-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elina Rasp, Kristiina Rönö, Anna But, Mika Gissler, Päivi Härkki, Oskari Heikinheimo, Liisu Saavalainen, Burden of somatic morbidity associated with a surgically verified diagnosis of endometriosis at a young age: a register-based follow-up cohort study in Finland, Human Reproduction, Volume 40, Issue 4, April 2025, Pages 623–632, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaf032

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

How does the burden of somatic disorders compare between women with surgically verified endometriosis diagnosed in adolescence or early adulthood, and matched women without a history of endometriosis?

Women with endometriosis diagnosed at a young age had a higher incidence of several somatic disorders and a higher number of hospital visits compared to women without endometriosis.

Endometriosis is associated with an increased risk of several somatic disorders, including autoimmune, inflammatory, and pain-related disorders with higher utility of health care resources. There may be differences in the experience of pain relating to the subtypes of endometriosis. Depression and anxiety are linked to endometriosis and increase overall somatic comorbidity.

Longitudinal retrospective register-based cohort study utilizing episode data from specialized care; 2680 women under 25 years with a surgical of diagnosis endometriosis in 1998–2012, and 5338 reference women of the same age and municipality followed up from the index day to the end of 2019, emigration, death or the outcome of interest.

We analysed incidence rates, cumulative incidence rates, and crude hazard rate ratios (HR) with 95% CIs across 15 groups of somatic disorders. Subgroup analyses were conducted among women with endometriosis, by (i) type of endometriosis—ovarian only (n = 601) versus combined types (n = 2079), and (ii) pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety (n = 270) versus those without such diagnoses (n = 2410).

Women reached a median age of 38 (IQR 34–42) years after a median follow-up of almost 16 (12, 19) years. Compared to the reference cohort, women with endometriosis had a higher incidence of several somatic disorders during the follow-up. By the age of 40 years, 38% of women with endometriosis and 9% of the reference cohort had diagnoses of infertility (HR 5.88 [95% CI 5.24–6.61]). The corresponding figures for genital tract infections were 24% and 6% (4.64 [4.03–5.36]), symptoms and signs of pain 62% and 28% (3.27 [3.04–3.51]), migraine 15% and 6.4% (2.49 [2.13–2.92]), and chronic pain conditions 33% and 19% (2.01 [1.83–2.22]), respectively. In women with endometriosis, a higher incidence was seen also for dyspareunia, uterine myomas, celiac disease, asthma, anaemia, high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases; autoimmune diseases, and disorders of the thyroid gland. For women with ovarian endometriosis only, we observed a lower HR of high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases, asthma, migraine, and pain-related disorders compared to those with other or combined types of endometriosis. Within the endometriosis cohort, women with pre-existing diagnoses of depression or anxiety had higher HRs of several somatic disorders compared to those without such diagnoses. The number of hospital visits after the index day was higher in women with endometriosis when compared to the reference cohort (40 vs 18).

Confounding bias may arise from the reliance on registry-based hospital diagnoses, as women undergoing surgery are already engaged with health care, and, subsequently, more likely to receive new diagnoses. Furthermore, the homogenous population of Finland limits the generalizability of these findings.

Surgical diagnosis of endometriosis at a young age is associated with a burden of somatic disorders, emphasizing importance of comprehensive approach to management of endometriosis and endometriosis-related conditions. Further studies are needed to clarify the varying reasons behind these associations. However, the results of this study suggest that pain and mental health may play a key role in the development of subsequent somatic disorders. Therefore, careful management of primary dysmenorrhea and mental health in young women is essential.

Funding was received from the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa, and from Finska Läkaresällskapet. E.R. acknowledges financial support from The Finnish Society of Research for Obstetrics and Gynaecology and The Finnish Medical Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. O.H. serves occasionally on advisory boards for Bayer AG, Gedeon Richter, and Roche, has received travel support from Gedeon Richter, has received consulting fees from Orion Pharma and Nordic Pharma, and has helped to organize and lecture at educational events for Bayer AG and Gedeon Richter. The other authors report no conflict of interest concerning the present work.

N/A.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory estrogen-dependent disease affecting 6–10% of reproductive-aged women (Bulun et al., 2019; Rowlands et al., 2021). Common symptoms include pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility (Zondervan et al., 2020). Women with endometriosis face elevated risks of various somatic conditions (Kvaskoff et al., 2015; Teng et al., 2016; Rossi et al., 2023) including autoimmune (Sinaii et al., 2002; Eisenberg et al., 2012; Shigesi et al., 2019) inflammatory (Ferrero et al., 2005; Bungum et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2017), and pain-related disorders (Williams, 2018).

Different subtypes of endometriosis seem to impact pain experience differently (Nisolle and Donnez, 1997; Chapron et al., 2012). For example, women with isolated deep endometriosis often report experiencing more severe pain symptoms (Rocha et al., 2023), whereas those with isolated ovarian endometriomas typically report milder pain manifestations (Khan et al., 2013). Additionally, higher severity of pelvic pain in endometriosis patients correlates with poorer mental health (Facchin et al., 2017; Warzecha et al., 2020; Estes et al., 2021) and most mental illnesses heighten the risk of various subsequent medical conditions (Momen et al., 2020).

In the present follow-up study, we investigated the burden of somatic morbidity in women diagnosed with surgically verified endometriosis before the age of 25 years, by examining the incidence of somatic disorders and hospital care utilization in this group of patients in comparison with a matched reference cohort. Furthermore, we aimed to explore the effect of the subtype of endometriosis as well as a pre-existing diagnosis of depression and anxiety on the risk of subsequent somatic conditions. In our study, somatic disorders refer to a broad group of physical health conditions affecting various organ systems, distinct from mental health or psychological disorders.

Materials and methods

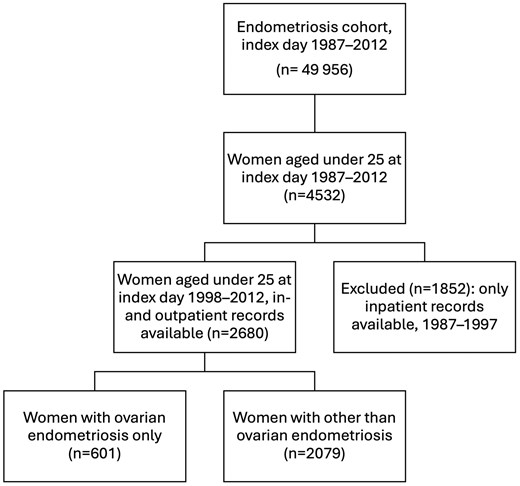

This study is part of a large nationwide cohort study of endometriosis. Women with the first surgically verified diagnosis of endometriosis (n = 49 956) between 1987 and 2012 in Finland were identified from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (FHDR). The FHDR contains all admissions to hospital-based inpatient departments since 1987 and outpatient facilities since 1998. The diagnostic system used was the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) from 1987 to 1995, and Tenth Revision (ICD-10) from 1996 onwards. The diagnoses of interest were obtained from the FHDR recorded with ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes.

The formation of the cohort has been described before (Saavalainen et al., 2018). The reference cohort (n = 98 824) was obtained from the Finnish Population Information System, consisting of women of the same age and municipality who were alive and had no surgical diagnosis of endometriosis by the end of 2012. The index day was the hospital discharge day following health care episode with the first valid diagnosis of endometriosis by the operating physician. Relevant emergency and elective procedures where endometriosis was the primary or secondary diagnosis were categorized as surgically verified endometriosis to define the exposed group.

For the present study, we included 2680 women receiving a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis in 1998–2012 before the age of 25 years (Fig. 1). The reference group consisted of 5338 age- and municipality-matched women. Women with an index year starting from 1998 were included, as from that year onwards, the data included both inpatient and outpatient hospital visits. To assess the burden of somatic disorders following surgically verified endometriosis, we relied on data from both inpatient and outpatient hospital visits and considered both primary and secondary diagnoses. Women with diagnoses of interest set before the index day were considered prevalent cases. Follow-up started on the index day and continued until emigration, death, 31 December 2019, or the first specific outcome diagnosis in question, whichever came first.

We further divided endometriosis into subtypes of peritoneal (i.e. superficial), ovarian, and deep, as well as other and unknown forms and combinations of endometriosis based on the FHDR codes (Supplementary Table S1). The division was chosen to reflect the less painful and more painful subtypes of endometriosis based both on clinical experience and studies (Nisolle and Donnez, 1997; Chapron et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2013; Rocha et al., 2023). To accomplish this, we used diagnostic codes to identify women with endometriosis coded as ovarian type only (no other type(s) coded) at the index procedure. We compared this group with other coded locations of endometriosis (including peritoneal [i.e. superficial] endometriosis, deep, other, and combinations of types [also including ovarian endometriosis]) (Supplementary Table S1).

Somatic ICD codes related to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium were excluded as outcomes, as these were beyond the scope of the present study. Baseline and follow-up of psychiatric disorders were assessed and reported earlier (Rasp et al., 2024).

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was somatic registered morbidity diagnosed or treated in Finnish hospitals after the index day, divided into subgroups of disorders according to prior literature (Sinaii et al., 2002; Ferrero et al., 2005; De Ziegler et al., 2010; Eisenberg et al., 2012; Bungum et al., 2014; Maclaran et al., 2014; Kvaskoff et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2017; Parazzini et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2017; Shigesi et al., 2019; Rossi et al., 2023). Categories were combined if observations among cases or controls were fewer than five, resulting in 15 subgroups of somatic disorders: infertility, dyspareunia, genital tract infections, symptoms and signs of pain, uterine myomas, celiac disease, migraine, chronic pain conditions (dorsalgia; pain in joint; pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers and toes; fibromyalgia; tension-type headache), asthma, anaemia; high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases (ischemic heart and cerebrovascular diseases, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, venous embolisms); autoimmune diseases, disorders of thyroid gland, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and obesity (Supplementary Table S1). In addition to the main ICD-10 diagnosis categories, we further investigated several unique somatic disorders. These were the most common diagnostic codes encountered in the endometriosis cohort.

Additionally, we examined the occurrence of somatic diagnoses in relative to the subtypes of endometriosis (ovarian only vs others). Furthermore, we assessed whether a pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety before the index day impacted the risk of subsequent somatic disorders in the endometriosis population.

The secondary outcome of the study was the number of hospital visits, as determined by the recorded dates of each visit. First, we investigated the overall number of hospital visits before and after the index day from 1987 to 2019. We calculated the overall number of hospital visits at the following intervals: 1 year before the index day, 1 year after the index day, 1 to <5 years after, 5 to <10 years after, and 10 to <15 years after. To further assess hospital care use not directly associated with endometriosis, we investigated the number of visits when excluding the ICD codes related to gynaecological and obstetrical diagnoses (Supplementary Table S1).

Statistical analyses

Distributions of categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as medians and first and third quartiles (Q1, Q3). Differences in categorical variables were analysed using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Distributions of continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test.

In outcome-specific analysis, women with pre-existing diagnoses of interest were excluded to calculate the incidence rate along with 95% CIs per 10 000 person-years, and cumulative incidence at 30 and 40 years of age. In addition, Cox regression analysis was performed to assess crude hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs when comparing hazard ratios between various groups. We assessed the assumption of proportional hazards (PHs) through tests and graphical examination of scaled Schoenfeld residuals. When violated, we applied the Cox regression model with time-dependent coefficients by dividing the follow-up period into intervals. Women with the outcome of interest assigned before the index day were excluded from the corresponding analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software version 4.3.1.

Sensitivity analyses

A sensitivity analysis was conducted on women without pre-existing diagnoses of depression or anxiety between those with and without endometriosis to determine if such conditions influenced the burden of somatic disorders. To further assess the potential impact of pain on somatic outcomes, we compared the endometriosis and reference cohorts when restricting analyses to women with hospital-based primary diagnoses of signs and symptoms of pain, recorded prior to the index date.

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa approved the study (238/13/03/03/2013). The registry-keeping authorities approved data retrieval and linkage: the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL/5393/14.06.00/2023) and Statistics Finland (TK/3123/07.03.00/2023).

Results

Before the index day, the women with endometriosis more often had somatic disorders, diagnosis of depression or anxiety, prior hospital visits, and they more often had lower socioeconomic status than the reference cohort. The median age of the endometriosis cohort was 22.9 (Q1, Q3; 21.2, 24.1) years. After a median follow-up of 15.7 (11.9, 19.0) years, the median age was 37.9 (34.3, 41.6) years (Table 1).

Index day and follow-up characteristics of the endometriosis cohort and the reference cohort.a

| Endometriosis cohort (n = 2680) . | Reference cohort (n = 5338) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index day characteristic | |||

| Age at index day, years Median (Q1, Q3) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.1) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.0) | Matching criteria |

| 12–14 | 6 (0.24) | 12 (0.22) | |

| 15–19 | 318 (11.9) | 644 (12.1) | |

| 20–24 | 2356 (87.9) | 4682 (87.7) | |

| Birth cohort, n (%) | Matching criteria | ||

| 1970–1979 | 981 (34.2) | 1943 (36.4) | |

| 1980–1989 | 1560 (58.2) | 3118 (58.4) | |

| 1990–1999 | 139 (5.19) | 277 (5.19) | |

| No diagnoses before the index dayb | 18 (0.67) | 1577 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| Somatic disorders prior to index day | |||

| Infertility | 335 (12.5) | 20 (0.38) | <0.001 |

| Dyspareunia | 62 (2.31) | 5 (0.09) | <0.001 |

| Genital tract infections | 365 (13.6) | 95 (1.78) | <0.001 |

| Symptoms and signs of painc | 1278 (47.7) | 613 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Uterine myomas | 19 (0.71) | 2 (0.04) | <0.001 |

| Celiac disease | 11 (0.41) | 10 (0.19) | 0.1 |

| Migraine | 81 (3.02) | 71 (1.33) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pain conditionsd | 238 (8.89) | 167 (3.13) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 162 (6.04) | 192 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Anaemia | 24 (0.9) | 23 (0.43) | 0.016 |

| Autoimmune diseasese | 57 (2.13) | 98 (1.84) | 0.42 |

| Disorders of thyroid gland | 18 (0.67) | 45 (0.84) | 0.5 |

| Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease | 19 (0.71) | 30 (0.56) | 0.5 |

| High blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases | 31 (1.16) | 29 (0.5) | 0.004 |

| Obesity | 8 (0.3) | 26 (0.49) | 0.3 |

| Diagnosis of depression or anxiety before the index day | 270 (10.1) | 285 (5.34) | |

| Any visits before the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 14.0 (7.0, 28.0) | 8.0 (3.0, 19.0) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays before the index dayb, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 4.0) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up characteristic | |||

| Age at the end of follow-up, years, median (Q1, Q3) | 38.0 (34.4, 41.7) | 37.9 (34.2, 41.6) | |

| Follow-up time years, median (Q1, Q3) | 15.7 (12.0, 19.1) | 15.7 (11.8, 19.0) | |

| Socioeconomic status by 2020f | <0.001 | ||

| Self-employed persons | 173 (6.46) | 311 (5.83) | |

| Upper-level employees | 494 (18.4) | 1237 (23.2) | |

| Lower-level employees | 1174 (43.8) | 2088 (39.1) | |

| Manual workers | 255 (9.51) | 545 (10.2) | |

| Students | 100 (3.73) | 179 (3.35) | |

| Pensioners | 94 (3.51) | 151 (2.83) | |

| Others | 306 (11.4) | 600 (11.2) | |

| Any visits after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 40 (21, 73) | 18 (9, 35) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (2, 6) | 2 (2, 4) | <0.001 |

| Endometriosis cohort (n = 2680) . | Reference cohort (n = 5338) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index day characteristic | |||

| Age at index day, years Median (Q1, Q3) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.1) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.0) | Matching criteria |

| 12–14 | 6 (0.24) | 12 (0.22) | |

| 15–19 | 318 (11.9) | 644 (12.1) | |

| 20–24 | 2356 (87.9) | 4682 (87.7) | |

| Birth cohort, n (%) | Matching criteria | ||

| 1970–1979 | 981 (34.2) | 1943 (36.4) | |

| 1980–1989 | 1560 (58.2) | 3118 (58.4) | |

| 1990–1999 | 139 (5.19) | 277 (5.19) | |

| No diagnoses before the index dayb | 18 (0.67) | 1577 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| Somatic disorders prior to index day | |||

| Infertility | 335 (12.5) | 20 (0.38) | <0.001 |

| Dyspareunia | 62 (2.31) | 5 (0.09) | <0.001 |

| Genital tract infections | 365 (13.6) | 95 (1.78) | <0.001 |

| Symptoms and signs of painc | 1278 (47.7) | 613 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Uterine myomas | 19 (0.71) | 2 (0.04) | <0.001 |

| Celiac disease | 11 (0.41) | 10 (0.19) | 0.1 |

| Migraine | 81 (3.02) | 71 (1.33) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pain conditionsd | 238 (8.89) | 167 (3.13) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 162 (6.04) | 192 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Anaemia | 24 (0.9) | 23 (0.43) | 0.016 |

| Autoimmune diseasese | 57 (2.13) | 98 (1.84) | 0.42 |

| Disorders of thyroid gland | 18 (0.67) | 45 (0.84) | 0.5 |

| Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease | 19 (0.71) | 30 (0.56) | 0.5 |

| High blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases | 31 (1.16) | 29 (0.5) | 0.004 |

| Obesity | 8 (0.3) | 26 (0.49) | 0.3 |

| Diagnosis of depression or anxiety before the index day | 270 (10.1) | 285 (5.34) | |

| Any visits before the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 14.0 (7.0, 28.0) | 8.0 (3.0, 19.0) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays before the index dayb, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 4.0) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up characteristic | |||

| Age at the end of follow-up, years, median (Q1, Q3) | 38.0 (34.4, 41.7) | 37.9 (34.2, 41.6) | |

| Follow-up time years, median (Q1, Q3) | 15.7 (12.0, 19.1) | 15.7 (11.8, 19.0) | |

| Socioeconomic status by 2020f | <0.001 | ||

| Self-employed persons | 173 (6.46) | 311 (5.83) | |

| Upper-level employees | 494 (18.4) | 1237 (23.2) | |

| Lower-level employees | 1174 (43.8) | 2088 (39.1) | |

| Manual workers | 255 (9.51) | 545 (10.2) | |

| Students | 100 (3.73) | 179 (3.35) | |

| Pensioners | 94 (3.51) | 151 (2.83) | |

| Others | 306 (11.4) | 600 (11.2) | |

| Any visits after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 40 (21, 73) | 18 (9, 35) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (2, 6) | 2 (2, 4) | <0.001 |

n, (%). Q1, Q3—first and third quartile.

Matched by age and residence at the day of diagnosis of surgically verified endometriosis.

When followed-up for any diagnosis (interventions excluded).

Abdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified.

Dorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache.

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis.

Cases missing n = 84, controls missing n = 227.

Index day and follow-up characteristics of the endometriosis cohort and the reference cohort.a

| Endometriosis cohort (n = 2680) . | Reference cohort (n = 5338) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index day characteristic | |||

| Age at index day, years Median (Q1, Q3) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.1) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.0) | Matching criteria |

| 12–14 | 6 (0.24) | 12 (0.22) | |

| 15–19 | 318 (11.9) | 644 (12.1) | |

| 20–24 | 2356 (87.9) | 4682 (87.7) | |

| Birth cohort, n (%) | Matching criteria | ||

| 1970–1979 | 981 (34.2) | 1943 (36.4) | |

| 1980–1989 | 1560 (58.2) | 3118 (58.4) | |

| 1990–1999 | 139 (5.19) | 277 (5.19) | |

| No diagnoses before the index dayb | 18 (0.67) | 1577 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| Somatic disorders prior to index day | |||

| Infertility | 335 (12.5) | 20 (0.38) | <0.001 |

| Dyspareunia | 62 (2.31) | 5 (0.09) | <0.001 |

| Genital tract infections | 365 (13.6) | 95 (1.78) | <0.001 |

| Symptoms and signs of painc | 1278 (47.7) | 613 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Uterine myomas | 19 (0.71) | 2 (0.04) | <0.001 |

| Celiac disease | 11 (0.41) | 10 (0.19) | 0.1 |

| Migraine | 81 (3.02) | 71 (1.33) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pain conditionsd | 238 (8.89) | 167 (3.13) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 162 (6.04) | 192 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Anaemia | 24 (0.9) | 23 (0.43) | 0.016 |

| Autoimmune diseasese | 57 (2.13) | 98 (1.84) | 0.42 |

| Disorders of thyroid gland | 18 (0.67) | 45 (0.84) | 0.5 |

| Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease | 19 (0.71) | 30 (0.56) | 0.5 |

| High blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases | 31 (1.16) | 29 (0.5) | 0.004 |

| Obesity | 8 (0.3) | 26 (0.49) | 0.3 |

| Diagnosis of depression or anxiety before the index day | 270 (10.1) | 285 (5.34) | |

| Any visits before the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 14.0 (7.0, 28.0) | 8.0 (3.0, 19.0) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays before the index dayb, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 4.0) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up characteristic | |||

| Age at the end of follow-up, years, median (Q1, Q3) | 38.0 (34.4, 41.7) | 37.9 (34.2, 41.6) | |

| Follow-up time years, median (Q1, Q3) | 15.7 (12.0, 19.1) | 15.7 (11.8, 19.0) | |

| Socioeconomic status by 2020f | <0.001 | ||

| Self-employed persons | 173 (6.46) | 311 (5.83) | |

| Upper-level employees | 494 (18.4) | 1237 (23.2) | |

| Lower-level employees | 1174 (43.8) | 2088 (39.1) | |

| Manual workers | 255 (9.51) | 545 (10.2) | |

| Students | 100 (3.73) | 179 (3.35) | |

| Pensioners | 94 (3.51) | 151 (2.83) | |

| Others | 306 (11.4) | 600 (11.2) | |

| Any visits after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 40 (21, 73) | 18 (9, 35) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (2, 6) | 2 (2, 4) | <0.001 |

| Endometriosis cohort (n = 2680) . | Reference cohort (n = 5338) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index day characteristic | |||

| Age at index day, years Median (Q1, Q3) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.1) | 22.9 (21.2, 24.0) | Matching criteria |

| 12–14 | 6 (0.24) | 12 (0.22) | |

| 15–19 | 318 (11.9) | 644 (12.1) | |

| 20–24 | 2356 (87.9) | 4682 (87.7) | |

| Birth cohort, n (%) | Matching criteria | ||

| 1970–1979 | 981 (34.2) | 1943 (36.4) | |

| 1980–1989 | 1560 (58.2) | 3118 (58.4) | |

| 1990–1999 | 139 (5.19) | 277 (5.19) | |

| No diagnoses before the index dayb | 18 (0.67) | 1577 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| Somatic disorders prior to index day | |||

| Infertility | 335 (12.5) | 20 (0.38) | <0.001 |

| Dyspareunia | 62 (2.31) | 5 (0.09) | <0.001 |

| Genital tract infections | 365 (13.6) | 95 (1.78) | <0.001 |

| Symptoms and signs of painc | 1278 (47.7) | 613 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Uterine myomas | 19 (0.71) | 2 (0.04) | <0.001 |

| Celiac disease | 11 (0.41) | 10 (0.19) | 0.1 |

| Migraine | 81 (3.02) | 71 (1.33) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pain conditionsd | 238 (8.89) | 167 (3.13) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 162 (6.04) | 192 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Anaemia | 24 (0.9) | 23 (0.43) | 0.016 |

| Autoimmune diseasese | 57 (2.13) | 98 (1.84) | 0.42 |

| Disorders of thyroid gland | 18 (0.67) | 45 (0.84) | 0.5 |

| Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease | 19 (0.71) | 30 (0.56) | 0.5 |

| High blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases | 31 (1.16) | 29 (0.5) | 0.004 |

| Obesity | 8 (0.3) | 26 (0.49) | 0.3 |

| Diagnosis of depression or anxiety before the index day | 270 (10.1) | 285 (5.34) | |

| Any visits before the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 14.0 (7.0, 28.0) | 8.0 (3.0, 19.0) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays before the index dayb, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 4.0) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up characteristic | |||

| Age at the end of follow-up, years, median (Q1, Q3) | 38.0 (34.4, 41.7) | 37.9 (34.2, 41.6) | |

| Follow-up time years, median (Q1, Q3) | 15.7 (12.0, 19.1) | 15.7 (11.8, 19.0) | |

| Socioeconomic status by 2020f | <0.001 | ||

| Self-employed persons | 173 (6.46) | 311 (5.83) | |

| Upper-level employees | 494 (18.4) | 1237 (23.2) | |

| Lower-level employees | 1174 (43.8) | 2088 (39.1) | |

| Manual workers | 255 (9.51) | 545 (10.2) | |

| Students | 100 (3.73) | 179 (3.35) | |

| Pensioners | 94 (3.51) | 151 (2.83) | |

| Others | 306 (11.4) | 600 (11.2) | |

| Any visits after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 40 (21, 73) | 18 (9, 35) | <0.001 |

| Any overnight hospital stays after the index day2, median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (2, 6) | 2 (2, 4) | <0.001 |

n, (%). Q1, Q3—first and third quartile.

Matched by age and residence at the day of diagnosis of surgically verified endometriosis.

When followed-up for any diagnosis (interventions excluded).

Abdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified.

Dorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache.

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis.

Cases missing n = 84, controls missing n = 227.

Somatic disorders

After excluding women with pre-existing diagnoses of interest, we found associations between endometriosis and several somatic disorders. By the age of 40, 38% of women with endometriosis had been diagnosed with infertility, compared to 9% in the reference cohort. Similarly, the cumulative incidence rates were 24% versus 6% for genital tract infections, 62% versus 28% for symptoms and signs of pain, 14% versus 6.4% for migraine, and 33% versus 19% for chronic pain conditions. A higher incidence was seen also for later dyspareunia, uterine myomas, celiac disease, asthma, anaemia; high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases; autoimmune diseases, and disorders of the thyroid gland (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S2). The endometriosis cohort showed higher hazards across all the main ICD-10 categories (Supplementary Table S3), with further details on specific diagnoses provided in Supplementary Table S4.

![Incidence rate and hazard rate ratio of somatic disorders based on both main and secondary diagnoses following the index day, in women with surgically diagnosed endometriosis (n = 2680) before the age of 25 years as compared to the reference cohort (n = 5338). The women with specific somatic disorders before index day were excluded from disorder-specific analysis. PY, person-years. aImmune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis. bDorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache. cAbdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified. dProportional hazard assumption is violated.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/humrep/40/4/10.1093_humrep_deaf032/1/m_deaf032f2.jpeg?Expires=1750216812&Signature=3JBD1XY6nPhQnrJOdxaoOzCQ0yzyCW~SFKDim7HmZ79HJYtitR0cQT2-F6qSLNiMW67opGllQqndv9HP-HVdz5yHR-GxcPxpvXEnHIC6KDYtwISkVvBXYOJ8ipufY-HpmKJLDx6MCjlumRYssqbAj~IzgGGRbOeAhudxMgrTccxvitXSOISjMDEU~pDs3dsG0XB2rad3vp6DiYR8HI7yNe7ed8LsN8-yg8GRAdsODP1wC~rrkDqCcrnFziM5EMIsgyBFcgRneCagOE6kmqXD-prmUeiRzYn1Z4KiJZ0RCfD25nOa6KhIfCFxjF0Cka-lTdwvEst0-NREEZ-8SnmGmw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Incidence rate and hazard rate ratio of somatic disorders based on both main and secondary diagnoses following the index day, in women with surgically diagnosed endometriosis (n = 2680) before the age of 25 years as compared to the reference cohort (n = 5338). The women with specific somatic disorders before index day were excluded from disorder-specific analysis. PY, person-years. aImmune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis. bDorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache. cAbdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified. dProportional hazard assumption is violated.

For several somatic outcomes, the initial relative hazard difference between women with and without endometriosis decreased over time (non-PHs), however, the differences remained statistically significant. HR for infertility decreased from 16.3 (12.8, 20.8) for the first 3 years to 4.30 (3.53, 5.22) between 3 and 8 years, and further to 2.53 (2.03, 3.15) after 8 years. Similarly, for genital tract infections, the HR decreased from 6.43 (5.18, 7.98) in the first 6 years to 3.84 (3.09, 4.77) between 6 and 15 years, and further to 2.13 (1.34–3.38) after 15 years. For symptoms and signs of pain, the HR was 5.73 (5.03, 6.54) in the first 3 years, 2.60 (2.34, 2.89) between 3 and 12 years, and 1.83 (1.50, 2.32) beyond 12 years. The HR for chronic pain conditions remained higher for the first 15 years of follow-up, with an HR of 2.09 (1.89, 2.32) compared to 1.55 (1.18, 2.03) after 15 years.

Subtypes of endometriosis, pre-existing diagnoses of depression and anxiety

Additionally, for women with ovarian endometriosis only, a lower hazard of high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases; asthma, migraine, chronic pain conditions, and symptoms and signs of pain were seen compared to those with other or combined subtypes of endometriosis (Fig. 3).

![Incidence rate and hazard ratio of somatic disorders following the index day in women diagnosed with ovarian endometriosis (n = 601) as compared to women with other types of endometriosis (n = 2079) aged under 25 years at the index day. The women with specific somatic disorders before index day were excluded. PY, person-years. aDorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache. bAbdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified. cImmune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/humrep/40/4/10.1093_humrep_deaf032/1/m_deaf032f3.jpeg?Expires=1750216812&Signature=nnn-ao9sNvAHAgTzQVNkXLOwZtbFlJGkGeOSu15Bvm~IsfdaaP9DsFnqwQHHhOHjXTK2rEZEejYK12nQbOmYqtvATJv2pQTGOh00GSTsjgWh7xINQO2k3Lhwggz35sEhh7qC7Xkk3pGDy50Yp7ux9BwS4kvlmJlyRrXB3naDRIam6AG6NmxgxbV5nQ1axpx39k4TNzWrSdzbtfX~iF9sOR2yorfhcKKhM9Uqy3NAZsJCbaEULkIAc5in8NEyGH~01TuVJ3QxjcIR98VnlocKIi4sS88IPUm9j7hDwSpdTXUe8KH-WA4UQTxTVPptetJlSkcmA~WTmG3~Mj28iOG3OA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Incidence rate and hazard ratio of somatic disorders following the index day in women diagnosed with ovarian endometriosis (n = 601) as compared to women with other types of endometriosis (n = 2079) aged under 25 years at the index day. The women with specific somatic disorders before index day were excluded. PY, person-years. aDorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache. bAbdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified. cImmune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis.

Furthermore, of the women with endometriosis, 270 (10.1%) had received a primary diagnosis of depression or anxiety before the index day 1987–2012 (Table 1). A higher hazard of several somatic disorders was seen for women with endometriosis and a pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety compared to women with endometriosis but without such diagnoses (Fig. 4).

![Incidence rate and hazard ratio of somatic disorders following the index day in women with pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety (n = 270) as compared to women with no such diagnosis (n = 2410) before the surgical diagnosis of endometriosis under the age of 25 years. The women with specific somatic disorders before index day were excluded. PY, person-years. aImmune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis. bDorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache. cAbdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/humrep/40/4/10.1093_humrep_deaf032/1/m_deaf032f4.jpeg?Expires=1750216812&Signature=zujYOH0WYtkNV8G-vBNNLg-AyzszTCdtBQWzM1Y1He~9IYcDahFbqCAN2b4nOAsybXfc5UeS623cBVzWvqkbzZ5amOoF4noIGNn~U-dVbAIqY3btFM-~WhR1-z89e7cHY0~jP~CX1laAFgzx6oX2Gjn~1YmV6EraDUFmpJHlL7OXLS~x29H6nYQcMX28YomF8~AKbEF1gZMYhttGMUCsEN13oRAd7kOd-5oYKgI7Ho3TmLjhHP7N7TwuXRyf-pfrxWCC2f4wymOajD5OHgw8Ut~jyQexOF5x72hH450F4oYcWnBAD0yILBU4snBTphe3ixFUbomaq9RaiWx8VH3-WA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Incidence rate and hazard ratio of somatic disorders following the index day in women with pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety (n = 270) as compared to women with no such diagnosis (n = 2410) before the surgical diagnosis of endometriosis under the age of 25 years. The women with specific somatic disorders before index day were excluded. PY, person-years. aImmune thrombocytopenic purpura; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Primary adrenocortical insufficiency; Multiple sclerosis; Guillain–Barre syndrome; Iridocyclitis; Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified; Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pemphigus; Pemphigoid; Psoriasis; Alopecia areata; Vitiligo; Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor; Other rheumatoid arthritis; Juvenile arthritis; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Dermatopolymyositis; Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica; Polymyalgia rheumatica; Myasthenia gravis; Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma]; Systemic lupus erythematosus; Other forms of systemic lupus erythematosus; Systemic lupus erythematosus, unspecified; Sjögren syndrome; Ankylosing spondylitis. bDorsalgia; Pain in joint; Pain in limb, hand, foot, fingers, and toes; Fibromyalgia; Tension-type headache. cAbdominal and pelvic pain; Dysuria; Headache; Pain, unspecified.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding women with pre-existing diagnoses of depression or anxiety before the index day to assess whether the associations pointed by the main analyses were influenced by the pre-existing imbalance in these conditions. The results remained consistent (Supplementary Table S5).

By limiting the analysis to women with endometriosis and pre-existing pain diagnoses, as well as women in the reference cohort with similar pain diagnoses, we found that women with endometriosis had a higher risk of developing pain-related conditions, infertility, genital tract infections, and dyspareunia (Supplementary Fig. S1).

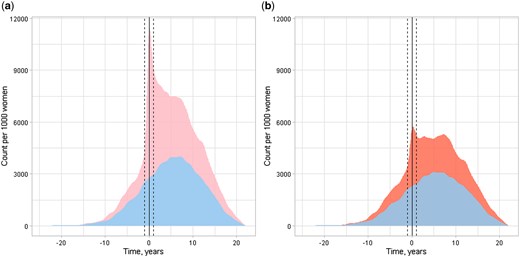

Hospital visits

As the secondary outcome, women with endometriosis had more hospital visits, both in- and outpatient, during the 10 years before and after the index day, as well as throughout the entire follow-up period. This difference persisted even after excluding visits with gynaecological and obstetrical diagnoses (Table 1, Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S6, Supplementary Fig. S2).

In- and outpatient hospital visits per 1000 women before and after the first surgical diagnosis of endometriosis (index day) of women aged under 25 years between 1998 and 2012. Endometriosis cohort (pink and red) consisting of 2680 women at the index day, and control (blue) consisting of 5338 age- and municipality-matched women at the index day. Solid vertical line at index date. Dashed vertical line at 1 year prior and after the index day. Count of the visits per 1000 women on y-axis, follow-up time on x-axis. (a) Any visits per 1000 women, (b) Any visits with gynaecological and obstetrical visits excluded per 1000 women

Discussion

Women receiving a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis as an adolescent or young adult exhibited a higher burden of several somatic disorders compared to the age- and municipality-matched reference cohort of women without endometriosis. Women with other or combined subtypes of endometriosis suffered more from several pain-related disorders compared to those with ovarian-only endometriosis. Among women with endometriosis, those with pre-existing diagnoses of depression or anxiety suffered more from various somatic disorders compared to those without such diagnoses. Moreover, increased hospital care utilization occurred both before and after the index day compared to those without endometriosis.

Relation to other studies

The link between endometriosis and overall morbidity has been investigated in various studies (Kvaskoff et al., 2015; Teng et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2017; Parazzini et al., 2017; Rossi et al., 2023). A Finnish population-based study of 349 women with endometriosis from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 found that women with endometriosis were twice as likely to have hospital-based diagnoses of non-gynaecological diseases compared to those without endometriosis (adjusted odds ratio 2.32; 95% CI, 1.07–5.02). Endometriosis was associated with allergies, infectious diseases, pain-related conditions, and respiratory diseases (Rossi et al., 2023). Other studies reported higher risks of several autoimmune diseases, allergic manifestations, asthma, ovarian, breast, and endometrial cancers, gastrointestinal diseases, migraine, anaemia, cardiovascular, and atopic diseases among endometriosis patients (Sinaii et al., 2002; Ferrero et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 2012; Bungum et al., 2014; Kvaskoff et al., 2015; Teng et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2017; Parazzini et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2017; Shigesi et al., 2019). Among gynaecological conditions, myomas (Maclaran et al., 2014), infertility (De Ziegler et al., 2010), and genital tract infections (Lin et al., 2016) were associated with endometriosis. None of the mentioned studies focused exclusively on diagnoses made at a young age or followed participants for as long as our study did. However, two of the studies stratified women into age groups (Sinaii et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2016). Notably, women who experienced pelvic symptoms at a younger age were reported to be more likely to develop conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, or chronic fatigue syndrome (Sinaii et al., 2002).

Our results indicate that, compared to the reference group, the largest relative differences were observed infertility, genital tract infections, symptoms and signs of pain, migraine, and for chronic pain conditions, with hazard ratios (HRs) ranging from 2 to 5 and much higher cumulative incidences in the endometriosis group, particularly as women aged. The narrow CIs observed for pain-related conditions likely reflect the high prevalence of these conditions in the endometriosis cohort. In contrast, dyspareunia, uterine myomas, celiac disease, asthma, anaemia, cardiovascular outcomes, autoimmune diseases, and disorders of the thyroid gland showed milder relative differences and smaller variations in cumulative incidence between endometriosis and reference cohorts. Compared to the reference cohort, time-dependent analyses showed higher hazards of infertility, genital tract infections, and pain-related conditions in the endometriosis cohort for the first years following the index day. This might, however, be explained by selection bias or reverse causation related to surgical management and diagnosis of endometriosis. Additionally, all the groups of ICD-10 codes were more prevalent among women with endometriosis.

Women with endometriosis generally exhibit increased regional hyperalgesia, allodynia, altered musculoskeletal pain response, and heightened pain sensitivity (Aredo et al., 2017; Vuontisjärvi et al., 2018). Ovarian hormones may influence musculoskeletal pain, migraine, temporomandibular disorder, and chronic pelvic pain (Hassan et al., 2014). Genetic correlations between endometriosis and other pain-related disorders have also been reported (Rahmioglu et al., 2023).

Different subtypes of endometriosis seem to impact pain experiences differently (Nisolle and Donnez, 1997; Chapron et al., 2012). Deep endometriosis is associated with more severe pain symptoms (Rocha et al., 2023), while ovarian endometriosis is linked to milder pain manifestations (Khan et al., 2013). Chronic pain conditions often co-occur with others (Williams, 2018). Our findings further support the hypothesis that ovarian endometriosis may have a distinct clinical presentation compared to other forms of the disease. The incidence of symptoms and signs of pain, chronic pain conditions, and migraine was lower in women with ovarian endometriosis compared to other forms of endometriosis. Interestingly, asthma and high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular diseases were also less prevalent among those with ovarian endometriosis. A Finnish population-based study on endometriosis and overall morbidity found no difference in the prevalence of non-gynaecological diagnoses within the main ICD-10 categories between different endometriosis subtypes (Rossi et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the researchers did not explore the impact of endometriosis subtypes on other groups of somatic diseases. In contrast, a French case–control study on migraine and endometriosis found a higher risk of ovarian and deep infiltrating endometriosis in women with migraine (Maitrot-Mantelet et al., 2020). However, the sample sizes of subtypes of endometriosis were limited compared to our study. We speculate that the complexity of chronic pain associated with endometriosis may contribute to various comorbid disorders and potentially introduce bias in studies, highlighting the need for more differentiated diagnostics and treatments. We aimed to further investigate the effect of pre-existing pain symptoms on the incidence of somatic disorders. In women with endometriosis and a pre-existing hospital diagnosis of pain symptoms, as well as in the reference cohort with similar diagnoses of prior pain, the endometriosis group showed stronger associations with infertility, genital tract infections, and pain-related conditions. These findings align with the results from the main analyses and emphasize consistency of these associations.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the impact of a pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety on overall morbidity in individuals with endometriosis. Endometriosis is associated with an increased risk of depression and anxiety, also among adolescent patients (Gao et al., 2020; Rasp et al., 2024). Those with more severe pain associated with endometriosis tend to experience poorer mental health (Facchin et al., 2017; Warzecha et al., 2020; Estes et al., 2021). Meanwhile, most mental health disorders heighten the risk of subsequent medical conditions (Momen et al., 2020). Our findings align with these observations. When accompanied by a pre-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety, endometriosis diagnosed at a young age was associated with an increased risk of various somatic conditions. The strongest associations were observed for pain-related conditions. HRs greater than two, though accompanied by broader CIs were found for anaemia, thyroid disorders, cardiovascular conditions, and obesity. These findings suggest that the combination of endometriosis and depression or anxiety may heighten the risk for both pain-related and metabolic conditions. Consistent with our results, a Swedish population-based cohort study reported that depression at a young age was associated with various somatic disorders, including autoimmune, infectious, endocrine, metabolic, nervous system, and circulatory system (Leone et al., 2021).

Several studies highlight the increased healthcare utilization by women diagnosed with endometriosis (Fuldeore et al., 2015; Soliman et al., 2019; Grundstrom et al., 2020; Eisenberg et al., 2022; Melgaard et al., 2023). Younger women under 25 or 30 years diagnosed with endometriosis show increased healthcare utilization compared to older women with endometriosis (Grundstrom et al., 2020; Eisenberg et al., 2022). Additionally, women with endometriosis experience a greater number of comorbidities at the time of their endometriosis diagnosis (Fuldeore et al., 2015; Soliman et al., 2019; Eisenberg et al., 2022).

In a US case-control study of 37 570 pairs, the overall use of outpatient care for endometriosis patients increased over a 5-year pre- and post-index period, with elevated inpatient care persisting for 1-year pre-diagnosis and 4-year post-diagnosis (Fuldeore et al., 2015). Another US-based retrospective cohort study of 15 615 women with endometriosis revealed heightened pre- and post-index healthcare utilization between women with and without endometriosis, with hospital admissions at 11.7% versus 7.1% and 33.1% versus 7.2%, respectively (Soliman et al., 2019). A Danish registry-based cohort study of 21 616 women with endometriosis showed increased primary and secondary healthcare use 10 years before the index day, with cases having 28% more inpatient contacts and 45% more outpatient contacts per year (Melgaard et al., 2023). Our findings align with these studies, indicating elevated hospital care utilization before and after the index day for both in- and outpatient care. Hospital care utilization increased both before and after the diagnosis of endometriosis, with elevated visit rates seen as early as 10 years prior to diagnosis. Interestingly, this pattern persisted even when gynaecological and obstetrical visits were excluded. The endometriosis cohort showed higher hazards across all the main ICD-10 categories, suggesting that women with endometriosis may have broader healthcare needs or a lower threshold for seeking care across various conditions as also suggested by Melgaard et al. (2023). This likely reflects not only the direct burden of the disease but also the ongoing management and monitoring of comorbid conditions associated with endometriosis.

Clinical relevance

While previous research has mainly focused on women diagnosed with endometriosis at any age, we focused on those diagnosed at a young age, further confirming the previous results. Both healthcare authorities and the women themselves should be informed about these comorbidities and consider counselling and assessing the symptoms, in order of prevention and treatment. Particular attention should be given to managing pain and the psychiatric disorders often associated with it, such as depression and anxiety, even appearing at a young age. The heightened healthcare utilization appears to be attributed not only to endometriosis-related visits but also by a rise in overall somatic comorbidity.

Research implications

Future studies are needed to explain the reasons for the association between endometriosis and somatic disorders. For example, the studies should include a comprehensive history of the comorbidities for both the endometriosis and reference groups, assess the role of the experienced pain and the impact of possible additional therapies for endometriosis and genetic factors. Moreover, comorbidity in women with endometriosis should be studied in comparison to women with other similar chronic conditions.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include a longitudinal study design, a long follow-up with diagnoses made during adolescence and early adulthood, a large sample size, utilization of registers with high-quality data (Sund, 2012) and a broad approach to different groups of somatic disorders. We were also able to compare the somatic outcomes between patients with ovarian-only endometriosis and those with other endometriosis subtypes and those with endometriosis and pre-existing diagnoses of depression or anxiety.

Our study also has limitations. First, our data are based on hospital records, so the results are most applicable to the corresponding populations and settings. Therefore, milder somatic disorders treated in primary care and patients not seeking treatment are not included. Conversely, individuals receiving hospital-based treatment for endometriosis often referred due to pain may undergo more thorough examinations, increasing the chance of being diagnosed with somatic disorders. Moreover, in Finland, for example, asthma, celiac disease, and migraine are managed mainly by general practitioners outside the hospitals. Therefore, the control group (or those with fewer visits) might not present a realistic picture of all the comorbidities treated outside hospitals. In addition, those receiving surgery for endometriosis under the age of 25 years might suffer from more severe or painful forms of the disease. As detailed in the Material and Methods, reference women were selected not to have a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis by the end of 2012. Only six (0.1%) reference women received a non-surgical diagnosis during the follow-up. Thus, the potential for misclassification and its impact on the study outcomes are minimal and unlikely to be significant.

We used registry-based data, which lacked information on some potential confounding factors such as pain experience, ethnicity, and lifestyle factors. To mitigate this, we matched participants by age and baseline municipality. Although we used high-quality register data, the retrospective design of our study limits our capacity to control unmeasured confounders, and we relied solely on pre-existing, predefined data. Additionally, the frequency of certain somatic disorders was decreased before the index day possibly due to the young age of participants. It is possible that women exhibiting symptoms of endometriosis may have been misdiagnosed with conditions such as genital tract infections. The subtypes of endometriosis were based on codes assigned at the index day surgery, and we cannot ascertain whether patients developed other types of endometriosis during the follow-up period. There is a risk of misclassification when comparing ovarian-only cases with other types, as the diagnosis is surgical. Additionally, we could not further distinguish between subtypes due to sample size constraints. Furthermore, deep infiltrating endometriosis was defined more accurately in the beginning of the 1990s. Furthermore, our results were robust in a sensitivity analysis conducted on women without pre-existing diagnoses of depression or anxiety, indicating that the differences were not solely due to pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Further, we cannot assert whether the control population suffered from pelvic pain or received a non-surgical diagnosis of endometriosis during the follow-up, or not. Since our data included no outpatient records before 1998, some of the diagnoses preceding the index day are only based on inpatient records. The population of Finland is relatively homogenous, which limits the generalizability of the findings globally. Additionally, variations exist among countries in how patients seek and receive specialized care for endometriosis and other conditions.

Conclusions

We find that an early diagnosis of endometriosis is related to increased overall morbidity due to several somatic disorders and increased use of hospital care. More pain-related disorders are associated with more painful subtypes of endometriosis. Co-existing diagnosis of depression or anxiety further increases the risk of several diagnoses of somatic disorders. A comprehensive treatment of endometriosis and other disorders, as well as effective pain management, could decrease overall healthcare utilization and improve patient-centred care.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to data protection and privacy legislation. The data sources are national register records which were made available specifically for this study and cannot be shared with third parties. Permission for similar data can be applied from the Finnish Social and Health Data Permit Authority Findata https://findata.fi/en/.

Authors’ roles

E.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. K.R.: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. A.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. M.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing. P.H.: Conceptualization, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. O.H.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. L.S.: Conceptualization, Validation, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Funding

Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa; Finska Läkaresällskapet; The Finnish Society of Research for Obstetrics and Gynaecology (E.R.); The Finnish Medical Foundation (E.R.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

O.H. serves occasionally on advisory boards for Bayer AG, Gedeon Richter, and Roche, has received travel support from Gedeon Richter, has received consulting fees from Orion Pharma and Nordic Pharma, and has helped to organize and lecture at educational events for Bayer AG and Gedeon Richter. The other authors report no conflict of interest concerning the present work.