of which results are particularly interesting.

Pearson correlation=0.420 (significant at the 0.01 level). This means that a high level of hardship fairly often goes together with a high rank score (which means a low rank, since the highest ranked countries have the lowest rank score) and that there is only a 1% risk that this correlation is caused by chance. However, average rank has a significant effect on the appointment of non-career diplomats even when the level of hardship is controlled. See regression analyses in the online appendix: https://www.gu.se/en/gendip/gendip-publications.

This means that in a random sample, there is only a 0.8% risk that this pattern is caused by chance. Our sample is not random, but we still use a t-test as an indication of which results are particularly interesting.

Small and Singer, ‘The diplomatic importance’.

Lequesne, ‘Ministries of foreign affairs’; Birgitta Niklasson and Ann E. Towns, ‘Introduction: approaching gender and ministries of foreign affairs’, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 17: 3, 2022, pp. 339–69, https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191x-bja10123.

See Arias and Smith, ‘Tenure, promotion and performance’.

Jett, American ambassadors.

Carl Dahlström and Victor Lapuente, ‘Explaining cross-country differences in performance-related pay in the public sector’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20: 3, 2010, pp. 577–600, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mup021.

Guillaume Beaud, ‘The making of a diplomatic elite in a revolutionary state: loyalty, expertise and representativeness in Iran's Ministry of Foreign Affairs’, in Lequesne, ed., Ministries of foreign affairs, pp. 89–115 at p. 95.

Ann Miller Morin, Her Excellency: an oral history of American women ambassadors (New York: Twayne, 1995); Maj-Inger Klingvall and Gabriele Winai Ström, Från Myrdal till Lindh: svenska diplomatprofiler [From Myrdal to Lindh: Swedish diplomat profiles] (Möklinta: Gidlunds förlag, 2010); Sylvia Bashevkin, ‘The taking of Foggy Bottom? Representation in US diplomacy’, in Karin Aggestam and Ann E. Towns, eds, Gendering diplomacy and international negotiation (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2018), pp. 45–63, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58682-3_3; Philip Nash, Breaking protocol: America's first female ambassadors, 1933–1964 (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2020).

Erlandsen, Hernández-Garza and Schulz, ‘Madame President, Madame Ambassador?’.

See also Karla Gobo and Claudia Santos, ‘The social origin of career diplomats in Brazil's Ministry of Foreign Affairs: still an upper-class elite?’, in Lequesne, ed., Ministries of foreign affairs, pp. 15–38.

Author notes

We would like to thank the Swedish Research Council for financing the project ‘Gender and Diplomacy’, which rendered this article possible. We are also deeply grateful to the research assistants who have worked with the data collection: Ingrid Andreasson, Daria Badescu, Erik Brinde, Kajsa Evertsson, Nina Kovalicka and Mie Sorensen. Finally, many thanks to all the people who have provided comments and support: the reviewers, Kristin Eggeling, Ann-Marie Ekengren, Heidi Houlberg Salomonsen, Victor Lapuente, Marina Nistotskaya, Paulina Rivera Chávez, Jennifer Selin, Ann Towns and Joris van der Voet.